Abstract

Quarantine conditions arising as a result of the coronavirus (COVID-19) have had a significant impact on global production-rates and supply chains. This has coincided with increased demands for medical and personal protective equipment such as face shields. Shortages have been particularly prevalent in western countries which typically rely upon global supply chains to obtain these types of device from low-cost economies. National calls for the repurposing of domestic mass-production facilities have the potential to meet medical requirements in coming weeks, however the immediate demand associated with the virus has led to the mobilisation of a diverse distributed workforce. Selection of appropriate manufacturing processes and underused supply chains is paramount to the success of these operations. A simplified medical face shield design is presented which repurposes an assortment of existing alternative supply chains. The device is easy to produce with minimal equipment and training. It is hoped that the methodology and approach presented is of use to the wider community at this critical time.

Keywords: COVID-19, Distributed manufacturing, Repurposed manufacture, Micro-supply chains, Medical face shields, Simplified design

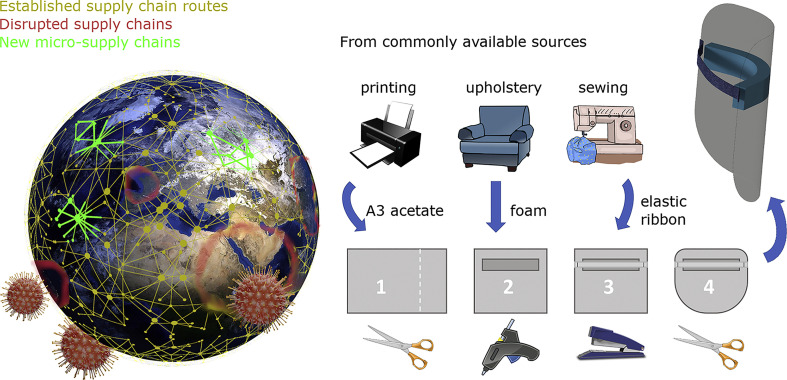

Graphical abstract

In recent decades, western countries have focused on manufacturing low-volume, high-value, high-margin products. Consequently, the production of high-volume, low-margin products has shifted towards low-cost economies, and long and sophisticated supply chains have been established. The application of just-in-time strategies and lean ideologies throughout these networks has led to significant cost reductions. However, these networks have poor resilience to global disruptions, with nearly 35% of manufacturers reporting disturbances due to the global coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic [1].

One such low-margin mass-produced item is face shields (medical visors) used as Personal Protection Equipment (PPE). The global spread of the virus has required governments to take harsh measures in imposing quarantines, with the knock-on-effect of halting manufacturing and exports [2,3]. These events, in combination with a surging demand created a shortage of PPE that has led to a global competition for sourcing materials and sanctions on exports [4]. One such approach is the European Commission's initiative on the joint procurement of PPE [5].

Across the world, national calls to produce ventilators, PPE and other urgently required medical equipment have been publicised [6], with significant numbers of mass production facilities being repurposed to meet this demand. These approaches will address the long term, high-production rates required, however take weeks-to-months to establish. Given that the critical time scale associated with the COVID-19 pandemic is on the order of days-to-weeks, the necessity of localised, cost-effective and rapid production has emerged.

Thus far, existing networks between medical institutions, research facilities and independent designers have been used to mobilise a diverse workforce. This has included developing the technology required to use a single ventilator for two patients, as well as repurposing scuba diving equipment for PPE [7]. The success of such “new products” relies not only on design and materials but also on ease of production and availability of manufacturing facilities and raw materials. Organically, this has led to the generation of new supply chains and distributed manufacturing systems.

Medical face shields have a significant potential for distributed manufacture using alternative materials. They are single-use head mounted devices worn as a physical barrier by medical personnel during aerosol generating procedures such as intubation, respiratory physiotherapy or oropharyngeal suction. These procedures are typically required in the treatment of patients experiencing acute respiratory distress. Given the expected increase in COVID-19 cases and global competition for sourcing PPE, many medical facilities currently do not have enough stock and/or reliable resources to meet the anticipated demand.

Face shields consist of a clear thermoformed polymer sheet held in place with an elasticated strap or a polymer frame manufactured by injection moulding which can be emulated at a local level through Additive Manufacturing (AM) [8]. However, AM is a slow process not suitable for mass production that requires skilled operators and relatively costly materials and equipment. Other researchers have designed systems that rely on sophisticated production techniques or bulk resources which are used by mass production PPE facilities, adding further pressure to stretched supply chains [9].

The novelty of the present study is a design that uses simple tooling and has been devised to repurpose alternative existing supply chains that are currently underused:

-

•

A3 clear polyvinylchloride/acetate sheets for the visor – printing/binding services

-

•

Medium density (~40 kgm−3) polyurethane foam for the facial support– upholstery/furniture manufacturers

-

•

Woven waistband elastic for the head strap - haberdashers

-

•

Staples & staplers to attach the strap– stationery/office-supply companies

-

•

Glue/adhesives to adhere the foam to the visor – crafting/home-improvement market

The dimensions of the design were finalised through consultation with end users; the width of A3 was found to simultaneously provide effective neck and forehead protection, whilst minimising cutting operations.

It should be noted that the materials and design outlined in this study are selected based on availabilities within the UK, and therefore different underused supply routes can be exploited elsewhere. For example, transparent plastic agricultural or roofing materials may be more widely available for the visor in rural locations, elasticated fishing lines or neoprene are likely to be more accessible for the strap in coastal locations.

The design is simple and easy to produce to allow distributed production by a workforce with limited manufacturing experience. The instructions for manufacture were shared electronically, and the raw materials were distributed between distinct manufacturing sites. Testing has revealed that a batched assembly line of individual operators performing specific tasks is ~50% more efficient than one-piece flow. This approach achieves a production rate of ~30 shields/person/h at an approximate cost of £0.40 per item. Limited tools beyond those found in a conventional office environment are required, and there is potential for the design to be modified and adapted to local availability. For example, the use of die cutting, guillotines, gluing jigs and strip cutters can drastically increase production rate and precision. An instructional video, description of production steps, cost breakdown and template are provided in the Supplementary material.

The design is simple and easy to produce to allow distributed production by a workforce with limited manufacturing experience. The instructions for manufacture were shared electronically, and the raw materials were distributed between distinct manufacturing sites. Testing has revealed that a batched assembly line of individual operators performing specific tasks is ~50% more efficient than one-piece flow. This approach achieves a production rate of ~30 shields/person/h at an approximate cost of £0.40 per item. Limited tools beyond those found in a conventional office environment are required, and there is potential for the design to be modified and adapted to local availability. For example, the use of die cutting, guillotines, gluing jigs and strip cutters can drastically increase production rate and precision. An instructional video, description of production steps, cost breakdown and template are provided in the Supplementary material.

One major concern over this production method is the cleanliness which can be achieved within unregulated environments. Consideration must also be given to potential COVID-19 contamination of the face shield by members of the workforce. In this regard, the following practical steps may be taken by producers and hospitals:

-

1.

Following production, the completed shields are sealed inside airtight packaging. Studies have shown that the COVID-19 virus can survive a maximum of 4 days on plastic surface [10] and therefore masks should be stored for 5 days prior to use.

-

2.

The face shields are being worn by hospital staff and therefore, a reduced level of cleanliness is required, than would be associated with patient use. Before use, the hospital will wipe and clean the shields in accordance with conventional good practice protocols for mass produced face shields.

The broader implication of this work is that designers should consider the sustainability and availability of supply chains when selecting materials and assembly methods during the production of emergency equipment such as PPE. The design presented may also prove useful to those interested in producing face shields to meet the arising needs of medical facilities across the world.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Simple medical face shield design.

Description of face shield including bill of materials and production method.

Acetate dimensions of face shield design.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2020.108749.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Alborz Shokrani: Writing - original draft, investigation, writing - review & editing. Evripides G. Loukaides: Conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, writing - review and editing. Edward Elias: Methodology, investigation. Alexander J.G. Lunt: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank clinicians at the Royal United Hospital in Bath, UK for their constructive feedback during the design of the face shields.

Data availability

All data required to reproduce these findings are available in the Supplementary material.

References

- 1.National-Association-of-Manufacturers . Manufacturers; The National Association of: 2020. NAM Coronavirus Outbreak Special Survey February/March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao B., Liu H. Vol. 2020. Bain & Company, Inc; 2020. China’s Supply Chains and Coronavirus: What’s Next?https://www.bain.com/insights/chinas-supply-chains-and-coronavirus-snap-chart/ [29/03/2020]; Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betti F., Ni J. How China Can Rebuild Global Supply Chain Resilience After COVID-19. 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/03/coronavirus-and-global-supply-chains/ [29/03/2020]; Available from.

- 4.Leonard J. Trump Eases PPE Export Ban With Canada, Mexico Exemption. 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-14/trump-team-eases-ppe-export-ban-with-canada-mexico-exemptions [14/04/2020]; Available from.

- 5.European-Commission . European Commision; Brussels: 2020. Coronavirus: Commission Bid to Ensure Supply of Personal Protective Equipment for the EU Proves Successful. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corera G. BBC; 28/03/2020. Coronavirus: UK Wary of International Market for Ventilators.https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-52074862 [29/03/2020] Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pooler M., Miller J., Kuchler H., Bushey C. The Ventilator Challenge Will Test Ingenuity to the Limit. 29/03/2020. https://www.ft.com/content/28bc27d1-8561-4838-bd71-0d7884a15dfa Available from.

- 8.McCue T.J. Forbes Media LLC; NewYork: 24/03/2020. Calling All Makers With 3D Printers: Join Critical Mission to Make Face Masks and Shields for 2020 Healthcare Workers.https://www.forbes.com/sites/tjmccue/2020/03/24/calling-all-makers-with-3d-printers-join-critical-mission-to-make-face-masks-and-shields-for-2020-healthcare-workers/#2ad461a77500 Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hitti N. Dezeen; 2020. MIT Develops One-Piece Plastic Face Shields for Coronavirus Medics.https://www.dezeen.com/2020/04/03/mit-covid-19-face-shields-design/ [13/04/2020]. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neeltje van Doremalen. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(16):1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Simple medical face shield design.

Description of face shield including bill of materials and production method.

Acetate dimensions of face shield design.

Data Availability Statement

All data required to reproduce these findings are available in the Supplementary material.