Abstract

In a rapid response published online by the British Medical Journal, Sommerstein and Gräni1 pushed forward the hypothesis that angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (ACE-Is) could act as a potential risk factor for fatal Corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by up-regulating ACE2. This notion was quickly picked up by the lay press and sparked concerns among physicians and patients regarding the intake of inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2) infected individuals.1 In this article, we try to shed light on what is known and unknown regarding the RAAS and SARS-CoV2 interaction. We find translational evidence for diverse roles of the RAAS, which allows to formulate also the opposite hypothesis, i.e. that inhibition of the RAAS might be protective in COVID-19.

As of March 11, 124 910 patients worldwide have been tested positive for COVID-19 with a reported death toll amounting to 4589 patients, and the numbers continue to rise.2 First analyses of patient characteristics from China showed that diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases are highly prevalent among SARS-CoV2 infected patients, and may be associated with poor outcome.3 Specifically, their prevalence was roughly three- to four-fold increased among patients reaching the combined primary endpoint of admission to an intensive care unit, mechanical ventilation, or death compared to patients with less severe outcomes. In general, patients with these conditions are frequently treated with inhibitors of the RAAS, namely ACE-Is, angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers (ARBs), or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs).

As previously shown for SARS-CoV,4 SARS-CoV25 similarly utilizes ACE2 as receptor for viral cell entry. In the RAAS, ACE2 catalyses the conversion of angiotensin II to angiotensin 1–7, which acts as a vasodilator and exerts protective effects in the cardiovascular system. In animal experiments, increased expression and activity of ACE2 in various organs including the heart were found in connection with ACE-I and ARB administration.6 In addition, more recent data showing increased urinary secretion of ACE2 in hypertensive patients treated with the ARB olmesartan suggest that up-regulation of ACE2 may also occur in humans.7 These observations have been reiterated in the literature and on the web in recent days and the question arose whether RAAS inhibition may increase the risk of deleterious outcome of COVID-19 through up-regulation of ACE2 and increase of viral load.

Despite the possible up-regulation of ACE2 by RAAS inhibition and the theoretically associated risk of a higher susceptibility to infection, there is currently no data proving a causal relationship between ACE2 activity and SARS-CoV2 associated mortality. Furthermore, ACE2 expression may not necessarily correlate with the degree of infection. Although ACE2 is thought to be mandatory for SARS-CoV infection, absence of SARS-CoV was observed in some ACE2 expressing cell types, whereas infection was present in cells apparently lacking ACE2, suggesting that additional co-factors might be needed for efficient cellular infection.8 In addition, lethal outcome of COVID-19 is mostly driven by the severity of the underlying lung injury. Importantly, in a mouse model of SARS-CoV infection and pulmonary disease, a key pathophysiological role was shown for ACE, angiotensin II and angiotensin II receptor type 1.9 SARS-CoV or SARS-CoV spike protein led to down-regulation of ACE2 and more severe lung injury in mice that could be attenuated by administration of an ARB9,10 These findings suggest a protective role of ARB in SARS-CoV associated lung injury and give rise to the hypothesis that primary activation of the RAAS in cardiovascular patients, rather than its inhibition, renders them more prone to a deleterious outcome.11

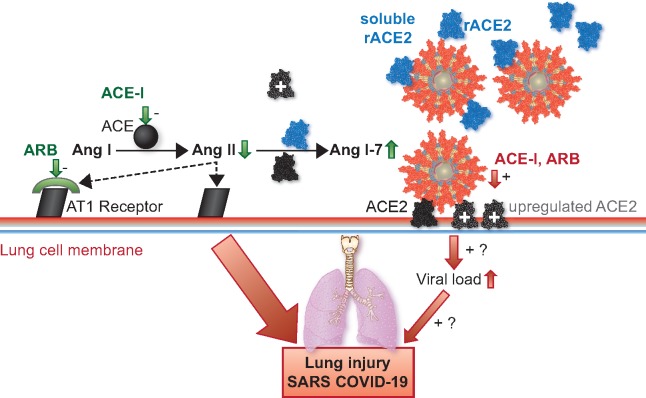

Take home figure.

Conceptual figure highlighting the central role of ACE2 in the potentially deleterious (red) and protective (green) effects of the RAAS and its inhibition in the development of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). ACE-Is and ARBs increase ACE2 expression and activity (grey) as shown by a few animal and human studies,6,7 but the mechanism has yet to be identified. Although there is currently no evidence, this could theoretically increase viral load and worsen outcome (red). In a reverse causality, ACE2 acts as a gatekeeper of the RAAS by degrading AngII to Ang1-7, hence diminishing its Ang II receptor 1-mediated deleterious effects. Therefore, ACE-I or ARB treatment could theoretically mitigate lung injury (green). Evidence for this mainly stems from animal studies.9,10 Providing soluble recombinant (r)ACE2 (blue) addresses both mechanisms by cell independent binding of SARS-CoV2 and degrading AngII to Ang 1-7. This concept is currently being tested in a pilot study in patients with COVID-19.13

It is important to note that Guan et al.3 do not report how many patients were taking ACE-Is or ARBs. Based on data from the China PEACE Million Persons Project, nearly half of Chinese adults between 35 and 75 years are suffering from hypertension, but fewer than one third receive treatment, and blood pressure control is achieved in less than 10%.12 Furthermore, there is thus far no data showing that hypertension or diabetes are independent predictors of fatal outcome. Therefore, based on currently available data and statistics, the assumption of a causal relationship between ACE-I or ARB intake and deleterious outcome in COVID-19 is not legitimate. In fact, in a case of reverse causality, patients taking ACE-Is or ARBs may be more susceptible for viral infection and have higher mortality because they are older, more frequently hypertensive, diabetic, and/or having renal disease.

Clearly, much more research is needed to clarify the multifaceted role of the RAAS in connection with SARS-CoV2 infection. Although there is data from animal studies suggesting potentially deleterious effects of the RAAS, prove-of-concept in humans is still lacking. Similarly, a few animal and human studies suggest up-regulation of ACE2 in response to RAAS inhibition through a yet to be identified mechanism, but whether this increases viral load in a critical way, and how viral load per se relates to disease severity remains unknown. Nevertheless, based on the work by Josef Penninger et al.,13 who proposed to therapeutically use the dual function of ACE2 as viral receptor and gatekeeper of RAAS activation, a pilot trial using soluble human recombinant ACE2 (APN01) in patients with COVID-19 has recently been initiated (Clinicaltrials.gov #NCT04287686). Such therapy could have the potential to lower both the viral load and the deleterious effects of angiotensin II activity.

In the meantime, we are well-advised to stick to what is known. There is abundant and solid evidence of the mortality-lowering effects of RAAS inhibitors in cardiovascular disease. ACE-Is, ARBs, and MRAs are the cornerstone of a prognostically beneficial heart failure therapy with the highest level of evidence with regard to mortality reduction.14 They all have in common the inhibition of the adverse cardiovascular effects arising from the interaction of angiotensin II with the angiotensin II receptor type 1. Discontinuation of heart failure therapy leads to deterioration of cardiac function and heart failure within days to weeks with a possible respective increase in mortality.15–17 Similarly, ACE-Is, ARBs, and MRAs are part of the standard therapy in hypertension18 and after myocardial infarction.19 Significant reduction of post-infarct mortality applies to all three substance classes, whereby early initiation of therapy (within days after infarction) is an important factor of success.20–23

In conclusion, based on currently available data and in view of the overwhelming evidence of mortality reduction in cardiovascular disease, ACE-I and ARB therapy should be maintained or initiated in patients with heart failure, hypertension, or myocardial infarction according to current guidelines as tolerated, irrespective of SARS-CoV2. Withdrawal of RAAS inhibition or preemptive switch to alternate drugs at this point seems not advisable, since it might even increase cardiovascular mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients.

Conflict of interest: O.P. reports personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Pfizer, grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants from Sanofi, personal fees from Vifor Pharma, personal fees from MSD, outside the submitted work. T.B. reports personal fees from Servier, Amgen, Takeda, Menarini, MSD, Sanofi, and Vifor, outside the submitted work. R.T. reports personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Roche Diagnostics, Siemens, Singulex, and Thermo Scientific BRAHMS, outside the submitted work. Q.Z. reports grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Astra Zeneca, grants from Abbott, personal fees from Novartis, other from Alnylam, and personal fees from Bayer, outside the submitted work. S.O. reports grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation for the SwissAF cohort study, outside the submitted work. All other authors declared no conflict of interest.

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of the European Heart Journal or of the European Society of Cardiology.

References

- 1. Sommerstein R, Gräni C.. Rapid response: re: preventing a covid-19 pandemic: ACE inhibitors as a potential risk factor for fatal Covid-19. BMJ 2020. https://www.bmj.com/content/368/bmj.m810/rr-2 (8 March 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dong E, Du H, Gardner L.. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (11 March 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, Sui J, Wong SK, Berne MA, Somasundaran M, Sullivan JL, Luzuriaga K, Greenough TC, Choe H, Farzan M.. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 2003;426:450–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH, Nitsche A, Müller MA, Drosten C, Pöhlmann S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, Averill DB, Brosnihan KB, Tallant EA, Diz DI, Gallagher PE.. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation 2005;111:2605–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Furuhashi M, Moniwa N, Mita T, Fuseya T, Ishimura S, Ohno K, Shibata S, Tanaka M, Watanabe Y, Akasaka H, Ohnishi H, Yoshida H, Takizawa H, Saitoh S, Ura N, Shimamoto K, Miura T.. Urinary angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in hypertensive patients may be increased by olmesartan, an angiotensin II receptor blocker. Am J Hypertens 2015;28:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gu J, Korteweg C.. Pathology and pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Am J Pathol 2007;170:1136–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Imai Y, Kuba K, Rao S, Huan Y, Guo F, Guan B, Yang P, Sarao R, Wada T, Leong-Poi H, Crackower MA, Fukamizu A, Hui CC, Hein L, Uhlig S, Slutsky AS, Jiang C, Penninger JM.. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature 2005;436:112–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuba K, Imai Y, Rao S, Gao H, Guo F, Guan B, Huan Y, Yang P, Zhang Y, Deng W, Bao L, Zhang B, Liu G, Wang Z, Chappell M, Liu Y, Zheng D, Leibbrandt A, Wada T, Slutsky AS, Liu D, Qin C, Jiang C, Penninger JM.. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med 2005;11:875–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gurwitz D. Angiotensin receptor blockers as tentative SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics. Drug Dev Res 2020. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lu J, Lu Y, Wang X, Li X, Linderman GC, Wu C, Cheng X, Mu L, Zhang H, Liu J, Su M, Zhao H, Spatz ES, Spertus JA, Masoudi FA, Krumholz HM, Jiang L.. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China: data from 1.7 million adults in a population-based screening study (China PEACE Million Persons Project). Lancet 2017;390:2549–2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Y, Zhong N, Slutsky AS.. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med 2020. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Falk V, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GMC, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer PESC Scientific Document Group. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2129–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pflugfelder PW, Baird MG, Tonkon MJ, DiBianco R, Pitt B.. Clinical consequences of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor withdrawal in chronic heart failure: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of quinapril. The Quinapril Heart Failure Trial Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;22:1557–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gilstrap LG, Fonarow GC, Desai AS, Liang L, Matsouaka R, DeVore AD, Smith EE, Heidenreich P, Hernandez AF, Yancy CW, Bhatt DL.. Initiation, continuation, or withdrawal of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers and outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e004675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Halliday BP, Wassall R, Lota AS, Khalique Z, Gregson J, Newsome S, Jackson R, Rahneva T, Wage R, Smith G, Venneri L, Tayal U, Auger D, Midwinter W, Whiffin N, Rajani R, Dungu JN, Pantazis A, Cook SA, Ware JS, Baksi AJ, Pennell DJ, Rosen SD, Cowie MR, Cleland JGF, Prasad SK.. Withdrawal of pharmacological treatment for heart failure in patients with recovered dilated cardiomyopathy (TRED-HF): an open-label, pilot, randomised trial. Lancet 2019;393:61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement DL, Coca A, de Simone G, Dominiczak A, Kahan T, Mahfoud F, Redon J, Ruilope L, Zanchetti A, Kerins M, Kjeldsen SE, Kreutz R, Laurent S, Lip GYH, McManus R, Narkiewicz K, Ruschitzka F, Schmieder RE, Shlyakhto E, Tsioufis C, Aboyans V, Desormais IESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2018;39:3021–3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimsky PESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018;39:119–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. ISIS-4: a randomised factorial trial assessing early oral captopril, oral mononitrate, and intravenous magnesium sulphate in 58,050 patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. ISIS-4 (Fourth International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. Lancet 1995;345:669–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Indications for ACE inhibitors in the early treatment of acute myocardial infarction: systematic overview of individual data from 100,000 patients in randomized trials. ACE Inhibitor Myocardial Infarction Collaborative Group. Circulation 1998;97:2202–2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, Neaton J, Martinez F, Roniker B, Bittman R, Hurley S, Kleiman J, Gatlin MEplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study Investigators. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1309–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Montalescot G, Pitt B, Lopez de Sa E, Hamm CW, Flather M, Verheugt F, Shi H, Turgonyi E, Orri M, Vincent J, Zannad F; REMINDER Investigators. Early eplerenone treatment in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction without heart failure: the Randomized Double-Blind Reminder Study. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2295–2302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]