Abstract

目的

对骨支抗装置与上颌面具前牵引装置治疗青少年骨性Ⅲ类错 畸形的临床效果进行系统评价。

畸形的临床效果进行系统评价。

方法

检索Cochrane Library、PubMed、EmBase、CNKI、万方等数据库,查找种植支抗装置与上颌面具前牵引装置治疗青少年骨性Ⅲ类错 临床效果的文献,对文献进行筛选、提取资料及质量评价。应用RevMan 5.3软件进行统计,对2种方法治疗前后SNA、SNB、ANB、ANS-Me、Wits和U1-PP的变化值进行Meta分析。

临床效果的文献,对文献进行筛选、提取资料及质量评价。应用RevMan 5.3软件进行统计,对2种方法治疗前后SNA、SNB、ANB、ANS-Me、Wits和U1-PP的变化值进行Meta分析。

结果

研究最终纳入7篇文献,其中3篇随机对照试验,4篇非随机对照试验,共纳入264例患者。Meta分析结果显示,骨支抗治疗组较上颌面具前牵引组SNA变化值增加,ANS-Me、Wits、U1-PP变化值减小(P<0.05),SNB、ANB变化值2组之间无统计学差异。

结论

骨支抗装置与上颌面具前牵引装置治疗青少年骨性Ⅲ类错 相比,可以增加上颌骨的前移量,并较好地控制上颌前牙的唇倾度,但结果仍然需要更多的高质量随机对照试验进行验证。

相比,可以增加上颌骨的前移量,并较好地控制上颌前牙的唇倾度,但结果仍然需要更多的高质量随机对照试验进行验证。

Keywords: 骨支抗, 前牵引, 青少年, 骨性Ⅲ类错|HE|, Meta分析

Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy of bone anchorage and maxillary facemask protraction devices in treating skeletal class Ⅲ malocclusion in adolescents.

Methods

Articles relating to the use of bone anchorage and maxillary facemask protraction devices for treating skeletal class Ⅲ malocclusion in adolescents were searched from the databases of Cochrane Library, PubMed, EmBase, CNKI, and Wanfang database. Several inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed for the article screening. The clinical data were extracted, and the quality of the selected articles was evaluated. A Meta-analysis of SNA, SNB, ANB, ANS-Me, Wits, and U1-PP change was performed by using RevMan 5.3.

Results

Seven studies (264 patients) were included in the Meta-analysis. Among these studies, three were randomized controlled trials, and four were non-randomized controlled trials. Compared with the maxillary facemask protraction device group, the bone anchorage device group had higher SNA changes and lower ANS-Me, Wits, and U1-PP changes (P<0.05). No significant differences were observed in the SNB and ANB changes between these two groups.

Conclusion

Compared with the maxillary facemask protraction device, the bone anchorage device can increase the extent of protraction of the maxilla and has better controls for the labial inclination of the maxillary anterior teeth in treating skeletal class Ⅲ malocclusion among adolescents. However, additional high-quality randomized controlled trials must be performed to verify the results.

Keywords: bone anchorage, protraction, adolescents, skeletal class Ⅲ malocclusion, Meta-analysis

骨性Ⅲ类错 畸形是临床中较难处理的问题,主要表现为面中份凹陷、上颌骨发育不足和(或)下颌骨发育过度[1],由于其特有的临床特征,随着年龄增长,畸形日趋严重,不仅会造成面中部凹陷、上颌后缩和下颌前凸等面部畸形,而且还会影响儿童的心理发育,同时也会引起咀嚼和语言等功能障碍。Ellis等[2]发现65%~67%的骨性Ⅲ类错

畸形是临床中较难处理的问题,主要表现为面中份凹陷、上颌骨发育不足和(或)下颌骨发育过度[1],由于其特有的临床特征,随着年龄增长,畸形日趋严重,不仅会造成面中部凹陷、上颌后缩和下颌前凸等面部畸形,而且还会影响儿童的心理发育,同时也会引起咀嚼和语言等功能障碍。Ellis等[2]发现65%~67%的骨性Ⅲ类错 以上颌骨发育不足为特征,因此大多数治疗模式依赖于上颌前牵引。上颌前牵引的原理是直接在上颌骨缝间施加向前的力,从而刺激青少年早期上颌骨的发育。通过上颌面具前牵引装置(牙支持式矫治器)将矫形力传递至上颌骨是传统的青少年骨性Ⅲ类错

以上颌骨发育不足为特征,因此大多数治疗模式依赖于上颌前牵引。上颌前牵引的原理是直接在上颌骨缝间施加向前的力,从而刺激青少年早期上颌骨的发育。通过上颌面具前牵引装置(牙支持式矫治器)将矫形力传递至上颌骨是传统的青少年骨性Ⅲ类错 治疗方法[3]–[4]。近年来开始较多的运用骨支抗装置(种植体)进行治疗,研究表明骨支抗干预方式能获得较多的骨效应和较小的牙效应[5]–[16]。本文对骨支抗装置和上颌面具前牵引装置治疗青少年骨性Ⅲ类错

治疗方法[3]–[4]。近年来开始较多的运用骨支抗装置(种植体)进行治疗,研究表明骨支抗干预方式能获得较多的骨效应和较小的牙效应[5]–[16]。本文对骨支抗装置和上颌面具前牵引装置治疗青少年骨性Ⅲ类错 畸形的矫治效果进行Meta分析,为临床应用提供依据。

畸形的矫治效果进行Meta分析,为临床应用提供依据。

1. 材料和方法

1.1. 研究的纳入和排除标准

1.1.1. 研究的纳入标准

纳入标准如下。

研究对象:1)文献明确提及试验者为符合骨性安氏Ⅲ类错 畸形诊断标准[17]需进行正畸治疗的青少年(年龄<15岁);2)正畸治疗中需利用种植支抗或传统的上颌面具前牵引装置进行上颌前牵引;3)无先天性缺失牙齿(第三磨牙除外),无不良习惯及正畸治疗史,无牙周病及系统性疾病;无唇(腭)裂;4)有相关头颅侧位片测量分析指标的数据。

畸形诊断标准[17]需进行正畸治疗的青少年(年龄<15岁);2)正畸治疗中需利用种植支抗或传统的上颌面具前牵引装置进行上颌前牵引;3)无先天性缺失牙齿(第三磨牙除外),无不良习惯及正畸治疗史,无牙周病及系统性疾病;无唇(腭)裂;4)有相关头颅侧位片测量分析指标的数据。

研究类型:骨支抗与上颌面具装置行上颌前牵引的对照试验;至少包含治疗前、后头颅侧位片指标分析对比的随机对照试验及病例对照试验;语种限中英文。

干预措施:骨支抗组(BA组)采用种植支抗治疗,传统方法组(对照组)采用上颌面具前牵引(包含或不包含扩弓)治疗。

结局指标:主要结局指标为骨支抗组和传统方法组治疗前后SNA、SNB和ANB的变化值;次要结局指标为2组治疗前后ANS-Me、Wits和U1-PP的变化值。统计指标为MD及其95%可信区间。

1.1.2. 研究的排除标准

1)同一研究中心同一批次数据多次发表,或者发表数据在不同文献中重叠交叉;2)病例报告、综述、调查问卷、书信和会议记录、动物实验、材料学研究、模型研究和相关基础研究;3)文献为非对照文献;4)安氏Ⅲ类错 畸形患者传统固定矫正的治疗研究。

畸形患者传统固定矫正的治疗研究。

1.2. 检索策略

检索Cochrane Library、PubMed、EmBase,检索主题词为:class Ⅲ malocclusion、extraoral traction appliances、orthodontic anchorage procedures及其相关所有自由词;检索CNKI、万方数据库,检索词为上颌前牵引、骨支抗、种植体牵引、Ⅲ类错 。检索时间从建库至2018年4月。

。检索时间从建库至2018年4月。

1.3. 资料提取及质量评价

由2位评价员独立严格按照纳入与排除标准筛选文献,提取资料,制成评价表,并交叉核对,确认结果一致性,通过协商或第3位研究者解决分歧。通过对评价员之间的一致性检验,Kappa值为0.9,2位评价员对文献评估的一致性较好。资料提取的内容包括:作者、出版年限、实验设计、研究对象的基本资料、样本量、相关结局指标。采用Cochrane协作网系统评价手册5.1.0推荐的质量评价方法对随机对照试验进行方法学质量评价[18],采用Newcastle-Ottawa Scale(NOS)文献质量评估量表对非随机对照试验进行质量评价[19]。

1.4. 统计学处理

采用RevMan 5.3软件进行统计分析。连续变量资料采用均数差(mean difference,MD)及其95%可信区间(confidence intervals,CI)表示。P<0.05为差异具有统计学意义。各研究结果间的异质性采用χ2检验。若无明显异质性(P≥0.1,I2≤50%),采用固定效应模型进行Meta分析;若存在明显异质性(P<0.1,I2>50%),则采用随机效应模型。通过逐一剔除每项研究后观察剩余研究的效应合并量进行敏感性分析。对有潜在性的发表偏倚采用漏斗图表示。

2. 结果

2.1. 检索结果

初检出相关文献668篇,经阅读文章题目和摘要筛选出15篇,阅读全文排除未达到纳入标准的8篇,最终纳入7篇文献[6]–[7],[20]–[24]。其中随机对照试验3篇[20]–[22],非随机对照试验4篇[6]–[7],[23]–[24]。研究中包含264例患者,其中使用骨支抗者126例,使用上颌面具者138例;其中样本量最大的为55例,最小的为20例。纳入研究的基本特征见表1。

表 1. 纳入研究的基本特征.

Tab 1 Characteristics of included studies

| 作者及发表年 | 样本量 |

年龄/岁 |

性别(男/女) |

结局指标 | 研究设计方案 | |||

| 骨支抗组 | 传统方法组 | 骨支抗组 | 传统方法组 | 骨支抗组 | 传统方法组 | |||

| Aglarci 2016[20] | 25 | 25 | 11.75±1.23 | 11.21±1.32 | 12/13 | 12/13 | A、B、C、D、E、F | 随机对照试验 |

| Jamilian 2011[21] | 10 | 10 | 11.3±0.8 | 10.5±1.5 | 5/5 | 3/7 | A、B、C、F | 随机对照试验 |

| Cevidanes 2010[6] | 21 | 34 | 11.83±1.83 | 8.25±1.83 | 10/11 | 14/20 | D、E、F | 病例对照试验,回顾性 |

| Ge 2012[22] | 25 | 24 | 10.33 | 10.5 | 11/14 | 12/12 | A、B、C、E | 随机对照试验 |

| Lee 2012[23] | 10 | 10 | 11.2±1.2 | 10.7±1.3 | 5/5 | 6/4 | A、B、C、E | 病例对照试验,回顾性 |

| Ngan 2015[7] | 20 | 20 | 9.8±1.2 | 9.7±16 | 8/12 | 8/12 | A、B、C、E | 病例对照试验,回顾性 |

| Sar 2011[24] | 15 | 15 | 10.91 | 10.31 | 10/5 | 8/7 | A、B、C、D、E、F | 病例对照试验,回顾性 |

注:结局指标中,A为SNA角,B为SNB角,C为ANB角,D为ANS-Me,E为Wits角,F为U1-PP。

2.2. 方法学质量评价

7篇文献中均未行盲法评估,不同程度地提及了研究对象的特性、基线方法、混杂因素的排除、随访率等,质量评价等级均为A。

2.3. Meta分析结果

2.3.1. SNA变化

6篇文献[7],[20]–[24]分析了SNA的变化情况。异质性分析提示组间无明显异质性(P=0.51,I2=0%),采用固定效应模型。结果(图1)显示,骨支抗组SNA变化值较传统方法组增加0.53°[MD=0.53,95%CI(0.13,0.94),P=0.01]。

图 1. 2组治疗前后SNA变化值比较的Meta分析.

Fig 1 Meta-analysis of the changes of SNA before and after treatment in 2 groups

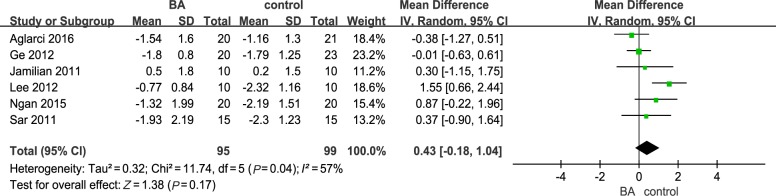

2.3.2. SNB变化

6篇文献[7],[20]–[24]分析了SNB的变化情况。异质性分析提示组间存在异质性(P=0.04,I2=57%),采用随机效应模型。不论是否剔除异质性来源Lee 2012[23],骨支抗组SNB变化值与传统方法组均无明显差异[未剔除时,MD=0.43,95%CI(−0.18,1.04),P=0.17,I2=57%(图2);剔除后,MD=0.10,95%CI(−0.31,0.52),P=0.63,I2=0%]。

图 2. 2组治疗前后SNB变化值比较的Meta分析.

Fig 2 Meta-analysis of the changes of SNB before and after treatment in 2 groups

2.3.3. ANB变化

6篇文献[7],[20]–[24]分析了ANB的变化情况。异质性分析提示组间无异质性(P=0.96,I2=0%),采用固定效应模型。结果(图3)显示,骨支抗组ANB变化值与传统方法组无明显差异[MD=0.23,95%CI(−0.22,0.68),P=0.31]。

图 3. 2组治疗前后ANB变化值比较的Meta分析.

Fig 3 Meta-analysis of the changes of ANB before and after treatment in 2 groups

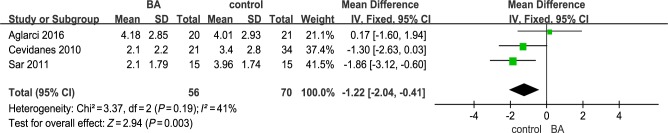

2.3.4. ANS-Me变化

3篇文献[6],[20],[24]分析了ANS-Me的变化情况。异质性分析提示组间无明显异质性(P=0.19,I2=41%),采用固定效应模型。结果(图4)显示,骨支抗组ANS-Me变化值较传统方法组减少1.22 mm[MD=−1.22,95%CI(−2.04,−0.41),P=0.003]。

图 4. 2组治疗前后ANS-Me变化值比较的Meta分析.

Fig 4 Meta-analysis of the changes of ANS-Me before and after treatment in 2 groups

2.3.5. Wits变化

6篇文献[6]–[7],[20],[22]–[24]分析了Wits值的变化。异质性分析提示组间存在异质性(P=0.000 4,I2=78%),采用随机效应模型。未剔除异质性来源时,骨支抗组Wits变化值与传统方法组无明显差异[MD=−0.26,95%CI(−1.65,1.14),P=0.72,I2=78%](图5);剔除异质性来源Cevidanes 2010[6]后,骨支抗组变化值较传统方法组减小0.8 mm[MD=0.8,95%CI(−1.57,−0.03),P=0.04,I2=0%]。

图 5. 2组治疗前后Wits变化值比较的Meta分析.

Fig 5 Meta-analysis of the changes of Wits before and after treatment in 2 groups

2.3.6. U1-PP变化

4篇文献[6],[20]–[21],[24]分析了以U1-PP的变化情况。异质性分析提示组间无明显异质性(P=0.23,I2=30%),采用固定效应模型。结果(图6)显示,骨支抗组U1-PP变化值较传统方法组减小0.43°[MD=-0.43,95%CI(−0.76,−0.09),P=0.01]。

图 6. 2组治疗前后U1-PP变化值比较的Meta分析.

Fig 6 Meta-analysis of the changes of U1-PP before and after treatment in 2 groups

2.4. 发表偏倚

对主要结局指标SNA、SNB、ANB制定漏斗图,漏斗图基本对称,提示无发表性偏倚。

3. 讨论

上颌前牵引的目的在于刺激上颌骨生长,从而达到矫治上下颌骨关系不调的目的。相对传统面罩前牵引,在前颌骨或颧牙槽嵴下方植入微小钛板或种植钉,能够取得患者更好的临床配合,牵引方向接近或通过上颌牙弓以及上颌复合体的阻力中心,使其产生平动,从而接近理想的移动状态[25]–[26]。本研究Meta分析结果提示,A点前移量在骨支抗组较传统治疗组增加,SNA变化值增加,而SNB、ANB变化值无统计学差异。

研究[27]–[29]表明,传统牙支持式面具前牵引治疗过程中,会产生唇倾上前牙的副作用。本研究Meta分析结果显示,骨支抗组U1-PP变化值较传统前牵引组小,这与骨支抗对上颌牙弓的移动方式更接近于整体移动有关,会产生较多的骨效应和较少的牙效应。治疗前后骨支抗组较传统前牵引组Wits变化值减小,提示骨支抗组与传统前牵引组相比, 平面发生顺时针方向旋转。

平面发生顺时针方向旋转。

目前关于骨支抗治疗青少年骨性Ⅲ类错 畸形的研究中,多数是将未治疗患者设置为对照组,而未将传统矫治方式设置为对照组,因此本研究纳入文献量较少,只有7项研究,样本量只有264例患者,使研究结果具有一定的局限性,今后尚需更多高质量的随机对照试验进行验证。

畸形的研究中,多数是将未治疗患者设置为对照组,而未将传统矫治方式设置为对照组,因此本研究纳入文献量较少,只有7项研究,样本量只有264例患者,使研究结果具有一定的局限性,今后尚需更多高质量的随机对照试验进行验证。

Footnotes

利益冲突声明:作者声明本文无利益冲突。

References

- 1.Liou EJ. Effective maxillary orthopedic protraction for growing Class Ⅲ patients: a clinical application simulates distraction osteogenesis[J] Prog Orthod. 2005;6(2):154–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis E, 3rd, McNamara JA., Jr Components of adult Class Ⅲ malocclusion[J] J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;42(5):295–305. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(84)90109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

3.徐 宝华. 骨性前牙反

的前方牵引治疗[J] 口腔正畸学. 2001;8(3):133–135. [Google Scholar]; Xu BH. The orthopedic treatment of skeletal class Ⅲ malocclusion with maxillary protraction therapy[J] Chin J Orthod. 2001;8(3):133–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

的前方牵引治疗[J] 口腔正畸学. 2001;8(3):133–135. [Google Scholar]; Xu BH. The orthopedic treatment of skeletal class Ⅲ malocclusion with maxillary protraction therapy[J] Chin J Orthod. 2001;8(3):133–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.庄 金良, 李 勋, 姜 雨君, et al. 应用Coben分析法评价前方牵引治疗上颌发育不足的临床疗效[J] 华西口腔医学杂志. 2015;33(1):58–62. doi: 10.7518/hxkq.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zhuang JL, Li X, Jiang YJ, et al. Using Coben analysis to evaluate the therapeutic effect of maxillary protraction on maxillary maldevelopment[J] West China J Stomatol. 2015;33(1):58–62. doi: 10.7518/hxkq.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Clerck HJ, Proffit WR. Growth modification of the face: a current perspective with emphasis on Class Ⅲ treatment[J] Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2015;148(1):37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cevidanes L, Baccetti T, Franchi L, et al. Comparison of two protocols for maxillary protraction: bone anchors versus face mask with rapid maxillary expansion[J] Angle Orthod. 2010;80(5):799–806. doi: 10.2319/111709-651.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ngan P, Wilmes B, Drescher D, et al. Comparison of two maxillary protraction protocols: tooth-borne versus bone-anchored protraction facemask treatment[J] Prog Orthod. 2015;16:26. doi: 10.1186/s40510-015-0096-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodríguez de Guzmán-Barrera J, Sáez Martínez C, Boronat-Catalá M, et al. Effectiveness of interceptive treatment of class Ⅲ malocclusions with skeletal anchorage: a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J] PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bozkaya E, Yüksel AS, Bozkaya S. Zygomatic miniplates for skeletal anchorage in orthopedic correction of Class Ⅲ malocclusion: a controlled clinical trial[J] Korean J Orthod. 2017;47(2):118–129. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2017.47.2.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong H, Ngan P, Han GL, et al. Use of onplants as stable anchorage for facemask treatment: a case report[J] Angle Orthod. 2005;75(3):453–460. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2005)75[453:UOOASA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jamilian A, Showkatbakhsh R. Treatment of maxillary deficiency by miniscrew implants—a case report[J] J Orthod. 2010;37(1):56–61. doi: 10.1179/14653121042876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.王 晓誉, 贺 佳. 骨种植钉上颌前牵引和支架上颌牵引的比较研究[J] 齐齐哈尔医学院学报. 2014;35(24):3600–3601. [Google Scholar]; Wang XY, He J. Comparison of two protocols for maxillary protraction: bone anchors versus face mask[J] J Qiqihar Univ Med. 2014;35(24):3600–3601. [Google Scholar]

-

13.亢 静, 彭 明慧. 种植支抗前牵引矫治儿童骨性Ⅲ类错

后硬软组织变化的临床研究[J] 实用口腔医学杂志. 2017;33(3):349–353. [Google Scholar]; Kang J, Peng MH. Analysis of the profile esthetics of children with skeletal class Ⅲ malocclusion treated with micro-implant[J] J Pract Stomatol. 2017;33(3):349–353. [Google Scholar]

后硬软组织变化的临床研究[J] 实用口腔医学杂志. 2017;33(3):349–353. [Google Scholar]; Kang J, Peng MH. Analysis of the profile esthetics of children with skeletal class Ⅲ malocclusion treated with micro-implant[J] J Pract Stomatol. 2017;33(3):349–353. [Google Scholar]

- 14.李 建华, 封 小霞, 杨 璞. 骨支抗前牵引的研究进展[J] 国际口腔医学杂志. 2013;40(3):416–418. [Google Scholar]; Li JH, Feng XX, Yang P. Research progress on the bone-anchored maxillary protraction[J] Int J Stomatol. 2013;40(3):416–418. [Google Scholar]

-

15.孟 耀, 刘 进, 郭 鑫, et al. 骨种植钉前牵引对骨性Ⅲ类错

患者软硬组织侧貌的影响[J] 华西口腔医学杂志. 2012;30(3):278–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Meng Y, Liu J, Guo X, et al. Soft and hard tissue changes after maxillary protraction with skeletal anchorage implant in treatment of Class Ⅲ malocclusion[J] West China J Stomatol. 2012;30(3):278–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

患者软硬组织侧貌的影响[J] 华西口腔医学杂志. 2012;30(3):278–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Meng Y, Liu J, Guo X, et al. Soft and hard tissue changes after maxillary protraction with skeletal anchorage implant in treatment of Class Ⅲ malocclusion[J] West China J Stomatol. 2012;30(3):278–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyns J, Brasil DM, Mazzi-Chaves JF, et al. The clinical outcome of skeletal anchorage in interceptive treatment (in growing patients) for class Ⅲ malocclusion[J] Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;47(8):1003–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baccetti T, McGill JS, Franchi L, et al. Skeletal effects of early treatment of Class Ⅲ malocclusion with maxillary expansion and face-mask therapy[J] Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1998;113(3):333–343. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70306-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Obrador GT, Villa AR, Olvera N, et al. Longitudinal analysis of participants in the KEEP Mexico's chronic kidney disease screening program[J] Arch Med Res. 2013;44(8):650–654. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in Meta-analyses[J] Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aglarci C, Esenlik E, Findik Y. Comparison of short-term effects between face mask and skeletal anchorage therapy with intermaxillary elastics in patients with maxillary retrognathia[J] Eur J Orthod. 2016;38(3):313–323. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjv053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jamilian A, Haraji A, Showkatbakhsh R, et al. The effects of miniscrew with Class Ⅲ traction in growing patients with maxillary deficiency[J] Int J Orthod Milwaukee. 2011;22(2):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ge YS, Liu J, Chen L, et al. Dentofacial effects of two facemask therapies for maxillary protraction[J] Angle Orthod. 2012;82(6):1083–1091. doi: 10.2319/012912-76.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee NK, Yang IH, Baek SH. The short-term treatment effects of face mask therapy in Class Ⅲ patients based on the anchorage device: miniplates vs rapid maxillary expansion[J] Angle Orthod. 2012;82(5):846–852. doi: 10.2319/090811-584.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sar C, Arman-Özçırpıcı A, Uçkan S, et al. Comparative evaluation of maxillary protraction with or without skeletal anchorage[J] Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2011;139(5):636–649. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.赵 志河, 赵 美英. 上颌复合体及上颌牙弓阻力中心位置的研究[J] 口腔正畸学. 1994;1(1):25–26. [Google Scholar]; Zhao ZH, Zhao MY. The study of maxillary complex and the position of maxillary arch resistance center[J] Chin J Orthod. 1994;1(1):25–26. [Google Scholar]

- 26.周 彦恒, 丁 鹏, 林 野, et al. 钛板种植体上颌前方牵引治疗的初步应用研究[J] 口腔正畸学. 2007;14(3):102–105. [Google Scholar]; Zhou YH, Ding P, Lin Y, et al. Preliminary study on miniplate implant anchorage for maxillary protraction[J] Chin J Orthod. 2007;14(3):102–105. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mermigos J, Full CA, Andreasen G. Protraction of the maxillofacial complex[J] Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1990;98(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(90)70031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saadia M, Torres E. Sagittal changes after maxillary protraction with expansion in class Ⅲ patients in the primary, mixed, and late mixed dentitions: a longitudinal retrospective study[J] Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2000;117(6):669–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takada K, Petdachai S, Sakuda M. Changes in dentofacial morphology in skeletal Class Ⅲ children treated by a modified maxillary protraction headgear and a chin cup: a longitudinal cephalometric appraisal[J] Eur J Orthod. 1993;15(3):211–221. doi: 10.1093/ejo/15.3.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

畸形疗效比较的Meta分析

畸形疗效比较的Meta分析