Abstract

Cooperative kidney paired donation (KPD) networks account for an increasing proportion of all living donor kidney transplants in the United States. There is sparse data on the rate of primary non-function (PNF) losses and their consequences within KPD networks. We studied National Kidney Registry (NKR) transplants (2/14/2009–12/31/2017) and quantified PNF, graft loss within 30 days of transplantation, and graft losses in the first year post-transplant and assessed potential risk factors. Of 2364 transplants, there were 38 (1.6%) grafts lost within the first year, 13 (0.5%) with PNF. When compared to functioning grafts, there were no clinically significant differences in blood type compatibility, degree of HLA mismatch, number of veins/arteries, cold ischemia, and travel times. Of 13 PNF cases, 2 were due to early venous thrombosis, 2 to arterial thrombosis, and 2 to failure of desensitization and development of AMR. Given the low rate of PNF, the NKR created a policy to allocate chain-end kidneys to recipients with PNF following event review and attributable to surgical issues of donor nephrectomy. It is expected that demonstration of low incidence of poor early graft outcomes and the presence of a ‘safety net’ would further encourage program participation in national KPD.

INTRODUCTION

Kidney paired donation (KPD) has seen consistent growth over the last two decades (1). Although some single center systems have seen modest growth (2, 3), regional and national systems currently account for the majority of KPD transplants in the United States (4, 5). These cooperative networks require a great deal of trust between different teams of surgeons, nephrologists, nurses, donor advocates, social workers, and living donor coordinators responsible for the preoperative evaluation of donors, as well as kidney quality resulting from the performance of the donor nephrectomy. While deceased donor kidneys are routinely procured by remote centers, living donor organs are procuded by a program’s own surgeons; this was especially true prior to the establishment of large KPD systems (6). Programs depend upon cooperation between transplant centers and teams, and necessitate trust in the quality of donor procurements at other centers. As evidenced in a recent debate at the 2019 ASTS Winter Symposium titled, “Trust or Fly: We Need to Procure Organ for Each Other,” there is still a tendency for many centers to only want to rely on their own surgeons.

Participation in national exchange programs challenges this preference. Medium and long-term graft survival for these transplants are high, which is expected of living donor kidney transplantation even in the context of longer KPD cold ischemic times (4, 7, 8). However, scarce data exist on primary non-function (PNF or loss within 30 days of transplant), other early graft failures, and surgical complications that may continue to cause a reluctance by many transplant centers to enter larger multicenter, diverse geographical KPD systems.

The National Kidney Registry (NKR) is a KPD network that facilitates live donor transplants between 85 participating centers (5, 9, 10). The NKR’s core functions include outlining protocols for evaluating patients, creating matches to maximize the number of transplants according to established computerized algorithms, arranging transport between centers, and organizing the collection of follow-up data. The participating transplant centers complete all transplants in concordance with UNOS and center-specific protocols. The ultimate goal is increasing the number of transplants for incompatible or difficult to match pairs. The number of transplants facilitated by the NKR has grown annually since its inception in 2008 (11). As the NKR evolved, it became apparent that kidneys, rather than donors, would travel from one center to another. In the beginning, there was great trepidation about the negative impact of longer cold ischemic times imposed by shipping, especially for highly sensitized and retransplanted patients (6, 12–14). However, reports that demonstrated a slight increase in DGF but no impact on graft or patient survival encouraged wider sharing and allowed for cold ischemia times that exceed 20 hours (7, 8). These reports focus on long term outcomes, but little has been reported on the occurrences of graft failures within days or months of transplantation.

When an early graft failure occurs, the recipient is left both without a functioning kidney and perhaps their only donor having already undergone a donor nephrectomy. Following PNF, KPD pairs may be left questioning their decisions around donation, particularly if they were a compatible pair that voluntarily entered the exchange. Without additional potential donors, the recipient may be limited to retransplantation on the deceased donor list. Trust in living donor transplantation and KPD may erode between the recipient, the family, the transplant center, as well as the other participating KPD centers (6). The aim of this study was to focus on quantifying the risk of early graft loss and to identify potential risk factors within the NKR system, including, and especially, surgical complications during the donor nephrectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The National Kidney Registry

Data was collected from the NKR registry, which receives regular updates from participating transplant centers. The clinical and research activities of this study are consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki and Declaration of Istanbul. Using the NKR registry, we identified 2,454 living donor kidney transplants (LDKTs) facilitated by the NKR between February 2008 and December 2017 with complete 1-year follow-up.

National Registry

In addition to NKR registry data, this study also used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) external release made available in March 2019. The SRTR data system includes data on all donors, waitlist candidates, and transplant recipients in the US, submitted by members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), and has been previously described (15). The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors. All recipients were followed for post-transplant outcomes through December 31, 2018. We include 49,864 non-KPD living donor kidney transplant recipients as controls.

Data Linkage

Data on KPD transplants facilitated by the NKR were linked to the SRTR using unique, encrypted, person-level identifiers; they were cross-validated using redundantly captured characteristics (transplant center, transplant date, donor blood type, donor sex, recipient blood type, and recipient sex). As a result of linkage and cross-validation, 2,364 (96%) LDKT facilitated by the NKR were included in the study population. Those that did not cross-validate were transplanted more recently and, thus, failed to link due to reporting lag between transplant centers, SRTR, and NKR.

Statistical Analysis

The members of the study population were followed for a minimum of one-year post-transplant (i.e. earliest transplant date was one year before administrative censoring). We estimate the risk of death-censored graft failure defined as the earliest resumption of maintenance dialysis, relisting for kidney transplant, or retransplantation. Graft failure was assessed by transplant center report to the OPTN supplemented by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Form 2728. Potential risk factors (delayed graft function, preemptive transplant, donor sex, donor race, donor anatomy, cold ischemia time>8 hours, blood type, and HLA mismatch) were evaluated using multivariable linear risk regression to estimate risk differences (RDs) and 95% confidence intervals. Regression models used inverse probability of treatment weights account for recipient factors (age, sex, African-American race, BMI, college education, public insurance, history of previous transplant, and PRA>80). We conducted 15 independent tests, resulting in Bonferroni corrected critical p-value of 0.003. All analyses were performed using Stata 15/MP for Linux (College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Study Population

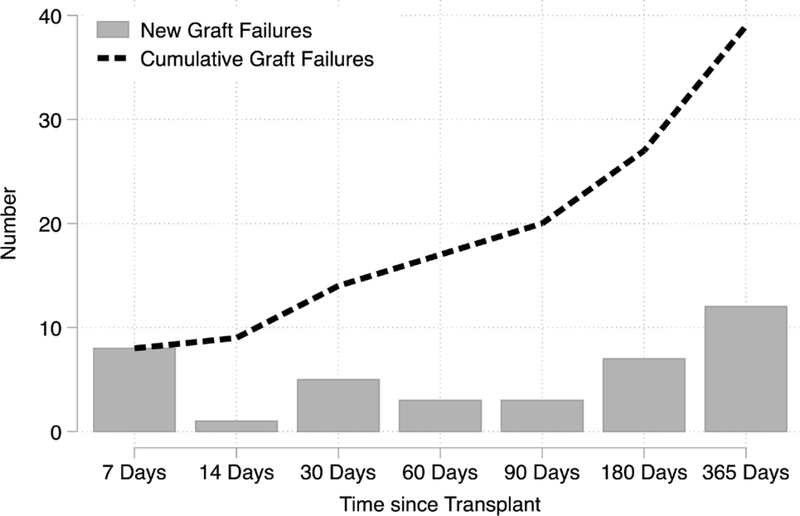

During the study period, the risk of PNF was 0.5% (n=13), and the 1-year graft failure risk was 1.6% (n=38) (Figure 1). The risk of graft failure was not constant throughout the first year. There were 7 failures within 1 week, but only 1 additional failure between 8 and 14 days post-transplant. A simliar trend was seen among SRTR controls. Among the 13 recipients that experienced PNF, 46% were female, 8% were African American, the median age was 55 years, and 31% had PRA>80%. Compared to those with immediate function, PNF recipients did not have clinically significant differences in recipient, donor, and transplant characteristics (Table 1). Inferences were similar comparing those with a graft loss ≤180 days compared to those without a graft loss ≤180 days (Supplemental Table 1) and comparing those with a graft loss within a year to those without a graft loss (Supplemental Table 2). After adjustment for recipient characteristics, delayed graft function (RD=0.074, 95% CI: 0.009–0.139) and donor female sex (RD=0.006, 95% CI: 0.001–0.011) were associated with a higher risk of early graft failure; these results were not statistically significant after correction for multiple comparisons (Table 2).

Figure 1. Cumulative Number of Early Graft Failures in the National Kidney Registry (2008–2017).

Of the 2,364 NKR-facilitated living donor transplant recipients, 38 experienced graft failure within a year. There were 7 that experienced primary non-function (PNF) within 7 days of transplant of a total 13 PNF cases. Half (19 of 38) the early graft failures occurred between 3 and 12 months post-transplant.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 2,364 living donor kidney transplant (KT) facilitated by the National Kidney Registry (NKR) and SRTR controls 2008–2017 by graft loss ≤ 30 days post-transplant.

| NKR | NKR | SRTR Control2 | SRTR Control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Loss ≤ 30 Days | DCGF ≤ 30 Day | No Loss ≤ 30 Days | DCGF ≤ 30 Day | |

| N | 2351 (99.5%) | 13 (0.5%) | 49463 (99.2%) | 401 (0.8%) |

| Recipient Characteristics1 | ||||

| Female | 46 | 46 | 37 | 47 |

| African-American | 18 | 8 | 13 | 16 |

| Age (years) | 51 (39–60) | 55 (37–60) | 49 (36–59) | 46 (34–56) |

| Preemptive Transplant | 25 | 23 | 36 | 39.7 |

| Years on Dialysis | 1 (0–3) | 2 (0–4) | 1 (0–2) | 0.4 (0–1) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27 (23–31) | 28 (25–33) | 27 (24–31) | 28 (24–33) |

| College Educated | 65 | 82 | 60 | 61 |

| Public Insurance | 50 | 62 | 42 | 42 |

| Diabetes | 19 | 8 | 21 | 16 |

| Hypertension | 16 | 15 | 16 | 15 |

| HIV | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Previous Transplant | 25 | 31 | 11 | 12 |

| PRA>80 at Transplant | 21 | 31 | 3 | 5 |

| Antibody Depleting Induction | 66 | 58 | 61 | 69 |

| Antibody Non-Depleting Induction | 30 | 42 | 30 | 30 |

| eGFR Pre-transplant (mL/min/1.7m2) | 8 (6–12) | 8 (5–16) | 9 (6–13) | 10 (6–14) |

| Delayed Graft Function | 5 | 62 | 3 | 57 |

| Donor Characteristics | ||||

| Female | 62 | 85 | 62 | 65 |

| African-American | 10 | 8 | 11 | 15 |

| Age (years) | 45 (35–53) | 42 (37–57) | 42 (33–51) | 42 (33–52) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26 (23–29) | 25 (23–29) | 26.7 (23.8–29.7) | 27 (24–30) |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.7m2) | 98 (86–109) | 94 (79–101) | 100 (87–112) | 100 (88–112) |

| Blood Type A | 30 | 46 | 24 | 25 |

| Blood Type A1 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Blood Type A2 | 2 | 8 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Blood Type AB | 4 | 0 | 0.8 | 1 |

| Blood Type B | 17 | 23 | 7 | 10 |

| Blood Type O | 39 | 23 | 66 | 62 |

| 1 Renal Vein | 83 | 92 | ND3 | ND |

| 2 Renal Veins | 4 | 8 | ND | ND |

| 1 Renal Artery | 68 | 77 | ND | ND |

| 2 Renal Arteries | 18 | 23 | ND | ND |

| Transplant Characteristics | ||||

| ABO Incompatible | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Zero HLA mismatch | 1 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| 1 HLA mismatch | 2 | 0 | 5 | 6 |

| 2 HLA mismatch | 6 | 8 | 16 | 20 |

| 3 HLA mismatch | 16 | 31 | 27 | 24 |

| 4 HLA mismatch | 26 | 39 | 15 | 17 |

| 5 HLA mismatch | 33 | 8 | 18 | 19 |

| 6 HLA mismatch | 15 | 8 | 10 | 7 |

| Cold Ischemia Time (hours) | 9 (6–12) | 9 (6–12) | 1 (0.7–2) | 1 (0.8–2) |

Characteristics are presented as percentages for binary variables and median (25 percentile - 75 percentile) for continuous variables.

SRTR controls are non-KPD (NKR or another system) living donor kidney transplant recipients

Not determined since information not available in SRTR.

Table 2.

Risk factors for early graft loss (within 30 days) in the National Kidney Registry.

| Risk Factor | RD 95% CI | p1 |

|---|---|---|

| Delayed Graft Function | 0.0742 (0.0093–0.1391) | 0.02 |

| Preemptive Transplant | 0.0013 (−0.0060–0.0086) | 0.7 |

| Donor Female | 0.0061 (0.0010–0.0113) | 0.02 |

| Donor African-American | 0.0005 (−0.0108–0.0117) | 0.9 |

| 1 Renal Vein | −0.0048 (−0.0250–0.0153) | 0.6 |

| 2 Renal Veins | 0.0137 (−0.0241–0.0515) | 0.5 |

| 1 Renal Artery | −0.0016 (−0.0100–0.0068) | 0.7 |

| 2 Renal Arteries | 0.0033 (−0.0071–0.0136) | 0.5 |

| CIT>8 hours | 0.0034 (−0.0021–0.0089) | 0.2 |

| Blood Type A vs. O | 0.0028 (−0.0046–0.0101) | 0.5 |

| Blood Type A1 vs. O | ND2 | ND |

| Blood Type A2 vs. O | 0.0343 (−0.0407–0.1094) | 0.4 |

| Blood Type AB vs. O | ND | ND |

| Blood Type B vs. O | 0.0033 (−0.0055–0.0120) | 0.5 |

| HLA Mismatches >=3 | −0.0056 (−0.0200–0.0087) | 0.4 |

The Bonferroni corrected critical p-value for 15 tests is 0.003.

Not determined since there were no early graft failure with this risk factor.

We compared those with PNF with those that had a graft failure between 31 days and a year post-transplant (Table 3) to understand if there were any differences between PNF and other early graft losses. Compared to those graft losses between 31 days and a year post-transplant, recipients with PNF were more likely to have female donors and have fewer HLA A, B, and DR mismatches. These relationships were not replicated in the SRTR control population. There were no other clinically significant differences between recipients with PNF and other recipients with early graft failures.

Table 3.

Characteristics of 38 living donor kidney transplant (KT) facilitated by the National Kidney Registry (NKR) and SRTR controls 2008–2017 with early graft failure by graft loss ≤ 30 days post-transplant.

| NKR | NKR | SRTR Control2 | SRTR Control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 < DCGF ≤ 365 Days | DCGF ≤ 30 Day | 30 < DCGF ≤ 365 Days | DCGF ≤ 30 Day | |

| N | 25 (65.8%) | 13 (34.2%) | 401 (48.5%) | 425 (51.5%) |

| Recipient Characteristics1 | ||||

| Female | 56 | 46.2 | 47 | 41 |

| African-American | 20 | 7.7 | 16.2 | 18 |

| Age (years) | 42.0 (26.0–48.0) | 55.0 (37.0–60.0) | 46 (34–56) | 47 (32–60) |

| Preemptive Transplant | 28 | 23.1 | 40 | 21 |

| Years on Dialysis | 1.7 (0.0–2.7) | 1.5 (0.0–4.1) | 0.4 (0.0–1) | 1.2 (0.3–2) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.9 (22.8–29.8) | 27.8 (25.4–32.6) | 28 (24–33) | 27 (23–32) |

| College Educated | 47.8 | 81.8 | 61 | 58 |

| Public Insurance | 40 | 61.5 | 42 | 50 |

| Diabetes | 20 | 7.7 | 16 | 17 |

| Hypertension | 16 | 15.4 | 15 | 16 |

| HIV | 4.3 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Previous Transplant | 32 | 30.8 | 12 | 14 |

| PRA>80 at Transplant | 8 | 30.8 | 5 | 7 |

| Antibody Depleting Induction | 68 | 58.3 | 69 | 67 |

| Antibody Non-Depleting Induction | 20 | 41.7 | 30 | 27 |

| eGFR Pre-transplant (mL/min/1.7m2) | 7.9 (6.2–13.9) | 7.8 (5.0–15.9) | 10 (6–14) | 8 (6–11) |

| Delayed Graft Function | 20 | 61.5 | 57 | 16 |

| Donor Characteristics | ||||

| Female | 48 | 84.6 | 65 | 66 |

| African-American | 12 | 7.7 | 15 | 15 |

| Age (years) | 47.0 (34.0–53.0) | 42.0 (37.0–57.0) | 42 (33–52) | 45 (35–54) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7 (25.0–28.8) | 25.4 (22.9–28.5) | 27 (24–30) | 26.6 (24–29) |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.7m2) | 98.5 (85.9–107.6) | 94.2 (79.4–100.6) | 100 (88–112) | 97 (86–107) |

| Blood Type A | 32 | 46.2 | 25 | 26 |

| Blood Type A1 | 12 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Blood Type A2 | 0 | 7.7 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Blood Type AB | 16 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Blood Type B | 20 | 23.1 | 10 | 6 |

| Blood Type O | 20 | 23.1 | 62 | 65 |

| 1 Renal Vein | 72 | 92.3 | -3 | - |

| 2 Renal Veins | 8 | 7.7 | - | - |

| 1 Renal Artery | 52 | 76.9 | - | - |

| 2 Renal Arteries | 28 | 23.1 | - | - |

| Transplant Characteristics | ||||

| ABO Incompatible | 8 | 0 | 5 | 3 |

| Zero HLA mismatch | 0 | 7.7 | 7 | 5 |

| 1 HLA mismatch | 4 | 0 | 6 | 5 |

| 2 HLA mismatch | 12 | 7.7 | 20 | 12 |

| 3 HLA mismatch | 8 | 30.8 | 24 | 29 |

| 4 HLA mismatch | 20 | 38.5 | 17 | 17 |

| 5 HLA mismatch | 48 | 7.7 | 19 | 18 |

| 6 HLA mismatch | 8 | 7.7 | 7 | 13 |

| Cold Ischemia Time (hours) | 8.9 (8.0–13.6) | 8.6 (5.8–12.3) | 1 (0.8–2) | 1 (0.6–2) |

Characteristics are presented as percentages for binary variables and median (25 percentile - 75 percentile) for continuous variables.

SRTR controls are non-KPD (NKR or another system) living donor kidney transplant recipients

Information not available in SRTR.

Description of Early Graft Losses

Reasons for PNF were ascertained after chart review (Table 4). Two recipients had undergone intensive desensitization protocols in preparation for receiving their kidney. One of those requiring desensitization was a pediatric recipient (age 7) undergoing retransplant. Both desensitization cases had minimal kidney function, and despite aggressive treatment for antibody-mediated rejection, both experienced early failure.

Table 4.

Cause of Primary Nonfunction in NKR transplants.

| Cause | Incidence (n=13) |

|---|---|

| Standard Anatomy (1–2 renal arteries, 1 renal vein), unclear cause of failure | 6 |

| Possible Donor Surgical Injury | 3 |

| Desensitization Failure/Unsuccessful treatment of AMR | 2 |

| Complex Anatomy (>= 2 veins, >= 3 arteries), postoperative thrombosis | 2 |

In two other failures, complex anatomy appeared to play a role. In one case, two veins were anastomosed with difficulty at the time of transplant, and the patient experienced an irreversible venous thrombosis , despite a return to the operating room and thrombectomy. At another site, the donor kidney had three arteries and a single vein. Following poor initial function, an ultrasound on postoperative day one showed minimal flow to the kidney. The patient returned to the operating room, and two out of the three arteries were reanastomosed. However, the kidney never recovered function.

In five cases with standard anatomy (single renal artery and vein), and one case with two renal arteries, the kidneys were declared as PNF without a clear reason for the failure elucidated.

The remaining three early graft losses (3/2676 or 0.11%) were felt to be directly attributable to a donor procurement injury. The first, in 2015, was a left kidney with a single artery and vein. When the kidney was received by the recipient center, brown colored tissue around the vessels in the hilum appeared to be electrocautery burns. A technical issue was suspected during the procurement leading to arterial spasm and warm ischemia of the organ. The kidney had no postoperative function and loss of diastolic flow on ultrasound. The recipient was brought back to the operating room for two re-explorations, with a transplant nephrectomy performed on the second occasion. Pathology did not show any evidence of rejection, but an inflammatory response most likely secondary to ischemic injury.

The second case, in 2017, was also a left kidney. Preoperatively, the patient was reported to have a single renal artery and vein. During procurement, however, the recovering surgeon discovered a second artery and contacted the recipient center to report this finding. However, on the recipient center back table, three arteries were identified. An upper pole artery was very small, and therefore, sacrificed. After reperfusion, the kidney initially looked well perfused , but within minutes, it appeared globally ischemic with poor doppler signals in the renal parenchyma, but strong signals in the main renal artery and at the anastomoses. Despite multiple efforts by the recipient center to correct the situation, the kidney thrombosed, and a transplant nephrectomy was performed. It was felt that the arteries had been damaged during procurement since the donor surgeon was unaware multiple arteries existed.

The third case was reported to the NKR as a loss due to a procurement injury, but details of the case were not available.

DISCUSSION

Overall, primary non-function and early kidney graft losses in transplants facilitated by the National Kidney Registry are rare. PNF accounted for 0.5% (N=13) of the 2351 KPD transplants during our time of study. Losses to one year remained very low with 0.8% at 3 months, 1.1% at 6 months, and 1.6% at 1 year. In comparison, SRTR data for all recipients undergoing a primary living donor kidney transplant between 1991 and 2014 shows a 1-year unadjusted allograft survival rate is of 97.2%, which is slightly inferior to our reported results (16). A Canadian KPD system reported 5 early graft failures after 240 transplants, with 3 due to primary non-function or technical errors (3/240=1%) (17). In an Austrialian KPD report, there was 1 early graft failure after 100 transplants (18). While concerns regarding another center procuring a live donor kidney for transplant and increased transit times persist, only 3 (0.11%) of the PNF cases were thought to be caused by donor organ injury. These data confirm a very low level of PNF and early graft loss among NKR Centers, and fully support wide participation in KPD especially those with a cadre of highly sensitized patients.

There were no clinically significant differences in donor, recipient, or transplant characteristics between patients with lost grafts compared to those with good function. It is worth noting that there were no differences in cold ischemia or transit time between the two groups. There were no unifying characteristics underlying these early graft losses, including use of right kidneys, complex vascular anatomy, or travel between centers. Due to the infrequent occurrence and lack of common etiology for these early graft losses, we were unable to offer a comprehensive preventative strategy or suggest a change in clinical practice to ameliorate this issue in the future.

One PNF case described previously involved a kidney where the anatomy found intraoperatively differed from the preoperative report. Under NKR guidelines, all centers must obtain either a CT scan or an MRI of all potential donors. In rare instances, whether involved in an exchange or not, a vascular structure will be missed in the initial reading. This emphasizes the importance and duty of the recipient center to review all imaging when initially accepting an organ. In the past, and at the time of this loss, only readings were available online to centers, and actual films had to be requested. However, the NKR has now made vast improvements to the system and all radiology studies are uploaded and available to any reviewing center. With this change, small findings that may have been inadvertently missed by a radiologist and could possibly lead to surgical mishaps in the operating room, will hopefully be picked up by the donor or recipient center involved with the case.

The NKR has developed an organizational algorithm for reviewing and managing issues that come up through the exchange process. The Surgical Board is made up of six surgeons, who either sit on the Medical Board or act as primary surgeons in high volume programs. When a surgical problem is reported, the board requests a description of the problem, photographs, and a timeline of events from both the donor and recipient teams. A conference call is then held with both parties to discuss their experience, concerns, and provide an opportunity for any questions to be raised. This process is also repeated with the donor and recipient centers individually. The Surgical Board then decides whether there is sufficient evidence that the graft loss was due to some issue with the donor nephrectomy. Given the low number of early graft losses demonstrated to be secondary to donor surgical issues, the NKR Medical Board has developed a policy that assures centers that the affected recipients will be offered another compatible kidney following availability. The NKR Medical Board has established an “End-Chain Policy,” that ends chains according to a priority list that includes “patients transplanted within the NKR who experience graft failure within 90 days of the transplant that was a result of an impaired kidney delivered to the recipient center.” This is contingent on immediate reporting of any issue to the NKR, including pictures of the kidney within 8 hours of kidney receipt, and presentation of the case to the NKR Surgical Committee and Medical Board. Simulations have been completed to calculate the ability of the NKR to provide allografts for these early graft losses. Given the low rate attributable to donor surgical injury, the program may reasonably expect to maintain this allocation policy as long as the PNF rates remain low.

A graft loss is tragic for any live donor transplant but can be devastating if the recipient of a compatible pair experiences PNF while participating in KPD. Compatible pairs are those that could have been a direct donation between donor and recipient but have opted to join an exchange program. They do this for a variety of reasons, including an attempt to be matched with a younger donor, one with a more advantageous HLA profile, or to simply in a truly altruistic effort to unlock additional transplants for those without compatible options. Compatible pairs represent a rapidly expanding segment of the NKR. Past studies by Gentry, et al have shown that in a national program, participation of compatible pairs can increase the match rate from 37.4% to 75.4% (8). Since participating centers are encouraged to educate and enroll compatible pairs in the NKR, this group in particular heralded the need for retransplant priority in the event of an early graft loss. If recipients, regardless of compatibility, can be assured they will be prioritized for re-allocation should an initial transplant fail secondary to donor procurement injury, this should settle some fears of participation.

The incidence of primary non-function and early graft loss was low in the paired exchange transplants facilitated by the National Kidney Registry. In addition to the very low rate, recipients are now prioritized for retranplant if the kidney is lost within the first 90 days, when due to technical problems with the donor or other extenuating circumstances deemed attributable to logistics. There have been 5 recipients that have been retransplanted from this policy so far, and all have functioning grafts. This policy assumes that the recipient affected by early graft loss remains an active transplant candidate. This report and new policy enacted by the NKR should provide centers and patients further reassurance and encouragement when participating in a kidney exchange program.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHBLI) grant numbers T32HL007055 (Alvin Thomas) and K24DK101828 (PI: Dorry Segev) Additionally, Dorry Segev is supported by a Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinical Research Mentorship grant and a research grant from the National Kidney Registry.

The National Kidney Registry had a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The other sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication

Study concept and design: Verbesey, Thomas, Flechner, Cooper. Acquisition of data: Verbesey, Thomas, Flechner, Segev. Analysis and interpretation of data: Verbesey, Thomas, Flechner, Cooper. Drafting of the manuscript: Verbesey, Thomas, Waterman, Flechner, Cooper. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Verbesey, Thomas, Ronin, Waterman, Segev, Flechner, Cooper. Obtained funding: Segev. Administrative, technical, and material support: Ronin, Waterman. Study supervision: Cooper.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DGF

delayed graft function

- HRSA

Health Resources and Services Administration

- KPD

kidney paired donation

- KT

kidney transplant(ation)

- LDKT

living donor kidney transplant(ation)

- NKR

National Kidney Registry

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- PNF

primary non-function (loss within 30 days of transplant)

- PRA

panel reactive antibody test

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The analyses described here are the responsibility of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The data reported here have been supplied by the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation (MMRF) as the contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the U.S. Government.

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation. All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Mr. Thomas and Dr. Segev reported institutional grant support from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Segev also report institutional grant support from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and National Kidney Registry. Mr. Ronin is a full-time, paid employee of the National Kidney Registry. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al Ammary F, Bowring MG, Massie AB, Yu S, Waldram MM, Garonzik-Wang J et al. The Changing Landscape of Live Kidney Donation in the United States From 2005 to 2017. Am J Transplant 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bingaman AW, Wright FH Jr., Kapturczak M, Shen L, Vick S, Murphey CL. Single-center kidney paired donation: the Methodist San Antonio experience. Am J Transplant 2012;12(8):2125–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashlagi I, Bingaman A, Burq M, Manshadi V, Gamarnik D, Murphey C et al. Effect of match-run frequencies on the number of transplants and waiting times in kidney exchange. Am J Transplant 2018;18(5):1177–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stepkowski SM, Mierzejewska B, Fumo D, Bekbolsynov D, Khuder S, Baum CE et al. The 6-year clinical outcomes for patients registered in a multiregional United States Kidney Paired Donation program - a retrospective study. Transpl Int 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flechner SM, Thomas AG, Ronin M, Veale JL, Leeser DB, Kapur S et al. The first 9 years of kidney paired donation through the National Kidney Registry: Characteristics of donors and recipients compared with National Live Donor Transplant Registries. Am J Transplant 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waki K, Terasaki PI. Paired kidney donation by shipment of living donor kidneys. Clin Transplant 2007;21(2):186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Treat E, Chow EKH, Peipert JD, Waterman A, Kwan L, Massie AB et al. Shipping living donor kidneys and transplant recipient outcomes. Am J Transplant 2018;18(3):632–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nassiri N, Kwan L, Bolagani A, Thomas AG, Sinacore J, Ronin M et al. The “oldest and coldest” shipped living donor kidneys transplanted through kidney paired donation. Am J Transplant 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holscher CM, Jackson K, Thomas AG, Haugen CE, DiBrito SR, Covarrubias K et al. Temporal changes in the composition of a large multicenter kidney exchange clearinghouse: Do the hard-to-match accumulate? Am J Transplant 2018;18(11):2791–2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holscher CM, Jackson K, Chow EKH, Thomas AG, Haugen CE, DiBrito SR et al. Kidney exchange match rates in a large multicenter clearinghouse. Am J Transplant 2018;18(6):1510–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flechner SM, Thomas AG, Ronin M, Veale JL, Leeser DB, Kapur S et al. The first 9 years of kidney paired donation through the National Kidney Registry: Characteristics of donors and recipients compared with National Live Donor Transplant Registries. Am J Transplant 2018;18(11):2730–2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veale J, Hil G. The National Kidney Registry: transplant chains--beyond paired kidney donation. Clin Transpl 2009:253–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veale J, Hil G. National Kidney Registry: 213 transplants in three years. Clin Transpl 2010:333–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veale J, Hil G. The National Kidney Registry: 175 transplants in one year. Clin Transpl 2011:255–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massie AB, Kuricka LM, Segev DL. Big Data in Organ Transplantation: Registries and Administrative Claims. American Journal of Transplantation 2014;14(8):1723–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang JH, Skeans MA, Israni AK. Current Status of Kidney Transplant Outcomes: Dying to Survive. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2016;23(5):281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cole EH, Nickerson P, Campbell P, Yetzer K, Lahaie N, Zaltzman J et al. The Canadian kidney paired donation program: a national program to increase living donor transplantation. Transplantation 2015;99(5):985–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen R, Pleass H, Clayton PA, Woodroffe C, Ferrari P. Outcomes of kidney paired donation transplants in relation to shipping and cold ischaemia time. Transpl Int 2016;29(4):425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.