Highlights

-

•

The guidance on excluding non-English literature in evidence synthesis may not be suitable for topics where studies are likely to be from a non-English geography.

-

•

The routine practice of developing search strategies may not fit the rapidly changing concepts such as COVID-19 and we need living search strategies.

-

•

Out-of-date publishing and indexing policies need to be updated.

Dear Editor,

Nussbaumer-Streit et al. [1] reported a timely study on the exclusion of non-English language reports in systematic reviews but cautiously generalized the implications to rapid reviews rather than systematic reviews. The results complement the guidance in the new edition of the Cochrane Handbook [2]. However, the time of publication of this report coincides with the COVID-19 outbreak that introduces a geographical bias toward the inclusion of non-English literature. Although many researchers will try to publish in English, literature in non-English should not be ignored. We also thought it will be an added value to share our other experiences on literature search for evidence synthesis on COVID-19.

1. Vocabulary chaos and controlled vocabulary

When the first case of COVID-19 was reported on November 17, 2019, neither the virus nor the disease it causes had a name. It is hard to describe and report such a thing in academic literature especially when journals' submission systems can mandate using at least five keywords to describe your work. As a result, researchers started creating names using terms related to geography (e.g., “Wuahan Pneumonia”), some adding a date (“Coronavirus 2019”), and the others having a setting (“Wuhan Seafood Market Pneumonia Virus”).

Until the Coronaviridae Study Group of International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) named it “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2” (SARS-CoV-2) [3] and WHO designated the disease it causes as COVID-19 [4], a variety of designations were used and are still being used to describe the same concept. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were being updated so frequently that it was hard to keep up. My colleague asked “What if they change the Supplementary Concept tomorrow?” Ironically, I had to change my search strategy the following day because MeSH changed the concept from “Wuhan Coronavirus” to “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2.” Fortunately, NLM has documented these changes [5,6]. When some of the Supplementary Concepts become a Subject Heading, they may change again. It may take decades until a well-known concept becomes a subject heading. Recent examples are “Meta-Analysis” and “Systematic Reviews” that were added to MeSH only in 2008 and 2019, respectively, when hitherto they were not even supplementary concepts.

2. Lesson 1: problem—many search strategies, none stable

Librarians and information specialists are frequently asked to design and run searches for literature on COVID-19. Apart from the fact that designing search strategies can be subjective and strategies may vary from one search expert to another, terminology is changing rapidly and search strategies that were accurate when first published can become unreliable and unable to retrieve relevant literature in a consistent manner. Although search experts rely on reported terms by the authors and indexing terms from indexing bodies—both shown to be insufficient for COVID-19—we would all benefit from a single source of truth: a standardized and up-to-date way to find literature on a particular concept. Using a validated search filter could certainly help but the rapid growth of relevant literature and a lack of stable Subject Headings both mitigate against the reliability of this approach.

3. Lesson 2: solution—the first living search strategy

Although COVID-19 is an extreme example, search experts are aware that changes in MeSH (Subject Headings annually and Supplementary Concepts weekly) and Emtree (thrice a year) may mean that search strategies may become out of date within a year and may require an update, and limiting the search to publication date or database entry date may offer only a temporary workaround. In addition, databases may change their records and add, modify, or delete fields that necessitate changes to the syntax of search strategies. The need for living search strategies has always been there, but COVID-19 has brought this need into sharper focus. To date, there has been no open platform to develop living search strategies and search experts have become accustomed to writing searches using word processing programs and sharing them in text documents (e.g., spreadsheet or PDF) with all the limitations this implies [7].

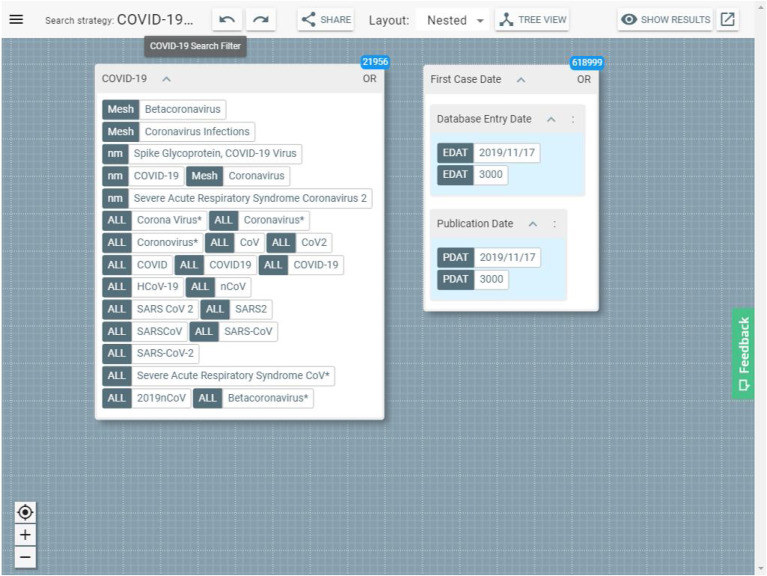

As a response, we offer what may be the first living search strategy with live search results using the 2Dsearch platform. This search strategy is being updated and curated as the concept develops and as the new terminology appears in MeSH via the following permanent link: https://app.2dsearch.com/new-query/5e8072c5e0b7360004cd2b74.

We expect that this search strategy (Fig. 1 ) is going to be updated continually in the coming weeks adding at least the following concepts that are currently (1st April 2020) inactive:

-

•

COVID-19 diagnostic testing (Supplementary Concept)

-

•

COVID-19 serotherapy (Supplementary Concept)

-

•

COVID-19 drug treatment (Supplementary Concept)

-

•

COVID-19 vaccine (Supplementary Concept)

Fig. 1.

Visualization of COVID-19 search strategy.

4. Lesson 3: future—updating publishing and indexing industry

Since criticism continues against the traditional long process of publishing peer-reviewed papers and indexing delays [8], at the time of writing, more than a quarter of studies on COVID-19 are not published in any journal and are not indexed in MEDLINE or Embase. This means that any evidence synthesis effort must consider searching preprint servers such as medRxiv and bioRxiv in addition to ClinicalTrials.Gov at least in rapidly growing topics [9]. It is unfortunate that none of the main bibliographic databases index these unpublished literature sources. This is the time for both academic publishers and indexing bodies to consider whether they are letting science down by not being more inclusive.

Bearing in mind these lessons, search experts such as librarians and other information professionals are designing and sharing search strategies in all the possible ways and formats freely and openly. We hope these efforts could be systematized via a common platform in the near future. At the same time, this pandemic puts a great responsibility on information professionals' shoulders who are volunteering their time and expertise in designing search strategies to answer the most crucial questions. Now more than ever, we need to share what we have learned.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Nussbaumer-Streit B., Klerings I., Dobrescu A.I., Persad E., Stevens A., Garritty C. Excluding non-English publications from evidence-syntheses did not change conclusions: a meta-epidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;118:42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lefebvre C., Glanville J., Briscoe S., Littlewood A., Marshall C., Metzendorf M. Searching for and selecting studies. In: Higgins J.P.T., Thomas J., Chandler J., Cumpston M., Li T., Page M.J., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester (UK): 2019. pp. 67–107. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(4):536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it. https://tinyurl.com/t82w9ka Available at.

- 5.US National Library and Medicine New MeSH supplementary concept record for the 2019 novel coronavirus, Wuhan, China. NLM Tech Bull. 2020;432:b3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.US National Library and Medicine New MeSH supplementary concept record for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) NLM Tech Bull. 2020;432:b7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell-Rose T., Shokraneh F. Designing the Structured search experience: rethinking the Query-Builder Paradigm. Weave J Libr User Experience. 2020;3(1) doi: 10.3998/weave.12535642.0003.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shokraneh F. Lessons learned from COVID19 for science communication: long road from submission to getting indexed in MEDLINE and Embase. https://tinyurl.com/sxk5wkl Available at.

- 9.Shokraneh F. Keeping up with studies on COVID-19: systematic search strategies and resources. BMJ. 2020;369:m1601. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]