Abstract

In this work, boron nitride nanosheets (BNNS) were produced through chemical exfoliation of bulk boron nitride (BN). Furthermore, hydrothermal technique was used to incorporate various concentrations (2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 wt%) of zirconium (Zr) as a dopant. The prepared undoped and doped BN samples were evaluated for its antimicrobial activity against E. coli and S. aureus. Structural analysis was undertaken using x-ray diffraction which identified the presence of hexagonal BN. FTIR and Raman spectroscopy were utilized to outline IR fingerprint and electronic properties of the synthesized material. Morphological information was obtained through micrographs extracted using field emission scanning electron spectroscope (FESEM) and high resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM), while d-spacing was also calculated through HRTEM analysis. Optical properties and emission spectra were examined by applying UV–vis and photoluminescence spectroscope (PL); whereas, band gap analysis was carried out via Tauc plot. Zr-doped BN nanosheets at increasing concentrations (0.5, 1.0 mg/50 μl) revealed enhanced antibacterial activity against E. coli compared to S. aureus (p < 0.05).

Keywords: Boron nitride, Exfoliation, Nanosheets, Hydrothermal, Antimicrobial

Introduction

In the recent years, studies focused on protection from infection through pathogenic micro-organisms have received considerable attention. Such research plays an important role in ensuring the provision of a healthy, reliable, and comfortable living environment. Among these pathogens, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and influenza virus (H1N1) produce terrible effects on human life (Fu et al. 2011). Mukaddas et al. reported that ~ 50 to 70% of deaths result from infection caused by micro-organisms. Similarly, bovine udder glandular tissue inflammation (mastitis) is a major economic threat to dairy industry around the globe. Its potential to transmit zoonotic infections i.e., streptococcal sore throat, leptospirosis, tuberculosis, and brucellosis to humans is a major concern. Bovine mastitis is characterized by chemical and microbiological changes in milk as well as pathological changes in glandular tissues of bovine udder. Infectious etiological agents, especially bacteria, viruses, and fungi, are divided into two categories. Major category consists of Staphylococcus aureas (S. aureus), Streptococci, Coliform, and Corynebacterium pyogenes, whereas minor group includes pathogens such as Corynebacterium bovis and coagulase-negative Staphylococci. These pathogens cause harmful diseases that can severely affect human and animal health (Gnanamani et al. 2003; Haider et al. 2019). On the other hand, antimicrobial resistance depicted by Gram-positive bacterial pathogens such as S. aureus (MRSA) has been increasing at an alarming rate. In view of the above, studies related to antimicrobial, antivirus, and antifungal behavior have received growing attention since 2003 (Naidu et al. 2005; Grassberger et al. 1984).

Research on nanomaterials has inspired scientists to work towards solutions that achieve biocompatibility with no accompanying cytotoxicity (Kıvanç et al. 2018). During recent years, various bio-applications of nanomaterials and their biocompatibility have been investigated (Majewski and Thierry 2007; Yang et al. 2014). Graphene is the most interesting two-dimensional layered material (2D-mats) that exhibits distinctive properties resulting in several applications, especially in biomedical science. Encouraged by the results extracted from graphene, researchers turned their attention to graphene-analogous 2D-mats such as molebdinum-disulphide (MoS2), boron nitride (BN), and tungsten disulphide (WS2). Owing to its specific crystalline and chemical structure, these 2D-mats exhibit distinct properties compared to not only host graphene but also relative to each other (Xu et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2016; Mahmoudi et al. 2018; Ikram et al. 2020a). Various properties of 2D-mats render them attractive for biomedical applications. 2D graphene and its analogous materials have been recommended for use in bioimaging, photothermal therapy, biosensors, and biomedical implants, particularly in antimicrobial applications (Liu et al. 2012,2009; Yang et al. 2010).

Nanomaterials, such as nanosheets, may be formulated for use in environmental applications. As an example, nanomaterials can be used to protect the environment during conventional machining and manufacturing processes that generate pollution due to the use of toxic and corrosive slurries. This is undertaken by employing nanomaterials to develop novel environmental-friendly chemical and mechanical polishing slurries (Zhang et al. 2012a, b, 2013, 2015a, b, 2018, 2019, 2020a; Wang et al. 2018). The use of improved procedures and enhanced slurries enables the fabrication of high-performance devices in semiconductor and microelectronics industries (Zhang et al. 2017a; Qumar et al. 2020; Raza et al. 2019; Ikram et al. 2020b). Such researches have proved to be a landmark in the contribution toward dramatically reducing pollution in industrial processes (Zhang et al. 2020b; Cui et al. 2019a, 2019b).

BN reveals honeycomb-like structure analogous to graphene with periodic arrangement among boron as well as nitrogen atoms. This structure is characterized by substantial sp2 (in-plane) covalent bonding and faint van der Waals forces between the layers (Kostoglou et al. 2015). Moreover, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) possesses excellent physical, chemical, thermal, electrical, optical, and dielectric properties such as high hardness, good chemical inertness, fine electrical insulation, high melting point, superior thermal conductivity and stability, high optical transparency, and low dielectric constant (Kostoglou et al. 2015; Meziani et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2017). Meanwhile, BN is a good insulator material that exhibits a wide band gap of 5.9 eV. Incorporation of transition metal (Co, Mn, Fe, and Zr) in nanosheets as dopant serves to modify its optical, electronic, and thermal properties (Lin et al. 2013). Zirconium exhibits good antibacterial behavior, therefore it serves as a reliable antibacterial agent (Huang et al. 2013a). Incorporation of Zr into BN nanosheets enhances its antibacterial activity. The literature studies indicate an enhancement of antibacterial effect due to incorporation of doping (Silva et al. 2018; Merlo et al. 2018). In addition, antibacterial activity depends upon shape, size, bonding as well as surface energy of the material. Interaction of BN nanosheets to exhibit biocompatibility has been reported using molecular dynamic simulation. Few experimental investigations have been reported to highlight the biocompatibility of BN nanosheets with kidney such that the BN nanosheets with optimum length of 10 mm, synthesized by chemical vapor deposition process exhibited zero cytotoxicity (Mateti et al. 2018). Cytotoxic and cell viability experiments showed direct proportionality between concentration and exposure time of BN nanosheets with regard to its biocompatibilty performance (Horvath et al. 2011; Ciofani et al. 2010).

In this study, exfoliation of bulk BN powder was carried out to produce nanosheets, while zirconium (Zr) was incorporated as a doping agent using hydrothermal process. Various characterization techniques were employed to evaluate the effect of Zr doping in BN nanosheets. The current study was aimed at investigating the bactericidal action of Zr-doped BN nanosheets against E. coli and S. aureus bacteria that are widely known to cause bovine mastitis.

Experimental procedure

Materials

Bulk BN powder (98%) and dimethylformamide (DMF) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). Zirconium nitrate hydrate (Zn(NO3)4·H2O was purchased from BDH laboratory supplies (England). Chemicals employed in this research were utilized without any additional purification.

Exfoliation and synthesis of Zr-doped BN

Chemical exfoliation approach was adopted to produce BN nanosheets. Primarily, 5 g bulk BN powder was dissolved in 200 ml DMF solution under continuous stirring for 20 min to prepare the stock solution. Prepared stock solution was vigorously sonicated for 12 h. After sonication, BN nanosheets were collected by centrifugation of stock solution at 6000 rpm. Subsequently, various concentrations (2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 wt%) of zirconium nitrate hydrate (Zr(NO3)4.H2O) were incorporated into the collected BN nanosheets using hydrothermal technique. For this purpose, BN nanosheets and Zr(NO3)4·H2O were dispersed in 100 ml deionized water (DIW) under stirring for 20 min. The resulting suspension was transferred into autoclave, placed in vaccum oven at 200 °C for 124 h as schematically represented in Fig. 1. Finally, autoclave was allowed to cool down to room temperature and the obtained solution was dried on hot plate at 100–120 °C to get a fine powder product.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of exfoliation of BN and synthesis of Zr-doped BN

Antibacterial activity

The in vitro antimicrobial behavior of Zr-doped BN nanosheets against S. aureus and E. coli was evaluated through bovine mastitic milk studied with agar well diffusion process. The petri dishes were wiped with Manitol salt agar [MSA] for S. aureus and Macconkey agar [MA] for E. coli. Different concentrations of Zr-doped BN nanosheets (0.5 mg/50 µl) and (1.0 mg/50 µl) were used and 6-mm diameter wells were prepared using sterile cork borer. In comparison, ciprofloxacin (0.005 mg/50 µl) was used as +ve and DIW (50 µl) for −ve control. The antimicrobial potential as per inhibition zones (mm) was evaluated after incubation using a Vernier caliper at 37 °C, overnight.

Materials characterization

Various characterizations were performed to assess the properties of the prepared material. Structural properties were examined through X-ray diffractometer (XRD), PAN analytical X’pert Pro using Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm), 2θ varying from 5° to 80°. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) Perkin Elmer spectrometer and DXR Raman microscope (Thermoscientific) using diode laser (λ = 532 nm) were employed to investigate IR and structural molecular fingerprint. Optical properties were investigated through UV–visible Genesys 10S and Photoluminescence spectrum JASCO FP-8200 spectrofluorometer. Morphological examination and d-spacing measurements were carried out with JSM-6460LV field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) and high resolution transmission electron microscope (HR-TEM) equipment Philips CM30, along with JEOL JEM 2100F.

Results and discussion

X-ray diffraction was employed to identify crystal structure and phase constitution as well as to measure crystallite size, as presented in Fig. 2a. Obtained XRD patterns reveal peaks positioned at 2θ ~ 26.70°, 41.69°, 43.91°, and 50.13°. Main characteristic pattern located at 26.70 was readily indexed as 002 plane, while other diffraction peaks were indexed as 100, 101, and 102 planes, respectively, which correlate strongly with JCPDS reference # 00-034-0421 (Yuan et al. 2017; Tang et al. 2019). Significant peak was observed at 26.70° that relates to h-BN, while the interplanar spacing (d002) evaluated through Bragg’s law was 0.339 nm (Huang et al. 2013b). Peak intensity in control and Zr-doped samples showed minor shift in diffraction angle which indicates the presence of dopant. Electron diffraction profiles obtained from SAED patterns are displayed in Fig. 2b–d. Obtained profiles exhibited nanosheets with crystalline nature as is apparent from the diffraction rings. Characteristic peak of BN indexed as 002 coincided with the innermost hollow diffraction profile (Zhong et al. 2017).

Fig. 2.

A XRD reflections of pure and various doped concentrations (2.5, 5, 7.5 and 10 wt% Zr) of BN, b–d SAED profiles of (0, 2.5 and 10 wt%), and e FTIR spectra of pure and various doped concentrations (2.5, 5, 7.5 and 10 wt% Zr) of BN

FTIR was used to analyze the IR fingerprint of pristine and doped BN, as demonstrated in Fig. 2e. Observed spectra exhibited two core peaks that correspond to h-BN at 740 as well as at 1355 cm−1. Primary peak is attributed to B–N–B bending vibration (A2u-out of plane), while secondary peak is ascribed to B–N stretching vibration (E1u-in plane) (Li et al. 2017; Ding et al. 2018). Peaks recorded at 1160 and 1560 cm−1 correspond to C=O and B–N–O, respectively. Meanwhile, some peaks in pure sample at 1100, 1020, and 924 cm−1 are correspondingly related to B–OH, C–O, and B–N–O (Li et al. 2013; Sudeep et al. 2015). A minor peak at 3155 cm−1 is owed to B–OH bond that exists due to moisture (Gautam et al. 2016). In short, FTIR spectra proved the formation of h-BN phase.

Raman spectroscopy was employed to understand the electronic properties and structural fingerprint of un-doped and doped BN as illustrated in Fig. 3a. Raman spectra indicate two minor peaks centered at ~ 529 and ~ 883 cm−1, which were attributed to background fluorescence (Štengl et al. 2014). Spectra exhibit main characteristic peak at ~ 1364 cm−1 that refers to E2g phonon mode for h-BN caused by phonon dispersion and bond vibration (B–N) within the crystallographic plane (Feng and Sajjad 2012; Arenal et al. 2006). Red shift and peak broadening in Raman spectra were observed upon incorporation of dopant owing to the faint interaction between h-BN layers (Mahdizadeh et al. 2017).

Fig. 3.

a Raman spectra of host BN and Zr-doped BN, b PL spectra

PL spectroscopy was employed to evaluate excitons migration phenomenon of control and Zr-doped BN, as illustrated in Fig. 3b. Obtained PL spectra were observed with excitation and emission wavelength of 220 and 310 nm, respectively, as nanomaterials are quite sensitive to excitation wavelength. PL spectra indicate wide band centered at ~ 325 nm (blue emission) that is assigned to vacancies present, which epitomize as electron–hole recombination, adsorption, activation, and photosensitivity centers (Lee and Song 2017). Another peak observed at ~ 480 nm reveals that the intensity increases sharply from undoped (control sample) to doped sample; whereas, for 10 wt% Zr-doped BN, it reduces abruptly. The most intense peak implies maximum recombination of photogenerated charges where the lowest intensity indicates separation of electron–holes (Silly et al. 2007). Therefore, it is concluded that an excitation-dependent PL behavior is observed that is in agreement with the previously reported results (Wu et al. 2017).

Optical properties of pure BN and Zr-doped BN as measured with UV–vis. spectroscope are expressed in Fig. 4a. Extracted spectra demonstrate absorption peak at 210 nm stretched out in UV region (see Fig. 4a) which corresponds to optical band gap of 5.74 eV. The calculated band gap matched well with the reported values. No absorption peak at lower or higher energy side was identified which indicates the existence of dense structural defects (Mahdizadeh et al. 2017). The literature survey indicates that the band gap for multilayer h-BN was 6.07 eV; whereas, single layer exhibits a band gap of 5.56–5.92 eV. Besides these, theoretical analysis reveals a band gap of 6.0 eV. This difference in band gap is due to electronic band dispersion caused by layer-to-layer interaction (Zhang et al. 2017b; Kumbhakar et al. 2015). Upon incorporation of Zr, red shift in wavelength was observed that serves to decrease band gap from 5.72 to 4.55 eV as demonstrated in Fig. 4b via Tauc plot. This decrease in band gap coincides with the experimental observation of increase in crystallite size as calculated using XRD analysis.

Fig. 4.

a UV–vis. spectra of control BN and Zr-doped BN, b Tauc plot for band gap

Morphological examination of pure and Zr-incorporated BN was undertaken from the micrographs obtained through FESEM as represented in Fig. 5a–e. From FESEM micrograph in Fig. 5a, it can be seen that the obtained particles exhibited aggregated nanosheets structure. Smooth surface of nanosheets compact with uniform features and round edges was also observed. Meanwhile, doped samples shown in Fig. 6b–e indicate high agglomeration with the presence of Zr above nanosheets. Furthermore, microstructure of samples was investigated through HRTEM study as shown in Fig. 5a′–d′. Typical HRTEM images of control and doped-BN indicate curled edges along with intermediate transparency. Effect of doping can be seen from obtained micrographs. Dark spots on HRTEM images depict decoration of Zr on BN nanosheets. The observed morphology of prepared samples affirms that chemical exfoliation did not produce adverse effect on nanosheets (Özkan et al. 2019). It is worth mentioning that the viability of cells exposed to bulk BN and nanosheets varied. As BN is a chemically inert material, altering its size from bulk to micro/nanoscale affects BN’s biocompatibility. Pure and Zr-doped BN nanosheets as indicated in Fig. 5(a-d) are produced as a result of chemical exfoliation of bulk BN which exhibit good antimicrobial activity because of their change in size from bulk to nanoscale (Mateti et al. 2018). Experimental results indicate that FESEM and HRTEM analysis agree well with each other.

Fig. 5.

a–d FESEM micrographs of bare and various doped concentrations (5, 7.5 and 10 wt% Zr) of BN, a′–d′ HRTEM micrographs with corresponding inset (50 nm)

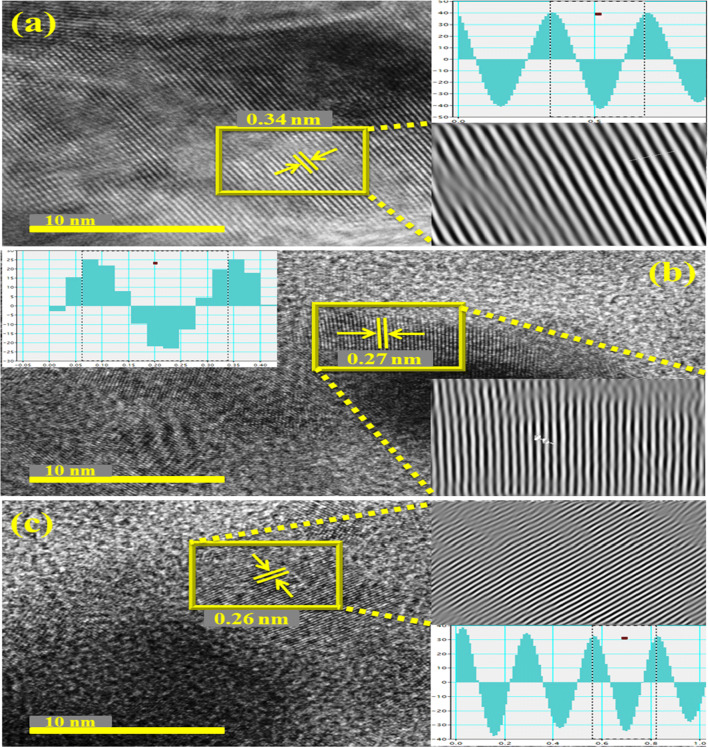

Fig. 6.

a Interlayer spacing measurements of host BN, b, c 2.5 and 5 wt% Zr-doped BN

Average interplanar distance between nanosheets was evaluated through plane view HRTEM images as illustrated in Fig. 6a–c. Extracted HRTEM micrographs indicate that nanosheets consist of crystalline phase along with a significant number of uniform layers. Average d-spacing for BN nanosheets is 0.34 nm which corresponds well to previously cited results (Huang et al. 2013b). Meanwhile, for 2.5 and 5 wt% doped nanosheets, d-spacing befits as 0.27 and 0.26 nm, respectively. Besides, d-spacing was evaluated employing inverse fast Fourier transform (IFFT) (see inset of Fig. 6).

The antimicrobial action of Zr-doped BN nanosheets was investigated in vitro through inhibition zones measurements (mm) using agar well diffusion assay against S. aureus and E. coli as shown in Fig. 7a–d. Extracted results from antibacterial activity specify excellent effect on inhibition zones and doped-BN nanosheets. It is worth noting that excellent antimicrobial efficacy of Zr-doped BN nanosheets was observed against bacterial strains as illustrated.

Fig. 7.

a–d In vitro antimicrobial activity of Zr-doped BN at low and high concentration for S. aureus, a′–d′ low and high concentration for E. coli, e, f graphical representation

The in vitro antimicrobial activity of various Zr-doped BN nanosheet samples was investigated with agar well diffusion method by calculating inhibition zones in mm as depicted in Fig. 7 and Table 1. All results demonstrate antimicrobial efficacy against Gram-positive and negative bacterial strain. Significant inhibition zones were observed for doped BN (2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 wt% Zr) against S. aureus in the range (0–1 mm) and (1–3.6 mm) for low and high concentrations as shown in Fig. 7a-d, and (0–3.6 mm) and (2.55–5 mm) at low and high concentrations against E. coli as shown in Fig. 7a′–d′. BN-doped nanosheets exhibited (0 mm) inhibition at low concentration against both bacterial strains. Increase in doping resulted in direct proportion increase in inhibition zones at high concentrations for E. coli and S. aureus as shown in Fig. 7a–d′. All results are compared to ciprofloxacin (9 mm) and DIW (0 mm). In general, Zr-doped BN nanosheets revealed enhanced antibacterial activity against E. coli (g-negative) compared to S. aureus (g-positive) as graphically represented in Fig. 7e–f.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial activity of Zr-doped BN nanosheets

| Sample [Zr (%):BN] | S. aureus E. coli | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition zone (mm) | Inhibition zone (mm) | |||

| 0.5 mg/50 μl | 1.0 mg/50 μl | 0.5 mg/50 μl | 1.0 mg/50 μl | |

| 0.025:1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2.55 |

| 0.05:1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 0.075:1 | 0 | 2.75 | 2.5 | 4.35 |

| 0.1:1 | 1 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 5 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| DIW | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Generation of strong rate surface-oxygen species can be achieved through antimicrobial response of Zr-doped BN nanosheets by formation of inhibition zone. Antimicrobial activity in terms of inhibition zones (mm) increased due to increased wt% doping of Zr on BN that produces maximum cationic availability. Antimicrobial effectiveness depends upon size and concentration and exhibits inverse relationship to the size of doped nanosheets (Haider et al. 2019). Small-sized NS produces reactive oxygen species [ROS] which stay more effectively in implants in bacterial membrane resulting in cytoplasmic-contents extrusion and annihilation of bacteria. Second, the strong cationic interaction of Zr4+ with negative charged bacterial membrane parts resulted in enhanced bactericidal activity at increasing concentrations by inducing lysis and collapse of bacterial cell (Haider et al. 2020).

Conclusion

In this study, successful preparation of BN nanosheets was achieved by chemical exfoliation; further, various Zr dopant concentrations (2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 wt%) were incorporated using hydrothermal method. Successful incorporation of dopants was tested through XRD, FTIR, Raman, PL, UV–vis, FESEM, and HR-TEM. Hexagonal phase of BN was affirmed via XRD analysis, while FTIR spectra indicated the presence of sp2 bonded B–N (in-plane) and B–N–B (out of plane) bending vibrations that belonged to IR fingerprints of BN nanosheets. Raman analysis showed E2g active band of BN whereas PL spectra indicated excitons recombination and transfer rate. Spectra evaluated by means of UV–Vis. spectroscopy indicated an absorption that lies in the deep UV region which makes it suitable for use in optoelectronic devices; however, band gap decreases with the incorporation of dopant due to quantum confinement effect. Sheet-like morphology was confirmed through FESEM and HR-TEM analysis. Calculated interlayer spacing (0.34 nm) matched well with that reported in the literature. In conclusion, significant inhibition zones were observed for Zr-doped BN against S. aureus in the range (0–1 mm) and (1–3.6 mm) at low and high concentrations and similarly, (0–3.6 mm) and (2.55–5 mm) for E. coli. Zr-doped BN nanosheets at high concentrations (0.5, 1.0 mg/50 μl) resulted in enhanced antibacterial activity for E. coli compared with S. aureus.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the financial support received from the Higher Education Commission, Pakistan, through start research Grant project #21-1669/SRGP/R&D/HEC/2017, and CAS-TWAS President’s Fellowship for International PhD Students, China. Support of the Research Institute at the King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, is appreciated.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

M. Ikram and I. Jahan are equally contributed.

References

- Arenal R, Ferrari AC, Reich S, Wirtz L, Mevellec JY, Lefrant S, Rubio A, Loiseau A. Raman spectroscopy of single-wall boron nitride nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2006;6(8):1812–1816. doi: 10.1021/nl0602544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciofani G, Danti S, D’Alessandro D, Moscato S, Menciassi A. Assessing cytotoxicity of boron nitride nanotubes: interference with the MTT assay. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;394(2):405–411. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Zhang Z, Liu D, Zhang D, Hu W, Zou L, Lu Y, Zhang C, Lu H, Tang C, Jiang N. Unprecedented piezoresistance coefficient in strained silicon carbide. Nano Lett. 2019;19(9):6569–6576. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b02821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Zhang Z, Jiang H, Liu D, Zou L, Guo X, Lu Y, Parkin IP, Guo D. Ultrahigh recovery of fracture strength on mismatched fractured amorphous surfaces of silicon carbide. ACS Nano. 2019;13(7):7483–7492. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b02658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Torres-Davila F, Khater A, Nash D, Blair R, Tetard L. Defect engineering in boron nitride for catalysis. MRS Commun. 2018;8(3):1236–1243. [Google Scholar]

- Feng PX, Sajjad M. Few-atomic-layer boron nitride sheets syntheses and applications for semiconductor diodes. Mater Lett. 2012;89:206–208. [Google Scholar]

- Fu X, Shen Y, Jiang X, Huang D, Yan Y. Chitosan derivatives with dual-antibacterial functional groups for antimicrobial finishing of cotton fabrics. Carbohyd Polym. 2011;85(1):221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam C, Tiwary CS, Machado LD, Jose S, Ozden S, Biradar S, Galvao DS, Sonker RK, Yadav BC, Vajtai R, Ajayan PM. Synthesis and porous h-BN 3D architectures for effective humidity and gas sensors. RSC Adv. 2016;6(91):87888–87896. [Google Scholar]

- Gnanamani A, Priya KS, Radhakrishnan N, Babu M. Antibacterial activity of two plant extracts on eight burn pathogens. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;86(1):59–61. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassberger MA, Turnowsky F, Hildebrandt J. Preparation and antibacterial activities of new 1,2,3-diazaborine derivatives and analogs. J Med Chem. 1984;27(8):947–953. doi: 10.1021/jm00374a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider A, Ijaz M, Imran M, Naz M, Majeed H, Khan JA, Ali MM, Ikram M. Enhanced bactericidal action and dye degradation of spicy roots’ extract-incorporated fine-tuned metal oxide nanoparticles. Appl Nanosci. 2019;20:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Haider A, Ijaz M, Ali S, Haider J, Imran M, Majeed H, Shahzadi I, Ali MM, Khan JA, Ikram M. Green synthesized phytochemically (Zingiber officinale and Allium sativum) reduced nickel oxide nanoparticles confirmed bactericidal and catalytic potential. Nanosc Res Lett. 2020;15(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s11671-020-3283-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath L, Magrez A, Golberg D, Zhi C, Bando Y, Smajda R, Horvath E, Forro L, Schwaller B. In vitro investigation of the cellular toxicity of boron nitride nanotubes. ACS Nano. 2011;5(5):3800–3810. doi: 10.1021/nn200139h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HL, Chang YY, Weng JC, Chen YC, Lai CH, Shieh TM. Anti-bacterial performance of zirconia coatings on titanium implants. Thin Solid Films. 2013;528:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Chen C, Ye X, Ye W, Hu J, Xu C, Qiu X. Stable colloidal boron nitride nanosheet dispersion and its potential application in catalysis. J Mater Chem A. 2013;1(39):12192–12197. [Google Scholar]

- Ikram M, Jahan I, Haider A, Hassan J, Ul-Hamid A, Imran M, Ali S. Application of chemically exfoliated boron nitride nanosheets doped with co to remove organic pollutants rapidly from textile water. Nanosc Res Lett. 2020;15(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s11671-020-03315-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikram M, Haider A, Naz S, Imran M, Haider J, Ghaffar A. Bi-metallic Ag/Cu incorporated into chemically exfoliated MoS2 nanosheets to enhance antibacterial potential: insilico molecular docking studies. Nanotechnology. 2020;20:20. doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/ab8087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TH, Ko EH, Nam J, Shim SE, Park DW. Preparation of hexagonal boron nitride nanoparticles by non-transferred arc plasma. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2017;17(12):9217–9223. [Google Scholar]

- Kıvanç M, Barutca B, Koparal AT, Göncü Y, Bostancı SH, Ay N. Effects of hexagonal boron nitride nanoparticles on antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities, cell viability. Mater Sci Eng C. 2018;91:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostoglou N, Polychronopoulou K, Rebholz C. Thermal and chemical stability of hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) nanoplatelets. Vacuum. 2015;112:42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kumbhakar P, Kole AK, Tiwary CS, Biswas S, Vinod S, Taha-Tijerina J, Chatterjee U, Ajayan PM. Nonlinear optical properties and temperature-dependent UV–Vis absorption and photoluminescence emission in 2D hexagonal boron nitride nanosheets. Adv Opt Mater. 2015;3(6):828–835. [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Song SH. Ultra-thin ultraviolet cathodoluminescent device based on exfoliated hexagonal boron nitride. RSC Adv. 2017;7(13):7831–7835. [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Xiao X, Xu X, Lin J, Huang Y, Xue Y, Jin P, Zou J, Tang C. Activated boron nitride as an effective adsorbent for metal ions and organic pollutants. Sci Rep. 2013;3:3208. doi: 10.1038/srep03208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Zhu S, Zhang M, Wu P, Pang J, Zhu W, Jiang W, Li H. Tuning the chemical hardness of boron nitride nanosheets by doping carbon for enhanced adsorption capacity. ACS Omega. 2017;2(9):5385–5394. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.7b00795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Ye X, Johnson RS, Guo H. First-principles investigations of metal (Cu, Ag, Au, Pt, Rh, Pd, Fe Co, and Ir) doped hexagonal boron nitride nanosheets: stability and catalysis of CO oxidation. J Phys Chem C. 2013;117(33):17319–17326. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Tabakman S, Welsher K, Dai H. Carbon nanotubes in biology and medicine: in vitro and in vivo detection, imaging and drug delivery. Nano Res. 2009;2(2):85–120. doi: 10.1007/s12274-009-9009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Dong X, Chen P. Biological and chemical sensors based on graphene materials. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41(6):2283–2307. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15270j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdizadeh A, Farhadi S, Zabardasti A. Microwave-assisted rapid synthesis of graphene-analogue hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) nanosheets and their application for the ultrafast and selective adsorption of cationic dyes from aqueous solutions. RSC Adv. 2017;7(85):53984–53995. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi T, Wang Y, Hahn YB. Graphene and its derivatives for solar cells application. Nano Energy. 2018;47:51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Majewski P, Thierry B. Functionalized magnetite nanoparticles—synthesis, properties, and bio-applications. Crit Rev Solid State Mater Sci. 2007;32(3–4):203–215. [Google Scholar]

- Mateti S, Wong CS, Liu Z, Yang W, Li Y, Li LH, Chen Y. Biocompatibility of boron nitride nanosheets. Nano Res. 2018;11(1):334–342. [Google Scholar]

- Merlo A, Mokkapati VRSS, Pandit S, Mijakovic I. Boron nitride nanomaterials: biocompatibility and bio-applications. Biomater Sci. 2018;6(9):2298–2311. doi: 10.1039/c8bm00516h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meziani MJ, Song WL, Wang P, Lu F, Hou Z, Anderson A, Maimaiti H, Sun YP. Boron nitride nanomaterials for thermal management applications. ChemPhysChem. 2015;16(7):1339–1346. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201402814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidu BN, Sorenson ME, Bronson JJ, Pucci MJ, Clark JM, Ueda Y. Synthesis, in vitro, and in vivo antibacterial activity of nocathiacin I thiol-Michael adducts. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15(8):2069–2072. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özkan A, Atar N, Yola ML. Enhanced surface plasmon resonance (SPR) signals based on immobilization of core-shell nanoparticles incorporated boron nitride nanosheets: development of molecularly imprinted SPR nanosensor for anticancer drug, etoposide. Biosens Bioelectron. 2019;130:293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2019.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qumar U, Ikram M, Imran M, Haider A, Ul-Hamid A, Haider J, Riaz KN, Ali S. Synergetic effect of Bi-doped exfoliated MoS2 nanosheets on its bactericidal and dye degradation potential. Dalton Trans. 2020;20:20. doi: 10.1039/d0dt00924e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza A, Ikram M, Aqeel M, Imran M, Ul-Hamid A, Riaz KN, Ali S. Enhanced industrial dye degradation using Co doped in chemically exfoliated MoS2 nanosheets. Appl Nanosc. 2019;20:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Silly MG, Jaffrennou P, Barjon J, Lauret JS, Ducastelle F, Loiseau A, Obraztsova E, Attal-Tretout B, Rosencher E. Luminescence properties of hexagonal boron nitride: cathodoluminescence and photoluminescence spectroscopy measurements. Phys Rev B. 2007;75(8):085205. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva WM, Ferreira TH, de Morais CA, Leal AS, Sousa EMB. Samarium doped boron nitride nanotubes. Appl Radiat Isot. 2018;131:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2017.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Štengl V, Henych J, Kormunda M. Self-assembled BN and BCN quantum dots obtained from high intensity ultrasound exfoliated nanosheets. Sci Adv Mater. 2014;6(6):1106–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Sudeep PM, Vinod S, Ozden S, Sruthi R, Kukovecz A, Konya Z, Vajtai R, Anantharaman MR, Ajayan PM, Narayanan TN. Functionalized boron nitride porous solids. RSC Adv. 2015;5(114):93964–93968. [Google Scholar]

- Tang CY, Zulhairun AK, Wong TW, Alireza S, Marzuki MSA, Ismail AF. Water transport properties of boron nitride nanosheets mixed matrix membranes for humic acid removal. Heliyon. 2019;5(1):e01142. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Zhang Z, Chang K, Cui J, Rosenkranz A, Yu J, Lin CT, Chen G, Zang K, Luo J, Jiang N. New deformation-induced nanostructure in silicon. Nano Lett. 2018;18(7):4611–4617. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b01910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Lv X, Wang J, Xie J. Integrating AgI/AgBr biphasic heterostructures encased by few layer h-BN with enhanced catalytic activity and stability. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;496:434–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Liang T, Shi M, Chen H. Graphene-like two-dimensional materials. Chem Rev. 2013;113(5):3766–3798. doi: 10.1021/cr300263a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K, Zhang S, Zhang G, Sun X, Lee ST, Liu Z. Graphene in mice: ultrahigh in vivo tumor uptake and efficient photothermal therapy. Nano Lett. 2010;10(9):3318–3323. doi: 10.1021/nl100996u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Li J, Liang T, Ma C, Zhang Y, Chen H, Hanagata N, Su H, Xu M. Antibacterial activity of two-dimensional MoS 2 sheets. Nanoscale. 2014;6(17):10126–10133. doi: 10.1039/c4nr01965b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan F, Jiao W, Yang F, Liu W, Liu J, Xu Z, Wang R. Scalable exfoliation for large-size boron nitride nanosheets by low temperature thermal expansion-assisted ultrasonic exfoliation. J Mater Chem C. 2017;5(25):6359–6368. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Huo F, Zhang X, Guo D. Fabrication and size prediction of crystalline nanoparticles of silicon induced by nanogrinding with ultrafine diamond grits. Scr Mater. 2012;67(7–8):657–660. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Song Y, Xu C, Guo D. A novel model for undeformed nanometer chips of soft-brittle HgCdTe films induced by ultrafine diamond grits. Scr Mater. 2012;67(2):197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Huo Y, Guo D. A model for nanogrinding based on direct evidence of ground chips of silicon wafers. Sci China Technol Sci. 2013;56(9):2099–2108. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Wang B, Kang R, Zhang B, Guo D. Changes in surface layer of silicon wafers from diamond scratching. CIRP Ann. 2015;64(1):349–352. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Guo D, Wang B, Kang R, Zhang B. A novel approach of high speed scratching on silicon wafers at nanoscale depths of cut. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16395. doi: 10.1038/srep16395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Hou J, Chen S, Xiong C, Liu H, Jin Y, Wang J, He Q, Zhao R, Nie Z. Rapidly probing antibacterial activity of graphene oxide by mass spectrometry-based metabolite fingerprinting. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28045. doi: 10.1038/srep28045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Cui J, Wang B, Wang Z, Kang R, Guo D. A novel approach of mechanical chemical grinding. J Alloy Compd. 2017;726:514–524. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Feng Y, Wang F, Yang Z, Wang J. Two dimensional hexagonal boron nitride (2D-hBN): synthesis, properties and applications. J Mater Chem C. 2017;5(46):11992–12022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Shi Z, Du Y, Yu Z, Guo L, Guo D. A novel approach of chemical mechanical polishing for a titanium alloy using an environment-friendly slurry. Appl Surf Sci. 2018;427:409–415. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Cui J, Zhang J, Liu D, Yu Z, Guo D. Environment friendly chemical mechanical polishing of copper. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;467:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Liao L, Wang X, Xie W, Guo D. Development of a novel chemical mechanical polishing slurry and its polishing mechanisms on a nickel alloy. Appl Surf Sci. 2020;506:144670. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Du Y, Huang S, Meng F, Chen L, Xie W, Chang K, Zhang C, Lu Y, Lin CT, Li S. Macroscale superlubricity: macroscale superlubricity enabled by graphene-coated surfaces (Adv. Sci. 4/2020) Adv Sci. 2020;7(4):2070023. doi: 10.1002/advs.201903239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong B, Zhang X, Xia L, Yu Y, Wen G. Large-scale fabrication and utilization of novel hexagonal/turbostratic composite boron nitride nanosheets. Mater Des. 2017;120:266–272. [Google Scholar]