Abstract

Background

The Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale–Irritable Bowel Syndrome (GSRS-IBS) is a 13-item measure of IBS symptom severity. The scale has been used in several studies, but its psychometric properties have been insufficiently investigated and population-based data are not available.

Objective

The objective of this article is to establish the factor structure and discriminant and convergent validity of the GSRS-IBS.

Methods

The study was based on a Swedish population sample (the Popcol study), of which 1158 randomly selected participants provided data on the GSRS-IBS. We used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and compared total and subscales scores in different groups, including IBS diagnostic status, treatment-seeking behavior, and predominant bowel habits. The GSRS-IBS scores were also correlated with quality of life indexes.

Results

The sample included 164 participants with a confirmed Rome III IBS diagnosis and 994 participants without the disease. The CFA confirmed the subscales with one exception, in which the incomplete bowel-emptying item belonged to the constipation subscale rather than the diarrhea subscale. The GSRS-IBS total score and subscales were associated with diagnostic status, treatment-seeking behavior, and quality of life dimensions. The relevant subscales scores also differed between the diarrhea- and constipation-predominant subtypes of IBS.

Conclusion

The GSRS-IBS total score and subscales have high discriminant and convergent validity. The CFA confirmed the overall validity of the subscales but suggest that a sense of incomplete emptying belongs to the constipation rather than the diarrhea symptom cluster. We conclude that the GSRS-IBS is an excellent measure of IBS symptom severity in the general population.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome, patient-reported outcomes, population study, psychometric evaluation, symptom severity

Key Summary

What is known

The Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale–Irritable Bowel Syndrome (GSRS-IBS) is a short measure of IBS symptom severity.

There are no data on the psychometric properties of the GSRS-IBS in the general population.

What is new here

GSRS-IBS scores are associated with IBS diagnostic status and treatment-seeking behavior in the general population.

GSRS-IBS scores are associated with quality of life indexes in the general population.

The GSRS-IBS is an excellent measure of IBS symptom severity in the general population.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder, characterized by abdominal pain and defecation disturbances1 and impaired quality of life.2 Although IBS is generally considered to be chronic, pharmacological and psychological interventions for IBS both have been demonstrated to lead to symptom relief.3

The primary outcome in treatment trials is often the effect on the overall symptom burden of IBS. One widely used measure of global symptom burden in IBS is the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale–IBS (GSRS-IBS).4 The GSRS-IBS includes 13 items that measure the severity of IBS symptoms in five clusters (pain, bloating, constipation, diarrhea, and early satiety) during the last seven days. In a validation study, Wiklund et al.4 found that factor analysis confirmed the five symptom clusters. Furthermore, the symptom clusters were correlated with different measures of quality of life and showed high test-retest reliability and internal consistency.4 Posserud and colleagues5 also showed that rectal sensitivity, in terms of discomfort and pain thresholds, was associated with GSRS-IBS total score and scores on the pain and bloating subscales. Furthermore, psychological treatment intervention studies have demonstrated that the GSRS-IBS can be used to quantify change in symptom severity (see, for example, Lindfors et al.,6 Ljótsson et al.7 and Hunt et al.8) and be used to measure treatment mechanisms,9,10 indicating that the GSRS-IBS is sensitive to change. A recent validation study of a mixed sample including IBS patients, other diagnostic groups, and healthy controls showed that GSRS-IBS separated IBS from other conditions and healthy controls and that GSRS-IBS score was associated with anxiety and depression severity.11

Although validation studies4,11 have indicated that the GSRS-IBS has adequate psychometric properties, data have been collected only from patients diagnosed with IBS or convenience samples. Thus, the psychometric properties of the scale in the general population are not known. Validation of the GSRS-IBS measure in a representative population sample that is also medically assessed would allow for estimating average GSRS-IBS scores in individuals with or without an IBS diagnosis. Furthermore, because only about half of individuals who fulfill criteria for a formal diagnosis of IBS consult a physician for GI symptoms, and symptom severity has been shown to predict treatment-seeking,12 the GSRS-IBS should differentiate between GI consultation treatment-seeking and non–treatment-seeking individuals in the general population. Finally, the diarrhea-predominant and constipation-predominant IBS subtypes should have different scores on the GSRS-IBS diarrhea and constipation subscales.

In addition, most studies that have used the GSRS-IBS to measure symptom severity before and after an intervention have reported the mean total score rather than scores on the individual subscales.6–8 However, the psychometric properties of the total score were not investigated in the original validation study by Wiklund and colleagues4 and are not known.

Thus, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the psychometric properties of the GSRS-IBS total score and subscales in a normal population. The following properties were investigated: factor structure; differentiation between individuals fulfilling and not fulfilling Rome III criteria for IBS,13 subdivided by treatment-seeking behavior; subscales scores in the IBS subtypes; and relationship with an established measure of quality of life. We hypothesized that the GSRS-IBS would be associated with IBS diagnostic status, treatment-seeking behavior, and IBS subtype. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the GSRS-IBS total score would correlate with quality of life indexes.

Methods

Participants

The present study is based on data collected from the Popcol population study.14 In the Popcol study, a random selection of 3556 adults (ages 18–70 years) living in two parishes in Stockholm, Sweden (total adult population 38,646 in the year 2000), were invited to participate in the study by mail and reminded by phone calls during 2002–2006. Individuals who completed and returned the Abdominal Symptom Questionnaire (N = 2293; data not reported in this paper) were further invited by phone to an evaluation by a gastroenterologist including completion of self-assessments, physical examination, and collection of medical history. A total of 1244 of the 1643 participants who were reached by phone agreed to the visit and completed the questionnaires reported in the present study. The questionnaires were completed on a personal digital assistant and, because of technical problems, some assessments were lost or not recorded. In total, GSRS-IBS data and IBS diagnostic status were available for 1158 participants. Further information about the Popcol study is available in Kjellström et al.14 All participants signed an informed consent, and the study was approved by the regional ethics committee in Stockholm on November 5, 2001 (No. 394/01). The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the regional ethics committee.

Procedure

During the visit, the gastroenterologists collected participants’ medical history, including previous medical consultations for abdominal complaints. Participants also completed a battery of self-assessments that included the questionnaires analyzed for the present study. The assessing gastroenterologists were blinded to the participants’ answers on the questionnaires.

Measurements

GSRS-IBS

The GSRS-IBS is a 13-item measure of GI symptom severity for the last seven days. The items measure severity of (1) abdominal pain, (2) pain relieved by a bowel action, (3) bloating, (4) passing gas, (5) constipation, (6) diarrhea, (7) loose stools, (8) hard stools, (9) urgent need for bowel movement, (10) incomplete bowel emptying, (11) fullness shortly after meal, (12) fullness long after eating, and (13) visible distension. The items are scored between 1 and 7, where 1 corresponds to “no discomfort at all” and 7 to “very severe discomfort” from the symptom. In the original validation study,4 the items were shown to belong to five symptom clusters: pain (items 1 and 2), bloating (items 3, 4 and 13), constipation (items 5 and 8), diarrhea (items 6, 7, 9 and 10), and early satiety (items 11 and 12). The items are scored between 1 and 7, where 1 corresponds to “no discomfort at all” and 7 to “very severe discomfort” from the symptom.

Short Form Health Survey–36 items (SF-36)

The SF-3615 is a widely used measure of health-related quality of life. It includes the following eight subscales: (1) physical functioning, (2) role limitations due to physical health, (3) role limitations due to emotional problems, (4) energy/fatigue, (5) emotional well-being, (6) social functioning, (7) pain, and (8) general health. The subscales have been found to be associated with severity both of physical and mental health problems.16

Rome III diagnosis and subclassification

The Rome II Modular Questionnaire17 includes questions about GI symptoms, including all key IBS symptoms. The scoring algorithm to diagnose participants with IBS and subclassify them into diarrhea predominant, constipation predominant, mixed subtyped, and unsubtyped was based on the Rome III criteria.13 This was possible because the time frame used in the Swedish translation of the Rome II Modular Questionnaire used in the present study was three months18 rather than the 12 months used for the Rome II criteria.

Analysis

All analyses were performed in R except the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which was performed in STATA.

Item analysis

The Cronbach alpha internal consistency estimate of reliability was calculated for the total GSRS-IBS score (i.e. including all 13 items). We also performed CFA to investigate the validity of the GSRS-IBS subscales. We evaluated two different sets of subscale scorings. In the first CFA, we followed the subscales scorings proposed by Wiklund et al.4 In the second CFA, we moved the Incomplete Emptying item from the diarrhea subscale to the constipation subscale. The second CFA analysis was performed because other studies of IBS symptom clusters have found that a sense of incomplete defecation is more related to constipation symptoms rather than diarrhea symptoms.19,20 CFA model fit targets were adopted from Schermelleh-Engel et al.,21 including the chi-square measure (ideally non–statistically significant), the ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom (ideally <5), comparative fit index (CFI, ideally >0.95) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA, ideally <0.05). Comparison of model fit between CFA models representing different construct theories was based on the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) because other fit statistics are not comparable across a non-nested model.

GSRS-IBS scores

Means and SD for the GSRS-IBS total and subscales scores were calculated for the whole sample, the sample divided into participants fulfilling and not fulfilling Rome III criteria for IBS, and the latter two groups further subdivided into participants reporting ever having sought health care for GI symptom (consulters) or not (nonconsulters).

Discriminatory validity

We tested whether GSRS-IBS total and subscale scores were significantly different between participants with and without an IBS diagnosis, and furthermore subdivided these groups into consulters and nonconsulters. We also compared GSRS-IBS total and subscale scores between the four IBS subtypes: diarrhea-predominant, constipation-predominant, mixed, and unsubtyped IBS.

Convergent validity

We explored the correlations between the GSRS-IBS total score and subscales and the SF-36 subscales.

Results

Demographics

Rome III diagnostic status of IBS was available for 1158 participants who all provided data on the GSRS-IBS for analysis, treatment-seeking status was available for 1150 participants, and 1157 participants provided data on the SF-36. Table 1 shows demographic data for the total sample and participants without (n = 994) and with (n = 164) a Rome III diagnosis. Participants with a Rome III diagnosis of IBS were significantly more often female, younger, and had sought more care for abdominal complaints than participants without an IBS diagnosis. There were no differences in education level or household size between participants with and without an IBS diagnosis.

Table 1.

Demographic data of included sample.

| Total Sample | Non-IBS | IBS | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1158 | 994 (85.8%) | 164 (14.2%) | |

| Female | 658 (56.8%) | 552 (55.5%) | 106 (64.6%) | .036 |

| Age mean (SD), y | 48.61 (13.34) | 49.45 (13.18) | 43.50 (13.20) | <.001 |

| GI consultation | 604 (52.2%) | 493 (49.6%) | 111 (67.7%) | <.001 |

| University education | 676 (58.4%) | 578 (58.1%) | 98 (59.8%) | .782 |

| Household size mean (SD) | 2.16 (1.08) | 2.15 (1.08) | 2.24 (1.09) | .317 |

GI: gastrointestinal; IBS: irritable bowel syndrome. Non-IBS and IBS: absence and presence of Rome III IBS diagnosis. GI consultation: any previous consultation for abdominal complaints.

Difference column shows p values of tests (chi-square or t-test) of difference between non-IBS and IBS.

Item analysis

Correlations between the items are displayed in Table 2. Cronbach alpha for the total GSRS-IBS score was .88, indicating acceptable internal consistency. The first CFA where subscales were scored as proposed by Wiklund et al.4 showed poor fit to the data (RMSEA = .122, CFI = .881, and TLI = .832) with a BIC value of 41,280.7. The second CFA where the Incomplete Emptying item was moved from the diarrhea to the constipation subscale showed considerably better and acceptable fit (RMSEA = .080, CFI = .957, TLI =.936) and a smaller BIC value of 36,978.1. In the following analyses, the five subscales were based on the better fitting model (lower BIC), i.e. the Incomplete Emptying item was included in the constipation subscale rather than the diarrhea subscale. The correlations between the subscales are displayed in Table 3. The lowest correlations were observed between the constipation and diarrhea subscales (r = .18) and between the early satiety subscale and the other subscales (r = .33–.44).

Table 2.

Intercorrelations with associated p values between Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale–Irritable Bowel Syndrome items.

| Item | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Abdominal pain | 0.72 <.001 | 0.58 <.001 | 0.40 <.001 | 0.39 <.001 | 0.44 <.001 | 0.46 <.001 | 0.35 <.001 | 0.47 <.001 | 0.46 <.001 | 0.37 <.001 | 0.37 <.001 | 0.52 <.001 |

| 2. Pain relief | 0.55 <.001 | 0.40 <.001 | 0.45 <.001 | 0.44 <.001 | 0.46 <.001 | 0.38 <.001 | 0.48 <.001 | 0.51 <.001 | 0.35 <.001 | 0.32 <.001 | 0.49 <.001 | |

| 3. Bloating | 0.46 <.001 | 0.39 <.001 | 0.30 <.001 | 0.28 <.001 | 0.32 <.001 | 0.28 <.001 | 0.48 <.001 | 0.30 <.001 | 0.37 <.001 | 0.70 <.001 | ||

| 4. Passing gas | 0.28 <.001 | 0.33 <.001 | 0.33 <.001 | 0.25 <.001 | 0.39 <.001 | 0.32 <.001 | 0.20 <.001 | 0.25 <.001 | 0.39 <.001 | |||

| 5. Constipation | 0.06 .031 | 0.02 .594 | 0.85 <.001 | 0.16 <.001 | 0.66 <.001 | 0.25 <.001 | 0.28 <.001 | 0.38 <.001 | ||||

| 6. Diarrhea | 0.66 <.001 | 0.05 .089 | 0.56 <.001 | 0.29 <.001 | 0.30 <.001 | 0.23 <.001 | 0.28 <.001 | |||||

| 7. Loose stools | -0.01 .770 | 0.64 <.001 | 0.23 <.001 | 0.27 <.001 | 0.20 <.001 | 0.27 <.001 | ||||||

| 8. Hard stools | 0.14 <.001 | 0.58 <.001 | 0.19 <.001 | 0.27 <.001 | 0.29 <.001 | |||||||

| 9. Urgency | 0.30 <.001 | 0.30 <.001 | 0.22 <.001 | 0.32 <.001 | ||||||||

| 10. Incomplete emptying | 0.34 <.001 | 0.32 <.001 | 0.41 <.001 | |||||||||

| 11. Immediate fullness | 0.55 <.001 | 0.32 <.001 | ||||||||||

| 12. Long fullness | 0.36 <.001 | |||||||||||

| 13. Distension |

Table 3.

Correlations among Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale–Irritable Bowel Syndrome total score and subscales.

| Subscale | Diarrhea | Constipation | Bloating | Pain | Early Satiety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.61 |

| Diarrhea | 0.18 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 0.33 | |

| Constipation | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.35 | ||

| Bloating | 0.64 | 0.41 | |||

| Pain | 0.44 |

All correlations are p less than 0.001.

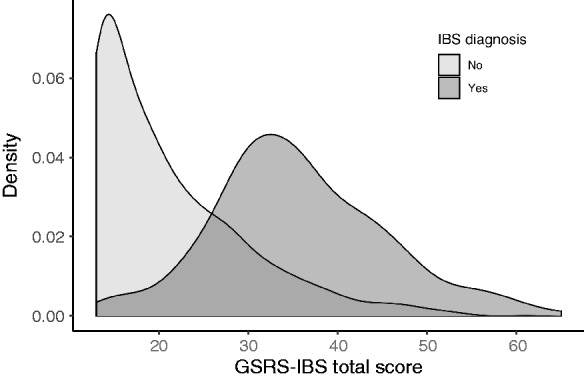

GSRS-IBS scores

The GSRS-IBS total and subscale scores are displayed in Table 4. The average GSRS-IBS total score in the whole sample was 23.21 (SD = 10.07), whereas the average scores for participants without and with an IBS diagnosis were 21.14 (SD = 8.52) and 35.72 (SD = 9.69), respectively. The average GSRS-IBS total score, regardless of diagnostic status, was higher among women (mean (M) = 24.90, SD = 10.64), than among men (M = 20.98, SD = 8.79, t[1148.1] = 6.85, p < 0.001). The distributions of total GSRS-IBS scores for participants with and without an IBS diagnosis are displayed in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Means and (SD) for Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale–Irritable Bowel Syndrome (GSRS-IBS) total score and subscales for total sample and sample subdivided according to Rome III diagnosis of IBS and consulting for gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms.

| Non-IBS |

IBS |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSRS-IBS total and Subscale Scores | All (n = 1158) | Non-IBS (n = 994) | p a | IBS (n = 164) | Non-GI– Consult (n = 495) | p b | GI-Consult (n = 493) | p c | Non-GI– Consult (n = 51) | p d | GI-Consult (n = 111) |

| Total score | 23.21 (10.07) | 21.14 (8.52) | g | 35.72 (9.69) | 19.06 (7.04) | g | 23.24 (9.33) | g | 32.65 (8.42) | f | 36.91 (9.91) |

| Diarrhea | 5.31 (3.16) | 4.76 (2.60) | g | 8.59 (4.13) | 4.38 (2.09) | g | 5.14 (2.96) | g | 7.59 (3.56) | e | 9.03 (4.29) |

| Constipation | 5.10 (3.23) | 4.74 (2.89) | g | 7.31 (4.17) | 4.31 (2.68) | g | 5.18 (3.03) | f | 7.04 (3.88) | 7.43 (4.34) | |

| Bloating | 6.04 (3.25) | 5.55 (2.96) | g | 9.02 (3.33) | 4.87 (2.44) | g | 6.24 (3.28) | g | 8.47 (2.93) | 9.15 (3.41) | |

| Pain | 3.85 (2.23) | 3.38 (1.87) | g | 6.70 (2.14) | 2.93 (1.48) | g | 3.84 (2.09) | g | 5.92 (1.83) | f | 7.02 (2.19) |

| Early satiety | 2.91 (1.71) | 2.71 (1.46) | g | 4.10 (2.46) | 2.57 (1.26) | f | 2.86 (1.62) | f | 3.63 (1.85) | 4.28 (2.66) | |

Non-IBS and IBS: absence and presence of Rome III IBS diagnosis. Non-GI–consult and GI-consult: absence and presence of previous consultation for abdominal complaints. The p columns indicate significant differences (ep < 0.05, fp < 0.01, gp < 0.001) in t-test comparisons of total and subscale scores according to superscript: aNon-IBS vs IBS; bNon-IBS Non-GI–Consult vs Non-IBS GI-Consult; cNon-IBS GI-Consult vs IBS Non-GI Consult; dIBS Non-GI–Consult vs IBS GI-Consult).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale–Irritable Bowel Syndrome (GSRS-IBS) total score among participants without and with an IBS diagnosis.

Distribution areas are not proportional to each other.

Discriminant validity

Comparisons between GSRS-IBS scores for different groups are displayed in Table 4. Participants with an IBS diagnosis had significantly higher total and subscale scores than participants without an IBS diagnosis. The further subdivision into treatment consulters and nonconsulters revealed increasing GSRS-IBS total and subscale scores that were significantly different between the four subgroups, with a few exceptions in which consulters and nonconsulters with an IBS diagnosis did not significantly differ on all subscales.

Table 5 shows scores on the GSRS-IBS subscales divided by the four IBS subtypes. As expected, participants with diarrhea-predominant IBS had the highest scores on the diarrhea subscale and participants with constipation-predominant IBS had the highest scores on the constipation subscale. There was no difference on the pain subscale between the constipation- and diarrhea-predominant groups; the mixed subtype had the largest pain subscale score (compared to diarrhea-predominant and unsubtyped IBS). Constipation predominance was associated with the highest scores on the bloating subscale, but only significantly larger when compared to unsubtyped IBS. The highest total score was found in the mixed subtype (compared to diarrhea-predominant and unsubtyped IBS) and the lowest score was observed in the unsubtyped group (compared to all other groups).

Table 5.

Means and SD on Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale–Irritable Bowel Syndrome total score and subscales for different irritable bowel syndrome subtypes.

| Constipation (n = 27) |

Diarrhea (n = 64) |

Mixed (n = 49) |

Unsubtyped (n = 24) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subscale | Mean (SD) | Diff | Mean (SD) | Diff | Mean (SD) | Diff | Mean (SD) | Diff |

| Total score | 37.37 (11.55) | Ua | 34.17 (8.43) | Mb Ua | 39.41 (9.79) | Db Uc | 30.46 (7.21) | Ca Da Mc |

| Diarrhea | 5.00 (2.67) | Dc Mc Ub | 10.34 (3.68) | Cc Ma Ub | 8.82 (4.23) | Cc Da | 7.50 (3.65) | Cb Db |

| Constipation | 11.26 (4.14) | Dc Ma Uc | 4.86 (2.52) | Cc Mc | 9.24 (3.90) | Ca Dc Uc | 5.46 (2.92) | Cc Mc |

| Bloating | 9.96 (3.64) | Ua | 8.81 (3.13) | 9.39 (3.32) | 7.75 (3.29) | Ca | ||

| Pain | 6.70 (2.37) | 6.47 (2.11) | Ma | 7.33 (2.13) | Da Ub | 6.00 (1.72) | Mb | |

| Early satiety | 4.44 (3.07) | 3.69 (2.04) | Ma | 4.63 (2.70) | Da | 3.75 (2.11) | ||

C: constipation predominant; D: diarrhea predominant; M: mixed subtype; U: unsubtyped.

Column “Diff” indicates significant difference (ap < 0.05, bp < 0.01, cp < 0.001) between a subtype and another subtype.

Convergent validity

Table 6 shows the means and SDs of the SF-36 subscales for participants with and without an IBS diagnosis. An IBS diagnosis was associated with significantly lower scores on all SF-36 subscales except physical functioning. The GSRS-IBS total score and subscales were negatively correlated with all SF-36 subscales. The largest GSRS-IBS total score correlations were observed with the energy/fatigue and pain SF-36 subscales (r = –.44) and the lowest GSRS-IBS total score correlation was with physical functioning (r = –.18). Overall, the GSRS-IBS pain subscale showed the largest correlations with SF-36 subscales and the early satiety subscale showed the lowest correlations.

Table 6.

Means and (SD) for SF-36 subscales for participants without and with a Rome III irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) diagnosis and correlations between Short Form Health Survey–36 items (SF-36) subscales and Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale–Irritable Bowel Syndrome (GSRS-IBS) total score and subscales.

| Rome III Diagnosis | Physical Function | Role Physical | Role Emotional | Energy | Well-Being | Social Function | Pain | General Health |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-IBS Mean (SD) | 91.65 (15.18) | 88.28 (26.40) | 87.29 (27.43) | 66.83 (21.30) | 79.67 (16.00) | 90.03 (18.05) | 85.03 (20.33) | 75.83 (17.81) |

| IBS M (SD) | 90.28 (16.31) | 75.00 (35.90) | 69.73 (39.51) | 50.89 (23.47) | 67.44 (21.36) | 76.86 (23.42) | 72.13 (20.94) | 63.90 (20.77) |

| p value | 0.314 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| GSRS-IBS correlations | ||||||||

| Total score | –0.18 | –0.29 | –0.28 | –0.44 | –0.38 | –0.39 | –0.44 | –0.38 |

| Diarrhea | –0.14 | –0.21 | –0.20 | –0.32 | –0.30 | –0.29 | –0.30 | –0.27 |

| Constipation | –0.12 | –0.20 | –0.21 | –0.29 | –0.24 | –0.26 | –0.29 | –0.25 |

| Bloating | –0.14 | –0.22 | –0.21 | –0.36 | –0.30 | –0.30 | –0.35 | –0.30 |

| Pain | –0.14 | –0.23 | –0.23 | –0.38 | –0.33 | –0.34 | –0.43 | –0.36 |

| Early satiety | –0.15 | –0.20 | –0.20 | –0.26 | –0.24 | –0.27 | –0.27 | –0.25 |

Non-IBS and IBS: absence and presence of Rome III IBS diagnosis. The p value row indicates statistical significance of differences in SF-36 subscale scores between non-IBS and IBS participants. All correlations are p < 0.001.

Discussion

In a population-based study, we assessed the psychometric properties of the GSRS-IBS, which is used to measure severity of IBS-related GI symptoms during the last week. We are unaware of any previous population-based data of this instrument. The present study showed that GSRS-IBS had adequate internal consistency, that total and subscale scores were significantly different between participants with and without IBS, and that treatment-seeking was associated with higher scores. Furthermore, the relevant subscale scores differed significantly between subtypes of IBS. The GSRS-IBS total and subscales were also correlated with the SF-36 subscales. Overall symptom severity and pain severity showed the largest correlations with the different quality of life domains, which is consistent with previous findings.22

The CFA largely agreed with the subscales proposed in the original GSRS-IBS article,4 with one notable exception. A factor structure that placed the Incomplete Emptying item in the constipation subscale rather than the diarrhea subscale showed markedly better model fit than the factor structure originally suggested by Wiklund and colleagues.4 Other studies that have studied symptom clusters in IBS have also reported that a recurring sense of incomplete emptying is related to constipation rather than diarrhea.19,20 Our analyses clearly suggest that the subscales of the GSRS-IBS should be changed accordingly.

The present study suggests that the GSRS-IBS can be used to reliably quantify IBS symptom severity in patients with IBS and the general population. The GSRS-IBS has several advantages compared to other self-rating scales of IBS severity. The PROMIS GI symptom scales23 have also been validated in the general population and cover the same symptom dimensions as the GSRS-IBS. However, the PROMIS GI includes 32 items that measure pain, gas/bloating, diarrhea, and constipation, whereas the GSRS-IBS is much shorter, comprising 13 items (of which two measure early satiety). Thus, the GSRS-IBS may be quicker to complete, which may be beneficial in treatment studies that often include multiple assessment points and other questionnaires.

One of the most widely used assessments of IBS symptom severity is the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Severity Scoring System (IBS-SSS).24 The IBS-SSS includes five items that measure severity and frequency of pain (number of days), severity of bloating, dissatisfaction with bowel habits, and life interference of IBS. Although the IBS-SSS items capture different and important aspects of IBS, it could be considered problematic to create a summary score of such diverse items. A summated rating scale should optimally measure a range of dimensions of one construct.25 A psychometric validation of the IBS-SSS showed that bowel movement dissatisfaction was more associated with the interference of IBS than the pain-related items.26 Provided that the IBS-SSS bowel movement dissatisfaction item measures the severity of diarrhea/constipation, this association could be interpreted as a stronger influence of diarrhea/constipation on disability than pain. However, our analysis indicated that the pain subscale of GSRS-IBS was more strongly associated with the different disability indices of SF-36 (see Table 6) than the diarrhea and constipation subscales. Our data suggest that the IBS-SSS dissatisfaction with bowel movement items may conflate the severity of diarrhea/constipation with disability. Thus, the IBS-SSS may not be an optimal measure of the severity of individual IBS symptoms, even when analyzing the items separately as suggested by Lackner et al.26

We observed clear associations between GSRS-IBS total score and treatment-seeking behavior, specifically a history of GI consultation, regardless of IBS diagnostic status. Among participants with an IBS diagnosis, only two of the GSRS-IBS subscales, pain and diarrhea, were significantly different between consulters and nonconsulters. The nonsignificant results at subscale level may be due to power issues, but previous research has also found that specifically pain and diarrhea are associated with treatment-seeking behavior in individuals with IBS.12 However, the relative importance of symptom severity as a predictor for health care–seeking in the IBS population has been questioned.12,27 We were not able to control for other potentially relevant factors, such as psychiatric comorbidity or quality of life, and future studies should investigate how these factors influence the relationship between IBS symptom severity and GI-specific, psychiatric and other health care–seeking behavior.

The results presented in this paper should be interpreted with a few limitations in mind. First, we did not have any criteria against which to validate the accuracy of the GSRS-IBS ratings, for example, daily diaries of the symptom severity in the week preceding the GSRS-IBS rating (which has a one-week recall period). Second, participants completed the GSRS-IBS only once, which precludes calculation of the test-retest reliability of the measure. Third, the norm data presented in the paper are based on the Swedish wording of the questions. Thus, the population means and SDs reported in this paper may not be directly applicable to other translations of the GSRS-IBS. Fourth, there was a slight participation bias in symptom burden in the younger strata in Popcol14 that may have influenced the overall score on the GSRS-IBS; however, this should not influence the psychometric calculations.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that the GSRS-IBS total score and subscales have adequate psychometric properties in terms of separating different relevant groups and associations with several aspects of quality of life. Together with previous studies indicating that the GSRS-IBS is sensitive to change, we conclude that the GSRS-IBS is an excellent measure of symptom severity in IBS.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the regional ethics committee in Stockholm on November 5, 2001 (No. 394/01). The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the regional ethics committee.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Stockholm County Council, Sweden; Ersta Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden; AstraZeneca R&D; and Mag-Tarmförbundet. AA had support from the Richard och Ruth Julin Foundation (2019-00370), Svensk Gastroenterologisk Forskningsfond, and Nanna Svartz Foundation (2017-00202). The study sponsors had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, or in the writing of the report.

Informed consent

All participants signed an informed consent.

ORCID iDs

Brjánn Ljótsson https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8086-1668

Michael Jones https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0565-4938

Anna Andreasson https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0203-7977

References

- 1.Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 1393–1407.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gralnek I, Hays R, Kilbourne A, et al. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology 2000; 119: 654–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford AC, Quigley EMM, Lacy BE, et al. Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies, including hypnotherapy, in irritable bowel syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109: 1350–1365; quiz 1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiklund I, Fullerton S, Hawkey C, et al. An irritable bowel syndrome-specific symptom questionnaire: Development and validation. Scand J Gastroenterol 2003; 38: 947–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Posserud I, Syrous A, Lindström L, et al. Altered rectal perception in irritable bowel syndrome is associated with symptom severity. Gastroenterology 2007; 133: 1113–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindfors P, Unge P, Arvidsson P, et al. Effects of gut-directed hypnotherapy on IBS in different clinical settings—results from two randomized, controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ljótsson B, Hedman E, Andersson E, et al. Internet-delivered exposure-based treatment vs. stress management for irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 1481–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunt M, Moshier S, Milonova M. Brief cognitive-behavioral internet therapy for irritable bowel syndrome. Behav Res Ther 2009; 47: 797–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ljótsson B, Hesser H, Andersson E, et al. Mechanisms of change in an exposure-based treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. J Consult Clin Psychol 2013; 81: 1113–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hesser H, Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Andersson E, et al. How does exposure therapy work? A comparison between generic and gastrointestinal anxiety-specific mediators in a dismantling study of exposure therapy for irritable bowel syndrome. J Consult Clin Psychol 2018; 86: 254–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schäfer SK, Weidner KJ, Hoppner J, et al. Design and validation of a German version of the GSRS-IBS—an analysis of its psychometric quality and factorial structure. BMC Gastroenterol 2017; 17: 139–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koloski N, Talley NJ, Boyce P. Predictors of health care seeking for irritable bowel syndrome and nonulcer dyspepsia: A critical review of the literature on symptom and psychosocial factors. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 1340–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longstreth G, Thompson W, Chey W, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006; 130: 1480–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kjellström L, Molinder H, Agréus L, et al. A randomly selected population sample undergoing colonoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 26: 268–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30: 473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care 1993; 31: 247–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drossman DA, ed. Rome II: The functional gastrointestinal disorders: Diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment: A multinational consensus. 2nd ed. McLean, VA: Degnon Associates, 2000.

- 18.Molinder HK, Kjellström L, Nylin HB, et al. Doubtful outcome of the validation of the Rome II questionnaire: Validation of a symptom based diagnostic tool. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009; 7: 106–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talley NJ, Holtmann G, Agréus L, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and subjects cluster into distinct upper and lower groupings in the community: A four nations study. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 1439–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crowell MD, Umar SB, Lacy BE, et al. Multi-dimensional Gastrointestinal Symptom Severity Index: Validation of a brief GI symptom assessment tool. Dig Dis Sci 2015; 60: 2270–2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schermelleh-Engel K, Kerwer M, Klein AG. Evaluation of model fit in nonlinear multilevel structural equation modeling. Front Psychol 2014; 5: 181–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cain KC, Headstrom P, Jarrett ME, et al. Abdominal pain impacts quality of life in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterology 2006; 101: 124–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spiegel BMR, Hays RD, Bolus R, et al. Development of the NIH Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) gastrointestinal symptom scales. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109: 1804–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francis C, Morris J, Whorwell P. The Irritable Bowel Severity Scoring System: A simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1997; 11: 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spector PE. Summated rating scale construction: An introduction, Newbury, CA: Sage Publications, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Baum C. Multidomain patient-reported outcomes of irritable bowel syndrome: Exploring person-centered perspectives to better understand symptom severity scores. Value Health 2013; 16: 97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gudleski GD, Satchidanand N, Dunlap LJ, et al. Predictors of medical and mental health care use in patients with irritable bowel syndrome in the United States. Behav Res Ther 2017; 88: 65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]