Oral cancers are increasing in the U.S. This brief calls on healthcare providers and legislators to expand awareness of risk factors, increase early detection, and support policies that increase utilization of dental services.

Keywords: Oral cancer, Oropharyngeal cancer, Early detection, Oral VTE

Abstract

In response to the increasing incidence of certain oral and oropharyngeal cancers, the Society of Behavioral Medicine (SBM) calls on healthcare providers and legislators to expand awareness of oral and oropharyngeal cancer risk factors, increase early detection, and support policies that increase utilization of dental services. SBM supports the American Dental Association’s 2017 guideline for evaluating potentially malignant oral cavity disorders and makes the following recommendations to healthcare providers and legislators. We encourage healthcare providers and healthcare systems to treat oral exams as a routine part of patient examination; communicate to patients about oral/oropharyngeal cancers and risk factors; encourage HPV vaccination for appropriate patients based on recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; support avoidance of tobacco use and reduction of alcohol consumption; and follow the current recommendations for evaluating potentially malignant oral cavity lesions. Because greater evidence is needed to inform practice guidelines in the primary care setting, we call for more research in collaborative health and dental services. We encourage legislators to support policies that expand Medicaid to cover adult dental services, increase Medicaid reimbursement for dental services, and require dental care under any modification of, or replacement of, the Affordable Care Act.

Implications

Practice: Healthcare providers should incorporate oral visual and tactile examination as a routine part of patient care, talk with patients about oral/oropharyngeal cancer, risk factors, and risk reduction, including human papillomavirus vaccination for eligible patients, and follow the American Dental Association’s guideline for evaluating potentially malignant or malignant oral cavity lesions.

Policy: Legislators and policy makers should support policies that expand Medicare and Medicaid to cover adult dental services, increase Medicaid reimbursement for dental services, and promote interdisciplinary healthcare delivery.

Research: Society of Behavioral Medicine encourages research to inform clinical practice guidelines including research in collaborative health and dental services to assess oral health.

BACKGROUND

In 2018, an estimated 51,540 new oral and oropharyngeal cancer cases will be diagnosed in the USA [1]. These are two distinct diseases, each with its own primary risk factors and prognosis. Cancer of the oropharynx involves the base of tongue, lingual/palatine tonsil, oropharynx, soft palate, uvula, and Waldeyer’s ring [2]. Cancer of the oral cavity, the primary focus of this discussion, occurs anterior to the oropharynx. In the U.S., 70%–80% of oral cavity cancer is associated with tobacco or heavy alcohol use [3], whereas human papillomavirus (HPV) is more likely to be associated with cancers of the oropharynx [5] rather than cancer found in the oral cavity [4]. Notably, significant differences in survival exist by HPV status. In an analysis of SEER data, 5 year relative survival for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer was 60.2%, compared with 45.6% in HPV-unrelated tumors [6].

Patients who survive oral/oropharyngeal cancer can face considerable morbidity. Surgery may remove major portions of the oropharynx, larynx, jaw, or tongue. Radiation therapy can damage skin, oral, and oropharyngeal mucosa and increase the risk of osteonecrosis of the maxilla or mandible. If radiation damages major salivary glands, the patient may develop xerostomia, rampant tooth decay, and increased risk of candidiasis [7]. Additional long-term functional issues can include difficulties with eating, swallowing, and speaking [8], as well as permanent disfigurement, chronic pain, and breathing difficulties [9–11]. As with all cancer, late detection of oral/oropharyngeal cancer is associated with increased risks of poor quality of life and of death [12, 13].

EARLY DETECTION

Oral visual and tactile examination (VTE) by trained clinicians can help detect malignant and premalignant lesions located in the oral cavity, floor of the mouth, and the ventral and lateral tongue, from which two-thirds of oral cancers arise [14]. Importantly, it is estimated that between 59 and 99% of these cancers can be detected using oral VTE [15].

Dental teams composed of dentists and dental hygienists routinely perform oral VTE [16–18]. However, up to one-third of U.S. adults do not receive regular dental care [19]. Medical providers can also perform oral VTE, but many do not receive adequate training. In a national survey of U.S. medical schools, 69% offered less than five hours of oral health education across the curriculum, and only 30% evaluated student knowledge of oral health topics [14].

A chief impediment to early detection of oral cancer is lack of access to oral healthcare. Barriers to access may include an underlying perception that preventive oral healthcare is not a priority [20–23]. Consequently, routine oral healthcare is underutilized by large segments of the U.S. population [24]. Furthermore, the U.S. delivery system does not provide sufficient levels of oral healthcare services, nor does it integrate oral health into the broader healthcare system [25].

ACCESS TO PREVENTIVE ORAL HEALTHCARE

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, fewer than two out of three adults aged 18–64 had seen a dentist in 2015, and these rates were below 50% for African- and Hispanic-Americans [26]. Lack of access to oral health services is partly attributable to a shortage of service providers. Recently, the Health Resources and Services Administration identified 5,866 Dental Care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) in the U.S. and estimated that more than 62 million people reside in HPSAs, leaving more than two-thirds of the dental workforce requirements in those populations unmet [24]. Additional factors influencing receipt of dental care include a perceived lack of need for preventive oral healthcare [20–23], lack of time and resources to travel to sites where care is available, and the high cost of care [19].

In addition, studies show that the public remains poorly informed about the relationship between systemic health and oral health. This may be particularly true for oral cancer and its associated risk factors [27–29]. The access-to-care literature suggests that systemic barriers to dental exam attendance must be addressed, and that the at-risk populations’ valuation of preventive oral health care must be heightened [30–32].

CALL FOR ACTION

Because late detection leads to higher adverse impacts on quality of life and greater risk of death [12], early detection and treatment of oral/oropharyngeal cancers are paramount.

The Society of Behavioral Medicine supports the 2017 American Dental Association’s expert panel recommendations and calls on healthcare providers and legislators to expand awareness of oral/oropharyngeal cancer risk factors and support policies that increase utilization of dental services.

AMERICAN DENTAL ASSOCIATION 2017 CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR DENTAL PROVIDERS

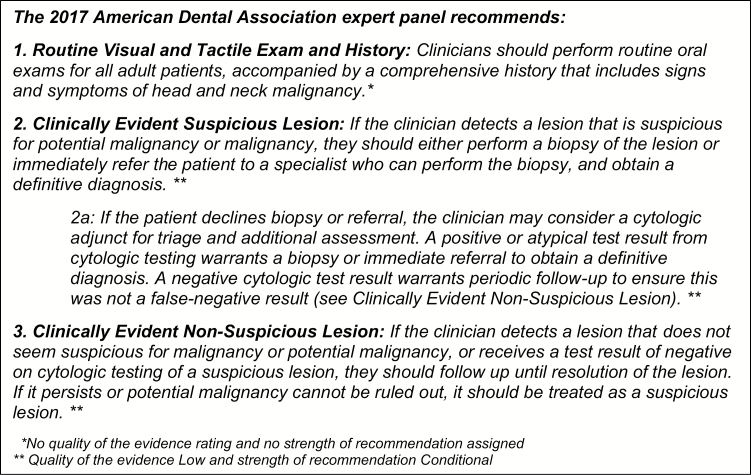

The American Dental Association (ADA) has developed a clinical practice guideline on the “Evaluation of Potentially Malignant Disorders in the Oral Cavity” (Fig. 1). This guideline was developed by an expert panel in collaboration with methodologists from the ADA’s Center for Evidence-based Dentistry [33]. It offers a good practice statement and six clinical recommendations, including when to perform oral VTE, when to perform a biopsy or refer to a specialist, and the diagnostic utility of various adjuncts (i.e., tests, technologies, and devices commercially available in the U.S.)

Fig. 1.

| Summary of American Dental Association Recommendations.

Their systematic review evaluated cytological, autofluorescence, tissue reflectance, vital staining, and salivary adjuncts as potential triage tools to be used following oral VTE. This systematic review and subsequent guideline were framed by clinical questions based on three types of adult patients: patients with no lesions, patients with clinically evident seemingly innocuous lesions; and patients with clinically evident suspicious lesions [33, 34]

The panel concluded that oral VTE should be performed in all adult patients. Biopsy with histopathological assessment should remain the gold-standard diagnostic test and is recommended for all suspicious lesions. Cytologic testing could be used to triage patients who refuse biopsy or referral for suspicious lesions, and for patients with persistent lesions that seem innocuous [33].

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

• National trends show increases in certain oropharyngeal cancers [1, 35, 36], mirroring increases in HPV infection [37]. Current prevention strategies, including HPV vaccination, are available. Clinicians should advocate for HPV vaccination and offer evidence-based tobacco dependence education and treatment to affected patients.

• Early diagnosis has been associated with regular dental visits [38]. Dentists and the oral health team have the experience and training to be effective in detecting disease at early stages. Recent efforts to expand the oral health workforce might also contribute to improve early detection.

• Available public policies can reduce identified barriers to care-seeking. Policy interventions at all levels, from reducing individual risk behaviors to providing comprehensive and integrated healthcare services, can improve oral healthcare delivery generally and directly support improvements in detection, diagnosis, and management of oral cancers [32]. Health policy to promote early detection should concentrate on making oral health services more broadly utilized.

• Expansion of dental insurance and reimbursement is warranted. Expansion could include requiring medical health insurance programs to cover oral health services. Improved reimbursements under publicly funded programs could encourage more dentists to participate in such programs.

• Although primary medical care providers can play a role in improving early diagnosis of oral cancer [39], their training generally does not prepare them for this role [40, 41]. Evidence suggests that efforts to train general medical clinicians to identify oral cancer can improve competence [42, 43]. Increasing education about oral anatomy and oral health in medical, physician assistant, and nursing curricula, as well as integrating dental care services into systemic healthcare settings has the potential to expand access to care and to increase early detection of oral cancer.

• Low awareness of oral cancer risk and the value of routine preventive care suggest a need for oral health promotion campaigns.

• Additional research is needed to inform clinical practice guidelines including research in collaborative health and dental services to assess oral health, patient history, physical exams, and counselling practices.

The ADA’s 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline is a key component in efforts to raise awareness of the early detection of oral cancer and precancerous lesions located in the oral cavity. The Society of Behavioral Medicine recommends that healthcare providers and legislators consider clinical and policy changes to reduce oral cancer incidence and increase early detection and utilization of oral health services, as follows.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR HEALTHCARE PROVIDERS

Dental care providers and primary medical care providers are key in efforts to reduce oral cancer incidence and to increase early detection of oral cancer and precancerous lesions. Providers should:

(1) Incorporate oral VTE as a routine part of patient care

(2) Communicate to patients about oral/oropharyngeal cancer and risk factors

(3) Encourage HPV vaccination for appropriate patients based on recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices [44]

(4) Support the avoidance of tobacco use and minimal alcohol intake

(5) Follow the ADA Guideline for evaluating potentially malignant or malignant oral cavity lesions [33]

(6) Strive to integrate oral and systemic healthcare delivery in clinical practice

(7) Support interdisciplinary training programs to promote dental and primary medical care integration

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR LEGISLATORS AND POLICYMAKERS

Legislators and policymakers can support policies to increase utilization of health services, including oral health services, specifically policies that:

(1) Expand Medicare and Medicaid to cover adult dental services

(2) Increase Medicaid reimbursement for dental services

(3) Require dental care under any modifications to the Affordable Care Act or replacement legislation

(4) Promote interdisciplinary care delivery through regulatory authorities and legislation

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to gratefully acknowledge the expert review provided by the Society of Behavioral Medicine’s Health Policy Committee, the Scientific and Professional Liaison Council, and the Cancer Special Interest Group. This project was supported by Grant Number 5R25-CA057699 from the National Cancer Institute and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest: The authors Caryn E. Peterson, Sara C. Gordon, Charles W. Le Hew, J. A. Dykens, Gina D. Jefferson, Malavika P. Tampi, Olivia Urquhart, Mark Lingen, Karriem S. Watson, Joanna Buscemi, and Marian L. Fitzgibbon have no conflict of interest to report.

Authors’ Contributions: All authors have contributed sufficiently to the scientific work.

Ethical Approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants and animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent: This study does not involve human participants and informed consent was therefore not required

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Osazuwa-Peters N, Simpson MC, Massa ST, Adjei Boakye E, Antisdel JL, Varvares MA. 40-year incidence trends for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in the United States. Oral Oncol. 2017;74:90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Radoï L, Luce D. A review of risk factors for oral cavity cancer: the importance of a standardized case definition. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41(2):97–109, e78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lingen MW, Xiao W, Schmitt A, et al. . Low etiologic fraction for high-risk human papillomavirus in oral cavity squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2013;49(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chesson HW, Ekwueme DU, Saraiya M, Watson M, Lowy DR, Markowitz LE. Estimates of the annual direct medical costs of the prevention and treatment of disease associated with human papillomavirus in the United States. Vaccine. 2012;30(42):6016–6019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jansen L, Buttmann-Schweiger N, Listl S, et al. ; GEKID Cancer Survival Working Group. Differences in incidence and survival of oral cavity and pharyngeal cancers between Germany and the United States depend on the HPV-association of the cancer site. Oral Oncol. 2018;76:8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Epstein JB, Barasch A. Oral and dental health in head and neck cancer patients. In: Maghami E, Ho A, eds. Multidisciplinary Care of the Head and Neck Cancer Patient. Cancer Treatment and Research, vol. 174. Cham: Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Noonan BJ, Hegarty J. The impact of total laryngectomy: the patient’s perspective. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(3):293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frowen JJ, Perry AR. Swallowing outcomes after radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Head Neck. 2006;28(10):932–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Callahan C. Facial disfigurement and sense of self in head and neck cancer. Soc Work Health Care. 2004;40(2):73–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang HL, Keck JF, Weaver MT, et al. . Shoulder pain, functional status, and health-related quality of life after head and neck cancer surgery. Rehabil Res Pract. 2013; (2013) 601768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ho AS, et al. , Metastatic lymph node burden and survival in oral cavity cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(31):3601–3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chandu A, Smith AC, Rogers SN. Health-related quality of life in oral cancer: a review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(3):495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferullo A, Silk H, Savageau JA. Teaching oral health in U.S. medical schools: results of a national survey. Acad Med. 2011;86(2):226–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Walsh T, Liu JL, Brocklehurst P, et al. , Clinical assessment to screen for the detection of oral cavity cancer and potentially malignant disorders in apparently healthy adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11(11):1–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Horowitz AM, Drury TF, Goodman HS, Yellowitz JA. Oral pharyngeal cancer prevention and early detection. Dentists’ opinions and practices. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131(4):453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Forrest JL, Horowitz AM, Shmuely Y. Dental hygienists’ knowledge, opinions, and practices related to oral and pharyngeal cancer risk assessment. J Dent Hyg. 2001;75(4):271–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gibson-Howell JC, Hicks M. Dental hygienists’ role in patient assessments and clinical examinations in U.S. dental practices: a review of the literature. J Allied Health. 2010;39(1):e1–e6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Association, A.D. Access to Care Available at https://www.ada.org/en/public-programs/action-for-dental-health/access-to-care. Accessibility verified March 5, 2018.

- 20. Listl S, Moeller J, Manski R. A multi-country comparison of reasons for dental non-attendance. Eur J Oral Sci. 2014;122(1):62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Melo LA, Sousa MM, Medeiros AK, Carreiro AD, Lima KC. Factors associated with negative self-perception of oral health among institutionalized elderly. Cien Saude Colet. 2016;21(11):3339–3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shane DM, Wehby GL. The impact of the affordable care act’s dependent coverage mandate on use of dental treatments and preventive services. Med Care. 2017;55(9):841–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Durham TM, King KA, Salama FS, Lange BM. Oral health outcomes in an adult dental population: the impact of payment systems. Spec Care Dentist. 2009;29(5):191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Workforce, B.o.H., H.R.a.S.A. (HRSA), and U.S.D.o.H.H. Services. Designated Health Professional Shortage Areas Statistics.First Quarter of Fiscal Year 2018 Designated HPSA Quarterly Summary As of December 31, 2017 Available at https://ersrs.hrsa.gov/ReportServer?/HGDW_Reports/BCD_HPSA/BCD_HPSA_SCR50_Qtr_Smry_HTML&rc:Toolbar=false. Accessibility verified March 3, 2018.

- 25. Harnagea H, Couturier Y, Shrivastava R, et al. . Barriers and facilitators in the integration of oral health into primary care: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Statistics, N.C.f.H. Health, United States, 2016 2016. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2016.htm#078 Accessibility verified February 28, 2018.

- 27. Osazuwa-Peters N, Tutlam NT. Knowledge and risk perception of oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer among non-medical university students. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;45:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McQuistan MR, Qasim A, Shao C, Straub-Morarend CL, Macek MD. Oral health knowledge among elderly patients. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146(1):17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Riley JL, Pomery EA, Dodd VJ, Muller KE, Guo Y, Logan HL. Disparities in knowledge of mouth or throat cancer among rural Floridians. J Rural Health. 2013;29(3):294–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Janz N, Champion V, Strecher V. The health belief model. In:Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley& Sons; 2002:45–66. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pyle MA. Conference Presentation: Changing perceptions of oral health and its importance to general health: provider perceptions, public perceptions, policyma ker perceptions. Spec Care Dentist. 2002:22(1):8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lingen MW, Abt E, Agrawal N, et al. . Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the evaluation of potentially malignant disorders in the oral cavity: a report of the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017;148(10):712–727.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lingen MW, Tampi MP, Urquhart O, et al. . Adjuncts for the evaluation of potentially malignant disorders in the oral cavity: Diagnostic test accuracy systematic review and meta-analysis-a report of the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017;148(11):797–813.e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peterson CE, Khosla S, Chen LF, et al. . Racial differences in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas among non-Hispanic black and white males identified through the National Cancer Database (1998-2012). J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(8):1715–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moore KA II, Mehta V. The growing epidemic of HPV-positive oropharyngeal carcinoma: a clinical review for primary care providers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(4):498–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Langevin SM, Michaud DS, Eliot M, Peters ES, McClean MD, Kelsey KT. Regular dental visits are associated with earlier stage at diagnosis for oral and pharyngeal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23(11):1821–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Crossman T, Warburton F, Richards MA, Smith H, Ramirez A, Forbes LJ. Role of general practice in the diagnosis of oral cancer. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;54(2):208–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mohyuddin N, Langerman A, LeHew C, Kaste L, Pytynia K. Knowledge of head and neck cancer among medical students at 2 Chicago universities. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134(12):1294–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Riordain RN, McCreary C. Oral cancer–Current knowledge, practices and implications for training among an Irish general medical practitioner cohort. Oral oncol. 2009;45(11):958–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. LeHew CW, Epstein JB, Koerber A, Kaste LM. Training in the primary prevention and early detection of oral cancer: pilot study of its impact on clinicians’ perceptions and intentions. Ear Nose Throat J. 2009;88(1):748–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hertrampf K, Wenz HJ, Koller M, Ambrosch P, Arpe N, Wiltfang J. Knowledge of diagnostic and risk factors in oral cancer: results from a large-scale survey among non-dental healthcare providers in Northern Germany. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014;42(7):1160–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination - updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(49):1405–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]