Abstract

Objectives

The undergraduate medical students must be made aware of the ethical and humanistic values of cadaveric dissection. This study therefore designed, implemented, and evaluated the impact of the module ‘Cadaver as a Teacher’ (CrAFT) that examines the ethical values of cadaveric dissection.

Methods

This prospective, multimethod study involved 447 first-year undergraduate medical students who had participated in all three sessions of the CrAFT module. Activities included interactive lectures, individual assignments, and a poster-making competition. Students offered a silent tribute and wrote words of gratitude down on a tribute wall. They also expressed their thoughts in the form of essays, poems, and collages. These reflections were qualitatively analysed to generate themes. At the end of the module, an online quiz was conducted to assess the knowledge gained by the students. Their scores were correspondingly recorded and calculated.

Results

The major themes identified were: cadaver as a teacher, acknowledgement and thanksgiving, bonding, and empathy. Out of all the test takers, 316 students (94.32%) scored more than a five out of ten. The students strongly felt that the module effectively sensitised them towards the ethical and humanitarian aspects of handling cadavers.

Conclusions

The implementation of an educational module about cadavers is a novel approach towards sensitising medical students. The students believed that sensitising them early on would have helped them establish a practice grounded in professionalism, human values, and empathy.

Keywords: Ethics, Human cadaver, Humanism, Professionalism, Reflection

الملخص

أهداف البحث

يجب أن يكون طلاب الطب في المرحلة الجامعية على دراية بالقيم الأخلاقية والإنسانية لتشريح الجثث. لذلك، قمنا بتصميم وتنفيذ وتقييم تأثير وحدة "الجثة كمدرس" التي درست القيم الأخلاقية لتشريح الجثث.

طرق البحث

شملت هذه الدراسة المستقبلية متعددة الأساليب ٤٤٧ طالبا من السنة الجامعية الأولى للطب. ضمت الدراسة الطلاب الذين شاركوا في جميع الدورات الثلاث للوحدة. حيث كانت هناك محاضرات تفاعلية ومهام فردية ومسابقة لصناعة الملصقات. قدم الطلاب ثناء صامتا وصاغوا كلمات امتنانهم على جدار التقدير. كما عكس الطلاب أفكارهم في شكل مقالات وقصائد وملصقات. وقد تم تحليل هذه الانعكاسات النوعية لتوليد المواضيع. كما تم في نهاية الوحدة إجراء اختبار عبر الإنترنت لتقييم المعرفة التي اكتسبها الطلاب. وتم تسجيل النتائج المكتسبة وحسابها.

النتائج

كانت الموضوعات الرئيسة التي تم تحديدها؛ الجثة كمدرس، والاعتراف والشكر، والترابط، والتعاطف. حصل ٣١٦ طالبا (٩٤.٣٢٪) على أكثر من خمسة من عشرة درجات. شعر الطلاب بقوة أن الوحدة نجحت في توعيتهم بالجوانب الأخلاقية والإنسانية للتعامل مع الجثث.

الاستنتاجات

إن تطبيق نموذج تعليمي حول الجثة ينتج منهجا جديدا نحو توعية الطلاب. رأى الطلاب أن توعيتهم خلال أيامهم المبكرة من شأنه أن يسهم في رحلتهم لممارسة الاحتراف والقيم الإنسانية والتعاطف.

الكلمات المفتاحية: جثة الإنسان, أخلاق, الإنسانية, انعكاس, احترافية

Introduction

Focusing on humanistic values in the medical curriculum has become increasingly challenging, as medical care has grown to become more technical and medical education has become more centred on procedures. Dissection still plays a key role in the beginning of the medical curriculum as a means of learning the human anatomy.1 Therefore, the dissection hall would be a logical starting point for humanistic education. Being aware of the ethical and humanitarian values of cadaveric dissection could benefit students by widening their perspective on cadavers during the early stages of their education.2

Cadaveric dissection is an ancient yet powerful learning tool for medical students.3,4 The dissection of a body must be carried out in a respectful manner to show continued reverence towards the deceased person until the very end.5 The students undergo such training from the beginning of their curriculum with the intention of sensitising them towards the handling of the cadavers and allowing them to understand the significance of a body donor's contribution, thus creating a remarkable impact on their attitude towards cadavers.6 It is crucial to make medical students aware of the ethical considerations while handling cadavers for educational and research purposes.7 This would serve as an initial step towards showing respect and empathy to patients in their future careers.

In recent decades, undergraduate medical education has undergone considerable changes. Focus is not only directed on acquiring knowledge and obtaining skills, but also on the attitude students develop throughout the learning process.8 Cadaveric dissection continues to serve as a major learning tool for medical undergraduates and it is sustained by the active voluntary body donation programme, which is the medical schools' main source of cadavers. Several medical schools across the globe currently hold introductory sessions for undergraduate medical students before they perform dissections.3,4 However, a defined module for this must still be developed.

The medical council of India (MCI) strongly encourages the incorporation of ethical and attitudinal components in the beginning of undergraduate medical curricula. In 2015, the MCI mandated teaching ethics and humanities as an integral part of the medical curriculum through the Attitude, Ethics and Communication module.9 Correspondingly, this study attempted to design an educational module, implement it, and evaluate its overall impact. The ‘Cadaver as a First Teacher’ (CrAFT) module was created to impart the essential aspects of handling cadavers from the beginning of the academic year of first-year undergraduate medical students.

Materials and Methods

This prospective, multimethod study recruited 447 first-year undergraduate medical students who had taken part in all three sessions of the CrAFT module and were willing to participate.

The designing and implementation of the module took three academic years (i.e. 2015-2018). Upon the approval of the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC28/2017), the module was planned during the one academic year 2016–2017 and named ‘Cadaver as a first teacher’ (CrAFT). Kasturba Medical College has 250 undergraduate medical students annually and the module was intended to be imparted to all of them, considering their voluntary participation after obtaining their informed consent.

Pilot session

During the academic year 2016–2017, this project was piloted on 250 first-year undergraduate medical students. Convenience sampling was utilised as it was relatively easy to solicit student participation during the beginning of the academic year. It included a series of lectures on the importance of cadavers in anatomy and surgery. The students also participated in small group activities wherein they had to reflect on their thoughts in the form of phrases, among other things. However, they were not assessed at the end of the module.

The contents and strategies for the students of forthcoming years were planned based on the student feedback and end-of-module assessment was subsequently added in as well. The major themes included were the ethical values of cadaveric dissection and voluntary body donation. To make the sessions more engaging, a poster-making competition was added. Assessment was incorporated through a reflective writing portion and an online quiz.

Details of designing of the CrAFT module

The faculty of anatomy designed the module during the academic year 2016–2017, keeping in mind the needs of the first-year undergraduate medical students. Interactive lectures along with the small group activities were chosen as the main learning strategies. The interactive lectures conveyed the importance of cadavers in learning anatomy, key ethical issues while handling cadavers, biomedical waste management, and the process of voluntary body donation. The diversity of the activities aided in addressing the complications of planning activities for a heterogeneous learner group. Activities such as reflective writing, poem and essay writing, poster-making, and self-directed learning were all part of the module. A total of 6 h were allocated for the classroom activities, which were divided into three 2-h sessions throughout the academic year. At the end of the module, the students took a multiple-choice online quiz to assess their learnings. Students utilised the institutional e-learning platform EduNxt (owned by Manipal Global Education Services Pvt. Ltd.) for the assessment of the module and giving feedback. The questionnaires (online quiz and feedback) were designed and validated by a team of faculty members from the anatomy and ethics departments.

Implementation of the module

This module was implemented following a prospective, multimethod approach. The qualitative approach mostly suited the grounded theory as the students were expected to come up with new ideas, attitudes, and practices while handling the cadaver. The analysis of the online quiz was done through a quantitative approach. Four hundred and forty-seven first-year medical undergraduates of academic years 2017–2018 (N = 248) and 2018–2019 (N = 199) voluntarily participated in the module over two academic years. The students who did not wish to participate or were absent on those days (N = 53) were excluded. The module mainly comprised three sessions.

Session 1: sensitising students and offering a silent tribute

The first session of the module was conducted in the first week of the academic year. During the session, the students attended interactive lectures in a large group of 250. The lectures focused on the importance of cadavers in learning anatomy, voluntary body donation, ethical issues, and biomedical waste management. Each lecture did not exceed 20 min. The students were given time to interact with the resource faculty and ask questions. A tribute wall was created at the entrance to the dissection hall, which read ‘Corporis Humani: A glorious tribute’. During its inauguration, students were encouraged to express their gratitude towards the cadavers through words. The session was concluded with students offering a silent tribute to the departed souls who donated their bodies for the sake of medical education.

Session 2: individual and group activities by the students (qualitative assessment)

In the middle of the academic year, the students participated in small group and individual learning activities. The students individually shared their personal views on learning anatomy by means of cadaveric dissection through reflections, poems, essays, and collages. The Faculty of Anatomy, who was not involved during the first session, coded the information and derived the major themes by analysing the said reflections, poems, and essays. After the analysis, all the writings were stored in the repository of the Department of Anatomy. The students also participated in a poster-making competition with the theme ‘cadaver as a teacher’. The students made posters in small groups of 12–13 students and presented them in front of a panel, which included an anatomist and a bioethics expert. The posters were graded based on their content, creativity, and display. The students were also encouraged to write on the tribute wall. As an incentive, the students with the best posters were awarded.

Session 3: thanksgiving and reflections

A thanksgiving session was organised towards the end of the academic year. On this occasion, the students read their reflections, poems, and essays as a token of gratitude towards the people who offered their bodies to science.

Quantitative assessment of the module

A week after the first session, the students were asked to answer an online graded quiz through the e-learning portal to measure the knowledge they acquired through this module. The quiz was planned within a week to keep the students from accessing information from external sources and to avoid confounding factors, if any. There were ten multiple-choice questions on the voluntary body donation programme, ethical aspects related to the use of cadavers, and biomedical waste management (Annexure 1).

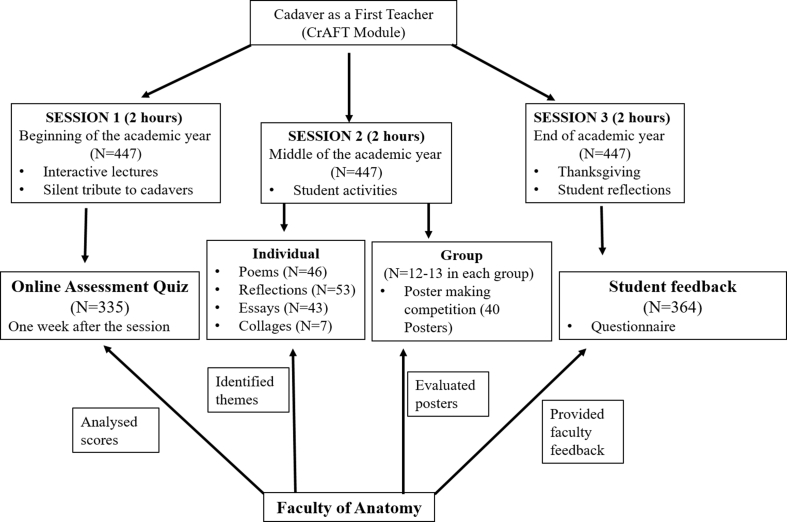

The total scores of the assessment quiz were calculated and the number of students who had a score of 10 (i.e. a perfect score), >8, 5–7, and <5 were categorised. Those who scored more than a five were considered to have passed the quiz. Figure 1 provides a total outline of the module in the form of a flow diagram.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram outlining the entire CrAFT module.

Additionally, the students also completed a Likert scale questionnaire to give their feedback on the module. The responses ranged from ‘strongly disagree1’ to ‘strongly agree5’. The students also reflected on their learning experience and provided their opinions in the end of the first year (Annexure 2). The Faculty of Anatomy also provided their feedback on the delivery and content of the module during this time. Although the faculty feedback was not taken as a part of this study, it was considered in the evaluation of the module in order to make further improvements.

Following the successful implementation of the module for two academic years, the CrAFT module was eventually integrated into the first year anatomy curriculum of Kasturba Medical College, Manipal.

Results

Qualitative analysis of the students' reflections

A total of 447 students (232 males and 215 females) participated in this module over the course of two academic years. The age of the students ranged from 18 to 20 years old. A total of 46 poems, 53 reflections, 43 essays, and 7 collages were analysed over this two-year period.

The students' active participation in reflective writing in itself was considered as an indicator of a change in their attitude. The students highlighted the importance of the cadaver as a learning tool and the noble act of voluntary body donation through reflections, poems, and collages. Every poem and reflection was unique in its own way and highlighted different key elements from which the major themes were derived. The faculty manually coded the reflections using three elements: the meaning of the cadaver, attitudes/gestures, and emotional effects/changes. After coding, the faculty picked out the most highly repeated words and phrases to establish the major themes.

The first theme is ‘Cadaver as a Teacher,’ wherein the students described the cadaver as much more than just a dead body. Learning through cadaveric dissection was something like the ‘dead’ teaching the ‘living’, which was a fascinating way to describe the process.

‘The cadaver is indeed a silent and the first teacher who has left a mark on the student's heart.’

One student wrote, ‘The importance of seeing and being able to visualise the nerves, muscles, and vessels is paramount. This is where the cadaver takes the role of our first teacher.’

Learning through cadaveric dissection helps students build teamwork while learning. One student reflection read, ‘Learning with a cadaver provides a hands-on experience of anatomy and it helps to build teamwork as a group of students learn together.’

For the students, a cadaver, although silent, reveals countless stories and prompts them to think about the person who donated his or her body. ‘To us, your silence speaks volumes.

Your unrelenting patience humbles us all. The knowledge you impart, like fire, consumes.

And into the endless depths of learning, we fall.’ (Annexure 3).

The students realised the importance of handling the cadaver with respect and how this would lead them to respect their patients in the future as well. ‘We now refer to it as our cadaver and we handle it with the utmost care and make sure that others do so too.’

The second theme is ‘Acknowledgement and Thanksgiving.’ The students highlighted the need to acknowledge the donor's family members and voiced their opinions in the following manner:

‘Donating one's body is much beyond amere process of signing the agreement, but involves support from one's family to fulfill the wish after the donor's death.’

The students also reflected on the importance of the family in deciding on body donation. ‘There is an unspoken history about every cadaver that was once part of someone's family.’

It made them think about the noble act of body donation as a sacrifice made for education. ‘Handling a person's dead body who was once alive has made one rethink about the sacrifice he made by donating his body.’

‘I had never thought, the dead could teach the living

Knowledge is the gift they are giving.

I thank you, as everyone should

You teach something no living ever could.’

Thethird themeidentified is ‘Bonding and Empathy.’

The students expressed that ‘Learning with the cadaver has helped build a bond between a doctor and a patient.’

One student mentioned that the ‘Cadaver changed the perspective of humanity.’

The students acknowledged the development of a long-term bond that formed among them while dissecting the cadaver. ‘The way one handles the cadaver reflects about one's self.’ ‘Learning with the cadaver has made me relate to the classes with ease where I have managed to establish a respectful relationship with it. In the future, it is this respectful bond that would lead me to have respectful relations with my patients as a physician.’

The students felt empathy, stating that the ‘cadaver’ was once a ‘person’. ‘I wonder how hard he must have worked with those hands. I wonder how he talked, what made him angry, and now, he lies still, motionless, devoid of emotions, in the hands of young medical students.’

Poster-making competition

Students in small groups of 12–13 members prepared 40 posters over the course of two academic years. The students expressed their creativity through their posters where they conveyed their thoughts on the ethical and humanitarian aspects of cadaveric dissection as well as the process of body donation.

Each poster was unique and conveyed a diverse range of views through vivid imagery. A number of them centred on the importance of cadaveric dissection and the noble act of body donation (Annexure 4).

All the posters were exhibited in the dissection hall for the entire academic year, maximising the exposure of each artwork. The three best posters were recognised and the students in the winning groups were awarded.

The tribute wall was soon filled with words of gratitude for the donors. Students used their creativity to pen down their thoughts through reflections and poems. The tribute wall could accommodate only three to four-posters. Therefore we displayed the prize-winning posters on the tribute wall and the rest, in the dissection hall.

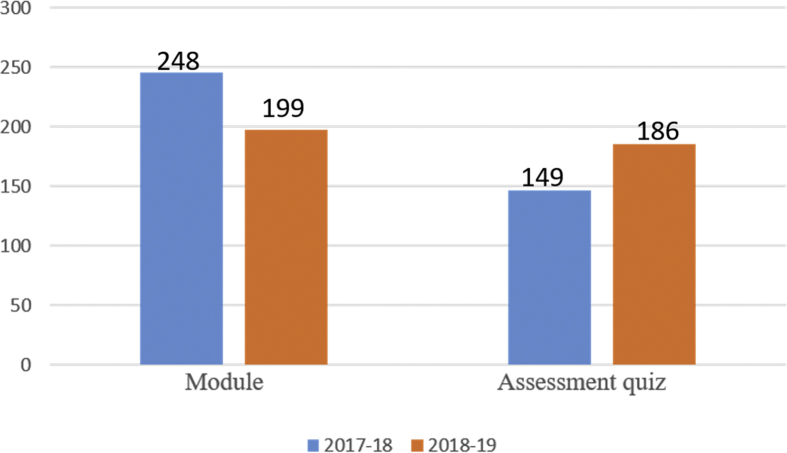

Analysis of the assessment quiz

As previously mentioned, 447 first-year undergraduate medical students participated in the CrAFT module for two academic years. However, only 335 out of the 447 students participated in the assessment quiz. Figure 2 shows the year-wise student participation in detail.

Figure 2.

Graph describing student participation in the module and assessment.

Test results revealed that 25 students got a perfect score and 193 students got more than eight questions right. However, 98 (29.2%) students scored between five and seven and only 19 (5.67%) students scored less than five over two academic years, while 316 students (94.32%) had scored more than five. The students' assessment quiz results at the end of the module indicated that the students had acquired the necessary knowledge. Table 1 shows the number of students that belong to a certain score range in descending order for the two academic years separately.

Table 1.

Number of students and their respective assessment quiz scores.

| Academic year | 10 | >8 | 5–7 | <5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017–18 (N = 149) | 16 | 93 | 27 | 13 |

| 2018–19 (N = 186) | 9 | 100 | 71 | 6 |

Student feedback

The students reflected on their learning experience at the end of their academic year through a Likert scale questionnaire. They also added their comments regarding the execution of the module. Out of the 447 students who participated in the sessions, 364 students gave their feedback. However, it must be noted that some of the students who did not participate in the assessment quiz provided feedback. The mean value for each response was calculated along with the median and mode (Table 2). The students strongly agreed that the module sensitised them towards the respectful handling of cadavers (i.e. the most frequently occurring value was 5).

Table 2.

Responses to the Likert scale feedback questionnaire. The responses were: strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neutral (3), agree (4), strongly agree (5).

| Response | Total (N) | Mean | Median | Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The module promoted empathy and feelings | 358 | 3.75 | 4 | 4 |

| The activities were creative and enjoyable | 347 | 3.65 | 4 | 4 |

| The activities increased thinking capacity | 351 | 3.64 | 4 | 4 |

| The activities provided opportunities to share ideas with others (i.e. group members) | 364 | 3.79 | 4 | 4 |

| The module sensitised the students towards their future professional life | 349 | 3.73 | 4 | 4 |

| The module highlighted the importance of the respectful handling of cadavers | 339 | 3.97 | 4 | 5 |

| The activities improved imagination | 342 | 3.68 | 4 | 4 |

| The module was a refreshing break from routine classes | 360 | 3.70 | 4 | 4 |

| The activities promoted lateral thinking | 354 | 3.73 | 4 | 4 |

Students felt that the module fostered in them the ethical values needed in cadaveric dissection. It made them respect the people who donated their bodies for them to learn from in this noble profession. It also enhanced their imagination and made them more creative.

Faculty viewpoint

Out of the 17 members of the Faculty of Anatomy, 12 provided their feedback on the content and execution of the module. The teaching experience of the faculty ranged from 3 to 15 years. All 12 faculty members indicated that the contents of the module covered the necessary topics and successfully made the students aware of the ethical aspects related to cadavers and body donation. Each of them also strongly felt that the practice of reflective writing should be promoted and that the module should be implemented and turned into a mandatory part of the teaching curriculum. Six faculty members agreed that there was a marked change in the attitude of the students as the latter handled the cadaver with respect and refrained from taking photographs of it. However, 3 faculty members did not share the same opinions.

Discussion

This study examined the design, implementation, and effects of the CrAFT module. The participating students reflected on the module and agreed that it effectively helped them understand the essential ethical values in cadaveric dissection. Several studies have actually been done on the ethical considerations of cadavers and body donation in the past.5,10,11 These studies revealed that medical students consider the dissection of cadavers as one of the most accepted methods of learning anatomy.12,13 The current literature advocates the preservation of the humanities in medical education. Emphasising such humanitarian and ethical values among medical students would foster social responsibility and enhance the quality of patient care.2

Honouring body donors to show gratitude towards their noble sacrifice is an esteemed act in itself. In a chapter of his book, Da Rocha discusses an ecumenical ceremony, which is organised by medical students in Brazil during the end of an academic year to honour the body donors in the presence of professors and the donors' families.14 Physical therapy student participants narrated their experience of learning through cadavers to their groups and ‘Humanities in Gross Anatomy Projects’ (HuGA) was one of the approaches discussed. The students wrote poems, narratives, songs, etc. and were evaluated based on a grading criteria.15 Similarly, the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science in Rochester, USA also conducted a thanksgiving ceremony ‘Convocation of Thanks’, which provided an opportunity for the students to acknowledge the body donors and reflect upon their noble gesture.16 However, in this study, sessions were spread throughout the academic year and the students were sensitised towards body donation and ethics. They were able to reflect on their learning experiences during the thanksgiving session.

The survey highlighted the guidelines adopted by medical schools to ensure respectful handling of human cadavers during dissection and the traditional ways to honour them. There is a need for good practices in human cadaveric dissection in order to bring together science and humanity.17 A review asserts the importance of family consent in the process of body donation and states that the public display of bodies and usage of unclaimed bodies must be revisited.18

In a medical school in the United States, the students regard the cadaver as a ‘teacher’ rather than a ‘patient’. They believe that such ‘body as teacher’ approach is more effective in promoting respect and empathy towards the cadaver and future patients. Additionally, this approach also facilitates the students' emotional development.19 The present study incorporates a similar concept to ‘cadaver as a teacher’, which serves to impart the ethical and humanitarian aspects related to handling cadavers to students.

Providing a memorial to the body donors is one of the major components of anatomy education and is an emerging strategy to pay respects to them.20 Several medical schools have already incorporated strategies to sensitise medical students towards the respectful handling of cadavers.3,4,15 Medical schools are also practising the ‘silent mentor’ programme to interact with the donor's family members. The students get to know the history of the donor through their family and pay tribute to the donors in the end of the academic year. As a result, this practice has successfully increased the number of voluntary donors and imparted a sense of empathy and compassion to the students.3,4,21,22 Furthermore, the effect of watching the movie ‘Anatomy and Humanity’ was evaluated in a medical school and the authors found a more positive initial reaction to the cadaver. Students also experienced a decrease in emotions like sadness and guilt with respect to the anatomy laboratory.23 Similarly, a current study confirmed that students who understood the importance of respectful handling of cadavers offered a tribute to the body donors' departed souls to express their gratitude.

Reflective writing among medical students has also gained popularity in medical education in recent years.24,25 At the State University of New York, USA, students are asked to reflect on cadaver dissections and create a narrative or an imagined life story of the cadaver. In this manner, they are able to explore their personal experiences and express their goals of professional growth through narrative writing. The authors categorised the themes, which included initial apprehensions, detachment, curiosity about the cadaver's life, the need for student-cadaver connection, self-questioning about the motivation to donate one's body, gratitude, and religious or existential reflection.26 Student feedback on the memorial ‘convocation of thanks’ for the donors at the University of Vermont revealed that it had a positive impact on both the students and the donor families. ‘Personhood of the donors’ was the major theme identified.27 Three major themes were identified in the present study, based on student reflections, essays, and poems1: Cadaver as a teacher,2 giving thanks, and3 acknowledgement, bonding, and empathy. To a certain extent, these themes are essentially the same as respect and empathy as well as those identified by the study of Coulehan et al.

The CrAFT module developed in the current study addresses the ethical and humanitarian aspects related to voluntary body donation and cadaveric dissection. The students mentioned that the module enlightened them about the ethics and values in cadaveric dissection. With the knowledge they obtained, the students could reciprocate respect and empathy towards the body donors through their words and acts of gratitude. However, the students did not have the opportunity to interact with the donors' families, as the body donors' identities are kept confidential in this institute. Notably, not all students participated in the assessment quiz and individual activities. However, they did take part in the poster-making event, which was a group activity.

Limitations of the study

Despite the presence of 250 medical undergraduates, not all of them took the module. Moreover, it was challenging to keep all the students motivated to actively participate throughout the academic year. The reduction of time intervals between the sessions will be considered when planning future modules. In addition, planning a module with a shorter duration (i.e. one that does not go on for an entire academic year) may also aid in sustaining student engagement. These must all be explored in future research.

Conclusion

The three sessions of the CrAFT module had a positive impact on the knowledge as well as the attitude of the students. In particular, the students were able to gain adequate knowledge about the ethical aspects in cadaveric dissection by the end of the module. The module also enabled them to reflect on themselves while highlighting the value of the respectful handling of cadavers. According to their reflections, the students revealed that the module nurtured in them the values of professionalism, human values, and empathy. The implementation of such an educational module was a novel approach to foster students' awareness regarding the ethics and values of cadaveric dissection. However, the effectiveness of such a module in the students' careers in the long run must be explored further.

Conference Presentation

The abstract of this research paper was accepted for an e-poster presentation in AMEE 2019 that was held from August 24–28 in Vienna, Austria. Dr. Anne D. Souza presented the poster and was awarded one free registration to attend the conference.

Source of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. All expenses incurred were borne by the Department of Anatomy.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Provided by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC28/2017).

Authors contributions

AD & SRK planned the project and executed the methods, collected the data, and prepared the original draft. PR was the main person in the conceptualization of this project. PR & AKP contributed by critically reviewing the draft manuscript. SGK supervised the project and provided resources for its execution. She also contributed to the preparation of the draft manuscript.

Acknowledgment

Heartfelt thanks to all the faculty of the Anatomy Department for helping in designing and executing this module. Especially the authors thank Dr. Prasanna L C and Dr. Lydia Quadros for coordinating the poster competition. The authors wish to thank Dr. Prakash Babu, Dr. Mamatha Hosapatna, and Dr. Vrinda Ankolekar, Dr. Suhani Sumalatha, for evaluating the reflections, poems, and essays. Thanks to Mr. Vijaya of the Department of Anatomy (technical), for photographing all the events for documentation.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Taibah University.

References

- 1.Rizzolo L.J. Human dissection: an approach to interweaving the traditional and humanistic goals of medical education. Anat Rec. 2002 15th December;269(6):242–248. doi: 10.1002/ar.10188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halperin E.C. Preserving the humanities in medical education. Med Teach. 2010;32(1):76–79. doi: 10.3109/01421590903390585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiou R.-J., Tsai P.-F., Han D.-Y. Effects of a “silent mentor” initiation ceremony and dissection on medical students' humanity and learning. BMC Res Notes. 2017 Sep 16;10(1):483. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2809-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saw A. A new approach to body donation for medical education: the silent mentor programme. Malays Orthop J. 2018 Jul;12(2):68–72. doi: 10.5704/MOJ.1807.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bob M.H., Popescu C.A., Armean M.S., Suciu S.M., Buzoianu A.D. Ethical views, attitudes and reactions of Romanian medical students to the dissecting room. Rev Medico-Chir Soc Medici Ş̧i Nat Din Iaş̧i. 2014;118(4):1078–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones D.G., King M.R. Maintaining the anonymity of cadavers in medical education: historic relic or educational and ethical necessity? Anat Sci Educ. 2017;10(1):87–97. doi: 10.1002/ase.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Champney T.H. The cadaver on the cover. Acad Med. 2010 Mar;85(3):390. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181cc9889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norman G. Medical education: past, present and future. Perspect Med Educ. 2012 Mar;1(1):6–14. doi: 10.1007/s40037-012-0002-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitra J., Saha I. Attitude and communication module in medical curriculum: rationality and challenges. Indian J Publ Health. 2016 1st April;60(2):95. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.184537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenner E., Pais D. The philosophy and ethics of anatomy teaching. Eur J Anat. 2014;18(4):353–360. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkinson T.M. Respect for the dead and the ethics of anatomy. Clin Anat. 2014;27(3):286–290. doi: 10.1002/ca.22263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azer S.A., Eizenberg N. Do we need dissection in an integrated problem-based learning medical course? Perceptions of first- and second-year students. Surg Radiol Anat SRA. 2007 Mar;29(2):173–180. doi: 10.1007/s00276-007-0180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho M.J., Hwang Y. Students' perception of anatomy education at a Korean medical college with respect to time and contents. Anat Cell Biol. 2013 Jun;46(2):157–162. doi: 10.5115/acb.2013.46.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Da Rocha A.O., Bonatto-Costa J.A., Pedron J., De Moraes M.P.O., De Campos D. Commemorations and memorials: exploring the human face of anatomy. 2017. The ceremony to honor the body donor as part of an anatomy outreach program in Brazil; pp. 157–172. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canby C.A., Bush T.A. Humanities in gross anatomy project: a novel humanistic learning tool at des moines university. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3(2):94–96. doi: 10.1002/ase.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pawlina W., Hammer R.R., Strauss J.D., Heath S.G., Zhao K.D., Sahota S. The hand that gives the rose. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(2):139–144. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh S.K. Paying respect to human cadavers: we owe this to the first teacher in anatomy. Ann Anat. 2017;211:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones D.G. Using and respecting the dead human body: an anatomist's perspective. Clin Anat. 2014;27(6):839–843. doi: 10.1002/ca.22405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohl M., Bosch P., Hildebrandt S. Medical students' perceptions of the body donor as a “First Patient” or “Teacher”: a pilot study. Anat Sci Educ. 2011;4(4):208–213. doi: 10.1002/ase.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goran S., Nalini P. World Scientific; 2017. Commemorations and memorials: exploring the human face of anatomy; p. 215. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong M.-K., Chu T.-Y., Ding D.-C. How the silent mentor program improves our surgical level and safety and nourishes our spiritual life. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2017;6(3):99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.gmit.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin S.C., Hsu J., Fan V.Y. “Silent virtuous teachers”: anatomical dissection in Taiwan. BMJ. 2009 Dec 16;339:b5001. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dosani F., Neuberger L. Anatomy and humanity: examining the effects of a short documentary film and first anatomy laboratory experience on medical students. Anat Sci Educ. 2016;9(1):28–39. doi: 10.1002/ase.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandars J. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Med Teach. 2009;31(8):685–695. doi: 10.1080/01421590903050374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ottenberg A.L., Pasalic D., Bui G.T., Pawlina W. An analysis of reflective writing early in the medical curriculum: the relationship between reflective capacity and academic achievement. Med Teach. 2016;38(7):724–729. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1112890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coulehan J.L., Williams P.C., Landis D., Naser C. The first patient: reflections and stories about the anatomy cadaver. Teach Learn Med. 1995;7(1):61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greene S.J., Collins A.J., Rosen L. A memorial ceremony for anatomical donors: an investigation of donor family and student responses. Med Sci Educ. 2018;28(1):71–79. [Google Scholar]