To the Editor,

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is the clinical manifestation of infection by severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Patients with this condition usually present with respiratory symptoms that can progress to pneumonia, and severe cases may develop acute respiratory distress syndrome and cardiogenic shock. Information on the etiology and mortality of cardiogenic shock in COVID-19 is currently limited and is the objective of the present study.

Between 1 March and 15 April, 2020, urgent cardiac catheterization was carried out in 23 patients with a suspected ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome or cardiorespiratory arrest. Seven of them (30%) tested positive for COVID-19 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in nasopharyngeal exudate. All patients testing negative for COVID-19 were ultimately discharged without complications. Of the 7 testing positive for COVID-19, 2 were discharged, 1 died due to respiratory failure secondary to severe pneumonia, and 4 developed cardiogenic shock immediately after arrival at the hospital. Three of these 4 patients died, yielding a mortality rate of 75% in the context of cardiogenic shock. The clinical, analytical, and imaging features of these patients, the treatment they received, and their clinical courses are summarized in table 1 .

Table 1.

Clinical, analytical, and imaging features, treatment, and outcome of 4 patients with cardiogenic shock complications

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Woman | Man | Man | Woman |

| Age, y | 42 | 50 | 75 | 37 |

| Weight, kg/BMI | 50/19.5 | 66/21.7 | 65/22.9 | 120/43 |

| CVRF | Dyslipidemia | None | None | Morbid obesity |

| Chronic treatment | Drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol 3/0.02 mg (oral contraceptive) | None | None | None |

| Comorbidities | None | Copper metabolism disorder of unknown origin Benign right mediastinal tumor |

None | History of DVT 8 years previously due to immobilization after a fracture |

| Symptom onset to emergency room admission, d | 12 | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| Symptoms | Dyspnea, diarrhea, vomiting, anosmia, and dysgeusia | Fever, dyspnea, and cough | Dyspnea | Fever, dyspnea and chest pain |

| ECG | Sinus rhythm with recent-onset LBBB | Sinus tachycardia with lateral ST segment elevation, 2 mm | Complete atrioventricular block with inferior ST segment elevation | Sinus tachycardia SI QIII TIII pattern Inconclusive anterior ST segment elevation |

| Chest radiography | Cardiomegaly. Diffuse bilateral infiltrates | Extensive bilateral lung involvement: faint patchy opacities in the right lung and faint, diffusely increased density of the left lung, predominantly in the middle fields No cardiomegaly | Bilateral parenchymal opacities No cardiomegaly |

Increased peripheral density in the right lung base obliterating the costophrenic angle, consistent with peripheral lung consolidation |

| Echocardiography | LV dilation with severely reduced LVEF and global hypokinesis No pericardial effusion |

No LV dilation, akinesis of all basal segments and hypercontractility of mid-apical segments Normal right chambers No pericardial effusion |

No LV dilation, inferior basal akinesis with moderate dysfunction Severe RV dilation with severe dysfunction No pericardial effusion |

Not done |

| Catheterization | Coronary arteries normal Pulmonary arteries normal |

Coronary arteries normal Ventriculography shows an inverted takotsubo pattern |

Thrombotic occlusion of middle segment of the right coronary artery | No time to perform catheterization |

| Troponin I, ng/mL | 70.4 (NV < 0.1) | 64.1 | 500 | 0.4 |

| BNP, pg/mL | Not available | 790.7 | 2212.4 | 382 |

| IL-6, pg/mL | Not available | 260.2 | Not available | 50.93 |

| D dimer, ng/mL | 4342 (NV < 500) | 2442 | 7530 | 3128 |

| CRP, mg/L | 1 | 379.5 | 113.8 | 82.9 |

| Lymphocytes, 103/L | 8.04 | 0.80 | 0.90 | 1.91 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 8 | 15.6 | 21.2 | 13.7 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | Not available | 986.67 (NV 20-300) | Not available | 232 |

| Presumptive cardiologic diagnosis | Fulminant myocarditis | Stress cardiomyopathy Inverted takotsubo |

Inferior infarction, Killip III | High-risk bilateral PTE |

| Treatment for COVID-19 | No time to establish treatment | Hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/12 h Lopinavir-ritonavir 200/50 mg, 2 tablets/12 h Tocilizumab 400 mg/day Azithromycin 500 mg/day Methylprednisolone 30 mg/day (tapering dose) |

Since positive test results for COVID-19, no time to establish treatment | Since positive test results for COVID-19, no time to establish treatment |

| Anticoagulant /antiplatelet therapy | NFH | No | Aspirin 300 mg and ticagrelor 180 mg* Tirofiban i.v. |

Enoxaparin 120 mg/12 h Fibrinolysis with i.v. tPA |

| Clinical course | Cardiorespiratory arrest CPR maneuvers Arrhythmic storm Refractory VF Cardiogenic shock VA-ECMO and IABC Mechanical ventilation Death |

Mixed shock (initially cardiogenic and later septic) Mechanical ventilation Vasoactive support (3 days) Discharged home at 11 days Normalization of contractility changes |

Cardiorespiratory arrest Primary VF Primary PCI Cardiogenic shock refractory to vasoactive amines Mechanical ventilation Multiorgan failure Death |

Cardiogenic shock Cardiorespiratory arrest and electromechanical disassociation Died following CPR maneuvers |

BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CRP, C-reactive protein; CVRF, cardiovascular risk factors; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; IABC, intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation; i.v., intravenous; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LV, left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NFH, non-fractionated heparin; NV, normal values; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PTE, pulmonary thromboembolism; RV, right ventricle; tPA, tissue plasminogen activator; VA-ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; VF, ventricular fibrillation;

Ticagrelor was administered despite knowledge of potential interactions with lopinavir-ritonavir. COID-19 was diagnosed after the primary PCI.

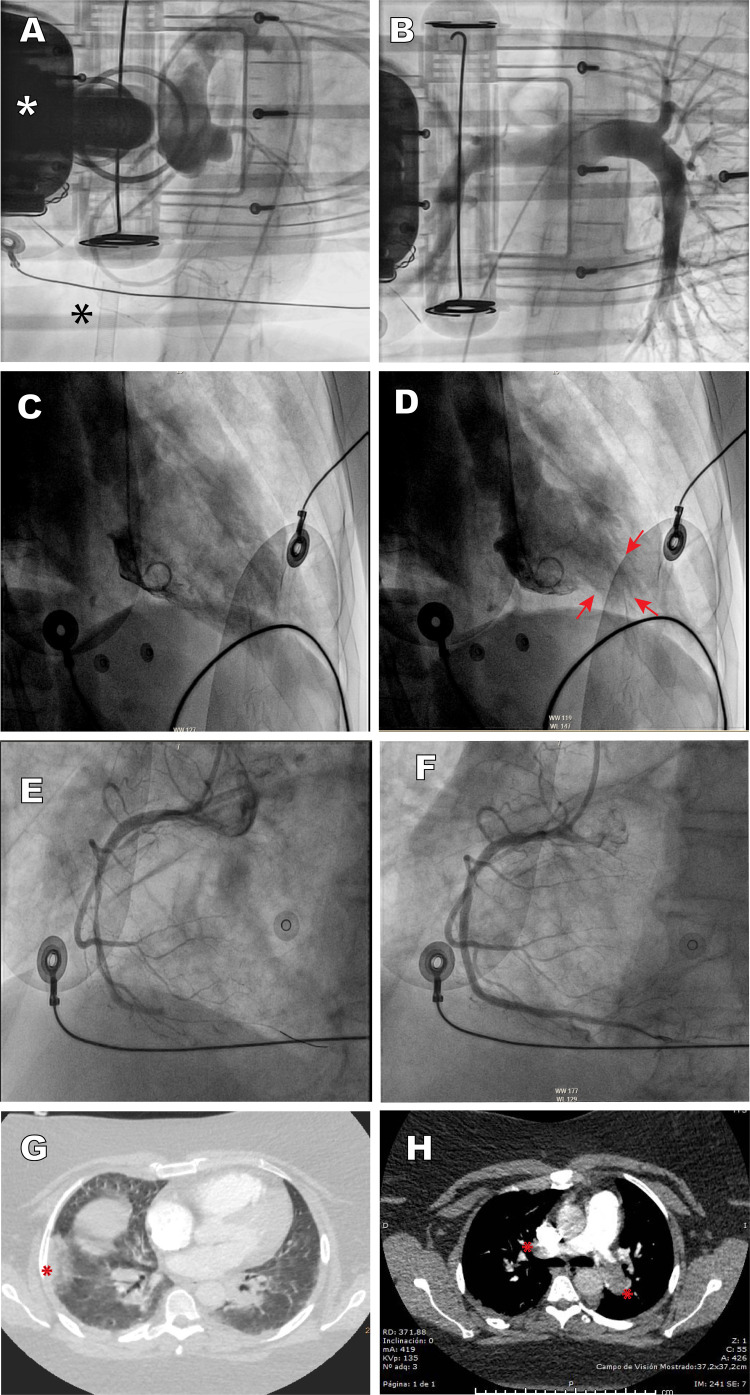

The first case was a 42-year-old woman, with no cardiovascular risk factors or comorbidities, who attended the emergency room with symptoms of dyspnea and cough. Minutes later she developed cardiorespiratory arrest in a defibrillation-amenable rhythm, which led to an arrhythmic storm refractory to antiarrhythmic therapy. Echocardiography showed severe biventricular dysfunction. During cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the cardiac catheterization laboratory, a venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) support system was implanted by peripheral cannulation. Aortography depicted a normal aorta and coronary arteries, and pulmonary angiography ruled out pulmonary thromboembolism (figure 1A,B ). At completion of the procedure, an intra-aortic counterpulsation balloon was implanted to attempt left ventricular unloading, as well as a temporary pacemaker, but the patient died within hours in refractory shock. As the patient tested PCR-positive for COVID-19, the most likely diagnosis was acute fulminant myocarditis.

Figure 1.

A: case 1, aortography depicts a normal aorta and coronary arteries; the white asterisk indicates the chest compression device, and the black asterisk the venous cannula of the extracorporeal membrane oxygenator. B: case 1, pulmonary angiography shows normal findings. C and D: case 2, ventriculography depicts a pattern consistent with inverted tako-tsubo, diastole and systole; the arrows indicate apical hypercontractility. E and F: case 3, thrombotic occlusion of the mid segment of the right coronary artery and revascularization with stent implantation. G: case 4, CT angiography depicts pulmonary infarction (asterisk) and patchy peripheral opacities consistent with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. H: case 4, CT angiography shows thrombotic occlusion of both pulmonary arteries (asterisks). This figure is shown in full color only in the electronic version of the article.

The second case was a 50-year-old man with no cardiovascular risk factors or comorbid conditions, who was hospitalized for severe bilateral pneumonia due to COVID-19 with a need for mechanical ventilation. A few hours after he was admitted, he suddenly developed severe hypotension (systolic blood pressure, 60 mmHg) with lateral wall ST-segment elevation. Urgent cardiac catheterization showed lesion-free coronary arteries and severe left ventricular dysfunction with contractility changes consistent with stress cardiomyopathy (inverted tako-tsubo), with akinesis of the basal and mid segments, and apical hypercontractility (figure 1C,D). Left ventricular end-diastolic pressure was 22 mmHg. The patient progressed gradually to distributive shock, requiring ventilation. After 11 days of hospitalization under treatment with hydroxychloroquine, antiretroviral agents, antibiotics, and corticosteroids, he was discharged with normal cardiac contractility.

The third case was a 75 year-old man, with no cardiovascular risk factors or notable comorbidities, who attended the emergency room for symptoms of dyspnea and chest pain. Electrocardiography showed inferior wall ST-segment elevation and complete atrioventricular block. He experienced several episodes of primary ventricular fibrillation requiring electrical cardioversion, as well as orotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. Norepinephrine perfusion was started, and primary angioplasty was performed with implantation of a stent in the right coronary artery (figure 1E,F). The echocardiogram showed biventricular dysfunction with right-sided predominance, and the chest radiograph, bilateral pneumonia. Within a few hours the patient died in electromechanical dissociation, with a diagnosis of right coronary artery thrombosis and bilateral SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia.

Finally, the fourth case was a 37 year-old women, obese and with a history of deep venous thrombosis, who attended the emergency room for symptoms of dyspnea and chest pain. Troponin I was found to be elevated, and because of her medical history, urgent CT angiography of the pulmonary arteries was performed, which showed bilateral pulmonary thromboembolism with right ventricular dilation, in addition to patchy peripheral opacities compatible with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia, which was confirmed by PCR (figure 1G,H). Suddenly, she experienced severe, persistent hypotension and severe oxygen desaturation (peripheral saturation < 80%). Despite administration of systemic thrombolysis, the patient died due to cardiogenic shock without reaching the cardiac catheterization laboratory for possible percutaneous treatment.

As illustrated by these 4 cases, cardiogenic shock can develop suddenly in COVID-19 patients and can have different causes. It is essential to perform a differential diagnosis with a view toward etiological treatment. The general approach includes routine measures, such as infusion of amines or implantation of VA-ECMO as a bridge to recovery.1 Myocardial inflammation underlies the acute myocarditis, and SARS-CoV-2 particles have recently been demonstrated in the myocardium of these patients.2 In addition to respiratory and circulatory support measures, treatment includes the use of corticosteroids and immunoglobulins. Stress cardiomyopathy in COVID-19 may be triggered by catecholamine discharge secondary to hypoxemia or sepsis, by myocardial injury related to the systemic inflammatory process, by direct myocardial infection with the virus, or by a mixture of factors.3 Treatment consists of administration of amines and mechanical support in addition to the other therapeutic measures used in COVID-19 (table 1).

Pulmonary thromboembolism is common in the hypercoagulability state provoked by COVID-19 and can lead to cardiogenic shock with high mortality. All available measures should be applied, such as VA-ECMO, thrombolysis, and percutaneous treatment, particularly if there is a contraindication for thrombolysis or if this measure fails. Another thrombotic complication that can cause cardiogenic shock is the development of acute coronary thrombosis in segments proximal to the main coronary arteries. This case was treated with percutaneous stent placement, as is recommended in the related clinical practice guidelines.

One consideration to mention is the absence of pathological studies in these patients, as they were not allowed in our setting at the beginning of the pandemic.

This limited series illustrates the variety and severity of cardiovascular manifestations in COVID-19 patients, including acute myocarditis, stress cardiomyopathy, acute coronary syndrome, and pulmonary thromboembolism.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Á. Sánchez-Recalde is an associate editor of Revista Española de Cardiología. The editorial procedure established in the journal was followed to guarantee impartial management of the manuscript.

.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Luisa Salido Tahoces, Dr. José Luis Mestre-Barcia, Dr. Rosa Ana Hernández-Antolín, and Dr. Ana Pardo Sanz for their critical assessment and in-depth revision of the manuscript.

References

- 1.García-Carreño J., Sousa-Casasnovas I., Devesa-Cordero C., Gutiérrez-Ibañes E., Fernández-Aviles F., Martínez-Sellés M. Reanimación cardiopulmonar con ECMO percutáneo en parada cardiaca refractaria hospitalaria: experiencia de un centro. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2019;72:880–882. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2019.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tavazzi G., Pellegrini C., Maurelli M. Myocardial localization of coronavirus in COVID-19 cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020 doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer P., Degrauwe S., Van Delden C., Ghadri J.-R., Templin C. Typical takotsubo syndrome triggered by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur Heart J. 2020 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]