“In questions of science, the authority of a thousand may not exceed the humble and careful reasoning of on individual.” Galileo Galilei

The Covid (coronavirus-associated disease)-19 pandemic continues to grip the world in both overt and covert ways- not unexpected from a nearly invisible (0.1 µm RNA virus) and sinister foe with light-speed mutation rates and host-switching capabilities [1]. While containment of the SARS (serious acute respiratory syndrome)-CoV-2 virus remains the highest priority from city, region, state and country-wide perspectives, attention to treatment that includes strategies capable of preventing Covid-19 clinical acuity esculation and the management of critically ill patients as well as wide-scale testing must proceed rapidly in parallel. The medical community must learn from lessons illustrated from cases around the world, including the earliest experiences [2]. The following Covid-19 treatment update is dedicated to pharmacologic therapies, their mechanism(s) of potential benefit, safety considerations and optimal study design for planned and ongoing clinical trials. The focus is on chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine- two oral drugs that have been available and used widely for the prevention and treatment of malaria and in the management of autoimmune diseases. Both drugs are currently inexpensive. The public health emergency caused by Covid-19 is a call to action as the scientific community embraces its role and shows through selfless rigor, collaboration, compassion and resolve the power of science to heal and to comfort. In the process of seeking answers to complex questions of import near and far we must endeavor always to be guided by facts and both irrefutable and reproducible scientific evidence.

Potential therapies for Covid-19

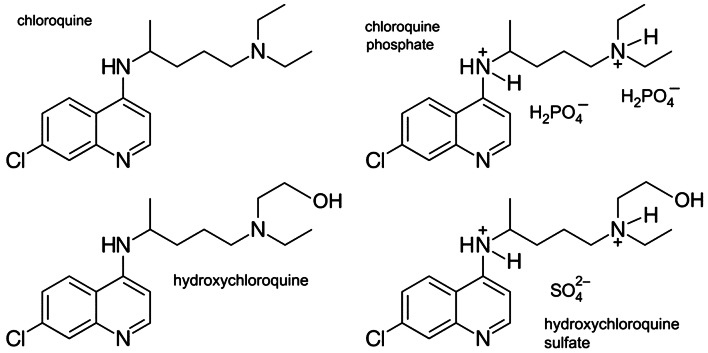

There is not an FDA-approved treatment for COVID-19 at this time; however, high-level effort and investigations remain and are in progress, respectively. Taking a SARS-CoV-2 specific approach to drug development is logical and was recently summarized by Kupferschmidt et al. [3] (Fig. 1). While estimates of the current number of planned and ongoing clinical trials vary, it may be as many as 800 worldwide (INFO@WCGCLINICAL.COM). Appropriations for research and development in the United States under the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Act (H.R. 6074) Title III of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES Act)- P.L.116–136 (H.R. 478) are approximately $2 billion USD (www.congress.gov).

Fig. 1.

Targeted approach to drug development for SARS-CoV-2. The lines of attack against SARS-CoV-2, numbered 1–6, include inhibition of: (1) fusion; (2) translation; (3) proteolysis; (4) translation and RNA replication; (5) packaging and; (6) virion release. From Kupferschmidt and Cohen [3]. With permission

On March 28, 2020 the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA issued) an emergency use authorization (EUA) permitting chloroquine phosphate (medical grade) and hydroxychloroquine sulfate to be added to the strategic national stockpile (SNS) (Fig. 2). The SNS exists under the authority of the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and accepted 30 million doses of hydroxychloroquine sulfate donated by Sandoz™, the Novartis™ generics and biosimilars division, and one million doses of chloroquine phosphate donated by Bayer Pharmaceuticals™ for potential use in treating patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 or for use in clinical trials. In addition to the SNS donations, these companies and potentially others could offer additional doses (www.fda.gov). There was an expectation that companies would increase production for the commercial market as well to avoid shortages for patients with autoimmune disease who rely on hydroxychloroquine sulfate (Plaquenil®) for routine treatment [4].

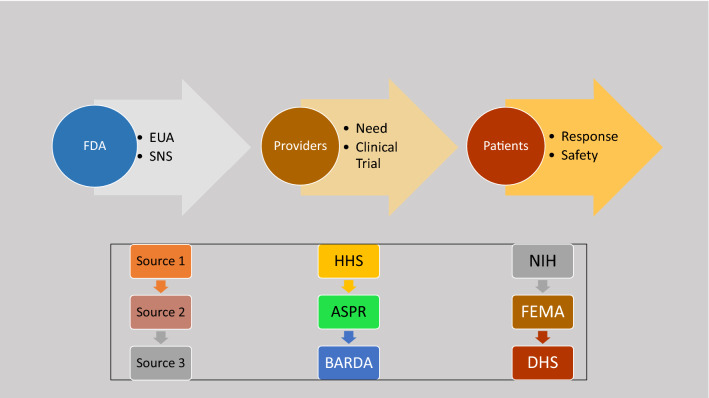

Fig. 2.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine compounds. Molecular structures of chloroquine and chloroquine phosphate (upper panels) and hydroxychloroquine and hydroxychloroquine sulfate

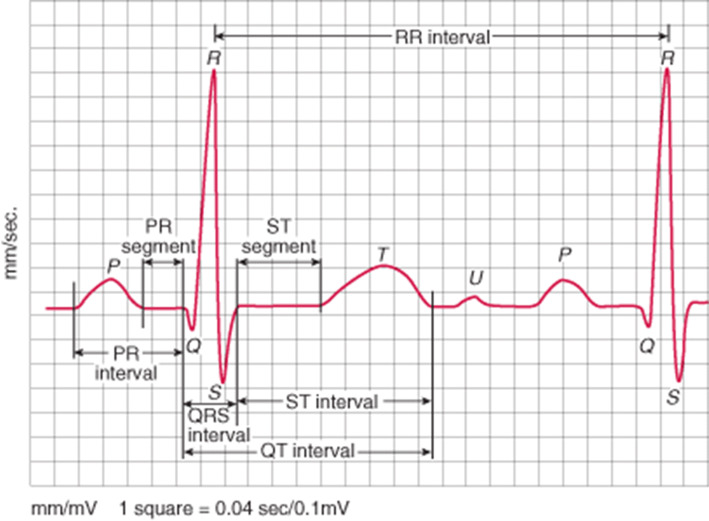

The coordinated use of chloroquine phosphate and hydroxychloroquine sulfate is governed by the HHS office of the Assistant Secretary of Preparedness and Response (ASPR). In turn, APSR’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) works collaboratively with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and FDA to assure safety and the drugs appropriate use to include well-designed clinical trials (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

A Step-Wise Approach to Securing Drug Availability in Public Health Emergencies in the United States. There are several steps and over-sight required to make drugs available for use during a public health crisis. To be successful, each step and a high level of coordination is needed (see text). FDA Food and Drug Administration; EUA Emergency use authorization; HHS Health and Human Services; ASPR Assistant Secretary of Preparedness and Response; BARDA Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority; FEMA Federal Emergency Management Authority; DHS Department of Homeland Security

The EUA grants permission to BARDA allowing chloroquine phosphate and hydroxychloroquine sulfate to be distributed and prescribed by physicians to hospitalized teen and adult patients with Covid-19, when deemed appropriate, if a clinical trial is either not available or feasible. The EUA mandates that fact sheets summarizing important information about the drugs and their administration are made availability to patients and prescribers, including potential risk and drug interactions. Drug shipments to individual states is overseen by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) who works closely with the Department of State and Department of Homeland Security to secure donated shipments.

What is chloroquine, how does it work and why might it be effective in the treatment of COVID-19?

Chloroquine was discovered in the early 1930′s by Hans Andersag, a scientists working for Bayer AG™ on compounds with anti-malarial properties. It is a 4-aminoquinoline compound taken by mouth and has a long track record of mass administration for the prevention of malaria to include plasmodium vivax, plasmodium ovale and plasmodium malariae. It is typically not used for plasmodium falciparum given well-documented resistance [5].

Chloroquine is absorbed rapidly and has a wide volume of distribution and undergoes hepatic metabolism giving rise to its primary metabolite desethylchloroquine. Approximately, 50% of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine.

Mechanism of action

Chloroquine accumulates within lysosomes where it alters cellular pH and is stored in a protonated form. The antiviral effect is believed to be from chloroquine’s ability to increase endosomal and lysosomal pH thereby attenuating the ability of the virus to release its genetic material into the cell and replicate. The drug also inhibits important post-translational steps in newly formed proteins, acts as a zinc ionophore that increases intracellular zinc concentration and inhibits RNA-dependent polymerases, decreases endosomal release of iron required for the replication of DNA and inhibits glycosylation of envelope glycoproteins (reviewed in Savarino [6]).

There has been interest in the potential antithrombotic effects of chloroquine. While the contribution to its overall benefit may be modest and largely unknown in patients with Covid-19, chloroquine reduces neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation, platelet aggregation and circulating tissue factor in mice [7].

Cardiovascular effects

Chloroquine has been shown to differentially modulate coronary arterial vasodilation in diabetic mice [8]. In humans, it decreases nitric oxide production in coronary artery endothelial cells. The potential clinical impact in patients with coronary artery disease is unknown. Chloroquine has been shown in animal models to inhibit autophagy with a resulting improvement in diastolic performance in diabetic mice [9]. The potential mechanism(s) of benefits include deceased autophagolysosomes, apoptosis and cardiac fibrosis.

Potential risks

Cardiovascular effects, including vasodilation, hypotension, decreased myocardial performance and arrhythmias have been reported following chloroquine administration at high doses (reviewed in Ben-Zvi [10]).

The potential cardiotoxic effects of chloroquine have been summarized by several groups. Blignaut and colleagues investigated several specific functional effects, including ex vivo myocardial performance and glucose uptake, mitochondrial function and in vivo heart function [11]. Control or obese male Wister rats were used in the experiments and exposed to varying concentrations of chloroquine. Doses that achieved a concentration of 10uM or higher decreased heart function. Ex vivo exposure did not affect mitochondrial function, but chronic exposure decreased cardiac output.

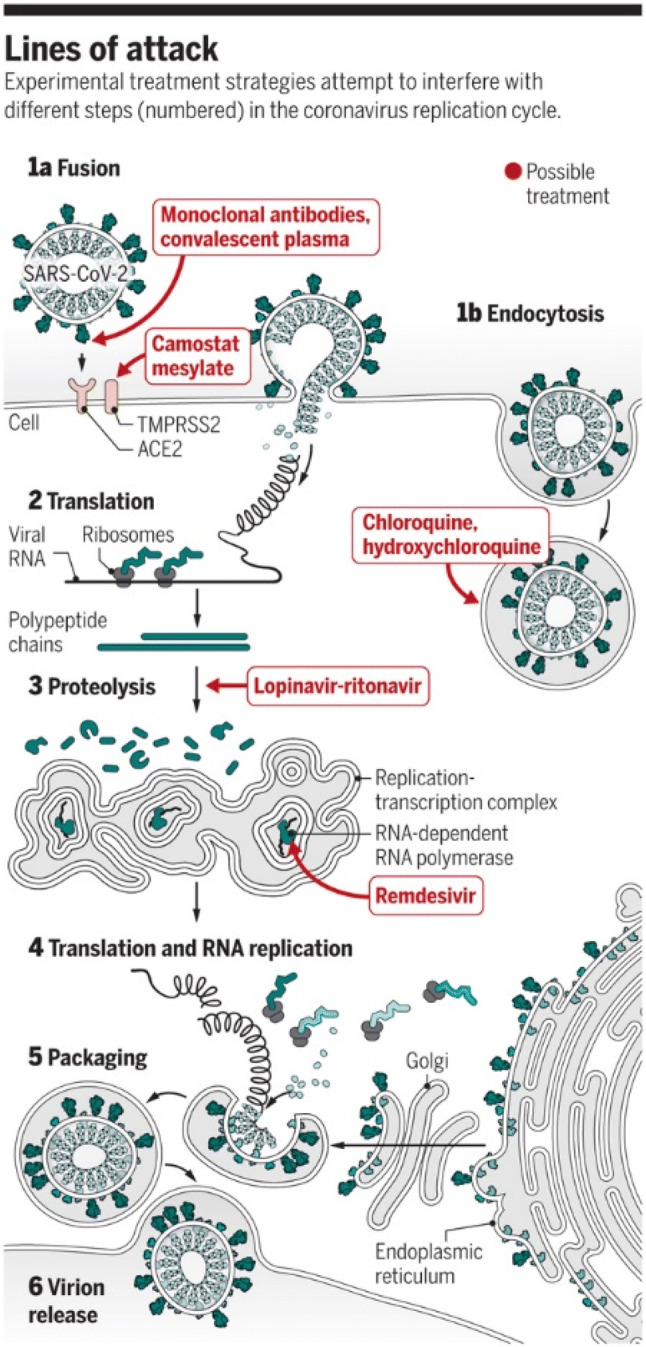

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) posted a warning on their website about non-medicinal chloroquine phosphate products and their potential risks to humans after ingestion, including death (www.cdc.com). It is also important to be mindful of and attentive to the potential risk of medicinal chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine (to be discussed) when taken in doses higher that recommended. Cardiac arrhythmias, including torsades de pointe ventricular tachycardia stemming from Q-Tc prolongation and often, but not always concomitant hypokalemia can occur (Figs. 4 and 5). Additional electrocardiographic effects include bundle branch block and atrioventricular (AV) block. Non-cardiovascular adverse effects that have been reported range from nausea, vomiting and diarrhea to thrombocytopenia, aplastic anemia, shock, seizures, coma and death.

Fig. 4.

Electrocardiographic QTc interval prolongation. The QT interval represents the period of ventricular depolarization (QRS interval) and repolarization (ST interval). It is corrected for the heart rate and referred to as the QTc interval. Prolongation of repolarization is caused by an increase of inward current through sodium or calcium channels or a decrease in outward current through potassium channels. The normal value in adults is 470 ms in men and 480 ms in women. The normal QTc interval is shorter in children. A sudden prolongation of QTc interval (greater than 20–30% above baseline) or an absolute value > 500 ms increases the risk for ventricular tachycardia that can be life-threatening. Other intervals, including the PR (atrial depolarization and conduction leading up to ventricular depolarization) are shown

Fig. 5.

Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia “Torsades de Pointes”. Torsades de Pointes or “twisting of the points or peaks” ventricular tachycardia occurs in the setting of a prolonged QTc interval that is either inherited or acquired or both. Some individuals with familial long QTc Syndrome (LQTS) are not aware of their condition and symptoms may not occur until a medication with QTc-prolonging capabilities is administered. The ventricular rate is fast and almost always causes low blood pressure and hemodynamic compromise. It is a cause of sudden cardiac death

Data supporting the investigation of chloroquine in Covid-19

There are in vitro data for chloroquine and SARS-CoV replication [12]. Kayaerts et al. tested its antiviral potential against SARS-CoV-induced cytopathicity in Vero E6 cell culture. The IC50 of chloroquine for antiviral activity (8.8 ± 1.2 μM) was significantly lower than its cytostatic activity; CC50 (261.3 ± 14.5 μM) and approximated the plasma concentrations commonly achieved during treatment of malaria. The same group [13] investigated whether chloroquine, provided either transplacentally or via maternal milk could prevent HCoV-OC43-induced death in newborn mice. The highest survival rate (98.6%) occurred when mother mice received 15 mg of chloroquine per kg of body weight daily.

Wang and colleagues [14] tested the in vitro antiviral activity of chloroquine in Vero E6 cells infected with nCoV-2019BetaCoV/Wuhan/WIV04/2019 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.05. Chloroquine (EC50 = 1.13 μM; CC50 > 100 μM, SI > 88.50) blocked virus infection at low-micromolar concentrations at both entry, and at post-entry stages.

Huang and colleagues [15] conducted a small pilot study in patients with Covid-19. A total of 22 patients were divided into two groups: one (n = 10) treated with chloroquine (500 mg, oral administration, twice daily) and another (n = 12) with lopinavir/ritonavir (400/100 mg, oral administration, twice daily) for 10 days and monitored for a total of 14 days. Chloroquine treated patients were more likely to turn negative for viral RNA. In fact, by day 13, all the chloroquine-treated patients became negative for viral RNA test. In the lopinavir/ritonavir treated patients, 11 out of 12 turned negative by Day 14. Improvement in pulmonary CT scans occurred at twice the rate in chloroquine-treated patients compared to those receiving lopinavar/ritonavir and duration of hospitalization was shorter in the former group as well. Serious adverse events were not reported in either treatment group.

What is hydroxychloroquine, how does it work and why might it be effective in the treatment of Covid-19?

Hydroxychloroquine was developed and subsequently approved for the treatment of malaria in 1955 (reviewed in Al-Bari; [16]). Like chloroquine, but with a better safety profile, particularly with prolonged use, it is included on the World Health Organization’s list of essential medications with indications for administration that have expanded over the years to include autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus and post-Lyme’s disease arthritis (reviewed in Plantone; [17]). Hydroxychloroquine exhibits anti-inflammatory, immunomodulating, anti-infective, antithrombotic, and metabolic effects. Hydroxychloroquine is absorbed rapidly after oral administration, metabolized by hepatic P450 enzymes and cleared by the kidneys.

Mechanism of action

As a result of its lipophilic properties and relatively high pH, hydroxychloroquine enters cell readily and accumulates within lysosomes. There is a resulting increase in pH from 4 to 6 that attenuates glycosylation and release of antigenic proteins, interference of lysosomal acidification, decreased macrophage cytokine production to include interleukins and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, antagonist effects on prostaglandins, binding and stabilizing of nucleic acids, inhibition of T and B-cell signaling, inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases [18–20], chemotaxis, superoxide production and phagocytosis of neutrophils, a reduction in Toll-like receptor signaling and attenuated activation of dendritic cells. Hydroxychloroquine has also been shown to bind cell surface sialic acid and gangliosides with high affinity, thereby impairing SARS-CoV-2 spike protein recognition and binding to host cell angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE)-2 receptors [21].

Cardiovascular effects

Hydroxychloroquine’s blockade of TNF-α has been associated with a reduction of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease-associated events among patients with autoimmune rheumatologic disease [22] (age adjusted rate ratio 0.46, 95% CI 0.25 – 0.85). Interleukin (IL)-1 inhibition has also been shown to reduce cardiovascular events (reviewed in Ali and Becker [23, 24]) and reduced synthesis of MMP-9 may lessen atherosclerotic plaque disruption. Hydroxychloroquine’s ability to lower cholesterol and hemoglobin AIC in diabetes may not contribute to benefit with short courses of treatment [25]. However, if ongoing studies show that it offers protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection, then longer courses of drug administration may be recommended. The platelet inhibiting properties of hydroxychloroquine, either alone or in combination with aspirin [26] may be attractive with either short or more prolonged courses of treatment [27].

Chatre et al. [28] performed a systematic review of cardiac complications attributable to hydroxychloroquine (and chloroquine). There were a total of 127 patients from individual case reports and case series. The median duration of treatment was 7 years, with a range from 3 days to 35 years. The cumulative doses were 1000 g or more. The most comment adverse cardiovascular effect was AV conduction abnormalities (85% of patients). Reduced ventricular performance was observed as was heart failure with the former recovering in nearly half of patients after drug withdrawal. It is important to acknowledge that may of the patients included in the systematic review were being treated for autoimmune disease.

Potential risks

The adverse effects associated with taking hydroxychloroquine are similar to those observed with chloroquine and include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, AV conduction defects, a prolonged QTc interval with torsades de pointe ventricular tachycardia, hypokalemia, hypotension and circulatory collapse. The hemodynamic complications are much more likely to occur with excessively large doses; however, QTc prolongation can be seen with standard recommended doses even in the absence of concomitant electrolyte abnormalities (low potassium, magnesium or calcium).

Drug-drug interactions must be considered in patients taking hydroxychloroquine and include digoxin (increased levels), insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents (heighted responses and hypoglycemia), antiepileptic drugs, methotrexate, cyclosporine and drugs that prolong the QTc.

Data supporting the investigation of hydroxychloroquine in Covid-19

The antiviral properties of hydroxychloroquine have been summarized and provide a foundation for additional formative discussion. Yao and colleagues [29] determined the pharmacological activity of hydroxychloroquine employing SARS-CoV-2 infected Vero cells. Pharmacokinetic models were constructed by integrating vitro data. Hydroxychloroquine concentrations in lung fluid were simulated. Hydroxychloroquine (EC50 = 0.72 μM) was found to be more potent than chloroquine (EC50 = 5.47 μM). Based on modeling, a loading dose of 400 mg twice daily of hydroxychloroquine sulfate given orally, followed by a maintenance dose of 200 mg given twice daily for 4 days may be recommended for SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The in vitro cytotoxicity of hydroxychloroquine was determined in VeroE6 cells and showed that the 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) value for HCQ was 249.50 μM [30]. The dose–response was assessed at four different multiplicities of infection (MOIs) by quantification of viral RNA copy numbers in the cell supernatant at 48 h post infection. At each of the MOIs (0.01, 0.02, 0.2, and 0.8), the 50% maximal effective concentration (EC50) for hydroxychloroquine was 4.51, 4.06, 17.31, and 12.96 μM, respectively. The findings were corroborated by immunofluorescence microscopy by assessing different expression levels of virus nucleoprotein at the indicated drug concentrations at 48 h post-infection.

Gautret and colleagues [31] performed a single arm, open-label clinical study over a 2-week period. A total of 20 Covid-19 confirmed patients (6 asymptomatic, 22 upper respiratory tract symptoms and 8 lower respiratory tract symptoms) received hydroxychloroquine 600 mg daily. By day 6, there was decreased viral load carriage in treated patients compared to untreated patients derived from the medical literature. The effects of hydroxychloroquine were reinforced by the addition of azithromycin.

More on the importance of QTc interval prolongation and patient safety

There are patient demographics and characteristics that are associated with a higher likelihood of developing drug-related QTc prolongation (Table 1). All clinicians and prescribing health providers should be familiar with each.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics associated with drug-induced arrhythmias

| Demographics |

| Advanced age |

| Female sex |

| Conditions |

| Heart failure |

| Structural heart disease |

| Ischemic heart disease |

| Prior myocardial infarction |

| Bradycardia |

| Conduction abnormalities |

| Genetic (long QT syndrome) |

| Laboratory abnormalities |

| Hypokalemia |

| Hypomagnesemia |

| Hypocalcemia |

| Renal impairment (drug clearance) |

| Hepatic impairment (drug metabolism) |

The number of drugs that can prolong the QTc is substantial (− 220 known) and typically divided into those with a known risk of QTc prolongation or torsades de pointes ventricular tachycardia, possible risk and conditional risk (i.e. if administered with another QTc prolonging drug; in the setting of hypokalemia or in patients with predisposing conditions such as familial long QT syndrome). (Crediblemeds.org) [32]

In the context of current treatment for COVID-19, including empiric regimens being employed by clinicians as they await the results of clinical trials, azithromycin’s effect on QTc must be recognized and included in the equation. The FDA issued a warning on May 17, 2012 on the risk of potentially fatal heart rhythm abnormalities associated with the drug. Employing a large claims database of over 12 million patients with greater than 23 million azithromycin prescriptions, Patel and colleagues [33] identified nearly 25% of patients were receiving another drug with QTc producing effects. The presence of pre-existing cardiac conditions was ~ 8.0%. Neither concomitant QTc prolonging drugs nor cardiac conditions differed after as compared with before the FDA warning.

The clinical community to include emergency room physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants and pharmacists, as well as others employing a tele-health platform must adopt a well-informed and consistent approach to safely prescribe drugs with QTc prolonging or proarrhythmic potential [34]. A management algorithm must include a comprehensive understanding of drug pharmacology, risk–benefit relationships and a track record of safety. In addition, there must be a thorough evaluation of patient history focusing on conditions known to be associated with arrhythmias, as well as a detailed family history of cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, sudden cardiac death and internal cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) insertion (see Table 1). Last, dose adjustments, monitoring of electrolytes and serial electrocardiograms should be included in the management plan when indicated. Consensus recommendations from the Internal Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) should be followed (www.ich.org).

Vandael et al. [35] developed a risk score for QTc prolongation following treatment with a drug known to have this potential effect. In a majority of patients (25 of 26), the RISQ-PATH score was ≥ 10 (Table 2). The score had a sensitivity of 92.6% (95% CI 78.4–99.8%) and a negative predictive value of 98% (95% CI 88.2–99.9%).

Table 2.

Assessment of patient risk for QTc interval prolongation

| Preliminary RISQ-PATH score | |

|---|---|

| Risk factors | Points |

| Age ≥ 65 years | 3 |

| Female sex | 3 |

| Smoking | 3 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 1 |

| (Ischemic) cardiomyopathy | 3 |

| Hypertension | 3 |

| Arrhythmia | 3 |

| Prolonged QTc (≥ 450(♂)/470(♀) ms) on a baseline ECG | 6 |

| Thyroid disturbances | 3 |

| Liver failure | 1 |

| Neurological disorders | 0.5 |

| Diabetes | 0.5 |

| Potassium ≤ 3.5 mmol/L | 6 |

| Calcium < 2.15 mmol/L | 3 |

| CRP > 5 mg/L | 1 |

| Estimated glomular filtration rate ≤ 30 ml/min | 0.5 |

| For each list 1 QT-drug CredibleMedsa | 3 per drug |

| For each list 2 QT-drug CredibleMedsa | 0.5 per drug |

| For each list 3 QT-drug CredibleMedsa | 0.25 per drug |

| Total | Maximum 40.5 points + sum QT-drugs |

BMI body mass index, QT-drug QTc-prolonging drug

aIncluding the new QTc-prolonging drug that is started

From: Development of a risk score for QTc-prolongation: the RISQ-PATH study [32]

The Brazilian study of chloroquine underscores the importance of cardiovascular safety when using or studying antimalarial drugs [36]. The study included 81 hospitalized Covid-19 confirmed patients of whom approximately half received 450 mg chloroquine twice daily for five days and the remainder received 600 mg twice daily for 10 days. The CloroCovid-19 study was performed on a background of treatment with azithromycin and ceftriaxone. Arrhythmias were observed within three days of study initiation and by six days 11 patients had died. There was a greater likelihood of having a QTc interval > 500 ms (25%) in patients receiving high-dose chloroquine. Accordingly, this arm of the study was terminated. While more detailed information is needed, high-dose chloroquine may not be safe in the treatment of Covid-19. The safety of lower doses must be established in Covid-19.

It is vital to educate the lay community about the potential risks associated with non-medicinal chloroquine products. Similarly, patients with Covid-19 for whom a clinician believes that either chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine is indicated must receive information, preferably in the form of a fact sheet that clearly summarized the dose, duration of treatment, potential risks, side-effects and drug-drug interactions.

Planned and ongoing clinical trials that include chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine

The number of clinical trials in Covid-19 patients, either planned or ongoing is increasing on a daily basis. The reader is referred to clinicaltrial.gov for regular updates.

Adopting an optimal approach to conducting clinical trials in global health emergencies

The World Health Organization (WHO) working with the Global Research Collaborative for Infectious Disease Preparedness (GLOPID-R) established a Covid-19 research roadmap (www.glopid-r.org) in January 2020. The design is tailored for a global research response that embraces cross-border collaborations and partnerships across professional disciplines worldwide. A major focus of GLOPID-R is data sharing based on filling knowledge gaps, establishing research priorities and accelerating the generation of scientific information required to address the Covid-19 pandemic.

An initial evaluation by the WHO called for priority to embark upon global research built on common platforms for standardized processes, protocols and tools. It also emphasized several knowledge gaps about SARS-CoV-2 to include compartments of replication, the prognostic importance of viral load, immune-biomarkers, genotype–phenotype relationships, genotype drifts that might impact diagnostic assays and technical limitations for serologic assay development (simple immunofluorescence assay [IFA], differential IFA, enzyme linked immunoabsorbance assay [ELISA] and neutralization assays).

The group exhibited substantial foresight and raised questions about the development of point-of-care testing, the identification of prognostic markers and digital solutions for field laboratory needs. They also emphasized the importance of ethical considerations as being crucial to governance, transparency, accountability, equity and trust. Last, the group underscored the importance of establishing a framework for social science research, global social science researchers and understanding social and behavioral dynamics during the Covid-19 pandemic (Table 3).

Table 3.

Eight immediate research actions for Covid-19

| 1. Mobilize research on rapid point of care diagnostics for use at the community level—this is critical to be able to quickly identify sick people, treat them and better estimate how widely the virus has spread |

| 2. Immediately assess available data to learn what standard of care approaches from China and elsewhere are the most effective—there is an imperative to optimize standard of care given to patients at different stages of the disease and take advantages of all available technological innovations to improve survival and recovery |

| 3. Evaluate as fast as possible the effect of adjunctive and supportive therapies—The global research community need to understand what other adjunctive treatments than currently being used are at our disposal that may help with the standard of care provided to patients, including the quick evaluation of interventions such as steroids and high flow oxygen |

| 4. Optimize use of protective equipment and other infection prevention and control measures in health care and community settings—It is critical to protect health care workers and the community from transmission and create a safe working environment |

| 5. Review all evidence available to identify animal host(s), to prevent continued spill over and to better understand the virus transmissibility in different contexts over time, the severity of disease and who is more susceptible to infection—Understanding transmission dynamics would help us appreciate the full spectrum of the disease, in terms of at risk groups, and conditions that make the disease more severe as well as the effectiveness of certain public health interventions |

| 6. Accelerate the evaluation of investigational therapeutics and vaccines by using “Master Protocols”—Rapidly developing master protocols for clinical trials will accelerate the potential to assess what works and what does not, improve collaboration and comparison across different studies, streamline ethics review and optimize the evaluation of new investigational drugs, vaccines and diagnostics |

| 7. Maintain a high degree of communication and interaction among funders so that critical research is implemented—Funders reiterated their current financial commitments to tackling this outbreak and agreed that the priorities agreed at the Forum would help to coordinate existing investments and inform mobilization of additional resources in the coming days, weeks and months |

| 8. Broadly and rapidly share virus materials, clinical samples and data for immediate public health purposes—It was agreed that virus materials, clinical samples and associated data should be rapidly shared for immediate public health purposes and that fair and equitable access to any medical products or innovations that are developed using the materials must be part of such sharing |

Adapted from the: COVID-19 Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC); Global Health and Innovation Forum. February 2020 (www.who.int)

The medical and scientific community’s collective response to the Covid-19 pandemic is predicated on obtaining the best available evidence from prevention, treatment and overall management. The evidence will come from well-designed and conducted clinical trials. It is particularly important in the context of current events to employ a framework that can be applied and adapted to environments and conditions, maintain operational rigor and interpret the results according to the data. While all investigators strive to answer complex questions about Covid-19 and make major contributions, reporting and publishing negative trials are equally, and not infrequently, more important than positive trials.

The R & D Blueprint working group has advocated for the use of “core protocols” when designing clinical trials during public health emergencies like Covid-19 [37, 38]. In addition to providing a strong research platform in the midst of highly dynamic settings encountered during public health emergencies, core or master protocols, inclusion of independent monitoring committees, “pause or stopping” rules, publication metric requirements and clear ground rules for public messaging are needed [38].

Among the many attractive features of core protocols, their inherent design is collaborative in nature, engaging investigators and stakeholders early in the public health emergency to determine the most important research question(s), optimal study design, ethic and regulatory needs, funding sources, country health authority and governmental integration, communications, data security, oversight and clinical operations.

Research quality framework: the key to scientific integrity and patient translatability

An ability to conduct high quality research that is valuable and worthy of serious consideration by the scientific community requires a research quality framework (RQF). While experienced investigators have been using RQF’s for many years, a reminder of its vital role and component parts is fitting given the Covid-19 pandemic and desire for study results to emerge as rapidly as possible. The key processes, metrics and tenets of a RQF are as follows:

Data provenance (internal and external reproducible of the findings)

Quantitative expertise (applied under proper standards to the design, conduct analysis and presentation of the results)

Governance and oversight

Special review of potential conflicts of interests

Comprehensive vetting, implementation and assessment of research practices based on instrumental, research network or organizational standards

Transparency of processes.

Concluding thoughts and future directions

The Covid-19 pandemic has touched everyone on Earth in many ways. Its scope and impact on health, well-being, economic stability and daily life is tragic, heart-breaking and quite personal. Despite an honest and natural human response to a clear threat, this is not a time for reactions; this is not a time for assumptions; this is not a time for desperate measures; this is not a time for guessing what might be a safe and effective treatment. This is a time for facts, measured steps, thoughtful responses and collaborations without borders. This is without question a time to follow the scientific evidence.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Morens DM, Daszak P, Taubenberger JK. Escaping Pandora's box— another novel Coronavirus. N Eng J Med. 2020;382:1293–1295. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2002106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Z, McGoogan JM (2020) Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Kupferschmidt K, Cohen J. Race to find COVID-19 treatments accelerates. Science (New York, NY) 2020;367:1412–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.367.6485.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jakhar D, Kaur I (2020) Potential of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19 causes fears of shortages among people with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Med [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Plowe CV. Antimalarial drug resistance in Africa: strategies for monitoring and deterrence. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;295:55–79. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29088-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savarino A, Boelaert JR, Cassone A, Majori G, Cauda R. Effects of chloroquine on viral infections: an old drug against today's diseases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:722–727. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00806-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boone BA, Murthy P, Miller-Ocuin J, Doerfler WR, Ellis JT, Liang X, Ross MA, Wallace CT, Sperry JL, Lotze MT, Neal MD, Zeh HJ., 3rd Chloroquine reduces hypercoagulability in pancreatic cancer through inhibition of neutrophil extracellular traps. BMC cancer. 2018;18:678. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4584-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Q, Tsuji-Hosokawa A, Willson C, Watanabe M, Si R, Lai N, Wang Z, Yuan JX, Wang J, Makino A. Chloroquine differentially modulates coronary vasodilation in control and diabetic mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:314–327. doi: 10.1111/bph.14864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan X, Xiao YC, Zhang GP, Hou N, Wu XQ, Chen WL, Luo JD, Zhang GS. Chloroquine improves left ventricle diastolic function in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2016;10:2729–2737. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S111253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ben-Zvi I, Kivity S, Langevitz P, Shoenfeld Y. Hydroxychloroquine: from malaria to autoimmunity. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012;42:145–153. doi: 10.1007/s12016-010-8243-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blignaut M, Espach Y, van Vuuren M, Dhanabalan K, Huisamen B. Revisiting the cardiotoxic effect of chloroquine. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2019;33:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10557-018-06847-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keyaerts E, Vijgen L, Maes P, Neyts J, Ranst MV. In vitro inhibition of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus by chloroquine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;323:264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keyaerts E, Li S, Vijgen L, Rysman E, Verbeeck J, Van Ranst M, Maes P. Antiviral activity of chloroquine against human Coronavirus OC43 infection in newborn mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3416–3421. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01509-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, Yang X, Liu J, Xu M, Shi Z, Hu Z, Zhong W, Xiao G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang M, Tang T, Pang P, Li M, Ma R, Lu J, Shu J, You Y, Chen B, Liang J, Hong Z, Chen H, Kong L, Qin D, Pei D, Xia J, Jiang S and Shan H (2020) Treating COVID-19 with chloroquine. J Mol Cell Biol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Al-Bari MA. Chloroquine analogues in drug discovery: new directions of uses, mechanisms of actions and toxic manifestations from malaria to multifarious diseases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:1608–1621. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Plantone D, Koudriavtseva T. Current and future use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in infectious, immune, neoplastic, and neurological diseases: a mini-review. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38:653–671. doi: 10.1007/s40261-018-0656-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohkuma S, Poole B. Fluorescence probe measurement of the intralysosomal pH in living cells and the perturbation of pH by various agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3327–3331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sperber K, Quraishi H, Kalb TH, Panja A, Stecher V, Mayer L. Selective regulation of cytokine secretion by hydroxychloroquine: inhibition of interleukin 1 alpha (IL-1-alpha) and IL-6 in human monocytes and T cells. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:803–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldman FD, Gilman AL, Hollenback C, Kato RM, Premack BA, Rawlings DJ. Hydroxychloroquine inhibits calcium signals in T cells: a new mechanism to explain its immunomodulatory properties. Blood. 2000;95:3460–3466. doi: 10.1182/blood.V95.11.3460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fantini J, Scala CD, Chahinian H and Yahi N (2020) Structural and molecular modeling studies reveal a new mechanism of action of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents 105960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Jacobsson LT, Turesson C, Gulfe A, Kapetanovic MC, Petersson IF, Saxne T, Geborek P. Treatment with tumor necrosis factor blockers is associated with a lower incidence of first cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1213–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali M, Girgis S, Hassan A, Rudick S, Becker RC. Inflammation and coronary artery disease: from pathophysiology to Canakinumab anti-inflammatory thrombosis outcomes study (CANTOS) Coron Artery Dis. 2018;29:429–437. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newby AC. Metalloproteinases promote plaque rupture and myocardial infarction: a persuasive concept waiting for clinical translation. Matrix Biol. 2015;44–46:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallace DJ, Metzger AL, Stecher VJ, Turnbull BA, Kern PA. Cholesterol-lowering effect of hydroxychloroquine in patients with rheumatic disease: reversal of deleterious effects of steroids on lipids. Am J Med. 1990;89:322–326. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90345-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Achuthan S, Ahluwalia J, Shafiq N, Bhalla A, Pareek A, Chandurkar N, Malhotra S. Hydroxychloroquine's efficacy as an antiplatelet agent study in healthy volunteers: a proof of concept study. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2015;20:174–180. doi: 10.1177/1074248414546324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung H, Bobba R, Su J, Shariati-Sarabi Z, Gladman DD, Urowitz M, Lou W, Fortin PR. The protective effect of antimalarial drugs on thrombovascular events in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:863–868. doi: 10.1002/art.27289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chatre C, Roubille F, Vernhet H, Jorgensen C, Pers YM. Cardiac complications attributed to chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine: a systematic review of the literature. Drug Saf. 2018;41:919–931. doi: 10.1007/s40264-018-0689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao X, Ye F, Zhang M, Cui C, Huang B, Niu P, Liu X, Zhao L, Dong E, Song C, Zhan S, Lu R, Li H, Tan W and Liu D (2020) In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing design of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Clin Infect Dis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Liu J, Cao R, Xu M, Wang X, Zhang H, Hu H, Li Y, Hu Z, Zhong W, Wang M. Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020;6:16. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, Hoang VT, Meddeb L, Mailhe M, Doudier B, Courjon J, Giordanengo V, Vieira VE, Dupont HT, Honore S, Colson P, Chabriere E, La Scola B, Rolain JM, Brouqui P and Raoult D (2020) Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 32.Woosley RL, Black K, Heise CW, Romero K. CredibleMeds.org: What does it offer? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018;28:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunker A, Kolanczyk DM, Maendel CM, Patel AR, Pettit NN. Impact of the FDA Warning for Azithromycin and Risk for QT Prolongation on Utilization at an Academic Medical Center. Hosp Pharmacy. 2016;51:830–833. doi: 10.1310/hpj5110-830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thind M, Rodriguez I, Kosari S, Turner JR. How to prescribe drugs with an identified proarrhythmic liability. J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;60:284–294. doi: 10.1002/jcph.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vandael E, Vandenberk B, Vandenberghe J, Spriet I, Willems R, Foulon V. Development of a risk score for QTc-prolongation: the RISQ-PATH study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39:424–432. doi: 10.1007/s11096-017-0446-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borba M, Val FdA, Sampaio VS, Alexandre MA, Melo GC, Brito M, Mourao M, Brito Sousa JD, Baia-da-Silva d, Guerra MVF, Hajjar L, Pinto RC, Balieiro A, Naveca FG, Xavier M, Salomao A, Siqueira A, Schwarzbolt A, Croda JHR, Nogueira ML, Romero G, Bassat Q, Fontes CJ, Albuquerque B, Daniel-Ribeiro C, Monteiro W and Lacerda M (2020) Chloroquine diphosphate in two different dosages as adjunctive therapy of hospitalized patients with severe respiratory syndrome in the context of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) infection: Preliminary safety results of a randomized, double-blinded, phase IIb clinical trial (CloroCovid-19 Study). medRxiv. 2020.04.07.20056424.

- 37.Kieny MP, Salama P. WHO R&D Blueprint: a global coordination mechanism for R&D preparedness. Lancet. 2017;389:2469–2470. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31635-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woodcock J, LaVange LM. Master protocols to study multiple therapies, multiple diseases, or both. N Eng J Med. 2017;377:62–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1510062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]