Abstract

Neurogenic tumors of the tracheobronchial tree are extremely rare, and these include neurofibroma and schwannoma. The rare schwannoma most frequently is reported in adults. We will report an endobronchial schwannoma in an 11-year-old boy.

Keywords: Tracheobronchial tree, Neurogenic tumors, Schwannoma, Resection, Obstructive pneumonia

1. Introduction

Schwannomas are relatively common in the mediastinum. Endobronchial location is very rare, with only scarce reports in literature. It may mislead the radiologist into a diagnosis of malignant tumor. The clinical and radiological presentations are non-specific. We present a case of endobronchial schwannoma with particular emphasis on diagnostic way.

2. History

An 11-year-old boy presented with cough persisted for about 3 months. He had recurrent bronchitis many times previously and without relevant surgical history. His cough was worse at night and post-exercise. Physical checkup revealed decreased breath sounds on the left lung. Laboratory results showed elevated inflammatory biomarkers. Imaging study included a computed tomography examination of the chest.

3. Imaging findings

CT of the chest (Fig. 1, Fig. 2) demonstrated a well-circumscribed and intraluminal nodule that nearly occluded the left main bronchus. The nodule was about 1 cm in diameter and was originated from the posterior wall at the level of the tracheal bifurcation, protruding into the left main bronchus causing obstruction and with a suspicious extra-luminal extension from the anterior outer wall of the left main bronchus without involvement of adjacent vessels. There was no calcification, cystic components and fatty tissue contained. CT without contrast revealed a soft tissue density of a CT value 30 HU and showed a moderately homogeneous enhancement with a CT value 80 HU. The associated findings included an obstructive hyperinflation of the left upper lung and pneumonia in the left lower lung.

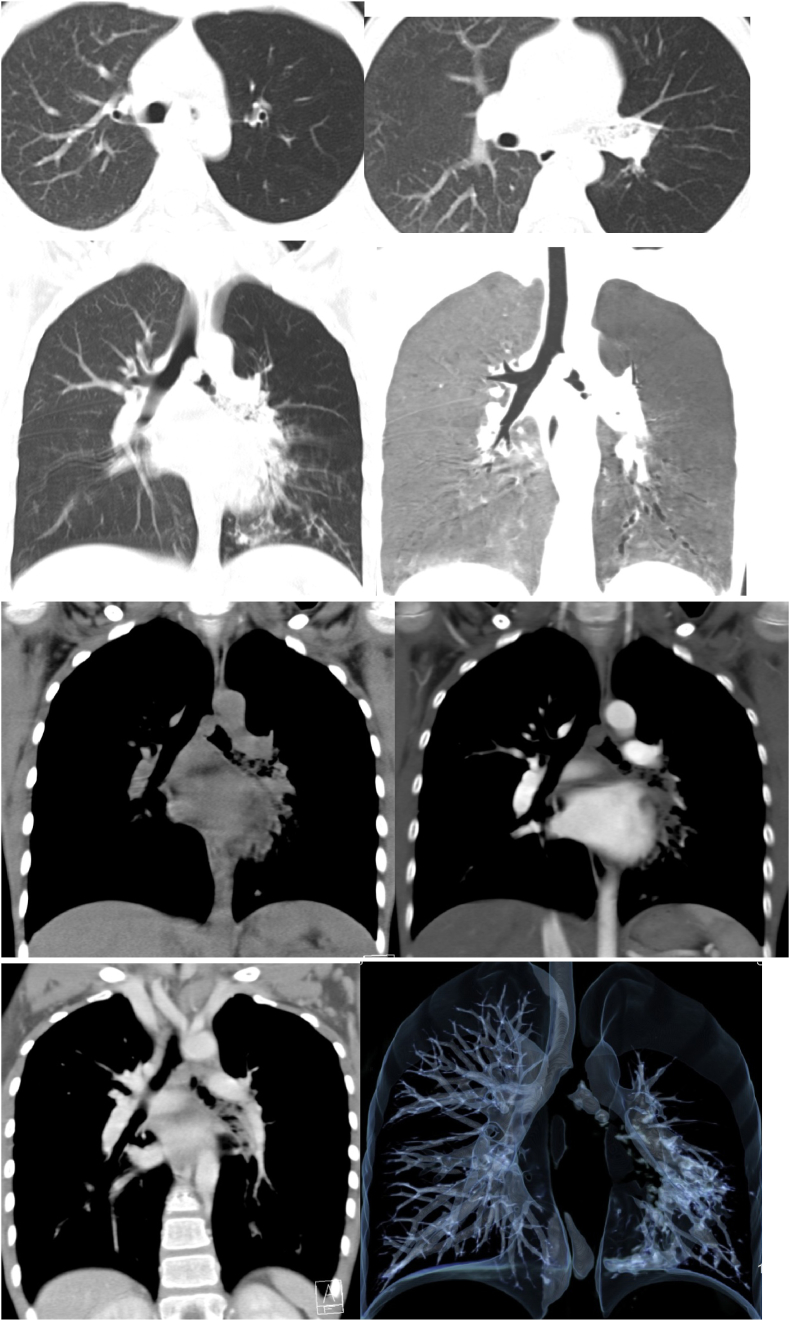

Fig. 1.

Axial CT of the chest with the lung window (a、b) and reconstructed coronal CT images with the lung window (c、d) revealed a well-demarcated intraluminal tracheal nodule with a nearly total occlusion of the left main bronchus. Note the obstructive emphysema of the left upper lung and pneumonia in the left lower lung. Reconstructed coronal CT images with the mediastinum window (e、f、g) demonstrated a hyperdense mass with a moderate homogenous contrast enhancement. 3D reconstruction CT of the tracheobronchial tree (h) indicated a defect in the left main bronchus and lesions in its branches.

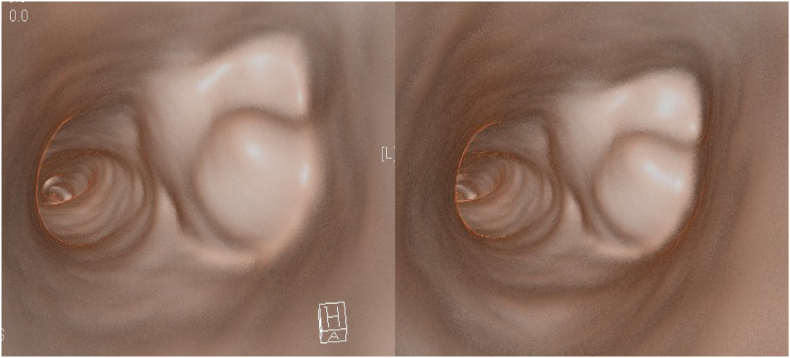

Fig. 2.

Virtual reconstruction CT of the chest demonstrated an ovoid, intraluminal mass that originated from the posterior wall of the left main bronchus.

The bronchoscopy examination revealed a smooth border tumor which occluded the lumen of left main bronchus. The mucosal surface of the tumor was covered with small superficial blood vessels. Under a bronchoscope control an endotracheal cuffed tube was inserted for the guidance of the fine needle aspiration biopsy which showed no malignant cells. To relieve the airway obstruction of the left main bronchus, the tumor was removed with electrocautery snaring under the guidance of bronchoscopy.

On histopathologic examination, the biopsy sample showed spindle cell proliferation within the subepithelial layer (Fig. 3). The spindle cells appeared bland and were arranged in a vague palisading pattern with slight myxoid background. No atypia or mitoses were identified. On immunohistochemistry, these spindle cells presented with strong and diffuse positive for S100 but were negative for smooth muscle actin. It was also positive in vimentin and CD34 (vessel) and negative for creatine kinase (CK) 、 neuron specific enolase (NSE) and desmin. The Ki67 proliferative index was about 10%+. These histologic and immunophenotypic features were consistent with schwannoma. One-week follow-up bronchoscopy and biopsy sampling results were consistent with endobronchial schwannoma.

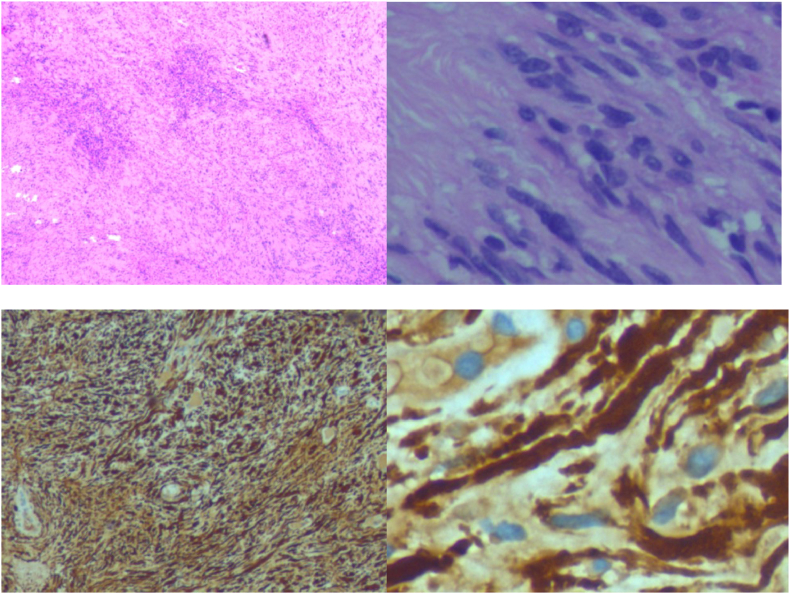

Fig. 3.

The microscopic slides illustrated a spindle cell neoplasm filled with well-differentiated Schwann cells(a、b). Immunohistochemical stain showed predominantly Antoni A and Antoni B areas, which were positive for S100 protein expression(c、d), positive in vimentin and CD34 (vessel), negative for smooth muscle actin、creatine kinase (CK) 、 neuron Specific enolase (NSE) and desmin. ki67 (10%+).

4. Outcome and follow-up

Surgery underwent without complications. The patient was evaluated 4 weeks after surgery and a chest CT was performed (Fig. 4), showing a clear left main bronchus. No clinical symptoms (such as fever, asthma and cough) were registered and there were no signs of tumor relapse.

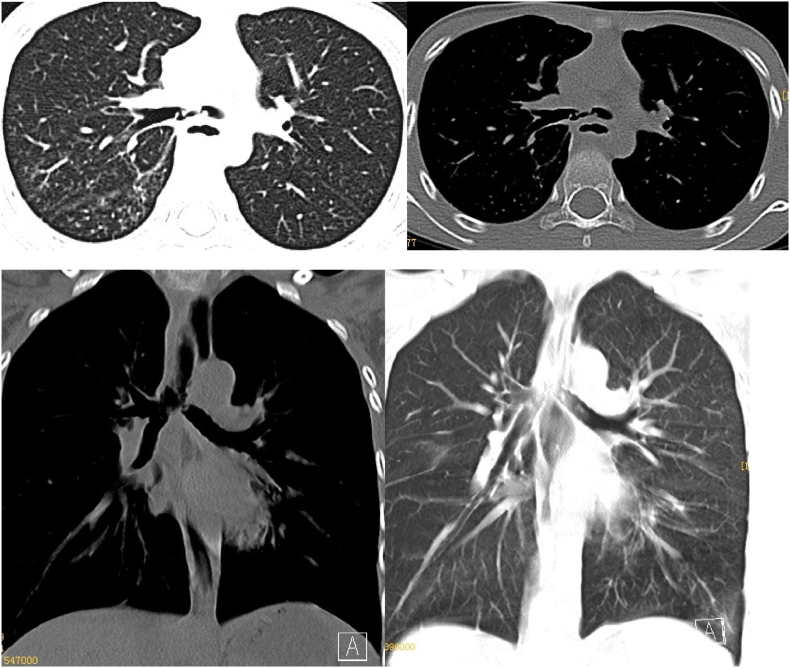

Fig. 4.

Follow-up chest CT after the operation. Axial(a、b) and reconstructed coronal(c、d) CT of the chest with the lung and mediastinum window revealed a clear left main bronchus.

5. Discussion

Primary airway tumors include a wide range of histopathologic types. In adults malignant squamous cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma account for about 75% of the tumors [1]. Primary tracheal tumors in children are rare. Unlike in adults, in children two-thirds airway tumors are benign. These benign histopathologic types [[2], [3], [4]]include hemangioma, laryngotracheal chondroma, granular cell tumor (GCT), benign fibrous tumor, and inflammatory myofibroblast tumor (IMT). Malignant tumors include carcinoid tumor (CaT), malignant fibrous tumor, and rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) [[5], [6], [7]]. Neurogenic tumors of the tracheobronchial tree are extremely rare, and these include neurofibroma and schwannoma. The rare schwannoma most frequently is reported in adults [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]]. The published literature of endobronchial schwannomas in children are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of reported bronchial schwannoma.

| Case | Age(yrs) | site | complaints | Imaging examination | Treatment management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 | endobronchial | No | pneumonectomy | |

| 2 | 10 | the left main bronchus | destruction of the pulmonary parenchyma distal to the obstruction | No | Pneumonectomy |

| 3 | 8 | the left main bronchus | destruction of the pulmonary parenchyma distal to the obstruction | no | pneumonectomy(youngest) |

| 4 | 17 | intrabronchial | left lung collapse | no | pneumonectomy |

| 5 | 18 | in the right lower lobe | persistent cough | Chest X-ray and CT | Right lower lobectomy |

| 6 | 9 | a polypoid intratracheal mass | airway obstruction | CT | Partial tracheal resection |

| 7 | 13 | right main bronchus | a 2-year history of presumed asthma not responding to bronchodilator therapy | no | resection by sleeve lobectomy |

| 8 | 9 | in the lumen of the trachea | recurrent cough, dyspnea, and tachypnea for over 3 months | chest X-ray | Endoscopic excision |

| 9 | 16 | tracheal | atypical asthma | no | a rigid bronchoscope using a CO2 laser. |

CT = Computerized Tomography.

Clinical presentation varies according to the site、size and type of the tumor [14]. Obstructive symptoms are frequently encountered, such as cough, wheezing, and dyspnea. It is common these nonspecific symptoms of airway tumors lead to misdiagnosis as bronchitis, pneumonia, or asthma episodes.

In our case, the tumor was located in the left main bronchus with a size of 1.0 cm in diameter. He had recurrent bronchitis many times previously. His cough persisted for about 3 months. We found the round nodule on his chest CT scan. However, we could not differentiate this tumor from other endobronchial tumors. The lesion without remarkable blood vessel covering and rich blood supply which essentially excluded the possibility of a hemangioma. Tracheal lipoblastoma (TL) may contain more or less fat density. Chondroma may have more frequent possibility with calcifications. Mucoepidermoid carcinomas (MC) are lobulated or oval masses with calcifications in the 50% of cases [15]; Granular cell tumors (GCT) present as ovoid soft-tissue masses [5]. CaT and IMT are characterized by lobulated and defined contours on CT scan, with calcifications less present [5].

Radiologically, the endobronchial schwannoma appears as a round, ovoid, or lobulated homogenous mass with sharp borders. A CT scan could reveal the tumor location. Chest CT may show tumor size and the extent to the lumen. It can also give the answer of whether the tumor is confined within the tracheobronchial lumen or invasion evidence to the adjacent organs. That findings may be helpful for bronchoscopic intervention or surgery.

Diagnosis of tracheobronchial schwannoma is usually made by bronchoscopy with tissue biopsy. Multislice computerized tomography is used to reveal the tumor location, size, extratracheal extension and accompanying lung signs. In the diagnostic process, the identification of the characteristics of schwannoma, including typical Antoni A formation in hematoxylin and eosin stains and S100 positivity aids in confirming the correct diagnosis of schwannoma.

In conclusion, although endobronchial schwannoma is rare, awareness of the possibility of schwannoma involving the bronchus might be helpful in making a correct diagnosis.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors had no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors are especially grateful for the support from our department that enabled us to perform the present study.

Contributor Information

Li Zhang, Email: xiaoli1103@163.com.

Wen Tang, Email: tangwen86874563@163.com.

Qing-Shan Hong, Email: ellie0103@sina.com.

Pei-feng Lv, Email: guangxiluypeifeng@163.com.

Kui-Ming Jiang, Email: kmjiang64@sina.com.

Rui Du, Email: gdsfydr@sina.com.

References

- 1.Hamouri S.1, Novotny N.M. Primary tracheal schwannoma a review of a rare entity: current understanding of management and follow up. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2017 Nov 28;12(1):105. doi: 10.1186/s13019-017-0677-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varela P., Pio L., Brandigi E. Tracheal and bronchial tumors. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016 Dec;8(12):3781–3786. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.12.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madafferi S., Catania V.D., Accinni A. Endobronchial tumor in children: unusual finding in recurrent pneumonia, report of three cases. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2015;4:30–34. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v4.i2.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yedururi S., Guillerman R.P., Chung T. Multimodality imaging of tracheobronchial disorders in children. Radiographics. 2008;28 doi: 10.1148/rg.e29. e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varela P., Pio L., Torre M. Primary tracheobronchial tumors in children. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2016 Jun;25(3):150–155. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handa A., Fujita K., Yamamoto Y. Tracheal tumor. J. Pediatr. 2016 Jun;173 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.03.017. 262-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaramillo S., Rojas Y., Slater B.J. Childhood and adolescent tracheobronchial mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC): a case-series and review of the literature. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2016;32:417–424. doi: 10.1007/s00383-015-3849-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerreiro C., Dionísio J., Duro da Costa J. Endobronchial schwannoma involving the carina. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2017 Aug;53(8):452. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2016.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isaac B.T., Christopher D.J., Thangakunam B. Tracheal schwannoma: completely resected with therapeutic bronchoscopic techniques. Lung India. 2015 May-Jun;32(3):271–273. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.156252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ge X., Han F., Guan W. Optimal treatment for primary benign intratracheal schwannoma: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015 Oct;10(4):2273–2276. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung Y.Y., Hong M.E., Han J. Bronchial schwannomas: clinicopathologic analysis of 7 cases. Kor J Pathol. 2013 Aug;47(4):326–331. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2013.47.4.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumoulin E., Gui X., Stather D.R. Endobronchial schwannoma. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2012 Jan;19(1):75–77. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0b013e318241e5aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliveira R.C., Nogueira T., Sousa V. Bronchial schwannoma: a singular lesion as a cause of obstructivepneumonia. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-217300. bcr2016217300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pio L., Varela P., Eliott M.J. Pediatric airway tumors: a report from the international network of pediatric airway teams (INPAT) Laryngoscope. 2020;130(4):E243–E251. doi: 10.1002/lary.28062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaramillo S., Rojas Y., Slater B.J. Childhood and adolescent tracheobronchial mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC): a case-series and review of the literature. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2016;32:417–424. doi: 10.1007/s00383-015-3849-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]