Highlights

-

•

There is a growing need for evidence on the effectiveness of different policies to promote physical activity.

-

•

We conducted a systematic literature review to collate the available evidence.

-

•

We identified 57 reviews with evidence on 53 types of physical activity policies from 7 areas.

-

•

There is a solid evidence base for the effectiveness of school-based and some infrastructural policies.

-

•

The evidence for other (e.g. economic) policies remains insufficient.

Keywords: Physical activity, Policy, Public health, Health policy, Review, Evidence, Effectiveness

Abstract

The importance of policy for promoting physical activity (PA) is increasingly recognized by academics, and there is a push by national governments and international institutions for PA policy development and monitoring. However, our knowledge about which policies are actually effective to promote PA remains limited. This article summarizes the currently available evidence by reviewing existing reviews on the subject.

Building on results from a previous scoping review on different types of PA-related evidence, we ran searches for combinations of the terms “physical activity”, “evidence”, “effect”, “review”, and “policy” in six different databases (PubMed, Scopus, SportDiscus, PsycInfo, ERIC, and IBSS). We used EPPI Reviewer 4 to further process the results and conduct an in-depth analysis.

We identified 57 reviews providing evidence on 53 types of policies and seven broader groups of policies. Reviews fell into four main categories: 1) setting- and target group-specific; 2) urban design, environment and transport; 3) economic instruments; and 4) broad-range perspective. Results indicate that there is solid evidence for policy effectiveness in some areas (esp. school-based and infrastructural policies) but that the evidence in other areas is insufficient (esp. for economic policies).

The available evidence provides some guidance for policy-makers regarding which policies can currently be recommended as effective. However, results also highlight some broader epistemological issues deriving from the current research. This includes the conflation of PA policies and PA interventions, the lack of appropriate tools for benchmarking individual policies, and the need to critically revisit research methodologies for collating evidence on policies.

1. Introduction

Both the scientific community and governments are increasingly recognizing the importance of policy for promoting physical activity (PA). In academia, bio-psycho-social and ecological models of health promotion highlight the importance of policy as a determinant of individual behavior (J. Sallis et al., 2008, Whitehead and Dahlgreen, 2006). Academia-driven guidelines for PA promotion (Rütten and Pfeifer, 2016) and advocacy documents such as the Toronto Charter (Global Advocacy Council for Physical Activity, 2010) also underscore the need for government action to increase population-level PA. Recent years have seen increased policy-making efforts by both national governments (e.g. the UK’s “Moving More, Living More” (HM Government and Mayor of London, 2014), “Get Ireland Active” (Healthy Ireland, 2016), and Australia’s “Sport 2030” (Australian Government, 2018)), and international institutions, (e.g. WHO’s PA Strategy for the European Region 2016–2025 (WHO Europe, 2015) and Global PA Action Plan (WHO, 2018); and the EU Council Recommendation on Health-Enhancing PA across Sectors (Council of the European Union, 2013)).

However, our overall knowledge about which specific policies are actually effective to promote PA remains rather limited. A recent scoping review conducted by Rütten et al. (2016) concluded that the PA research “landscape” continues to be dominated by literature dealing with the effects of PA on health or with the effectiveness of specific interventions to promote PA. It identified a total of 1246 reviews on evidence related to PA. Based on previous classification attempts (Brownson et al., 2009, Martin-Diener et al., 2014), reviews were sorted into three categories that reflect the progression of research from basic science (Type I: evidence on the health effects of PA) via intervention studies (Type II: evidence on the effectiveness of interventions to promote PA) to policy research (Type III: evidence on the effectiveness of policies implementing PA interventions). In a previous paper, the authors had pointed to the difference between physical inactivity as a public health issue and physical inactivity as a policy problem (Rütten et al., 2013). In this context, it is particularly relevant to distinguish PA policies (Type III) from PA interventions (Type II). The scoping review defined PA policy as “agendas, structures, funding and processes that affect development, implementation or adaptation of physical activity interventions” (Rütten et al., 2016). This view is supported by other authors, who usually characterize policy as formal or informal legislative or regulatory action, statements of intent, or guides to action issued by governments or organizations (Bellew et al., 2008, Bull et al., 2004, Sallis et al., 1998, Schmid et al., 2006). In other words, policies are not individual measures or actions to promote PA – they are not interventions but the framework in which interventions are tendered, developed, financed, or implemented, and it is therefore important to investigate the two separately.

All in all, only 40 of the 1246 reviews in the scoping review were classified as Type III (i.e. PA-policy related) evidence (Rütten et al., 2016). In addition, the review could only provide a broad overview but not a detailed analysis of the evidence. Therefore, our goal for the present paper was to add specifically to the evidence base about PA policy. We revisited the results of the scoping review and updated the Type III-search in order to obtain additional and more recent articles on the subject. In addition, we conducted an in-depth analysis of the policy-related reviews found in both searches. We were particularly interested in finding out which specific policies can currently be recommended as effective, and which areas, settings and target groups are most promisingly addressed by PA policies.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

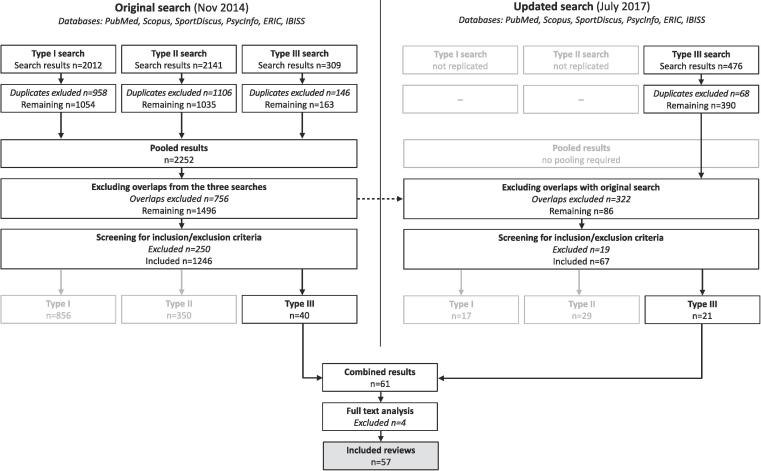

Fig. 1 provides an overview of the search procedure employed for this review. We updated parts of the original systematic search conducted for the scoping review by Rütten et al. (2016). This original search took place in November 2014. Initially, three separate searches were run, each combining a key term for a specific type of PA-related evidence (Type I: “health”; Type II: “intervention”; Type III: “policy”) with the terms “physical activity”, “evidence”, “effect”, and “review”. Two researchers independently searched the following databases: PubMed, Scopus, SportDiscus, PsycInfo, ERIC, and IBSS. Only documents in English, French, German and Spanish were considered for further analysis. After eliminating duplicates from the different databases, results from all three searches were pooled in order to eliminate overlapping results. Using EPPI Reviewer 4, a team of three researchers screened the remaining documents, eliminating those that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Results were excluded if they (a) did not deal with humans, (b) had no real connection to PA, or (c) were not reviews of any kind (e.g. if they were not systematic reviews, narrative reviews, non-systematic reviews). Results were then sorted into the three evidence types and further categorized based on the closest fit for each document. Importantly, reviews were filed into Type III if they dealt with policies based on the above-mentioned definitions, i.e. with overarching intentions/goals of governments or organizations and proposed strategies/courses of action to achieve them; articles were categorized as Type II if they dealt with specific measures to promote PA in order to achieve these goals. Though the original scoping review processed the results for all three evidence types to provide an overview of the “landscape” of PA research, it did not analyze the contents of the identified reviews.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart literature search.

All in all, the scoping review identified 856 reviews that pertained to Type I, 350 for Type II, and 40 for Type III (Rütten et al., 2016). For our in-depth analysis, we only considered the last category. To account for further documents published after November 2014, we conducted an update of the original search in July 2017. Since we were interested in the results pertaining to PA policies (Type III), we only re-ran the search combining the term “policy” with the general terms “physical activity”, “evidence”, “effect”, and “review” for our updated search. We sought to replicate the original search procedure as closely as possible, using the exact same databases, search strings, and database accounts employed in the original search. Duplicates and records already covered in the original search in 2014 were removed. The search update (2017) identified 21 additional documents. Using EPPI Reviewer 4, a team of two reviewers independently screened the remaining results based on the original inclusion/exclusion criteria, discussing differences to resolve contentious assessments.

2.2. Data extraction

Type III results from the original search (2014) and the updated search (2017) were combined for further analysis. Out of these 61 reviews, four were excluded during full text analysis: One did not meet the inclusion criteria and another was a duplicate; two results from the original scoping review could not be analyzed in detail as they had English abstracts but their main texts were in French and Spanish, respectively. As part of the analysis, we grouped the reviews into the following categories: Setting- and target-group-specific policies (see 3.2), urban design, environment and transport (see 3.3), economic policy instruments (see 3.4) and broad range reviews (see 3.5). Additionally, we built sub-categories where deemed appropriate. In a final step, two researchers conducted an in-depth analysis of the full texts of all reviews identified in the two search rounds. We extracted information on type of review, disciplinary background, main topic, main findings and the level of evidence that each review reported for the effectiveness of specific policies (strong, good, mixed/moderate, or insufficient). We developed a template to report results in a unified fashion (Smith et al., 2011). For each category, one researcher took the lead, compiling the main findings of studies into structured summaries. The other researcher then critically reviewed the information, and summaries were discussed to resolve conflicts.

3. Results

3.1. Overview

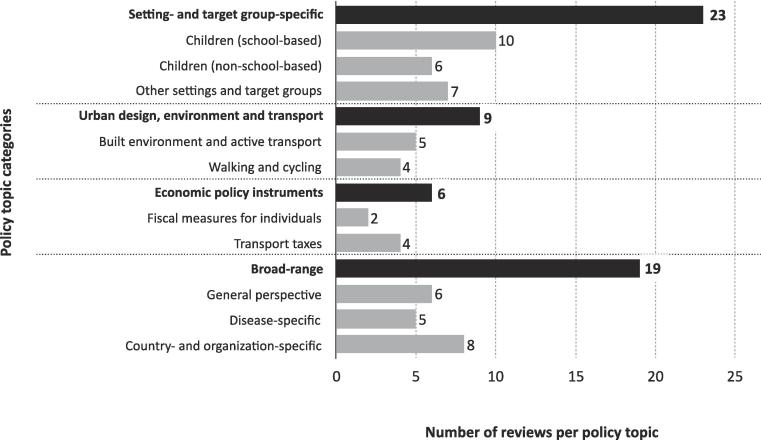

Overall, 57 documents were included in this review. As shown in Fig. 2, we identified four major categories of policy reviews: 23 reviews dealt with setting- and target group-specific policies; 9 with urban design, environment and transport policies; 6 with economic policy instruments; and 19 had a broad-range perspective covering multiple policies and/or perspectives.

Fig. 2.

Classification of reviews based on policies addressed.

Overall, the included reviews reported available evidence for 53 specific types of PA policy and seven groups of policies compiled from a general viewpoint or a disease-/country-specific perspective. Table 1 provides an overview of all policies, sources and their effectiveness as reported by the included reviews. The evidence available for the different policy categories is described in greater detail in the following sections.

Table 1.

Overview.

| Category | Sub-category | Types of policies reviewed | Source(s) | Evidence supporting effectiveness (as reported by source documents) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | Good/Available1 | Mixed/Moderate | Insuf-ficient | ||||

| Setting- and target-group-specific policies (23 reviews) | Children (school-based) (10 reviews) | State-level policies to promote PE | Robertson-Wilson et al., 2012 | X | |||

| School-level PA promotion policies | Metos and Murtaugh, 2011, Williams et al., 2013, Basch, 2011, Langford et al., 2014 | X | |||||

| Mandatory daily PE lessons | Hatfield and Chomitz, 2015 | X | |||||

| Mandatory PE lessons | Basch, 2010, Bassett et al., 2013, Hatfield and Chomitz, 2015, Yeh et al., 2010 | X | |||||

| Standardized curricula and ongoing PE teacher coaching | Hatfield and Chomitz, 2015, Bassett et al., 2013 | X | |||||

| Promoting active transport to school | Basch, 2010, Bassett et al., 2013, Hatfield and Chomitz, 2015 | X | |||||

| Extracurricular PA | Bassett et al., 2013, Hatfield and Chomitz, 2015, Kristensen et al., 2014 | X | |||||

| Structured use of recess | Basch, 2010, Bassett et al., 2013 | X | |||||

| Policies that discourage withholding recess | Hatfield and Chomitz, 2015 | X | |||||

| Leadership/accountability for school-based PA policies | Hatfield and Chomitz, 2015 | X | |||||

| Children (non school-based) (6 reviews) | Childcare centers: Staff education and behavior | Trost et al., 2010, Wolfenden et al., 2016 | X | ||||

| Childcare centers: Playground density | Trost et al., 2010 | X | |||||

| Childcare centers: Vegetation/open play areas | Trost et al., 2010 | X | |||||

| Active transport: general policies | Pate et al., 2011 | X | |||||

| Active transport: Traffic safety policies | Brennan et al., 2014 | X | |||||

| Community setting: Community environmental support | Pate et al., 2011 | X | |||||

| Community setting: Community design | Akinroye et al., 2014 | X | |||||

| Community setting: Mass media campaigns and advertising | Pate et al., 2011 | X | |||||

| Community setting: Organized sport | Akinroye et al., 2014 | X | |||||

| Central government strategies | Sember et al., 2016, Akinroye et al., 2014 | X | |||||

| Other settings & target groups (7 reviews) | Workplace: subsidies for health club use | Lin et al., 2014 | X | ||||

| Workplace: paid time for non-work-related PA | Lin et al., 2014 | X | |||||

| Workplace: on-site exercise facilities | Lin et al., 2014 | X | |||||

| Healthcare: Systems-level PA policies | Patrick et al., 2009 | X | |||||

| Healthcare: Financing changes to include PA | Patrick et al., 2009 | X | |||||

| Healthcare: System-wide implementation of PA counseling | Vuori et al., 2013, Nawaz et al., 2001 | X | |||||

| Sport: Large-scale sport events | Weed et al., 2012 | X | |||||

| Rural communities: Infrastructure policies | Umstattd Meyer et al., 2016a | X | |||||

| Black communities: School/childcare PA policies | Kumanyika et al., 2014 | X | |||||

| Black communities: Street design | Kumanyika et al., 2014 | X | |||||

| Black communities: Availability of parks/recreation facilities | Kumanyika et al., 2014 | X | |||||

| Urban design, environment and transport (9 reviews) | Built environment & active transport (5 reviews) | Urban environment changes | Barton, 2009 | X | |||

| Multi-level (infrastructure plus campaigns) | de Nazelle et al., 2011 | X | |||||

| High residential/employment density | de Nazelle et al., 2011 | X | |||||

| Mixed land use | Heath et al., 2006 | X | |||||

| Sidewalk quality/connectivity | Heath et al., 2006 | X | |||||

| Street redesign/lighting | Heath et al., 2006 | X | |||||

| Active travel policies | de Nazelle et al., 2011, Heath et al., 2006 | X | |||||

| Traffic calming/safety | Brown et al., 2017a | X | |||||

| Local planning/accessibility policies | Barton, 2009, Nieuwenhuijsen, 2016 | X | |||||

| Walking & Cycling (4 reviews) | Walking: Social marketing/messaging | Mulley and Ho, 2017 | X | ||||

| Walking: Infrastructures to support dog-walking | Christian et al., 2017 | X | |||||

| Cycling: Cycle routes | Fraser and Lock, 2011 | X | |||||

| Cycling: Separation of cycling from other traffic | Fraser and Lock, 2011 | X | |||||

| Cycling: High population density | Fraser and Lock, 2011 | X | |||||

| Cycling: Short trip distance | Fraser and Lock, 2011 | X | |||||

| Cycling: Promimity of cycle paths/green spaces | Fraser and Lock, 2011 | X | |||||

| Cycling: Projects to promote active transport to school | Fraser and Lock, 2011, Stewart et al., 2015 | X | |||||

| General road-use/parking pricing policies | de Nazelle et al., 2011 | X | |||||

| Economic policy instruments (6 reviews) | Fiscal measures for individuals (2 reviews) | Subsidies and tax credits to encourage individual PA | Cawley, 2015, Faulkner et al., 2011, Sturm and An, 2014 | X | |||

| Taxpayer’s indirect subsidies to provide PE in schools | Cawley, 2015 | X | |||||

| Transport taxes (4 reviews) | Congestion pricing schemes | Brown et al., 2015, Shemilt et al., 2013, Faulkner et al., 2011 | X | ||||

| Fuel taxation/pricing | Brown et al., 2017b | X | |||||

| Broad range (19 reviews) | General perspective (6 reviews) | School-based policies for children | Owen et al., 2006, Heath et al., 2012 | X | |||

| Urban design, environment and transport policies | Der Ananian and Ainsworth, 2013, Heath et al., 2012, Sallis et al., 1998 | X | |||||

| Implementation conditions for PA policies | Horodyska et al., 2015 | X | |||||

| Economic effectiveness of PA policies/environmental interventions | McKinnon et al., 2015 | X | |||||

| Disease-specific (5 reviews) | PA-related policies to counteract cardiovascular diseases | Matson-Koffmann et al., 2005, Jørgensen et al., 2012, Dodson, 2008, Cawley, 2016 | X | ||||

| PA-related policies to counteract obesity | Dodson, 2008, Cawley, 2016, Olstad et al., 2017 | X | |||||

| Country- & organisation-specific (8 reviews) | Country- and organization-specific policies | Bellew et al., 2008, Shill et al., 2012, Dietz, 2015, Mowen and Baker, 2009, Després et al., 2014, Knai et al., 2015, Echouffo-Tcheugui and Kengne, 2011, Wiseman, 2010 | X | ||||

1Some reviews report “good” evidence for certain policies; others merely report that “there is” evidence or that evidence supportive of effectiveness is “available”.

3.2. Setting- and target group-specific policies

As shown in Table 2, 23 reviews were identified that deal with setting- and target group-specific PA promoting policies. Most of the reviews (16) cover policies for children and adolescents, either within (3.2.1) or outside (3.2.2) the school setting. Only seven reviews focus on other target groups and settings, such as the workplace or the healthcare system (3.3.3).

Table 2.

Setting- and target group-specific policies.

| Review | Title | Main topic | Type of review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children (school-based) | |||

| Basch, C. (2011) | Healthier students are better learners (Journal of School Health) | Identifying health problems in schoolchildren that lead to low academic performance | Narrative review |

| Basch, C. (2010) | Healthier students are better learners (Research Review) | Identifying health problems in schoolchildren that lead to low academic performance | Narrative review |

| Bassett, D.R. et al. (2013) | Estimated energy expenditures for school-based policies and active living | Assessment of the increase in energy expenditure in children caused by certain environmental/policy interventions in schools | Systematic review |

| Hatfield, D. P. & Chomitz, V. R. (2015) | Increasing Children's Physical Activity During the School Day | Identifying evidence-based approaches for increasing children's PA throughout the school-day and the multilevel factors that support implementation | Narrative review |

| Kristensen A. et al. (2014a) | Reducing childhood obesity through US federal policy | Estimate the impact of three federal policies by using microsimulation; modeling calculates effects if programs were offered to all youths for one year | Narrative review |

| Langford R. et al. (2014) | The WHO health promoting school framework | Assessing the effectiveness of the WHO Health Promoting Schools framework in improving health and academic achievement of students | Systematic review |

| Metos J & Murtaugh M (2011) | Words or reality: Are school district wellness policies implemented? | Assessing whether school wellness policies are written and implemented as a result of the 2004 US Child Nutrition Reauthorization Act CNRA | Systematic review |

| Robertson-Wilson JE et al. (2012) | Physical activity politics and legislation in schools | Reviewing state and federal level policy in the US that attempted to promote PA in schools and determining their impact | Systematic review |

| Williams A et al. (2013) | Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between childhood overweight and obesity and primary school diet and physical activity policies | Assessing the effect of diet/PA policies on children's weight status | Systematic review |

| Yeh M (2010) | Effectiveness of school-based policies to reduce childhood obesity | Identifying school-based interventions, environmental interventions, school policies, and public policies to reduce childhood obesity | Narrative review |

| Children (non school-based) | |||

| Brennan, L. K. et al. (2014) | Childhood obesity policy research and practice | Systematically assessing the effectiveness of different policies and environmental strategies to reduce childhood obesity | Narrative review |

| Pate R. et al. (2011) | Policies to increase physical activity in children and youth | Identifying common international policies to increase PA in children/adolescents, and examining if they are supported by scientific evidence | Systematic review |

| Akinroye, K. K. et al. (2014) | Results from Nigeria’s 2013 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth | Summarizing available evidence on the status of PA in children and adolescents in Nigeria | Narrative review |

| Sember, V. et al. (2016) | Results From the Republic of Slovenia’s 2016 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth | Summarizing Slovenia's efforts to report PA/PA standards for children and youths | Unsystematic review |

| Wolfenden, L. et al. (2016) | Strategies to improve the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies, practices or programmes within childcare services | Examining the effectiveness of strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices and programs by childcare services to promote health eating, PA and/or obesity prevention | Systematic review |

| Trost, S. et al. (2010) | Effects of child care policy and environment on physical activity | Evaluating the influence of child care policy and environments on PA in pre-school children | Unsystematic review |

| Other settings and target groups | |||

| Kumanyika S. et al. (2014a) | Examining the evidence for policy and environmental strategies to prevent childhood obesity in black communities | Assessing whether an existing review system for policy and environmental strategies to prevent childhood obesity also works for black Americans | Unsystematic review |

| Lin Y et al. (2015) | An integrative review: Work environment factors associated with physical activity among white-collar workers | Sythesizing evidence for the role of the work environment (incl. workplace PA policies) in explaining PA levels | Unsystematic review |

| Nawaz H. & Katz D. (2001) | American College of Preventive Medicine practice policy statement: weight management counselling of overweight adults | Providing policy guidance on weight loss counseling for adults by health professionals | Narrative review |

| Patrick K et al. (2009) | The healthcare sector's role in the US national physical activity plan | Identifying opportunities to promote PA in healthcare settings for the “upcoming” US National PA plan | Narrative review |

| Umstattd Meyer, M. R. et al. (2016) | Physical Activity-Related Policy and Environmental Strategies to Prevent Obesity in Rural Communities: A Systematic Review of the Literature, 2002–2013 | Synthesizing evidence on the implementation, relevance and effectiveness of PA-related policy and environmental strategies for obesity prevention in rural communities | Systematic review |

| Vuori I et al. (2013) | Physical activity promotion in the health care system | Informing healthcare practitioners what can be done in the healthcare setting to promote PA | Narrative review |

| Weed M et al. (2012) | Developing a physical activity legacy from the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games | Examining potential processes by which the London 2012 Olympics might deliver a PA-related “legacy” | Systematic review |

3.2.1. PA promotion for children and adolescents within the school setting

We found ten reviews that addressed PA promoting policies for children within the school setting. Five of these evaluated overarching public policies (Basch, 2011, Langford et al., 2014, Metos and Murtaugh, 2011, Robertson-Wilson et al., 2012, Williams et al., 2013). Evidence from the US suggests that policies at the state level can result in an increase in the number of physical education (PE) specialists in schools as well as in additional policies against using PA as a form of punishment in schools (Robertson-Wilson et al., 2012). However, written PA promotion policies do not always translate into school practice (Metos and Murtaugh, 2011), and they do not necessarily have an impact on students’ Body-Mass Index or Standard Deviation Score (Williams et al., 2013). One review (Basch, 2011) concluded that school-level PA policies are promising in principle but often lack sufficient financing, program quality, and effective coordination, while another (Langford et al., 2014) found only moderate effects of school-level PA policies using WHO’s Health Promoting Schools framework.

Four reviews dealt with policies targeting physical education lessons in schools (Basch, 2010, Bassett et al., 2013, Hatfield and Chomitz, 2015, Yeh et al., 2010). The evidence showed that PA can be promoted by making participation in PE mandatory (Basch, 2010, Bassett et al., 2013, Yeh et al., 2010) and through measures that increase the quality and consistency of PE classes, such as standardized PE curricula or ongoing coaching for PE teachers (Hatfield and Chomitz, 2015, Bassett et al., 2013). Daily mandatory PE lessons can increase students’ moderate-to-vigorous PA by more than 20 min per day (Hatfield and Chomitz, 2015).

A number of reviews analyzed other policies in the school setting. The evidence suggests that policies promoting active transport to school as part of a multi-component approach can be effective (Basch, 2010, Bassett et al., 2013). Extracurricular PA before or after school can increase students’ moderate-to-vigorous PA by up to 25 min per day (Bassett et al., 2013, Hatfield and Chomitz, 2015, Kristensen et al., 2014), and participation rates are higher when no school policy exists that requires specific academic or attendance standards from all participants (Hatfield and Chomitz, 2015). The structured use of recess can be another effective policy (Basch, 2010, Bassett et al., 2013); policies that discourage withholding recess seem to have an impact on every-day school practices in this regard (Hatfield and Chomitz, 2015). In addition, leadership and accountability for PA policies and initiatives influence implementation (Hatfield and Chomitz, 2015).

3.2.2. PA promotion for children and adolescents outside the school setting

Six reviews pertain to PA promoting policies for children outside the school setting (Akinroye et al., 2014, Brennan et al., 2014, Pate et al., 2011, Sember et al., 2016, Wolfenden et al., 2016). Three of these investigated policies in the childcare setting and found evidence for their effectiveness (Brennan et al., 2014, Trost et al., 2010, Wolfenden et al., 2016). In particular, staff education and training, staff behavior on the playground, a low density of individuals on playgrounds and the presence of vegetation and open play areas seem to have a positive influence on the moderate-to-vigorous PA of children (Trost et al., 2010, Wolfenden et al., 2016).

The promotion of active transport for children and adolescents was included in two reviews, finding moderate evidence for transport policy in general (Pate et al., 2011) and rating traffic safety policies in particular as “promising” (Brennan et al., 2014).

PA policies in the community setting were part of two reviews. One of them found that, globally, the evidence for community environmental support was limited/inconclusive (Pate et al., 2011), while the other concluded that there was insufficient evidence for the influence of community and the built environment on PA among children and youth in Nigeria (Akinroye et al., 2014). According to one review (Pate et al., 2011), there is strong evidence for policies focusing on mass media and advertising campaigns directed towards children and adolescents, while no evidence was found regarding the frequency of participation in organized sport and PA outside school for children and youth in Nigeria (Akinroye et al., 2014).

One review (Sember et al., 2016) found evidence for the effectiveness of central governmental strategies directed toward children and adolescents in Slovenia. Data collected via a nationwide monitoring system (SLOfit) showed declining obesity trends and improving fitness of primary school children over time. The authors argue that this indicates the effectiveness of centralized governmental policies such as Slovenia’s National Program of Nutrition and Physical Activity for Health, the National Program of Sport, the Centre for School and Outdoor Education program and the PA intervention program Healthy Lifestyle (Sember et al., 2016). By contrast, another review found no evidence for the effectiveness of national government policy for children and adolescents in Nigeria (Akinroye et al., 2014).

3.2.3. Other settings and target groups

Seven reviews addressed PA promotion policies for settings other than schools or for target groups other than children and adolescents. One article reviewed the workplace setting (Lin et al., 2014), finding evidence that supportive workplace PA policies such as subsidies for health club use, paid time for non-work-related PA, and providing access to on-site exercise facilities can have a positive impact on employees’ PA levels (Lin et al., 2014).

Three articles reviewed PA policies targeting patients in the healthcare setting (Nawaz et al., 2001, Patrick et al., 2009, Vuori et al., 2013), suggesting that the evidence on policies in this setting is mixed (Patrick et al., 2009), while the systems-wide implementation of PA counseling could be an efficient, effective and cost-effective way to promote PA (Vuori et al., 2013, Nawaz et al., 2001). One article dealt with PA policies in the sport setting (Weed et al., 2012), finding that sport events such as the 2012 Olympic Games in London can generate a “festival effect” and thus impact PA levels. Another review found that in rural communities, PA policies promoting the enhancement of biking and walking infrastructures or improved access to outdoor recreational facilities can be effective (Umstattd Meyer et al., 2016b).

One article focused on PA policies reaching black communities in the US (Kumanyika et al., 2014); the evidence suggests that policies pertaining to schools and childcare are effective, whereas findings did not support the effectiveness of street design or the availability of park and recreation facilities (Kumanyika et al., 2014).

3.3. Urban design, environment, transport

Nine reviews on transport policies and urban design were identified (Table 3). These reviews either deal with the built environment and active transport policies in general, or with walking or cycling in particular.

Table 3.

Urban design, environment & transport.

| Review | Title | Main topic | Type of review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barton, H. (2009) | Land use planning and health and well-being | Influence of land use planning on health; this includes lifestyle choices in relation to PA, diet, mental health, income, pollution, etc. PA-related aspects include effects of the (built) environment on PA levels, active travel, and active recreation | Narrative review |

| Brown, V. et al. (2017a) | Evidence for associations between traffic calming and safety and active transport or obesity: A scoping review | Reviewing the evidence for the association between traffic calming/safety measures and PA/obesity | Scoping review |

| de Nazelle, A. et al. (2011) | Improving health through policies that promote active travel | Investigating the relationship between policy changes/environmental interventions and active travel, thus identifying effective policies/interventions | Narrative review |

| Fraser, S. & Lock, K (2011) | Cycling for transport and public health | Determining the impact of active transport “strategies” that modify the built environment on PA levels | Systematic review |

| Heath, G. et al (2006) | The effectiveness of urban design and land use and transport policies and practices to increase physical activity | Gathering systematic information on which “environmental and policy interventions” are most effective to promote PA | Systematic review |

| Christian, H. E. et al. (2017) | Transport and Sustainability: Dog Walking | Reviewing the evidence on the relationship between external factors (esp. the environment) and dog-walking, incl. “overarching” policy | Narrative review |

| Mulley, C. & Ho, C. (2017) | Understanding the determinants of walking as the basis for social marketing public health messaging | Understanding the connection of policy to promote PA and the determinants of walking, and identifying the policy levers that could be used to increase walking time | Narrative review |

| Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. (2016) | Urban and transport planning, environmental exposures and health-new concepts, methods and tools to improve health in cities | Summarize new insights into links between built environment and health, identifying new concepts, methods and tools to inform science and policies | Unsystematic review |

| Stewart, G. et al. (2015) | What interventions increase commuter cycling? A systematic review | Identifying interventions that will increase commuter cycling, including “environmental interventions” | Systematic review |

3.3.1. Built environment & active transport policies

Five reviews address the influence of active travel policies and the built environment on PA and health. One of them focuses on health from a general point of view (Nieuwenhuijsen, 2016), while the others have a stronger focus on PA (Barton, 2009, Brown et al., 2017a, de Nazelle et al., 2011, Heath et al., 2006). The evidence from these four suggests that the urban environment can have a positive impact on active transport and thus on PA levels (Barton, 2009). PA can be promoted especially by multi-level interventions that combine infrastructure improvements with promotional campaigns (de Nazelle et al., 2011), by a high residential or employment density (de Nazelle et al., 2011), by mixed land use, sidewalk quality/connectivity, as well as by redesigning streets and improving lighting (Heath et al., 2006). Inconclusive evidence exists regarding the effectiveness of active travel policies – while one review describes a positive impact (de Nazelle et al., 2011), another (albeit older) one states that there is an insufficient number of studies (Heath et al., 2006). One review analyzed traffic calming/safety measures, but also only found inconclusive evidence: just 9 out of 59 studies reported that these policies have a positive association with levels of active transport (Brown et al., 2017a). The evidence regarding local policies is also mixed: While one review found community-level urban and transport planning to be promising and cost-effective (Nieuwenhuijsen, 2016), another found no evidence for the effectiveness of local policies stipulating PA infrastructure accessibility criteria, e.g. that dwellings should be within 400 m of a bus stop (Barton, 2009).

3.3.2. Walking and cycling

Two reviews analyzed policies and environmental changes that promote walking (Christian et al., 2017, Mulley and Ho, 2017). The evidence suggests that social marketing public health messages can be effective to promote walking (Mulley and Ho, 2017). Furthermore, levels of dog-walking are influenced by the built and policy environment, such as access to attractive public spaces with a dog-supportive infrastructure, like trash cans and dog waste bags (Christian et al., 2017).

Two systematic reviews analyzed the effect of the environment on cycling (Fraser and Lock, 2011, Stewart et al., 2015). The evidence indicates that the presence of dedicated cycle routes, the separation of cycling from other traffic, high population density, short trip distance, the proximity of a cycle path or green space and projects that aim at increasing active transport to school can promote cycling (Fraser and Lock, 2011). An analysis of single policies, by contrast, had ambivalent results: While the opening of a bridge in Glasgow increased the number of cyclists by 47.5%, an Irish program including infrastructural changes and financial incentives could not be shown to be effective (Stewart et al., 2015).

Additionally, one review covered other policies such as road and parking pricing as well as policies to improve public transport in general (de Nazelle et al., 2011). The evidence suggests that these policies have a positive effect on walking and cycling.

3.4. Economic policy instruments

As shown in Table 4, six reviews dealing with economic policy instruments for promoting PA were identified. The specific topics covered can be divided into two major categories: subsidies to directly increase individuals’ PA and taxes to facilitate a modal shift in transport behavior at the population level.

Table 4.

Economic policy instruments.

| Review | Title | Main topic | Type of review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brown, V. (2017b) | Obesity-related health impacts of fuel excise taxation- an evidence review and cost-effectiveness study | Reviewing the evidence for the effects of fuel taxation on PA and obesity | Scoping review |

| Brown, V. et al. (2015) | Congestion pricing and active transport – evidence from five opportunities for natural experiment | Examining the effects of congestion pricing schemes on PA and its health benefits | Unsystematic review |

| Cawley, J. (2015) | An economy of scales: A selective review of obesity's economic causes, consequences, and solutions | Reviewing the economic causes/consequences of obesity and potential economic instruments to solve it | Narrative review |

| Faulkner, G. et al. (2011) | Economic instruments for obesity prevention | Synthesizing evidence on impact of economic policies targeting obesity and its causes (incl. PA) | Scoping review |

| Shemilt I et al. (2013) | Economic instruments for population diet and physical activity behavior change | Analyze emprical studies on use of economic instruments to promote dietary and PA behavior change | Systematic scoping review |

| Sturm, R. & An, R. (2014) | Obesity and economic environments | Summarizing the current understanding of economic factors of the obesity epidemic, including policy approaches | Narrative review |

3.4.1. Fiscal measures for individuals

Two reviews dealt with the effectiveness of direct fiscal measures to promote PA in individuals (Cawley, 2015, Faulkner et al., 2011, Sturm and An, 2014). There seem to be no examples for direct taxes penalizing obesity/physical inactivity, only subsidies and tax credits to encourage individuals to engage in more PA (Cawley, 2015). While some of these instruments (e.g. fostering the participation of “targeted populations”) seem to be more promising than others (e.g. the Canadian “Children’s Fitness Tax Credit”), the overall evidence is insufficient (Faulkner et al., 2011, Sturm and An, 2014). Another policy instrument that was addressed were indirect subsidies that taxpayers provide to co-finance PE in schools. The reviews do not report on the effectiveness of these subsidies directly, but Cawley identifies several studies from the US suggesting that PE as such does not have a significant effect on students’ weight loss in most grades (Cawley, 2015).

3.4.2. Transport taxes

Four reviews investigated the effectiveness of congestion pricing schemes (Brown et al., 2015, Faulkner et al., 2011, Shemilt et al., 2013) and fuel taxation/prices (Brown et al., 2017b, Faulkner et al., 2011). Evidence from Singapore, London, Stockholm and Gothenburg suggests an increase of human-powered transport and public transport use after the introduction of congestion pricing (Brown et al., 2015). However, results substantially vary in magnitude, and the authors concede that a number of variables (e.g. improvements in bus services made at the same time as the congestion tax was imposed) may confound the results, and the overall evidence base remains ambiguous (Brown et al., 2015). There is some evidence for a positive relationship between fuel taxation/prices and PA, but again, study results are mixed due to potential confounders (e.g. public policies that facilitate car ownership may also influence the level of car use (Brown et al., 2017b)). Furthermore, the findings of Brown et al. suggest that increased fuel prices may have a positive effect on active transport and population health (Brown et al., 2017b). The other two reviews found only inconclusive evidence (Faulkner et al., 2011, Shemilt et al., 2013).

3.5. Broad-range reviews

We identified 19 reviews that provide more general assessments of policy effectiveness (Table 5), either from an overarching perspective or from a disease- or country-specific point of view. They contain several policies that were already reported above, but they are usually not detailed enough to be sorted into a specific category/sub-category or to add substantially new evidence regarding individual policies. They are therefore reported separately here.

Table 5.

Broad range policies.

| Review | Title | Main topic | Type of review |

|---|---|---|---|

| General perspective | |||

| Der Anain, C.. & Ainsworth B. (2013) | Population based approaches for health promotion | Review recent comprehensive lit reviews on evidence-based population-based approaches for PA promotion (“environmental and policy-based approaches”) | Narrative review |

| Heath G. et al. (2012) | Evidence-based intervention in physical activity | Identify effective, promising, and emerging interventions to promote PA across the world | Narrative review |

| Horodyska, K. et al. (2015) | Implementation conditions for diet and physical activity interventions and policies: an umbrella review | Identifying evidence-based conditions important for successful implementation of interventions and policies promoting healthy diet and PA | Umbrella review |

| McKinnon, R. A. et al. (2015) | Obesity-Related Policy/Environmental Interventions: A Systematic Review of Economic Analyses | Summarizing the results of cost-effectiveness studies of obesity-related policy/environmental interventions | Systematic review |

| Owen N. et al. (2006) | Evidence-based approaches to dissemination and diffusion of physical activity interventions | Providing conceptual foundations and case examples of diffusion of PA interventions, accompanied by some recommendations for public policies to facilitate diffusion | Narrative review |

| Sallis J et al. (1998) | Environmental and policy interventions to promote physical activity | Reviewing select “environmental and policy interventions” to promote PA to build a model for PA and its environmental/policy determinants | Unsystematic review |

| Disease-specific perspective | |||

| Cawley, J. (2016) | Does Anything Work to Reduce Obesity? (Yes, Modestly) | Reviewing the effectiveness of anti-obesity programs | Narrative review |

| Dodson, E. (2009) | Can policy facilitate health decision making to increase physical activity and prevent obesity? | Examining different types of policy interventions to increase PA and improve chronic disease prevention | Narrative review |

| Jorgensen et al. (2012) | Population-level changes to promote cardiovascular health | Assisting authorities in selecting management strategies for CVD, focusing on fiscal measures, national/regional policies, and environmental changes; Covers food, PA, smoking, alcohol; | Narrative review |

| Matson-Koffmann D et al. (2005) | A site-specific literature review of policy and environmental intervention that promote physical activity and nutrition for cardiovascular health | Determining whether “policy and environmental interventions” can increase PA and improve nutrition | Unsystematic review |

| Olstad, D. L. et al. (2017) | Can targeted policies reduce obesity and improve obesity-related behaviours in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations? A systematic review | Synthesizing evidence on the impact of targeted policies on anthropometric, diet and PA outcomes among socially disadvantaged children and adults | Systematic review |

| Country- and organization-specific perspective | |||

| Bellew, B. et al. (2008) | The rise and fall of Australian physical activity policy | Development of PA policy in Australia over a decade and comparison of this development to other countries | Narrative review |

| Despres, J. P. et al. (2014) | Worksite health and wellness programs: Canadian achievements & prospects | Reviewing evidence about health and wellness program delivery systems in Canada, esp. “relevant legislative and policy initiatives to create a context conducive to improve the healthfulness of Canadian workplaces” | Narrative review |

| Dietz, W. H. (2015) | The response of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to the obesity epidemic | Chronicling the steps of the CDC to address the obesity epidemic and document progress, incl. legislative, regulatory and voluntary initiatives by the federal administration | Narrative review |

| Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B. & Kengne, AP (2011) | Chronic non-communicable diseases in Cameroon – burden, determinants and current policies | Identify frequency, determinants and consequences of NCDs in Cameroon and identify research, intervention and policy gaps (i.e. no limitation to PA or to type III evidence) | Narrative review |

| Knai, C. et al. (2015) | Getting England to be more physically active: are the Public Health Responsibility Deal's physical activity pledges the answer? | Analyzing the effects of the “Responsibility Deal” PA pledges (PPP) initiative by the English health authorities on motivating organizations to become active in PA promotion | Narrative review |

| Mowen AJ & Baker BL (2009) | Park, recreation, fitness, and sport sector recommendations for a more physically active America | Assessing the potential of the “park, recreation, fitness and sport sector” to help addressing PI in the US | Narrative review |

| Shill J et al. (2012) | Regulation to create environments conducive to physical activity | Understanding the barriers and facilitators for PA policies at the Australian state government level | Narrative review |

| Wiseman M (2010) | Deriving Policy from evidence | Considering important points related to finding the best available evidence for health promotion (incl. PA) with a focus on cancer, and the processes best use to identify and use evidence for policy | Narrative review |

3.5.1. General perspective reviews

Six reviews analyzed various types of policies from a general point of view, covering multiple target groups, settings, and topics (Der Ananian and Ainsworth, 2013, Heath et al., 2012, McKinnon et al., 2016, Owen et al., 2006, Sallis et al., 1998), focusing on policy implementation (Horodyska et al., 2015), or investigating cost-effectiveness (McKinnon et al., 2016). Results suggest that school-based PA policies for children (esp. PE policies) can be considered effective (Heath et al., 2012, Owen et al., 2006). The same holds for urban design, environment and transport policies (Der Ananian and Ainsworth, 2013, Heath et al., 2012, Sallis et al., 1998), although more research may be required (Der Ananian and Ainsworth, 2013). Horodyska et al. conclude that the successful implementation of PA policies requires factors such as political support, cross-sectoral collaboration and the involvement of stakeholders at multiple levels (Horodyska et al., 2015). McKinnon et al. found that studies on the cost-effectiveness of different PA policies and environmental interventions generally reported beneficial economic outcomes (McKinnon et al., 2016).

3.5.2. Disease-specific reviews

Five reviews investigated PA promoting policies from a disease-specific perspective. Two of them found evidence for the effectiveness of PA-related policies regarding cardiovascular health, specifically policies that promote workplace PA, PE in schools, and access to spaces for PA (Matson-Koffmann et al., 2005), as well as pricing and infrastructure policies that promote active transport (Jørgensen et al., 2012). However, most studies included in these two reviews focused exclusively on PA levels, with only two studies reporting more direct health-related outcome variables such as aerobic power, reduced blood pressure, and overweight (Matson-Koffmann et al., 2005). Three reviews dealt with PA-related policies to prevent obesity. They found evidence for the effectiveness of workplace (Cawley, 2016, Dodson, 2008), and school-based (Olstad et al., 2017) PA policies but only mixed evidence for government policies to prevent obesity among children (Olstad et al., 2017).

3.5.3. Country- and organization-specific reviews

Eight reviews analyzed PA promoting policies from a country- or organization-specific perspective. Seven of them focused on policies in Australia (Bellew et al., 2008, Shill et al., 2012), the United States (Dietz, 2015, Mowen and Baker, 2009), Canada (Després et al., 2014), England (Knai et al., 2015) and Cameroon (Echouffo-Tcheugui and Kengne, 2011). One of the reviews deals with a report by the World Cancer Research Fund and the American Institute for Cancer Research that developed recommendations for PA and nutrition (Wiseman, 2010). As these reviews either describe the historical development of PA policy in a country (Bellew et al., 2008, Després et al., 2014) or analyze very specific policies such as the Public Health Responsibility Deal’s PA pledges in England (Knai et al., 2015), it is hard to derive general conclusions from the research.

4. Discussion

The main aim of this systematic review of reviews has been to provide an overview about the available evidence on PA-promoting policies. To our knowledge, it thus fills an important gap in the current PA research and provides an added value compared to the scoping review by Rütten et al. (2016), which was not in a position to comprehensively analyze the content of the identified reviews. A look at the central categories identified from this review shows that there is a focus on policies that promote PA for specific target groups (esp. children and adolescents) and policies that make changes to the built environment and transport infrastructures/systems. There is also an interest in fiscal instruments, an area that is arguably underdeveloped in PA promotion when compared to the other “big three” areas of NCD prevention, tobacco, alcohol and nutrition.

Further aggregating the results shown in Table 1 to conclude whether PA policy is ‘generally’ effective in a certain category is difficult. However, our results suggest that there is a rather solid body of evidence for the effectiveness of policies in certain areas, e.g. for children in the school-setting and for the promotion of walking and cycling. For several other categories, the evidence is mixed, with a number of reviews suggesting effectiveness and others only finding moderate or insufficient evidence. This appears to apply to the non-school setting for children, to policies for other settings and target groups, and to policies targeting the built environment/active transport. This latter sub-category is interesting as the evidence is apparently “strong” for some measures but mixed or insufficient for others. This may be due to the limited number of reviews on which the evidence is based and the specific methods used therein. An alternative interpretation could be that there is good evidence for the effects of specific changes to the environment (e.g. street lighting and mixed land use) but not necessarily for broader infrastructure policies (e.g. active travel or traffic calming/safety policies; see also the discussion on interventions vs. policies below). Finally, there currently seems to be no solid evidence that economic policy instruments are effective to promote PA. The evidence is only moderate/mixed for transport taxes and seems to be entirely insufficient when it comes to fiscal measures targeted directly at individuals.

All in all, the following types of policies can currently be recommended based on the available evidence: school policies for children and adolescents that make PE lessons mandatory and that support interventions for extracurricular PA, policies that support mass media campaigns and advertising to promote PA among children in the community setting, and infrastructure policies that promote interventions improving aspects of the built environment (incl. residential/employment density, mixed land use, sidewalk quality and connectivity, and street redesign). This apparent “dominance” of school and infrastructure policies in the evidence base may raise the question of whether these policies are truly more effective or whether it is simply easier to show policy effectiveness in these settings. There may be a bias towards closed settings (such as the school setting), where a causality between policy and PA-related outcomes can be assumed with greater confidence, or towards settings for which PA-related proxy measures can be more easily obtained (such as use of certain types of transport). Additional research using innovative theoretical concepts and measurement approaches (e.g. including capabilities for PA in addition to PA levels; see Sen, 1992, Abel and Frohlich, 2012) should be conducted to address these questions. Additionally, it is important to closely analyze the conditions under which recommended policies can be most effective and to address potential unintended adverse effects prior to implementation. For example, school-based policies need to ensure that extracurricular activities are modestly priced or free of charge in order not to exclude children from lower-income families. Likewise, PA infrastructure policies may exacerbate social inequalities by targeting (only) well-off neighborhoods or by failing to take into account the specific needs of disadvantaged populations.

There are some limitations to this study. First, from a biomedical perspective, the number of systematic reviews identified (n = 13) may seem low compared to the number of unsystematic (n = 8) and narrative reviews (n = 30). One might argue that the quality of the overall evidence is not sufficient to draw any meaningful conclusions. However, since most policies are difficult to evaluate using controlled designs, it is only natural that many reviews could not be systematic.

A systematic appraisal for review quality is currently lacking. On the one hand, this undoubtedly implies that results have to be interpreted with caution, as not all reviews were conducted using the same process. On the other hand, applying established quality standards such as AGREE (Cluzeau et al., 2003) to evaluate the quality of individual reviews is challenging given that the vast majority are non-systematic reviews. As stated above, excluding pieces of policy research based on criteria developed for biomedical research would fail to recognize the inherently different nature of policy and policy research.

It should also be noted that, based on the original scoping review, we classified policies mostly based on their settings, target groups, and main policy instruments (e.g. financial incentives and infrastructure changes). While we consider this taxonomy useful, it is important not to lose sight of other important factors that may determine the effectiveness of policies regardless of their contents. These include the institutional, political, and social context of polices, the actors and processes involved in policy development and implementation, as well as the resources dedicated to the policies. Investigating the evidence on the basis of some of these variables could be a worthwhile endeavor for future research.

The methodological challenges also point to a number of important broader epistemological questions inherent in the existing PA policy literature. From a political science perspective, gathering evidence using the medically-based tool of systematic reviews/reviews of reviews may not be sufficient to compile all the available evidence. Additional strategies may be required to supplement the current results and capture more of the existing social science literature on the issue. This could include using more social science databases, searching for studies rather than reviews, conducting extensive hand searches for books, book chapters, and grey literature, or critically revisiting search terms which may be more commonly used in the public health literature than in political science (such as “effectiveness”).

Additionally, we observed a conflation of “policies” (Type III evidence) and “interventions” (Type II) to promote PA. This was also previously pointed out in the scoping review by Rütten et al. (2016) and further confirmed when we reviewed the documents for this systematic review. As outlined above, theory clearly distinguishes between a policy and the specific measures it stipulates (policy contents). In the literature, however, there are numerous examples where this distinction is not made, especially in the field of PA infrastructures. Several documents even explicitly subsume both policy and environmental interventions into one category (e.g. Barton, 2009, Christian et al., 2017, Heath et al., 2006, Kumanyika et al., 2014, Matson-Koffmann et al., 2005, McKinnon et al., 2016, Sallis et al., 1998, Stewart et al., 2015, Umstattd Meyer et al., 2016b), or they consider “policy” to be simply another type of intervention (e.g. Akinroye et al., 2014, Brown et al., 2017a, Horodyska et al., 2015, Mulley and Ho, 2017). This problem may also partially explain one of the findings of this review, i.e. that there seems to be a large body of evidence for certain PA infrastructure policies (such as sidewalks, mixed land use, or high population density). From a political science perspective, these measures should not be considered “policies.” Rather, they would be more appropriately classified as “interventions.” This, in turn, would explain why there is more evidence, as interventions lend themselves more easily to research using controlled designs.

Another recurring type of conflation in the literature is between organizational and public policy. This phenomenon is particularly pervasive in the school-setting, i.e. authors regularly fail to distinguish between rules and regulations (e.g. regarding the number of mandatory PE lessons, activity breaks, and extracurricular PA) implemented by individual schools and overarching policies by local, regional or national governments setting the regulatory context for school action. In order to properly appraise the available evidence for policy effectiveness, one should recognize that there is a fundamental difference between the actions of an individual organization and those of a public government with respect to several important factors such as reach, degree of compulsion, democratic legitimacy and use of public resources.

Further disaggregating the evidence to separate “true” policies from interventions and public from organizational policies would be extremely helpful to draw more precise conclusions about the effectiveness of PA policy and its varieties. However, we found that reviews tended to conflate public policies, organizational policies, and interventions in multiple ways and to varying degrees. Consequently, it might be necessary to re-appraise all individual studies included in each of the 57 reviews, which would be far beyond the scope of this paper and require additional research.

Finally, it is important to note that we still have very limited knowledge about the specific criteria applied by individual studies when assessing the effectiveness of individual policies. Many of the reviews we considered for this article did not report on the measures used to assess effectiveness in the underlying studies. The increase in PA levels in targeted populations may be a potentially appropriate measure to use in most contexts, but quite often, this is not possible (due to confounding factors) or feasible (due to limited resources and time-frames). In addition, PA levels in many countries have gone down consistently or stagnated over the last decades (Guthold et al., 2018), suggesting that either all policies are ineffective or that additional measures have to be employed for them to be successful (e.g. public awareness, health literacy, or amount newly developed infrastructures).

5. Conclusion

This article has presented an overview of the available evidence on the effectiveness of policies to promote PA. In doing so, it has identified a number of settings, target groups, and policy types that appear to constitute the current focus of policy evaluation in PA. It has also fostered the development of some preliminary conclusions regarding policies that can currently be recommended to promote PA (e.g. school-based and infrastructure policies) and policies for which insufficient evidence seems to exist at this point (e.g. economic instruments). Results from this review also point to a number of broader epistemological issues connected to the evaluation of PA policies, especially in relation to the question of the appropriateness of the biomedical review paradigm and the conflation of PA interventions and PA policies. The results may serve as an inspiration for both policy-makers faced with the task of choosing appropriate PA policies and for researchers intending to close gaps in the existing evidence base.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Peter Gelius, Email: peter.gelius@fau.de.

Sven Messing, Email: sven.messing@fau.de.

Lee Goodwin, Email: goodwin@ph-heidelberg.de.

Diana Schow, Email: schodian@isu.edu.

Karim Abu-Omar, Email: karim.abu-omar@fau.de.

References

- Abel T., Frohlich K.L. Capitals and capabilities: Linking structure and agency to reduce health inequalities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012;74(2):236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinroye K.K., Oyeyemi A.L., Odukoya O.O., Adeniyi A.F., Adedoyin R.A., Ojo O.S. Results from Nigeria's 2013 report card on physical activity for children and youth. J. Phys. Activity Health. 2014;11:S88–92. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government (2018). Sport 2030. Participation Performance Integrity Industry. Australia, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia as represented by the Department of Health.

- Barton H. Land use planning and health and well-being. Land Use Policy. 2009;26:S115–S123. [Google Scholar]

- Basch C.E. Healthier students are better learners: a missing link in school reforms to close the achievement gap. Equity Matters: Research Review No. 2010;6 doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basch C.E. Healthier students are better learners: a missing link in school reforms to close the achievement gap. J. School Health. 2011;81(10):593–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett D.R., Fitzhugh E.C., Heath G.W., Erwin P.C., Frederick G.M., Wolff D.L., Welch W.A., Stout A.B. Estimated energy expenditures for school-based policies and active living. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013;44(2):108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellew B., Schoeppe S., Bull F.C., Bauman A. The rise and fall of Australian physical activity policy 1996–2006: a national review framed in an international context. Aust. New Zealand Health Policy. 2008;5:18. doi: 10.1186/1743-8462-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan L.K., Brownson R.C., Orleans C.T. Childhood Obesity Policy Research and Practice: Evidence for Policy and Environmental Strategies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014;46:e1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown V., Moodie M., Carter R. Congestion pricing and active transport – evidence from five opportunities for natural experiment. J. Transp. Health. 2015;2:568–579. [Google Scholar]

- Brown V., Moodie M., Carter R. Evidence for associations between traffic calming and safety and active transport or obesity: a scoping review. J. Transport Health. 2017;7:23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Brown V., Moodie M., Cobiac L., Mantilla Herrera A.M., Carter R. Obesity-related health impacts of fuel excise taxation- an evidence review and cost-effectiveness study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:359. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4271-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson R.C., Fielding J.E., Maylahn C.M. Evidence-based public health: a fundamental concept for public health practice. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2009;30:175–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull F.C., Bellew B., Schöppe S., Bauman A.E. Developments in National Physical Activity Policy: an international review and recommendations towards better practice. J. Sci. Med. Sport/Sports Med. Australia. 2004;7:93–104. doi: 10.1016/s1440-2440(04)80283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawley J. An economy of scales: a selective review of obesity's economic causes, consequences, and solutions. J. Health Econ. 2015;43:244–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawley J. Does Anything Work to Reduce Obesity? (Yes, Modestly) J. Health Polit. Policy Law. 2016;41:463–472. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3524020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian H.E., McCormack G.R., Evenson K.R., Maitland C. Emerald Publishing Limited; 2017. Dog Walking. Walking: Connecting Substainable Transport with Health Transport and Substainability; pp. 113–135. [Google Scholar]

- Cluzeau F., Burgers J., Brouwers M., Grol R., Mäkelä M., Littlejohns P. Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the AGREE project. Quality Safety Health Care. 2003;12:18–23. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union (2013). Council Recommendation of 26 November 2013 on promoting health-enhacing physical activity across sectors. Off. J. Eur. Union, C 354/1, 1-5. Brussels, Belgium.

- de Nazelle A., Nieuwenhuijsen M.J., Anto J.M., Brauer M., Briggs D., Braun-Fahrlander C. Improving health through policies that promote active travel: a review of evidence to support integrated health impact assessment. Environ. Int. 2011;37:766–777. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Der Ananian C., Ainsworth B. Population based approaches for health promotion. Dtsch. Z. Sportmed. 2013;64:166–169. [Google Scholar]

- Després J.P., Almeras N., Gauvin L. Worksite Health and Wellness Programs: Canadian Achievements & Prospects. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014;56:484–492. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz W.H. The Response of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to the Obesity Epidemic. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2015;36:575–596. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson A.E. Graduate School of Saint Louis University; Saint Louis: 2008. Can Policy Facilitate Healthy Decision Making to Increase Physical Activity and Prevent Obesity? Philosophy. [Google Scholar]

- Echouffo-Tcheugui J.B., Kengne A.P. Chronic non-communicable diseases in Cameroon – burden, determinants and current policies. Global Health. 2011;7:44. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-7-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner G.E., Grootendorst P., Nguyen V.H., Andreyeva T., Arbour-Nicitopoulos K., Auld M.C. Economic instruments for obesity prevention: results of a scoping review and modified Delphi survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutrit. Phys. Activity. 2011;8:109. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser S.D., Lock K. Cycling for transport and public health: a systematic review of the effect of the environment on cycling. Eur. Public Health Assoc. 2011;21:738–743. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Advocacy Council for Physical Activity The Toronto charter for physical activity: a global call for action. J. Phys. Act Health. 2010;7(Suppl. 3):S370–85. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s3.s370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthold R., Stevens G.A., Riley L.M., Bull F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e1077–1086. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield D.P., Chomitz V.R. Increasing children’s physical activity during the school Day. Curr. Obesity Rep. 2015;4:147–156. doi: 10.1007/s13679-015-0159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireland Healthy. National Physical Activity Plan for Ireland; Dublin, Ireland: 2016. Get Ireland active! [Google Scholar]

- Heath G.W., Brownson R.C., Kruger J., Miles R., Powell K.E., Ramsey L.T. The effectiveness of urban design and land use and transport policies and practices to increase physical activity: a systematic review. J. Phys. Activity Health. 2006;3:S55–S76. doi: 10.1123/jpah.3.s1.s55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath G.W., Parra D.C., Sarmiento O.L., Andersen L.B., Owen N., Goenka S. Evidence-based intervention in physical activity: lessons from around the world. Lancet. 2012;380:272–281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60816-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HM Government & Mayor of London (2014). Moving More, Living More. The Physical Activity Olympic and Paralympic Legacy for the Nation. London, United Kingdom.

- Horodyska K., Luszczynska A., van den Berg M., Hendriksen M., Roos G., De Bourdeaudhuij I. Good practice characteristics of diet and physical activity interventions and policies: an umbrella review. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1354-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen T., Capewell S., Prescott E., Allender S., Sans S., Zdrojewski T. Population-level changes to promote cardiovascular health. Eur. J. Preventive Cardiol. 2012;20:409–421. doi: 10.1177/2047487312441726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knai C., Petticrew M., Scott C., Durand M.A., Eastmure E., James L. Getting England to be more physically active: are the Public Health Responsibility Deal’s physical activity pledges the answer? Int. J. Behav. Nutrit. Phys. Activity. 2015;12:107. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0264-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen A.H., Flottemesch T.J., Maciosek M.V., Jenson J., Barclay G., Ashe M. Reducing childhood obesity through U.S. Federal Policy: a microsimulation analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014;47:604–612. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika S.K., Swank M., Stachecki J., Whitt-Glover M.C., Brennan L.K. Examining the evidence for policy and environmental strategies to prevent childhood obesity in black communities: new directions and next steps. Obes. Rev. 2014;15:177–203. doi: 10.1111/obr.12206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford R., Bonell C.P., Jones H.E., Pouliou T., Murphy S.M., Waters E., Komro K.A., Gibbs L.F., Magnus D., Campbell R. The WHO health promoting school framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008958.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, P., McCullagh, M.C., Kao, T.S., Larson, J.L. (2014). An Integrative Review: Work Environment Factors Associated With Physical Activity Among White-Collar Workers. Western J. Nurs. Res., 36, 262–283. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Martin-Diener E., Kahlmeier S., Vuillemin A., van Mechelen W., Vasankari T., Racioppi F., Mart B.W. 10 years of HEPA Europe: what made it possible and what is the way into the future? Schweiz. Z. Sportmed. Sporttraumatol. 2014;62(2):6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Matson-Koffmann D.M., Brownstein J.N., Neiner J.A., Greaney M.L. A site-specific literature review of policy and environmental interventions that promote physical activity and nutrition for cardiovascular health: what works? Sci. Health Promot. 2005;19:167–193. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon R.A., Siddiqi S.M., Chaloupka F.J., Mancino L., Prasad K. Obesity-related policy/environmental interventions: a systematic review of economic analyses. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016;50:543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metos J., Murtaugh M. Words or reality: are school district wellness policies implemented? a systematic review of the literature. Childhood Obesity. 2011;7:90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mowen A.J., Baker B.L. Park, recreation, fitness, and sport sector recommendations for a more physically active AMERICA: a white paper for the United States National Physical Activity Plan. J. Phys. Activity Health. 2009;6:S236–S244. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.s2.s236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulley C., Ho C. Walking: Connecting Substainable Transport with Health Transport and Substainability. Emerald Publishing Limited; 2017. Understanding the determinants of walking as the basis for social marketing public health messaging; pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz H., David L., Katz M. American college of preventive medicine practice policy statement weight management counseling of overweight adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001;21:73–78. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuijsen M.J. Urban and transport planning, environmental exposures and health-new concepts, methods and tools to improve health in cities. Environ. Health. 2016;15(Suppl 1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12940-016-0108-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olstad D.L., Ancilotto R., Teychenne M., Minaker L.M., Taber D.R., Raine K.D. Can targeted policies reduce obesity and improve obesity-related behaviours in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations? A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2017;18:791–807. doi: 10.1111/obr.12546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen N., Glanz K., Sallis J.F., Kelder S.H. Evidence-based approaches to dissemination and diffusion of physical activity interventions. Am. J. Preventive Med. 2006;31:S35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate R.R., Trilk J.L., Byun W., Wang J. Policies to increase physical activity in children and youth. J. Exercise Sci. Fitness. 2011;9:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick K., Pratt M., Sallis R. The Healthcare Sector‘s Role in the U.S. National Physical Activity Plan. J. Phys. Activity Health. 2009;6:S211–S219. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.s2.s211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson-Wilson J., Dargavel M., Bryden P., Giles-Corti B. Physical activity policies and legislation in schools. A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012;43:643–649. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rütten A., Abu-Omar K., Gelius P., Schow D. Physical inactivity as a policy problem: applying a concept from policy analysis to a public health issue. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-11-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rütten A., Pfeifer K. FAU University Press; Erlangen: 2016. National Recommendations for Physical Activity and Physical Activity Promotion. [Google Scholar]

- Rütten A., Schow D., Breda J., Galea G., Kahlmeier S., Oppert J.-M. Three types of scientific evidence to inform physical activity policy: Results from a comparative scoping review. Int. J. Public Health. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00038-016-0807-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis J., Owen N., Fisher E. Jossey-Bass; United States: 2008. Ecological Models of Health Behaviour. Health Behaviour and Health Education, Theory, Research, and Practice. 665–482. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis J.F., Bauman A., Pratt M. Environmental and policy interventions to promote physical activity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998;15:379–397. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid T.L., Pratt M., Witmer L. A framework for physical activity policy research. J. Phys. Act Health. 2006;3:S20–S29. doi: 10.1123/jpah.3.s1.s20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sember V., Starc G., Jurak G., Golobic M., Kovac M., Samardzija P.P. Results from the republic of Slovenia’s 2016 report card on physical activity for children and youth. J. Phys. Activity Health. 2016;13:S256–S264. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2016-0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1992. Inequality Reexamined. [Google Scholar]

- Shemilt I., Hollands G.J., Marteau T.M., Nakamura R., Jebb S.A., Kelly M.P. Economic instruments for population diet and physical activity behaviour change: a systematic scoping review. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]