Summary

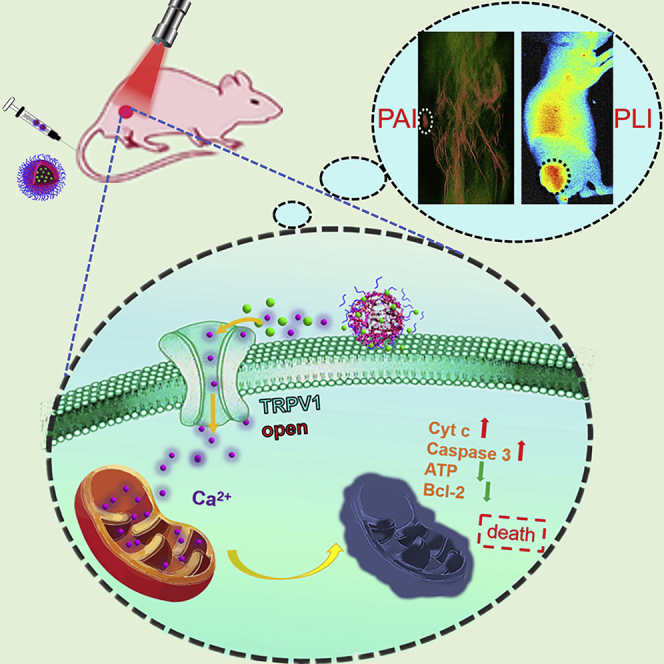

Currently, patients receiving cancer treatments routinely suffer from distressing toxic effects, most originating from premature drug leakage, poor biocompatibility, and off-targeting. For tackling this challenge, we construct an intracellular Ca2+ cascade for tumor therapy via photothermal activation of TRPV1 channels. The nanoplatform creates an artificial calcium overloading stress in specific tumor cells, which is responsible for efficient cell death. Notably, this efficient treatment is activated by mild acidity and TRPV1 channels simultaneously, which contributes to precise tumor therapy and is not limited to hypoxic tumor. In addition, Ca2+ possesses inherent unique biological effect and normal cells are more tolerant of the undesirable destructive influence than tumor cells. The Ca2+ overload leads to cell death due to mitochondrial dysfunction (upregulation of Caspase-3, cytochrome c, and downregulation of Bcl-2 and ATP), and in vivo, the released photothermal CuS nanoparticles allow an enhanced 3D photoacoustic imaging and provide instant diagnosis.

Subject Areas: Medical Imaging, Nanoparticles, Cancer

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

The Ca2+ cascade is selectively constructed in vivo without being limited to hypoxic tumor

-

•

Ca2+ overload leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and cancer death

-

•

The released CuS NPs provide an enhanced 3D photoacoustic imaging

-

•

Ca2+-interference therapy avoids the obstacles of traditional treatment

Medical Imaging; Nanoparticles; Cancer

Introduction

At present, for metastatic tumor or unresectable lesion, chemotherapy is usually the preferred option despite the emergence of many advanced treatment technologies (Nam et al., 2018, Chen et al., 2017). However, traditional chemotherapy, where the drug toxicity is always “ON,” leads to severe systemic toxicity, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, kidney problems, and neuropathic pain, which often compromises patients' quality of life (Milosavljevic et al., 2010, Wallace et al., 2010, Zhao et al., 2018). Although many smart carriers have been cunningly designed to target drug delivery to tumor sites (Cao et al., 2019, Wang et al., 2018, Dai et al., 2019), recent meta-analysis suggests that only 0.7% (median) of the administered dose is delivered to the tumor, whereas the rest is accumulated in healthy organs, which will cause some chronic diseases resulting from the toxic drugs (Wilhelm et al., 2016, Li et al., 2017). Therefore, developing a therapeutic model that can be biocompatible and keep the drug inert even if the rest accumulated in healthy organs, while it exerts its therapeutic efficacy only at the tumor site via specific transformation is necessary and also highly challenging owing to the tumor inhomogeneity.

Metal ions with diverse cellular biological effects are playing more important roles in cell metabolism and proliferation than expected (Gao et al., 2019, Zhang et al., 2019a). Any adjustment of ion balance may induce a series of intracellular reactions, even cell death (Park et al., 2019). Such a dramatic ion interference technology is expected to avoid systemic toxicity through ingenious construction. In view of this, more attention will be payed to Ca2+, as it is an essential component of tissues such as bone and is involved in a host of vital cell survival processes (Sang et al., 2018, Chen et al., 2019). Calcium overload, characterized by an abnormal accumulation of free calcium ions (Ca2+), is a widely recognized cause of damage in numerous cell types and even of cell death (Duan et al., 2019, Zhang et al., 2019b). Tumor cells are more sensitive to the persistent Ca2+ overload than normal cells (Pesakhov et al., 2016, Xu et al., 2018). In particular, transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1), a nonselective cation channel that prefers Ca2+ over other cations, has been revealed to be highly over-expressed in many malignancies (Zhen et al., 2018, Wu et al., 2014). TRPV1 can be activated by external stimuli such as heat, low pH, capsaicin, and vanilloids (Rodrigues et al., 2016). Being able to manipulate TRPV1 signaling at precise times and spaces in living systems remains a challenge.

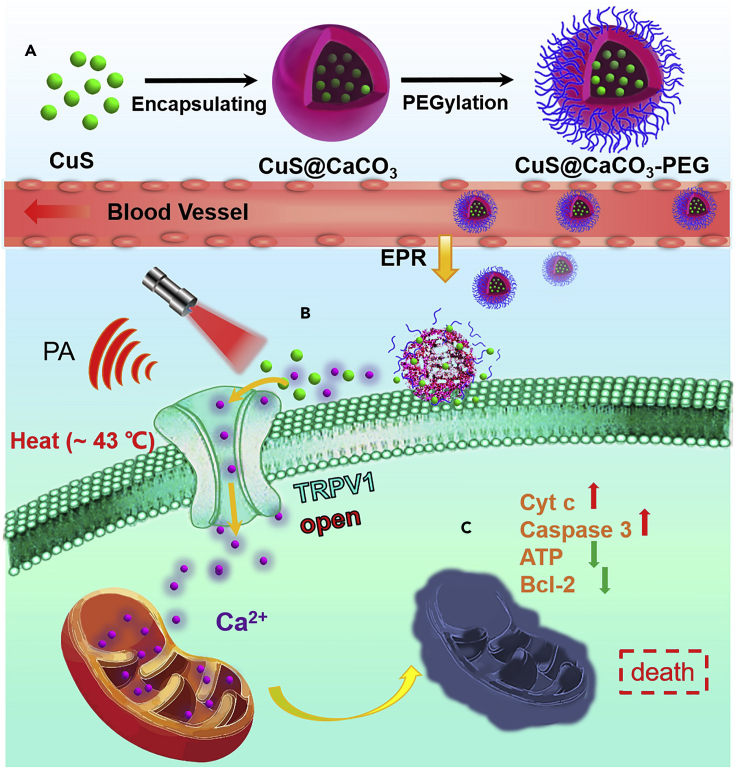

Keeping all these issues in mind, we proposed to construct a Ca2+ cascade via photothermal activation of the TRPV1 signaling pathways to specifically inhibit the growth of tumor with minimum systemic toxicity. In order to realize enhanced Ca2+ interference therapy, continuous supply of Ca2+ is essential. It is known that natural organisms CaCO3 with excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability is stable at neutral pH and can decompose in tumor acidic microenvironment, so it is mostly used as a smart carrier (Dong et al., 2018, Wan et al., 2019, Zhao et al., 2010a, Zhao et al., 2015). In addition, it could be used as a reservoir to keep the tumor supplied with plentiful Ca2+ (Li et al., 2020, Zhao et al., 2010b). Considering to activate TRPV1 signaling using near-infrared (NIR) light, we turned our attention to copper sulfide (CuS) nanoparticles (NPs) as the photothermal switch owing to the excellent photothermal efficiency (Zhou et al., 2019), photothermal combination therapy (Shao et al., 2019), and photoacoustic (PA) imaging (Zhou et al., 2020). As shown in Scheme 1, based on enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect (Kobayashi et al., 2013), the CaCO3 nanocarrier could remain and decompose at tumor site to produce abundant Ca2+ and release photothermal CuS NPs. Irradiation of CuS NPs by NIR results in strong PA signal and local heating, which contribute to guide and open TRPV1 channels allowing an influx of Ca2+. After the intracellular Ca2+ concentration rose, much larger amounts of Ca2+ could accumulate in mitochondria, leading to disrupting mitochondria Ca2+ homeostasis and dysfunction followed by cell apoptosis. However, in normal physiological environment, CaCO3 was so stable that generous Ca2+ could not be supplied, and the absence of over-expression of TRPV1 and mild acidity stimulation ensured that Ca2+ interference therapy was ineffective in normal tissues. Besides, CaCO3 was biocompatible and degradable, which ensured the worry of systemic toxicity could be completely eliminated. More meaningfully, the intracellular Ca2+ cascade for specific tumor therapy may hold promise as an effective cancer therapeutic tool complementary to traditional clinical tumor treatment.

Scheme 1.

Schematic Illustration of Calcium-Overload-Mediated Tumor Therapy by CuS@CaCO3-PEG

(A) The synthesis processes of CuS@CaCO3-PEG.

(B) The photothermal activation of the TRPV1 Ca2+ channels on the cell membrane.

(C) The mechanism of tumor cell death induced by mitochondrial damage.

Results

Preparation and Characterization of CuS@CaCO3-PEG

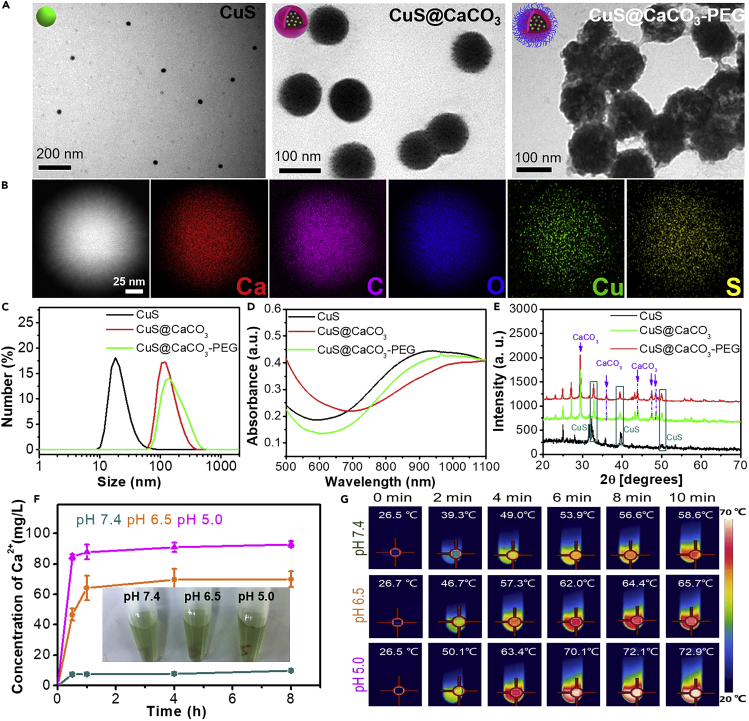

The preparation procedure of CuS@CaCO3-PEG was illustrated in Scheme 1A, and the detailed synthetic procedure was presented in the Experimental Section. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Figure 1A) showed the morphology of CuS, CuS@CaCO3, and CuS@CaCO3-PEG and as-synthesized CuS@CaCO3-PEG NPs were monodispersed with an average diameter of around 100 nm. There were some morphologically spherical pellets in the CuS@CaCO3, indicating that CuS was successfully loaded into CuS@CaCO3. The SEM image of CuS@CaCO3 was shown in Figure S1. The corresponding size distributions were shown by dynamic light scattering in Figure 1C, in accordance with TEM results. Figure S2 further demonstrated that both CuS and CuS@CaCO3 exhibited poor stability in 10% serum, whereas CuS@CaCO3-PEG had better stability both in PBS and in10% serum suggesting the improvement of in vivo application potential. Besides, the ζ potential was reversed from 13.2 to 1.6 to −10.6 mV after loading and decorating, implying the successful encapsulation and PEGylation, which avoided nonspecific adsorption in vivo. The UV-visible (UV-vis) absorption spectrum of CuS@CaCO3-PEG (Figure 1D) illustrated that there was a broad absorption between 700 and 1,100 nm, which was similar to the absorption of CuS NPs. X-ray diffraction results evidenced the presence of CuS NPs and CaCO3 in the NPs. After PEGylation, the decrease of the peak intensity was due to the cover of phospholipid bilayer on the surface (Figure 1E). To substantially confirm the successful loading of CuS NPs in CaCO3, energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) mapping was conducted. As shown in Figure 1B, S and Cu elements were evenly dispersed in CuS@CaCO3, which indicated that CuS was successfully encapsulated in CaCO3.

Figure 1.

Characterization of the Nanoplatform

(A and B) (A) TEM pictures of CuS, CuS@CaCO3, and CuS@CaCO3-PEG. (B) TEM elemental mapping of CuS@CaCO3.

(C–E) (C) Dynamic light scattering (see also Figure S2, D) Ultraviolet-visible absorption spectrum and (E) X-ray diffraction of CuS, CuS@CaCO3, and CuS@CaCO3-PEG.

(F) The effect of pH on release of Ca2+ from CuS@CaCO3-PEG (inset: pictures of centrifugated CuS@CaCO3-PEG at different pH for 1 h, n = 3) (see also Figures S4 and S5). Data are represented as mean ± SD.

(G) Thermal images of CuS@CaCO3-PEG at different pH with irradiation by 1,064-nm laser (1.2 W cm−2) for 10 min (see also Figures S6 and S7).

Acid Enhanced Ca2+ Release and Photothermal Effect of CuS@CaCO3-PEG

Owing to the successful loading of CuS NPs in CaCO3, CuS@CaCO3-PEG may disintegrate and release Ca2+ and CuS at low pH. First, the collapse of CuS@CaCO3-PEG treated with different pH PBS was observed via TEM. As shown in Figure S4, with an increase of acidity, the CuS@CaCO3-PEG NPs were gradually destroyed. At pH 7.4, all of them kept intact, indicating CuS@CaCO3-PEG could remain stable in physiological environments. In particular, almost all of them disintegrated into smaller particles at pH 5.0. At the same time, the light transmittance of CuS@CaCO3-PEG treated with different pH was shown in Figure 1F insert, and the light transmittance gradually increased with the decrease of pH, which reveals the pH-responsive decomposition of CuS@CaCO3-PEG. After centrifugation and supernatant collection, the concentrations of Ca2+ and Cu2+ were, respectively, measured via inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). As shown in Figure 1F, after interaction for 30 min, the concentration of Ca2+ rose to 82 mg L−1 with decrease of solution pH, suggesting that the production of abundant Ca2+ was effective in tumor microenvironment. With disintegration of CuS@CaCO3-PEG at lower pH, more CuS NPs will be released in the acid environment. As shown in Figure S5, less than 30% of Cu2+ is released after 8 h of treatment at pH 7.4, suggesting the CaCO3 is a desired gatekeeper. On the contrary, within 1 h, the release of Cu2+ reached 66% and 52% at pH 5.0 and 6.5, respectively. All these results substantially demonstrated that CuS@CaCO3-PEG could reactively decompose at low pH and rapidly release abundant Ca2+ and loaded CuS NPs.

The photothermal properties of CuS@CaCO3-PEG were studied because of the influential NIR absorption band. Owing to a tumor acidic environment, we further evaluated the photothermal effect of CuS@CaCO3-PEG at pH 6.5 and 5.0. As displayed in Figure 1G, the solution temperature quickly increased with prolonging of irradiation time. Notably, the lower the pH was, the faster and higher the temperature rose. It may be attributed to the release of CuS from the cracking of calcium carbonate, which had a stronger absorbance in NIR. The photothermal property of CuS@CaCO3-PEG was also concentration and power dependent (Figure S6). Besides, CuS@CaCO3-PEG showed excellent thermal stability in PBS (Figure S7).

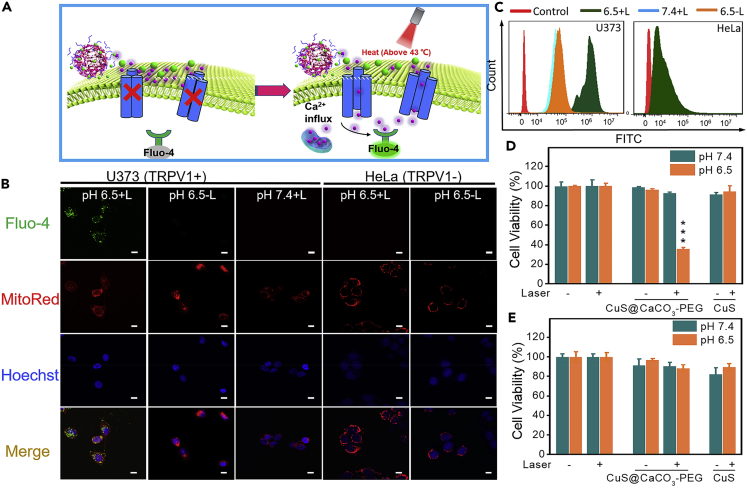

Ca2+ Influx In Vitro by NIR-II Laser Irradiation

Considering that CuS@CaCO3-PEG can produce abundant Ca2+ and has excellent photothermal conversion characteristic in tumor acidic environment, the ability of CuS@CaCO3-PEG to activate heat-sensitive TRPV1 Ca2+ channels was examined in two different cells. The U373 glioma cells are the experimental group, which provided a high expression of TRPV1 pathway, whereas HeLa cells are the TRPV1-negative cells (Lyu et al., 2016, Amantini et al., 2007). First, the intracellular Ca2+ influx was monitored by Ca2+ fluorescence probe (Fluo-4) (Figure 2A). Under laser irradiation at 1,064 nm (1.2 W cm−2) for 30 s, no fluorescence increase was observed in pH 7.4 + L group or pH 6.5 - L group of TRPV1-positive cells; in contrast, significant fluorescence increase was detected for S pH 6.5 + L group (Figure 2B). Therefore, Ca2+ influx was activated for U373 cells only when both acidic environment and NIR irradiation were satisfied, ensuring the high precision of CuS@CaCO3-PEG to tumor cells. However, no fluorescence of Fluo-4 was observed in the TRPV1-negative cells (HeLa) even when the above conditions existed, validating that Ca2+ influx was specifically activated by PTT-induced TRPV1 opening. The quantitative fluorescence intensity of Fluo-4 was detected by flow cytometry in Figure 2C. The fluorescence intensity in U373 cells of pH 6.5 + L group was a high level when compared with the blank control group. In other groups, there was no significant fluorescence enhancement, which was consistent with the results of CLSM, showing weak fluorescence of Fluo-4. In order to further verify that heat can induce the opening of calcium channels, the two kinds of cells treated with CuS@CaCO3-PEG were incubated in 43°C incubator for 10 min and the fluorescence of Fluo-4 was detected by CLSM. As shown in Figure S8, obvious fluorescence of Fluo-4 was displayed in the mitochondria of U373 cells but not in HeLa cells. This demonstrated that it was indeed heat-induced calcium ion influx in our work.

Figure 2.

In Vitro Activation of TRPV1 Ion Channels by NIR-II (1,064 nm) Laser Irradiation

(A) Schematic illustration of photothermal mechanism of activation of TRPV-1 Ca2+ channels in cells. The intracellular concentration of Ca2+ was monitored in real time by using Fluo-4 as the indicator, which turned on its fluorescence upon binding with Ca2+.

(B) CLSM images and colocation ratio analysis of biodistribution of Ca2+ released from CuS@CaCO3-PEG in mitochondria after treatment with CuS@CaCO3-PEG in U373 and HeLa cells after 1,064-nm laser irradiation (1.2 W cm−2) (see also Figure S8); scale bar: 10 μm.

(C–E) (C) Quantitative determination of intracellular (U373 and HeLa cells) Ca2+ by flow cytometry. The cytotoxicity of CuS@CaCO3-PEG against U373 (D) and HeLa (E) cells in the presence or absence of 1,064-nm laser irradiation (see also Figures S9–S12). ∗∗∗p < 0.001, compared with the control group. Data are represented as mean ± SD.

When intracellular Ca2+ concentrations rise, rapid mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in living cells was shown (Thor et al., 1984). Because when temporary imbalance of intracellular Ca2+ occurs, mitochondria as sensors and regulators will take in Ca2+ from the cytoplasm to regulate intracellular calcium homeostasis (Rizzuto et al., 2012). Inspired by this, the colocalization of intracellular Ca2+ and mitochondria was then observed through CLSM, where mitochondria were marked by MitoRed indicator. Most of Ca2+ was well co-localized with mitochondria, which revealed that abundant Ca2+ finally arrived at mitochondria after flowing into the cells through TRPV1 channels.

Selective Toxic Activation of CuS@CaCO3-PEG

Mitochondria regulate intracellular calcium homeostasis (Williams et al., 2013); however, excessive Ca2+ in mitochondria triggers cell apoptosis (Giorgi et al., 2012). The calcium overload toxicity assays of CuS@CaCO3-PEG were executed for U373 cells and HeLa cells. As shown in Figure 2D, CuS@CaCO3-PEG would not initiate U373 cells death at pH 7.4 with/without light irradiation, and even when the concentration of Ca2+ was increased without light irradiation (Figure S9), suggesting the good biocompatibility of CuS@CaCO3-PEG under typical physiological pH environment. To evaluate the selective toxicity of CuS@CaCO3-PEG, the toxicities of CuS@CaCO3-PEG on normal cells (COS7 cells) and TRPV1-positive tumor cell lines (HEK293 cells) (Sanz-Salvador et al., 2012) were tested by MTT. As shown in Figure S10, the CuS@CaCO3-PEG had no toxicity to normal cells, whereas it had obvious toxicity to TRPV1-positive cells (HEK 293 cells), which further confirmed the nanoplatform for specifically inhibiting cancer. When cells were cultured at pH 6.5 without irradiation, cells exhibited good survival, implying that the Ca2+ influx induced by endocytosis was not enough to induce cell death maybe due to its own mechanism of calcium regulation. Meanwhile, CuS exhibited little phototoxicity in the cell experiment, because the temperature of culture medium was strictly detected and controlled at around 43°C by thermal camera (Figure S11), in order to avoid the cell death caused by hyperthermia. In sharp contrast, CuS@CaCO3-PEG displayed apparent toxicity in U373 cells at pH 6.5 with laser irradiation. Combined with the results of Ca2+ influx and MTT, it was proved that Ca2+ overload in mitochondria could finally lead to cell death. However, there existed no toxicity in HeLa cell experiments (Figure 2E), which powerfully confirmed that selective cancer cell death caused by calcium overload was indeed guided by activation of TRPV1. In addition, the two kinds of cells treated with CuS@CaCO3-PEG were cultured in 43°C incubator for 10 min, and the same phenomenon of cell viability appeared. There existed obvious toxicity only in pH 6.5 group of U373 cells (Figure S12). All these results substantially indicated that CuS@CaCO3-PEG could selectively kill U373 cells (TRPV1+), because the opening of TRPV1 channels by heat was the fuse of calcium overload, which led to subsequent cell death.

To investigate the cell death pathway by calcium overload, cells were incubated with CuS@CaCO3-PEG in the presence or absence of light irradiation under different pH environment, and then cells were labeled with annexin VFITC/PI. Early apoptosis can be detected using annexin V by combining with the exposed phosphatidylserine on the cell surface, whereas PI can stain nuclear chromatin rapidly in membrane-compromised cells during late apoptosis or necrosis (Liang et al., 2018). As shown in Figure S13, cells treated with CuS@CaCO3-PEG at pH 6.5 with light irradiation exhibited the highest late apoptotic and the necrosis ratio of 20.17% compared with other groups. This was in good agreement with the published report that disruption of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis will result in an increased rate of cell necrosis (Orrenius et al., 2003, Scorrano et al., 2003).

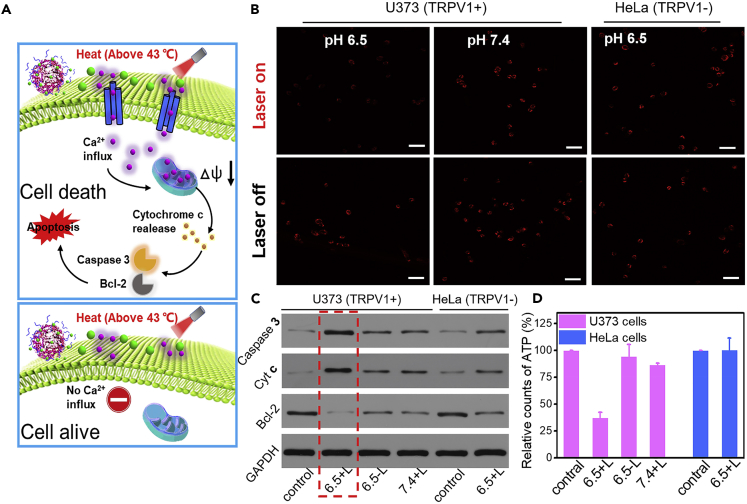

Disruption of Mitochondrial Ca2+ Homeostasis of CuS@CaCO3-PEG

Proposed apoptosis mechanism induced by CuS@CaCO3-PEG was illustrated in Figure 3A. For further investigating the mechanism of apoptosis of calcium overload in mitochondria, mitochondrial dysfunction resulting from disruption of mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis was studied by tetramethyl rhodamine dye (TMRM) staining, because the decrease in fluorescence of TMRM reflects an increase in the degree of depolarization of the membrane potential (Ma et al., 2018). As shown in Figure 3B, there was bright red fluorescence of TMRM when U373 cells treated with CuS@CaCO3-PEG were at pH 7.4 with light irradiation, suggesting that a little Ca2+ flowing through TRPV1 channels would not damage the mitochondria. When U373 cells treated with CuS@CaCO3-PEG were at pH 6.5 without light irradiation, the fluorescence changed little, indicating that the cell itself could maintain Ca2+ homeostasis and protect mitochondria, unless a specific regulating pathway was destroyed (Rizzuto and Pozzan, 2006). However, in pH 6.5 + L group of U373 cells, the red fluorescence dramatically decreased. This great difference suggested that Ca2+ overload in mitochondria by opening the TRPV1 channels seriously harassed the membrane potential of mitochondria in U373 cells (TRPV1+). In contrast, there was no difference in fluorescence intensity between pH 6.5 with and without light in HeLa cells. Simultaneously, the quantitative results of fluorescence intensity were further determined via flow cytometry in Figure S14. When compared with other groups, significant decrease of the fluorescence intensity of TMRM was observed in pH 6.5 + L group of U373 cells, in accordance with CLSM results. Once the mitochondria were damaged, there was the influx of various regulatory proteins including cytochrome c (Cyt c) and caspase-3 proteins into the cytoplasm (Li et al., 2019) and the decrease of antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 (Tian et al., 2019). To confirm this, the applications of western blotting (WB) techniques were executed to study the expression of these proteins. As shown in Figure 3C, the protein levels of caspase-3 and cytochrome c were elevated when U373 cells treated by CuS@CaCO3-PEG were at pH 6.5 with light irradiation, whereas the protein levels in other groups were reduced. Besides, only when U373 cells were treated by CuS@CaCO3-PEG in pH 6.5 + L group, the expressions of Bcl-2 protein were significantly down-regulated. Detailed quantitative results of WB were gathered in Figure S15. Because mitochondria are the energy house, the damage of mitochondrial function might directly affect the production of ATP (Zhen et al., 2019). As shown in Figure 3D, the ATP content of U373 cells in 6.5 + L group decreased significantly compared with that of other groups, indicating that Ca2+ overload in mitochondria would damage the energy supply of cancer cells. All of the results revealed that mitochondrial-mediated apoptotic pathway was activated, after the mitochondrial calcium ion was overloaded.

Figure 3.

The Mechanism of Mitochondrial Damage Mediated by Calcium Overload In Vitro

(A) Schematic illustration of proposed apoptosis mechanism induced by CuS@CaCO3-PEG.

(B) Membrane depolarization of mitochondria when U373 and HeLa cells were treated with CuS@CaCO3-PEG under different pH in the presence or absence of light irradiation. Mitochondria were labeled with TMRM (see also Figure S14); scale bar: 50 μm.

(C) Western blotting analysis of caspase-3, Cyt c, and Bcl-2 (see also Figure S15).

(D) Intracellular (U373 and HeLa cells) ATP content analysis under the same environment above (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SD.

Multimodal Imaging of Tumor

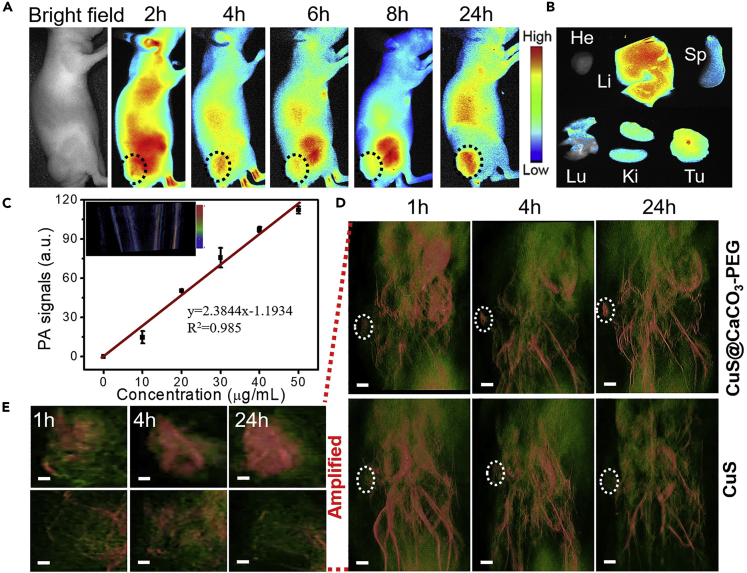

The therapeutic capability in vivo of CuS@CaCO3-PEG NPs was evaluated on HepG2 (liver hepatocellular cells) xenograft tumor mouse models, but not on the U373 tumor-bearing mouse models, since U373 cells grew too slowly, which made it challenging to establish tumor-bearing mouse models, whereas HepG2 tumor-bearing mouse models were easy to establish and also possessed high expression of TRPV1 pathway (Waning et al., 2007, Vriens et al., 2004, Bort et al., 2019). Also, liver cancer is one of the most common and lethal cancers in the human digestive system. Prior to in vivo therapy, the biodistribution of the nanomedicine was tracked by Cy7 via fluorescence imaging in vivo. As shown in Figure 4A, the fluorescence gradually appeared in the tumor site over time. After 4 h of injection, more fluorescence signal of Cy7 was observed in the tumor than at other time points, so in the following in vivo antitumor activity studies, the NIR laser irradiation time was set at 4 h after injection. At 24 h post injection of Cy7-labeled CuS@CaCO3-PEG, mice were killed and their tumors and organs were exfoliated for ex vivo imaging. As shown in Figure 4, except for the liver, tumor had the most robust fluorescence, since liver is the main metabolic organ, leading to the nonspecific liver uptake. The biodistribution of Cy7-labeled CuS@CaCO3-PEG revealed that CuS@CaCO3-PEG could significantly accumulate in the tumor site via enhanced penetration and retention effect. Furthermore, the photoacoustic imaging of CuS@CaCO3-PEG was explored in vitro and in vivo. First, the linear relationship between the concentrations and the mean photoacoustic signals (R2 = 0.985) was shown in Figure 4C, which indicated that the CuS@CaCO3-PEG was an effective photoacoustic contrast agent for diagnosis. Thus, the in vivo PAI performance of CuS@CaCO3-PEG was further evaluated compared with CuS in HepG2 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice. The 3D high-resolution PAI of the whole mice were recorded in a time-dependent method after intravenous injection (Figures 4D and 4E). In the free CuS group, after injection of CuS for 1 h, the PA signal was little in the tumor, whereas the partial signal was in the tumor and kidney at 4 h, indicating that CuS NPs were cleared by the body after injection for 4 h. After injection for 24 h, there were few fluorescence signals in the tumor. Meanwhile, in the CuS@CaCO3-PEG group, after injection for 1 h, the PA signal of CuS@CaCO3-PEG was stronger compared with that of free CuS, whereas an obvious PA signal occurred in the tumor site at 4 h, and still was at a high level in tumor at 24 h. Comparisons showed that CuS@CaCO3-PEG had better tumor accumulation and 3D diagnosis than small size CuS in the blood circulation, which would contribute to the subsequent Ca2+-mediated therapy guided by 3D PA diagnosis.

Figure 4.

In Vivo Fluorescence and Three-Dimensional PA Imaging

(A) Biodistribution images of Cy7-loaded CuS@CaCO3-PEG nanoparticles in HepG2 tumor-bearing mice at preset times after intravenous injection. The black circles pointed the tumor tissue.

(B) Ex vivo fluorescence images of various organs and tumor tissue at 24 h after injection.

(C) In vitro PA imaging of different concentrations of CuS@CaCO3-PEG under 1,064-nm laser irradiation. Data are represented as mean ± SD.

(D) In vivo three-dimensional PA imaging of the tumor-bearing mice intravenous injection with CuS@CaCO3-PEG and CuS under 1,064-nm laser irradiation at different times. The white circles pointed the tumor tissue. Scale bar: 6 mm.

(E) The amplified PA imaging pictures of the local tumors in Figure 4D. Scale bar: 1 mm.

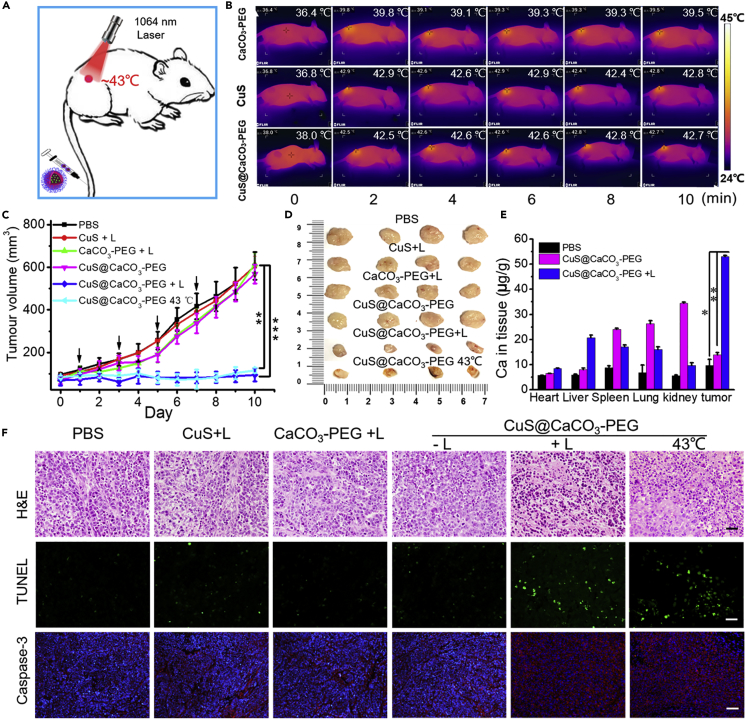

Ca2+-Mediated Tumor Therapy In Vivo

Subsequently, the in vivo Ca2+-interference therapy was conducted, as shown in Figure 5A. The HepG2 tumor-bearing female BALB/c nude mice were randomly divided into six groups for the different treatments: (1) PBS, (2) CuS +1,064 nm light irradiation, (3) CaCO3-PEG + 1,064 nm light irradiation, (4) CuS@CaCO3-PEG, (5) CuS@CaCO3-PEG + 1,064 nm light irradiation, and (6) CuS@CaCO3-PEG 43°C. After 4 h injection, the irradiation was performed, and the laser irradiation time was controlled to be 10 min in an intermittent manner (30 s break after 30 s of irradiation) so that the temperature of tumor areas was controlled below 43°C by FLIR infrared camera (Figure 5B), which was favorable to open the TRPV1 channels while avoiding the burn of tumors by hyperthermia. As shown in Figure 5C, evident inhibition of tumors was observed in group 5 (CuS@CaCO3-PEG with light exposure) and group 6 (CuS@CaCO3-PEG 43°C). However, there was no therapeutic effect in other groups compared with the PBS group. During treatment, there was no change in body weight in the six groups (Figure S16A), suggesting the negligible side effect. After 10 days treatment, it was found that the harvested tumor displayed the lowest values in size and weight in group 5 and group 6 than those in the other groups (Figures 5D and S16B), suggesting that the nanoplatform had specific therapeutic effect in vivo. The blood circulation half-lives of CuS@CaCO3-PEG (3.0 h) could reach about 2-fold that of CuS@CaCO3 (1.6 h) and 4-fold that of the bare CuS (0.8 h) by ICP-MS in Figure S17, revealing that CuS@CaCO3-PEG exhibited enhanced blood circulation after PEGylation in vivo. To check whether a large amount of Ca2+ accumulated in the tumors, organs and tumors of mice in those groups were collected, digested, and then examined by ICP-MS. As shown in Figure 5E, it could be found that, after treatment by CuS@CaCO3-PEG with light irradiation, the Ca2+ content in tumors significantly increased compared with that of the control groups, confirming abundant Ca2+ production and retention in tumors from CuS@CaCO3-PEG after light irradiation. Yet, Ca2+ in the control groups were mainly concentrated in spleen, lung, and kidney, since these are the main metabolic organs (Wu and Tang, 2018). The desired therapeutic effects were also confirmed by physiological pathological staining in Figure 5F. For H&E staining, a small portion of purple-blue (normal nucleus) and large amounts of deformed nuclei (karyopyknosis, separation, and fragmentation) in tumor tissues were observed in the CuS@CaCO3-PEG + Laser and CuS@CaCO3-PEG 43°C groups. From the TUNEL staining, representative apoptosis-positive cells were marked by green nuclei in the last two groups. Simultaneously, there were large numbers apoptotic cells in caspase-3 staining assay. On the contrary, there were no significant physiological morphology changes in the staining of tumor tissue sections in other groups as compared with results in PBS group. Altogether, the photothermally induced opening of TRPV1 channels led to the overload of Ca2+ in tumor, which effectively realized Ca2+-interference therapy and damaging against tumor survival in vivo.

Figure 5.

In Vivo Calcium-Overload-Mediated Tumor Therapy

(A) Schematic illustration of CuS@CaCO3-PEG-based photothermal activation of calcium influx inhibits tumor growth.

(B) IR thermal images of tumor-bearing mice under 1,064-nm laser irradiation to control temperature after systemic administration of CaCO3-PEG, CuS, and CuS@CaCO3-PEG at post-injection time of 4 h.

(C and D) (C) Tumor volume change and (D) photos of the tumors extracted from mice in different groups after treatment (see also Figure S16).

(E) Biodistribution of Ca2+ content in various organs and tumor after 1,064-nm laser irradiation (1.2 W cm−2) for 10 min at 4 h intravenous injection of CuS@CaCO3-PEG, the Ca2+ content was detected by ICP-MS.

(F) H&E, TUNEL, and cleaved caspase-3 staining of tumor tissues exfoliated from different groups. Scale bar: 50 μm. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, compared with the indicated group. Data are represented as mean ± SD.

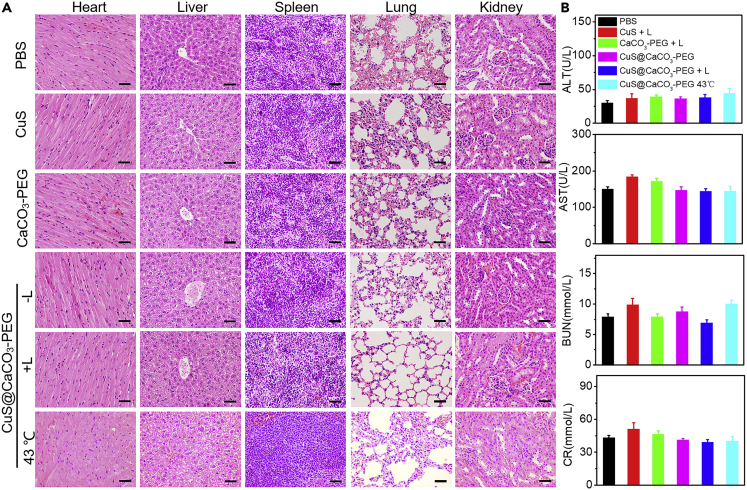

Neglectable systemic toxicity should also be taken into account when effective cancer treatment was carried out. So, the minimal systemic toxicity had also been demonstrated to analyze the physiological pathology of major organs by H&E staining. Compared with the results of PBS, there were no physiological morphology changes in heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney in Figure 6A, suggesting biosafety of the nanoplatform in vivo. In addition, potential toxicity had been studied through liver function markers glutamic pyruvate transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and kidney function markers blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine (CR) in serum in Figure 6B. These results suggested that there were no dysfunctions of liver and kidney in the treatment of CuS@CaCO3-PEG in vivo. Thus, it can be concluded that the Ca2+-interference therapy induced by photothermal activation of a TRPV1 signaling pathway to specifically inhibit tumor had negligible biotoxicity, owing to its excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability. More importantly, there were no toxic drugs in the whole treatment, which may cause the worry of systemic toxicity.

Figure 6.

Systemic Toxicity Evaluation of the Nanoplatform

(A) H&E staining of lung, liver, spleen, heart, and kidneys exfoliated from different groups. “L” represents that the 1,064-nm laser irradiation was to maintain the temperature of tumor at about 43°C for 10 min. Scale bar: 50 μm.

(B) ALT, AST, BUN, and CR in serum were detected in various samples. Data are represented as mean ± SD.

Discussion

We developed an intracellular Ca2+ cascade that can be induced by photothermal activation of a TRPV1 signaling pathway to specifically inhibit tumor without any worry of systemic toxicity. CuS@CaCO3-PEG could specifically construct Ca2+ cascades in the presence of the overexpress TRPV1 channels and NIR-II light irradiation at tumor sites. Subsequently, the overflowing Ca2+ caused disruption of mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis and dysfunction, leading to efficient tumor inhibition. In addition, released photothermal CuS NPs could be used as an enhanced photoacoustic (PA) imaging agent simultaneously to provide instant diagnostic functions. More importantly, the Ca2+-interference therapy demonstrated here avoided the obstacles of cancer treatments, i.e., premature drug leakage, off-targeting, and poor biocompatibility, which lightens the availability of other metal ions in oncotherapy and opens a new door for further higher-quality clinical cancer treatment.

Limitations of the Study

Even though we performed a Ca2+ cascade by NIR-II photothermal switch for specific tumor therapy in vitro and in vivo, we did not study the threshold of Ca2+ concentration in Ca2+-interference therapy. Single calcium overload showed obvious antitumor effect; whether the nanoplatform combined with other treatments possessing the desired effect of “1 + 1 > 2” needs further investigation.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the financial support by National Natural Science Foundation of China (21778020, 31750110464 and 31950410755), Sci-tech Innovation Foundation of Huazhong Agricultural University (2662017PY042 and 2662018PY024), National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFD0500706) and Science and Technology Major Project of Guangxi (Gui Ke AA18118046). We thank The Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhongshan University and Wuhan Institute of Virology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for our 3D PA imaging and in vivo fluorescence imaging work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.M.; Methodology, Z.M., J.Z., and W.Z.; Investigation, Z.M., J.Z., W.Z., Y.Z., and L.G.; Writing – Original Draft, Z.M.; Writing – Review & Editing, Z.M., M.F.F. and H.H.; Supervision, H.H.; Funding Acquisition, M.F.F. and H.H.. All authors edited and agreed on the final version.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: May 22, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101049.

Supplemental Information

References

- Amantini C., Mosca M., Nabissi M., Lucciarini R., Caprodossi S., Arcella A., Giangaspero F., Santoni G. Capsaicin-induced apoptosis of glioma cells is mediated by TRPV1 vanilloid receptor and requires p38 MAPK activation. J. Neurochem. 2007;102:977–990. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bort A., Sánchez B.G., Mateos-Gómez P.A., Díaz-Laviada I., Rodríguez-Henche N. Capsaicin targets lipogenesis in HepG2 cells through AMPK activation, AKT inhibition and PPARs regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:1660–1677. doi: 10.3390/ijms20071660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M.W., Lu S., Wang N.N., Xu H., Cox H., Li R.H., Waigh T., Han Y.C., Wang Y.L., Lu J.R. Enzyme-triggered morphological transition of peptide nanostructures for tumor-targeted drug delivery and enhanced cancer therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:16357–16366. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b03519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.J., Ding J.X., Xu W.G., Sun T.M., Xiao H.H., Zhang X.L., Chen X.S. Receptor and microenvironment dual-recognizable nanogel for targeted chemotherapy of highly metastatic malignancy. Nano Lett. 2017;17:4526–4533. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b02129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q.S., Huo D., Cheng H.Y., Lyu Z.H., Zhu C.L., Guan B.H., Xia Y.N. Near-infrared-Triggered release of Ca2+ ions for potential application in combination cancer therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019;8:1801113–1801120. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201801113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai L.L., Li X., Duan X.L., Li M.H., Niu P.Y., Xu H.Y., Cai K.Y., Yang H. A pH/ROS Cascade-responsive charge-reversal Nanosystem with self-amplified drug release for synergistic oxidation-chemotherapy. Adv. Sci. 2019;6:1801807–1801819. doi: 10.1002/advs.201801807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z.L., Feng L.Z., Hao Y., Chen M.C., Gao M., Chao Y., Zhao H., Zhu W.W., Liu J.J., Liang C. Synthesis of hollow biomineralized CaCO3–polydopamine nanoparticles for multimodal imaging-guided cancer photodynamic therapy with reduced skin photosensitivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:2165–2178. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b11036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J.X., Navarro-Dorado J., Clark J.H., Kinnear N.P., Meinke P., Schirmer E.C., Evans A.M. The cell-wide web coordinates cellular processes by directing site-specific Ca2+ flux across cytoplasmic nanocourses. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2299–2310. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10055-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao R., Xu L.G., Hao C.L., Xu C.L., Kuang H. Circular polarized light activated chiral satellite nanoprobes for the imaging and analysis of multiple metal ions in living cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;131:3953–3957. doi: 10.1002/anie.201814282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi C., Baldassari F., Bononi A., Bonora M., Marchi E. De, Marchi S., Missiroli S., Patergnani S., Rimessi A., Suski J. Mitochondrial Ca2+ and apoptosis. Cell Calcium. 2012;52:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H., Watanabe R., Choyke P.L. Improving conventional enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effects; what is the appropriate target. Theranostics. 2013;4:81–89. doi: 10.7150/thno.7193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.H., Chen Y.Y., Pan W., Yu Z.Z., Yang L.M., Wang H.Y., Li N., Tang B. Nanocarriers with multi-locked DNA valves targeting intracellular tumor-related mRNAs for controlled drug release. Nanoscale. 2017;9:17318–17324. doi: 10.1039/c7nr06479a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.J., Dang J.J., Liang Q.J., Yin L.C. Thermal-responsive carbon monoxide (CO) delivery expedites metabolic exhaustion of cancer cells toward reversal of chemotherapy resistance. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019;5:1044–1058. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.R., Zhang X.Y., Lin X.L., Zhuang X.Q., Wu Y., Liu Z., Rong J.H., Zhao J.H. CaCO3 nanoparticles pH-sensitively induce blood coagulation as a potential strategy for starving tumor therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2020;8:1223–1234. doi: 10.1039/c9tb02684c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang R.J., Chen Y., Huo M.F., Zhang J., Li Y.S. Sequential catalytic nanomedicine augments synergistic chemodrug and chemodynamic cancer therapy. Nanoscale Horiz. 2018;4:890–901. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu Y., Xie C., Chechetka S.A., Miyako E., Pu K.Y. Semiconducting polymer nanobioconjugates for targeted photothermal activation of neurons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:9049–9052. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b05192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z.Y., Han K., Dai X.X., Han H.Y. Precisely striking tumors without adjacent normal tissue damage via mitochondria-templated accumulation. ACS Nano. 2018;12:6252–6262. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b03212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milosavljevic N., Duranton C., Djerbi N., Puech P.H., Gounon P., Lagadic-Gossmann D., Dimanche-Boitrel M.T., Rauch C., Tauc M., Counillon L., Poet M. Nongenomic effects of cisplatin: acute inhibition of mechanosensitive transporters and channels without actin remodeling. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7514–7522. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam J., Son S., Ochyl L.J., Kuai R., Schwendeman A., Moon J.J. Chemo-photothermal therapy combination elicits anti-tumor immunity against advanced metastatic cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1074–1086. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03473-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrenius S., Zhivotovsky B., Nicotera P. Regulation of cell death: the calcium–apoptosis link. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:552–565. doi: 10.1038/nrm1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.H., Park S.H., Howe E.N.W., Hyun J.Y., Chen L.J., Hwang I., Vargas-Zuniga G., Busschaert N., Gale P.A., Sessler J.L., Shin I. Determinants of ion-transporter cancer cell death. Chem. 2019;5:2079–2098. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesakhov S., Nachliely M., Barvish Z., Aqaqe N., Schwartzman B., Voronov E., Sharoni Y., Studzinski G.P., Fishman D., Danilenko M. Cancer-selective cytotoxic Ca2+ overload in acute myeloid leukemia cells and attenuation of disease progression in mice by synergistically acting polyphenols curcumin and carnosic acid. Oncotarget. 2016;7:31847–31861. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R., Pozzan T. Microdomains of intracellular Ca2+: molecular determinants and functional consequences. Physiol. Rev. 2006;86:369–408. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R., Stefani D. De, Raffaello A., Mammucari C. Mitochondria as sensors and regulators of calcium signaling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:566–578. doi: 10.1038/nrm3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues T., Sieglitz F., Bernardes G.J.L. Natural product modulators of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels as potential anti-cancer agents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:6130–6137. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00916b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang L.J., Ju H.Q., Liu G.P., Tian T., Ma G.L., Lu Y.X., Liu Z.X., Pan R.L., Li R.H., Piao H.L. LncRNA CamK-A regulates Ca2+-signaling-mediated tumor microenvironment remodeling. Mol. Cell. 2018;72:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Salvador L., Andrés-Borderia A., Ferrer-Montiel A., Planells-Cases R. Agonist-and Ca2+-dependent desensitization of TRPV1 channel targets the receptor to lysosomes for degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:19462–19471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.289751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scorrano L., Oakes S.A., Opferman J.T., Cheng E.H., Sorcinelli M.D., Pozzan T., Korsmeyer S.J. BAX and BAK regulation of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+: a control point for apoptosis. Science. 2003;300:135–139. doi: 10.1126/science.1081208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao C., Xiao F., Guo H., Yu J.T., Jin D., Wu C.F., Xi L., Tian L.L. Utilizing polymer micelle to control dye J-aggregation and enhance its theranostic capability. iScience. 2019;22:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2019.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thor H., Hartzell P., Orrenius S. Potentiation of oxidative cell injury in hepatocytes which have accumulated Ca2+ J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:6612–6615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian B.P., Li F.Y., Li R.Q., Hu X., Lai T.W., Lu J.X., Zhao Y., Du Y., Liang Z.Y., Zhu C. Nanoformulated ABT-199 to effectively target Bcl-2 at mitochondrial membrane alleviates airway inflammation by inducing apoptosis. Biomaterials. 2019;192:429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriens J., Janssens A., Prenen J., Nilius B., Wondergem R. TRPV channels and modulation by hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor in human hepatoblastoma (HepG2) cells. Cell Calcium. 2004;36:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace B.D., Wang H.W., Lane K.T., Scott J.E., Orans J., Koo J.S., Venkatesh M., Jobin C., Yeh L.A., Mani S., Redinbo M.R. Alleviating cancer drug toxicity by inhibiting a bacterial enzyme. Science. 2010;330:831–835. doi: 10.1126/science.1191175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan X.Y., Zhong H., Pan W., Li Y.H., Chen Y.Y., Li N., Tang B. Programmed release of dihydroartemisinin for synergistic cancer therapy using a CaCO3 mineralized metal–organic framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;131:14272–14277. doi: 10.1002/anie.201907388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.H., Liang G.H., Zhang W.J., Xing D., Hu X.L. Cascade-promoted photo-chemotherapy against resistant cancers by enzyme-responsive polyprodrug nanoplatforms. Chem. Mater. 2018;30:3486–3498. [Google Scholar]

- Waning J., Vriens J., Owsianik G., Stuwe L., Mally S., Fabian A., Frippiat C., Nilius B., Schwab A. A novel function of capsaicin-sensitive TRPV1 channels: involvement in cell migration. Cell Calcium. 2007;42:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S., Tavares A.J., Dai Q., Ohta S., Audet J., Dvorak H.F., Chan W.C. Analysis of nanoparticle delivery to tumours. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016;1:16014–16025. [Google Scholar]

- Williams G.S.B., Boyman L., Chikando A.C., Khairallah R.J., Lederer W.J. Mitochondrial calcium uptake. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:10479–10481-486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300410110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T.S., Tang M. Review of the effects of manufactured nanoparticles on mammalian target organs. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2018;38:25–40. doi: 10.1002/jat.3499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T.T., Peters A.A., Tan P.T., Roberts-Thomson S.J., Monteith G.R. Consequences of activating the calcium-permeable ion channel TRPV1 in breast cancer cells with regulated TRPV1 expression. Cell Calcium. 2014;56:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L.H., Tong G.H., Song Q.L., Zhu C.Y., Zhang H.L., Shi J.J., Zhang Z.Z. Enhanced intracellular Ca2+ nanogenerator for tumor-specific synergistic therapy via disruption of mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis and photothermal therapy. ACS Nano. 2018;12:6806–6818. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b02034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.K., Ye J.J., Li C.X., Xia Y., Wang Z.Y., Feng J., Zhang X.Z. Cytomembrane-mediated transport of metal ions with biological specificity. Adv. Sci. 2019;6:1900835–1900844. doi: 10.1002/advs.201900835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Song R., Liu Y.Y., Yi Z.G., Meng X.F., Zhang J.W., Tang Z.M., Yao Z.W., Liu Y., Liu X.G., Bu W.B. Calcium-overload-mediated tumor therapy by calcium peroxide nanoparticles. Chem. 2019;5:2171–2182. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Lin L.N., Lu Y., Chen S.F., Dong L.A., Yu S.H. Templating synthesis of preloaded doxorubicin in hollow mesoporous silica nanospheres for biomedical applications. Adv. Mater. 2010;22:5255–5259. doi: 10.1002/adma.201002395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Lu Y., Hu Y., Li J.P., Dong L.A., Lin L.N., Yu S.H. Synthesis of superparamagnetic CaCO3 mesocrystals for multistage delivery in cancer therapy. Small. 2010;6:2436–2442. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Luo Z., Li M.H., Qu Q.Y., Ma X., Yu S.H., Zhao Y.L. A preloaded amorphous calcium carbonate/doxorubicin@ silica nanoreactor for ph-responsive delivery of an anticancer drug. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:919–922. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R.B., Liu X.Y., Yang X.Y., Jin B.A., Shao C.Y., Kang W.J., Tang R.K. Nanomaterial-based organelles protect normal cells against chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1801304–1801311. doi: 10.1002/adma.201801304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen X., Xie C., Jiang Y.Y., Ai X.Z., Xin B.G., Pu K.Y. Semiconducting photothermal nanoagonist for remote-controlled specific cancer therapy. Nano Lett. 2018;18:1498–1505. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen W.Y., Liu Y., Jia X.D., Wu L., Wang C., Jiang X. Reductive surfactant-assisted one-step fabrication of an BiOI/BiOIO3 heterojunction biophotocatalyst for enhanced photodynamic theranostics overcoming tumor hypoxia. Nanoscale Horiz. 2019;4:720–726. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z.W., Yadong Liu Y.D., Zhang M.H., Li C.Z., Yang R.X., Li J., Qian C.G., Sun M.J. Size switchable nanoclusters fueled by extracellular ATP for promoting deep penetration and MRI-guided tumor photothermal therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019;29:1904144–1904155. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z.W., Zhang Q.Y., Yang R.X., Wu H., Zhang M.H., Qian C.G., Chen X.Z., Sun M.J. ATP-charged nanoclusters enable intracellular protein delivery and activity modulation for cancer theranostics. iScience. 2020;23:100872. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.100872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.