Highlights

-

•

COVID-19, caused by the novel SARS-CoV-2, is a pandemic without a known treatment.

-

•

COVID-19 cannot be distinguished from other viral infections based on symptoms.

-

•

COVID-19 and influenza-A coinfection presents with clinically important features.

-

•

Treatment of influenza-A coinfection could improve COVID-19 coinfection outcome.

-

•

Systematic analysis of CT and CXR images is important to follow disease resolution.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Influenza, Co-infection

Abstract

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), is spreading globally and poses a major public health threat. We reported a case of influenza A virus and SARS-CoV-2 co-infection. As the number of COVID-19 cases increase, it will be necessary to comprehensively evaluate imaging and other clinical findings as well as consider co-infection with other respiratory viruses.

Introduction

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), is spreading globally and poses a major public health threat [1]. No effective treatment has yet been established and severe morbidity and mortality have been reported to be higher in the elderly and patients with underlying diseases [2]. COVID-19 often starts with non-specific upper respiratory tract symptoms, making it difficult to distinguish from those of other diseases [3]. In particular, influenza virus infections may present similar symptoms as those of COVID-19. The current lack of clinical knowledge about COVID-19 might, therefore, lead to bias and missed diagnoses in cases of co-existing infections. In our hospital, we encountered a case of influenza A virus and SARS-CoV-2 co-infection, which allowed us to analyse the overlapping clinical course of these two viral infections.

Case report

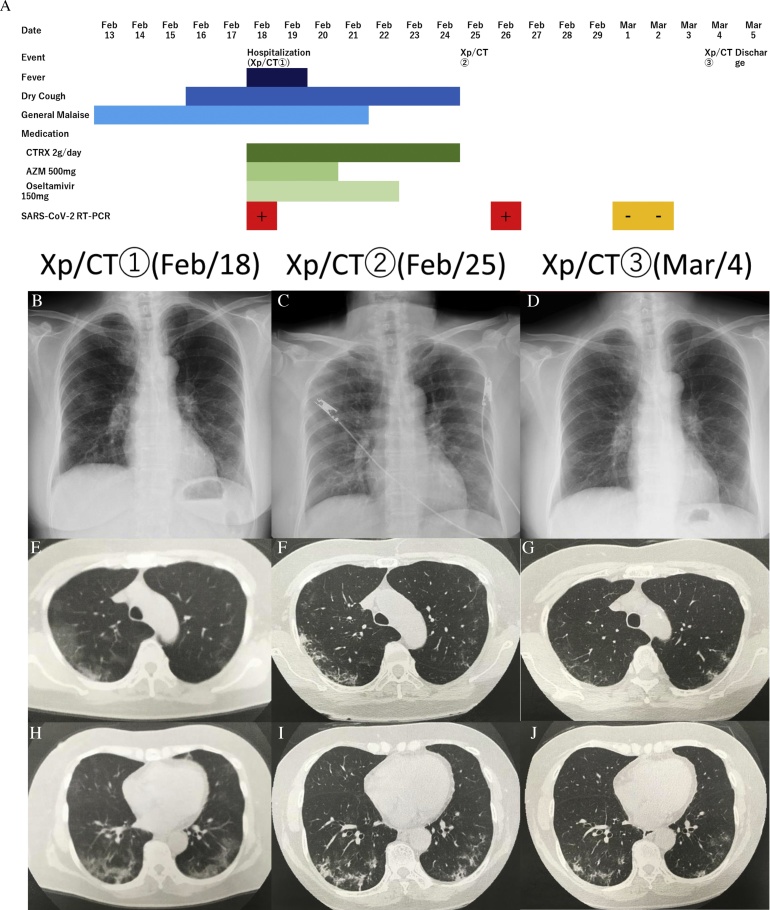

A 78-year-old woman, a non-smoker with dyslipidemia and hypothyroidism presented to her primary care physician on 13 February with general malaise and anorexia lasting several days. She did not have other symptoms, such as fever, cough, sputum, or dyspnoea. She had visited Paris, France, from 30 January to 4 February 2020. At that time, her vital signs were within normal limits, including SpO2 (i.e., 98 % on room air) (Fig. 1A). On 18 February, she complained of cough and exacerbation of malaise and anorexia and had an associated 3 kg body weight loss. She was referred to our hospital because of a bilateral reticular shadow seen on chest X-rays (Fig. 1B) and ground-glass opacity (GGO) adjacent to the pleura seen on chest computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 1C, D). At the time of her visit, she had a temperature of 37.7 °C; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; heart rate, 106 beats/min (regular); blood pressure, 139/63 mmHg; and SPO2 of 95 % on room air. Admission blood tests showed elevated C-reactive protein (7.9 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (106 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (80 U/L), γ-glutamyltransferase (153 U/L), alkaline phosphatase (372 U/L), and lactate dehydrogenase (383 U/L). Other blood test results were within the normal range. COVID-19 was suggested based on her prolonged clinical symptoms, travel history, and chest X-ray and CT findings. We thus performed a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay of a sputum specimen for SARS-CoV-2 detection. A rapid influenza test, conducted simultaneously, was positive for influenza A virus, and she was started on oseltamivir with ceftriaxone 2 g/day and azithromycin 500 mg/day to cover possible bacterial infections.

Fig. 1.

A: Clinical course of a patient with the SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A virus infection. B: Chest radiograph obtained during admission shows a bilateral reticular shadow. C, D: Computed tomography (CT) scan obtained during admission shows ground-glass opacity adjacent to the pleura. E: Chest radiograph obtained on the 8th day of admission showing a bilateral consolidation and a reticular shadow. F, G: CT scan obtained on the 8th day after admission shows consolidation. H: Chest radiograph obtained before discharge shows an improvement of the previously noted consolidation. I, J: CT scan obtained before discharge shows an improved consolidation.

One day after oseltamivir initiation, on 19 February, she became afebrile. The PCR assay performed on admission tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on 20 February. By 21 February, her general malaise had worsened. Chest X-ray (Fig. 1E) and CT (Fig. 1F, G), re-examined on 25 February, showed improvements in previously noted GGO, appearing more like a consolidation. Given the improvement in her clinical symptoms and CT findings, another PCR assay for SARS-CoV-2 detection was performed on 26 February which tested still positive. Subsequent SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing on 1 and 2 March tested negative, and the patient was discharged on 5 March. Chest X-ray (Fig. 1H) and CT (Fig. 1I, J) images obtained a day before discharge showed improvements of previously noted consolidation and GGO. She did not require oxygen therapy throughout her hospital stay.

Discussion

Herein, we reported a case of influenza A and SARS-CoV-2 co-infection. Although the exact infection timing of the two viruses is unknown, this case reveals some important clinical features of COVID-19. Considering that the patient became afebrile one day after receiving the anti-influenza drug, oseltamivir, her initial fever at the time of admission was presumably due to influenza. Although the PCR results for SARS-CoV-2 were not yet known during fever resolution, she was still presumed to be positive COVID-19, based on the imaging findings and medical history consistent with the disease. Thus, it is important to suspect COVID-19 and respond accordingly while awaiting test results.

In this case, systemic symptoms such as generalized malaise and anorexia preceded dry cough respiratory symptoms. Huang et al. reported that in 41 patients, common symptoms included fever (98 %), cough (76 %), dyspnea (55 %), and myalgia or general malaise (44 %) [4]. Moreover, Guan et al. analysed 1099 cases and found the most common symptoms were fever (43.8 % on admission and 88.7 % during hospitalization) and cough (67.8 %) [5]. As shown, we cannot distinguish between influenza and COVID-19 based only on clinical symptoms.

Problems with the diagnostic accuracy of rapid diagnostic tests and PCR assays for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 have been highlighted. Wu and colleagues emphasised the possible underestimation of COVID-19 due to high rate of false-negative tests for upper respiratory specimens or in co-infection cases with other respiratory viruses [6]. Given the current diagnostic rates of both SARS-CoV-2 and influenza viruses, it is not clinically appropriate to exclude prevalent viral infections from the test results [7].

We were able to sequentially evaluate the chest CT findings. During hospitalization, GGO adjacent to the pleura was observed [8]. During the patient’s clinical course, the GGO changed towards consolidation and disappeared at discharge. This progression is consistent with those mentioned in previous COVID-19 reports, and the image findings were likely attributable to the disease.

In the future, as COVID-19 cases increase, it will be necessary to comprehensively evaluate imaging and other clinical findings as well as consider possible co-infection with other respiratory viruses.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Eiju General Hospital, an affiliate of the Research Institute for Life Extension.

Funding

This research was partly supported by a Research Program on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases from AMED (19fk0108113).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- 1.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lian J., Jin X., Hao S., Cai H., Zhang S., Zheng L. Analysis of epidemiological and clinical features in older patients with corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) out of Wuhan. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa242. pii:ciaa242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatraju P.K., Ghassemieh B.J., Nichols M., Kim R., Jerome K.R., Nalla A.K. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region – case series. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. Epub 2020 Jan 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu X., Cai Y., Huang X., Yu X., Zhao L., Wang F. Co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A virus in patient with pneumonia, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(6) doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding Q., Lu P., Fan Y., Xia Y., Liu M. The clinical characteristics of pneumonia patients coinfected with 2019 novel coronavirus and influenza virus in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi H., Han X., Jiang N., Cao Y., Alwalid O., Gu J. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(4):425–434. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]