To the Editor,

SARS-CoV-2 infection in children has been described in around 1% of cases in China.1 Although data are still limited, most series report mostly mild cases, even in infants. Critically-ill patients represent 0.6% of children and 50% of them are younger than 1 year old.2 There have been very few reports of deaths. In a Wuhan series, a 10-month-old infant with intussusception developed multiorgan failure and died, while 3 patients had underlying diseases, representing 1.7% of children.3

Spain is currently in a situation of intense community transmission with more than 100 000 reported cases.

Between 11 and 18 March 2020, 12 children with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection were admitted to a large university hospital, 5 (41.6%) of whom had underlying disease (1 liver transplant, 1 vasculitis with hemodialysis, 2 congenital heart disease, and 1 Hurler syndrome with associated dilated cardiomyopathy).

One of the 12 children was a 5-month-old boy who had been diagnosed with heart failure and mucopolysaccharidosis type I-Hurler syndrome at age 1 month. He had moderate dilatation of the left ventricle assessed by echocardiography and computed tomography (figure 1 ), left ventricular end diastolic diameter 30 mm Z + 3.8, and moderate left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction 48%). Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with human recombinant αL-iduronidase was started on a weekly basis after neurologist and hematologist consultation as a bridge to bone marrow transplant. After 7 weeks, his function deteriorated, with increased left ventricular volume (left ventricular end diastolic diameter 48 mm Z + 8.5) lower ejection fraction (EF; < 30%) moderate mitral regurgitation, and left atrium enlargement. The patient required admission to intensive care with adrenaline and milrinone drips. A computed tomography scan was performed to rule out coronary artery lesions. The possibility of heart transplant listing was excluded. After intense heart failure therapy, iv drips were discontinued and the patient was switched to oral therapy with captopril, diuretics, carvedilol and digoxin with a mild improvement, which allowed discharge after 8 weeks. ERT was continued to allow bone marrow transplant if cardiac function improved.

Figure 1.

Retrospective electrocardiogram-triggered 320-multidetector cardiac computed tomography angiography image showing marked dilation of the left ventricle.

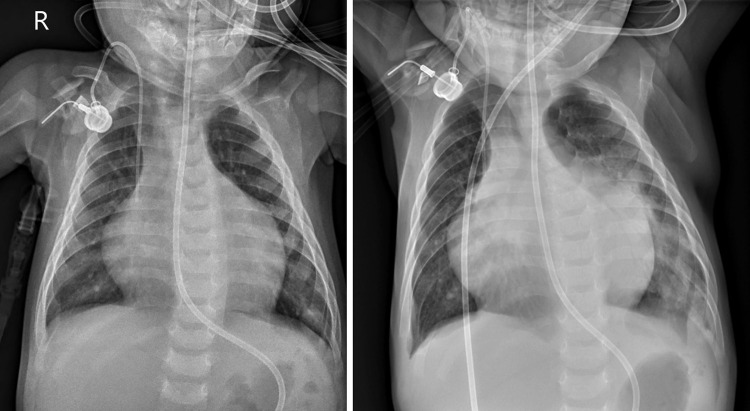

When the patient was 5 months old, he was hospitalized after a 24-hour course of irritability, low-grade fever (below 38 C), cough, runny nose, and vomiting. He showed pallor, slight respiratory distress, and bibasal pulmonary subcrackles. Chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly without consolidations (figure 2A ). An electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm at 160 bpm and biventricular hypertrophy. The last echocardiogram performed 2 weeks before admission showed left ventricular dilation with left ventricular end diastolic diameter 39 mm Z + 7.3 EF 30%, and longitudinal global strain − 10%. Leukocyte count was 21 400/mm3 with 12 890/mm3 neutrophils, and C-reactive protein 36 mg/L. Treatment was started with fluid restriction and conventional oxygen therapy (1-2 LPM).

Figure 2.

A: Chest film taken on hospital admission showing an abnormal (wide) cardiothoracic ratio, without visible lung abnormalities. R, right. B: follow-up radiograph obtained at day 3 after admission showing bilateral perihilar consolidation with air bronchograms, extending to left lung base, even in retrocardiac space.

COVID-19 disease was suspected and SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction was positive. Captopril was withdrawn in the emergency room prior to confirmation of the diagnosis. At 24 hours after admission, the patient was stable without oxygen therapy. After 48 hours, there was an increase in bilateral pulmonary crackles and palpebral edema. He had low-grade fever without analytical impairment, so it was interpreted as worsening heart failure with good response to diuretic treatment. However, 72 hours after admission, he had high fever (39.6 C) and respiratory distress, and chest X-ray revealed extensive symmetric parahilar consolidations that extended to the paracardiac region and pulmonary base on the left side (figure 2B). Blood testing showed no lymphopenia (2540/μL), C-reactive protein 244 mg/L, and D-dimer 973 ng/mL. Blood culture was negative. Hydroxychloroquine and ceftriaxone were prescribed, and remdesivir requested, but 2 hours later the patient had a cardiac arrest, requiring intubation. After admission to the pediatric intensive care unit, he had a second cardiac arrest, which proved fatal.

This report emphasizes the fatal clinical course of an infant admitted with SARS-CoV-2 infection associated with significant comorbidity. In the current COVID-19 outbreak, most deaths occur in elderly patients with or without comorbidities.1 Cardiac injury is a common condition among hospitalized adult patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, and has been associated with a higher risk of in-hospital mortality.4 The outcomes of infants with severe heart disease associated with SARS-CoV-2 infections have not been reported.

Mucopolysaccharidosis type I-Hurler syndrome is a lysosomal storage disease caused by a deficiency of the lysosomal enzyme α-L-iduronidase. The clinical course is characterized by progressive multisystem morbidity with cardiovascular deterioration and death in infancy. Current treatment includes ERT and bone marrow transplant.5 Severe cardiomyopathy in early infancy may complicate the clinical situation and affect survival but ERT has been reported to improve cardiac function.5

SARS-CoV-2 infection is proposed to evolve in 3 phases, causing mortality in the third phase after about 2 weeks or more.6 In the early phase, SARS-CoV-2 multiplies in the host, primarily focusing on the respiratory system with mild symptoms. SARS-CoV-2 binds to its target using the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor on human cells, abundantly present in the human lung. During the second phase, lung involvement is established, and lymphopenia appears. A minority of patients will reach the third phase of systemic hyperinflammation with an increase in inflammatory cytokines, interleukins, C-reactive protein, ferritin, D-dimer, and others. Troponin and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide can also be elevated.

The clinical course of our patient was very short, reaching the hyperinflammation phase in just 3 to 4 days from the onset of symptoms. The situation of previous heart failure could undoubtedly contribute to a low reserve that led to cardiac arrest. The role of previous treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor may have contributed to his rapid deterioration but the role of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors remains to be elucidated.

There is scarce information about SARS-CoV-2 infection in children with underlying disease. It is noteworthy that in the first week of the pandemic in our center, 5 of the 12 admitted children had significant comorbidities. Patients with heart failure due to cardiomyopathies or congenital heart disease may constitute a group of special concern.

.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr Samuel Ignacio Pascual for his advice (Pediatric Neurology Department).

References

- 1.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong Y., Mo X., Hu Y. Epidemiological Characteristics of 2143 Pediatric Patients With 2019 Coronavirus Disease in China. Pediatrics. 2020 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Z., Xiong H., Li J.X. COVID-19 With Post-Chemotherapy Agranulocytosis in Childhood Acute Leukemia: A Case Report. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E004. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2020.0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi S., Qin M.M., Shen B.B. Association of Cardiac Injury With Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in Wuhan. China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020:e200950. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiseman D.H., Mercer J., Tylee K. Management of mucopolysaccharidosis type IH (Hurler's syndrome) presenting in infancy with severe dilated cardiomyopathy: a single institution's experience. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36:263–270. doi: 10.1007/s10545-012-9500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siddiqi H.K., Mehra M.R. COVID-19 Illness in Native and Immunosuppressed States: A Clinical-Therapeutic Staging Proposal. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]