Editor—In the USA and around the world, the surge of patients with respiratory failure as a result of the pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has overwhelmed healthcare systems. The need for ventilators in many hospitals in the USA may soon exceed the supply.1 In the scenario of an inadequate supply of ventilators, healthcare systems may choose to implement ethical ventilator allocation schemes1 or devise alternative treatment methods to support patients in respiratory failure as a result of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). One such alternative is to use a single ventilator to provide mechanical ventilation to two or more patients. Although this method was tested with artificial lungs2 and in sheep,3 and briefly utilised successfully in a mass casualty event,4 there are no outcome data for ventilator sharing amongst patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Recently, the Assistant Secretary for Health and the US Surgeon General released a letter5 tacitly approving the decision to use shared ventilation at ‘the individual institution, care provider, and patient level’ despite a joint statement of several major medical societies, including the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), explicitly advising against its use.6

The decision to implement shared ventilation is ethically fraught because it necessarily deprives one patient of standard-of-care treatment to potentially save another patient's life. To justify this risk, shared ventilation must confer a survival benefit to a population of patients compared with utilising an ethical ventilator allocation scheme and pursuing alternative respiratory support measures for patients not receiving ventilator treatment. However, without scientific investigation of shared ventilation in a representative population of patients with COVID-19, it is impossible to know how patients will fare. If the mortality rate of sharing ventilators increases compared with standard-of-care ventilation, more patients could die despite expanded treatment capacity.

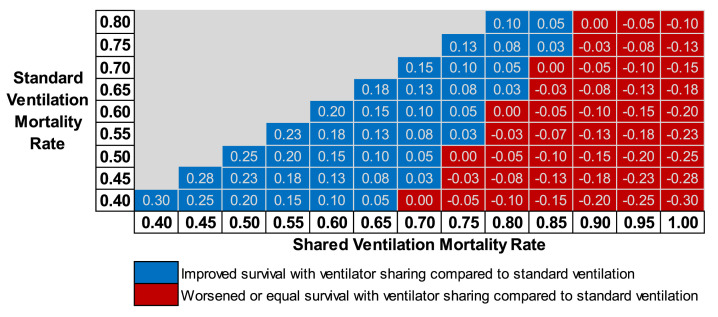

The following conceptual framework helps to assess the impact on survival of shared ventilation. Consider a hospital that needs to treat 200 patients in respiratory failure, but has only 100 ventilators. If we assume that all patients who do not receive a ventilator die and the mortality rate for patients receiving standard ventilation is 50%, then 50 of the 200 patients will survive. With ventilator sharing for all 200 patients, 100 patients will survive if the mortality rate is the same. However, in a shared ventilation strategy, it would be impossible to individualise the adjustment of certain key parameters, such as tidal volume and PEEP, to limit ventilator-induced lung injury.2 , 6 Thus, the mortality rate of patients receiving shared ventilation is likely to exceed the mortality rate of standard ventilation. If the mortality rate of shared ventilation is 75%, then only 50 of the 200 patients will survive, and there will be no benefit. In this example, the degree to which the mortality rate of shared ventilation is below or above 75% will determine the extent to which patients are saved or harmed by this strategy compared with the standard of care with ventilator allocation.

Although limited, this simplified algebraic framework raises several key points. First, it is critical to compare the morality rates of shared and standard ventilation to determine the overall effectiveness or harm (Fig 1 ). If practitioners knew the mortality rate of mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19, then this analysis would provide an estimate for the tolerable increase in mortality with shared ventilation that would still achieve net benefit. Furthermore, it highlights that the overall benefit of shared ventilation is diminished with higher mortality rates of COVID-19 in standard-of-care treatment. In subpopulations with higher mortality, such as severe ARDS with multi-organ failure, shared ventilation is unlikely to yield a substantial survival benefit. This conceptual framework, moreover, does not take into account important considerations with shared ventilation, such as the logistical burden of its implementation or risk to healthcare workers from multiple circuit disconnects as two patients are connected to a single ventilator or placed back to their own ventilators.

Fig 1.

Comparing survival differences with shared or standard ventilation by their hypothetical mortality rates. The numbers within each cell represent the proportional change in survival with shared ventilation for a population of patients comparing the shown mortality rates. Four key assumptions are made in this analysis: (i) the shared ventilation strategy doubles treatment capacity (a condition that is unlikely to be met in practice), (ii) all patients receive either shared ventilation or standard ventilation, (iii) all patients not receiving ventilator treatment will die, and (iv) the mortality rate of shared ventilation will not be less than standard ventilation.

Increasing the survival rate is the singular priority of practitioners providing care to critically ill patients during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in the face of ventilator scarcity. However, as Fig 1 demonstrates, the overall mortality with shared ventilation may exceed ventilator allocation with standard-of-care treatment. It is important for practitioners to acknowledge that shared ventilation is an unproved medical treatment that may cause more harm than good, and its benefit should be demonstrated in a scientific and ethical manner. Physicians of any hospital proceeding with shared ventilation should, at a minimum, (i) obtain informed consent that acknowledges its unproved benefit, (ii) offer non-invasive respiratory therapies or palliative treatments as an alternative, (iii) diligently record and analyse outcomes before and after implementation of shared ventilation, (iv) expeditiously disseminate the conclusions of their analysis publicly, and (v) develop an ethical protocol to discontinue shared ventilation if pre-specified evaluations show harm. It is incumbent upon the first practitioners offering shared ventilation to demonstrate its benefit. Without undertaking such measures, implementation of shared ventilation diminishes the ethical and scientific basis of our care and risks an increased rate of death in the patients we are desperately trying to save.

Declaration of interest

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Emanuel E.J., Persad G., Upshur R. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Branson R.D., Blakeman T.C., Robinson B.R., Johannigman J.A. Use of a single ventilator to support 4 patients: laboratory evaluation of a limited concept. Respir Care. 2012;57:399–403. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paladino L., Silverberg M., Charchaflieh J.G. Increasing ventilator surge capacity in disasters: ventilation of four adult-human-sized sheep on a single ventilator with a modified circuit. Resuscitation. 2008;77:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menes K., Tintinalli J., Plaster L. How one Las Vegas ED saved hundreds of lives after the worst mass shooting in U.S. history. Emerg Physicians Monthly. 2017 https://epmonthly.com/article/not-heroes-wear-capes-one-las-vegas-ed-saved-hundreds-lives-worst-mass-shooting-u-s-history/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps . 2020. Optimizing ventilator use during the COVID-19 pandemic.https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/optimizing-ventilator-use-during-covid19-pandemic.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joint statement on multiple patients per ventilator. 2020. https://www.asahq.org/about-asa/newsroom/news-releases/2020/03/joint-statement-on-multiple-patients-per-ventilator Available from: [Google Scholar]