Commentary on ‘Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China’, by D. Wang et al., JAMA 2020; doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585

Disclaimer: This commentary was finalized on 24 March 2020, which should be considered in light of the rapidly developing understanding of COVID-19.

On 31 December 2019, China alerted the World Health Organization (WHO) to several cases of an uncommon pneumonia in Wuhan, the most populous city in Central China with >11 million people. The causal pathogen was unknown. In the initial stages, severe acute respiratory infection symptoms appeared, and some patients also quickly developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute respiratory failure, and other additional problems of a severe nature. On 7 January, a new coronavirus was recognized by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from the throat swab sample of a patient,1 and then officially named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by the WHO. Since then, the disease has quickly spread from Wuhan to other regions. Now, the WHO has declared the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a pandemic, with substantial occurrences in >100 countries around the world, with cases rapidly increasing at the time of publication of this Commentary.2

Understanding the detailed clinical characteristics of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 is of paramount importance to identify subjects at the highest risk of (i) being infected and (ii) presenting with a particularly severe clinical presentation which may lead to death. Recent reports from China, such as a study from Wang et al.,3 have demonstrated that old age as well as additional underlying health conditions significantly increases the risk of dying from infection. Importantly, cardiovascular disease, including hypertension, appears to be particularly linked to the severity of COVID-19.3–7 In a large-scale report from China’s CDC,7 patients who needed admission to an intensive care unit were more likely to have comorbidities, the majority of which were cardiovascular- or diabetes-associated. Even though the mortality rate remains highly variable depending on the region (currently 2.3% in China, and >9% in Italy or Spain), the large-scale analysis of 44 672 confirmed COVID-19 cases indicated an increased mortality risk for older patients (14.8% for patients ≥80 years of age), and for those with diabetes (7.3%), hypertension (6%), and cardiovascular disease (10.5%). Remarkably, the case fatality rate for underlying cardiovascular disease (10.5%) is larger than for patients with underlying chronic respiratory disease (6.3%).7 This is somewhat unexpected as compared with, for instance, the 2009 H1N1 influenza outbreak, where immunosuppressed patients were primary affected.8 As emerging worldwide evidence becomes accessible, studies from international cohorts will help to stratify the risk for more severe forms of COVID-19 for patients with pre-existing cardiovascular diseases.

The mechanisms of this association remain unclear. Unquestionably, the disparity between augmented metabolic demand and reduced cardiovascular reserve may represent one of the possible mechanisms.9

Viral infections are linked to increased metabolic demands by four- to eight-fold when compared with the normal physiological workload of the heart. This is comparable to significant exercise. This, in addition to the possible direct effects of pneumonia, can impair cardiac function. Other possible mechanisms may include high levels of expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a membrane-bound aminopeptidase used by the SARS-CoV-2 virus to invade host cells in cardiac tissues (separate from lung symptoms).10 In patients with existing cardiovascular conditions, symptoms of COVID-19 appear to be more severe, which might be related to augmented ACE2 expression in these individuals compared with healthy humans—although this remains speculative, as evidence of increased ACE2 in humans is not sufficient. Thus, further understanding of the injury triggered by COVID-19 to the heart and of the underlying pathways is of the utmost relevance, so that therapeutic measures delivered to these patients can be precise and effective, leading to decreased mortality.

If we consider the severe metabolic demand and cardiac dysfunction observed particularly in patients with co-existent hypertension, diabetes, and cardiac disease, the use of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor antagonists might be justified and beneficial.11 Experimental evidence, however, suggests that ACE2 used by SARS-CoV-2 to access host cells may be up-regulated by these medications, raising questions about the therapeutic use of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors if they promote increased ACE2 levels. Due to the crucial functional relevance of ACE2 to SARS-CoV-2, the possible effects of antihypertension therapeutics with angiotensin receptor blockers or ACE inhibitors in patients infected with COVID-19 have to be prudently deliberated.12

Reports suggest also that COVID-19 can cause acute cardiac complications. Acute myocardial injury appeared in 5 of the first 41 humans detected with this virus in Wuhan, who mostly expressed an increase level of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI; >28 pg/mL).4 In another comprehensive case report of 138 hospitalized COVID-19 patients, Wang et al. demonstrated that 16.7% of them developed arrhythmia and 7.2% developed acute cardiac injury.3 Unpublished first-hand data also demonstrated the development of fulminant myocarditis. In fact, in all influenza pandemics, cardiac events exceeded all other causes of death, including pneumonia.8 The mechanism of acute cardiac injury triggered by COVID-19 described here might be related to ACE2, as explained before. Other alternative mechanisms comprise a cytokine storm activated by an excessive reaction by type 1 and 2 T-helper cells,13 as well as hypoxaemia and respiratory dysfunction instigated by SARS-CoV-2, causing damage to myocardial cells.12 In line with this, inflammation markers, such as plasma high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), as well as levels of cytokines linked to cardiovascular risk, are also related to adverse outcomes and could be used as possible biomarkers of overall increased risk.14

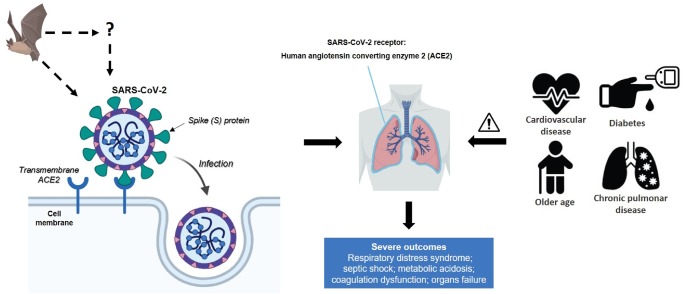

Figure 1.

Bats are the source of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV)-related viruses. SARS-CoV-2 may originate from bats or unidentified intermediary hosts and cross the species barrier into humans. Spike (S) glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 binds to the host cell receptors, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is a crucial step for virus entrance. SARS-CoV-2 mainly invades alveolar epithelial cells, resulting in respiratory symptoms. Host factors can also influence vulnerability to infection and disease evolution. Older patients with underlying diseases are vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 and tend to progress into severe complications. The severity in patients with cardiovascular diseases may be associated with increased secretion of ACE2 in these patients compared with healthy individuals. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

Questions also arise regarding chronic and long-term effects of COVID-19 on the cardiovascular system. A follow-up survey (12 years) of recovered patients who were previously infected with SARS-CoV (which has a similar structure to SARS-CoV-2) demonstrated that 44% had cardiovascular system abnormalities, 60% had glucose metabolism disorders, and 68% had hyperlipidaemia.15 No targeted therapies are available, and existing management comprises disease containment and mitigation on a populational level, including travel limitations, patient quarantine, and supportive medical care.

COVID-19 is a quickly evolving public health emergency, having spread rapidly since it was first recognized in Wuhan with a wide spectrum of severity. In early 2020, the WHO believed that it did not expect a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 to become available in less than 1.5 years. In the meanwhile, protocols for the supervision of COVID-19 patients with heart diseases and/or cardiovascular patients with COVID-19 should be established in detail.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding

Rui Adão is supported by Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology through project IMPAcT- PTDC/MED-FSL/31719/2017.

Authors

Biography: Rui is a Biologist with a PhD degree in Cardiovascular Sciences obtained in 2019 at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Porto (Portugal), where he currently works as a postdoctoral research scientist at the Cardiovascular Research and Development Center-UnIC. Rui has a strong expertise in animal models of pulmonary arterial hypertension (e.g. monocrotaline, hypoxia-Sugen5416) and in in vivo and in vitro evaluation of cardiac function. Rui has also maintained relevant collaborations with institutions of excellence in cardiovascular research and therapeutic innovation, including INSERM (France), Medical University of Graz (Austria), Christchurch School of Medicine (New Zealand), and Antwerp University (Belgium). As an early career researcher, he has won numerous prestigious scholarships and awards such as a Janssen Inovation Award (2018) and European Respiratory Society Short-Term Fellowship Grant (2017). His current research focuses on elucidating the role and therapeutic potential of novel small molecules (e.g. small peptides and microRNAs) in the setting of pulmonary arterial hypertension and associated heart failure. He is also a core member of the Scientists of Tomorrow Nucleus of the European Society of Cardiology.

Biography: Professor Tomasz J. Guzik is the current Editor-in-Chief of Cardiovascular Research. He is the Regius Professor of Physiology and Cardiovascular Pathobiology and an Honorary Consultant Physician in Cardiology at the University of Glasgow. He also serves as a Professor of Medicine at Jagiellonian University Collegium Medicum in Krakow, Poland. Notable recognitions include the honorary Bernard and Joan Marshall Prize in Research Excellence from the BSCR and the prestigious Corcoran Award Lecture at the American Heart Association. He is a recipient of European Research Council Grant. Professor Guzik research focusses on vascular biology, hypertension, and clinical immunology.

References

- 1. Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang CL, Chen HD, Chen J, Luo Y, Guo H, Jiang RD, Liu MQ, Chen Y, Shen XR, Wang X, Zheng XS, Zhao K, Chen QJ, Deng F, Liu LL, Yan B, Zhan FX, Wang YY, Xiao GF, Shi ZL.. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020;579:270–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. World Health Organization, 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19 (11 March 2020).

- 3. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z.. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020;323:1061–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B.. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020;395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, Xia J, Yu T, Zhang X, Zhang L.. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 2020;395:507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY,, Xiang J,, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J,, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS, China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu Z, McGoogan JM.. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020;doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yamauchi-Takihara K. What we learned from pandemic H1N1 influenza A. Cardiovasc Res 2011;89:483–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sack MN. The enigma of anti-inflammatory therapy for the management of heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 2020;116:6–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Y, Zhong N, Slutsky AS.. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med 2020;46:586–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Padro T, Manfrini O, Bugiardini R, Canty J, Cenko E, De Luca G, Duncker DJ, Eringa EC, Koller A, Tousoulis D, Trifunovic D, Vavlukis M, de Wit C, Badimon L.. ESC Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology and Microcirculation position paper on ‘coronary microvascular dysfunction in cardiovascular disease’. Cardiovasc Res 2020;116:741–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X.. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020;doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Turner AJ, Hiscox JA, Hooper NM.. ACE2: from vasopeptidase to SARS virus receptor. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2004;25:291–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pellicori P, Zhang J, Cuthbert J, Urbinati A, Shah P, Kazmi S, Clark AL, Cleland JGF.. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein in chronic heart failure: patient characteristics, phenotypes, and mode of death. Cardiovasc Res 2020;116:91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu Q, Zhou L, Sun X, Yan Z, Hu C, Wu J, Xu L, Li X, Liu H, Yin P, Li K, Zhao J, Li Y, Wang X, Li Y, Zhang Q, Xu G, Chen H.. Altered lipid metabolism in recovered SARS patients twelve years after infection. Sci Rep 2017;7:9110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]