Abstract

BACKGROUND

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is a risk factor for gastric cancer (GC), especially in East Asian populations. Most East Asian populations infected with H. pylori are at higher risk for GC than H. pylori-positive European and United States populations. H. pylori eradication therapy reduces gastric cancer risk in patients after endoscopic and operative resection for GC, as well as in non-GC patients with atrophic gastritis.

AIM

To clarify the chemopreventive effects of H. pylori eradication therapy in an East Asian population with a high incidence of GC.

METHODS

PubMed and the Cochrane library were searched for randomized control trials (RCTs) and cohort studies published in English up to March 2019. Subgroup analyses were conducted with regard to study designs (i.e., RCTs or cohort studies), country where the study was conducted (i.e., Japan, China, and South Korea), and observation periods (i.e., ≤ 5 years and > 5 years). The heterogeneity and publication bias were also measured.

RESULTS

For non-GC patients with atrophic gastritis and patients after resection for GC, 4 and 4 RCTs and 12 and 18 cohort studies were included, respectively. In RCTs, the median incidence of GC for the untreated control groups and the treatment groups was 272.7 (180.4–322.4) and 162.3 (72.5–588.2) per 100000 person-years in non-GC cases with atrophic gastritis and 1790.7 (406.5–2941.2) and 1126.2 (678.7–1223.1) per 100000 person-years in cases of after resection for GC. Compared with non-treated H. pylori-positive controls, the eradication groups had a significantly reduced risk of GC, with a relative risk of 0.67 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.47–0.96] for non-GC patients with atrophic gastritis and 0.51 (0.36–0.73) for patients after resection for GC in the RCTs, and 0.39 (0.30–0.51) for patients with gastritis and 0.54 (0.44–0.67) for patients after resection in cohort studies.

CONCLUSION

In the East Asian population with a high risk of GC, H. pylori eradication effectively reduced the risk of GC, irrespective of past history of previous cancer.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Eradication therapy, Gastric cancer, Metachronous cancer, East Asia, Prevention

Core tip: No meta-analysis is available in the literature about the chemopreventive effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy on the incidence of gastric cancer (GC) focused on East Asian populations living in geographical areas with high incidences of GC. We conducted a meta-analysis to reevaluate the prevention of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy on the incidence of GC, irrespective of history of endoscopic or surgical treatment for GC.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the major cancers in the world, especially in East Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea, and China. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-associated GC is caused by multifactorial and multistep process. The International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization categorized H. pylori as a group I carcinogenic factor of GC in 1994[1,2]. Many clinical trials have shown that H. pylori infection is associated with an elevated risk of GC development not only in patients with atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia alone, but also in patients already treated by resection of GC (Table 1). Due to the small sample size in each report, however, it remains unclear whether the risk of GC related to H. pylori is similar among patients with atrophy and intestinal metaplasia alone compared with post-resection patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies

| Ref. | Country | Primary or metachron-ous cancer | Design | Disease at basement | Follow-up periods (yr) | Patients number | Age (yr) | Sex (male/ female) | Regimen of eradica-tion therapy | Eradica-tion rate (%) |

| Fukase et al[31], 2006 | Japan | Metachron-ous | RCT | Gastric cancer | 3 | 544 | 68 (62-73) | 386/119 | LPZ(30)/AMPC(750)/CAM(200), BID, 7D | 75.0 |

| Choi et al[32], 2018 | South Korea | Metachron-ous | RCT | Gastric cancer | 5.9 | 396 | 59 | 298/104 | RPZ(10)/AMPC(1000)/CAM(500), BID 7D | 80.4 |

| Choi et al[33,69] | South Korea | Metachron-ous | RCT | Gastric cancer | 6 | 898 | 60.4 | 594/283 | OPZ(20)/AMPC(1000)/CAM(500), BID 7D | 82.6 |

| Uemura et al[70], 1997 | Japan | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 3 | 132 | 69 (44-85) | 97/35 | 1st: OPZ(20)/CAM(400) 14D, 2nd: OPZ(20)/AMPC(1500)/MNZ(500), BID 14D | 46.2 |

| Nakagawa et al[71], 2006 | Japan | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 2 | 2825 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Shiotani et al[72], 2008 | Japan | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 2.75 | 100 | 69 | 67/13 | PPI/AMPC(750)/CAM(200), BID 7D | 81.3 |

| Han et al[73], 2011 | South Korea | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 2.7 | 176 | 61.8 (43-83) | 112/64 | NA | NA |

| Kim et al[74], 2011 | South Korea | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 5.1 | 55 | 60.7 (43-81) | 36/19 | NA | 50.9 |

| Maehata et al[75], 2012 | Japan | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 3 | 268 | 69 (49-90) | 194/74 | PPI/AMPC(750)/CAM(200), BID 7D | 78.2 |

| Seo et al[76], 2013 | South Korea | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 2.27 | 74 | 62 | 55/19 | PPI/AMPC(1000)/CAM(500), BID 7-14D | 82.4 |

| Kato et al[77], 2013 | Japan | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 2.23 | 368 | 70.5 | 953/305 | NA | NA |

| Bae et al[78], 2014 | South Korea | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 5 | 1007 | 63 (28-88) | 785/222 | PPI/AMPC(750)/CAM(200), BID 7-14D | NA |

| Kim et al[79], 2014 | South Korea | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 4.3 | 374 | 64 (35-87) | 278/96 | PPI/AMPC(1000)/CAM(500), BID 7D | 72.1 |

| Kwon et al[80], 2014 | South Korea | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 3.4 | 283 | 59 | 190/93 | PPI/AMPC(750)/CAM(200), BID 7D | 68.9 |

| Jung et al[27], 2015 | South Korea | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 3.36 | 1041 | 62.7 | 773/268 | LPZ(30)/AMPC(1000)/CAM(500), BID 7-14D | NA |

| Lim et al[28], 2015 | South Korea | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 3.1 | 933 | 63.0 ± 9.51 | 512/250 | NA | NA |

| Kim et al[81], 2016 | Korea | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 2.5 | 257 | 67 | 189/68 | PPI/AMPC(1000)/CAM(500), BID 7D | 86.3 |

| Ami et al[82], 2017 | Japan | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 4.47 | 438 | 69.4 ± 8.7 | 421/118 | LPZ(30) or RPZ(10)/AMPC(750)/CAM(200), BID 7-14D | NA |

| Kwon et al[29], 2017 | South Korea | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 3.725 | 590 | 63 | 398/192 | RPZ(20)/AMPC(1000)/CAM(500), BID 7D | 81.8 |

| Chung et al[30], 2017 | South Korea | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 5.125 | 185 | 67.4 (45-87) | 141/44 | PPI/AMPC/CAM, BID 7D | NA |

| Han et al[83], 2018 | South Korea | Metachron-ous | Cohort | Gastric cancer | 5 | 565 | 61 | 440/125 | NA | NA |

| Cho et al[17], 2013 | South Korea | Metachron-ous | RCT | Gastric cancer | 3 | 169 | 56 | 117/52 | RPZ(10)/AMPC(1000)/CAM(500), BID 7D | 77 |

| Wong et al[18], 2004 | China | Primary | RCT | Gastritis alone | 7.5 | 1630 | 42.2 (35-65) | 880/750 | OPZ(20)/AMPC(750)/MNZ(400), BID 14D | 82.5 |

| Ma et al[23], You et al[84] and Li et al[85] | China | Primary | RCT | Non-gastric cancer | 14.3 | 2258 | 47.1 | 1808/1603 | OPZ(20)/AMPC(1000), BID 7D | 66.2 |

| Wong et al[19], 2012 | China | Primary | RCT | With/with-out metaplasia | 2 | 1024 | 53.0 (35-64) | 473/551 | PPI/AMCP(1000)/CAM(500), BID 7D | 71.3 |

| Zhou et al[24], 2014, Leung et al[86], 2004 | China | Primary | RCT | Non-gastric cancer | 10 | 554 | 53.35 ± 8.49 | 268/284 | OPZ(20)/AMPC(1000)/CAM(500), BID 7D | 88.9 |

| Saito et al[22], 2000 | Japan | Primary | Cohort | Gastric adenoma | 2 | 64 | 79.2 (68-92) | 35/29 | OPZ(20)/AMCP(1000)/CAM(400), BID 7D | 75 |

| Uemura et al[52], 2001 | Japan | Primary | Cohort | With/with-out PU | 7.7 | 1526 | 52.4 | 869/657 | NA | NA |

| Kato et al[87], 2006 | Japan | Primary | Cohort | With/with-out PU | 5.9-7.7 | 3021 | 54 | 1868/1153 | LPZ(30)/AMPC(750)/CAM(200), BID 7-14D | NA |

| Takenaka et al[88], 2007 | Japan | Primary | Cohort | With/with-out PU | 3.17 | 1807 | 53.6 ± 12.4 | 1289/518 | Dual therapy or PPI/AMPC(750)/CAM(200 or 400), BID 7D | 82.9 |

| Ogura et al[89], 2008 | Japan | Primary | Cohort | With/with-out PU | 3.2 | 708 | 62 | 400/308 | LPZ(30)/AMPC(750/1000)/CAM(400) or MNZ(250), BID 7D | 74 |

| Kim et al[90], 2008 | South Korea | Primary | Cohort | With/with-out PU | 9.4 | 1790 | 46.7 | 1483/297 | Tripotassi-um dicitrate bismuthate (300, QID)/MNZ(500, TID)/TC(500, QID), 5D or OPZ(20)/CAM(500)/AMPC(1000)BID 7D | NA |

| Mabe et al[53], 2009 | Japan | Primary | Cohort | With/with-out PU | 5.6 | 4133 | 52.9 (13-91) | 2964/1169 | LPZ(30) or OPZ(20)/AMPC(750)/CAM(200 or 400), BID 7D | 64.8 |

| Yanaoka et al[25], 2009 | Japan | Primary | Cohort | Non-gastric cancer | 9.3 | 4129 | 49.8 | 5560/107 | OPZ(20)/AMPC(750 or 500), BID 14D, OPZ(20)/AMPC(750)/CAM(200), BID 7D | 87.2 |

| Watanabe et al[26], 2012 | Japan | Primary | Cohort | Non-gastric cancer | 5.4 | 823 | NA | NA | OPZ(20, BID)/AMPC(750 or 500, BID) 14D or OPZ(20)/AMPC(750)/CAM(200), BID 7D | 82.0 |

| Lee et al[20], 2013 | China | Primary | Cohort | With/with-out PU or dysplaisa | 5 | 8242 | 49.2 ± 12.8 | 1888/2233 | PPI/AMCP(1000)/CAM(500), BID 7D | 78.7 |

| Shichijo et al[21], 2015 | Japan | Primary | Cohort | Intestinal metaplasia | 6.7 ± 4.7 | 659 | 60.1 ± 11.0 | 374/355 | LPZ(30)/AMPC(750 or 1000)/CAM(200) or MNZ(250), BID 7D | NA |

| Take et al[91-94] | Japan | Primary | Cohort | Peptic ulcer | 9.9 | 1222 | 49.9 ± 8.3 | 1087/135 | Dual or Triple therapy | NA |

Non-gastric cancer: patients had no history of gastric cancer, but were unknown to have peptic ulcer and dysplasia. AMPC: Amoxicillin; BID: Twice-daily dosing; CAM: Clarithromycin; D: Day; LPZ: Lansoprazole; MNZ: Metronidazole; NA: Not available; OPZ: Omeprazole; PPI: Proton pump inhibitor; PU: Peptic ulcer; QID: Four-times daily dosing; RCT: Randomized control trial; RPZ: Rabeprazole; TID: Three-times daily dosing; TC: Tetracycline.

With or without H. pylori infection, severe gastric mucosal atrophy and intestinal metaplasia are well-known risk factors for peptic ulcers as well as GC[3,4]. Several pathological reporting systems, including the Sydney system, its Houston-updated version, and the operative link on gastritis assessment system, as well as endoscopic reporting systems, such as the Kyoto classification of gastritis, are used to select patients at high risk for GC based on severity of pathological or endoscopic gastric mucosal atrophy and intestinal metaplasia[4-7]. In addition, the severity of gastric mucosal inflammation, atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia has been shown to correlate with H. pylori virulence factors (i.e., cagA, vacA and oipA)[8-11]. Because > 90% of H. pylori isolated from East Asian populations carry the cagA, which is associated with increased proliferation and pro-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic gene expression, and the vacA s1m1 type, which is associated with enhanced production of toxin with higher vacuolating activity[12,13], most East Asian populations infected with H. pylori are at higher risk for GC than H. pylori-positive European and United States populations. Thus, it is important to evaluate the association of H. pylori infection with GC risk in East Asian populations in order to formulate strategies to reduce the risk of GC.

Many clinical trials have shown that eradication of H. pylori infection reduces the risk of GC development (Table 1). Following H. pylori eradication therapy, a gradual decrease in severity of gastric atrophy in the gastric body and antrum and intestinal metaplasia in the body has been shown[14]. In 2012, the Japanese health insurance system began to cover H. pylori eradication treatment in patients with endoscopically-confirmed H. pylori-associated gastritis. International guidelines strongly recommend eradication of H. pylori in patients to prevent development of GC[15,16]. However, it remains unclear whether eradication therapy exerts the same preventive effect on GC among different groups, e.g., those of different nationalities, those with a history of gastritis, those with a prior history of GC resection, etc., with different risk levels for GC development.

In general, the risk of GC development differs between Western population and East Asian population, due to different life style, different genetics, and different H. pylori strain. Although it is important to evaluate the risk of GC separately for Western and East Asian population, previous meta-analysis did not evaluate this point and meta-analyzed all of studies, irrespective with nationalities. Thus, it is required to evaluate the association of H. pylori infection with GC risk in East Asian populations in order to formulate strategies to reduce the risk of GC. We conducted a meta-analysis to reevaluate the preventive effects of H. pylori eradication therapy on the incidence of GC, irrespective of history of endoscopic or surgical treatment for GC, especially in East Asian populations living in geographical areas with high incidences of GC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

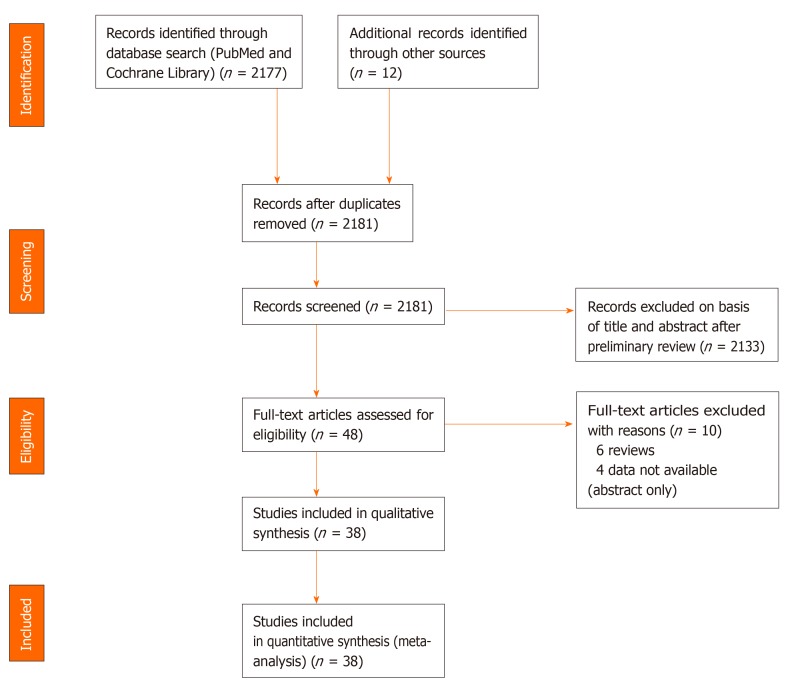

For a meta-analysis to investigate preventive effects of eradication therapy on GC development, we conducted a search of the medical literature using data of randomized control trials (RCTs) and cohort studies. Two researchers (MS and MM) independently searched both the PubMed and Cochrane Library databases using the terms “H. pylori,” “GC,” and “eradication therapy,” and reviewed titles and abstracts for all potential studies (Figure 1). The inclusion criteria were: (1) RCTs or cohort studies published in English up to March 2019; and (2) Studies comparing individuals receiving H. pylori eradication with those not receiving eradication treatment with respect to the incidence of primary GC in East Asian non-GC patients with gastritis or metachronous cancer in patients after resection of GC, irrespective with primary outcome or secondly outcome. All GC, including gastric dysplasia, was endosco-pically and pathologically diagnosed. Study included patients with GC or gastric dysplasia as gastric neoplasm was included as GC group in this meta-analysis. In non-GC patients with atrophic gastritis, the basement diseases before H. pylori eradication therapy were included atrophic gastric alone, peptic ulcer, gastric dysplasia and gastric adenoma. The full texts of potential studies were then screened to select studies meeting the inclusion criteria, and duplicated studies and multiple reports of the same study were excluded. When multiple articles were found, we used data from the latest publication date. Metachronous cancer was defined as a newly developed cancer at another site in the stomach > 1 year after resection for cancer. The exclusion criteria were (1) Non-East Asian patients; (2) Single-arm studies without a non-eradicated control group; and (3) Studies with an observation period < 1 year after eradication therapy.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Authors, publication year, country where the study was conducted, study design, numbers of treatment groups and control groups, number of patients developing GC, observation periods, patient conditions at baseline (sex and age), and pathological differentiation of GC were extracted from each study.

Statistical analysis

First, we divided studies into two kinds of clinical design: Non-GC patients with atrophic gastritis (at risk for primary GC) and patients after endoscopic and operative resection of early-stage GC (at risk for metachronous GC), because of their significantly different risk of cancer development. Subgroup analyses were conducted with regard to study designs (i.e., RCTs or cohort studies), country where the study was conducted (i.e., Japan, China, and South Korea), and observation periods (i.e., ≤ 5 years and > 5 years). The potential study bias in each study was evaluated by funnel plots. Heterogeneity was evaluated by I2 value and Cochran’s Q. The I2 value was used to assess the heterogeneity of the studies as follows: 0%–39%, low heterogeneity; 40%–74%, moderate heterogeneity; and 75%–100%, high heterogeneity. The relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of each study were reported as the measure of effect size. All meta-analyses were conducted using open-source statistical software (Review Manager Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, the Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). All P values were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Calculations were performed using commercial software (SPSS version 20, IBM Inc; Armonk NY, United States).

RESULTS

Literature search and data extraction

A total of 38 studies which investigated the chemopreventive effects of H. pylori eradication on GC development among East Asian populations were included in the meta-analysis (Figure 1), consisting of 16 studies (4 RCTs and 12 cohort studies) in naïve non-GC patients with gastritis and 22 studies (4 RCTs and 18 cohort studies) in patients after resection for GC. Of 22 studies investigating the risks of metachronous cancers, a study from Cho et al[17] was included for post-surgical resection cases. In naïve non-GC patients with atrophic gastritis, the basement diseases before H. pylori eradication therapy were included atrophic gastric alone[18], peptic ulcer, gastric dysplasia[19-21] and gastric adenoma[22] or detail data not shown (but without history of GC)[23-26].

Finally, a total of 32775 non-GC cases with gastritis (5464 cases from RCTs and 27311 cases from cohort studies) and 9605 cases after resection for cancer (2007 cases for RCTs and 7598 cases from cohort studies) were included in this analysis (Table 1).

Four studies evaluated patients included GC or gastric dysplasia as gastric neoplasm[27-30]. The mean or median follow-up period ranged from 2.0–14.3 years, and the mean or median age of patients ranged from 46.7–79.2 years (Table 1). The ratio of males was from 46.2% to 98.1%. In most studies, H. pylori eradication therapy was performed using a regimen including proton pump inhibition (PPI) [i.e., omeprazole (20 mg, bid), lansoprazole (30 mg, bid), rabeprazole (10 or 20 mg, bid) or esomeprazole (20 mg, bid)] and two kinds of antimicrobial agents [i.e., clarithromycin (200, 400, or 500 mg, bid), amoxicillin (750 or 1000 mg, bid, or 500 mg, tid), and metronidazole (250 or 500 mg, bid)] (Table 1). In the RCTs, eradication rates were 66.2%–88.9% in studies for non-GC cases with gastritis and 75.0%–82.6% in cases after gastric resection (Table 1).

The median incidence of GC for the untreated control groups in non-GC cases of gastritis was 322.4 (68.7–1379.5) per 100000 person-years. Those in RCTs and cohort studies were 272.7 (180.4–322.4) and 467.2 (68.7–1379.5) per 100000 person-years, respectively (Table 2). In the treatment groups, median incidences of cancer in all studies, RCTs and cohort studies were 114.2 (0–588.2), 162.3 (72.5–588.2) and 113.7 (0–464.1) per 100000 person-years, respectively.

Table 2.

Gastric cancer development and histological characteristics

| Ref. | Design | Follow-up periods (yr) |

Eradicated group |

Non-eradicated control group |

Eradicated group |

Non-eradicated control group |

||||

| Cancer/ Total | Cancer incidence, /100000 PY | Cancer/ Total | Cancer incidence, /100000 PY | Intestinal type | Diffuse type | Intestinal type | Diffuse type | |||

| Patients after resection for gastric cancer | ||||||||||

| Fukase et al[31], 2006 | RCT | 3 | 9/272 | 1102.9 | 24/272 | 2941.2 | 9 | 0 | 23 | 1 |

| Choi et al[32], 2018 | RCT | 5.9 | 14/194 | 1223.1 | 27/202 | 2265.5 | 14 | 0 | 25 | 1 |

| Choi et al[33,69] | RCT | 6 | 18/442 | 678.7 | 36/456 | 1315.8 | 13 | 5 | 26 | 8 |

| Uemura et al[70], 1997 | Cohort | 3 | 0/65 | 0 | 6/67 | 2985.1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Nakagawa et al[71], 2006 | Cohort | 2 | 8/356 | 864.3 | 129/2469 | 2902.7 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Shiotani et al[72], 2008 | Cohort | 2.75 | 9/80 | 4090.9 | 1/11 | 3305.8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Han et al[73], 2011 | Cohort | 2.7 | 4/94 | 1576 | 2/22 | 3367 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kim et al[74], 2011 | Cohort | 5.1 | 0/28 | 0 | 5/27 | 3631.1 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Maehata et al[75], 2012 | Cohort | 3 | 15/177 | 2824.9 | 13/91 | 4761.9 | 14 | 1 | 13 | 0 |

| Seo et al[76], 2013 | Cohort | 2.27 | 6/61 | 4333.1 | 3/13 | 10166 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kato et al[77], 2013 | Cohort | 2.23 | 24/263 | 4092.1 | 6/105 | 2562.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Bae et al[78], 2014 | Cohort | 5 | 34/485 | 1402.1 | 24/182 | 2637.4 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kim et al[79], 2014 | Cohort | 4.3 | 2/49 | 770.1 | 16/107 | 3250.7 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kwon et al[80], 2014 | Cohort | 3.4 | 18/214 | 2473.9 | 13/69 | 5541.3 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 4 |

| Jung et al[27], 2015 | Cohort | 3.36 | 21/506 | 1235.2 | 10/169 | 1761.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Lim et al[28], 2015 | Cohort | 3.1 | 7/236 | 956.8 | 6/276 | 701.3 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kim et al[81], 2016 | Cohort | 2.5 | 3/120 | 902.5 | 1/42 | 872.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ami et al[82], 2017 | Cohort | 4.47 | 25/212 | 2638.1 | 1/14 | 1598 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kwon et al[29], 2017 | Cohort | 3.725 | 33/368 | 2255.9 | 8/27 | 7454 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| Chung et al[30], 2017 | Cohort | 5.125 | 17/167 | 1986.3 | 7/18 | 7588.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Han et al[83], 2018 | Cohort | 5 | 12/212 | 1132.1 | 18/196 | 1836.7 | 11 | 1 | 18 | 0 |

| Cho et al[17], 2013 | RCT | 3 | 3/87 | 1149.4 | 1/82 | 406.5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Patients with gastritis | ||||||||||

| Wong et al[18], 2004 | RCT | 7.5 | 7/817 | 114.2 | 11/813 | 180.4 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ma et al[23], You et al[84] and Li et al[85] | RCT | 14.3 | 34/1130 | 210.4 | 52/1128 | 322.4 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wong et al[19], 2012 | RCT | 2 | 6/510 | 588.2 | 3/514 | 291.8 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Zhou et al[24], 2014, Leung et al[86], 2004 | RCT | 10 | 2/276 | 72.5 | 7/276 | 253.6 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Saito et al[22], 2000 | Cohort | 2 | 0/32 | 0 | 4/32 | 6250 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Uemura et al[52], 2001 | Cohort | 7.7 | 0/253 | 0 | 36/993 | 424.4 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 13 |

| Kato et al[87], 2006 | Cohort | 5.9-7.7 | 23/1788 | 218 | 44/1233 | 467.2 | 19 | 4 | 32 | 12 |

| Takenaka et al[88], 2007 | Cohort | 3.17 | 6/1519 | 121.5 | 5/288 | 598.7 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Ogura et al[89], 2008 | Cohort | 3.2 | 6//404 | 464.1 | 13/304 | 1379.5 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| Kim et al[90], 2008 | Cohort | 9.4 | 1/476 | 22.3 | 4/977 | 43.6 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Mabe et al[53], 2009 | Cohort | 5.6 | 47/3781 | 222 | 9/352 | 491.7 | 35 | 10 | 5 | 4 |

| Yanaoka et al[25], 2009 | Cohort | 9.3 | 5/473 | 113.7 | 55/3656 | 161.8 | 4 | 1 | 36 | 19 |

| Watanabe et al[26], 2012 | Cohort | 5.4 | 0/327 | 0 | 7/496 | 261.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Lee et al[20], 2013 | Cohort | 5 | 15/4121 | 72.8 | 16/4121 | 77.7 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Shichijo et al[21], 2015 | Cohort | 6.7 ± 4.7 | 4/260 | 229.6 | 13/203 | 955.8 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Take et al[91-94] | Cohort | 9.9 | 24/1133 | 214 | 6/89 | 681 | 14 | 10 | 5 | 1 |

NA: Not available; RCT: Randomized control trial; PY: Person-year.

The median incidence of metachronous GC for the H. pylori-positive non-treated control groups after endoscopic and operative gastric resection was 2922.0 (406.5–10,166.0) per 100000 person-years. Those in RCTs and cohort studies were 1790.7 (406.5–2941.2) and 3117.9 (701.3–10166.0) per 100000 person-years, respectively (Table 2).

In the treatment groups, median incidence of metachronous GC in all, RCTs and cohort studies were 1229.2 (0–4333.1), 1126.2 (678.7–1223.1) and 1489.1 (0–4333.1) per 100000 person-years (Table 2).

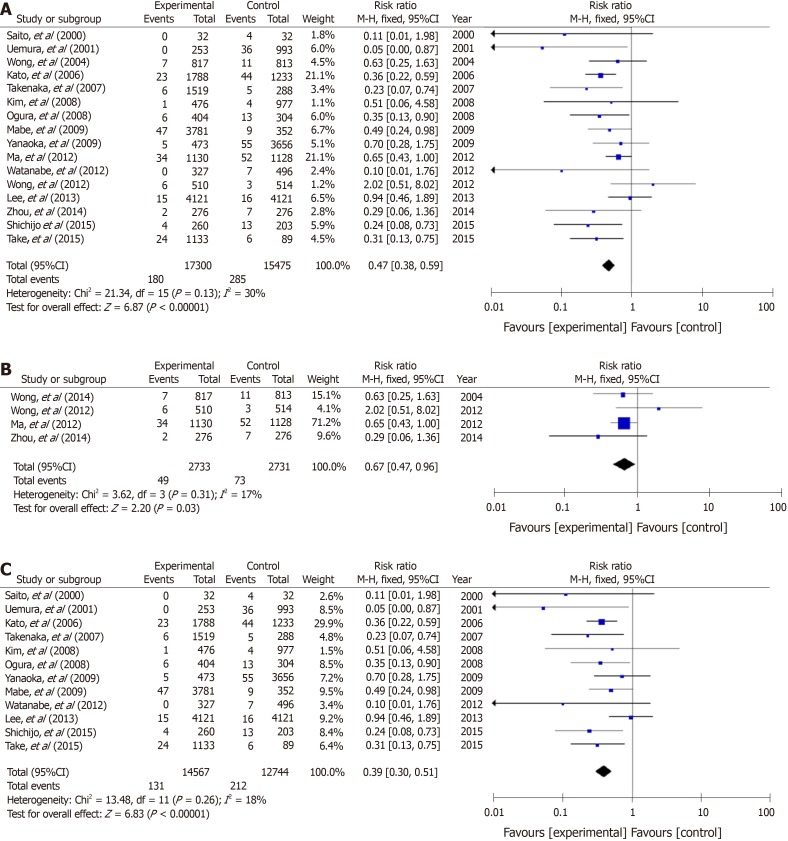

Meta-analysis of GC risk in treated groups and untreated control group

In non-GC patients with gastritis, when combined with 4 RCTs[18,19,23,24] and 12 cohort studies, 180 (1.0%) patients developed GC among 17300 individuals who underwent eradication, and 285 (1.8%) patients did so among 15475 individuals in the untreated control group (Figure 2A). The RR for GC in the treatment groups compared with H. pylori-positive controls was 0.47 (95%CI: 0.38–0.59) (Figure 2A). No heterogeneity was found among the studies.

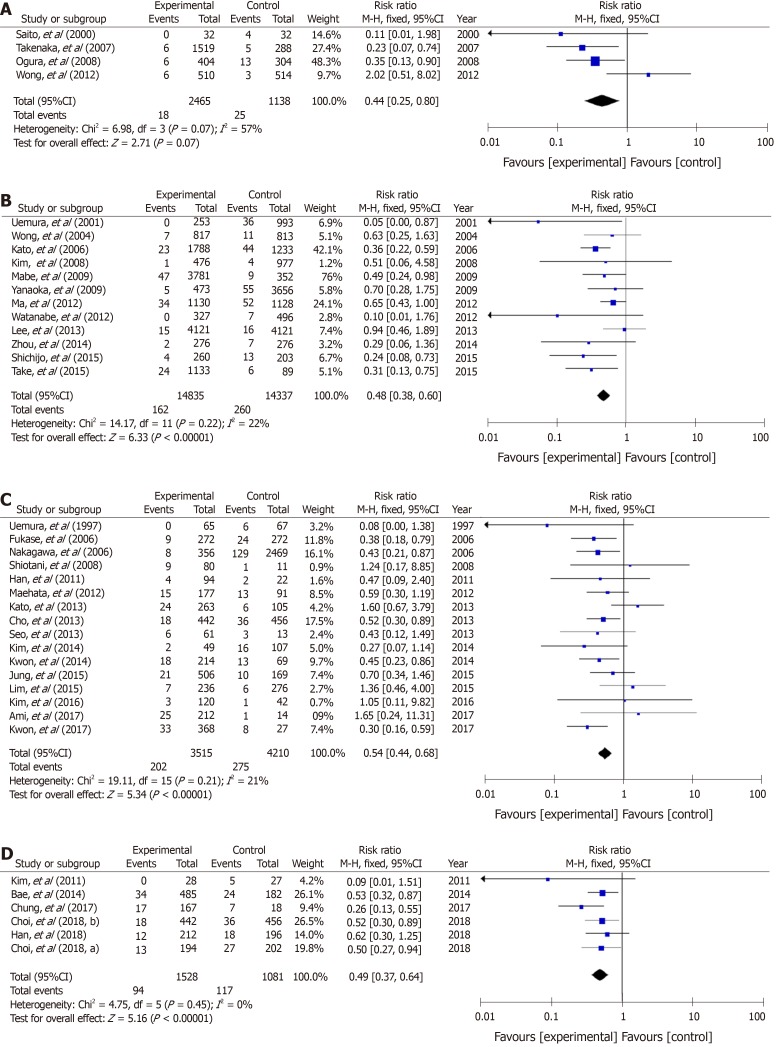

Figure 2.

A forest plots for the incidence of gastric cancer between Helicobacter pylori-eradication group and non-eradication group in 16 studies combined with randomized control studies and cohort studies (A), 4 randomized control studies (B) and 12 cohort studies (C) in non-gastric cancer patients with atrophic gastritis. There was no heterogeneity in the total analysis (I2 = 30%, P = 0.13), randomized control studies (I2 = 17%, P = 0.31) and cohort studies (I2 = 18%, P = 0.26). A: Randomized control studies + Cohort studies; B: Randomized control studies; C: Cohort studies.

In 4 RCTs[18,19,23,24], GC developed in 49 (1.8%) patients among 2733 H. pylori-negative treated cases, and in 73 (2.7%) patients among 2731 H. pylori-positive controls (Figure 2B). The mean RR comparing the H. pylori-negative eradicated group with the H. pylori-positive control group was 0.67 (95%CI: 0.47–0.96) (Figure 2B). No heterogeneity was found among the studies. In addition, in the cohort studies, the mean RR in the H. pylori-negative eradicated group was 0.39 (95%CI: 0.30–0.51) compared with the H. pylori-positive controls (Figure 2C).

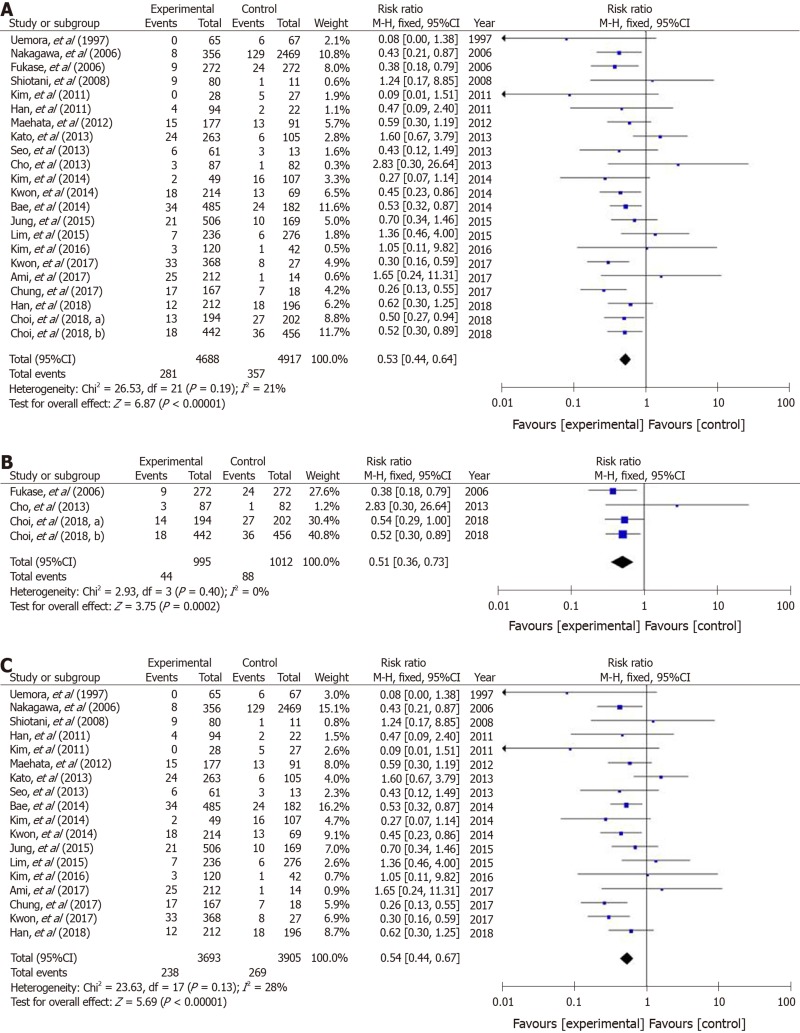

In studies of a combination of 4 RCTs and 18 cohort studies of patients after endoscopic and operative resection, metachronous cancer occurred in 281 (6.0%) patients among 4688 treated individuals, and in 357 (7.3%) cases among 4917 cases in the H. pylori-positive control groups. The RR for metachronous cancer comparing H. pylori-negative treated groups with H. pylori-positive controls was 0.53 (95%CI: 0.44–0.64) (Figure 3A). No heterogeneity was found among the studies.

Figure 3.

A forest plots for the incidence of metachronous gastric cancer between Helicobacter pylori-eradication group and non-eradication group in 22 studies combined with randomized control studies and cohort studies (A), 4 randomized control studies (B) and 18 cohort studies (C) in patients after endoscopic and operative resection. No heterogeneity in the total analysis (I2 = 21%, P = 0.19), Randomized control studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.40) and cohort studies (I2 = 28%, P = 0.13) was shown. A: Randomized control studies + Cohort studies; B: Randomized control studies; C: Cohort studies.

In the four RCTs[17,31-33], metachronous cancer occurred in 44 (4.4%) cases from 995 H. pylori-negative individuals, and in 88 (8.7%) cases among 1012 H. pylori-positive controls (Figure 3B). The RRs of the H. pylori-negative treated groups in RCTs and cohort studies were 0.51 (95%CI: 0.36–0.73) and 0.54 (0.44–0.67), respectively (Figure 3B and C).

Quality assessment

The funnel plot of all included studies did not suggest asymmetry in non-GC patients with atrophic gastritis and patients after resection of GC Supplementary Figure (1A and B), and statistical analysis with Egger’s test also confirmed that there was no publication bias according to different set of primary outcomes.

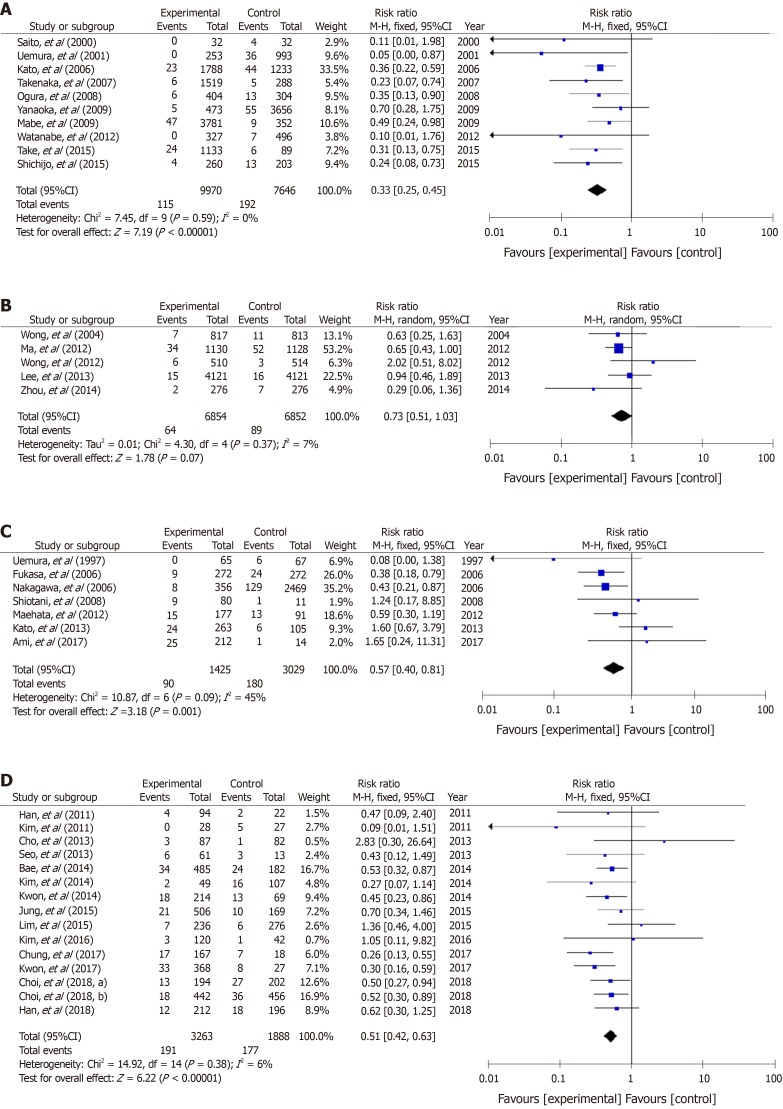

Subgroup analysis by different countries and observation periods

A total of 16 studies of cases of gastritis-10 from Japan, 5 from China, and 1 from South Korea—were analyzed (Figure 4A and B). The RR of the Japanese studies was 0.33 (95%CI: 0.25–0.45), which was lower than that from China (0.73; 0.51–1.03) and South Korea (0.51; 0.06–4.58) (Figs 4A and B). Seven Japanese and 15 Korean studies of post-gastric resection cases were conducted (Figure 4C and D). The RRs for metachronous cancer were similar between Japan (RR 0.57; 95%CI: 0.40–0.81) and South Korea (0.51; 0.42–0.63) (Figure 4C and D). When observation periods were subgrouped into ≤ 5 years and > 5 years, the RRs were similar between the two subgroups in studies of non-GC cases of gastritis, and in studies of cases after resection of GC (Figure 5A-D).

Figure 4.

Forest plots of the incidence of gastric cancer between Helicobacter pylori-negative and positive groups with atrophic gastritis in studies published in different countries; 10 studies from Japan (A) and 5 from China (B). Forest plots of the incidence of metachronous gastric cancer between Helicobacter pylori-negative and positive groups presenting with gastric cancer in 7 studies from Japan (C) and 15 from South Korea (D). A: Non-gastric cancer patients with atrophic gastritis: Japan; B: Non-gastric cancer patients with atrophic gastritis: China; C: Metachronous gastric cancer: Japan; D: Metachronous gastric cancer: South Korea.

Figure 5.

Forest plots of the incidence of gastric cancer between Helicobacter pylori-negative and -positive groups with atrophic gastritis in studies of different observation period length, < 5 years (A) and > 5 years (B). Forest plots of the incidence of metachronous gastric cancer in cases treated for gastric cancer in studies of different observation period length, < 5 years (C) and > 5 years (D). A: Non-gastric cancer with atrophic gastritis: within 5 years of resection; B: Non-gastric cancer with atrophic gastritis: more than 5 years after resection; C: Metachronous cancer: within 5 years of resection; D: Metachronous cancer: more than 5 years after resection.

Characteristics of GC after eradication therapy

Of non-GC patients with gastritis developing later cancer, 73.3% (85/116) of H. pylori-negative eradicated cases and 67.7% (126/186) of H. pylori-positive untreatedcontrols were observed be of the intestinal type (P = 0.31) (Table 2). Of patients developing metachronous cancers after endoscopic and operative resection of cancer, 84.0% (89/106) H. pylori-negative eradicated and 88.4% (122/138) H. pylori-positive non-treatment controls were observed to be of the intestinal type (P = 0.31) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this meta-analysis, we evaluated whether H. pylori eradication therapy effectively reduced the risk of GC development in both non-GC patients with gastritis and patients after endoscopic and surgical resection for GC, especially in East Asian populations with high incidence rates of GC. This meta-analysis of 38 studies (16 studies in non-GC patients with gastritis and 22 in patients after gastric resection) showed that eradication therapy had a significant protective effect against development of GC with mean RRs of 0.47 (95%CI: 0.38–0.75) and 0.53 (95%CI: 0.44–0.64), irrespective of study design (RCTs or cohort studies), past history of GC, countries of origin, and observation periods after eradication therapy. This efficacy was similar to the previous meta-analysis performed by Yoon et al[34] (OR: 0.42; 95%CI: 0.32–0.56), Xiao et al[35] (RR: 0.50; 95%CI: 0.41–0.61), and Sugano[36] [OR: 0.46; 95%CI: 0.39–0.55]. Our observations suggest that H. pylori eradication therapy should be performed in all patients with H. pylori infection to prevent development of GC in East Asian populations.

Characteristics of GC risk in East Asian populations

Considered globally, East Asian countries, especially South Korea, have a high age-standardized incidence rate for GC. The age-standardized incidence rate per 100000 persons in 2018 was 39.6 in both sexes (57.8 in men and 23.5 in women) in South Korea, followed by 27.5 (40.7 and 16.0) in Japan and 20.7 (29.5 and 12.3) in China, vs a world rate in 2012 of 12.1 (17.4 and 7.5, respectively)https://(www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer/cancer-trends/stomach-cancer-statistics). As observed in global trends, however, in accordance with the increased chance of receiving H. pylori eradication therapy[37] resulting in a decrease in infection rates across the population[38] and improvement of sanitary conditions, incidence rates of GC are gradually declining, particularly H. pylori-associated non-cardia GC[37]. In Japan, although approximately 50000 GC deaths occurred annually over 40 years, deaths significantly decreased from 48427 in 2013 to 45509 in 2016 following expansion of insurance coverage for H. pylori eradication therapy[37]. In addition, national GC screening programs using upper endoscopy in South Korea and Japan may have contributed to the decrease of GC mortality by decreasing the risk of diagnosis at an advanced stage and by H. pylori eradication therapy after endoscopic diagnosis[39]. Currently, approximately half of all GCs in Japanese are detected at an early stage, confined to the mucosa or submucosa[40]. Establishment of an effective screening system for GC detection and the stratification of risk for GC development are considered to be important for reducing GC development and mortality.

Chemoprevention for metachronous GC

Endoscopic resection, including endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection for early-stage GC, are widely accepted as curative[41]. With the development of treatment tools and endoscopy, endoscopic submucosal dissection is used as first-line treatment for early-stage GC in Japan and South Korea, because it enables en bloc resection of GC[42-44]. However, the risk of metachronous cancer after endoscopic resection is expected to be higher than the risk in non-GC patients with gastritis, and a drawback of endoscopic and operative resection is the residual risk of metachronous cancer arising from severe atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia in the gastric remnant. In general, metachronous GCs are characterized as small, differentiated intramucosal cancers < 20 mm in size. The incidence rate of metachronous cancer within 3–5 years after endoscopic resection has been reported to be about 2.7%–15.6%[45]. The median incidence of metachronous cancer decreased to 1229.2 (0–4333.1) per 100000 person-years after eradication therapy from 2922.0 (406.5–10,166.0) in H. pylori-positive individuals in this meta-analysis. In a multicenter RCT by the Japan GAST Study Group in 2008, the cumulative incidence of metachronous cancer was 6.5% during 3-years follow-up. H. pylori eradication therapy decreased the incidence of metachronous cancer by approximately two-thirds in patients after endoscopic resection for early-stage GC (3.5% vs 9.6%, P = 0.003)[31]. Also in an RCT from South Korea, during a median follow-up of 5.9 years, metachronous cancer developed in 7.2% of patients who underwent successful eradication therapy and 13.4% of patients receiving placebo (HR: 0.50; 95%CI: 0.26–0.94), correlating with improvement in gastric corpus atrophy[32]. In this meta-analysis, only 36.4% of all studies (all 3 RCTs and five studies of 18 cohort studies in patients after endoscopic resection) showed significant reduction of metachronous cancer risk. This observation may have been caused by the small sample size in each report and it remains unclear whether the risk of GC related to H. pylori decrease after eradication therapy. The RRs with eradication therapy in RCTs and cohort studies were 0.51 (95%CI: 0.36–0.73) and 0.54 (0.44–0.67), respectively. Therefore, we recommend that all East Asian patients who remain H. pylori-positive after endoscopic resection for GC receive further eradication therapy to decrease the risk of metachronous cancer.

After gastrectomy, the cumulative incidence of metachronous cancer is 0.9%–3.0%, irrespective of H. pylori infection[45]. One report investigated the efficacy of eradication therapy for metachronous cancer risk after surgical partial gastric resection[17]. Cho et al[17] reported that eradication for patients after surgical resection is beneficial, as reflected by milder atrophy and intestinal metaplasia at 36 mo after surgery, but did not report any effect on GC. Therefore, although H. pylori in the gastric remnant would be associated with more severe atrophy and intestinal metaplasia over time, the efficacy of eradication therapy in patients with gastric remnants might be limited compared with that in non-GC patients with gastritis and patients after endoscopic gastric resection.

Subgroup analysis by different countries

Significant difference of GC risk after eradication among East Asian countries is shown in this meta-analysis. GC risk is known to depend on combination of bacterial factors (e.g., cagA status and vacA type), the host genetic factors (e.g., inflammatory cytokine genes, detoxification-related genes and oncogenes) and environmental factors (e.g., salt intake, smoking and alcohol)[46-51]. Therefore, the preventive effect for GC after eradication is also expected to depend on above different factors. Because the host genetic factors in East Asian populations (e.g., Japan, South Korea and China) is similar, different life style and different strain of H. pylori may cause difference for GC risk after eradication.

Chemoprevention for non-GC patients with gastritis

In this meta-analysis, although metachronous cancer incidence in H. pylori-positive patients after resection of GC was 2922.0 per 100000 person-years, that in non-GC patients with gastritis was not as high (322.4 per 100000 person-years). In 2001, Uemura et al[52] reported that GCs developed in 2.9% of H. pylori-positive patients at a mean follow-up of 7.8 years, but not in any H. pylori-negative patients or eradicated patients. This startling observation focused attention on the association of GC and H. pylori infection. This meta-analysis showed that 1 study of 4 RCTs (25.0%) and 7 studies of 12 cohort studies (58.3%) in East Asian populations had significant reduction in GC risk, with mean RRs of 0.67 (95%CI: 0.47–0.96) in RCTs and 0.39 (0.30–0.51) in cohort studies, suggesting that eradication for all H. pylori-positive non-GC patients with gastritis will decrease the risk of GC in East Asian populations. Further prospective studies with longer follow-up periods might help clarify the protective effect of H. pylori eradication against GC.

It was shown that the prophylactic effect of H. pylori eradication therapy was not observed in all groups of patients, but only in some ones. Longer follow-up after eradication therapy is associated with better prevention of GC development[53] and significant reduction in cancer incidence after eradication is observed only in pepsinogen test-negative subjects[25]. It may be important to clarify a high-risk group or a risk factor for GC development. A simple and safe method of identifying patients at increased risk of GC is necessary. As possible factors, pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha)[46,54], prostate stem cell antigen gene[55] methylation levels of any genes [e.g., miR-124a-3, empty spiracles homeobox 1 (EMX1) and NK6 homeobox 1 (NKX6-1)][56], and H. pylori virulence factors (e.g. cagA and vacA)[57,58], as well as endoscopic and pathological evidence of atrophy and intestinal metaplasia, have been cited. Ideally, eradication therapy should be instituted prior to the development of atrophy and intestinal metaplasia to achieve the optimal lowering of risk.

Incidence rate of GC after H. pylori eradication therapy between RCTs and cohort studies is the large difference: 272.7 (180.4–322.4) for RCT and 467.2 (68.7–1379.5) per 100000 person-years for cohort studies. This may be caused that patient background in each report is very heterogeneous in age, sex, disease, and severity of gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia. Further study will be required to clarify this problem.

High-efficacy eradication therapy and eradication regimens

In this meta-analysis, as summarized in Table 1, eradication therapy with a regimen including PPI and two kinds of antimicrobial agent (i.e., clarithromycin, amoxicillin, or metronidazole) in the RCTs resulted in eradication rates of 66.2%–88.9% in non-GC patients with gastritis and 75.0%–82.6% in patients after resection. To prevent GC, it is ideal to select an eradication regimen that provides a high eradication rate[59]. Unfortunately, however, because the frequent use of clarithromycin in general clinical situations has led to a global increase in the prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant strains, eradication rates with first-line clarithromycin-containing therapies are decreasing[60,61]. Recently, the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report has recommended quadruple therapy with or without bismuth, and without clarithromycin for patients living in areas with a high prevalence of clarithromycin resistance[62]. The new acid-inhibitory drug vonoprazan that produces rapid, strong and long-lasting gastric acid inhibition after administration of the first tablet in a dose-dependent manner has become clinically available in Japan, and vonoprazan-containing regimens have demonstrated effectiveness in patients infected with clarithromycin-resistant strains and patients living in areas where the prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant strains is > 15%[59,63-65]. As culture-based and pharmaco-genomics-based tailored treatment may have the potential to achieve an eradication rate exceeding 95%, the theoretical advantages of vonoprazan as evidenced by its potent acid inhibition during eradication therapy are considered to expedite risk reduction.

In addition, according to increase of incidence rates of antimicrobial agents-resistant H. pylori strains, patients refractory to eradication therapy including amoxicillin, clarithromycin, nitroimidazoles, fluoroquinolones, bismuth or tetracycline, is expected to be increasing. Recently, possible that use of new antimicrobial agents, such as rifabutin and sitafloxacin, have a potential with high eradication rate are suggested[66,67].

Limitations

We meta-analyzed studies in East Asian populations. Therefore, it is unclear whether this preventive strategy also applies to other populations. Studies investigating efficacy in populations with lower incidence rates of GC are scarce, and more investigation is needed. In addition, this meta-analysis is insufficient to investigate any association of preventive efficacy with patient age at the time of eradication. In an animal model with Mongolian gerbils, eradication therapy was shown to have an association with GC risk and duration of H. pylori infection, and a shorter duration of H. pylori infection due to early eradication was associated with a low risk of GC[68]. Long-term H. pylori infection may result in severe atrophic gastritis with intestinal metaplasia, and the earliest possible implementation of H. pylori eradication therapy is likely important in preventing GC.

In conclusion[17-33,52,53,69-94], this meta-analysis strengthens the evidence for the potential of H. pylori eradication therapy to reduce the risk of GC in East Asian populations with high incidence rates of GC. GC risk is known to depend on combination of bacterial factors (e.g., cagA status and vacA type), the host’s genetic factors (e.g., inflammation-related molecule polymorphism) and environmental factors (e.g., salt and smoking). Of those risk factors, because gastric mucosal change (e.g., gastric mucosal atrophy and intestinal metaplasia) with risk of GC development gradually progress after H pylori infection, best way is to avoid from infection of H. pylori, and if H. pylori infects, eradication therapy should be performed as soon as possible at younger age before progression of gastric mucosal atrophy in all H. pylori positive patients. The surveillance interval in patients after endoscopic and operative resection and non-GC patients with atrophic gastritis is important after eradication therapy. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines state that even for Tis or T1 with N0 lesions achieving R0 with endoscopic and surgical resection, all patients should be followed systematically, and that follow-up should include a complete history and physical examination every 3 to 6 mo for 1 to 2 years, every 6 to 12 mo for 3 to 5 years, and annually thereafter for all patients (http://www.nccn.org/ professionals/physician_gls/PDF/gastric.pdf).

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is a risk factor for gastric cancer (GC), especially in East Asian populations. Most East Asian populations infected with H. pylori are at higher risk for GC than H. pylori-positive European and United States populations. H. pylori eradication therapy reduces GC risk in patients after endoscopic and operative resection for GC, as well as in patients with atrophic gastritis. However, it remains unclear whether eradication therapy exerts the same chemopreventive effect on GC among different groups, e.g., those of different nationalities, those with a history of gastritis alone, those with a prior history of GC resection, etc., with different risk levels for GC development.

Research motivation

We hope to up-date evidences for preventive effect on development of GC after eradication therapy in East Asian populations.

Research objectives

To clarify the preventive effects of H. pylori eradication therapy for development of GC in an East Asian population with a high incidence of GC.

Research methods

PubMed and the Cochrane Library were searched for randomized control trials (RCTs) and cohort studies published in English up to March 2019 using the terms “H. pylori,” “GC,” and “eradication therapy”. Subgroup analyses were conducted with regard to study designs (i.e., RCTs or cohort studies), country where the study was conducted (i.e., Japan, China, and South Korea), and observation periods (i.e., ≤ 5 years and > 5 years). The heterogeneity and publication bias were also measured.

Research results

For patients with atrophic gastritis alone and patients after resection for GC, 4 and 4 RCTs and 12 and 18 cohort studies were included, respectively. In RCTs, the median incidence of GC for the untreated control groups and the treatment groups in cases of gastritis alone was 272.7 (180.4–322.4) and 162.3 (72.5–588.2) per 100000 person-years. In RCTs, the median incidence of metachronous GC for the untreated control groups and the treatment groups was 1790.7 (406.5–2941.2) and 1126.2 (678.7–1223.1) per 100000 person-years. Compared with non-treated H. pylori-positive controls, the eradication groups had a significantly reduced risk of GC, with a relative risk of 0.67 [95% confidence interval: 0.47–0.96] for patients with atrophic gastritis alone and 0.51 (0.36–0.73) for patients after resection for GC in the RCTs and 0.39 (0.30–0.51) and 0.54 (0.44–0.67) in cohort studies.

Research conclusions

The current meta-analysis showed that in the East Asian population with high incidence rates of GC, H. pylori eradication effectively reduced the risk of GC, irrespective of past history of previous cancer. The surveillance interval in patients after endoscopic and operative resection and patients with atrophic gastritis alone is important after eradication therapy.

Research perspectives

The results of the current meta-analysis may offer gastroenterologists and endoscopists more reliable evidence in efficacy of H. pylori eradication therapy and importance of surveillance after eradication therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Hitomi Mizuno, MD, PhD for checking data of each study and editing the paper.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors deny any conflict of interest.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: This study was conducted according to the PRISMA agreement reporting guidelines.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: December 16, 2019

First decision: January 7, 2020

Article in press: April 1, 2020

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Durazzo M, Grotz TE, Senchukova M S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Mitsushige Sugimoto, Department of Gastroenterological Endoscopy, Tokyo Medical University Hospital, Sinjuku, Tokyo 1600023, Japan. sugimo@tokyo-med.ac.jp.

Masaki Murata, Department of Gastroenterology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, Kyoto 6128555, Japan.

Yoshio Yamaoka, Department of Gastroenterology, Department of Environmental and Preventive Medicine, Oita University Faculty of Medicine, Yufu, Oita 8795593, Japan.

References

- 1.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, Chang Y, Vogelman JH, Orentreich N, Sibley RK. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, 7-14 June 1994. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. 1994;61:1–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori infection in the pathogenesis of duodenal ulcer and gastric cancer: a model. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1983–1991. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugimoto M, Ban H, Ichikawa H, Sahara S, Otsuka T, Inatomi O, Bamba S, Furuta T, Andoh A. Efficacy of the Kyoto Classification of Gastritis in Identifying Patients at High Risk for Gastric Cancer. Intern Med. 2017;56:579–586. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.56.7775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161–1181. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rugge M, Correa P, Di Mario F, El-Omar E, Fiocca R, Geboes K, Genta RM, Graham DY, Hattori T, Malfertheiner P, Nakajima S, Sipponen P, Sung J, Weinstein W, Vieth M. OLGA staging for gastritis: a tutorial. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:650–658. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rugge M, Meggio A, Pennelli G, Piscioli F, Giacomelli L, De Pretis G, Graham DY. Gastritis staging in clinical practice: the OLGA staging system. Gut. 2007;56:631–636. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.106666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugimoto M, Yamaoka Y. The association of vacA genotype and Helicobacter pylori-related disease in Latin American and African populations. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:835–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02769.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugimoto M, Zali MR, Yamaoka Y. The association of vacA genotypes and Helicobacter pylori-related gastroduodenal diseases in the Middle East. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:1227–1236. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0772-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamaoka Y, Kodama T, Gutierrez O, Kim JG, Kashima K, Graham DY. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori iceA, cagA, and vacA status and clinical outcome: studies in four different countries. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2274–2279. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2274-2279.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamaoka Y, Kikuchi S, el-Zimaity HM, Gutierrez O, Osato MS, Graham DY. Importance of Helicobacter pylori oipA in clinical presentation, gastric inflammation, and mucosal interleukin 8 production. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:414–424. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaoka Y, Orito E, Mizokami M, Gutierrez O, Saitou N, Kodama T, Osato MS, Kim JG, Ramirez FC, Mahachai V, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori in North and South America before Columbus. FEBS Lett. 2002;517:180–184. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02617-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamaoka Y, El-Zimaity HM, Gutierrez O, Figura N, Kim JG, Kodama T, Kashima K, Graham DY. Relationship between the cagA 3' repeat region of Helicobacter pylori, gastric histology, and susceptibility to low pH. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:342–349. doi: 10.1053/gast.1999.0029900342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kodama M, Murakami K, Okimoto T, Sato R, Uchida M, Abe T, Shiota S, Nakagawa Y, Mizukami K, Fujioka T. Ten-year prospective follow-up of histological changes at five points on the gastric mucosa as recommended by the updated Sydney system after Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:394–403. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T, El-Omar EM, Kuipers EJ European Helicobacter Study Group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asaka M, Kato M, Takahashi S, Fukuda Y, Sugiyama T, Ota H, Uemura N, Murakami K, Satoh K, Sugano K Japanese Society for Helicobacter Research. Guidelines for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan: 2009 revised edition. Helicobacter. 2010;15:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho SJ, Choi IJ, Kook MC, Yoon H, Park S, Kim CG, Lee JY, Lee JH, Ryu KW, Kim YW. Randomised clinical trial: the effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on glandular atrophy and intestinal metaplasia after subtotal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:477–489. doi: 10.1111/apt.12402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, Chen JS, Zheng TT, Feng RE, Lai KC, Hu WH, Yuen ST, Leung SY, Fong DY, Ho J, Ching CK, Chen JS China Gastric Cancer Study Group. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187–194. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong BC, Zhang L, Ma JL, Pan KF, Li JY, Shen L, Liu WD, Feng GS, Zhang XD, Li J, Lu AP, Xia HH, Lam S, You WC. Effects of selective COX-2 inhibitor and Helicobacter pylori eradication on precancerous gastric lesions. Gut. 2012;61:812–818. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YC, Chen TH, Chiu HM, Shun CT, Chiang H, Liu TY, Wu MS, Lin JT. The benefit of mass eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection: a community-based study of gastric cancer prevention. Gut. 2013;62:676–682. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shichijo S, Hirata Y, Sakitani K, Yamamoto S, Serizawa T, Niikura R, Watabe H, Yoshida S, Yamada A, Yamaji Y, Ushiku T, Fukayama M, Koike K. Distribution of intestinal metaplasia as a predictor of gastric cancer development. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1260–1264. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito K, Arai K, Mori M, Kobayashi R, Ohki I. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on malignant transformation of gastric adenoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:27–32. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.106112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma JL, Zhang L, Brown LM, Li JY, Shen L, Pan KF, Liu WD, Hu Y, Han ZX, Crystal-Mansour S, Pee D, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF, Jr, You WC, Gail MH. Fifteen-year effects of Helicobacter pylori, garlic, and vitamin treatments on gastric cancer incidence and mortality. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:488–492. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou L, Lin S, Ding S, Huang X, Jin Z, Cui R, Meng L, Li Y, Zhang L, Guo C, Xue Y, Yan X, Zhang J. Relationship of Helicobacter pylori eradication with gastric cancer and gastric mucosal histological changes: a 10-year follow-up study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2014;127:1454–1458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yanaoka K, Oka M, Ohata H, Yoshimura N, Deguchi H, Mukoubayashi C, Enomoto S, Inoue I, Iguchi M, Maekita T, Ueda K, Utsunomiya H, Tamai H, Fujishiro M, Iwane M, Takeshita T, Mohara O, Ichinose M. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori prevents cancer development in subjects with mild gastric atrophy identified by serum pepsinogen levels. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2697–2703. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watanabe M, Kato J, Inoue I, Yoshimura N, Yoshida T, Mukoubayashi C, Deguchi H, Enomoto S, Ueda K, Maekita T, Iguchi M, Tamai H, Utsunomiya H, Yamamichi N, Fujishiro M, Iwane M, Tekeshita T, Mohara O, Ushijima T, Ichinose M. Development of gastric cancer in nonatrophic stomach with highly active inflammation identified by serum levels of pepsinogen and Helicobacter pylori antibody together with endoscopic rugal hyperplastic gastritis. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2632–2642. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung S, Park CH, Kim EH, Shin SJ, Chung H, Lee H, Park JC, Shin SK, Lee YC, Lee SK. Preventing metachronous gastric lesions after endoscopic submucosal dissection through Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:75–81. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim JH, Kim SG, Choi J, Im JP, Kim JS, Jung HC. Risk factors of delayed ulcer healing after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:3666–3673. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4123-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwon Y, Jeon S, Nam S, Shin I. Helicobacter pylori infection and serum level of pepsinogen are associated with the risk of metachronous gastric neoplasm after endoscopic resection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:758–767. doi: 10.1111/apt.14263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung CS, Woo HS, Chung JW, Jeong SH, Kwon KA, Kim YJ, Kim KO, Park DK. Risk Factors for Metachronous Recurrence after Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection of Early Gastric Cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32:421–426. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.3.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukase K, Kato M, Kikuchi S, Inoue K, Uemura N, Okamoto S, Terao S, Amagai K, Hayashi S, Asaka M Japan Gast Study Group. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:392–397. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi IJ, Kook MC, Kim YI, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, Park B, Nam BH. Helicobacter pylori Therapy for the Prevention of Metachronous Gastric Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1085–1095. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi JM, Kim SG, Choi J, Park JY, Oh S, Yang HJ, Lim JH, Im JP, Kim JS, Jung HC. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication for metachronous gastric cancer prevention: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88:475–485.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon SB, Park JM, Lim CH, Cho YK, Choi MG. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of gastric tumors: a meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2014;19:243–248. doi: 10.1111/hel.12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao S, Li S, Zhou L, Jiang W, Liu J. Helicobacter pylori status and risks of metachronous recurrence after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:226–237. doi: 10.1007/s00535-018-1513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugano K. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the incidence of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22:435–445. doi: 10.1007/s10120-018-0876-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsuda M, Asaka M, Kato M, Matsushima R, Fujimori K, Akino K, Kikuchi S, Lin Y, Sakamoto N. Effect on Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy against gastric cancer in Japan. Helicobacter. 2017:22. doi: 10.1111/hel.12415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim SH, Kwon JW, Kim N, Kim GH, Kang JM, Park MJ, Yim JY, Kim HU, Baik GH, Seo GS, Shin JE, Joo YE, Kim JS, Jung HC. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: nationwide multicenter study over 13 years. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jun JK, Choi KS, Lee HY, Suh M, Park B, Song SH, Jung KW, Lee CW, Choi IJ, Park EC, Lee D. Effectiveness of the Korean National Cancer Screening Program in Reducing Gastric Cancer Mortality. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1319–1328.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nashimoto A, Akazawa K, Isobe Y, Miyashiro I, Katai H, Kodera Y, Tsujitani S, Seto Y, Furukawa H, Oda I, Ono H, Tanabe S, Kaminishi M. Gastric cancer treated in 2002 in Japan: 2009 annual report of the JGCA nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10120-012-0163-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugimoto M, Jang JS, Yoshizawa Y, Osawa S, Sugimoto K, Sato Y, Furuta T. Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy before and after Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection: A Review. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2012;2012:791873. doi: 10.1155/2012/791873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gotoda T, Yamamoto H, Soetikno RM. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:929–942. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1954-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Nimura S, Yahagi N, Iishi H, Oka M, Ajioka Y, Ichinose M, Matsui T. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:3–15. doi: 10.1111/den.12518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fujishiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for stomach neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5108–5112. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i32.5108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abe S, Oda I, Minagawa T, Sekiguchi M, Nonaka S, Suzuki H, Yoshinaga S, Bhatt A, Saito Y. Metachronous Gastric Cancer Following Curative Endoscopic Resection of Early Gastric Cancer. Clin Endosc. 2018;51:253–259. doi: 10.5946/ce.2017.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.El-Omar EM, Carrington M, Chow WH, McColl KE, Bream JH, Young HA, Herrera J, Lissowska J, Yuan CC, Rothman N, Lanyon G, Martin M, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Rabkin CS. Interleukin-1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of gastric cancer. Nature. 2000;404:398–402. doi: 10.1038/35006081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El-Omar EM, Rabkin CS, Gammon MD, Vaughan TL, Risch HA, Schoenberg JB, Stanford JL, Mayne ST, Goedert J, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Chow WH. Increased risk of noncardia gastric cancer associated with proinflammatory cytokine gene polymorphisms. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1193–1201. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sugimoto M, Furuta T, Shirai N, Nakamura A, Kajimura M, Sugimura H, Hishida A, Ishizaki T. Poor metabolizer genotype status of CYP2C19 is a risk factor for developing gastric cancer in Japanese patients with Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:1033–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suzuki S, Muroishi Y, Nakanishi I, Oda Y. Relationship between genetic polymorphisms of drug-metabolizing enzymes (CYP1A1, CYP2E1, GSTM1, and NAT2), drinking habits, histological subtypes, and p53 gene point mutations in Japanese patients with gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:220–230. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu H, Hsu PI, Graham DY, Yamaoka Y. Duodenal ulcer promoting gene of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:833–848. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamaoka Y, Ojo O, Fujimoto S, Odenbreit S, Haas R, Gutierrez O, El-Zimaity HM, Reddy R, Arnqvist A, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori outer membrane proteins and gastroduodenal disease. Gut. 2006;55:775–781. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.083014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mabe K, Takahashi M, Oizumi H, Tsukuma H, Shibata A, Fukase K, Matsuda T, Takeda H, Kawata S. Does Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy for peptic ulcer prevent gastric cancer? World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4290–4297. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sugimoto M, Furuta T, Shirai N, Nakamura A, Xiao F, Kajimura M, Sugimura H, Hishida A. Different effects of polymorphisms of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1 beta on development of peptic ulcer and gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:51–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ichikawa H, Sugimoto M, Uotani T, Sahara S, Yamade M, Iwaizumi M, Yamada T, Osawa S, Sugimoto K, Miyajima H, Yamaoka Y, Furuta T. Influence of prostate stem cell antigen gene polymorphisms on susceptibility to Helicobacter pylori-associated diseases: a case-control study. Helicobacter. 2015;20:106–113. doi: 10.1111/hel.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Asada K, Nakajima T, Shimazu T, Yamamichi N, Maekita T, Yokoi C, Oda I, Ando T, Yoshida T, Nanjo S, Fujishiro M, Gotoda T, Ichinose M, Ushijima T. Demonstration of the usefulness of epigenetic cancer risk prediction by a multicentre prospective cohort study. Gut. 2015;64:388–396. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sugimoto M, Yamaoka Y. Virulence factor genotypes of Helicobacter pylori affect cure rates of eradication therapy. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2009;57:45–56. doi: 10.1007/s00005-009-0007-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamaoka Y, Kita M, Kodama T, Sawai N, Imanishi J. Helicobacter pylori cagA gene and expression of cytokine messenger RNA in gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1744–1752. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8964399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sugimoto M, Yamaoka Y. Role of Vonoprazan in Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapy in Japan. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1560. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Asaka M, Sugiyama T, Kato M, Satoh K, Kuwayama H, Fukuda Y, Fujioka T, Takemoto T, Kimura K, Shimoyama T, Shimizu K, Kobayashi S. A multicenter, double-blind study on triple therapy with lansoprazole, amoxicillin and clarithromycin for eradication of Helicobacter pylori in Japanese peptic ulcer patients. Helicobacter. 2001;6:254–261. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2001.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murakami K, Sato R, Okimoto T, Nasu M, Fujioka T, Kodama M, Kagawa J, Sato S, Abe H, Arita T. Eradication rates of clarithromycin-resistant Helicobacter pylori using either rabeprazole or lansoprazole plus amoxicillin and clarithromycin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1933–1938. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A, Atherton J, Graham DY, Hunt R, Moayyedi P, Rokkas T, Rugge M, Selgrad M, Suerbaum S, Sugano K, El-Omar EM European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group and Consensus panel. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017;66:6–30. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jenkins H, Sakurai Y, Nishimura A, Okamoto H, Hibberd M, Jenkins R, Yoneyama T, Ashida K, Ogama Y, Warrington S. Randomised clinical trial: safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of repeated doses of TAK-438 (vonoprazan), a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, in healthy male subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:636–648. doi: 10.1111/apt.13121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sakurai Y, Mori Y, Okamoto H, Nishimura A, Komura E, Araki T, Shiramoto M. Acid-inhibitory effects of vonoprazan 20 mg compared with esomeprazole 20 mg or rabeprazole 10 mg in healthy adult male subjects--a randomised open-label cross-over study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:719–730. doi: 10.1111/apt.13325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kagami T, Sahara S, Ichikawa H, Uotani T, Yamade M, Sugimoto M, Hamaya Y, Iwaizumi M, Osawa S, Sugimoto K, Miyajima H, Furuta T. Potent acid inhibition by vonoprazan in comparison with esomeprazole, with reference to CYP2C19 genotype. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:1048–1059. doi: 10.1111/apt.13588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ribaldone DG, Fagoonee S, Astegiano M, Durazzo M, Morgando A, Sprujevnik T, Giordanino C, Baronio M, De Angelis C, Saracco GM, Pellicano R. Rifabutin-Based Rescue Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Eradication: A Long-Term Prospective Study in a Large Cohort of Difficult-to-Treat Patients. J Clin Med. 2019:8. doi: 10.3390/jcm8020199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sugimoto M, Sahara S, Ichikawa H, Kagami T, Uotani T, Furuta T. High Helicobacter pylori cure rate with sitafloxacin-based triple therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:477–483. doi: 10.1111/apt.13280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nozaki K, Shimizu N, Ikehara Y, Inoue M, Tsukamoto T, Inada K, Tanaka H, Kumagai T, Kaminishi M, Tatematsu M. Effect of early eradication on Helicobacter pylori-related gastric carcinogenesis in Mongolian gerbils. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:235–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choi J, Kim SG, Yoon H, Im JP, Kim JS, Kim WH, Jung HC. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori after endoscopic resection of gastric tumors does not reduce incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:793–800.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Uemura N, Mukai T, Okamoto S, Yamaguchi S, Mashiba H, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Haruma K, Sumii K, Kajiyama G. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on subsequent development of cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:639–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nakagawa S, Asaka M, Kato M, Nakamura T, Kato C, Fujioka T, Tatsuta M, Keida K, Terao S, Takahishi S, Uemura N, Kato T, Aiyama N, Saito D, Ssuzuki M, Imamura A, Sato K, Miwa H, Nomura H, Kaise M, Oohara S, Kawai T, Urabe K, Sakaki N, Ito S, Noda Y, Yanaka A, Kusugami K, Goto H, Furuta T, Fujino M, Kinjyo F, Ookusa T. Helicobacter pylori eradication and metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic mucosal resection of early gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:214–218. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shiotani A, Uedo N, Iishi H, Yoshiyuki Y, Ishii M, Manabe N, Kamada T, Kusunoki H, Hata J, Haruma K. Predictive factors for metachronous gastric cancer in high-risk patients after successful Helicobacter pylori eradication. Digestion. 2008;78:113–119. doi: 10.1159/000173719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Han JS, Jang JS, Choi SR, Kwon HC, Kim MC, Jeong JS, Kim SJ, Sohn YJ, Lee EJ. A study of metachronous cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1099–1104. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.591427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim H, Hong S, Ko B, Cho W, Cho J, Lee J, Lee M. Helicobacter pylori eradication suppresses metachronous gastric cancer and cyclooxygenase-2 expression after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Korean J Helicobacter Up Gastrointest Res. 2011;11:117–123. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maehata Y, Nakamura S, Fujisawa K, Esaki M, Moriyama T, Asano K, Fuyuno Y, Yamaguchi K, Egashira I, Kim H, Kanda M, Hirahashi M, Matsumoto T. Long-term effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the development of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Seo JY, Lee DH, Cho Y, Lee DH, Oh HS, Jo HJ, Shin CM, Lee SH, Park YS, Hwang JH, Kim JW, Jeong SH, Kim N, Jung HC, Song IS. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori reduces metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:776–780. doi: 10.5754/hge12929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kato M, Nishida T, Yamamoto K, Hayashi S, Kitamura S, Yabuta T, Yoshio T, Nakamura T, Komori M, Kawai N, Nishihara A, Nakanishi F, Nakahara M, Ogiyama H, Kinoshita K, Yamada T, Iijima H, Tsujii M, Takehara T. Scheduled endoscopic surveillance controls secondary cancer after curative endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: a multicentre retrospective cohort study by Osaka University ESD study group. Gut. 2013;62:1425–1432. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bae SE, Jung HY, Kang J, Park YS, Baek S, Jung JH, Choi JY, Kim MY, Ahn JY, Choi KS, Kim DH, Lee JH, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH, Kim JH. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on metachronous recurrence after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasm. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:60–67. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kim YI, Choi IJ, Kook MC, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, Ryu KW, Kim YW. The association between Helicobacter pylori status and incidence of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Helicobacter. 2014;19:194–201. doi: 10.1111/hel.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kwon YH, Heo J, Lee HS, Cho CM, Jeon SW. Failure of Helicobacter pylori eradication and age are independent risk factors for recurrent neoplasia after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer in 283 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:609–618. doi: 10.1111/apt.12633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim SB, Lee SH, Bae SI, Jeong YH, Sohn SH, Kim KO, Jang BI, Kim TN. Association between Helicobacter pylori status and metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:9794–9802. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i44.9794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ami R, Hatta W, Iijima K, Koike T, Ohkata H, Kondo Y, Ara N, Asanuma K, Asano N, Imatani A, Shimosegawa T. Factors Associated With Metachronous Gastric Cancer Development After Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastric Cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:494–499. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Han SJ, Kim SG, Lim JH, Choi JM, Oh S, Park JY, Kim J, Kim JS, Jung HC. Long-Term Effects of Helicobacter pylori Eradication on Metachronous Gastric Cancer Development. Gut Liver. 2018;12:133–141. doi: 10.5009/gnl17073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.You WC, Brown LM, Zhang L, Li JY, Jin ML, Chang YS, Ma JL, Pan KF, Liu WD, Hu Y, Crystal-Mansour S, Pee D, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Xu GW, Gail MH. Randomized double-blind factorial trial of three treatments to reduce the prevalence of precancerous gastric lesions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:974–983. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li WQ, Ma JL, Zhang L, Brown LM, Li JY, Shen L, Pan KF, Liu WD, Hu Y, Han ZX, Crystal-Mansour S, Pee D, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF, Jr, You WC, Gail MH. Effects of Helicobacter pylori treatment on gastric cancer incidence and mortality in subgroups. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014:106. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Leung WK, Lin SR, Ching JY, To KF, Ng EK, Chan FK, Lau JY, Sung JJ. Factors predicting progression of gastric intestinal metaplasia: results of a randomised trial on Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gut. 2004;53:1244–1249. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.034629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kato M, Asaka M, Nakamura T, Azuma T, Tomita E, Kamoshida T, Sato K, Inaba T, Shirasaki D, Okamoto S, Takahashi S, Terao S, Suwaki K, Isomoto H, Yamagata H, Nomura S, Yagi K, Sone Y, Urabe T, Akamatsu T, Ohara S, Takagi A, Miwa J, Inatsuchi S. Helicobacter pylori eradication prevents the development of gastric cancer - results of a long-term retrospective study in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:203–206. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Takenaka R, Okada H, Kato J, Makidono C, Hori S, Kawahara Y, Miyoshi M, Yumoto E, Imagawa A, Toyokawa T, Sakaguchi K, Shiratori Y. Helicobacter pylori eradication reduced the incidence of gastric cancer, especially of the intestinal type. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:805–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ogura K, Hirata Y, Yanai A, Shibata W, Ohmae T, Mitsuno Y, Maeda S, Watabe H, Yamaji Y, Okamoto M, Yoshida H, Kawabe T, Omata M. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on reducing the incidence of gastric cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:279–283. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000248006.80699.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim N, Park RY, Cho SI, Lim SH, Lee KH, Lee W, Kang HM, Lee HS, Jung HC, Song IS. Helicobacter pylori infection and development of gastric cancer in Korea: long-term follow-up. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:448–454. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318046eac3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Hamada F, Yoshida T, Yokota K, Okada H, Yamamoto K. Seventeen-year effects of eradicating Helicobacter pylori on the prevention of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer; a prospective cohort study. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:638–644. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-1004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Yoshida T, Ohara N, Yokota K, Oguma K, Okada H, Yamamoto K. The long-term risk of gastric cancer after the successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:318–324. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0347-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Nagahara Y, Yoshida T, Yokota K, Oguma K. Baseline gastric mucosal atrophy is a risk factor associated with the development of gastric cancer after Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in patients with peptic ulcer diseases. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42 Suppl 17:21–27. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1924-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]