Abstract

Background

Injury is responsible for an increasing global burden of death and disability. As a result, new models of trauma care have been developed. Many of these, though initially developed in high‐income countries (HICs), are now being adopted in low and middle‐income countries (LMICs). One such trauma care model is advanced trauma life support (ATLS) training in hospitals, which is being promoted in LMICs as a strategy for improving outcomes for victims of trauma. The impact of this health service intervention, however, has not been rigorously tested by means of a systematic review in either HIC or LMIC settings.

Objectives

To quantify the impact of ATLS training for hospital staff on injury mortality and morbidity in hospitals with and without such a training program.

Search methods

The search for studies was run on the 16th May 2014. We searched the Cochrane Injuries Group's Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library), Ovid MEDLINE(R), Ovid MEDLINE(R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid OLDMEDLINE(R), Embase Classic+Embase (Ovid), ISI WOS (SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, CPCI‐S & CPSI‐SSH), CINAHL Plus (EBSCO), PubMed and screened reference lists.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials, controlled trials and controlled before‐and‐after studies comparing the impact of ATLS‐trained hospital staff versus non‐ATLS trained hospital staff on injury mortality and morbidity.

Data collection and analysis

Three authors applied the eligibility criteria to trial reports for inclusion, and extracted data.

Main results

None of the studies identified by the search met the inclusion criteria for this review.

Authors' conclusions

There is no evidence from controlled trials that ATLS or similar programs impact the outcome for victims of injury, although there is some evidence that educational initiatives improve knowledge of hospital staff of available emergency interventions. Furthermore, there is no evidence that trauma management systems that incorporate ATLS training impact positively on outcome. Future research should concentrate on the evaluation of trauma systems incorporating ATLS, both within hospitals and at the health system level, by using more rigorous research designs.

Plain language summary

Advanced training in trauma life support for hospital staff

Training in 'advanced trauma life support' (ATLS) is increasingly used in both rich and poor countries. ATLS is intended to improve the way in which care is given to injured people, thereby reducing death and disability. Some research has been done that suggests ATLS programmes improve the knowledge of staff who have been trained, but there have been no controlled trials to show the impact of ATLS‐trained staff (or staff trained in similar programmes) on the rates of death and disability of injured patients themselves. The review calls for more research and puts forward suggestions about how future research might be conducted.

Background

The Global Burden of Disease Study has repeatedly identified injuries as one of the top ten causes of death and disability worldwide (Murray 1997a; Murray 1997b; Murray 1997c; Lopez 2006). Injury is predicted to rise in the rankings by the year 2030 (Mathers 2006). While infectious diseases continue to be extremely important causes of death in low and middle‐income countries (LMICs), there are increasing challenges posed by injury and non‐communicable disease for premature mortality and morbidity globally (Gwatkin 1997). Injuries place a disproportionately large burden of disease on young people, causing premature loss of productive life, high medical care costs, significant degrees of disability, and a large socio‐economic loss to society (WHO 2004).

Recently there have been calls by the public health community, professional associations and nongovernmental organisations for the formulation of a strategy to decrease the social burden from injuries. Responding to injuries requires considerable attention to preventive efforts (Berger 1996), as well as improvements in healthcare provision to reduce deaths, disability and costs to society (Sethi 2000). In many high‐income countries (HICs), reductions in trauma mortality of 15‐20% have been achieved in the last few decades (Cales 1984; Lecky 2000; Roberts 1996), largely as a result of improved healthcare interventions and trauma care systems. Training programmes such as Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) established by the American College of Surgeons and introduced in North America, the United Kingdom and Australia, have presumably contributed to this reduction (Kirsch 1998; Reines 1988). Improvement in the organisation and delivery of trauma services, with ATLS‐trained staff acting as co‐ordinated trauma response teams, are thought to improve the timing and quality of the emergency response in the 'golden hour' (Calicott 1980), specifically through the appropriate use of acute interventions such as fluid replacement, endotracheal intubation, chest drainage and emergency surgery.

However, the evidence of effectiveness and impact of ATLS has not been rigorously tested for either HIC and or LMIC settings. Currently, the evidence base for trauma services in LMICs is almost non‐existent. Yet, despite this lack of evidence, the ATLS system is being promoted as a model for improving outcomes for trauma victims in LMICs (Ali 1994). In resource‐constrained settings, models of trauma care developed in HICs need to be considered carefully based on effectiveness, affordability and appropriateness before they can be recommended for implementation in LMICs (Sethi 2000). One way of ensuring that trauma care interventions add value for money is to evaluate the evidence of supporting their effectiveness and impact. A previous systematic review has examined ATLS interventions in the pre‐hospital setting (Jayaraman 2014). This review seeks to evaluate the impact of hospital‐based ATLS training programmes on injury mortality and morbidity.

Why it is important to do this review

The aim of this systematic review is to quantify the effectiveness of an ATLS (or equivalent) programme in improving the trauma outcomes of mortality and disability.

Objectives

To quantify the impact of hospital‐based ATLS training for medical staff on injury mortality and morbidity in hospitals with and without such training programs.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Eligible trials will include randomised controlled trials (RCTs), controlled trials (CTs), and controlled before‐and‐after (CBA) studies, each of which is defined as follows. RCT: a study involving at least one intervention and one control treatment, with concurrent enrolment and follow up of the intervention and control groups, in which the interventions to be tested are selected by a random process such as the use of a random numbers table (coin flips are also acceptable). If the author(s) state explicitly (usually by using some variant of the term 'random' to describe the allocation procedure used) that the groups compared in the trial were established by random allocation, then the trial is classified as an 'RCT'.

CT: a study in which treatment allocations are made using odd or even numbers, days of the week, or other such pseudo‐ or quasi‐random processes. These are not truly randomised and a study employing any of these techniques for assignment is classified as a CT. If a trial has not been described as randomised, but either is a quasi‐randomised study or may have been randomised or quasi‐randomised, then it is classified as a 'CT'. The classification is based solely on what the author has written, not on a reader's interpretation. Efforts will, however, be made to contact the authors for confirmation, if necessary.

CBA: a study design with contemporaneous data collection before and after the intervention, and an appropriate control site or activity. Prospective studies were considered eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

All trauma patients of any age.

Types of interventions

Trauma treatment at hospitals with an ATLS‐trained medical staff (or equivalent such as early management of severe trauma) compared with hospitals without an ATLS‐trained medical staff.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Death, to be analysed in the following categories: in‐hospital mortality, out‐of‐hospital mortality, 72 hour mortality and 30 day mortality

Secondary outcomes

Morbidity.

Search methods for identification of studies

In order to reduce publication and retrieval bias we did not restrict our search by language, date or publication status.

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Injuries Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the following:

Cochrane Injuries Group's Specialised Register (16th May 2014);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library) (issue 4 of 12 2014);

Ovid MEDLINE(R), Ovid MEDLINE(R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid OLDMEDLINE(R) (1946 to present) (16th May 2014);

Embase Classic + Embase (OvidSP) (1947 to 16th May 2014);

ISI Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED) (1970 to May 2014);

ISI Web of Science: Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science (CPCI‐S) (1990 to May 2014);

CINAHL Plus (EBSCO) (1937 to May 2014);

PubMed (16th May 2014).

The search strategies are also used for the review 'Advanced training in trauma life support for ambulance crews' (Jayaraman 2014) and are given in Appendix 1. Previous search methods are in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

Additionally, all references included in identified trials and background papers were checked to identify relevant published and unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the 2014 update, three authors (SJ, RW and PC) examined the electronic search results for reports of possibly relevant trials. Study quality was assessed using the recommendations outlined by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews Interventions (Higgins 2011) to determine the degree to which systematic bias may have been introduced, such as: bias through selection, performance, exclusion or detection; the method of allocation; the degree of follow‐up, and the soundness of the assessments. SJ, RW and PC categorised the studies as RCTs, CCTs and CBAs and applied these specific categories of quality assessment to the trial reports. Relevant reports were retrieved in full.

For the 2008 update, one author (SJ) examined the electronic search results for reports of possibly relevant trials. Study quality was assessed using the recommendations outlined by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews Interventions (Higgins 2011) to determine the degree to which systematic bias may have been introduced, such as: bias through selection, performance, exclusion or detection; the method of allocation; the degree of follow‐up, and the soundness of the assessments. SJ categorised the studies as RCTs, CCTs and CBAs and applied these specific categories of quality assessment to the trial reports. Relevant reports were retrieved in full.

For versions of the review through 2006, two authors (DS and SH) examined the electronic search results for reports of possibly relevant trials and these reports were retrieved in full. Both authors (SH and DS) applied the selection criteria independently to the trial reports.

Data extraction and management

The methodology outlined in the protocol for this review (Habibula 2002) indicates that three authors (SJ, RW and PC) would independently extract information on the following: type of study design (see above), stratification for effect modifiers, method of allocation concealment, number of randomised patients, type of participants and interventions, loss to and length of follow up. The outcome data sought were numbers of deaths and morbidity. The review authors would not be blinded to the authors of the trial reports or the journals in which they were published when undertaking the review. Results would be compared, and any differences resolved by discussion. Where there was insufficient information in the published report, authors would be contacted for clarification. As no studies for inclusion were found, these steps were not undertaken, but will be reserved for updates of the review should studies become available.

Data synthesis

In the future if studies are included in the review, risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals will be calculated for the comparisons outcomes of treatment provided in hospitals with ATLS‐trained staff versus hospitals without such training. We will follow the methods described in the latest version of the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011), and will use Review Manager (RevMan) software.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

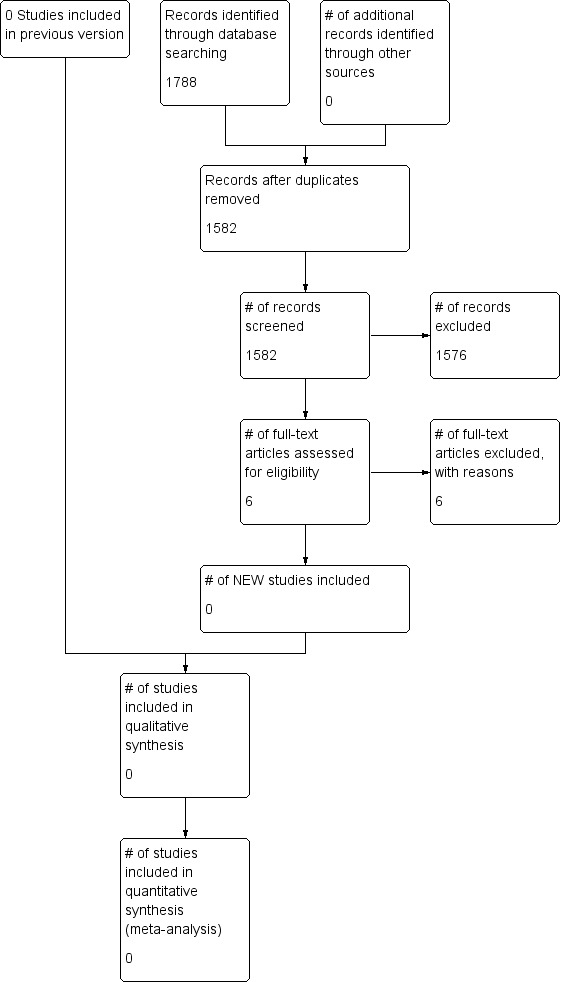

The updated search covered new citations published between 2009 and 2014. The details of search results are noted in Figure 1. Six studies were considered closely because they studied or seemed to study the population in question, however, none met our inclusion criteria for this review.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

No studies met the inclusion criteria.

Excluded studies

Previously, four studies were excluded because even though they showed improvements in processes of care, they did not report on patient outcomes such as death and morbidity because they failed to fulfill the pre‐set criteria of this review (Aboutanos 2007, Ali 1996, Ali 1998, Ali 2000).

Six more studies were considered but excluded for this review because they did not meet study criteria as noted below (Drimousis 2011, Hashmi 2013, Hedges 2002, Messick 1992, Wang 2010, Williams 1997).

Drimousis 2011 compared the mortality rates of two groups of physicians (ATLS certified or uncertified) in the same trauma setting over the same time period. However, no data were available on mortality rates of either group before the intervention (i.e. the ATLS training). The study therefore did not meet our inclusion criteria.

Hashmi 2013 conducted a before and after study after creating a specialized trauma team with members trained using advanced trauma life support, and establishing a western style trauma program including a registry and quality assurance program. They retrospectively entered patients to allow for a preimplementation and postimplementation study however this was not a controlled before‐after, therefore did not meet inclusion criteria for this review.

Hedges 2002 Retrospective, observational analysis correlating process‐of‐care variables with risk‐adjusted survival to determine if conduct of specific ATLS interventions were associated with improved survival for high‐risk patients. However because this was a retrospective study, it did not meet inclusion criteria for this review.

Messick 1992 evaluated prehospital ALS training and impact on trauma patient survival but this was a retrospective study without any controlled comparative populations, therefore did not meet inclusion criteria.

Wang 2010 compared mortality in severely injured trauma patients over two years before and two years after implementation of ATLS training for medical staff at one institution. However, this study was not a controlled before‐after study and therefore did not meet inclusion criteria.

Williams 1997 evaluated ATLS training in a simulated major incident situation. While they found that medical staff who had ATLS training reached more treatment objectives compared to those without ATLS training, this study did not meet inclusion criteria because it was not a controlled study involving patients.

Risk of bias in included studies

Since no studies met the inclusion criteria, consideration of risk of bias was not possible.

Effects of interventions

Since no studies met the inclusion criteria, the effects of interventions could not be considered.

Discussion

We did not find any study that met the inclusion criteria, despite conducting a very thorough literature search in which a total of 3109 citations, were screened to identify eligible trials. We believe it is unlikely that relevant trials have been overlooked since a search for new studies has been conducted every few years since 2004.

At present, the evidence base for the impact of an ATLS training programme (or equivalent) on trauma outcomes is poor. This is not entirely unexpected, as ATLS training is an educational approach rather than a process approach per se, and the evaluation of initiatives that are entirely hospital or system‐based is complex and difficult. In addition, as ATLS training is applied to an individual, and individuals change their places of practice, it is difficult to quantify which patients have been treated by ATLS‐trained health professionals. However, there is some evidence that such educational interventions addressing emergencies and injury can increase knowledge of early and effective intervention (Aboutanos 2007, Ali 1996, Ali 1998, Ali 2000, Williams 1997).

In some hospitals, ATLS training forms part of a process approach to trauma care, of which the establishment of trauma teams is an example. In some cities, this has been taken further with the introduction of trauma systems that 'stream' patients to particular receiving hospitals. Needless to say, trying to separate the influence of education, process approaches, experience related to higher patient volumes, and systems issues, is methodologically challenging and, to date, has not been completed. There is no evidence to conclude that educational interventions such as ATLS or similar training are not valuable. ATLS principles can be easily, and cost effectively, incorporated into undergraduate or post‐graduate training programmes and teach an approach that is transferable to other critically ill patients. The more difficult questions revolve around the formal interaction between ATLS training and systems of care within hospitals and health care systems. This review highlights the lack of rigorous evidence to show that ATLS training results in improved outcomes from injury and highlights the complexity of conducting such research, in view of the systems‐related issues.

We are aware that advocates for the expansion of ATLS programmes will point out that the aim of this training has always been to improve the knowledge and skills of individual doctors. In our inclusion criteria for this review we did not specify studies that attempted to assess whether such improvements were achieved, believing that reductions in mortality and morbidity are the ultimate goals of such interventions. It is also true that the number of doctors who have undergone ATLS training will vary considerably between hospitals, as training may often be done on an individual rather than an institutional basis.

It is possible that there may be studies of ATLS programmes which have examined outcomes falling outside our inclusion criteria. As with all systematic reviews, it is worth remembering that no evidence of effect does not equal evidence of no effect. Nevertheless, we believe that our review highlights the lack of evidence on which to base current practice and policy in many countries.

This review emphasises the need to conduct well designed intervention studies to establish the effectiveness and impact of trauma services, in order to ensure that policies, particularly in LMICs, are based on firm supporting evidence. A number of factors need to be taken into account when planning evaluative and comparative research of the effectiveness of hospitals, or health systems with trauma systems that incorporate ATLS training to reduce mortality and morbidity following trauma. These include the impact of pre‐hospital interventions, the impact of scene time (i.e. time ambulance staff spend at scene of injury), the mechanism of trauma (blunt versus penetrating), injury severity, injury pattern (presence and severity of head injury), and the mode of pre‐hospital transport. A conventional RCT is unlikely to be able to address such questions, given the problems of comparing different levels of training and different trauma systems, unless it is large, with cluster randomisation and a factorial design. A controlled, sequential before‐and‐after design (similar to the Ontario Prehospital Advanced Life Support Study (Stiell 1999)), conducted in a health system that currently does not have an organised trauma response is likely to be able to answer this question and the related question of the value of advanced life support interventions by pre‐hospital health care providers.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There are no controlled trials of the effect of ATLS training (or similar) on outcomes of injury victims. There is some evidence that educational initiatives improve knowledge of immediate emergency response and treatment of injured patients (Kelly 1994). Future research should concentrate on the evaluation of trauma systems with ATLS training, both within hospitals and at the health system level.

Implications for research.

In view of the wide acceptance in high income countries that trauma systems incorporating ATLS programmes are beneficial to injury victims, and its widespread implementation, it may be difficult to conduct evaluative research in these settings. Future research should concentrate on the evaluation of trauma systems, both within hospitals and at the health system level. A controlled, sequential before‐and‐after design (similar to the Ontario Prehospital Advanced Life Support Study) conducted in a health system that does not currently have an organised trauma response is likely to be able to answer this question. This may be preferable to an RCT, given the problems of comparing different levels of training and differences in trauma systems, unless the trial is large, with cluster randomisation and a factorial design.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 August 2014 | New search has been performed | The search has been updated to 16 May 2014. No new studies were identified. The results and conclusions have not changed. |

| 7 August 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Paul Chinnock and Roger Wong have been added as authors. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2003 Review first published: Issue 3, 2004

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 20 January 2009 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New studies sought but none found. Conclusions remain the same. The authors of the review have changed. |

| 9 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 12 July 2006 | New search has been performed | New studies sought but none found. Conclusions remain the same. Search updated to 1 July 2006. |

Acknowledgements

Shakiba Habibula and Anne‐Maree Kelly were authors of this review for versions through 2006.

We are grateful to the staff of the Cochrane Injuries Group editorial base for their technical support.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

Zetoc was searched as part of the original review, however, it did not yield any eligible trials and therefore was not searched for the 2014 udpate.

Cochrane Injuries Group's Specialised Register

((emerg* or trauma) and (prehospital or pre‐hospital or preclinical or pre‐clinical)) or "life support" or "Primary survey" or "golden hour" or "first aid" or "early management" or EMST or "advanced trauma life support" or ATLS or "advanced life support" or ALS or basic life support or BLS

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library)

#1MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Medical Services] explode all trees #2MeSH descriptor: [Critical Care] explode all trees #3MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Treatment] explode all trees #4MeSH descriptor: [Resuscitation] explode all trees #5MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Medicine] explode all trees #6MeSH descriptor: [First Aid] explode all trees #7MeSH descriptor: [Traumatology] explode all trees #8#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 #9MeSH descriptor: [Advanced Cardiac Life Support] explode all trees #10((Advanced trauma life support or ATLS) not (ATLS near/3 syndrome*)):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #11(Advanced life support or ALS):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #12(basic life support or BLS):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #13((emergency or trauma or critical) near/3 (care or treat*)):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #14((trauma near/3 system*) or (life near/3 support*) or (primary near/3 survey*) or (golden adj3 hour) or (first near/3 aid*)):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #15EMST:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #16(early management near/3 trauma):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #17((prehospital or pre‐hospital or preclinical or pre‐clinical) near/3 (care or support or treat*)):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #18#9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 #19#8 and #18 #20MeSH descriptor: [Health Personnel] explode all trees #21MeSH descriptor: [Allied Health Personnel] explode all trees #22MeSH descriptor: [Medical Staff] this term only #23paramedic*:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #24MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Medical Technicians] explode all trees #25((emergency or critical or trauma or triage or ambulanc*) near/3 (doctor* or crew* or staff or team*)):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #26#20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25

MEDLINE (OvidSP)

1. exp Emergency Medical Services/ 2. exp Critical Care/ 3. exp Emergency Treatment/ 4. exp Resuscitation/ 5. exp Emergency Medicine/ 6. exp First Aid/ 7. exp Traumatology/ 8. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 9. exp Advanced cardiac life support/ 10. ((Advanced trauma life support or ATLS) not (ATLS adj3 syndrome*)).ti,ab. 11. (Advanced life support or ALS).ti,ab. 12. (basic life support or BLS).ab,ti. 13. ((emergency or trauma or critical) adj3 (care or treat*)).ab,ti. 14. ((trauma adj3 system*) or (life adj3 support*) or (primary adj3 survey*) or (golden adj3 hour) or (first adj3 aid*)).ab,ti. 15. EMST.ab,ti. 16. (early management adj3 trauma).ab,ti. 17. ((prehospital or pre‐hospital or preclinical or pre‐clinical) adj3 (care or support or treat*)).ab,ti. 18. 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 19. 8 and 18 20. exp health personnel/ 21. exp allied health personnel/ 22. Medical staff/ 23. paramedic*.ab,ti. 24. exp Emergency Medical Technicians/ 25. ((emergency or critical or trauma or triage or ambulanc*) adj3 (doctor* or crew* or staff or team*)).ab,ti. 26. 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 27. 19 and 26 28. clinical trials as topic.sh. 29. randomi?ed.ti,ab. 30. randomized controlled trial.pt. 31. controlled clinical trial.pt. 32. (controlled adj3 ("before and after" or trial* or study or studies or evaluat*)).ab,ti. 33. randomized.ab. 34. placebo.ti,ab. 35. ((before adj3 after) or (interrupted adj3 time)).ab,ti. 36. randomly.ab. 37. trial.ti. 38. (groups or cohorts).ti,ab. 39. (observed or observation*).mp. 40. ((compar* or intervention or evaluat*) adj3 (trial* or stud*)).ab,ti. 41. (random* adj3 allocat*).ab,ti. 42. exp prospective studies/ 43. exp follow‐up studies/ 44. exp comparative study/ 45. exp cohort studies/ 46. exp evaluation studies/ 47. 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 48. 27 and 47

EMBASE (OvidSP) 1. exp Emergency/ 2. exp emergency health service/ 3. exp Emergency Treatment/ 4. exp intensive care/ 5. exp resuscitation/ 6. exp emergency medicine/ 7. exp traumatology/ 8. exp neurotraumatology/ 9. exp First aid/ 10. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 11. ((Advanced trauma life support or ATLS) not (ATLS adj3 syndrome*)).ti,ab. 12. (Advanced life support or ALS).ti,ab. 13. (basic life support or BLS).ab,ti. 14. ((emergency or trauma or critical) adj3 (care or treat*)).ab,ti. 15. ((trauma adj3 system*) or (life adj3 support*) or (primary adj3 survey*) or (golden adj3 hour) or (first adj3 aid*)).ab,ti. 16. EMST.ab,ti. 17. (early management adj3 trauma).ab,ti. 18. ((prehospital or pre‐hospital or preclinical or pre‐clinical) adj3 (care or support or treat*)).ab,ti. 19. 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 20. exp medical staff/ 21. exp paramedical personnel/ 22. paramedic*.ab,ti. 23. ((emergency or critical or trauma or triage or ambulanc*) adj3 (doctor* or crew* or staff or team*)).ab,ti. 24. 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 25. 10 and 19 and 24 26. exp Randomized Controlled Trial/ 27. exp controlled clinical trial/ 28. randomi?ed.ab. 29. placebo.ab. 30. exp Clinical Trial/ 31. randomly.ab. 32. (random* adj3 allocat*).ab,ti. 33. trial.ti. 34. (controlled adj3 ("before and after" or trial* or study or studies or evaluat*)).ab,ti. 35. ((before adj3 after) or (interrupted adj3 time)).ab,ti. 36. (groups or cohorts).ab,ti. 37. (observ* adj3 (trial* or stud*)).ab,ti. 38. ((compar* or intervention* or evaluat*) adj3 (trial* or stud*)).ab,ti. 39. exp prospective study/ 40. exp follow up/ 41. exp comparative study/ 42. exp experimental study/ 43. observational study/ 44. exp quasi experimental study/ 45. exp cohort analysis/ 46. exp evaluation research/ 47. exp time series analysis/ 48. or/26‐47 49. 25 and 48 50. limit 49 to exclude medline journals

CINAHL Plus (EBSCO)

S39 S27 AND S38 S38 S28 OR S29 OR S30 OR S31 OR S32 OR S33 OR S34 OR S35 OR S36 OR S37 S37 (MH "Quantitative Studies") S36 TX random* N3 allocat* S35 (MH "Random Assignment") S34 TX placebo* S33 (MH "Placebos") S32 TX randomi?ed N3 control* N3 trial* S31 TI ( (singl* N3 blind*) or (doubl* N3 blind*) or (trebl* N3 blind*) or (tripl* N3 blind*) ) or TI ( (singl* N3 mask*) or (doubl* N3 mask*) or (trebl* N3 mask*) or (tripl* N3 mask*) ) or AB ( (singl* N3 blind*) or (doubl* N3 blind*) or (trebl* N3 blind*) ) or AB ( (singl* N3 mask*) or (doubl* N3 mask*) or (trebl* N3 mask*) or (tripl* N3 mask*) ) S30 TX clinical N3 trial* S29 PT clinical trial* S28 (MH "Clinical Trials+") S27 S19 AND S26 S26 S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23 OR S24 OR S25 S25 ((emergency or critical or trauma or triage or ambulanc*) N3 (doctor* or crew* or staff or team*)) S24 (MH "Emergency Medical Technicians") S23 paramedic* S22 (MH "Medical Staff") S21 (MH "Allied Health Personnel+") S20 (MH "Health Personnel+") S19 S8 AND S18 S18 S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 S17 (Advanced life support or ALS) S16 ((prehospital or pre‐hospital or preclinical or pre‐clinical) N3 (care or support or treat*)) S15 (early management N3 trauma) S14 EMST S13 ((trauma N3 system*) or (life N3 support*) or (primary N3 survey*) or (golden N3 hour) or (first N3 aid*)) S12 ((emergency or trauma or critical) N3 (care or treat*)) S11 (basic life support or BLS) S10 ((Advanced trauma life support or ATLS) not (ATLS N3 syndrome*)) S9 (MH "Advanced Cardiac Life Support+") S8 S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 S7 (MH "Traumatology") S6 (MH "First Aid") S5 (MH "Emergency Medicine") S4 (MH "Resuscitation+") S3 (MH "Emergency Treatment (Non‐Cinahl)+") S2 (MH "Critical Care+") S1 (MH "Emergency Medical Services+")

ISI Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED); Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐ Science (CPCI‐S)

#20 #19 AND #13 #19 #18 AND #17 #18 Topic=(human*) #17 #16 OR #15 OR #14 #16 TS=(((singl* OR doubl* OR trebl* OR tripl*) SAME (blind* OR mask*))) #15 TS=((controlled clinical trial OR controlled trial OR clinical trial OR placebo)) #14 TS=((randomised OR randomized OR randomly OR random order OR random sequence OR random allocation OR randomly allocated OR at random OR randomized controlled trial)) #13 #12 AND #9 #12 #11 OR #10 #11 TS=(((emergency or critical or trauma or triage or ambulanc*) near/3 (doctor* or crew* or staff or team*))) #10 TS=(paramedic*) #9 #8 OR #7 OR #6 OR #5 OR #4 OR #3 OR #2 OR #1 #8 TS=(((prehospital or pre‐hospital or preclinical or pre‐clinical) near/3 (care or support or treat*))) #7 TS=(("early management" near/3 trauma)) #6 TS=(EMST) #5 TS=(((trauma near/3 system*) or (life near/3 support*) or (primary near/3 survey*) or (golden near/3 hour) or (first near/3 aid*))) #4 TS=(((emergency or trauma or critical) near/3 (care or treat*))) #3 TS=((basic life support or BLS)) #2 TS=((Advanced life support or ALS)) #1 TS=((("Advanced trauma life support" or ATLS) not (ATLS near/3 syndrome*)))

PubMed [www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez/] ((((((((((controlled evaluat*[Title/Abstract]) OR controlled trial*[Title/Abstract]) OR controlled study[Title/Abstract]) OR controlled studies[Title/Abstract])) OR (((("controlled before and after"[Title/Abstract])) OR "interrupted time series"[Title/Abstract]) OR cohort*[Title/Abstract])) OR (((("Cohort Studies"[Mesh]) OR "Prospective Studies"[Mesh]) OR "Follow‐Up Studies"[Mesh]) OR "Evaluation Studies"[Publication Type])) OR ((((((("Comparative Study"[Publication Type]) OR "Randomized Controlled Trial"[Publication Type]) OR "Controlled Clinical Trial"[Publication Type])) OR (((((((randomized[Title/Abstract]) OR randomised[Title/Abstract]) OR placebo[Title/Abstract]) OR randomly[Title/Abstract]) OR trial[Title/Abstract]) OR groups[Title/Abstract]) OR group[Title/Abstract])))))) AND (((((((emergency[Title/Abstract] OR critical[Title/Abstract] OR trauma[Title/Abstract] OR triage[Title/Abstract] OR ambulanc*[Title/Abstract]) AND (doctor*[Title/Abstract] OR crew*[Title/Abstract] OR staff[Title/Abstract] OR team*[Title/Abstract]))) OR ((paramedic*[Title/Abstract]) OR para‐medic*[Title/Abstract])) OR (((("Health Personnel"[Mesh]) OR "Allied Health Personnel"[Mesh]) OR "Medical Staff"[Mesh]) OR "Emergency Medical Technicians"[Mesh]))) AND (((((((((((("Advanced Trauma Life Support Care"[Mesh]) OR (((((care[Title/Abstract]) OR support[Title/Abstract]) OR treatment*[Title/Abstract])) AND ((((prehospital[Title/Abstract]) OR pre‐hospital[Title/Abstract]) OR preclinical[Title/Abstract]) OR pre‐clinical[Title/Abstract]))) OR ((((care[Title/Abstract]) OR treat*[Title/Abstract])) AND (((emergency[Title/Abstract]) OR trauma[Title/Abstract]) OR critical[Title/Abstract]))) OR ((golden[Title/Abstract]) AND hour[Title/Abstract])) OR ((primary[Title/Abstract]) AND survey*[Title/Abstract])) OR ((life[Title/Abstract]) AND support*[Title/Abstract])) OR ((trauma[Title/Abstract]) AND system[Title/Abstract])) OR emst[Title/Abstract]) OR ((early management[Title/Abstract]) AND trauma[Title/Abstract])) OR ((((((("advanced trauma life support"[Title/Abstract]) OR atls[Title/Abstract]) OR als[Title/Abstract]) OR bls[Title/Abstract]) OR trauma system[Title/Abstract]) OR basic life support[Title/Abstract]) OR advanced life support[Title/Abstract]))) AND (((((((((((("Emergency Medical Services"[Mesh:noexp]) OR "Critical Care"[Mesh:noexp]) OR "Emergency Treatment"[Mesh:noexp]) OR "Resuscitation"[Mesh]) OR "Emergency Medicine"[Mesh]) OR "First Aid"[Mesh]) OR "Traumatology"[Mesh]) OR "Advanced Cardiac Life Support"[Mesh])) OR ((first[Title/Abstract]) AND aid*[Title/Abstract])) OR (((emergency[Title/Abstract]) OR trauma[Title/Abstract]) OR critical[Title/Abstract])))))) NOT medline[sb]

Appendix 2. Previous search methods to 2008

This update included a more specific search strategy using additional criteria on research methods and expanded the search to include all years until September 2008. For the 2006 update please see previous version of review.

PUBMED (searched 2008)

#1 "Emergency Medical Services"[Mesh] OR "Critical Care"[Mesh]) OR "Emergency Treatment"[Mesh]) OR "Resuscitation"[Mesh]) OR "Emergency Medicine"[Mesh]) OR "Emergency Nursing"[Mesh]) OR "Life Support Care"[Mesh]) ) OR "Traumatology"[Mesh]) OR "Clinical Competence"[Mesh]) OR "First Aid"[Mesh] #2 (Advanced trauma life support or ATLS) NOT (ATLS AND syndrome*) Field: Title/Abstract #3 Advanced life support or ALS Field: Title/Abstract #4 Basic life support or BLS Field: Title/Abstract #5 (emergency or trauma or critical) AND (care or treat or treatment*) Field: Title/Abstract #6 (trauma AND system*) or (life AND support*) or (primary AND survey*) or (golden AND hour) or (first AND aid*) Field: Title/Abstract #7 (early management AND trauma) OR (EMST) Field: Title/Abstract #8 (prehospital or pre‐hospital or preclinical or pre‐clinical) AND (care or support or treat or treatment*) Field: Title/Abstract #9 #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 #10 #1 AND #9 #11 "Health Personnel"[Mesh] OR "Allied Health Personnel"[Mesh] OR "Nursing Staff"[Mesh] OR "Emergency Medical Technicians"[Mesh] #12 PARAMEDIC* Field: Title/Abstract #13 (emergency or critical or trauma or triage or ambulanc*) and (doctor* or nurse or nurses or nursing or crew or staff or team*) Field: Title/Abstract #14 #11 OR #12 OR #13 #15 #10 AND #14 #16 (randomised OR randomized OR randomly OR random order OR random sequence OR random allocation OR randomly allocated OR at random OR randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized controlled trials [mh]) NOT ((models, animal[mh] OR Animals[mh] OR Animal Experimentation[mh] OR Disease Models, Animal[mh] OR Animals, Laboratory[mh]) NOT (Humans[mh])) #17 #15 AND #16

ZETOC (searched 2008)

Emergency life support train*: 42 records Trauma life support train*: 31 records Emergency life support educat*:17 records Trauma life support educat*: 9 records

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Aboutanos 2007 | Looked specifically at the acquisition and retention of ATLS knowledge and skills, the costs of running courses, and the subjective experiences of the trainees. Did not report on patient outcomes such as death and morbidity, and thus did not meet the inclusion criteria. |

| Ali 1996 | Evaluated teaching effectiveness of ATLS courses for physicians using Objective Structured Clinical Examination. Did not report on patient outcomes such as death and morbidity, and thus did not meet the inclusion criteria. |

| Ali 1998 | Looked at the acquisition of ATLS knowledge and skills by medical students. Did not report on patient outcomes such as death and morbidity, and thus did not meet the inclusion criteria. |

| Ali 2000 | Evaluated teaching effectiveness of ATLS courses for surgery residents using a trauma mannequin. Did not report on patient outcomes such as death and morbidity, and thus did not meet the inclusion criteria. |

| Drimousis 2011 | A prospective study that, 'compares ATLS® and non‐ATLS® certified physicians’ performance in the same trauma setting and in the same time period'. However, there is no data on the performance of the two groups of physicians before the ATLS training/certification took place. Does not meet the review's requirement for a controlled before‐after study. |

| Hashmi 2013 | A before and after study but not a controlled before‐after, therefore did not meet inclusion criteria. |

| Hedges 2002 | Retrospective, observational analysis therefore did not meet inclusion criteria. |

| Messick 1992 | Evaluated prehospital ALS training and impact on trauma patient survival but retrospective study, therefore did not meet inclusion criteria. |

| Wang 2010 | A before and after study but not a controlled before‐after, therefore did not meet inclusion criteria. |

| Williams 1997 | Studied management of simulated trauma cases by ATLS and non‐ATLS staff. Did not report on patient outcomes such as death and morbidity, and thus did not meet the inclusion criteria. |

Contributions of authors

DS developed the protocol. For versions of the review through 2006, SH and DS performed the literature search and screened articles, extracted data and assessed study quality. SH contacted authors and entered data into Review Manager (RevMan) software. DS, AMK and SH wrote the review. For the 2008 update, SJ performed the literature search, screened articles, extracted data and assessed study quality. SH contacted trial report authors, and entered data into Review Manager (RevMan) software and updated the text of the review. DS approved the final version of the manuscript. For the 2014 update, SJ, PC and RW screened the search results, extracted data, assessed study quality, and updated the text of the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, Department of Surgery, USA.

Declarations of interest

SJ: None known.

DS: None known.

PC: None known.

RW: None known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies excluded from this review

Aboutanos 2007 {published data only}

- Aboutanos M, Rodas B, Aboutanos E, Mora S, Wolfe F, Duane G, et al. Trauma Education and Care in the Jungle of Ecuador, Where There is no Advanced Trauma Life Support. The Journal of Trauma 2007;62(3):714‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ali 1996 {published data only}

- Ali J, Cohen R, Adam R, Gana T, Pierre J, Bedaysie I, et al. Teaching effectiveness of the advanced trauma life support program as demonstrated by an objective structured clinical examination for practicing physicians. World Journal of Surgery 1996;20(8):1121‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ali 1998 {published data only}

- Ali J, Cohen R, Gana J, Al‐Bedah T. Effect of the Advanced Trauma Life Support Program on Medical Students' Performance in Simulated Trauma Patient Management. The Journal of Trauma 1998;44(4):588‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ali 2000 {published data only}

- Ali J, Gana T, Howard M. Trauma Mannequin Assessment of Management Skills of Surgical Residents after Advanced Trauma Life Support Training. Journal of Surgical Research 2000;93(1):197‐200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Drimousis 2011 {published data only}

- Drimousis PG, Theodorou D, Toutouzas K, Stergiopoulos S, Delicha EM, Giannopoulos P, et al. Advanced Trauma Life Support certified physicians in a non trauma system setting: is it enough?. Resuscitation 2011;82(2):180‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hashmi 2013 {published data only}

- Hashmi ZG, Haider AH, Zafar SN, Kisat M, Moosa A, Siddiqui F, et al. Hospital‐based trauma quality improvement initiatives: first step toward improving trauma outcomes in the developing world. The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 2013;75(1):60‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hedges 2002 {published data only}

- Hedges JR, Adams AL, Gunnels MD. ATLS practices and survival at rural level III trauma hospital, 1995‐1999. Prehospital Emergency Care 2002;6(3):299‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Messick 1992 {published data only}

- Messick W, Rutledge R, Meyer A. The Association of Advanced Life Support Training and Decreased Per Capita Trauma Death Rates: An Analysis of 12,417 Trauma Deaths. Journal of trauma 1992;33(6):850‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wang 2010 {published data only}

- Wang P, Li NP, Gu YF, Lu XB, Cong JN, Yang X, Ling Y. Comparison of severe trauma care effect before and after advanced trauma life support training. Chinese Journal of Traumatology 2010;13(6):341‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Williams 1997 {published data only}

- Williams M, Lockey J, Culshaw S. Improved trauma management with advanced trauma life support (ATLS) training. Journal of Accident and Emergency Medicine 1997;14(2):81‐3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Ali 1994

- Ali J, Adam R, Stedman M, Howard M, Williams JI. Advanced Trauma Life Support Program increases emergency room application of trauma resuscitative procedures in a developing country. Journal of Trauma 1994;36(3):391‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Berger 1996

- Berger LR, Mohan D. Injury control: a global view. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Cales 1984

- Cales RH. Trauma mortality in Orange County: the effect of implementation of a regional trauma system. Annals of Emergency Medicine 1984;13(1):1‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Calicott 1980

- Calicott PE, Hughes I. Training in trauma advanced life support. Journal of the American Medical Association 1980;243(11):1156‐9. [Google Scholar]

Gwatkin 1997

- Gwatkin DR, Heuveline P. Improving the health of the world's poor. Communicable diseases among young people remain central. BMJ 1997;315(7107):497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Habibula 2002

- Shakiba S, Sethi D, Maree‐Kelly A. Advanced trauma life support training for hospital staff. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004173] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Jayaraman 2014

- Jayaraman S, Sethi D, Wong R. Advanced trauma life support training for ambulance crews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 8. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003109.pub4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kelly 1994

- Kelly AM, Ardagh MW. Does learning emergency medicine equip medical students for ward emergencies?. Medical Education 1994;28(6):524‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kirsch 1998

- Kirsch TD. Emergency medicine around the world. Annals of Emergency Medicine 1998;32(2):237‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lecky 2000

- Lecky F, Woodford M, Yates DW. Trends in trauma care in England and Wales 1989‐97. Lancet 2000;355(9217):1771‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lopez 2006

- Lopez A, Mathers D, Ezzati C, Jamison M, Murray D. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. The Lancet 2006;367(9524):1747‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mathers 2006

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Medicine 2006;3(11):e442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Murray 1997a

- Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997;349(9063):1269‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Murray 1997b

- Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990‐2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997;349(9064):1498‐1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Murray 1997c

- Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Mortality by cause for the eight regions of the world: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997;349(9061):1436‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reines 1988

- Reines HD, Bartlett RL, Chudy NE, Kiragu KR, McKnew MA. Is advanced life support appropriate for victims of motor vehicle accidents: the South Carolina highway trauma project. Journal of Trauma 1988;28(5):563‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.0. Copenhagen: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

Roberts 1996

- Roberts I, Cambell F, Hollis SS, Yates D. Reducing accident death rates in children and young adults: the contribution of hospital care. BMJ 1996;313(7067):1239‐41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sethi 2000

- Sethi D, Aljunid S, Sulong SB, Zwi A. Injury care in low and middle‐income countries: identifying potential for change. Injury Control and Safety Promotion 2000;7(3):153‐64. [Google Scholar]

Stiell 1999

- Stiell IG, Wells GA, Spaite DW, Nichol G, O'Brian B, Munkley DP. The Ontario Prehospital Advanced Life Support (OPALS) study Part II: Rationale and methodology for trauma and respiratory distress patients. OPALS Study Group. Annals of Emergency Medicine 1999;34(2):256‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 2004

- WHO. World report on road traffic injury prevention. WHO 2004.