Abstract

Background & Aims:

Patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) can be listed for liver transplantation (LT) because LT is the only curative treatment option. We evaluated whether the clinical course of ACLF, particularly ACLF-3, between the time of listing and LT affects 1-year post-transplant survival.

Methods:

We identified patients from the United Network for Organ Sharing database who were transplanted within 28 days of listing and categorized them by ACLF grade at waitlist registration and LT, according to the EASL-CLIF definition.

Results:

A total of 3,636 patients listed with ACLF-3 underwent LT within 28 days. Among those transplanted, 892 (24.5%) recovered to no ACLF or ACLF grade 1 or 2 (ACLF 0–2) and 2,744 (75.5%) had ACLF-3 at transplantation. One-year survival was 82.0% among those transplanted with ACLF-3 vs. 88.2% among those improving to ACLF 0–2 (p <0.001). Conversely, the survival of patients listed with ACLF 0–2 who progressed to ACLF-3 at LT (n = 2,265) was significantly lower than that of recipients who remained at ACLF 0–2 (n = 17,631) at the time of LT (83.8% vs. 90.2%, p <0.001). Cox modeling demonstrated that recovery from ACLF-3 to ACLF 0–2 at LT was associated with reduced 1-year mortality after transplantation (hazard ratio 0.65; 95% CI 0.53–0.78). Improvement in circulatory failure, brain failure, and removal from mechanical ventilation were also associated with reduced post-LT mortality. Among patients >60 years of age, 1-year survival was significantly higher among those who improved from ACLF-3 to ACLF 0–2 than among those who did not.

Conclusions:

Improvement from ACLF-3 at listing to ACLF 0–2 at transplantation enhances post-LT survival, particularly in those who recovered from circulatory or brain failure, or were removed from the mechanical ventilator. The beneficial effect of improved ACLF on post-LT survival was also observed among patients >60 years of age.

Keywords: UNOS database, DRI, Organ failure, MELD-Na score

Graphical abstract

Lay summary:

Liver transplantation (LT) for patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure grade 3 (ACLF-3) significantly improves survival, but 1-year survival probability after LT remains lower than the expected outcomes for transplant centers. Our study reveals that among patients transplanted within 28 days of waitlist registration, improvement of ACLF-3 at listing to a lower grade of ACLF at transplantation significantly enhances post-transplant survival, even among patients aged 60 years or older. Subgroup analysis further demonstrates that improvement in circulatory failure, brain failure, or removal from mechanical ventilation have the strongest impact on post-transplant survival.

Introduction

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is associated with severe systemic inflammation and is characterized by acute hepatic decompensation, development of organ failures, and high 28-day mortality.1–3 The short-term mortality of patients with ACLF grade 3 (ACLF-3), defined as the development of 3 or more organ failures,1 is particularly high, approaching 80% at 28-days4–6 and possibly surpassing that of acute liver failure.7 In certain patients with ACLF-3, liver transplantation (LT) may be the only viable treatment. However, data regarding LT for individuals with ACLF-3 indicate a reduced survival probability, ranging from less than 50%8,9 to 80% at 1 year.10,11 Although this suggests a greater likelihood of survival than supportive care without transplantation, the limited availability of donor organs necessitates judicious selection of transplant recipients.

Given the lower patient survival rates associated with transplantation for ACLF-3 than for no ACLF or ACLF grades 1 and 2 (ACLF 0–2), further analysis is warranted to optimize post-LT survival rates in this population. One approach is to direct care based on the recovery of organ failure(s) (both number and type) prior to transplantation. In the non-transplant setting, data from the CANONIC study suggested that ACLF is a dynamic syndrome and a reduction in ACLF grade improves spontaneous survival, whereas an increase in the severity of ACLF portends high mortality.1,12 In a small proof of concept retrospective investigation, greater post-LT survival was observed among patients with ACLF who had recovery of at least 1 organ system failure at the time of transplantation.13 However, given the small number of patients with ACLF-3 (n = 29) in that study, additional research remains necessary to determine whether improvement in organ system failures augments post-LT survival, particularly among patients with ACLF-3 who have the greatest need for LT but the lowest post-LT survival.

The primary aim of our study was to assess the impact of downgrading the severity of ACLF on post-LT survival, among patients initially listed with ACLF-3. We hypothesized that patients who improved from ACLF-3 at waitlist registration to ACLF 0–2 at LT would have significantly greater 1-year post-LT survival than recipients listed with ACLF-3 who still had ACLF-3 at transplantation. We also explored the impact of timing of LT, recipient age, and recovery from specific organ failures on patient survival after LT.

Materials and methods

The study protocol was approved as exempt from review by the institutional review board at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. The study and analysis of this study was performed consistent with STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) guidelines.14

United network for organ sharing database analysis

From the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) registry, we evaluated patients aged 18 or older who were listed for liver transplantation from 2004 to 2017, to allow for 1 year of post-LT follow up. Patients listed as status-1a or who underwent multi-organ transplantation were excluded. We decided, however, to include patients who underwent simultaneous liver and kidney transplantation (SLKT) given the substantial rise in performance of this operation in the United States since 2002.15 Additionally, we excluded patients who were re-transplanted, since the etiology of their organ dysfunction may be secondary to post-LT complications as opposed to end-stage liver disease (ESLD). We collected data regarding patient characteristics at the time of waitlist registration and both patient and donor organ characteristics at transplantation, including donor risk index (DRI). Regarding etiology of liver disease, patients were considered as having non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) as their primary etiology of cirrhosis if they were identified either as having NASH-related cirrhosis or cryptogenic cirrhosis with a concurrent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus or a body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2.16 Additional classifications included HCV, HBV, and alcohol-related liver disease (ALD). To avoid misclassification, patients who were categorized as having both HCV infection and ALD were considered as having HCV, due to a lack of data regarding alcohol use.

Study population

Patients with ACLF at the time of waitlist registration were identified based on the European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure (EASL-CLIF) criteria of having a single hepatic decompensation and of the following organ failures: single renal failure, single non-renal organ failure with renal dysfunction or hepatic encephalopathy, or 2 non-renal organ failures (Table S1).1,6 Regarding decompensating events, only the presence of ascites or hepatic encephalopathy were assessed, as information regarding variceal hemorrhage and bacterial infection were unavailable. Specific organ failures were determined according to the CLIF consortium organ failures score for coagulopathy, liver failure, renal dysfunction and renal failure, brain failure, and circulatory failure.1 We used mechanical ventilation as a surrogate marker of respiratory failure. Grade of ACLF was determined based on the number of organ failures at listing and transplantation (Table S1).

We then categorized patients as having either ACLF-3 (cases) or ACLF 0–2 (controls) at the time of waitlist registration. We also classified patients according to ACLF grade at transplantation, among those transplanted within 28 days of listing. We chose a time period of transplantation within 28 days, since prior studies have demonstrated that the 28-day mortality among patients with ACLF-3 is 80% or greater.1,12 The primary outcome for our analysis was patient survival at 1-year after LT.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Stata statistical package (version 14, Stata Corporations, TX). Comparisons were made utilizing Chi-square testing for categorical variables and Student’s t test or Rank sum testing for continuous variables between 2 groups. For our post-LT analysis, we compared 1-year survival probability among the different groups of transplanted patients, utilizing Kaplan-Meier methods, with differences in survival probabilities assessed by log-rank testing.

We additionally developed univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models to evaluate the association between improvement in ACLF-3 between listing and transplantation and 1-year post-LT mortality. Variables were selected for the univariable model a priori based on review of the literature regarding patient and donor characteristics that affect survival after transplantation. After performing univariable analysis, the independent factors that were considered significant (p <0.01) were then incorporated into the multivariable model. The impact of recovery from specific organ failures on post-LT survival was also investigated using Cox proportional hazards regression. As there was less than 5% missing data regarding the variables incorporated into our models, we did not impute for missing information. Goodness of fit was tested using Cox-Snell residuals.

Results

Study population

From an initial cohort of 165,621 patients in the UNOS database, we excluded 11,590 patients under 18 years of age, 5,457 patients listed status-1a, 3,778 patients who underwent repeat transplantation, and 223 patients who underwent multi-organ transplantation, aside from SLKT transplantation. A total of 6,452 patients with ACLF-3 at the time of waitlist registration were identified, of whom 3,925 (60.8%) underwent LT and 2,256 (35.0%) died or were removed for being too sick for transplantation. The remaining 4.2% of patients were removed for other reasons (Fig. S1). Of the patients who were transplanted, 3,636 (92.6%) underwent LT within 28 days of listing, of whom 2,744 (75.5%) patients remained at ACLF-3 and 892 (24.5%) improved to ACLF 0–2 at the time of LT.

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the study population. In column 1, we display characteristics at waitlist registration, whereas in columns 2 and 3 we depict both recipient and donor traits at transplantation, among those transplanted within 28 days of listing. At the time of waitlist registration, the mean age of our population was 51.8 years; the population was predominantly male (61.9%) and Caucasian (64.6%). The most common etiologies of cirrhosis were ALD (28.8%) and HCV infection (25.9%). The median model for end-stage liver disease-sodium (MELD-Na) score was 39.5. Liver failure (80.9%) and renal failure (80.6) were the most prevalent organ failures at waitlist registration, and the majority of patients had 3 organ failures (68.9%) as opposed to 4 or more organ failures (31.1%).

Table 1.

Recipient and donor characteristics at the time of listing and transplantation within 28 days of listing, among patients with ACLF-3 at registration.

| Recipient characteristics | ACLF–3 at listing (n = 6,452) | ACLF 0–2 at LT (n = 892) | ACLF–3 at LT (n = 2,744) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 51.8 (10.7) | 51.8 (10.3) | 51.3 (10.6) | 0.184 |

| Male, n (%) | 3,979 (61.9) | 548 (61.4) | 1,759 (64.1) | 0.130 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 1,473 (23.4) | 193 (21.9) | 611 (22.7) | 0.893 |

| Race/ethnicity: | 0.062 | |||

| Caucasian, n (%) | 4,167 (64.6) | 598 (67.0) | 1,745 (63.6) | |

| African-American, n (%) | 773 (11.9) | 105 (11.8) | 341 (12.4) | |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 1,093 (16.9) | 144 (16.1) | 475 (17.3) | |

| Etiology, n (%) | 0.036 | |||

| HCV | 1,675 (25.9) | 230 (25.8) | 699 (25.5) | |

| NASH | 775 (12.0) | 105 (11.8) | 341 (12.4) | |

| ALD | 1,861 (28.8) | 281 (31.5) | 906 (33.0) | |

| HBV | 310 (4.8) | 38 (4.3) | 163 (5.9) | |

| Cholestatic liver disease | 586 (9.1) | 101 (11.2) | 226 (8.2) | |

| HCC | 29 (0.31) | |||

| MELD-Na score, median (IQR) | 39.5 (35.1–43.2) | 34.3 (29.7–38.2) | 40.9 (36.9–44.3) | <0.001 |

| MELD exception | 32 (3.6) | 40 (1.5) | ||

| Albumin g/dl, median (IQR) | 3 (2.5–3.6) | 3.0 (2.5–3.5) | 3.1 (2.5–3.6) | 0.089 |

| Liver failure, n (%) | 5,198 (80.9) | 547 (61.7) | 2,458 (89.6) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 2,575 (39.9) | 20 (2.2) | 1,085 (39.5) | <0.001 |

| Circulatory failure, n (%) | 2,974 (46.1) | 55 (6.2) | 1,469 (53.5) | <0.001 |

| Coagulation failure, n (%) | 4,119 (64.1) | 254 (28.8) | 1,762 (64.2) | <0.001 |

| Brain failure, n (%) | 3,382 (52.4) | 166 (18.6) | 1,528 (55.6) | <0.001 |

| Renal failure, n (%) | 5,196 (80.6) | 460 (51.8) | 2,339 (85.3) | <0.001 |

| Number of organ failures, n (%) | ||||

| Three | 4,450 (68.9) | 1,248 (45.6) | ||

| Four-Six | 2,002 (31.1) | 1,496 (54.5) | ||

| Liver-kidney transplant | 123 (13.8) | 383 (13.9) | 0.899 | |

| Days before transplant | 6 (3–11) | 5 (2–9) | <0.001 | |

| Donor characteristics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 37.8 (15.2) | 37.8 (14.9) | 0.924 | |

| Donor risk index ≥1.7, n (%) | 170 (19.1) | 551 (20.1) | 0.506 |

ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure; ALD, alcohol-related liver disease; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; MELD-Na, MELD-sodium; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

Evaluation of differences between ACLF categories at the time of transplantation, using Student’s t test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and Chi-square testing.

Additionally, in Table 1, we compare the patient and donor characteristics at the time of LT, between patients with ACLF-3 at listing and transplantation and patients with ACLF-3 at listing who improved to ACLF 0–2 at transplantation. The 2 groups were similar in age, gender, ethnicity, donor age, and donor risk index (DRI). Regarding etiology of liver disease, the prevalence of ALD, HCV infection, and NASH were similar. As expected, median MELD-Na score was greater among recipients with ACLF-3 compared to ACLF 0–2 at the time of LT (40.9 vs. 34.3, p <0.001). With regards to particular organ failures at LT, liver (61.7%) and renal failure (51.8%) were the 2 most prevalent among patients who improved to ACLF 0–2 at transplant, whereas circulatory failure (6.2%) and mechanical ventilation (2.2%) were the least prevalent.

Table S2 describes the patient characteristics at the time of transplantation of the control group, which is comprised of the patients initially listed with ACLF 0–2 subdivided into those who remained as ACLF 0–2 (n = 17,631) and those who progressed to ACLF-3 (n = 2,265) at the time of LT.

One-year post-LT survival

Fig. 1 depicts patient survival probability 1 year after transplantation. For this analysis, we evaluated 4 patient groups: those who were downgraded from ACLF-3 at listing to ACLF 0–2 at LT, those who remained at ACLF-3 at listing and LT, those who had ACLF 0–2 at both listing and LT, and those with ACLF 0–2 at listing who progressed to ACLF-3 at LT. The 1-year post-transplant survival probability was significantly higher in patients listed with ACLF-3 who recovered from an organ failure(s) (88.2%) compared to those who did not (82.0%) (p <0.001). Our analysis further demonstrates no significant differences in patient survival among those who did not have ACLF-3 at either listing or transplantation (90.2%) and those who improved from ACLF-3 to ACLF 0–2 (88.2%) (p = 0.062). Additionally, patients who were listed at ACLF 0–2 and progressed to ACLF-3 at transplantation had lower survival (83.8%) compared to those with ACLF-3 who were downgraded to ACLF 0–2 (88.2%) (p <0.001).

Fig. 1. One-year post-transplant survival of patients with ACLF 0–2 or ACLF-3 at listing and LT.

*p value comparing survival probability with that of patients with ACLF-3 at listing and ACLF 0–2 at LT. ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure; LT, liver transplantation. Survival probability tested using Kaplan-Meier methods with log-rank testing.

We performed further survival analysis by subdividing patients with ACLF-3, according to whether they had 3 organ failures or 4 or more organ failures, as displayed in Fig. S2. Patients who had 3 organ failures at listing and LT had significantly higher 1-year post-transplant survival (85.3%) compared to individuals listed with 3 organ failures who progressed to 4–6 organ failures at transplantation (82.4%) and recipients listed with 4–6 organ failures who improved to 3 organ failures at LT (81.9%). As expected, patients with 4–6 organ failures at listing and transplantation had the lowest 1-year survival probability (76%).

Of the 3,636 ACLF-3 patients at the time of listing who were transplanted within 28 days of waitlist registration, 643 (17.7%) died within 1 year and 2,993 (82.3%) survived. Table 2 compares the population characteristics between those who died and survived at 1-year post-LT. The 2 groups were similar regarding gender, ethnicity, and median MELD-Na score. Patients who survived at 1 year were younger (50.8 vs. 53.7 years, p <0.001) and had a greater prevalence of ALD (34.5%) versus those who died (24.1%) (p <0.001). The percentage of patients with DRI ≥1.7 was also lower among those who survived (18.9%) versus those who died (24.3%) within 1 year of transplantation (p = 0.002).

Table 2.

Characteristics at time of transplantation comparing patients who survived or died at 1-year after LT, among patients listed with ACLF-3 and transplanted within 28 days.*

| Survived (n = 2,993) | Died (n = 643) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 50.8 (10.6) | 53.7 (10.2) | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 3,979 (61.9) | 548 (61.4) | 0.368 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 616 (20.9) | 188 (29.7) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity: | 0.077 | ||

| Caucasian, n (%) | 1,936 (64.7) | 407 (63.3) | |

| African-American, n (%) | 351 (11.7) | 96 (14.9) | |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 512 (17.1) | 107 (16.6) | |

| Etiology, n (%) | |||

| HCV | 745 (24.9) | 184 (28.6) | 0.171 |

| NASH | 377 (12.6) | 69 (10.7) | 0.191 |

| ALD | 1,032 (34.5) | 155 (24.1) | <0.001 |

| HBV | 171 (5.7) | 30 (4.7) | 0.282 |

| MELD-Na score, median (IQR) | 39.8 (34.9–43.2) | 39.0 (34.4–43.1) | 0.078 |

| Days before transplant | 5 (3–9) | 5 (3–10) | 0.653 |

| Improvement from ACLF-3, n (%) | 777 (25.9) | 115 (17.8) | <0.001 |

| Liver failure, n (%) | 2,467 (82.6) | 538 (83.8) | 0.461 |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 818 (27.3) | 287 (44.6) | <0.001 |

| Circulatory failure, n (%) | 1,176 (39.3) | 348 (54.2) | <0.001 |

| Coagulation failure, n (%) | 1,698 (56.7) | 318 (49.5) | 0.001 |

| Brain failure, n (%) | 1,355 (45.3) | 339 (52.7) | 0.001 |

| Renal failure, n (%) | 2,303 (77.1) | 496 (77.5) | 0.805 |

| Donor risk index ≥1.7 | 565 (18.9) | 156 (24.3) | 0.002 |

ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure; ALD, alcohol-related liver disease; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LT, liver transplantation; MELD-Na, model for end-stage liver disease-sodium; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

Evaluation of differences between ACLF categories at the time of transplantation, using Student’s t test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and Chi-square testing.

Additionally, there was a greater percentage of improvement from ACLF-3 at listing among those alive at 1 year (25.9%) compared to those who died (17.8%) (p <0.001). In our examination of specific organ failures at LT, it is notable that the prevalence of liver failure and renal failure were similar between the 2 groups, and the prevalence of coagulation failure was in fact greater among those alive (56.7%) compared to those who died (49.5%) before 1-year post-LT (p = 0.001). The requirement for mechanical ventilation (p <0.001), and the prevalence of circulatory failure (p <0.001) and brain failure (p = 0.001) were significantly higher among patients who died 1-year post LT.

Multivariable models and sensitivity analyses

In Table 3, we provide univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis to determine factors associated with mortality at 1 year after LT. Univariable analysis demonstrated that improvement in ACLF from grade 3 to grades 0–2 yielded a hazard ratio (HR) for 1-year mortality of 0.74 (95% CI 0.63–0.88). In our multivariable model, after adjustment for age, MELD-Na score, diabetes, and DRI, we found that downgrading of ACLF-3 was associated with a significant reduction in likelihood of 1-year post-LT mortality (HR 0.65; 95% CI 0.53–0.78). On multivariable analysis, additional factors found to be associated with mortality at 1 year after LT included age >60 years (HR 1.68; 95% CI 1.31–2.18), and DRI ≥1.7 (HR 1.22; 95% CI 1.03–1.45).

Table 3.

Cox regression models to predict 1-year post-transplant mortality.

| Reference | Hazard ratio, 95% CI* | Hazard ratio, 95% CI** | Hazard ratio, 95% CI*** | Hazard ratio, 95% CI**** | Hazard ratio, 95% CI† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACLF grade 0–2 at LT | ACLF grade 3 at LT | 0.74 (0.63–0.88) | 0.65 (0.53–0.78) | 0.65 (0.54–0.79) | 0.67 (0.55–0.81) | 0.63 (0.52–0.78) |

| Age 40–60 | Age <40 | 1.14 (0.92–1.42) | 1.13 (0.91–1.42) | 1.13 (0.89–1.43) | 1.12 (0.88–1.43) | |

| Age >60 | 1.70 (1.33–2.16) | 1.68 (1.31–2.18) | 1.74 (1.33–2.27) | 1.74 (1.32–2.28) | ||

| Age | 1.02 (1.01–1.02) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | ||||

| MELD-Na score | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | 0.97 (0.96–1.00) | 0.98 (0.97–1.00) | 0.97 (0.98–1.00) | 0.97 (0.96–1.01) | |

| ALD | NASH | 0.91 (0.78–1.05) | ||||

| Diabetic | Non-diabetic | 1.26 (1.07–1.48) | 1.18 (1.00–1.39) | 1.18 (1.00–1.39) | 1.10 (0.92–1.33) | 1.17 (0.98–1.42) |

| DRI ≥1.7 | DRI <1.7 | 1.24 (1.05–1.46) | 1.22 (1.03–1.45) | 1.22 (1.03–1.45) | 1.18 (0.98–1.42) | 1.14 (0.94–1.39) |

| Time to LT (days) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | |||||

| Years 2012–2017 | Years 2004–2011 | 0.88 (0.77–1.02) |

Univariable analysis.

Multivariable analysis.

Multivariable analysis, age as continuous variable.

Sensitivity analysis after removal of simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation (n = 506).

Sensitivity analysis after removal of HCV-infected patients (n = 1,089). ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure; ALD, alcohol-related liver disease; DRI, donor risk index; LT, liver transplantation; MELD-Na, model for end-stage liver disease-sodium; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

To assess the robustness of our findings, we performed 2 sensitivity analyses. The first was to rebuild our multivariable model after removal of patients who underwent SLKT transplantation (n = 506), since some of these recipients may have had chronic renal failure from non-hepatic comorbidities, as opposed to renal failure related to ACLF. In the second analysis we excluded HCV-infected recipients (n = 1,089), since post-LT survival has improved remarkably for HCV-infected recipients in the era of direct-acting antiviral therapy.17 Improvement from ACLF-3 to ACLF 0–2 at LT continued to be associated with reduced 1-year mortality after removal of SLKT recipients (HR 0.67; 95% CI 0.55–0.81) and HCV-infected patients (HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.52–0.78). (Table 3)

Specific organ failures

Table S3 compares 1-year mortality after LT among patients with ACLF-3 at listing, according to the presence or absence of specific organ failures at transplantation. We created 4 categories for this table: patients where the organ failure was not present at either listing or LT, patients where the organ failure was present at listing but recovered at LT, patients where the organ failure was not present at listing but was present at LT, and patients where the organ failure was present at both listing and LT. With regards to the presence or absence of liver or renal failure, similar mortality was found across all patient categories. However, mortality was significantly lower in patients who did not require mechanical ventilation (p <0.001) at transplantation; mortality was also lower for those without circulatory failure (p <0.001) or brain failure (p = 0.002) at LT than in recipients with either of these organ failures at transplantation. Notably, recipients who had coagulation failure at waitlist registration exhibited lower post-LT mortality compared to those in whom coagulation failure was not present at listing. As further analysis demonstrated a significantly shorter time to transplantation among those listed with ACLF-3 with coagulation failure versus those without coagulation failure (Table S4), we suspect this may be related to having a greater priority for transplantation due to higher MELD-Na scores.

In Table 4, we display our Cox proportional hazards regression models evaluating whether improvement in specific organ failures affects post-LT survival. Univariable analysis revealed that recovery from liver failure, renal failure, or coagulation failure was not associated with a lower likelihood of post-LT mortality, whereas an association with reduced mortality was noted for patients who were removed from mechanical ventilation (HR 0.55; 95% CI 0.42–0.71), or experienced a recovery from circulatory failure (HR 0.57; 95% CI 0.44–0.74) or brain failure (0.79; 95% CI 0.63–0.99). We then performed multivariable regression for each organ failure adjusting for age, MELD-Na score and DRI, which were selected a priori. Due to the likelihood of collinearity, we assessed each organ failure individually rather than incorporating all 6 organ failures into 1 model. We demonstrated that removal from mechanical ventilation (HR 0.55; 95% CI 0.42–0.71), and recovery from circulatory failure (HR 0.57; 95% CI 0.43–0.75) or brain failure (HR 0.76; 96% CI 0.60–0.97) were associated with a reduction in post-LT mortality.

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression evaluating impact of recovery from specific organ failures on mortality within 1 year of LT.

| Reference | Hazard ratio, 95% CI* | Hazard ratio, 95% CI** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No liver failure at LT | Liver failure at LT | 0.93 (0.67–1.27) | 0.84 (0.61–1.19) |

| No mechanical ventilation at LT | Mechanical ventilation at LT | 0.55 (0.42–0.71) | 0.55 (0.42–0.71) |

| No circulatory failure at LT | Circulatory failure at LT | 0.57 (0.44–0.74) | 0.57 (0.43–0.75) |

| No brain failure at LT | Brain failure at LT | 0.79 (0.63–0.99) | 0.76 (0.60–0.97) |

| No renal failure at LT | Renal failure at LT | 1.08 (0.86–1.35) | 0.99 (0.76–1.28) |

| No coagulation failure at LT | Coagulation failure at LT | 1.02 (0.84–1.24) | 1.05 (0.84–1.31) |

DRI, donor risk index; LT, liver transplantation; MELD-Na, model for end-stage liver disease-sodium.

Univariable analysis

Multivariable analysis adjusting for age, MELD-Na score and DRI.

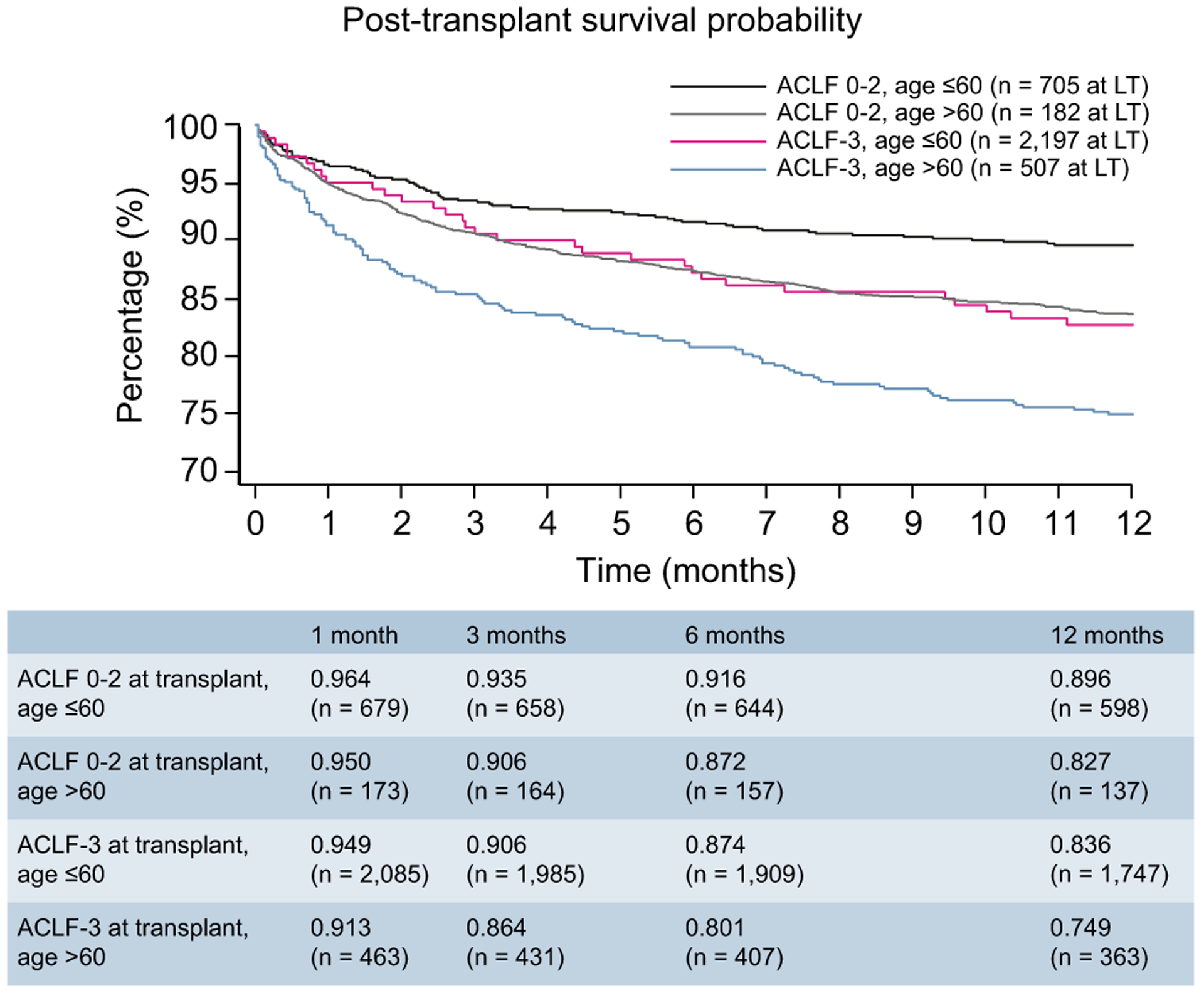

Impact of recipient age

Concurrent with the aging of the population of the United States, there has been a more than doubling in the number of patients aged >60 years who are listed for LT.18 Furthermore, recipient age >60 has previously been demonstrated to be a risk factor for death after LT.19,20 Therefore, we performed further investigation to determine whether recipient age >60 years influenced post-transplant outcomes in the setting of organ failure improvement. Fig. 2 depicts the survival probabilities of 4 patient groups: those who were downgraded to ACLF 0–2 at LT and were aged ≤60; those who were downgraded and aged >60; those with ACLF-3 at the time of LT who were aged ≤60; those with ACLF-3 at LT who were aged >60. One-year post-LT survival probability was greatest among recipients aged ≤60 who were transplanted with ACLF 0–2 (89.6%) (p <0.001). Survival rates were numerically similar between patients aged >60 with ACLF 0–2 (82.7%) and those aged ≤60 with ACLF-3 (83.6%). The lowest post-transplant survival probability was found among those aged >60 years with ACLF-3 (74.9%).

Fig. 2. One-year post-transplant survival of patients with ACLF-3 at listing, categorized by age and ACLF grade at transplantation (p <0.001).

ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure.

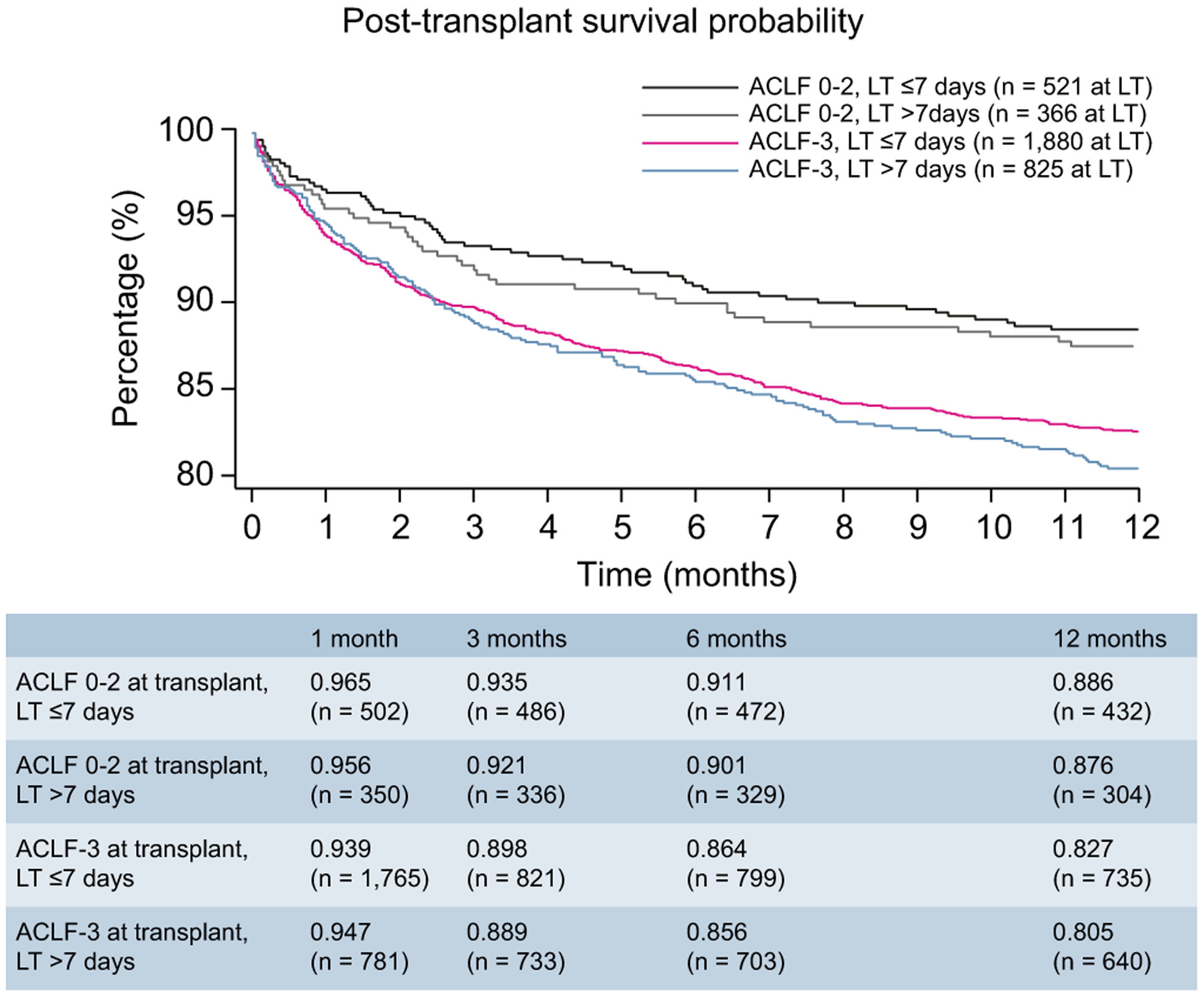

Timing of transplantation

We additionally evaluated whether the timing of transplantation affects post-LT survival outcomes. In Fig. 3, we provide survival analysis of 4 patient groups: those who were downgraded and transplanted within 7 days of listing, those who were downgraded and transplanted between 8–28 days of listing, those not downgraded but transplanted within 7 days of listing, and those not downgraded and transplanted between 8–28-days of listing. Our decision to utilize a timeframe of 7 days to categorize early versus late transplantation was based upon a prior study that demonstrated short-term prognosis without transplantation was determined based on grade of ACLF by day 7 after initial presentation.12 Therefore, our goal was to assess the impact of LT relative to when the patient developed their final ACLF grade.

Fig. 3. One-year post-transplant survival of patients with ACLF-3 at listing, categorized by timing of transplantation and ACLF grade at transplantation.

ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure.

Among patients who were downgraded from ACLF-3 prior to LT, 1-year survival is similar between those undergoing LT within 7 days (88.6%) and between 8–28 days (87.6%) (p = 0.252). However, for recipients with ACLF-3 at transplantation, there was a better survival when transplanted within 7 days (82.7%) versus after 7 days (80.5%) (p = 0.011). However, as shown in Table 3, timing of LT within the first 28 days after wait listing was not statistically significant when days to LT was analyzed as a continuous variable. Given the poor survival probability among those transplanted with ACLF-3 and aged >60 years, we also performed a sensitivity analysis to assess if timing of transplantation affected post-LT survival among patients aged >60 years with ACLF-3. In this setting, we found a numerically greater 1-year survival probability among those transplanted within 7 days (76.1%) compared to those transplanted beyond 7 days (72.6%). However, as the proportional hazards assumption for this analysis was not met; a p value was not determined (Fig. S3).

Discussion

In our study of 3,636 patients listed for LT with ACLF-3 and transplanted within 28 days, we demonstrate that improvement from ACLF-3 at listing to ACLF 0–2 at transplantation yields an excellent 1-year survival probability, particularly among recipients aged ≤60. Conversely, in patients that were listed with ACLF 0–2, the 1-year post-LT survival was significantly reduced if they advanced to ACLF-3 at transplantation. Taken together these findings demonstrate that ACLF is a dynamic syndrome that not only affects transplant-free survival12 but also post-transplant survival. Additionally, our study is the first to offer insight regarding which type of organ failure recovery yields the greatest likelihood for improved post-LT survival and the influence of patient age on post-LT outcomes, in the setting of multi-organ failure.

We believe these data have meaningful clinical implications. Although it is well established that LT yields survival benefit compared to supportive care in those with severe ACLF,10–12 certain centers, particularly those with smaller volumes, may handle transplantation of such patients with caution due to regulatory expectations of a 1-year post-transplant survival of 90%. However, our study findings indicate this target can be achieved even in the sickest patients, when recovery of organ function has been accomplished. The data support the view that it is reasonable to provide full supportive care and find a window for transplantation in the patient with ACLF-3, who may otherwise not be considered a suitable candidate for referral to a transplant center, due to being deemed “too sick for transplantation.” Greater awareness of our findings will reduce the likelihood of this scenario.

As ACLF is a heterogenous condition, it is important to assess the impact of the type of organ failure that has recovered, in addition to the number of organ failures that improved. Our study is the first to highlight that in patients listed with ACLF-3, improvement in mechanical ventilation status, circulatory failure, and brain failure are associated with a reduction in post-LT mortality. This may be explained by prior findings that showed that extrahepatic organ failures are associated with lower transplant-free survival than intrahepatic organ failures2 and that extrahepatic organ failures, including brain failure,21 may not be fully treated by replacement of the liver. Additionally, although persistent renal failure after LT can be treated with dialysis, there are no long-term extra-corporeal support mechanisms for mechanical ventilation, circulatory failure or brain failure. These results underscore the importance of additional strategies for the management of patient with ACLF, particularly regarding the circulatory and respiratory failure in this population.22 The findings, however, do not support denying LT for patients with ACLF-3 based on the presence of respiratory, brain or circulatory failure at LT, since post-LT survival is still considerably greater than transplant-free survival.10,11 Instead, we emphasize that the decision regarding transplantation and its timing should be made on a case-by-case basis depending on a variety of factors including the presence of certain organ failures.

As society continues to age, the prevalence of elderly patients with end-stage liver disease requiring transplantation has risen.18,23,24 Subsequently, the transplant community will increasingly need to decide whether LT of an elderly patient may be futile in the setting of multiple organ system failures.20 Our analysis regarding recipient age revealed that transplantation of a patient with ACLF-3 aged >60 yields poor post-LT survival probability, below 75%. This finding is consistent with prior data that has shown lower post-LT survival in patients >60 years old,25,26 particularly in combination with renal failure or mechanical ventilation.19 Although 1-year survival improves substantially in recipients aged >60 after downgrading of ACLF-3 to ACLF 0–2, the survival probability of 82.7% may still not be considered adequate by certain transplant centers. Subsequently, additional investigation is warranted regarding optimizing pre-transplant and post-transplant management in this population. In particular, the elderly population is at higher risk of being frail and sarcopenic, which have previously been demonstrated to affect both waitlist and post-transplant outcomes.27,28 Although we were unable to explore how sarcopenia and frailty effect mortality after LT in the setting of multi-organ failure, prospective research in this area would be highly beneficial. In the context of our study, these findings suggest that LT in patients with ACLF-3 who are >60 years old should perhaps only be considered after organ failure recovery, with the exception of those who are ‘biologically younger’.

We also investigated whether the timing of LT after improvement in ACLF-3 affects post-LT survival. ACLF is a dynamic condition and therefore determining the time period in which transplantation is successful may be challenging. It appears that the timing of transplantation within 28-days does not affect outcomes as long as there is a decrease in ACLF grade at LT, as we demonstrate only a 1% survival difference between those transplanted within 7 days (88.6%) and from 8–28-days (87.6%) from listing. Though these results appear to be contradictory to previous findings that indicated a reduction in mortality with LT within 30 days of listing 11, there are important distinctions between that study and the current one. First, in the current study all patients underwent LT within 28 days of listing, whereas the previous study did not have a limit on waiting time until transplantation. Second, our study evaluated outcomes among those who had improved from ACLF-3 at the time of LT, while the prior study assessed outcomes specifically in patients with ACLF-3 at transplantation.

The UNOS registry has certain advantages for this investigation, particularly the availability of a large sample size of patients with ACLF-3, across multiple regions in the United States. However, several limitations that are inherent in retrospective studies analyzing large public databases also exist in our study. First, there is the potential for misclassification. For instance, it is possible that certain individuals were incorrectly classified as not having ACLF-3 though they had a decompensating event such as variceal bleeding or bacterial infection, which are not captured in the UNOS database. Similarly, misclassification may also occur regarding grade of hepatic encephalopathy, as this is reported based on the subjective assessment of the treating provider.

Secondly, the study utilizes the presence of mechanical ventilation as an indicator for respiratory failure as the indication for mechanical ventilation is not available. Some patients may have been ventilated for airway protection due to altered mental status, whereas other patients with significant lung injury that qualifies as respiratory failure may not have been intubated at the time of liver transplantation. Similarly, administration of vasopressor support was used to identify patients with circulatory failure. However, certain patients requiring vasopressors may not have circulatory failure, such as the individual treated with norepinephrine for hepatorenal syndrome. Therefore, we suggest only applying our findings for respiratory or circulatory failure to patients who are ventilator- or vasopressor-dependent, respectively. Thirdly, information regarding organ failures is available only at the time of listing or transplantation, and we do not have data concerning the changes in the severity of ACLF in between those time points. Finally, the majority of patients studied had ALD, and a registry-based study cannot account for the occurrence of alcohol relapse after LT as a cause of 1-year patient mortality. However, we do not believe these limitations affect our conclusions, as our study focused on whether organ recovery at the time of LT improves post-LT survival. These limitations do however, prevent us from being able to develop a new scoring system to identify those at the highest risk of death on the waiting list and those at the highest risk of dying post-LT for which more granular, prospectively collected data are needed.

In summary, our study found that patients with ACLF-3 at waitlist registration who improve to ACLF 0–2 at transplantation have a greater than 88% post-LT survival at 1-year. Given the potentially high post-LT survival, consideration for transplantation should be given to patients with 3 or more organ failures, with a goal of performing LT during a window of organ failure recovery. In patients aged >60 years with ACLF-3, post-LT survival at 1 year may be poor (74.9%) and therefore it would be better to transplant these individuals after improvement of organ failures. Although recovery from circulatory failure and brain failure, and removal from mechanical ventilation appear to have the greatest impact on reducing post-LT mortality, the decision to proceed with transplantation should be made on a case-by-case basis. Prospective studies are needed to define prognostic scores for identifying those in whom urgent transplantation would be most beneficial versus those in whom LT would be futile, after accounting for a variety of factors including number and type of organ systems which have recovered, type of donor organ available, timing of transplantation, and patient age.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Improvement of ACLF-3 prior to transplantation improves the probability of 1-year post-LT survival from 82.0% to 88.2%

Patients aged >60 years have a post-LT survival probability of 74.9% if transplanted with ACLF-3.

This post-LT survival probability rises to 82.7% if patients are transplanted with ACLF 0–2.

Improvement in brain and circulatory failure and removal from mechanical ventilation are associated with post-LT survival.

Financial support

The authors received no financial support to produce this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ACLF

acute-on-chronic liver failure

- ALD

alcohol-related liver disease

- DRI

donor risk index

- HR

hazard ratio

- LT

liver transplantation

- NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- MELD

model for end-stage liver disease

- MELD-Na

MELD-sodium

- SLKT

simultaneous liver and kidney transplantation

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Rajiv Jalan has research collaborations with Yaqrit and Takeda. Rajiv Jalan is the inventor of OPA, which has been patented by UCL and licensed to Mallinckrodt Pharma. He is also the founder of Yaqrit limited, a spin out company from University College London. The other authors have nothing to disclose regarding conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.10.013.

References

- [1].Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, Pavesi M, Angeli P, Cordoba J, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1426–1437, 1437 e1421–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Shi Y, Yang Y, Hu Y, Wu W, Yang Q, Zheng M, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure precipitated by hepatic injury is distinct from that precipitated by extrahepatic insults. Hepatology 2015;62:232–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sundaram V, Jalan R, Ahn JC, Charlton MR, Goldberg DS, Karvellas CJ, et al. Class III obesity is a risk factor for the development of acute-on-chronic liver failure in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2018;69:617–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Arroyo V, Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, Study E-CCC. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: a new syndrome that will re-classify cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2015;62:S131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Arroyo V, Moreau R, Kamath PS, Jalan R, Gines P, Nevens F, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure in cirrhosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:16041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jalan R, Saliba F, Pavesi M, Amoros A, Moreau R, Gines P, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic score to predict mortality in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Hepatol 2014;61:1038–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sundaram V, Shah P, Wong RJ, Karvellas CJ, Fortune BE, Mahmud N, et al. Patients with acute on chronic liver failure grade 3 have greater 14-day waitlist mortality than status-1a patients. Hepatology 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Levesque E, Winter A, Noorah Z, Daures JP, Landais P, Feray C, et al. Impact of acute-on-chronic liver failure on 90-day mortality following a first liver transplantation. Liver Int 2017;37:684–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Umgelter A, Lange K, Kornberg A, Buchler P, Friess H, Schmid RM. Orthotopic liver transplantation in critically ill cirrhotic patients with multi-organ failure: a single-center experience. Transplant Proc 2011;43:3762–3768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Artru F, Louvet A, Ruiz I, Levesque E, Labreuche J, Ursic-Bedoya J, et al. Liver transplantation in the most severely ill cirrhotic patients: a multicenter study in acute-on-chronic liver failure grade 3. J Hepatol 2017;67:708–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sundaram V, Jalan R, Wu T, Volk ML, Asrani SK, Klein AS, et al. Factors associated with survival of patients with severe acute on chronic liver failure before and after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gustot T, Fernandez J, Garcia E, Morando F, Caraceni P, Alessandria C, et al. Clinical course of acute-on-chronic liver failure syndrome and effects on prognosis. Hepatology 2015;62:243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Huebener P, Sterneck MR, Bangert K, Drolz A, Lohse AW, Kluge S, et al. Stabilisation of acute-on-chronic liver failure patients before liver transplantation predicts post-transplant survival. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47:1502–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nadim MK, Sung RS, Davis CL, Andreoni KA, Biggins SW, Danovitch GM, et al. Simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation summit: current state and future directions. Am J Transplant 2012;12:2901–2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R, Perumpail RB, Harrison SA, Younossi ZM, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015;148:547–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cotter TG, Paul S, Sandikci B, Couri T, Bodzin AS, Little EC, et al. Increasing utilization and excellent initial outcomes following liver transplant of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-viremic donors into HCV-negative recipients: outcomes following liver transplant of HCV-viremic donors. Hepatology 2019;69:2381–2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Su F, Yu L, Berry K, Liou IW, Landis CS, Rayhill SC, et al. Aging of liver transplant registrants and recipients: trends and impact on waitlist outcomes, post-transplantation outcomes, and transplant-related survival benefit. Gastroenterology 2016;150, 441–53 e6; quiz e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Aloia TA, Knight R, Gaber AO, Ghobrial RM, Goss JA. Analysis of liver transplant outcomes for United Network for Organ Sharing recipients 60 years old or older identifies multiple model for end-stage liver disease-independent prognostic factors. Liver Transpl 2010;16:950–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Petrowsky H, Rana A, Kaldas FM, Sharma A, Hong JC, Agopian VG, et al. Liver transplantation in highest acuity recipients: identifying factors to avoid futility. Ann Surg 2014;259:1186–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dhar R, Young GB, Marotta P. Perioperative neurological complications after liver transplantation are best predicted by pre-transplant hepatic encephalopathy. Neurocrit Care 2008;8:253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Olson JC, Karvellas CJ. Critical care management of the patient with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplant in the intensive care unit. Liver Transpl 2017;23:1465–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ikegami T, Bekki Y, Imai D, Yoshizumi T, Ninomiya M, Hayashi H, et al. Clinical outcomes of living donor liver transplantation for patients 65 years old or older with preserved performance status. Liver Transpl 2014;20:408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wilson GC, Quillin RC 3rd, Wima K, Sutton JM, Hoehn RS, Hanseman DJ, et al. Is liver transplantation safe and effective in elderly (≥70 years) recipients? A case-controlled analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2014;16:1088–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Burroughs AK, Sabin CA, Rolles K, Delvart V, Karam V, Buckels J, et al. 3-month and 12-month mortality after first liver transplant in adults in Europe: predictive models for outcome. Lancet 2006;367:225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sharpton SR, Feng S, Hameed B, Yao F, Lai JC. Combined effects of recipient age and model for end-stage liver disease score on liver transplantation outcomes. Transplantation 2014;98:557–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lai JC, Segev DL, McCulloch CE, Covinsky KE, Dodge JL, Feng S. Physical frailty after liver transplantation. Am J Transplant 2018;18:1986–1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sundaram V, Lim J, Tholey DM, Iriana S, Kim I, Manne V, et al. The Braden Scale, A standard tool for assessing pressure ulcer risk, predicts early outcomes after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2017;23:1153–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.