Abstract

Background:

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common heart rhythm disorder and is associated with a 5-fold increased risk of ischemic stroke. Racial/ethnic minorities and women with AF have higher rates of stroke compared to white individuals and men respectively. Oral anticoagulation reduces the risk of stroke, yet prior research has described racial/ethnic and sex-based variation in its use. We sought to examine the initiation of any oral anticoagulant (warfarin or direct-acting oral anticoagulants, DOACs) by race/ethnicity and sex in patients with incident, non-valvular AF. Further in those who initiated any anticoagulant, we examined DOAC vs. warfarin initiation by race/ethnicity and sex.

Methods:

We used claims data from a 5% sample of Medicare beneficiaries to identify patients with incident AF from 2012–2014, excluding those without continuous Medicare enrollment. We used logistic regression to assess the association between race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic), sex, and oral anticoagulant initiation (any, warfarin vs. DOAC), adjusting for sociodemographics, medical comorbidities, stroke and bleeding risk.

Results:

The cohort of 42,952 patients with AF included 17,935 women, 3282 blacks, and 1958 Hispanics. Overall OAC initiation was low (49.2% whites, 48.1% blacks, 47.5% Hispanics, 48.1% men, and 51.5% women). After adjusting, blacks (odds ratio (OR) 0.84; 95% CI, 0.78–0.91) were less likely than whites to initiate any oral anticoagulant with no difference observed between Hispanics and whites (OR 0.92; 95% CI, 0.83–1.01). Women were less likely than men to initiate any oral anticoagulant, OR 0.59 (95% CI 0.55–0.64). Among initiators of oral anticoagulation, DOAC use was low (35.8% whites, 29.3% blacks, 40.0% Hispanics, 41.6% men, and 42.4% women). After adjusting, blacks were less likely to initiate DOACs than whites, OR 0.75 (95% CI 0.66–0.85); the odds of DOAC initiation did not differ between Hispanic and white patients or between men and women.

Conclusion:

In a national cohort of Medicare beneficiaries with newly-diagnosed AF, overall oral anticoagulant initiation was lower in blacks and women, with no difference observed by Hispanic ethnicity. Among oral anticoagulant initiators, blacks were less likely to initiate novel DOACs, with no differences identified by Hispanic ethnicity or sex. Identifying modifiable causes of treatment disparities is needed to improve quality of care for all patients with AF.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation, race/ethnicity, gender, disparities

Introduction:

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common heart rhythm disorder worldwide, with over 5 million individuals diagnosed each year.1 AF is a leading cause of stroke, with an up to 5-fold increased risk of ischemic stroke observed in individuals with the condition.2 Notably, racial and ethnic minorities with AF have higher rates of AF-related complications compared to white patients, including nearly 1.5- times the risk of stroke.3 Whereas stroke risk is significantly reduced with oral anticoagulation,2 previous research has demonstrated racial and ethnic disparities in the quality and efficacy of traditional warfarin-based anticoagulation.4 Likewise, prior studies have shown that women with AF have higher rates of stroke than men, with sex-related differences in oral anticoagulant use and quality also reported.5 These disparities in anticoagulation have therefore been hypothesized as a possible mechanism by which AF-related complications persist.

In a recent update to AF management guidelines, leading cardiovascular society experts recommended direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) over warfarin for stroke prevention in eligible patients with AF.6 DOACs have been approved for stroke prevention in patients with AF since 2011 and recent evidence has demonstrated their improved efficacy, safety, and adherence compared to warfarin for stroke prevention.7,8 Nevertheless, little is known about real-world racial, ethnic, or sex-related differences in DOAC use for AF, and their potential to reduce disparities in AF-related outcomes.9 Thus, we aimed to compare warfarin and DOAC initiation by race, ethnicity, and sex in a national cohort of patients with incident, non-valvular AF. We hypothesized that racial and ethnic minorities and women would be less likely to receive novel DOACs compared to white and male patients respectively.

Methods:

Cohort Selection

We identified patients with incident AF between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2014 using 2012–2014 claims data from a 5% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries. We excluded patients without continuous Medicare Part D enrollment and using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Chronic Condition Data Warehouse indicator of AF, , we identified those with a diagnosis of AF.10 For these patients, we extracted all prescriptions filled for warfarin and DOACs (i.e., apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban) between the first AF diagnosis (index date) and December 31, 2014. This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh.

Outcomes and Covariates

The primary outcome was initiation of any oral anticoagulant (warfarin or DOAC) after the index AF diagnosis by race, ethnicity, and sex. Further, among oral anticoagulant initiators, we examined initiation of warfarin vs. DOAC by race, ethnicity, and sex. We recorded baseline patient-level demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics on the index diagnosis date. Demographic characteristics included age, sex, race and ethnicity — classified as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black (further referred to as white and black), and Hispanic, and geographic region. The socioeconomic factors examined were Medicaid eligibility and zip code-level median household income. Clinical characteristics included the risk of stroke as measured by CHA2DS2-VASc score [an index composed of points for congestive heart failure; hypertension; age ≥75 years; diabetes mellitus; prior stroke, transient ischemic attack, or thromboembolism; vascular disease; age 65–74 years; and sex category (female)]11 and the risk of bleeding as measured by HAS-BLED score [a score comprised of points for hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile international normalized ratio (INR), elderly (> 65 years), drugs/alcohol use concomitantly].12 We further included other clinical factors associated with oral anticoagulant use such as history of chronic kidney disease, a recent history of bleeding (defined as having a claim with diagnosis codes for bleeding events in the year before index date), and recent use of antiplatelets (defined as filling an antiplatelet prescription in the 6 months before index date).

Statistical Analysis

We compared baseline characteristics by sex, race, and ethnicity using analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. We used logistic regression to assess the association between race and ethnicity (white, black, and Hispanic), sex, and any oral anticoagulant initiation, adjusting for all previously described baseline covariates. We further used logistic regression to model the association between race and ethnicity, sex, and warfarin vs. DOAC initiation among oral anticoagulant initiators. White race and male sex served as the referent groups for race/ethnicity and sex respectively. Notably we examined the interaction between race and sex for both anticoagulant outcomes and it was not statistically significant; therefore, this term was not included in the logistic regression model. Our analyses excluded those in the study sample without a known race at baseline (n=1617; 3.8%). All analyses were conducted using commercially available statistical software (SAS 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results:

Among 42,952 patients with incident, non-valvular AF, 17,935 (41.8%) were women, 3,282 (7.6%) black, and 1,958 (4.6%) Hispanic (Table 1). Black patients were younger and had more individual comorbid conditions than white patients. Black and Hispanic patients were more likely to be eligible for Medicaid and had lower median household incomes than whites. Women were younger than men and had lower CHA2DS2VASc scores, otherwise there was variable distribution of comorbid conditions observed by sex.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries with Incident Atrial

Fibrillation Stratified by Sex, Race and Ethnicity

| Characteristics | Male (n=25,017) | Female (n=17,935) | Non-Hispanic White (n=35,886) | Non-Hispanic Black (n=3,423) | Hispanic (n=2,046) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD)*^ | 79.2 (10.0) | 74.3 (10.2) | 77.9 1 (10.0) | 73.8 (13.0) | 77.1 (11.1) |

| Medicaid eligibility (%)*^ | 32.5 | 25.3 | 22.8 | 63.5 | 69.7 |

| Median Household Income, by zip code, US Dollars* | 49,651 | 49,705 | 50,475 | 40,119 | 45,980 |

| Region (%)*^ | |||||

| Northeast | 21.4 | 20.7 | 21.7 | 17.9 | 19.1 |

| Midwest | 25.1 | 24.1 | 26.6 | 19.8 | 8.4 |

| South | 38.1 | 37.9 | 37.0 | 55.7 | 36.8 |

| West | 15.4 | 17.2 | 14.7 | 6.5 | 35.5 |

| Medical comorbidities (%)*^ | |||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 38.7 | 41.1 | 37.5 | 58.9 | 47.5 |

| Hypertension | 91.8 | 88.7 | 89.9 | 96.0 | 93.7 |

| Stroke | 20.5 | 25.4 | 22.5 | 30.9 | 26.5 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 8.5 | 10.0 | 9.2 | 9.4 | 8.7 |

| Congestive heart failure | 52.3 | 48.7 | 48.8 | 66.4 | 62.2 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 44.7 | 46.5 | 42.3 | 63.1 | 66.4 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score, mean (SD)*^+ | 5.3 (1.7) | 3.9 (1.7) | 4.7 (1.8) | 5.1 (2.0) | 5.1 (1.9) |

| HAS-BLED score, mean (SD)*^+ | 3.8 (1.0) | 3.6 (1.0) | 3.70 (1.0) | 3.9 (1.0) | 3.9 (1.0) |

| History of bleeding (%)*^ | 19.2 | 16.8 | 17.2 | 22.5 | 19.4 |

| Use of antiplatelet agents (%)*^ | 11.9 | 14.0 | 12.5 | 13.5 | 15.5 |

| Use of Anticoagulation (%) | 48.1 | 51.5 | 50.3 | 46.2 | 45.5 |

| Warfarin (%) | 51.9 | 48.5 | 57.1 | 70.7 | 60.0 |

| DOAC (%) | 41.6 | 42.4 | 42.9 | 29.3 | 40.0 |

The table shows selected patient characteristics. A full list of covariates included in adjusted regression models is provided in the Methods.

The sum of the sample sizes of the White, Black, and Hispanic groups does not add up to the totality of the study sample, because 1617 patients had missing information or Other listed for race and ethnicity.

represents significant differences by race/ethnicity.

represents significant differences by sex.

CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED as described in Methods section. Because Medicare claims do not contain INR, the HAS-BLED score was calculated as the sum of all factors comprising this score except the INR

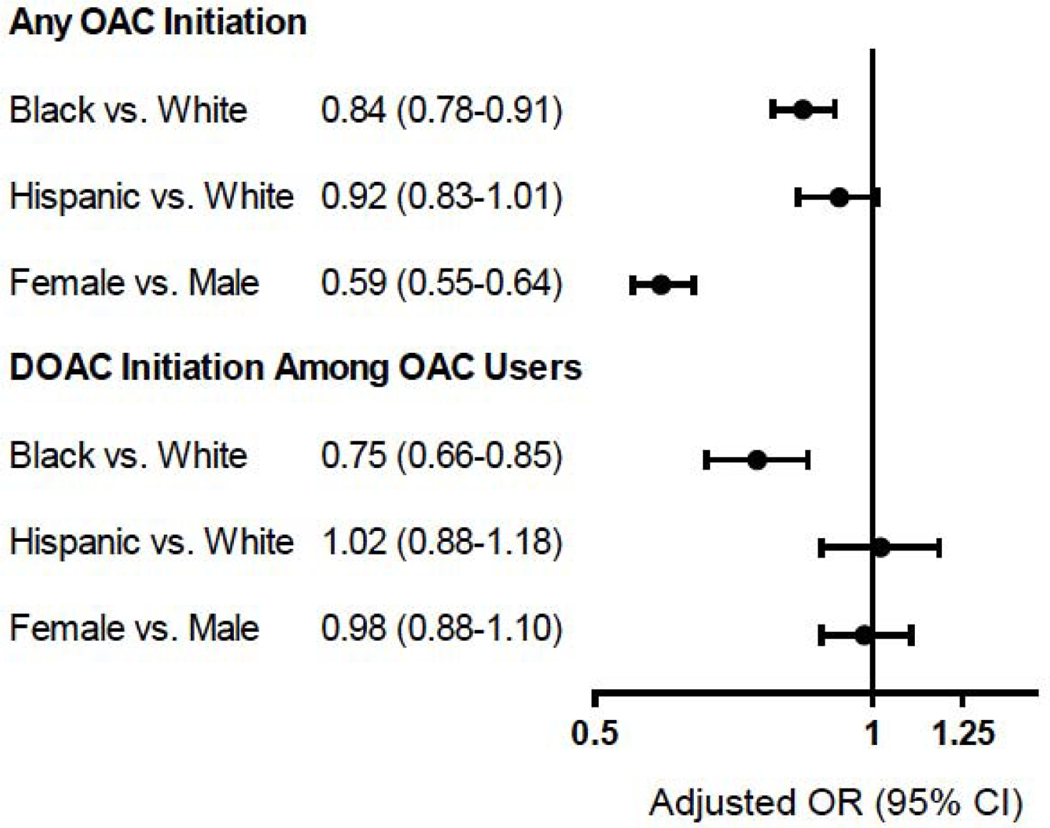

Overall oral anticoagulant initiation was low (49.5%) and presented small absolute differences by race and ethnicity (50.3% whites, 46.2% blacks, and 45.5% Hispanics) or sex (48.1% men and 51.5% women). Compared to white patients, black patients (adjusted Odds Ratio [aOR] 0.84; 95% CI, 0.78–0.91) had significantly lower adjusted odds of initiating any oral anticoagulant (Figure 1). There was no difference in oral anticoagulant initiation between Hispanic and white patients (aOR 0.92; 95% CI 0.82–1.01)., Women had significantly lower adjusted odds of initiating any oral anticoagulant than men (aOR 0.59; 95% CI, 0.55–0.64).

Figure 1. Adjusted Odds of any OAC and DOAC Use among OAC initiators by Sex, Race and Ethnicity.

The figure shows adjusted odds ratios for any OAC initiation and DOAC initiation among OAC users by race, ethnicity, and sex, adjusted for patient-level demographic, socioeconomic and clinical factors. Abbreviations: OAC=Oral Anticoagulation; DOAC=Direct Oral Anticoagulants; OR=Odds Ratio.

Among the 21,266 initiators of oral anticoagulation, 12,354 (58.1%) initiated warfarin and 8,912 (41.9%) initiated a DOAC. DOAC initiation differed more by race and ethnicity (42.9% whites, 29.4% blacks, and 40.0% Hispanics; p<0.01) than by sex (42.4% men and 41.6% women; p=0.88). Compared to white patients, blacks (aOR 0.75; 95% CI, 0.66–0.85) had significantly lower adjusted odds of initiating DOACs (Figure 1). Among oral anticoagulant initiators, the adjusted odds of initiating DOACs were not significantly different for Hispanic vs. white patients (aOR 1.02; 95% CI, 0.88–1.18) and women vs. men (aOR 0.98; 95% CI, 0.88–1.10). The results of the full logistic regression models by race, ethnicity, and sex can be found in Supplemental Tables S1 and S2 respectively.

Discussion:

In a national cohort of Medicare beneficiaries with incident, non-valvular AF, oral anticoagulant initiation was lower in blacks and women than in whites and men, respectively, with no difference observed between Hispanic and white individuals. Furthermore, among oral anticoagulant initiators, black patients had significantly lower adjusted odds of initiating DOACs, with no significant differences observed in DOAC initiation by Hispanic ethnicity or sex. Notably, the racial differences in anticoagulant initiation observed in this study persisted when controlling for socioeconomic status factors including Medicaid eligibility and median household income by zip code. These findings extend the current literature on disparities in cardiovascular disease prevention as they represent a real-world assessment of anticoagulant use in medically insured patients with newly-diagnosed AF and describe notable disparities in the use of novel stroke prevention therapies in this patient population.

Similar to previous studies, we demonstrated that racial and sex differences exist in oral anticoagulant use in patients with AF, particularly in the initiation of DOACs in black patients. A recent study using data from a large national registry of patients with AF, the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation II (ORBIT-AF II), showed that black patients had a 27% lower odds of receiving DOACs compared to white patients.9 This observed racial disparity in DOAC use was similar to that demonstrated in the present study, though patients in the ORBIT-AF II registry had far higher rates of overall oral anticoagulant use (84–89%). The higher rate of overall anticoagulant use observed in ORBIT-AF II has been reported in other AF clinical registries, including the Global Registry on Long-Term Oral Antithrombotic Treatment in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation, GLORIA-AF (80%)13 and the Get With The Guidelines-AF registry (96.6%),14 but is likely not representative of the general population of patients with AF. Similarly, clinical AF registries and trials may not fully illustrate racial differences in oral anticoagulation given their generally low rates of racial and ethnic minority enrollment.15 The findings from the current study therefore likely provide a more generalizable representation of the racial variation that exists in anticoagulant prescribing.

Using 2008–2014 data from the PINNACLE National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR), Thompson et al. found that women with AF (56.7%) were significantly less likely than men (61.3%) to use any oral anticoagulant, regardless of stroke risk.16 However, the NCDR study had a high rate of patients missing race/ethnicity (31%) and insurance status (21%) information, and the authors were otherwise limited in their ability to measure patient socioeconomic status. These important patient-level factors have been previously associated with oral anticoagulant initiation17 and are well captured in the present analysis.

Given the observational nature of our study, it is difficult to determine what mechanisms explain the racial/ethnic and sex-based disparities observed in our analysis. While prior studies have examined socioeconomic factors including insurance status and income as potential mediators of access to cardiovascular care, few have examined these factors as they relate to anticoagulant initiation, particularly DOACs.18 Although our study broadly controlled for these factors, a closer assessment of individual-level cost of AF care including out-of-pocket cost of oral anticoagulant prescriptions, and non-economic social factors such as health literacy and trust in the health care system, is warranted in future disparities research. Furthermore, it is essential to expand our understanding of how differences in provider factors such as specialty, clinical role (e.g. physician, nurse, or pharmacist) and implicit bias, as well as system-level factors including the presence of an anticoagulation clinic and generosity of medical insurance coverage for anticoagulant therapy may explain racial/ethnic and sex-based differences.

Our study has some limitations to acknowledge. First, although we adjusted for multiple patient demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors, our analyses used observational data that may still be subject to residual confounding by unmeasured patient-, provider-, or system-level factors. Second, we were unable to examine whether patients did not initiate oral anticoagulation because they were not prescribed or because they did not fill their prescriptions. Third, even though AF is more frequent in older adults, our findings are based on Medicare beneficiaries and consequently may not be generalizable to younger patient populations with AF, particularly to the uninsured or those with other forms of insurance where cost-related barriers to medication access may differ compared to Medicare. Similarly, we were unable to determine whether there were Medicare beneficiaries who did not qualify for Medicaid coverage yet were unable to afford enrollment in a Medicare Part D plan, potentially limiting initiation of higher cost DOACs in patients with low socioeconomic status. Fourth, because Medicare claims data only captures prescriptions paid for through Medicare Part D, our findings do not account for medications purchased with cash or medications purchased without a prescription (e.g. over-the-counter aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) which may influence the initiation of anticoagulation. Lastly, our data may not reflect temporal trends in OAC prescribing which likely have resulted in increased DOAC prescribing since the study period.

Implications:

Using data from a large cohort of Medicare beneficiaries with incident, non-valvular AF, we found that overall oral anticoagulant initiation was lower in black individuals and women compared to whites and men respectively, even when controlling for socioeconomic differences. We also identified racial differences in DOAC use, with black patients less likely to initiate DOACs – shown to be easier to use, safer, and more effective than warfarin in stroke prevention. These findings add to the existing body of literature demonstrating racial, ethnic, and sex-based disparities in oral anticoagulant use for AF, particularly in the early adoption of novel DOACs in these vulnerable patient populations. Efforts to improve the processes and outcomes of care for patients with AF should address existing inequities in the use of evidence-based treatment for this increasingly prevalent condition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (grant number K01HL142847).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Utibe R. Essien, Division of General Internal Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania..

Jared W. Magnani, Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Heart and Vascular Institute, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania..

Nemin Chen, Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania..

Walid F. Gellad, Division of General Internal Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania..

Michael J. Fine, Division of General Internal Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania..

Inmaculada Hernandez, Department of Pharmacy and Therapeutics, University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania..

References:

- 1.Chugh SS, Havmoeller R, Narayanan K, et al. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: A global burden of disease 2010 study. Circulation. 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf PA, Dawber TR, Thomas HE, Kannel WB. Epidemiologic assessment of chronic atrial fibrillation and risk of stroke: The fiamingham Study. Neurology. 1978;28(10):973–973. doi: 10.1212/WNL.28.10.973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magnani JW, Norby FL, Agarwal SK, et al. Racial Differences in Atrial Fibrillation-Related Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(4):433–441. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golwala H, Jackson LR, Simon DN, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in atrial fibrillation symptoms, treatment patterns, and outcomes: Insights from Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment for Atrial Fibrillation Registry. Am Heart J. 2016;174:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan RM, Zhang J, Zamba G, Lip GYH, Olshansky B. Relation of gender-specific risk of ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation to differences in warfarin anticoagulation control (from affirm). In: American Journal of Cardiology. Vol 110 ; 2012:1799–1802. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heidenreich PA, Furie KL, Shea JB, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation. 2019. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000665 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xian Y, Xu H, O’Brien EC, et al. Clinical Effectiveness of Direct Oral Anticoagulants vs Warfarin in Older Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and Ischemic Stroke. JAMA Neurol. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernandez I, Zhang Y, Saba S. Comparison of the Effectiveness and Safety of Apixaban, Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban, and Warfarin in Newly Diagnosed Atrial Fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.07.092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Essien UR, Holmes DN, Jackson LR, et al. Association of Race/Ethnicity With Oral Anticoagulant Use in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(12):1174. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse. https://www2.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories. Published 2019. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- 11.Lip GYH, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJGM. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: The Euro Heart Survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, De Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, Lip GYH. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: The euro heart survey. Chest. 2010. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazurek M, Huisman M V., Lip GYH. Registries in Atrial Fibrillation: From Trials to Real-Life Clinical Practice. Am J Med. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piccini JP, Xu H, Cox M, et al. Adherence to Guideline-Directed Stroke Prevention Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation is Achievable: First Results from Get With The Guidelines-Atrial Fibrillation (GWTG-AFIB). Circulation. 2019. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson LR, Peterson ED, Okeagu E, Thomas K. Review of race/ethnicity in non vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants clinical trials. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;39(2):222–227. doi: 10.1007/s11239-014-1145-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson LE, Maddox TM, Lei L, et al. Sex differences in the use of oral anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation: A report from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR®) PINNACLE registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shulman E, Chudow JJ, Essien UR, et al. Relative contribution of modifiable risk factors for incident atrial fibrillation in Hispanics, African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites. Int J Cardiol. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong SL, Marshall LZ, Lawson KA. Direct oral anticoagulant prescription trends, switching patterns, and adherence in Texas medicaid. Am J Manag Care. 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.