Abstract

Background

Changes in resting state functional connectivity (rs-fc) occur in Alzheimer disease (AD), but few longitudinal rs-fc studies have been performed. Most studies focus on single networks and not a global measure of rs-fc. Although the amyloid tau neurodegeneration (AT(N)) framework is increasingly utilized by the AD community, few studies investigated when global rs-fc signature changes occur within this model.

Objectives

1) Identify a global rs-fc signature that differentiates cognitively normal (CN) individuals from symptomatic Alzheimer Disease (AD). 2) Assess when longitudinal changes in rs-fc occur relative to conversion to symptomatic AD. 3) Compare rs-fc with amyloid, tau and neurodegeneration biomarkers.

Methods

A global rs-fc signature composed of intra-network connections was longitudinally evaluated in a cohort of cognitively normal participants at baseline (n = 335). Biomarkers, including cerebrospinal fluid (Aβ42 and tau), structural magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography were obtained.

Results

Global rs-fc signature distinguished CN individuals from individuals who developed symptomatic AD. Changes occurred nearly four years before conversion to symptomatic AD. The global rs-fc signature most strongly correlated with markers of neurodegeneration.

Conclusions

The global rs-fc signature changes near symptomatic onset and is likely a neurodegenerative biomarker. Rs-fc changes could serve as a biomarker for evaluating potential therapies for symptomatic conversion to AD.

Keywords: Neuroimaging, Observational Studies, Biomarkers, Alzheimer Disease

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer Disease (AD) is a slowly progressive process with pathological changes seen as early as twenty years before symptomatic onset (Jack et al., 2010).The amyloid-tau-neurodegeneration (AT(N)) framework (Jack et al., 2018) is a potential model for evaluating biomarker changes in AD throughout the course of the disease. It is hypothesized that individuals first develop amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques followed by neurofibrillary tau tangles (NFT) then neurodegeneration and finally symptomatic cognitive impairment. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) (Morris, 2018) rates the severity of symptoms with cognitively normal individuals classified as CDR 0 and individuals with symptomatic AD having a CDR ≥ 0.5. Individuals with symptomatic AD (McKhann et al., 2011) have a higher frequency of brain pathology including the presence of Aβ plaques and NFT(Morris and Price, 2001).

Changes in Aβ and NFT could lead to neuronal changes that may associate with cognitive impairment. Resting state functional connectivity (rs-fc) MRI assesses brain function by measuring the temporal correlation of spontaneous fluctuations in the blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal between regions (Badhwar et al., 2017). Correlated regions have been reproducibly classified into resting-state networks (RSNs) that recapitulate the topographies seen for task-related functional responses (Power et al., 2011). Rs-fc has previously been shown to differ between cognitively normal individuals and symptomatic AD participants (Lustig et al., 2003; Greicius et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2008; Qi et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2012), but has been limitedly assessed in a longitudinal context (Chiesa et al., 2018; Schultz et al., 2018). Of the available longitudinal rs-fc studies, many focused on particular RSNs or regions of interest based on a priori assumptions with the default mode network (DMN) and memory (MEM) networks most often interrogated. Changes in the DMN occur in symptomatic AD (Greicius et al., 2004; Buckner et al., 2005; Chhatwal et al., 2013; Chiesa et al., 2018; Staffaroni et al., 2018). Within this RSN a biphasic response has been observed with some portions of the DMN display elevated functional activity while other regions show decreases in activity (Qi et al., 2010). However, conflicting results have been observed as to when rs-fc changes in the DMN occur in relation to other biomarkers. Some studies observe correlations with deposition of amyloid (Mormino et al., 2011; Schultz et al., 2017) while others with tau (Wang et al., 2013).

Multiple RSNs may be affected. A metric of brain health based on a global rs-fc signature should be considered. This metric would be similar to what is derived for cortical amyloid accumulation, cortical tau accumulation (Mintun et al., 2006), and cortical thickness (Dickerson et al., 2009). To date, a global rs-fc signature has not been formally included within the AT(N) framework. Here, longitudinal changes in rs-fc were evaluated within the AT(N) context by: 1) identifying a global rs-fc signature that distinguishes symptomatic AD from cognitively normal individuals; 2) assessing when changes in this global rs-fc signature occur in individuals who converted to symptomatic AD (CDR > 0) compared to those who remained cognitively normal (CDR 0); 3) evaluating the relationship between this global rs-fc signature and other AD biomarkers typically included in the AT(N) criteria.

METHODS

Participants

Three hundred thirty-five participants enrolled in longitudinal studies at the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) at Washington University in St Louis (WUSTL) were evaluated (Table 1). Methods for recruitment have previously been described (Morris et al., 2019). All participants were cognitively normal (CDR 0) at the time of enrollment. Within this group we compared individuals who remained cognitive normal (CDR 0) and amyloid negative throughout the study period (as measured by previously published cutoffs for amyloid PET using Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) (Su et al., 2013) or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ42 (Schindler et al., 2018)) (n=290) to a group that converted to CDR > 0 and, by clinical evaluation, had a diagnosis of symptomatic AD (n=45). Participants were evaluated for a mean of 6.33 ± 5.57 years and were included in analyses if they had at least two clinical visits for CDR assessment, one or more structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and at least one rs-fc scan. All clinical visits for each participant were included. This study was approved by the WUSTL Institutional Review Board and each participant provided signed informed consent.

Table 1.

Demographics of cognitively normal participants at baseline (n=335) who either remained cognitively normal and who had no biomarker evidence of amyloid (non-converter) throughout or individuals who became cognitively impaired (converter).

| Non-Converter | Converter | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 290 | 45 | |

| Age (years) (mean (SD)) | 67.3 (9.1) | 77.6 (6.8) | <0.001 |

| Education (years) (mean (SD)) | 16.1 (2.5) | 15.9 (3.3) | 0.622 |

| Gender (% female) | 183 (63.1) | 25 (55.6) | 0.420 |

| APOE ε4+ (%) | 79 (29.2) | 15 (33.3) | 0.504 |

| Race (%) | 0.854 | ||

| Asian | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| African-American | 26 (9.0) | 4 (8.9) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 260 (90.3) | 41 (91.1) |

APOE= Apolipoprotein E SD= standard deviation

Data Availability Statement

Data associated with the Knight ADRC is available on request, via www.knightadrc.wustl.edu/Research/ResourceRequest.htm. Details regarding the number of participants who had each biomarker modality and the number of repeated data points is provided within Supplemental Tables 1–4.

CDR status

All individuals participating in Knight ADRC studies undergo regular clinical assessments. The CDR evaluates the degree of cognitive impairment (Morris and Price, 2001; McKhann et al., 2011). Only participants with CDR > 0 and an accompanying clinical diagnosis of dementia due to AD were considered to have symptomatic AD for this analysis (McKhann et al., 2011). Participants with CDR > 0 but a clinical diagnosis suggestive of other etiologies (e.g. fronto-temporal dementia or bereavement due to the recent death of a spouse) were not included. Participants who were initially CDR 0 and later transitioned to CDR > 0 due to symptomatic AD were referred to as “converters”. CDR 0 individuals who remained cognitively normal and were amyloid negative throughout the study were referred to as “non-converters”. CDR 0 individuals who became amyloid positive during the study were not included as it was more likely that these individuals would convert to symptomatic AD at some point, even if this conversion did not occur during the duration of the study.

APOE status

DNA samples were collected at enrollment and genotyped using either an Illumina 610 or Omniexpress chip. A complete description of genotyping methods has been previously published (Cruchaga et al., 2013). In order to include the effects of Apolipoprotein ε4 (APOE ε4 genotype) in this analysis, APOE was converted from a genotype to a binary variable, indicating if an individual was either “APOE ε4+”, that is, that an individual possessed at least one copy of the APOE ε4 allele, or “APOE ε4-”.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) acquisition

CSF was collected as previously described (Fagan et al., 2006). Briefly, participants underwent lumbar puncture at 8 AM following overnight fasting. Approximately 25 mL of CSF was collected in a 50 ml polypropylene tube via gravity drip using an atraumatic Sprotte 22-gauge spinal needle. The sample was gently mixed to disrupt potential gradient effects and then centrifuged at low speed to pellet any debris. The CSF was aliquoted into polypropylene tubes and aliquots were stored at −80°C until the time of assay. CSF Aβ42, total tau (tTau), and tau phosphorylated at 181 (pTau) were measured with corresponding Elecsys immunoassays on the Roche cobas e601 analyzer (Schindler et al., 2018). For each analyte, a single lot of Elecsys reagents was used.

Amyloid and tau positron emission tomography (PET) acquisition and processing

PET images were acquired using methodology previously described (Mintun et al., 2006; Su et al., 2015; Day et al., 2017). Additional details regarding image acquisition and processing are also available in the Supplement. PET data were processed using a PET Unified Pipeline (github.com/ysu001/PUP). A region of interest (ROI) segmentation approach within FreeSurfer 5.3 was employed. For each region, a tissue mask was generated based on segmentation. Partial volume correction was performed (Su et al., 2015). Regional target-to-reference intensity ratio, also known as the standard uptake ratio (SUVR), was evaluated for each region using the cerebral cortex as the reference region. The partial volume corrected SUVR derived from cortical regions was used as a summary value for each PET imaging modality.

Amyloid PET imaging was performed with [11C] Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) (Mintun et al., 2006). Dynamic scans were obtained after injecting participants with 12 – 15 mCI of PiB. The time window for quantification was 30 – 60 minutes post-injection.

Tau PET imaging was performed with [18F]-Flortaucipir (AV1451) (Day et al., 2017). Participants received a single 6.5–10 mCI bolus of AV1451 intravenously infused over 20 seconds. Imaging and processing for tau PET imaging was identical to amyloid PET imaging, with the exception of the time window used for quantification (80 – 100 minutes).

MRI structural and rs-fc acquisition and processing

MRI images were collected on a 3T Siemens Trio scanner (Erlangen, Germany). Additional details regarding image acquisition and processing are also available in the Supplement. T1-weighted scans were segmented using FreeSurfer 5.3 (Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Charlestown, Massachusetts, USA). For this analysis, the hippocampal volume, as segmented by FreeSurfer, and AD cortical signature regions (Wang et al., 2015) were considered as biomarkers of neurodegeneration. To compute the AD cortical signature region, each relevant brain region (entorhinal cortex, fusiform gyrus, inferior, middle and superior temporal gyri, superior and inferior parietal lobules, posterior cingulate gyrus, and precuneus) was individually normalized and then averaged to obtain a single Z score for the AD signature volume. The hippocampal volume Z score was obtained similarly.

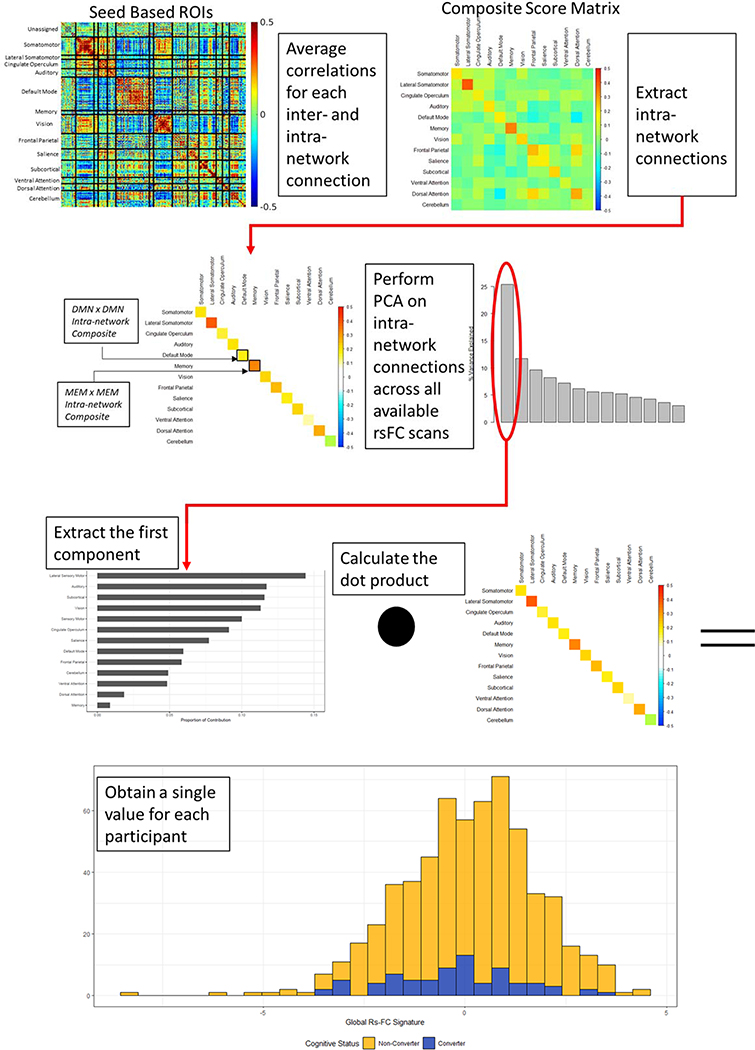

Methods of rs-fc acquisition have previously been described (Greicius et al., 2004; Buckner et al., 2005; Power et al., 2011). Detailed information is available in the supplement. Post-processing of rs-fc data is illustrated in Figure 1. 298 seed-based functional regions of interest (ROI) were identified (Power et al., 2011); mean time series for each ROI were calculated; and then pairwise correlations between each ROI were calculated. These 298 ROIs were sorted into 13 previously defined networks (Power et al., 2011). In order to obtain a global rs-fc signature value, values from 13 intra-network connections (Power et al., 2011) were extracted from the 13 × 13 composite score matrix. A singular value decomposition was performed on the 13 scaled and centered RSN composite scores across all available rs-fc scans in this cohort. The eigenvector corresponding to the first principal component was multiplied by each individual’s intra-network connections (that is, the diagonal of each individual’s composite resting state matrix) to generate a single summary value describing an individual’s global rs-fc signature (Smith et al., 2018). This manuscript focused on intra-network connections as these connections change with healthy aging (Goh, 2011) and conversion to symptomatic AD (Brier et al., 2012). Overall, a higher global rs-fc signature value indicates stronger within network connection. Similar to the “AD Cortical Signature” or summary values of amyloid PET accumulation and tau PET accumulation, the “AD global rs-fc signature” creates a summary metric that succinctly describes functional connectivity changes due to AD.

Figure 1.

A series of post-processing steps were performed on rs-fc data in order to reduce dimensionality and generate a single summary value. 298 seed-based functional regions-of-interest (ROI) were identified and Pearson correlations between each were calculated and Z transformed for normality. These ROIs were organized into thirteen resting state networks (RSNs), with ROIs of unknown function classified as “unassigned”. Correlations within each of the thirteen RSNs were averaged to obtain a 13 × 13 matrix for each individual. We then performed PCA on the intra-network connections for each individual, that is, the diagonal of each individual’s rs-fc matrix. We calculated the dot product of the eigenvector corresponding to the first principal component and the intra-network connections on an individual-by-individual basis to obtain a single summary value referred to as “AD global rs-fc signature”. Certain networks have been previously shown to be affected by AD. Post hoc analyses using the DMN x DMN intra-network composite and the MEM x MEM intra-network composite were therefore performed. These intra-network composites are labeled for clarity here.

Years to onset (YO)

For participants who converted to CDR > 0 (converters), their time to symptomatic onset was defined relative to the day of their first clinical rating of CDR > 0 using previously described methods (Morris, 2018). For participants who remained CDR 0 (non-converters), a simulated date of onset was assigned by randomly selecting a clinical visit date that was not their first clinical visit date (Roe et al., 2018). This clinical visit date was defined as the participant’s simulated date of onset. Years before or after date of onset were calculated by subtracting the date of the data collection from the date of onset.

Statistical analysis

Group differences between converters and non-converters were compared using t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. A linear mixed effect regression, assuming participant visits at random, was applied to evaluate longitudinal differences in the global rs-fc signature over time for converters compared to non-converters. This analysis included APOE ε4 status, education, sex, time to assigned symptomatic onset, and the interaction of APOE ε4 and time to onset as fixed effects. Age was not included as a fixed effect due to its collinearity with time to assigned symptomatic onset. Repeated measures for individuals were taken into account with inclusion of a unique participant identifier as a random effect.

To study relationships between the global rs-fc signature and other AD biomarkers, a linear mixed effect regression was performed for all biomarkers that had repeated measures (amyloid PET, CSF, and MRI volumetrics) to correct these values for possible differences in age, sex, education, and APOE ε4 status. A repeated measures correlation coefficient was calculated between each corrected response variable of interest (measures of amyloid, tau, and neurodegeneration) and the global rs-fc signature value using a bootstrap approach (5000 iterations) (Efron, 1979). For tau PET imaging, repeated measures were unavailable. Instead, Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated for tau PET scans and the nearest available rs-fc scan. All analyses were conducted using R (R Core Development Team, 2013). Correlation analysis relied on the package rmcorr (Bakdash and Marusich, 2017). Linear mixed effect modeling used lme4 (Bates et al., 2015). Analysis code is publicly available at github.com/jwisch.

RESULTS

Participants who converted to symptomatic AD were older than non-converting participants (p < 0.001); however, no other differences in demographic variables were observed (Table 1). The global rs-fc signature is a weighted combination of 13 intra-network connections (Figure 1). The first principal component associated with the singular value decomposition of the correlation matrix had a variance of 3.30, representing 25% of the total variance explained by the 13 components. Networks that made the largest contribution to this first principal component were primary sensory regions. The rs-fc signature represents a single global measure, and more nuanced changes within individual networks cannot be interpreted from this method. The global rs-fc signature changed over time for all participants (p < 0.001) (Table 2), aligning with previous work suggesting that dedifferentiation of functional networks occurs with aging [34]. Converters exhibited a more rapid decline in the global rs-fc signature than non-converters (p = 0.004). The global rs-fc signature was significantly different between converters and non-converters at 3.90 years (Standard Error Range: 2.72 – 4.15 years) before symptomatic conversion (Figure 2), placing this measure relatively late in the disease progression cascade.

Table 2.

Linear mixed effect model that predicts the global resting state functional connectivity (rs-fc) signature

| rs-fc Signature ∼ Converter+Years to Onset+APOE4+Converter:Years to Onset+Gender+Education+APOE4:Years to Onset+(1|ID) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | CI | p | |

| Fixed Effects | |||

| (Intercept) | −1.069 | (−2.429, 0.292) | 0.124 |

| Non-Converter | 0.352 | (0.079, 0.626) | 3.70e-03** |

| Years to Onset | −0.150 | (−0.224, −0.087) | 6.21e-05*** |

| APOE ε4+ | −0.077 | (−0.278, 0.125) | 0.469 |

| Gender | −0.076 | (−0.444, 0.292) | 0.683 |

| Education | 0.054 | (−0.014, 0.122) | 0.120 |

| Non-Converter × Years to Onset | 0.090 | (0.029, 0.151) | 3.66e-03** |

| APOE ε4+ × Years to Onset | 0.017 | (−0.028, 0.063) | 0.4545 |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

CI= confidence interval

Figure 2.

Changes in intra-network rs-fc signature over time for cognitively normal individuals (clinical dementia rating (CDR) 0) who either converted to symptomatic AD (CDR >0) (converters) or who remained cognitively normal (CDR 0) (non-converter). Significant differences between the two groups were seen 3.9 years before symptomatic conversion.

Because the PCA-based approach identified a global rs-fc signature that could vary across individuals, we repeated our analyses concentrating on the DMN x DMN intra-network composite (See Figure 1) and the MEM x MEM intra-network composite (See Figure 1) as these two networks are hypothesized to be affected during the early stages of symptomatic AD conversion. We also generated a reverse weighted global signature (Supplement, Figure 6) since the order of network importance in the global rs-fc signature emphasized sensory networks rather than other networks such as the DAN, VAN, DMN, and MEM networks. The DMN (Supplement, Figure 2) and MEM (Supplement, Figure 4) intra-network composites successfully distinguished between converters and non-converters, but only 6 months or 2.4 years prior to conversion, respectively. The reverse weighted composite (Supplement, Figure 7) performed nearly as well as the original global rs-fc signature, separating 3.70 (95% CI: 2.79, 5.65) years prior to symptomatic conversion.

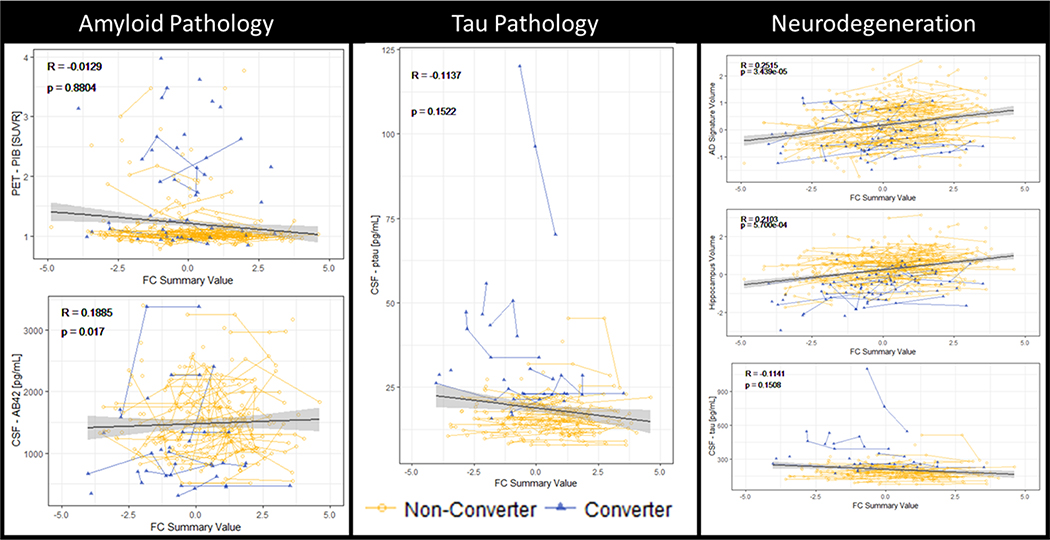

After identifying that the global rs-fc signature changed several years before conversion to symptomatic AD, we compared this measure with respect to other AD biomarkers included in the AT(N) framework. The global rs-fc signature was tested for correlation with markers of amyloid, tau, and neurodegeneration (Figure 3). With regards to amyloid measures, CSF Aβ42 was positively associated with a greater global rs-fc signature (R = 0.189, p = 0.017); however, amyloid accumulation as measured by PiB-PET was not significantly correlated with the global rs-fc signature (R = −0.013, p = 0.880). There was no correlation between tau pathology and global rs-fc signature (CSF pTau: R = −0.114, p = 0.152). Decreases in the global rs-fc signature were associated with smaller volumes in the hippocampus (R = 0.210, p < 0.001) and the AD volumetric signature (R = 0.252, p < 0.001) (Figure 3). There was no significant relationship between Tau-PET and global rs-fc signature (R = −0.114, p = 0.151) (Supplement, Figure 1).

Figure 3.

Correlations between intra-network rs-fc signature and biomarkers of Alzheimer disease (AD) In particular, intra-network rs-fc was correlated with one of the amyloid (A) measures (cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) AΒ42, but not PET-PIB) and the volumetric measures of neurodegeneration normalized hippocampal volume, and AD cortical signature), but not CSF measures of tau (T) or neurodegeneration (N). The intra-network rs-fc correlated strongest with volumetric markers of neurodegeneration.

We repeated this analysis using the DMN intra-network correlation composite (Supplement, Figure 3), the MEM intra-network correlation composite (Supplement, Figure 5), and the reverse weighted composite (Supplement, Figure 8). The DMN x DMN composite did not correlate with any of the AT(N) measures. The MEM x MEM composite correlated with markers of tau (CSF pTau R = −0.190, p = 0.016) and neurodegeneration [cortical signature (R = 0.248, p < 0.0001) and CSF tTau (R = −0.156, p = 0.049)], but not amyloid [CSF Aβ42; (R = 0.08, p = 0.312); amyloid PET (R = −0.124, p = 0.147)]. The reverse weighted composite recapitulated results observed for the original global rs-fc signature.

DISCUSSION

Within our cohort of cognitively normal individuals at baseline, 13% (n = 45) of the participants converted to symptomatic AD. Primary sensory areas were heavily involved in the composition of the global rs-fc signature. In our longitudinal analysis, we observed that the global rs-fc signature changed over time for all participants. A small decline in the global rs-fc signature occurred with healthy aging and a significantly greater decline was seen in individuals who converted to symptomatic AD. Separation between converters and non-converters could be observed nearly four years prior to symptomatic onset of AD. The rs-fc signature correlated with some AT(N) biomarkers, including CSF Aβ42 and most strongly with neurodegenerative measures including hippocampal and AD signature volumes. This global rs-fc value represents a potential single descriptor of the state of an individual’s resting state characteristic, comparable to summary values of amyloid, tau and neurodegeneration that have previously been described (Jack et al., 2018).

The composition of the global rs-fc signature was somewhat unexpected. We would have anticipated that networks like the DMN and MEM would have been heavily involved instead of primary sensory motor networks (SMN). This could reflect current seed based methodology, which has relatively few seeds within areas that are most often affected by AD such as the entorhinal and perirhinal regions. However, a recent fMRI study modeled the cerebral cortex as a large-scale dynamic circuit and found a hierarchical control network model controlled by the DMN at one end, and the SMN at the other end (Wang et al., 2019). The SMN may exercise control over sensory input networks including the visual and auditory networks (Wang et al., 2019), while the DMN associates with internal processing. It may be that the observed global rs-fc signature reflects changes in the SM rather than the DMN portion of this rs-fc hierarchy. Previous studies have documented motor dysfunction in as a risk factor for the development of symptomatic AD (Aggarwal et al., 2006), as well as suggested that preclinical AD is associated with falls in older adults (Stark et al., 2013). Similar associations have also been observed between cognition and both auditory (Lin, 2011) and visual (Rogers and Langa, 2010) processing.

When we considered other possible signatures including individual RSNs (DMN x DMN and MEM x MEM) or global metrics (reverse-weighted global rs-fc signature) that more closely aligned with our a priori expectations, we did not observe an improvement in our ability to separate converters and non-converters. Prior work has shown that parts of the DMN become hyper-connected while other parts become hypo-connected during the progression to symptomatic AD (Qi et al., 2010; Mormino et al., 2011; Schultz et al., 2018), and we expect that this heterogeneity obscures changes in an overall correlation composite. This effect could also extend to the MEM x MEM composite. It was notable that the reverse weighted signature performed nearly as well (3.7 years vs. 3.9 years, p > 0.05) as the original global rs-fc signature. It appears that a global rs-fc signature, rather than rs-fc from an individual ROI or RSN, may be better for identifying changes associated with conversion to symptomatic AD.

We compared the global rs-fc signature to proposed AT(N) biomarkers (Jack et al., 2018). We performed comparisons within a longitudinal context, with the exception of tau PET. Only single visits were available for tau PET as this is a recently developed biomarker. Disruption of the global rs-fc signature was preferentially associated with CSF Aβ42 and hippocampal atrophy, biomarkers that characterize pathological changes occurring during the early and late stages of AD, respectively. Changes in global rs-fc signature during the very early period may reflect hyper connectivity as increases in endogenous neuronal activity (as measured by stronger intra-network connectivity) regulates regional concentration Aβ and can lead to greater Aβ deposition. We also observed the strongest correlations between global rs-fc signature and neurodegenerative measures (Jack et al., 2010) as a sufficient number of participants converted to symptomatic AD. A decline in global rs-fc signature occurred approximately 4 years prior to AD and was significantly correlated with hippocampal atrophy.

When we repeated our analyses comparing other potential rs-fc signatures with AT(N) biomarkers we observed varying results. A RSN composite of the DMN x DMN was not correlated with any of the AT(N) biomarkers while the MEM x MEM composite correlated only with neurodegeneration measures. The reverse weighted global rs-fc signature recapitulated our results observed for the original global rs-fc signature. Previous rs-fc studies have shown correlations between the DMN and amyloid (Mormino et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013; Schultz et al., 2017); however, these studies compared either subcomponents of the DMN with global amyloid deposition (Mormino et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013) or compared entire network connections with ROI-specific amyloid accumulation (Schultz et al., 2017). Similarly, work proposing a connection between rs-fc and tau primarily focused on specific ROI subcomponents (Petersen et al., 2010).

Our study has several limitations. Few participants were followed until autopsy, instead we used a cohort of convenience. Participants were followed for up to ten years before symptomatic onset, but we may not be able to capture some of the earliest changes associated with amyloid. In order to fully capture changes in this relationship participants may need to be followed more than fifteen years prior to symptom onset. Further, converters were significantly older than non-converters, and we were unable to include this as a covariate in the model due to collinearity with the year of onset variable. This age-related difference may contribute to the difference in signal from converters as compared to non-converters. Despite these limitations with respect to cohort composition, the incidence rate of AD in this cohort was similar to the incidence rate of 16% mild cognitive impairment (MCI) observed in community dwelling individuals reported by Mayo Clinic (Petersen et al., 2010), but somewhat lower than the 25% MCI and AD incidence rate that has been reported by Harvard Aging Brain Study (HABS) (Johnson et al., 2016).

An additional limitation of this work was our inability to compare the global rs-fc signature with longitudinal tau PET data. We did not see a correlation between the global rs-fc signature and cross sectional tau PET (Supplement, Figure 1), but future efforts to analyze rs-fc in light of longitudinal PET-tau data should be performed. Finally this work was performed in a well characterized cohort of individuals that are followed by the Knight ADRC cohort. Future studies should apply the global rs-fc signature to other cohorts in order to validate its temporal relationship between converter/non-converter and compare it to other AT(N) biomarkers. It should also be noted that BOLD is neurovascular in origin and could be confounded by non-AD specific comorbidities. Despite these limitations, our results are strengthened by their emphasis on longitudinal data, which is difficult to obtain and frequently absent from the literature (Lawrence et al., 2017). We made methodological choices to maximize our power (Bakdash and Marusich, 2017), and compared the global rs-fc signature to a large variety of biomarkers.

CONCLUSIONS

Global rs-fc signature changes are observable nearly four years prior to symptomatic conversion to AD and strongly correlated with neurodegeneration markers. If successfully replicated in other studies the global rs-fc signature could serve as a clinical trial biomarker of brain health especially during conversion to symptomatic AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH) grants R01NR012907 (BA), R01NR012657 (BA), R01NR014449 (BA), R01MH118031 (BA), R01AG052550 (BA), R01AG057680 (BA), P01AG00391 (JCM), P01AG026276 (JCM), and P01AG005681 (JCM). This work was also supported by the generous support of the Barnes-Jewish Hospital; the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences Foundation (UL1 TR000448); the Hope Center for Neurological Disorders; the Paula and Rodger O. Riney Fund; the Daniel J Brennan MD Fund; and Fred Simmons and Olga Mohan Fund.

Disclosures

Julie K. Wisch reports no disclosures

Catherine M. Roe reports no disclosures

Ganesh M. Babulal reports no disclosures

Suzanne E. Schindler reports no disclosures

Anne M. Fagan has received research funding from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health, Biogen, Centene, Fujirebio and Roche Diagnostics. She is a member of the scientific advisory boards for Roche Diagnostics, Genentech and AbbVie and also consults for Araclon/Grifols, Diadem, and DiamiR. There are no conflicts.

Tammie L. Benzinger has consulted on clinical trials with Biogen, Roche, Jaansen, and Eli Lilly. She receives research support from Eli Lilly and Avid Radiopharmaceuticals. Avid Radiopharmaceuticals provided the AV-1451 used in this study.

John C. Morris reports no disclosures

Beau M. Ances reports no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- [1].Jack CR Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Aisen PS, Weiner MW, Petersen RC, et al. (2010) Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. The Lancet Neurology. 9(1), 119–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, … & Liu E NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018; 14(4): 535–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Morris JC Clinical dementia rating: a reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int psychogeriatr. 1997; 9(S1): 173–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011; 7(3), 263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Morris JC, & Price JL Pathologic correlates of nondemented aging, mild cognitive impairment, and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2001; 17(2): 101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Badhwar A, Tam A, Dansereau C, Orban P, Hoffstaedter F, & Bellec P Resting-state network dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2017; 8: 73–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Power JD, Cohen AL, Nelson SM, et al. , Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron. 2011; 72(4): 665–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Johnson KA, Fox NC, Sperling RA, & Klunk WE, Johnson Keith A., et al. Brain imaging in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012, 24: a006213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chen G, Ward BD, Xie C, Li W, Wu Z, Jones JL, Franczak M, et al. Classification of Alzheimer disease, mild cognitive impairment, and normal cognitive status with large-scale network analysis based on resting-state functional MR imaging. Radiol. 2011; 259(1): 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lustig C, Snyder AZ, Bhakta M, O’Brien KC, McAvoy M, Raichle ME, Morris JC, et al. Functional deactivations: change with age and dementia of the Alzheimer type. PNAS. 2003; 100(24): 14504–14509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Liu Y, Wang K, Chunshui YU, He Y, Zhou Y, Liang M, & Jiang T Regional homogeneity, functional connectivity and imaging markers of Alzheimer’s disease: a review of resting-state fMRI studies. Neuropsychol. 2008; 46(6): 1648–1656. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0028393208000638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Greicius MD, Srivastava G, Reiss AL, & Menon V Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer’s disease from healthy aging: evidence from functional MRI. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004; 101(13), 4637–4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Qi Z, Wu X, Wang Z, Zhang N, Dong H, Yao L, & Li K (2010). Impairment and compensation coexist in amnestic MCI default mode network. Neuroimage, 50(1), 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schultz AP, Chhatwal JP, Hedden T, Buckley RF, Johnson KA, & Sperling RA Longitudinal Change of Functional Connectivity in Preclinical AD: Results from the Harvard Aging Brain Study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2018; 14(7), P41–P42. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chiesa PA, Cavedo E, Potier MC, Lista S, Dubois B, de Schotten MT, & Hampel H APOE-Dependent Longitudinal Changes in Default Mode Network Functional Connectivity in Subjective Memory Complainers. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2018; 14(7), P474. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Shannon BJ, LaRossa G, Sachs R, Fotenos AF, Sheline YI, et al. Molecular, structural, and functional characterization of Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for a relationship between default activity, amyloid, and memory. J. Neuroscience. 2005; 25(34), 7709–7717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Staffaroni AM, Brown JA, Casaletto KB, Elahi FM, Deng J, Neuhaus J, Cobigo Y, et al. The longitudinal trajectory of default mode network connectivity in healthy older adults varies as a function of age and is associated with changes in episodic memory and processing speed. J. Neuroscience. 2018; 38(11), 2809–2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chhatwal JP, Schultz AP, Johnson K, Benzinger TL, Jack C, Ances BM, Sullivan CA, et al. Impaired default network functional connectivity in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2013; 81(8), 736–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Schultz AP, Chhatwal JP, Hedden T, Mormino EC, Hanseeuw BJ, Sepulcre J, Huijbers W, et al. Phases of hyperconnectivity and hypoconnectivity in the default mode and salience networks track with amyloid and tau in clinically normal individuals. Journal of Neuroscience. 2017; 37(16), 4323–4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mormino EC, Smiljic A, Hayenga AO, Onami H, S., Greicius MD, Rabinovici GD, et al. Relationships between beta-amyloid and functional connectivity in different components of the default mode network in aging. Cerebral cortex. 2011; 21(10), 2399–2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang L, Brier MR, Snyder AZ, Thomas JB, Fagan AM, Xiong C, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42, phosphorylated Tau181, and resting-state functional connectivity. JAMA neurology. 2013; 70(10), 1242–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, Dence CS, Lee SY, Mach RH, et al. [11C] PIB in a nondemented population Potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurol. 2006; 67(3): 446–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dickerson BC, Feczko E, Augustinack JC, Pacheco J, Morris JC, Fischl B, & Buckner RL Differential effects of aging and Alzheimer’s disease on medial temporal lobe cortical thickness and surface area. Neurobiology of aging. 2009; 30(3), 432–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Morris JC, Schindler SE, McCue LM, Moulder KL, Benzinger TL, Cruchaga C, et al. Assessment of racial disparities in biomarkers for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Su Y, D’Angelo GM, Vlassenko AG, Zhou G, Snyder AZ, Marcus DS, et al. Quantitative analysis of PiB-PET with freesurfer ROIs. PloS one. 2013; 8(11): e73377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Schindler SE, Gray JD, Gordon BA, Xiong C, Batrla-Utermann R, Quan M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers measured by Elecsys assays compared to amyloid imaging. Alzheimers Dement. 2018; 14(11), 1460–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cruchaga C, Kauwe JS, Harari O, Jin SC, Cai Y, Karch CM, et al. GWAS of cerebrospinal fluid tau levels identifies risk variants for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2013; 78(2): 256–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, et al. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 in humans. Ann Neurol. 2006; 59: 512–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Schindler SE, Gray JD, Gordon BA, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers measured by Elecsys assays compared to amyloid imaging. Alzheimers Dement. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Su Y, Blazey TM, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME, Marcus DS, Ances BM, et al. Partial volume correction in quantitative amyloid imaging. Neuroimage. 2015; 107: 55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Day GS, Gordon BA, Jackson K, Christensen JJ, Rosana MP, Su Y, et al. Tau-PET Binding Distinguishes Patients with Early-stage Posterior Cortical Atrophy From Amnestic Alzheimer Disease Dementia. Alzheimers DisAssoc Disord. 2017; 31(2): 87–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wang L, Benzinger TL, Hassenstab J, Blazey T, Owen C, Liu J, et al. Spatially distinct atrophy is linked to β-amyloid and tau in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurol. 2015; 84(12): 1254–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Smith RX, Tanenbaum A, Strain JF, Gordon BA, Fagan AM, Hassenstab J, et al. Resting-State Functional Connectivity is Associated with Pathological Biomarkers in Autosomal Dominant Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018; 14(7): P1480. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Goh JO Functional dedifferentiation and altered connectivity in older adults: neural accounts of cognitive aging. Aging Dis. 2011; 2(1): 30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Brier MR, Thomas JB, Snyder AZ, Benzinger TL, Zhang D, Raichle ME, et al. , Loss of Intranetwork and Internetwork Resting State Functional Connections with Alzheimer’s Disease Progression. J Neurosci. 2012; 32(26): 8890–8899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Roe CM, Ances BM, Head D, Babulal GM, Stout SH, Grant EA, et al. Incident cognitive impairment: longitudinal changes in molecular, structural and cognitive biomarkers. Brain. 2018; 141(11): 3233–3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Efron B Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife In Breakthroughs in Statistics (pp. 569–593). Springer, New York, NY; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- [38].R Core team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Bakdash JZ, & Marusich LR Repeated measures correlation. FrontPsychol. 2017; 8: 456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, & Walker S Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015; 76(1). doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wang P, Kong R, Kong X, Liégeois R, Orban C, Deco G, et al. Inversion of a large-scale circuit model reveals a cortical hierarchy in the dynamic resting human brain. Science advances. 2019; 5(1), eaat7854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Aggarwal NT, Wilson RS, Beck TL, Bienias JL, & Bennett DA Motor dysfunction in mild cognitive impairment and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Archives of Neurology. 2006; 63(12), 1763–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Stark SL, Roe CM, Grant EA, Hollingsworth H, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, et al. Preclinical Alzheimer disease and risk of falls. Neurology. 2013; 81(5), 437–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lin FR Hearing loss and cognition among older adults in the United States. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2011; 66(10), 1131–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Rogers MA, & Langa KM Untreated poor vision: a contributing factor to late-life dementia. American journal of epidemiology. 2010; 171(6), 728–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Geda YE, Cha RH, Pankratz VS, et al. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment is higher in men: The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology. 2010; 75(10), 889–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Johnson KA, Schultz A, Betensky RA, Becker JA, Sepulcre J, Rentz D, et al. Tau positron emission tomographic imaging in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Annals of neurology. 2016; 79(1), 110–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Lawrence E, Vegvari C, Ower A, Hadjichrysanthou C, De Wolf F, & Anderson RM A Systematic review of longitudinal studies which measure Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Alzheimers Dement. 2017; 59(4): 1359–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data associated with the Knight ADRC is available on request, via www.knightadrc.wustl.edu/Research/ResourceRequest.htm. Details regarding the number of participants who had each biomarker modality and the number of repeated data points is provided within Supplemental Tables 1–4.