Abstract

Purpose

From 1991 to 2018, binge drinking among U.S. adolescents has precipitously declined; since 2012, depressive symptoms among U.S. adolescents have sharply increased. Binge drinking and depressive symptoms have historically been correlated, thus understanding whether there are dynamic changes in their association informs prevention and intervention.

Methods

Data were drawn from the U.S. nationally representative cross-sectional Monitoring the Future surveys (1991–2018) among school-attending 12th-grade adolescents (N = 58,444). Binge drinking was measured as any occasion of more than five drinks/past 2 weeks; depressive symptoms were measured with four items (e.g., belief that life is meaningless or hopeless), dichotomized at 75th percentile. Time-varying effect modeling was conducted by sex, race/ethnicity, and parental education.

Results

In 1991, adolescents with high depressive symptoms had 1.74 times the odds of binge drinking (95% confidence interval 1.54–1.97); by 2018, the strength of association between depressive symptoms and binge drinking among 12th-grade adolescents declined 24% among girls and 25% among boys. There has been no significant relation between depressive symptoms and binge drinking among boys since 2009; among girls, the relationship has been positive throughout most of the study period, with no significant relationship from 2016 to 2017.

Conclusions

Diverging trends between depressive symptoms and alcohol use among youth are coupled with declines in the strength of their comorbidity. This suggests that underlying drivers of recent diverging population trends are likely distinct and indicates that the nature of comorbidity between substance use and mental health may need to be reconceptualized for recent and future cohorts.

Keywords: Adolescent depression, Binge drinking, TVEM

Mental health among teens has appeared stable throughout most of the past half-century [1], but accumulating evidence indicates unprecedented increases in mental health problems in the past decade. The estimated U.S. national prevalence of major depressive episodes has increased from 8.7% to 12.5% among adolescents from 2005 to 2015 [2], with the largest increases since 2012. These trends are corroborated in other national data; in the Monitoring the Future (MTF) study [3], mean depressive symptoms were stable from 1991 to 2012 and then began precipitously increasing in 2013 through 2018 [4]. Serious symptoms of depression include suicidal behavior, and the prevalence of adolescents seriously considering suicide, which decreased throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, abruptly increased after 2009 (13.8% in 2009 and 17.7% in 2015) [5]. These increases parallel observed increases in completed suicide as well [6]. Given these rapid and rather sudden increases in depressive symptoms and related outcomes, addressing adolescent mental health problems is an increasingly urgent public health priority.

Correlates of adolescent binge drinking are extensive and multileveled [7]. Heavy alcohol use is historically correlated with depression [8,9] in part because adolescents may self-medicate depression symptoms with alcohol and in part because heavy alcohol use may cause or exacerbate symptoms of depression [10]. Given the correlation between depressive symptoms and alcohol use, we may expect that these increases in depression have been related to increases in alcohol use across the last decade. However, alcohol use among adolescents has been consistently decreasing and has been for decades before the increase in depressive symptoms [3,11 ]. The picture that emerges for adolescents is striking in two distinct respects. First, although depressive symptoms are increasing, alcohol use is at a historic low, suggesting that the population-based mental health picture of today’s youth does not follow historical correlation patterns between mental health and substance use. Second, the trends observed among adolescents differ from the trends observed among adults, among whom alcohol consumption and disorders are increasing [12], suggesting some consistency in the historical pattern of relationship between mental health and substance use for adults but not teens.

A relevant question, with substantial public health implications, is whether diverging population-level trends in depressive symptoms and binge drinking are changing the relationship between binge drinking and depressive symptoms among youth. There are two possible scenarios: increased connection or decoupling. Increased connection would suggest that the relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking is getting stronger over time. As alcohol use declines overall, those remaining in the user pool may have a greater risk for mental health problems. As an analogy, adults who smoke cigarettes and are nicotine dependent now have more mental health problems than in previous generations when smoking was more common [13]. If teens who binge drink during this period of low use are at greater risk for depressive symptoms than previous generations, they could be driving increases in depressive symptoms and suicidal behavior, given the potentially fatal mix of mood disorders and alcohol use [14]. Decoupling would suggest that the relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking is getting weaker over time. Decoupling could occur if the underlying drivers of trends in depressive symptoms and alcohol use are becoming more distinct; for example, if alcohol use is declining because of effective health policy around availability and access, and depressive symptoms are increasing because of new and emerging risk factors such as cyberbullying, then binge drinking may not be as salient a risk factor now as it was historically. Such a finding would also have public health significance, as it would imply that the underlying mechanisms driving trends are becoming disparate and should be addressed separately.

Importantly, by examining depressive symptoms and binge drinking separately, without considering their association over time, we may be missing the full picture of what is driving the increases in depressive symptoms and decreases in alcohol use. Furthermore, both the increases in depressive symptoms and the decreases in alcohol use and binge drinking have not been consistent across demographic groups. For example, increases in depressive symptoms have been faster for girls [2], and decreases in binge drinking have been faster for boys [3]. Differences in rapidity of increases and decreases are also apparent across race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status [15].

The present study examines time trends in the strength of the relationship between binge drinking and depressive symptoms among nationally representative samples of adolescents from 1991 to 2018 in the MTF data, including examination of subgroup differences by sex, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.

Methods

Sample

Data were drawn from the MTF study, including annual cross-sectional surveys 12th-grade adolescents in the 48 contiguous U.S. states; we include data from 1991 to 2018 [3]. Schools are selected under a multistage random sampling design and are invited to participate for 2 years. Schools that decline participation are replaced with schools that are similar in geographic location, size, and urbanicity. The overall school participation rates (including replacements of schools that decline to participate) range from 91% to 99% for all study years. Student response rates have ranged from 85.0% to 87.3% and averaged 86.5%, with no systematic trend. Almost all nonresponse is because of absenteeism; <1% of students refuse to participate. Self- administered questionnaires are given to students. A detailed description of design and procedures are provided elsewhere [3,16]. The present study focuses on the 12th-grade students who were randomized to the consistent questionnaire form that included questions regarding depressive symptoms from 1991 to 2018 and who answered at least three of four depressive symptom questions. The total eligible sample size was 68,670. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan approved the study procedures, and the Institutional Review Board of the Columbia University approved the secondary data analysis for this article.

Measures

Depressive symptoms

Four items were used to measure depressive symptoms, 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree) at the time of the survey. After the stem questions “How much do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements,” respondents assessed the following items: “Life often seems meaningless,” “The future often seems hopeless,” “It feels good to be alive,” and “I enjoy life as much as anyone.” The latter two questions were reverse coded for analysis. These items were chosen based on psychometric analyses, suggesting that they have high internal reliability, and they have been used in previous studies of these data, for example, a study by Maslowsky et al. [17]. Scores were summed to create a total score. Respondents missing data on one of the four items (1.60%) were imputed with the mean value of the other three; respondents missing data on two or more of the four items (10.42%) were excluded from the analysis. Scores ranged from 4 to 20 with a mean of 7.61 (standard deviation [SD] = 3.50) and a median of 7.0, indicating that the mean and median scores were close to the “disagree somewhat” response on the negatively worded items (2 on the response scale).

The depressive symptoms score was nonnormally distributed, with right skewness. Therefore, for the purpose of analysis, depressive symptoms were dichotomized at the 75th percentile to estimate trends in the proportion who endorse higher than average depressive symptoms. As a sensitivity analysis, we also dichotomized depressive symptoms at the median, as well as the 90th percentile, to determine any variation in the results as a consequence of dichotomization decision.

Past 2-week binge drinking

All adolescents were queried on the number of occasions they consumed five or more drinks “in a row” in the past 2 weeks (other time frames were not assessed). Of the 12th graders who were assigned the form measuring depressive symptoms, 6.96% were missing on this question. Binge drinking was dichotomized as more than 1 occasion in the past 2 weeks versus none. Although criteria for binge drinking often use separate cut points by sex, in the present study used more than five drinks for both boys and girls because it was consistently measured with no variation in question wording throughout the study period of 1991 to the present.

Demographics

Analyses were stratified by respondent-identified sex (male: 47.3%), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white: 66.2%; non-Hispanic black: 11.9%; Hispanic: 12.5%; other racial/ethnic subgroups were too small for reliable estimation by year), and parental education (a proxy for socioeconomic status), measured as the highest level of education of either the mother or the father (4 year college or greater, 52.2%, vs. less, 47.9%).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics and yearly prevalence estimates were estimated using SAS v14.1 (SAS Institute, Inc). For time-varying associations between binge drinking and depressive symptoms, we used time-varying effect modeling (TVEM). TVEM is a flexible modeling framework that assesses the functional form of the relationship between covariates and outcomes over continuous time without making assumptions about the parametric form [18,19]. One assumption of TVEM is that the change in the relationship over time is smooth (rather than abrupt) [20]. We used the SAS macro %TVEM [21].

Although we assumed that the relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking is bidirectional and reciprocal, we modeled depressive symptoms as a risk factor for binge drinking (for which there is evidence in the literature) [22]. We fit logistic regression models for each year with year as a continuous, flexible smoothed function of time from 1991 to 2018. Two knots were used to fit the splines in the TVEM figures. The knots were positioned on evenly distributed quantiles across time.

We use figures to present coefficient functions that show point-wise confidence intervals (CIs); the 0 line is dashed to indicate a null relationship. Empirical sandwich estimators were used such that parametric assumptions were not made, and P-splines were estimated to describe the functional form of time in the relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking [20]. All analyses incorporated MTF sampling weights.

Results

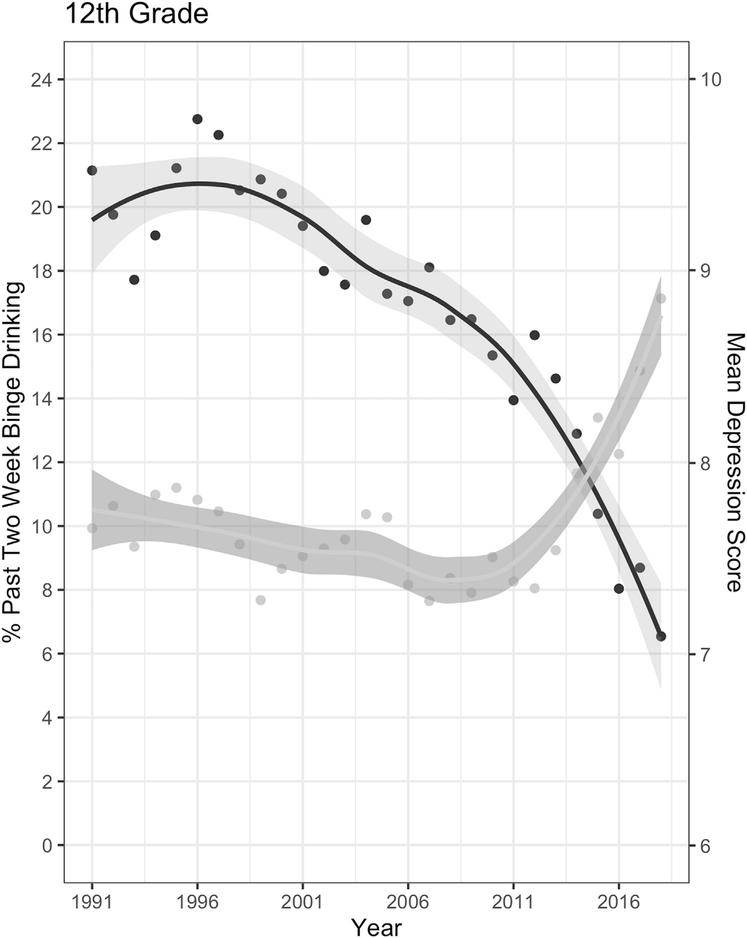

Figure 1 describes the prevalence of binge drinking and the mean depressive symptoms by year. The prevalence of any binge drinking has declined consistently from 1991 to 2018, from 21.73% in 1997 to 7.96% in 2018. In contrast, depressive symptoms were relatively stable from 1991 to 2013. After 2013, mean depressive symptoms increased from 8.02 (SD = 3.78) in 2014 to 8.86 (SD = 3.86) in 2018. Supplementary Figures 1–3 provides the trends stratified by sex, race, and parental education.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of mean depressive symptom score (right axis) and past 2-week binge drinking (left axis) among adolescents in 12th grade (N = 58,444).

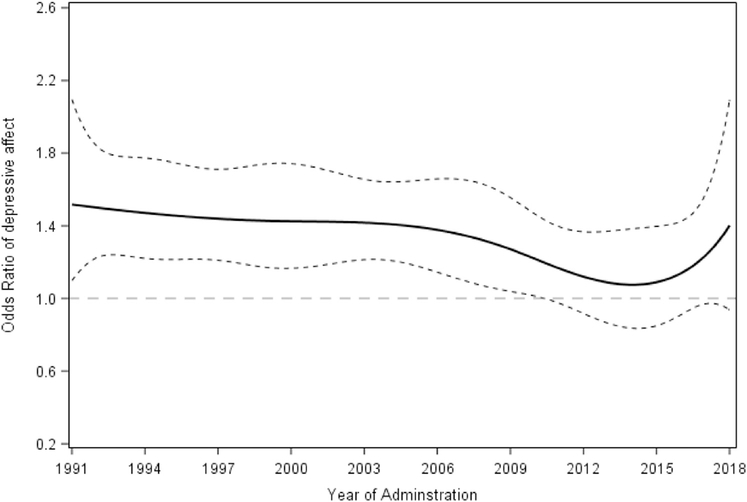

Figure 2 displays the multivariable time-varying linear regression estimates, including demographic covariates, for the association between binge drinking and depressive symptoms (high vs. low at the 75th percentile) from the TVEM algorithm. Those with high depressive symptoms had 1.74 times the odds of binge drinking (95% CI 1.54–1.97) compared with those with low/no depressive symptoms in 1991. The coefficient of the relationship varied each year, and, in general, the magnitude was lower in more recent years; there was no relationship between binge drinking and depressive symptoms from 2014 to 2016. Most recently, in 2018, those with high depressive symptoms had 1.46 times the odds of binge drinking (95% CI 1.18–1.82) compared with those with low/no depressive symptoms. Overall, comparing the magnitude of the relationship from 1991 to 2018, there was a 16.1 percentage point decrease in the coefficient of the relationship between binge drinking and depressive symptoms.

Figure 2.

Time-varying associations between depressive symptoms and past 2-week binge drinking among 12th students, 1991–2018. N = 58,444. Dotted lines indicate 95% confidence intervals; dotted line at 0 indicates null (no association). For specific time points when confidence intervals do not contain 1.0, the coefficient is significant at p < .05.

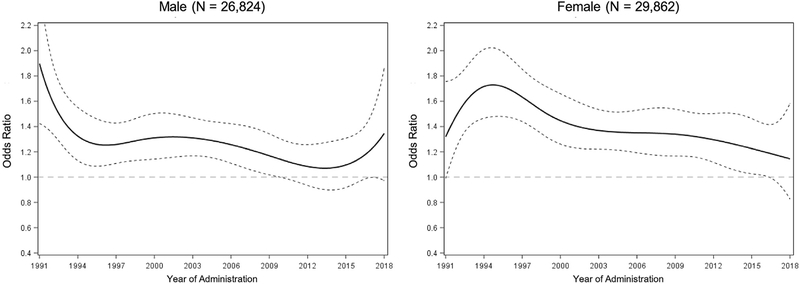

The relationship between binge drinking and depressive symptoms was heterogeneous across years by sex. There was evidence of interaction between sex and binge drinking across years between 1992 and 2001, as well as 2014–2015. We present results stratified by sex in Figure 3. For boys, the relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking was 1.72 (95% CI 1.35–2.19) in 1991 and remained positive for each year until 2009. After 2009 to 2018, the relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking was nonsignificant. Among girls, the year with the strongest magnitude of relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking was 1995, with an odds ratio of 1.70 (95% CI 1.49–1.94). After 2016 to 2018, the relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking was close to the null. Overall, comparing the magnitude of the relationship from 1991 to 2018, there was a 25.0 percentage point decrease in the coefficient of the relationship among boys, and 24.1 percentage point decrease in the coefficient of the relationship among girls.

Figure 3.

Time-varying associations between depressive symptoms and past 2-week binge drinking among U.S. 12th-grade students, 1991e2018, stratified by sex. Dotted lines indicate 95% confidence intervals; dotted line at 0 indicates null (no association). For specific time points when confidence intervals do not contain 1.0, the coefficient is significant at p < .05. There was evidence of interaction between parental education and depression between 1994 and 1997.

We also examined interaction by parental education and by race/ethnicity. Stratified results are shown in Supplementary Figures 4 and 5. By parental education (Supplementary Figure 4), the figures suggest that the peak of the relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking was highest and in 1991 for those with low parental education and in 1997 for those with high parental education; there was little evidence of a relation between depressive symptoms and binge drinking after 2010 among those with low parental education and after 2016 among those with high parental education. By race (Supplementary Figure 5), among white students, the relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking was highest in 2001, and then declined, especially after 2016. Among black students, the relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking was highest in 1991 and nonsignificant after 2006 (with some evidence of an inverse relationship in 2011). Among Hispanic students, the relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking was highest in 1995 and included the null between 2000 and 2009, as well as in 2017–2018. However, interaction tests indicated no differences in the coefficient of the relationship across the years between depressive symptoms and binge drinking comparing white and black students; comparing white and Hispanic students, there was an interaction with the odds ratios being significantly lower for Hispanic students in 2003–2006.

Finally, as an additional sensitivity analysis, we dichotomized depressive symptoms at the 90 percentile (Supplementary Figure 6, overall sample, Figures 7–9 for each subgroup by sex, race, and education), as well as the median (Supplementary Figure 10, overall sample, Figures 11–13 for each subgroup by sex, race/ethnicity, and education). Regardless of the dichotomization used, the results were consistent in demonstrating a decline in the strength of the relationship between binge drinking and depressive symptoms, with consistent results showing the relationship weakened for boys earlier than for girls, and similar structure of heterogeneity by parental education and race/ethnicity.

Discussion

From 1991 to 2018, binge drinking among U.S. adolescents has precipitously declined; since 2012 to 2018, depressive symptoms among U.S. adolescents have sharply increased. The present study demonstrates that within these two diverging trends, a new trend is also apparent: the relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking among 12th-grade adolescents has weakened. More specifically, the strength of the relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking decreased by 16% from 1991 to 2018 and 24%–25% among both boys and girls. The changes in the relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking were not homogenous across demographic subgroups, especially by sex. For girls, although there have been declines in the magnitude of the relationship between depressive symptoms and binge drinking over time, there was a significant positive relationship overall until 2017. For boys, the association became nonsignificant earlier, in 2010.

These results suggest that as mental health and substance use dynamically shift for the current generation of adolescents, so too do patterns of comorbidity established earlier. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have consistently reported that binge and frequent drinking are associated with onset of symptoms of major depression in adolescence [23,24]. Although some studies [25,26] suggest a dose–response relationship between frequency of alcohol and other drug use and internalizing symptoms, most indicate that the relationship is stable across levels of alcohol consumption [27,28]. Although there are no direct tests of the declines in the magnitude of the relation between binge drinking and depressive symptoms across time, a suggestive examination of the decline indicates that it began in the late 1990s, before the increase in depressive symptoms among U.S. adolescents. More broadly, our results suggest that a rethinking of comorbidity between mental health and alcohol use is warranted.

Sex differences in the magnitudes of association over time should be carefully considered. Existing literature indicates that the increases in depressive symptoms observed in adolescence are almost exclusively restricted to girls [2,4]. Furthermore, declines in binge drinking have been much more concentrated among boys compared with girls [3]. Taken together, mental health problems among girls are increasing, and drinking patterns are not decreasing at the same rates as boys. Indeed, we find that although depressive symptoms and binge drinking have not been associated with each other among 12th-grade boys in almost a decade, they remained associated among girls until 2017, suggesting that 12th-grade girls in the past decade are increasingly experiencing mental health problems and problematic drinking patterns. Although the present analyses focused on the total association between depressive symptoms and binge drinking controlling for demographic indicators, alcohol use and depressive symptoms are produced by a wide range of causes including other substance use, peer and parent influences, and social context; understanding the heterogeneity in comorbidity across multiple levels of organization can guide prevention and intervention efforts and is an important direction of continued comorbidity research. Furthermore, disentangling the determinants of individual-level variation (i.e., why some adolescents binge drink and some do not) versus determinants of cross-time variation (i.e., why binge drinking is higher in some years than others) is important to identify drivers of population- level trends. Changes in the prevalence and magnitude of risk factors can affect estimates of comorbidity because base rates may be affected across time; thus, assessments of comorbidity are always tied to prevalence levels of each component of the comorbidity assessment.

It is also worth noting that substance use patterns that begin early in life are predictive of later life outcomes. Available evidence indicates that among adults, especially women, those in middle age are increasing binge drinking and alcohol problems faster than previous generations of women at that age [29–31], and faster than other age groups (indicative of a cohort effect). Those women in middle age now are among the cohorts of high school seniors in the mid-1990s, the group who had the strongest magnitude of association between depressive symptoms and binge drinking when they were teenagers. Those patterns established early in the life course may have been foreshadowing the experience of these women as they age today. Overall, these results underscore that to understand the health patterns of adults, a life course approach that attends to early life patterns of mental health and comorbidity is necessary.

The reasons that binge drinking has declined among U.S. adolescents include the long-term effects of major policy changes such as increasingly the minimum legal drinking age to 21 years (finalized in all states by 1986) [32]. Previous work has shown that although binge drinking in adolescence has declined, these declines were shifted to increases in binge drinking during the transition to adulthood [33,34] and an increase in the age of peak binge drinking prevalence [35], concomitant with social changes such as increased attendance at 4-year colleges (which increases risk of binge drinking among young adults), and delay of marriage and childbearing (which decrease risk of binge drinking). These reasons are likely distinct from the underlying drivers of the increases in depressive symptoms among adolescents in the past decade. Such increases have been observed in multiple datasets and include increases in major depression [2], suicidal behavior [5], and completed suicide [6]. Although changes in the landscape of how adolescents interact (e.g., use of technology, smartphones, and social media) have been hypothesized to underlie some of the increases in depressive symptoms (given that it facilitates envy, negative self-worth, and cyberbullying) [36], most rigorous analyses suggest that such technologies promote positive social and emotional development [37]. Investigating varying exposures across the social landscape is critical not only for intervening on and preventing depressive symptoms and substance use but also potentially for the recognition that such exposures are fundamentally changing observed patterns of comorbidity that are assumed to be stable.

Study limitations are noted. All data are based on self-report, including binge drinking, which may be under- or over-reported by adolescents; however, we expect that under- and over-reporting are constant across historical time. MTF measures have been used for decades, and evidence indicates adequate psychometric properties [38]. Measures of binge drinking typically include a cut point of four or more drinks among girls and women (rather than more than five, as included here); however, the MTF data did not have a more than four measures available for all years and did not include a measure of more than four in the same questionnaire forms as the measures of depressive symptoms; thus, we could not assess binge drinking differently by sex. Depressive symptoms in MTF are measured with four items, which are not clinical measures and are based on self-report. The limitations of the measure of depressive symptoms are off-set by the strength that question wording is invariant across time, but we cannot rule out possible changes in students’ comfort in revealing or acknowledging depressive symptoms as potentially contributing to responses. However, students are instructed that responses will remain confidential; furthermore, the MTF study has many questions that are sensitive in nature, and we have found no evidence of systematic trends that would be consistent with changing willingness to be candid [3]. We do not have information on whether adolescents have used services for depressive symptoms, but note that a small proportion of individuals with depression or any mental health problem access treatment services [39], suggesting that treatment utilization is unlikely to have a large impact on population mean symptoms. The time frame of depressive symptoms was current at the time of the survey; depressive symptoms are likely more variable over other time frames (e.g., over the past year); binge drinking was assessed in the prior 2 weeks, thus temporally concurrent with depressive symptoms in the MTF survey. Assessments over longer time frames may yield different associations, which should be assessed in data sources with varying time frames as extensions of the present analysis. Missing data on covariates ranged from 3.1% for sex to 12.4% for race; we did not consider multiple imputation in these models as TVEM algorithms do not currently support multiple imputed data, but as the methods progress, assumptions about data missing at random can be relaxed. Furthermore, the MTF study excludes those who have dropped out of high school. This should have a modest effect on those in grade 12, given that the majority of adolescents at this age remain in school [3]; however, we note that these results are generalizable to high school–attending target populations of adolescents. Finally, we modeled depressive symptoms as the independent variable and binge drinking as the outcome variable in these analyses, but the relation is reciprocal, with increased binge drinking also associated with more depressive symptoms. As such, the estimates here should be interpreted as the total association; we are not claiming to estimate the causal relationship separating out the pathways between depressive symptoms and binge drinking and vice versa.

In summary, these results suggest that, on average, the relationship between binge drinking and depressive symptoms is dynamically changing and decoupling. Although the underlying etiology of the comorbidity between alcohol consumption and mental health is complex, the landscape of the adolescent experience is changing in ways that may affect both consumption and mental health. The declining correlation between binge drinking and mental health is occurring during a time of unprecedented decreases in alcohol consumption among U.S. adolescents and increases in mental health problems. The nature of comorbidity between substance use and mental health may need to be reconceptualized for recent and future cohorts.

Supplementary Material

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

The strength of the relationship between binge drinking and depressive symptoms is declining, suggesting that depressive symptoms are no longer a risk factor for binge drinking in adolescence. Depressive symptoms continue to rapidly escalate among U.S. adolescents, and understanding changes in comorbidity is essential to developing interventions.

Acknowledgements

Authors’ Contributions: K.M.K. conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial article, and reviewed and revised the article. A.H. conducted the data analysis and drafted sections of the original article, as well as reviewed and revised it. M.E.P. supervised data collection and methodology and provided critical feedback on manuscript drafts. J.S. assisted in the design and implementation of the parent study and provided critical feedback and revisions on the analysis plan and manuscript drafts. All authors approved the final article as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding Sources

The Monitoring the Future study is funded by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R01001411. Analyses were also funded by R01DA037902 (M.E.P.) and R01AA026861 (K.M.K.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.08.026.

References

- [1].Jane Costello E, Erkanli A, Angold A. Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip 2006;47: 1263–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics 2016;138: e20161878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Miech RAA, Johnston LDD, O’Malley PMM, et al. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2017: Volume I, secondary school students. Ann Arbor Inst Soc Res Univ Michigan; Available at: Http//MonitoringthefutureOrg/PubsHtml#monographs 2018. Accessed August 6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Keyes KM, Gary D, O’Malley PM, et al. Recent increases in depressive symptoms among US adolescents: Trends from 1991–2018. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2019;54:987–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].CDC. Trends in the prevalence of suicide-related behavior national YRBS: 1991–2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/2015_us_suicide_trend_yrbs.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2018.

- [6].Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increases in suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. NCHS Data Brief 2016:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull 2017;143: 187–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pirkola SP, Marttunen MJ, Henriksson MM, et al. Alcohol-related problems among adolescent suicides in Finland. Alcohol Alcohol 1999;34:320–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Foley DL, Goldston DB, Costello EJ, et al. Proximal psychiatric risk factors for suicidality in youth: The Great Smoky Mountains study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:1017–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wilkinson AL, Halpern CT, Herring AH. Directions of the relationship between substance use and depressive symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood. Addict Behav 2016;60:64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].CDC. Trends in the prevalence of alcohol use | National YRBS: 1991–2015.2016.

- [12].Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001–2002 to 2012–2013: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74:911–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Talati A, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. Changing relationships between smoking and psychiatric disorders across twentieth century birth cohorts: Clinical and research implications. Mol Psychiatry 2016;21:464–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Brent DA, Baugher M, Bridge J, et al. Age- and sex-related risk factors for adolescent suicide. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38:1497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Jang JB, Patrick ME, Keyes KM, et al. Frequent binge drinking among US adolescents, 1991 to 2015. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20164023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, et al. The Monitoring the Future project after four decades: Design and procedures. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Maslowsky J, Schulenberg JE, Zucker RA. Influence of conduct problems and depressive symptomatology on adolescent substance use: Developmentally proximal versus distal effects. Dev Psychol 2014;50:1179–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lanza ST, Vasilenko SA, Liu X, et al. Advancing the understanding of craving during smoking cessation attempts: A demonstration of the time-varying effect model. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16(Suppl 2):S127–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tan X, Shiyko MP, Li R, et al. A time-varying effect model for intensive longitudinal data. Psychol Methods 2012;17:61–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Li R, Dziak JJ, Tan X, et al. TVEM (Time-varying effect modeling) SAS macro users’ guide (version 3.1.0). Methodol Center, Penn Statez, Univ Park PA: Available at: https://methodology.psu.edu/sites/default/files/software/tvem/TVEM_310.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Keyes KM, Brady J, Li G. Effects of minimum legal drinking age on alcohol and marijuana use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2015;39:194A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dir AL, Bell RL, Adams ZW, Hulvershorn LA. Gender differences in risk factors for adolescent binge drinking and implications for intervention and prevention. Front Psychiatry 2017;8:289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pedrelli P, Shapero B, Archibald A, Dale C. Alcohol use and depression during adolescence and young adulthood: A summary and interpretation of mixed findings. Curr Addict Rep 2016;3:91–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cairns KE, Yap MBH, Pilkington PD, et al. Risk and protective factors for depression that adolescents can modify: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord 2014;169:61–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hussong AM, Jones DJ, Stein GL, et al. An internalizing pathway to alcohol use and disorder. Psychol Addict Behav 2011;25:390–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Boden JM, Fergusson DM. Alcohol and depression. Addiction 2011;106: 906–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction 2004; 99:1548–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Goodman A. Substance use and common child mental health problems: Examining longitudinal associations in a British sample. Addiction 2010; 105:1484–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Ye Y, et al. Are the 1976–1985 birth cohorts heavier drinkers? Age-period-cohort analyses of the national alcohol surveys 1979–2010. Addiction 2013;108:1038–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Keyes KM, Miech R. Age, period, and cohort effects in heavy episodic drinking in the US from 1985 to 2009. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;132: 140–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].White A, Castle I-JP, Chen CM, et al. Converging patterns of alcohol use and related outcomes among females and males in the United States, 2002 to 2012. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2015;39:1712–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Keyes KM, Jager J, Hamilton A, et al. National multi-cohort time trends in adolescent risk preference and the relation with substance use and problem behavior from 1976 to 2011. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;155: 267–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jager J, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, et al. Historical variation in rates of change in substance use across the transition to adulthood: The trend towards lower intercepts and steeper slopes. Dev Psychopathol 2013;25: 527–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jager J, Keyes KM, Schulenberg JE. Historical variation in young adult binge drinking trajectories and its link to historical variation in social roles and minimum legal drinking age. Dev Psychol 2015;51:962–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Patrick ME, Terry-McElrath YM, Lanza ST, et al. Shifting age of peak binge drinking prevalence: Historical changes in normative trajectories among young adults aged 18 to 30. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2019;43:287–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bottino SMB, Bottino CMC, Regina CG, et al. Cyberbullying and adolescent mental health: Systematic review. Cad Saude Publica 2015;31:463–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Odgers C. Smartphones are bad for some teens, not all. Nature 2018;554: 432–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Miech R, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, et al. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2018, Volume I; 2019. Secondary school students. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, et al. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcoholism and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:1097–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.