Abstract

目的

观察长效沉默热休克蛋白(Hsp)27基因后头颈部鳞状细胞癌细胞生物学行为的改变。

方法

实验分为3组:高滴度pLenti-shRNA-Hsp27慢病毒颗粒长效转染入UM-SCC-22B细胞为实验组(shHsp27组),常规培养UM-SCC-22B细胞(ctrl组)为空白对照,UM-SCC-22B细胞转染pLenti-shRNA-ctrl慢病毒颗粒(shctrl组)为阴性对照。采用实时荧光定量聚合酶链反应和蛋白质印迹法检测各组中Hsp27的表达,采用MTS细胞增殖实验、细胞划痕实验及Matrigel侵袭实验,观察各组Hsp27表达抑制后UM-SCC-22B细胞的增殖、迁移和侵袭能力的变化。

结果

shHsp27组的Hsp27表达明显降低;MTS细胞增殖实验可见,细胞培养24、48 h后,shHsp27组的细胞增殖能力与ctrl组和shctrl组无明显差异;划痕实验表明,划痕产生72 h后,ctrl组细胞迁移能力为shHsp27组的4.38倍;Matrigel侵袭实验显示,ctrl组细胞的体外侵袭能力为shHsp27组的2.03倍。

结论

长效转染慢病毒颗粒pLenti-shRNA-Hsp27能够高效、特异地沉默高转移潜能头颈部鳞状细胞癌细胞系UM-SCC-22B的Hsp27基因表达,并能显著抑制其体外侵袭和转移能力。

Keywords: 热休克蛋白27, 人头颈部鳞状细胞癌, 转移, 慢病毒转染

Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to observe the metastatic behavior of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells after knocking down heat shock protein (Hsp) 27.

Methods

The experiment was divided into three groups: the lentivirus vector plasmid of pLenti-shRNA-Hsp27 was transfected into UM-SCC-22B cells as experimental group (shHsp27 group), routine culture of UM-SCC-22B cells as blank control (ctrl group), UM-SCC-22B cells transfection of pLenti-shRNA-ctrl lentivirus vector as negative control (shctrl group). Through real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and Western blot assay to detect the mRNA expression of Hsp27 in three groups. MTS assay was performed to detect cell-proliferation changes, wounding healing assay was performed to detect cell-migration changes, and Matrigel Transwell invasion assay was performed to detect cell-invasion changes.

Results

The expression of Hsp27 in shHsp27 group decreased significantly; MTS assay showed that UM-SCC-22B before and after Hsp27 knockdown had similar proliferation rates after being cultured for 24 or 48 h. Compared with the ctrl group, the shHsp27 group decreased the metastatic behavior by 4.38-fold in migration and 2.03-fold in cell invasion.

Conclusion

Stably transfected lentivirus vector plasmid of pLenti-shRNA-Hsp27 can efficiently decrease Hsp27 expression and reduce the metastasis ability of UM-SCC-22B.

Keywords: heat shock protein 27, human head and neck squamous cell cancer, metastasis, lentivirus transfection

热休克蛋白(heat shock protein,Hsp)是一种在进化过程中存在着高度保守性的分子伴侣家族,能够阻止肿瘤细胞凋亡,且与其转移有密切关系[1]。Hsp27是小热休克蛋白家族的重要一员,在细胞受到不良刺激时产生,以保护细胞免受环境中自由基、热、缺血和毒性物质等各种应激因素导致的损伤,已被证实在细胞分子信号通路的调节,细胞生长、分化和恶化等方面起着重要作用[2]–[4]。近年来,有报道[5]–[9]显示Hsp27与多种肿瘤的发生和转移有关。在课题组前期研究[10]中,成功建立了头颈部鳞状细胞癌转移模型,发现头颈部鳞状细胞癌Hsp27随其转移潜能的增加,表达丰度升高。为了进一步研究证实Hsp27在头颈部鳞状细胞癌转移中的作用,本研究构建Hsp27短发夹RNA(short hairpin RNA,shRNA)慢病毒载体,转染高转移潜能头颈部鳞状细胞癌细胞UM-SCC-22B,观察长效沉默Hsp27后其转移生物学行为的改变。

1. 材料和方法

1.1. 材料

Hsp27 shRNA慢病毒载体质粒pLKO.1(Open Biosystem公司,美国);pLKO.1空白对照质粒为美国密歇根大学载体中心自行构建并鉴定;病毒颗粒pLenti-shRNA-Hsp27/pLenti-shRNA-ctrl由密歇根大学载体中心包装生产。

细胞系UM-SCC-22B为美国密歇根大学肿瘤中心Thomas.E.Carey实验室保存头颈部鳞状细胞癌高转移潜能细胞系,是下咽部原位鳞状细胞癌同期淋巴转移灶细胞;所有细胞均于37 °C、5%CO2细胞培养箱内常规孵育。

改良伊格尔培养基(Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium,DMEM)、胎牛血清、0.25%胰蛋白酶、双抗(青霉素100 µg·mL−1,链霉素100 µg·mL−1)(GIBCO公司,美国);Trizol试剂(Invitrogen公司,美国),RNA逆转录试剂盒、引物合成及实时荧光定量聚合酶链反应(real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction,RT-qPCR)试剂盒(Applied Biosystems公司,美国),抗Hsp27/β肌动蛋白单克隆抗体(Cell Signaling Technology公司,美国),二抗(Santa Cruz Biotechnology公司,美国),CellTiter 96® AQueous非放射性细胞增殖检测(简称MTS细胞增殖实验)试剂盒(Sigma公司,美国),Matrigel细胞侵袭小室(BD BioSciences公司,美国),二喹啉甲酸(bicinchoninic acid,BCA)蛋白质浓度测定试剂盒(Thermo Scientific公司,美国)。

1.2. 体外转染慢病毒颗粒

1)实验分组:空白对照使用常规培养的UM-SCC-22B细胞,记为ctrl组;阴性对照使用UM-SCC-22B细胞转染pLenti-shRNA-ctrl慢病毒颗粒,记为shctrl组;UM-SCC-22B细胞转染pLenti-shRNA-Hsp27慢病毒颗粒作为shRNA慢病毒转染的实验组,记为shHsp27组。

2)慢病毒转染方法:将对数生长期的UM-SCC-22B细胞接种于100 mm培养皿中,全营养细胞培养基培养24 h,40%~60%融合时转导。shHsp27组/shctrl组中分别加入由1 mL 10倍浓度pLenti-shRNA-Hsp27/pLenti-shRNA-ctrl+5mL全营养细胞培养基+6 µL聚凝胺(8 µg·mL−1)配制的慢病毒转染体系。

3)各组细胞37 °C、5%CO2培养6 h后,更换新鲜全营养培养基,每天换液,24 h后提取总RNA,RT-qPCR检测Hsp27 mRNA表达,72 h后传代。

1.3. RT-qPCR检测体外转染慢病毒颗粒后Hsp27 mRNA的表达

Trizol试剂分别提取各组细胞总RNA,溶于无RNA酶水中,紫外分光光度计测定OD260/OD280在1.8~2.0之间。取1 µg总RNA逆转录合成互补DNA(complementary DNA,cDNA),进行RT-qPCR反应。Hsp27引物序列如下:上游,5′-GTCCCTGGATGTCAACCACT-3′;下游,5′-CTTTACTTGGCGGCAGTCTC-3′。β肌动蛋白引物序列为:上游,5′-GCTCGTCGTCGACAACGGCTC-3′;下游:5′-CAAAACAATGCTCTGGGTCATCTTCT-3′。RT-qPCR反应程序:50 °C 2 min;94 °C 10 min;94 °C 15 s,60 °C 1 min,40个循环。反应结束依据∆∆Ct法计算相对基因表达量。

1.4. 蛋白质印迹检测体外转染慢病毒颗粒后Hsp27蛋白表达

用蛋白抽提试剂盒分别提取各组总蛋白,用BCA蛋白浓度测定试剂盒测定各组蛋白浓度,经十二烷基硫酸钠聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳,将蛋白半干转膜,5%脱脂牛奶封闭20 min,一抗Hsp27/β肌动蛋白单克隆抗体4 °C孵育过夜,TBST缓冲液洗涤3次,辣根过氧化物酶标记的二抗室温孵育1 h,增强化学发光(enhanced chemiluminescence,ECL)法显影。

1.5. MTS细胞增殖实验

MTS细胞增殖实验检测各组细胞培养24、48 h后细胞增殖的变化。将对数生长期的各组细胞接种于96孔板中,全营养DMEM,37 °C,5%CO2培养24、48 h,按照100︰1比例,避光加入MTS/PMS混合试剂每孔25 µL,37 °C、5%CO2培养2.5 h,BioRad550酶标比色仪检测490 nm处的吸光度,每组设3个复孔,取平均值。

1.6. Matrigel体外细胞侵袭实验

检测各组细胞培养40 h后细胞体外侵袭能力的变化。使用无血清1%双抗DMEM细胞悬液将各组细胞接种于自带凝胶化Matrigel基质的上室,下室加入全营养DMEM细胞培养液,37 °C、5%CO2培养40 h后,抹去上室PET膜上表面细胞及Matrigel凝胶后,置于4 °C冷室,用-20 °C保存的甲醇固定10 min,吸弃固定液后,室温下0.5%结晶紫染色,双蒸水洗涤,40倍倒置显微镜下拍照,计数。

1.7. 细胞划痕实验

检测各组划痕产生0、24、48、72 h后细胞体外迁移能力的变化。方法如下:于24孔板中接种每孔2×105,每组设3个复孔,细胞长至60%~80%融合时更换1%双抗无血清培养基,12~18 h后于每孔中央沿直线划痕,磷酸盐缓冲液(phosphate buffered solution,PBS)清洗2次,更换全营养DMEM,荧光显微镜放大40倍拍照,沿细胞划痕自上至下取6~8个测量点,测量划痕宽度。

1.8. 统计学分析

所有实验至少重复3次,采用SPSS 19.0软件统计分析所有数据,所有数值以均值±标准差来表示,组间比较采用t检验,P<0.05记为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. RT-qPCR检测结果

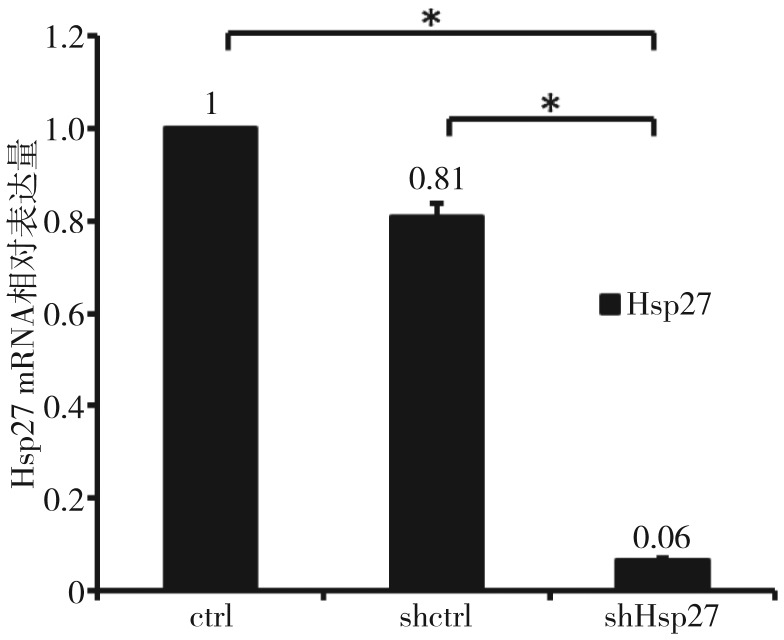

RT-qPCR结果(图1)显示,转染pLenti-shRNA-Hsp27慢病毒颗粒后有效抑制了Hsp27基因的表达。转染24 h后,shHsp27组中Hsp27 mRNA的表达量降至ctrl组的(6±0.56)%,高效沉默了Hsp27基因的表达,两组间的表达差异有统计学意义(P<0.01)。shctrl组中Hsp27 mRNA表达量为ctrl组的(81±6.41)%,几乎不抑制Hsp27基因的表达。shHsp27组与shctrl组相比显著沉默了Hsp27基因的表达(P<0.01)。

图 1. RT-qPCR检测结果.

Fig 1 The result of RT-qPCR

*P<0.01。

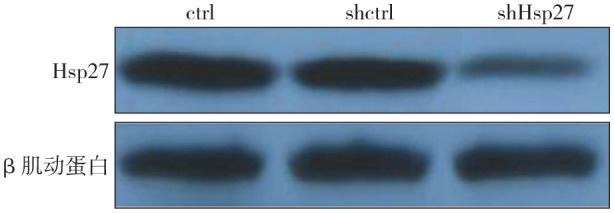

2.2. 蛋白质印迹检测结果

蛋白质印迹检测结果(图2)显示,shHsp27组的Hsp27条带亮度较ctrl组明显降低,shctrl组条带亮度与ctrl组无明显差异。

图 2. 蛋白印迹检测结果.

Fig 2 The result of Western blot

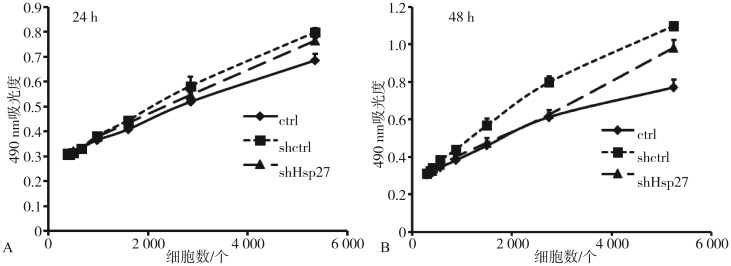

2.3. MTS细胞增殖实验检测结果

MTS细胞增殖实验检测结果(图3)显示,细胞培养24 h后,相同细胞数细胞吸光度值相近,各组细胞增殖分化能力的差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);细胞培养48 h后,shctrl组各细胞数量的细胞增殖能力均高于ctrl组和shHsp27组(P<0.05),shHsp27组在细胞数量较高时,增殖能力高于ctrl组。

图 3. 转染后细胞的增殖曲线.

Fig 3 Proliferation curves of transfected cells

A:24 h;B:48 h。

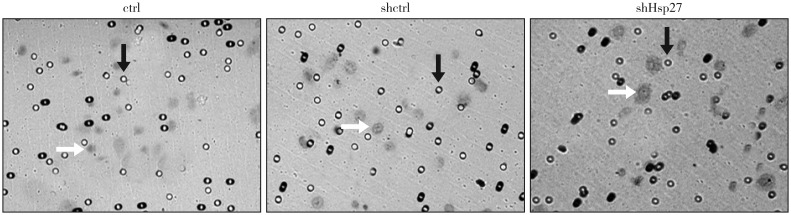

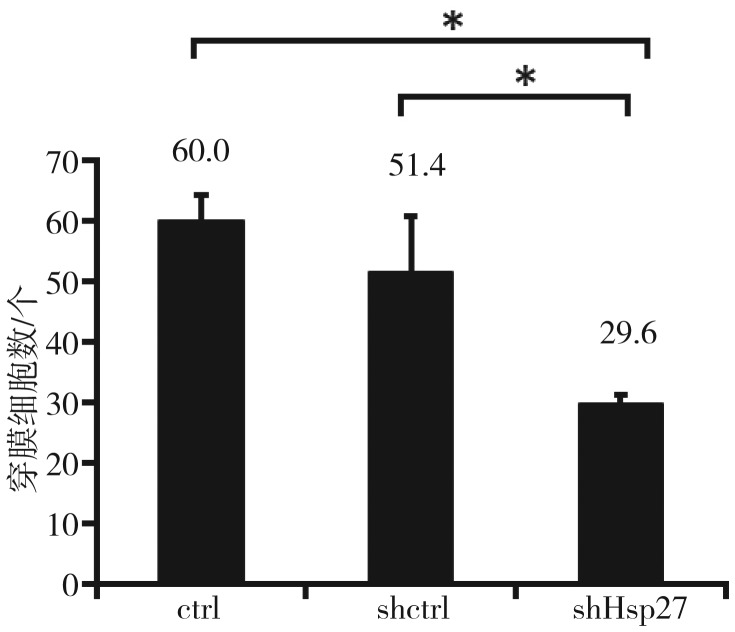

2.4. Matrigel细胞侵袭实验结果

Matrigel细胞侵袭实验结果(图4、5)显示,ctrl组细胞侵袭能力为shHsp27组的2.03倍,shHsp27组的侵袭能力显著降低(P<0.01),即shRNA沉默Hsp27基因后,细胞侵袭能力下降。shctrl组的平均细胞侵袭能力较ctrl组有所下降,shHsp27组与shctrl组相比,侵袭能力显著降低(P<0.01)。

图 4. 转染后细胞的侵袭能力 倒置显微镜 × 40.

Fig 4 Invasion of transfected cells inverteal microscope × 40

左:ctrl组;中:shctrl组;右:shHsp27组。白色箭头:细胞;黑色箭头:侵袭小室膜微孔。

图 5. 细胞侵袭实验穿膜细胞数.

Fig 5 Average cells number of invasion transfected cells

*P<0.01。

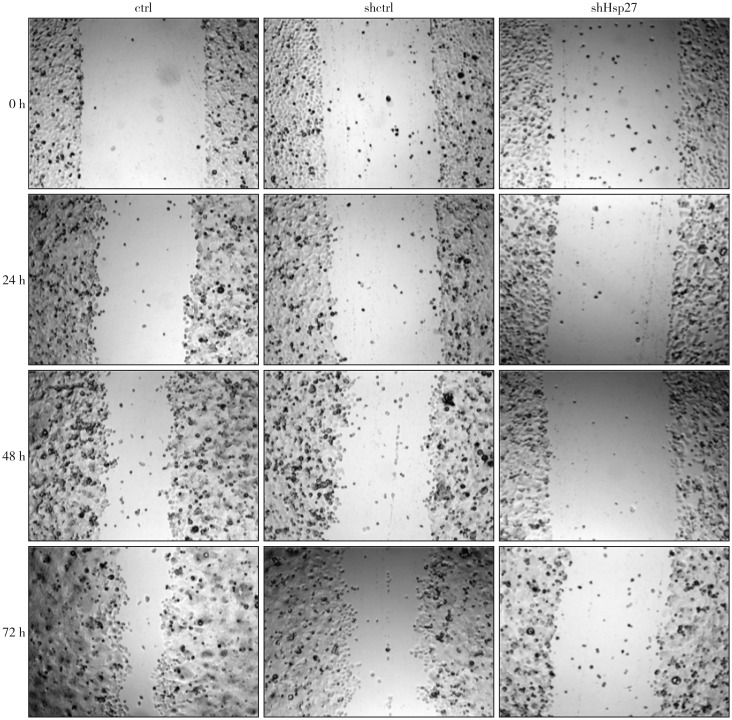

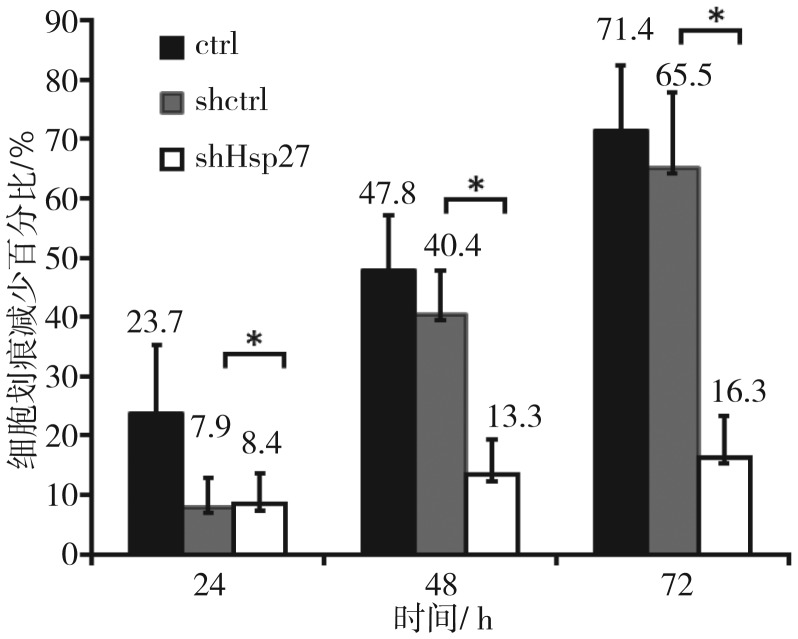

2.5. 细胞划痕实验结果

细胞划痕实验结果(图6、7)显示,划痕产生24 h后,shctrl组与shHsp27组无明显差异(P>0.05);划痕产生48 h后,shctrl组迁移能力有所降低,shHsp27组较shctrl组迁移能力显著降低(P<0.01);划痕产生72 h后,shHsp27组较shctrl组迁移能力显著降低更加明显(P<0.01)。各时间点shHsp27组较ctrl组细胞的迁移能力均显著降低(P<0.01),划痕产生72 h后,ctrl组细胞迁移能力为shHsp27组的4.38倍,即shRNA沉默UM-SCC-22B细胞Hsp27基因后,其体外迁移能力显著降低。

图 6. 细胞划痕实验结果比较 电子显微镜 × 40.

Fig 6 Wound-healing assay results of transfected cells electric microscope × 40

左:ctrl组;中:shctrl组;右:shHsp27组;1~4行依次为划痕产生0、24、48、72 h后。

图 7. 细胞划痕减少百分比的比较.

Fig 7 Wound width reduced of transfected cells

*P>0.01。

3. 讨论

近年来,随着环境污染加剧,吸烟、酗酒等不良生活习惯等因素的影响,恶性肿瘤的发病率呈逐年上升的趋势,头颈部鳞状细胞癌每年约有50万例新发患者。尽管随着医疗技术水平的提高和综合序列治疗等方法的运用,早期头颈部鳞状细胞癌的5年生存率达到了60%,但是其转移病例的术后存活时间仅为6个月[11]–[12],区域性淋巴结转移或远处脏器转移是导致低存活率的主要因素[13]。在原发性实体肿瘤中,只有一小部分肿瘤细胞具备侵袭或转移的能力,高转移潜能细胞与低转移潜能细胞之间的基因表达也不同。因此,如何发现和确定肿瘤转移亚群的标记性基因或蛋白成为研究的热点。

Hsp27作为一种应激蛋白,与多种肿瘤的发生和转移有关,其表达程度与肿瘤分期及预后有一定的相关性。有研究发现,Hsp27在多种肿瘤中呈高表达状态,如前列腺癌[14]、人肝细胞肝癌[15]–[16]、舌鳞状细胞癌[17]、胃癌[18]等,被认为是预后不良的标志性因子。但仍有诸多研究[19]–[20]认为,Hsp27高表达预示着预后良好。不同组织来源的肿瘤、不同病理分型、不同个体间,Hsp27与肿瘤转移和侵袭的关系不完全一致。

因此,为了最大程度地降低个体差异和不同组织来源所造成的结果差异,本研究选取了来自同一患者的原发灶和同期存在的淋巴结转移灶的2种细胞系UM-SCC-22A/UM-SCC-22B,并在前期研究[10]中证实了随着头颈部鳞状细胞癌转移潜能的升高,Hsp27的表达也随之升高。

为了进一步证实Hsp27在头颈部鳞状细胞癌转移中的作用,本研究采用了基因工程技术,将能够稳定表达Hsp27 shRNA的慢病毒载体转染入高转移潜能头颈部鳞状细胞癌UM-SCC-22B细胞系中,通过体内外实验观察Hsp27基因与UM-SCC-22B迁移和侵袭能力的关系。

经RT-qPCR和蛋白印迹检测,高效、特异地沉默了Hsp27基因的表达,通过MTS细胞增殖实验、细胞划痕实验、Matrigel细胞侵袭实验,证实了长效转染shRNA Hsp27慢病毒后,UM-SCC-22B的体外转移能力明显下降。其中,MTS细胞增殖实验发现,shctrl组的增殖能力增强,目前虽无理论依据揭示其原因,但此现象揭示了细胞划痕实验和Matrigel细胞侵袭实验的差异性结果并非由细胞增殖能力差异引起,而shHsp27组细胞增殖能力增强的同时侵袭和迁移能力降低,更进一步说明沉默Hsp27基因后,有效抑制了UM-SCC-22B的转移。

综上所述,本研究结果表明,长效转染慢病毒颗粒pLenti-shRNA-Hsp27能够高效、特异地沉默高转移潜能头颈部鳞状细胞癌细胞系UM-SCC-22B的Hsp27基因的表达,并能显著抑制其体外侵袭转移能力。

Funding Statement

[基金项目] 泰山学者建设项目专项基金(ts201511106);山东大学交叉学科项目(2016JC024)

Supported by: Shandong Taishan Scholar Project Special Fund (ts201511106); Interdisciplinary Program of Shandong University (2016JC024).

Footnotes

利益冲突声明:作者声明本文无利益冲突。

References

- 1.Muschter D, Geyer F, Bauer R, et al. A comparison of cell survival and heat shock protein expression after radiation in normal dermal fibroblasts, microvascular endothelial cells, and different head and neck squamous carcinoma cell lines[J] Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22(6):2251–2262. doi: 10.1007/s00784-017-2323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ginos MA, Page GP, Michalowicz BS, et al. Identification of a gene expression signature associated with recurrent disease in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck[J] Cancer Res. 2004;64(1):55–63. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werner JA, Rathcke IO, Mandic R. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck[J] Clin Exp Metastasis. 2002;19(4):275–282. doi: 10.1023/a:1015531319087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freilich R, Betegon M, Tse E, et al. Competing protein-protein interactions regulate binding of Hsp27 to its client protein tau[J] Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4563. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duprez F, Berwouts D, De Neve W, et al. Distant metastases in head and neck cancer[J] Head Neck. 2017;39(9):1733–1743. doi: 10.1002/hed.24687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acunzo J, Andrieu C, Baylot V, et al. Hsp27 as a therapeutic target in cancers[J] Curr Drug Targets. 2014;15(4):423–431. doi: 10.2174/13894501113146660230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Ommeren R, Staudt MD, Xu H, et al. Advances in HSP27 and HSP90-targeting strategies for glioblastoma[J] J Neurooncol. 2016;127(2):209–219. doi: 10.1007/s11060-016-2070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berrieman HK, Cawkwell L, O'Kane SL, et al. Hsp27 may allow prediction of the response to single-agent vinorelbine chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer[J] Oncol Rep. 2006;15(1):283–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarto C, Valsecchi C, Magni F, et al. Expression of heat shock protein 27 in human renal cell carcinoma[J] Proteomics. 2004;4(8):2252–2260. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu Z, Xu X, Yu Y, et al. Silencing heat shock protein 27 decreases metastatic behavior of human head and neck squamous cell cancer cells in vitro[J] Mol Pharm. 2010;7(4):1283–1290. doi: 10.1021/mp100073s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farkona S, Diamandis EP, Blasutig IM. Cancer immunotherapy: the beginning of the end of cancer[J] BMC Med. 2016;14:73. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0623-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012[J] CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alvarez Marcos CA, Llorente Pendás JL, Franco Gutiérrez V, et al. Distant metastases in head and neck cancer[J] Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2006;57(8):369–372. doi: 10.1016/s0001-6519(06)78730-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albany C, Hahn NM. Heat shock and other apoptosis-related proteins as therapeutic targets in prostate cancer[J] Asian J Androl. 2014;16(3):359–363. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.126400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eto D, Hisaka T, Horiuchi H, et al. Expression of HSP27 in hepatocellular carcinoma[J] Anticancer Res. 2016;36(7):3775–3779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang C, Zhang Y, Guo K, et al. Heat shock proteins in hepatocellular carcinoma: molecular mechanism and therapeutic potential[J] Int J Cancer. 2016;138(8):1824–1834. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohtasham N, Babakoohi S, Montaser-Kouhsari L, et al. The expression of heat shock proteins 27 and 105 in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue and relationship with clinicopathological index[J] Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011;16(6):e730–e735. doi: 10.4317/medoral.17007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ge H, He X, Guo L, et al. Clinicopathological significance of HSP27 in gastric cancer: a meta-analysis[J] Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:4543–4551. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S146590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thanner F, Sütterlin MW, Kapp M, et al. Heat shock protein 27 is associated with decreased survival in node-negative breast cancer patients[J] Anticancer Res. 2005;25(3A):1649–1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishitsuji H, Ikeda T, Miyoshi H, et al. Expression of small hairpin RNA by lentivirus-based vector confers efficient and stable gene-suppression of HIV-1 on human cells including primary non-dividing cells[J] Microbes Infect. 2004;6(1):76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]