Colombian Nobel prize awardee author Gabriel García Márquez, suffered cholera and many bouts of malaria during his life. In Love in the Time of Cholera, one of many masterpieces by him, he wrote that persistence (and handwashing!) were rewarded with love after a life of living with countless cholera outbreaks.

I am a respiratory epidemiologist; and literally, at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, we are now being bombarded with descriptive Epidemiology statistics and standard, cold figures: “As of today the death toll of COVID-19 worldwide is 114,290”; “The peak resource use of respirators and ICU rooms in the USA is expected on April 10, 2020…”, and counting. In the distant past, there have been devastating epidemics of infectious disease, such as cholera, the 1918 flu (wrongly called Spanish), the plague’s Black Death,… Other more recent outbreaks like SARS, MERS or Ebola were considered exotic, faraway occurrences.

Yet we were not ready for this one. And at the least for the last four generations, we are now living unprecedented times. No one, even in the wildest nightmares of any Hollywood-based science fiction screenwriter, would have anticipated that 2020 would have started with such drama and suffering. When we were raising our glasses and toasting on New Year’s Eve for a Happy 2020, few were aware of a safety alert reported that morning in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China due to a cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown etiology [1].

It took only 10 days, on January 9, 2020, for China’s CDC to report that a novel coronavirus was the causative agent of that local outbreak. As for good and for bad, all is globally interconnected, that minute incident in China is the reason why we live in lockdown, basic civil liberties are limited, many deaths and suffering, and locally my hospital being near collapse. Hospital de La Princesa, an old 450-bed, tertiary hospital in downtown Madrid, Spain, had its D Day on March 30, 2020, when a total 552 COVID-19 patients were admitted, and 120+ more patients were in the emergency room, impatiently waiting to be admitted [2]. Many two-patient rooms already had three, even four occupants. Our petite, modern ICU room with 17 beds had to be stretched to 73 beds, by invading two surgical theatres turned to critical care, as well as the entire Psychiatric ward. Mirroring ancient times, all mentally ill patients, including those with active, severe paranoid schizophrenia or major depression, were sent home with their relatives to make room for others requiring invasive mechanical ventilations, mostly with improvised ventilators, or by reusing disposable ones, or duplicating machines with home-made technology. Even friends who have been veteran volunteers with Médecins Sans Frontières in Syria’s civil war, or at Sierra Leone’s Ebola zone, were not ready. Using military terminology, La Princesa was a war-time hospital in the front line; my Respiratory department with thirteen staff plus eight residents, suffered eleven “casualties”, counting quarantines plus infections plus one admission with severe, bilateral pneumonia. But other Madrid hospitals were hit even harder; colleagues at Hospital La Paz or Gregorio Marañón, were suffering an even worse avalanche of patients to care for. All like a modern hecatombe, literally from the ancient Greek ἑκατόν, hekatón, “one hundred” and βοῦς, boũs, “ox”, a religious sacrifice of a hundred oxen to indicate a great catastrophe with great mortality, or the end of the world.

We are still facing a cruel disease and global epidemic, both of Biblical proportions [3]. It is still severely and seriously affecting our old ones and others with heart, lung and other chronic diseases. But not only them. Several colleagues of mine, young, completely healthy, even athletic, have been admitted into the same ward where the previous day they were seeing patients; two friends have been in the intensive care unit, with tracheostomies, fighting for their lives. Why? We still don’t know whether an immunological, genetic factor, a combination of risk factors, or serendipity make this little RNA virus collapse your bronchi and lungs with a thick “snail snot or slime” and accompanied with an inflammatory outburst killing some perfectly healthy lungs. As Dr Landete was explaining to junior residents in the morning clinical round: “-This is the first time that I have seen the occurrence of acute sudden respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in front of my eyes. In the emergency room I was examining a walk-in 52 yr-old, female patient with temperature, malaise and a dry cough, and within 20 min, I had to call an ENT colleague to intubate this patient, as she had developed the fastest, quickest ARDS I’ve ever seen”. Even after all their greatest efforts and in the best hands, they could not save her. It is indeed a nasty little bug [4].

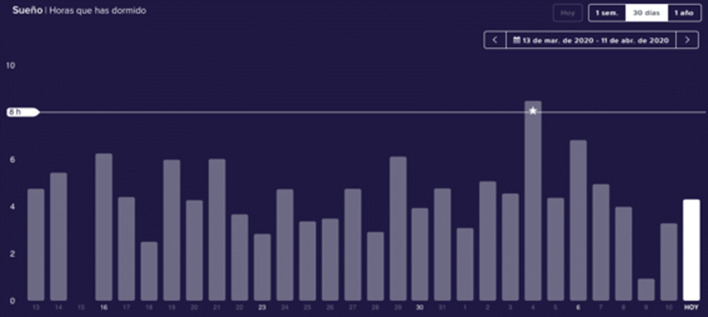

However, there is always hope, and as seen in great literature, times of crisis bring out the best in us. To date, I have seen residents choosing to stay longer after finishing a 24-h duty to try and save one more critically ill patient; auxiliary nurses improvising aprons and boots with trash bags, who, on finally receiving their space suits, posed for posterity like a football team, always with a ready smile (Fig. 1); residents in Neurology, Immunology or Pathology becoming Chest Medicine residents; medical students volunteering to learn the practicalities of lung mechanics and gas exchange; a Department Head creating a blog aimed at praising individuals for outstanding bravery and commitment; or I have been privileged to lead a small Think Tank including nurses, doctors, physicists, engineers and other friends who from Saturday March 14 have met on a daily basis to brainstorm initiatives by videoconference at 7 am, just before seeing patients or awakening their families. Many of the above have been living for 2 weeks in hotels next to our hospital, extremely and severely sleep deprived for a month already (Fig. 2). Our hospital administrators recommended all staff not to take weekends off until further notice. No one disagreed, trade unions included, out of a 2000+ headcount. And this has been going on for nearly a month. Again, all always with a ready smile. This is the so-called, Espíritu de La Princesa.

Fig. 1.

Auxiliary nurses in Hospital Universitario de La Princesa, April 9, 2020

Fig. 2.

Sleep frequency of a medical doctor during the COVID-19 outbreak in Hospital Universitario de La Princesa, March 13 to April 11, 2020, by Fitbit, with permission (https://www.fitbit.com/sleep)

Myself, a humble respiratory epidemiologist that has dedicated his professional life to research on COPD, asthma and tobacco had to go back to the textbooks and online resources for a fast-track, hands-on crash course on outbreaks research, counting the number of deaths, infected cases, R0 infectivity, and the like [5]. That was the easy part. Realizing that behind every case there was a personal tragedy, a family loss, slowly broke my heart and my lungs. So many people dying alone in elderly homes and residences, without medical care, without any care. I imagine not even anyone holding their hands. Calling for the sake of hygiene and competing priority, no one available to say a prayer while they were buried or cremated, alone. It will take time to accept this sad passing away, a cruel ending for many.

We must live in this planet, there is no other Earth or planet/plan B. And we have observed that air pollution and Planetary Health can be improved within weeks, with concerted individual and societal efforts [6]. Children confined at home for 3 weeks already, have appreciated playing with their brothers and sisters, or talking with neighbors across the balconies; even remotely with their school friends and teachers. They should be the first to end confinement. And we need to learn the lessons from history. This is not our first epidemic. It is the toll we have to pay for living in society and in cities. If we were still collectors and hunters in the wild, no such thing would have happened. Yet humans are emotional, social animals and beyond our species Homo sapiens, scholars say we are of emotionalis subspecies. As human animals we are not meant to live alone, or die alone, or in solitude.

I have no doubt that when this crisis is over, and I am positive it will be over soon, music, theatre, movies, literature and The Arts in general, will help to restore balance, and make us all wiser, better persons. The so-called move from omics to humanomics [7]. Beyond modern, ever more technical and robotized medicine, medical humanism in the twenty-first century is to be more important than ever [8].

As Pangloss, Candide’s optimistic teacher in Voltaire’s masterpiece, said: “Everything happens for a reason”. Pangloss chants over and over: “… all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds” while Candide leads an outrageous life illustrating that it is patently false. But we have no room for pessimism. I remember reading Essay on Blindness by the Portuguese author José Saramago; happily, the panic and selfishness in his outbreak of sudden blindness only occurred in his literature. Let’s only imagine if Gabo’s inspiration were by nowadays COVID-19 pandemic, and his Love in the Time of Cholera, were rewritten. Or La Peste by French novelist Albert Camus who, at the premature age of 46 died in a car accident near Sens. Camus, not wearing a safety belt in the passenger seat, died instantly. But, what a life! La Peste tells the story of a plague sweeping the French Algerian city of Oran. Nevertheless. it is not a medical book, but about human passions during and after an outbreak. Can’t wait to re-read it.

In all of these books, and other, health personnel have been rightfully characterized and praised as heroes and martyrs. Yet, last but certainly not least, I wish to make a call to remember the crucial role played by our non-health related hospital staff. Thoroughly well-deservedly nurses and doctors are credited since they must frequently and harshly endure the pains of COVID-19. However, their work would all be a lost effort without the cleaning personnel, wardens, cooks and cafeteria caterers, administrative workers, security forces, lab technicians, and other hospital-based job groups. They suffer this modern plague equally, often without protection, mostly without recognition, but always proudly; working 24/7, weekends included, and again always with a ready smile. These critical workers should be praised and acknowledged equally since, with no cleaners and cooks, our hospitals would instantly collapse.

As this is neither the last outbreak, and with all likelihood nor “the” last big one, we need to learn one more lesson from the past. In the future, let’s never again take for granted those simple things that during confinement we have suddenly seen as precious: a bear hug, a slap on the back and, of course, a ready smile without a face mask. I have no doubt that Medical Humanism and The Arts are already helping; and they will help us to learn to take better care of our patients, our loved ones, and ourselves.

JB Soriano, MD. Madrid, April 14, 2020.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest or competing interests to report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Emergencies preparedness, response. Pneumonia of unknown cause—China. https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/. Accessed 5 Jan 2020.

- 2.Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar. Situación de COVID-19 en España. https://covid19.isciii.es. Accessed 14 Apr 2020.

- 3.Horton R. Offline: COVID-19—what countries must do now. Lancet. 2020;395:1100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30787-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koo D, Thacker SB. In snow’s footsteps: commentary on shoe-leather and applied epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(6):737–739. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watts N, Amann M, Arnell N, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Belesova K, Boykoff M, Byass P, Cai W, Campbell-Lendrum D, Capstick S, Chambers J, Dalin C, Daly M, Dasandi N, Davies M, Drummond P, Dubrow R, Ebi KL, Eckelman M, Ekins P, Escobar LE, Fernandez Montoya L, Georgeson L, Graham H, Haggar P, Hamilton I, Hartinger S, Hess J, Kelman I, Kiesewetter G, Kjellstrom T, Kniveton D, Lemke B, Liu Y, Lott M, Lowe R, Sewe MO, Martinez-Urtaza J, Maslin M, McAllister L, McGushin A, Jankin Mikhaylov S, Milner J, Moradi-Lakeh M, Morrissey K, Murray K, Munzert S, Nilsson M, Neville T, Oreszczyn T, Owfi F, Pearman O, Pencheon D, Phung D, Pye S, Quinn R, Rabbaniha M, Robinson E, Rocklöv J, Semenza JC, Sherman J, Shumake-Guillemot J, Tabatabaei M, Taylor J, Trinanes J, Wilkinson P, Costello A, Gong P, Montgomery H. The 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate. Lancet. 2019;394(10211):1836–1878. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.FitzGerald JM, Poureslami I. The need for humanomics in the era of genomics and the challenge of chronic disease management. Chest. 2014;146(1):10–12. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McFarland J, Markovina I, Gibbs T. Opening editorial—the importance of the humanities in medical education. MedEdPublish. 2018;7:3. doi: 10.15694/mep.2018.0000140.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]