Nearly 85 years since von Willebrand disease (vWD) was first described, aspects of the definition and classification of the disorder remain a work in progress. The disease is widely regarded as being the most commonly inherited coagulation disorder, with a global prevalence of up to one person per 10,000. Physicians have long identified a wide variability in the severity and natural history of vWD.1 Currently, aspects of the framework for vWD categorization are being reorganized in light of the observed clinical heterogeneity, driven by an increasing understanding of the genetic basis for the molecular mechanisms that underlie the disease. Part of the importance of improving diagnostic precision lies in our limited ability to accurately predict the risk of bleeding of individuals affected by the disorder. This fact is particularly true for patients with borderline values of von Willebrand factor antigen (vWF:Ag) levels, most of whom fall within the current category of Type 1 vWD. Subcategories have long been recognized, but physicians and surgeons continue to struggle with the uncertainties of bleeding risk in a whole host of patients, which may lead to delayed procedures and inadequate or unnecessary therapy. With a broader perspective on vWF, we may consider that a more complete understanding of the pathophysiology of vWD and the further development of laboratory assessment of vWF function are important in the management of patients with common clinical conditions, many of which result in vWF abnormalities and abnormal coagulation.

Our difficulties predicting the risk of bleeding stem largely from limitations of modern laboratory techniques. Although invaluable in the diagnosis of vWD, typical vWD laboratory tests have problems with standardization, reproducibility, and temporal variability. These difficulties, coupled with the diversity of abnormalities that are inherent to the disease, have contributed to a vast literature with sometimes conflicting results and created significant confusion. The research use of molecular testing has been able to address some of the issues of ambiguity in diagnosis and is helping to elucidate genetic abnormalities at the root of vWD. Molecular diagnosis is shedding light into subclasses of the disease that had been anticipated and, as in other areas of medicine, may be close to becoming the definition of specific disease types. However, gene properties and the sheer number of genetic abnormalities associated with vWD have impaired our ability to develop a simple and practical molecular classification. Through the painstaking process of genotypic/phenotypic correlation and the further characterization of bleeding risk, we can begin to fine-tune our diagnostic approach to maximize the clinical utility and begin to develop a more complete view of the mechanistic and genetic basis for abnormalities in vWF.

PHYSIOLOGY OF VON WILLEBRAND FACTOR

von Willebrand Factor Form and Function

A mechanistic description of the pathology of vWD requires knowledge of the role of vWF in coagulation and the structural basis for its function. This role can be described from a conceptual point of view as a form of mechanochemical transducer converting vascular damage into activation of coagulation. In simple terms, the process begins with damage to endothelial cells exposing underlying collagen (Fig. 1). Because vWF exists in circulation as a multimer of vWF dimers, it has the flexibility to form extended string-like forms when subjected to high shear rates (approximately > 2000/s).2,3 The vWF becomes anchored to the subendothelial collagen, and this large multimer is twisted and stretched by shear stresses from the overlying flowing blood. In the laminar flow profile of blood, red blood cells tend to be more concentrated in the central portion of vessels, pushing platelets toward the margins. This allows extended vWF to reach out and grab flowing platelets, taking hold of platelet membrane glycoprotein Ibα (GPIbα) molecules through the vWF-A1 domain. The GPIbα interaction has a relatively high rate of turnover, which allows the platelet to essentially roll from vWF molecule to vWF molecule.4 The tethered platelet can become stabilized by stronger binding to vWF and coming into direct contact with the subendothelial collagen through activated receptors α2β1 integrin andglycoprotein GPVI.5 The binding process then results in a conformational change on the important glycoprotein GPIIb/IIIa (also known as integrin αIIbβ3), allowing further binding to vWF and fibrinogen.6 The resulting chain reaction of continued platelet and coagulation factor cascade activation culminates in thrombin production, fibrinogen splitting, and the formation of a platelet/fibrin clot. vWF also participates in these other steps by serving as the carrier protein of the essential coagulation protein factor VIII. Through its binding of factor VIII, vWF acts as a “fight ready” clotting factor reserve that can be made available quickly at a site of injury. Although there is a buffering aspect to this factor VIII binding, the vWF role as a factor VIII carrier is predominantly passive.

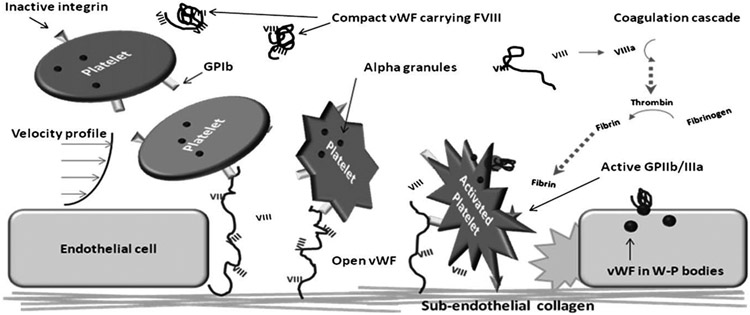

Fig. 1.

Overview of vWF function. Circulating inactive platelets are loosely trapped by collagen-bound vWF that has stretched in response to the shear stresses at endothelial cell injury sites. The platelets roll atop vWF molecules and undergo shape-change and activation, which allows the platelets to bind collagen directly through integrins. The factor VIII carried on vWF can then interact with the coagulation cascade to promote the generation of thrombin and eventually fibrin strands. The newly formed fibrin can then crosslink platelets through the activated GPIIb/IIIa receptor, forming the basis for a platelet-fibrin clot.

From Gene to Protein

The gene structure of vWF is relevant in terms of molecular characterization of the disease and explaining the difficulties associated with developing genetic testing for screening and diagnosis. Located on chromosome 12p13, the vWF gene is large—spanning 178 kb and consisting of 52 separately expressed regions. The vWF gene product (2813 amino acids) is composed of a 22 amino acid signal prepeptide and a 741 amino acid propeptide (vWFpp) located at the N-terminus of the mature 2050 amino acid vWF subunit. Frequent and nonrandomly distributed cysteine residues provide anchors for dimerization later in processing. The pro-vWF, composed of the vWFpp and mature vWF subunit, is arranged into structural domains with sequence and functional homology to well-characterized protein motifs. They are labeled linearly as D1-D2-D′-D3-A1-A2-A3-D4-B1-B2-B3-C1-C2-CK (Fig. 2). The multifaceted functions of the mature vWF can be attributed to these structural domains, and mutations within these conserved regions often explain the observed phenotypes.

Fig. 2.

The domains of vWF protein. Motifs correspond to specific vWF functions. The pre-vWF fragment is not shown (1–22), but the current standard amino acid naming convention begins at the first portion of the prepeptide.

vWF is synthesized in endothelial cells and megakaryocytes in a process that includes extensive postsynthesis modification.7,8 After directed transport to the endoplasmic reticulum, there is uncoupling of the prepeptide signal sequence and initial glycosylation. The propeptide chaperones dimerization of the vWF subunits through disulfide bonds within the C-terminal CK-domain.9 The glycosylation and dimerization precede the subsequent transport to the Golgi apparatus and linkage of the dimers via disulfide bonds near the amino terminal ends. This process yields a distribution of vWF multimers, primarily composed of the largest molecules, including some with more than 40 dimers and a molecular weight of more than 20 MDa.10,11 vWF is further sulfated and glycosylated within the Golgi. The propeptide is removed during the dimerization process within the trans-Golgi compartment, remains loosely associated to the assembled vWF, and along with other microenvironmental factors (such as pH) is responsible for storage of vWF into platelet alpha granules and the Golgi-derived Weibel-Palade bodies of endothelial cells.12 The vWFpp, permanently dissociated from mature vWF after secretion, is also released into circulation in a 1:1 ratio with each vWF monomer. A relatively short half-life (2 hours) contributes to a circulating concentration one-tenth that of multimerized vWF (1 μg/mL versus 10 μg/mL).13,14

Constitutive and secretagogue-dependent vWF release pathways have been extensively studied, but the precise signaling cascade mediating the distribution and trafficking of vWF is incompletely understood. The Weibel-Palade bodies are regulated storage vesicles and, as such, are convincingly implicated in the secretagogue-dependent release. Recent evidence also points to steady state, delayed, basal secretion through Weibel-Palade bodies to be the primary means of vWF release into the circulation.15 Megakaryocytes are not believed to contribute significantly to this steady-state vWF level and platelet vWF in alpha granules is mainly of low multimer number.16 A significant reserve is present in endothelial cells and the secretagogue-mediated granule exocytosis releases multimers that are larger and more biologically active than those released via the constitutive pathway.

Population-based reference ranges for plasma vWF are broad, and individual subjects show considerable variability on repeat testing because of the complex genetic and environmental factors regulating expression of vWF.17 Within the normal population without a bleeding diathesis and wild type vWF gene, blood type is the single most important qualifier of baseline vWF. vWF release, however, contributes only part of the “steady state” vWF level and multimer distribution.

von Willebrand Factor Multimers, Degradation, and ADAMTS-13

The largest mature vWF multimeric structures have the capability to extend to 2 μm, making it the largest human plasma protein, but it is further modified as it enters the circulation. Initially secreted as ultra-large multimers reaching 80 monomers large, the metalloproteinase ADAMTS-13 cleaves these molecules at a specific aminoacid junction (Y1605-M1606) in the A2 portion of any of the exposed units. It produces a distribution of multimers down to dimer form with a molecular weight of 556 kD. ADAMTS-13 has received a great deal of attention lately with the recognition that anti-body-mediated inhibition of this protein is the cause of nonfamilial thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura (TTP). Diagnostic tests to assess its activity and its inhibitors have evolved. In normal patients, the higher functionality of larger multimers likely relates to an increased ability to extend under shear stresses and longer reach available for platelet trapping. Degraded products are removed from circulation via as-yet-unclear mechanisms, but it seems to be related to the expression of H antigens on the multimers and is independent of multimer size.18 Intermediate degradation products correspond to dim bands that appear between bright bands in intermediate- or high-resolution gel electrophoresis (see the section on multimer analysis; Fig. 3). The net distribution of multimers achieves a “steady state” when the balance of synthesis, secretion, degradation, and removal is reached. The relative kinetic rates of these steps define the total concentration and relative distribution of vWF multimers in peripheral blood. Normally, the distribution is such that most vWF dimers exist in intermediate multimer form. Alterations in any of these steps lead to the range of multimer abnormalities detected on gel electrophoresis.

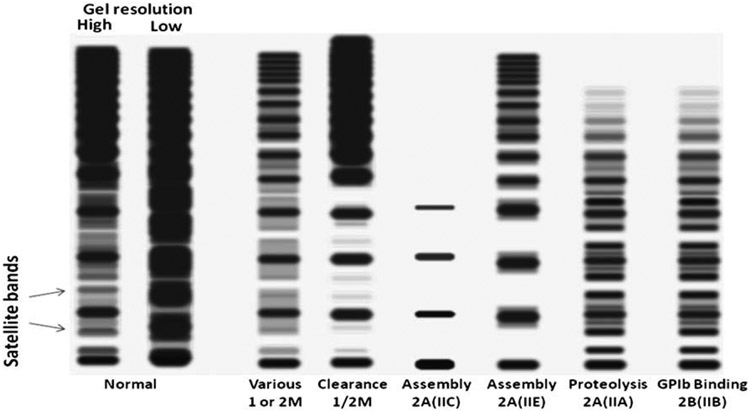

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of representative vWF multimer gels. Low-resolution gels show a distribution of multimers and are able to resolve broad patterns of small, intermediate, and large multimers. Higher resolution gels are needed to visualize satellite bands representing degradation products and flank main multimers. Various patterns are characterized predominantly by the main features of total intensity, distribution of sizes, and abnormalities of the satellite bands corresponding to different molecular mechanisms as discussed in the text.

Response to Desmopressin

Endothelial cells are the specific source of rapid increases in vWF in response to the therapeutic agent desmopressin (DDAVP). DDAVP is a vasopressin analog that stimulates secretion of vWF, vWFpp, and factor VIII, apparently through a V2-receptor and cAMP mediated activation of endothelial cells.19 It is often used as a diagnostic/ therapy-evaluation tool. A standard challenge protocol involves a baseline measure of vWF:Ag and vWF:ristocetin cofactor (RCof) and/or vWF:collagen binding (CB) levels, with a measure of the same tests 1 hour after infusion of 0.3 μg/kg body weight of DDAVP. A 4-hour measure is sometimes also obtained for clearer determination of half-life. Therapeutically, similar levels are used. Most (but not all) type 1 patients respond with normalization of levels of all tests at 1 hour. Few type 2 and no type 3 patients normalize. Some type 1 patients respond with supranormal levels of antigen and activity. Other type 1 patients have partial responses; at the Yale-New Haven Hospital laboratory, we consider 1-hour post-DDAVP levels that remain less than 75 IU/dL as a suboptimal response. Levels that remain less than 50 IU/dL we deem as abnormal responses, which may correspond to type 2 and type 3 patients. The weakly responsive type 1 patients also may require factor replacement therapy to prevent more serious bleeding complications with even minor trauma. These findings usually indicate characteristic molecular abnormalities (see later discussion). Although the DDAVP challenge is generally considered to be safe, there is significant cost and it is not without risks; hence, attempts at developing alternative methods for identification of nonresponders, such as the vWF propeptide to vWF antigen ratio and spectroscopic multimer measurements, which are discussed in the laboratory testing section.

VON WILLEBRAND’S DISEASE CLASSIFICATION: CONCEPT EVOLUTION

Excessive bleeding with minor trauma is one of the principal presenting symptoms of von Willebrand disease of all types. The severity and initial presentation, however, are highly variable, reflecting the broad pathophysiologic heterogeneity. Inherited forms with strong penetrance and forms with severe symptoms are more easily recognized. Even von Willebrand himself, aside from describing clinical and genetic characteristics that make vWD distinct from hemophilia A, noted the variability in clinical behavior within the broader disease category. As with any diagnostic evaluation, the goal in investigating a chief complaint of excessive bleeding is disease classification as a means to better predict the natural history of—corresponding to the need for and potential effect of— therapeutic intervention. An early formal attempt at classification in vWD was published in 1987 by Ruggeri and Zimmerman.20 It used the traditional three-category system: initially designated by roman numerals and limited to just type I (partial quantitative deficiency and type II) qualitative deficiencies, with the subsequent addition of a type III (absence of vWF protein). The classification originated from the compilation of published reports of vWD variants as characterized mainly by patterns on agarose gel electrophoresis. This initial effort was a great step forward in disease classification but had significant drawbacks, primarily that new variants were quickly identified that did not fit well within categories and that the complexity was such that it became unwieldy for practicing physicians. These problems were compounded by the difficulties associated with gel electrophoresis, which made it (and to a large degree still do) impractical as a routine diagnostic test. It illustrates the early recognition that the three subtype classification system is a gross simplification of the variety of disease mechanisms.

With the further development of ristocetin-based functional tests for vWD and to address the limitations of the 1987 effort, a new classification was published in 1994 by Sadler21 that simplified the categorization into the three main types and four type 2 subcategories: 2A, 2B, 2N, and 2M, all of which are still in use. Type 1 and type 2 vWD and the subtypes were determined on the basis of total vWF antigenic level (vWF:Ag) and ratios of vWF:Ag to vWF:RCof and low-resolution gel electrophoresis patterns. The conceptual framework is that the principal clinically important distinctions to be made are overall risk of bleeding and responsiveness to DDAVP. Most cases of vWD are mild forms that tend to have mild to moderately decreased antigen levels, proportionally decreased RCof activity levels, a normal distribution of multimers, and good response to therapeutic administration of DDAVP. These “type 1” cases should be distinguished from the more severe type 2A cases that generally have disproportionately low activity levels corresponding to lack of more functionally active large multimers. Types 2B, 2N, and 2M represent special cases with the specific mechanisms of increased binding to GPIb on platelets, impaired factor VIII binding mimicking hemophilia, and impaired binding to GPIb, respectively. Severe cases of vWD fall into the “type 3” category, which manifest as nearly complete absence of vWF. Outside this simplified framework lies pseudo-vWD, which represents a defect in the GPIb molecule on the platelets rather than on the vWF protein, and acquired vWD, which results from antibody formation directed toward the multimeric protein and other mechanisms related to increased clearance. The originally designated Vincenza type of vWD, characterized by increased clearance of multimers, has been variably classified as type 1 and type 2M.

This simplified scheme has survived for 15 years with minor adjustments described in a 2006 update from the Working Party on vWD Classification of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, which maintained the categories as defined in 1994 but broadened the definition of type 1 to include small abnormalities in multimer patterns and eliminated the restriction to mutations in the vWF gene.22 In practical terms, this allows for the clinical designation of type 1 vWD in patients with a history of excessive bleeding and low vWF for whatever combination of reasons. Limitations remain. An important aspect is the heterogeneity in mechanism, bleeding risk, and DDAVP responsiveness of cases labeled as type 1, type 2A, and type 2M. Another is the demarcation between individuals with low but hemostatic levels of vWF and individuals with true type 1 vWD. As molecular information gets correlated with the various subtypes described, additional clues are acquired that can help us further stratify risk and responsiveness. What is certainly becoming clear is that multiple factors contribute to overall bleeding risk in vWD.

LABORATORY TESTING METHODS

Identifying methods to accurately and reproducibly monitor vWF activity and stratify bleeding risk has been a primary goal of clinical laboratory testing and research for decades. Reproducing the complexity and in vivo requirements of vWF-mediated coagulation in the laboratory has been a stumbling block for accurate diagnosis and classification, however. Many of the testing assays and platforms depend on nonphysiologic intermediaries that can somewhat effectively recapitulate portions of the in vivo microenvironment. Although the current phenotypic working classification is not tied to specific testing platforms, a discrete panel of readily available assays usually can discriminate between the broad subtypes of vWD. These classic assays, including vWF antigen (vWF:Ag), vWF activity (vWF:RCof), and factor VIII, also enjoy the added benefit of uniform sample requirement (citrated platelet poor-plasma) and can be ordered retrospectively on samples previously drawn for standard coagulation prolife testing (PT/INR,PTT). Additional testing is often required for further clinically relevant subclassification, particularly for type 2 disease. This discrimination usually can be achieved with multimer gel electrophoresis. Low-resolution gels are most often used, but higher resolution gels can reveal more subtle abnormalities that are recognized to have clinical implications. Unfortunately, gel methods are laborious and difficult to perform reproducibly, which makes them impractical for many laboratories. They remain in many ways the gold standard for vWD evaluation.

Two tests have become more frequent in the initial evaluation and monitoring of vWD, both designed to improve on vWF:RCof as a functional screen for the characterization of type 2 defects. One is the collagen binding assay (vWF:CB) and the other is the platelet functional analyzer (PFA-100) clotting time. The vWF:CB has demonstrated increased sensitivity to large multimers and has proven itself at least as a useful adjunct to the traditional tests. The PFA-100 has shown utility as a substitute to the unwieldy bleeding time. (See the article by Tormey and colleagues, elsewhere in this issue.) As we gain clinical experience with the use of these tests, we will be better able to define their role. Like traditional tests, however, they have fundamental limitations.

The ever-increasing list of available tests for vWF assessment can help classify and stratify risk but also can contribute to the confusion that surrounds typing systems, particularly because they may have unpredictable results in some of the less common variants of this very heterogeneous disorder and because they do not incorporate the genetic mutation information that is accumulating. Still, with an understanding of the basic principles underlying the various tests, it becomes possible to interpret results in light of this growing body of genotypic and mechanistic knowledge.

von Willebrand Factor Antigen

Several methods are in general use for the determination of total vWF antigen concentration. The two principal techniques that have supplanted the traditional Laurell immunoelectrophoresis are a bead aggregation immunoturbidometric assay (Dade Behring and Stago) and enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based systems using a variety of commercially available antibodies (Abs). The turbidity assay measures the increase in bead-affected turbidity that results from the antibody mediated clumping of Ab coated beads when cross-linked by vWF. Immunosorbent assays are most often sandwich-based methods that have wells coated with vWF antibody; plasma levels are detected with either enzyme-linked colorimetric or fluorescence-linked anti-vWF antibodies. The levels are calibrated with pooled standards derived from more than 200 donors designated as 100 IU/dL by the World Health Organization (WHO) International Standards and correspond to a normal percentage of 100%. All the methods demonstrate relatively good intra-assay and interassay reproducibility on quality assurance surveys, certainly better than activity measures, but variable sensitivity to clinical interference, such as with rheumatoid factor, in bead-based tests has been described.23

Specific aspects to consider when interpreting vWF:Ag values are discussed in the section on diagnostic issues and include blood type variability, reactive increases, and disease threshold values. It is worth noting that the WHO standard itself has had problems of drift over successive evaluations resulting in a revaluation of the international unit standard in 2001.24 In general, however, bleeding risk correlates with antigen level and so values should be somewhat interpreted as a marker of bleeding propensity regardless of cause.

von Willebrand Factor: Ristocetin Cofactor Activity

Ristocetin is an actinomycete-derived antibiotic initially used in the treatment of staphylococcal infections in the early 1950s, which unexpectedly induced several hematologic complications, including thrombosis. It induces platelet aggregation via vWF-GPIbα interaction that depends somewhat on the larger, more biologically active vWF multimers. The ability of ristocetin to induce platelet-vWF-dependent platelet aggregation in vitro has been exploited in the laboratory setting. The vWF:RCof assay is based on the capacity of plasma vWF to agglutinate formalin fixed reagent platelets in the presence of ristocetin. This differs from the platelet aggregation ristocetin test, which uses the patient’s native unfixed platelets and is much more susceptible to inadvertent activation and spurious results. Similar to the platelet aggregometry ristocetin test, however, comparison of serially diluted patient plasma aggregometry profiles to normal/reagent plasma aggregometry profiles using the fixed platelets provides a quantitative estimate of vWF activity, most frequently expressed as a percent of normal, calibrated to international units per deciliter. As such, calibration curves are critically important, and because of the intrinsic variability of the agglutination, accuracy depends on the number of repeats on a given sample. As expected, inter- and intra-assay variability is high, and the WHO international standard has seen excessive variations on successive measurements, resulting in revaluation.24

When interpreted in the context of vWF:Ag and factor VIII level, however, vWF activity testing provides a reasonable stratification of most patients within the traditional phenotypic classification of vWD. In patients with type 1 disease (accounting for most cases), there is a proportional decrease in vWF:RCof and factor VIII level with respect to vWF:Ag. This relationship can be numerically expressed as a ratio of vWF:RCof/vWF:Ag, with values more than 0.7 (close to 1.0) highlighting the quantitative deficiencies (type 1) and ratios less than 0.7 suggesting qualitative defects (type 2). These findings are particularly relevant in classic type 1 disease. Unfortunately, when antigen or activity levels fall into the 20 IU/dL range or below, the ratios become less reliable indicators of multimer size distribution. Multimer analysis (or potentially the collagen binding assay) is nearly always needed for confirmation. It has also been proposed that ratios between 0.5 and 0.7 may be seen in both types, especially with some of the less sensitive cofactor activity assays, and that specificity for type 2 occurs only below 0.5. Regardless, activity measurements also can be measured after DDAVP administration to monitor efficacy and help in the classification of some rarer variants. It should be noted that this assay does not account for plasma antigenic concentration of vWF, and decreased activity is noted in qualitative and quantitative vWF deficient states. Additional testing on a separate platform is necessary for a complete initial evaluation, including vWF:Ag and factor VIII in cases with a decreased cofactor activity.

Relatively recently, an assay was introduced comprised of a fully automated latex agglutination-based system that is commercially available.25-27 The HemosIL VWF Activity assay (Instrumentation Laboratory, Lexington, Massachusetts) uses latex particles conjugated to monoclonal antibodies directed against the vWF GPIbα binding site. The activity of vWF to bind the latex beads is proportional to the turbidity of solution measured by standard spectrophotometric means. Direct comparison of this assay with vWF:RCof shows excellent concordance; however, additional testing either by classic ristocetin aggregometry or other functional testing may be warranted for confirmation of abnormal results. As with the analogous antigen assay, some falsely elevated levels may be seen in the presence of autoantibodies to rheumatoid factor, and absolute values tend to be higher than with the conventional agglutination assay.

A recombinant GPIbα-based ELISA assay also has been introduced. A variant uses a sandwich antibody conformation, with one Ab recognizing a bound conformation of recombinant GPIbα for capture and a polyclonal Ab for detection.28 The assay is run under conditions of artificial ristocetin stimulation and levels depend on antigen concentration, but the activity-to-antigen ratio using this ELISA-based assay seems to have excellent sensitivity for deficiencies of high molecular weight multimers and reportedly lower coefficients of variation than agglutination based assays. As more clinical experience is acquired, its overall utility will become clearer.

Multimer Analysis (Gel Electrophoresis)

With all its limitations, the gold standard in determining vWF multimer distributions remains gel electrophoresis. Unfortunately, the difficulties associated with this type of testing severely limit its use. The technical challenges lie in creating reproducible vWF multimer patterns, which makes calibrated quantitative determinations virtually impossible. A standard method for multimer analysis involves preparation of 1% to 1.2% (low resolution) or 1.5% to 2% (intermediate resolution) SDS-agarose gels with electrophoresis for approximately 16 hours, followed by anti-vWF antibody-coated nitrocellulose filter electroblotting, washing, and radiolabeled or enzyme-linked second antibody-based detection of bands.29,30 Several variations exist, including techniques that speed up and improve reproducibility of gels, but in general the test is laborious and time-consuming and suffers from numerous sources of variability, including gel thickness, homogeneity, heat and evaporation, current fluctuation, blotting efficiencies, and detection exposure. As a result, typically only reference laboratories offer the test on a routine basis, usually with turnaround times of a week or more, and they report only qualitative interpretations.

Multimer analysis by gel electrophoresis provides valuable diagnostic information. At its simplest, low resolution, gel electrophoresis can identify gross abnormalities in the distribution of multimers, as would be expected in most types 2A, 2B, and 3 of vWD. These figures can be contrasted with the more normal distribution expected in types 1 and 2M. As illustrated in Fig. 3, intermediate- and high-resolution gels have the added capability of identifying abnormalities that arise from specific mechanisms that directly relate to bleeding risk. Many of these result in abnormalities in the socalled “satellite bands,” which represent the asymmetric degradation products of ADAMTS-13 activity. Normally, low-resolution gels can identify the smallest 556 kD homodimer and show multimer separation up to approximately 10 to 15 dimers. Higher resolution gels can resolve the satellite bands from at least the 2- to 6-mers, which may be decreased, increased, or of abnormal size/mobility as a result of the specific mechanistic defect in vWF synthesis or metabolism. The use of this technique for identification of subtle abnormalities that correspond to polymorphisms or frank vWD mutations seems to be on the rise and may be increasingly helpful in the future for stratification of risk and therapy as more of these defects are correlated with clinical and genetic information. (See the section on mechanistic classification.)

Collagen Binding Assay

The assessment of the ability of vWF to bind collagen as a functional assay was first reported more than 20 years ago. The current favored procedure involves a standard sandwich ELISA with collagen coated wells for capture and polyclonal anti-vWF for labeling and detection. Controversy over the relative sensitivity of the various forms of this assay has affected support of its use. The conflict stems mainly from the observation that type III collagen, as first used, seems to bind relatively indiscriminately to multimers of all sizes, whereas a combination of types I and III collagen in an approximate proportion of 19:1 seems to be much more selective for only the largest multimers.31 It is this latter mixture that is deemed as having the best ability to sensitively and specifically identify abnormalities in the distribution of multimers. Unfortunately, the commercial collagen-binding assays available remain restricted to type III collagen, which, in purified form, seems to still have discriminatory advantage over the RCof assays in detecting relative decreases in large multimers, only not sufficient to warrant replacement of gel multimer evaluation. Home-brewed assays using the collagen combination are likely to be superior when properly validated. A remaining area of contention is the behavior of this assay in patients with type 2M, which is reportedly either low or borderline in most cases. This may reflect ambiguities in type 2M diagnosis itself.

Monitoring the response of vWF:CB to DDAVP administration also has been proposed for determination of the appropriateness of therapy and the potential need for factor replacement.32 Additional data would be helpful in confirming the clinical utility of this approach. What does seem rather clear is that laboratories vary in their ability to distinguish between types 1 and 2 of vWD and that the RCof/Ag ratio and even gel electrophoresis (especially low resolution) may not be sufficiently sensitive or specific.31 It is likely that there could be improvement with the incorporation of a well-validated collagen binding assay as part of the repertoire of vWF testing tools.

Platelet Functional Analyzer-100 in von Willebrand Disease

The PFA-100 was introduced in 1995 by Dade-Behring as a simple, more practical and rapid substitute method for the cumbersome bleeding time traditionally used as a screening test in the evaluation of platelet function.33 In principle, the PFA-100 closure time is a measure of overall ex vivo platelet-based coagulant function. A PFA-100 cassette contains a membrane coated with the platelet activators collagen and epinephrine or collagen and ADP that stimulate platelet activation. On this membrane is a small orifice (150 μm) through which citrated whole blood is aspirated, creating a high shear stress that more closely simulates in vivo conditions for vWF-related platelet tethering and clot formation. The amount of time from flow start to occlusion is a measure of overall platelet function (clotting time). Time is measured in seconds, and normal ranges are generally recommended to be determined at a given laboratory. This latter property is especially important because there are no whole blood control samples available for calibration. For the Yale-New Haven Hospital laboratories, the normal ranges are 80 to 180 seconds for collagen and epinephrine and 60 to 110 seconds for collagen and ADP, which fall within the distribution of normal ranges reported in other laboratories.34 Values more than 300 seconds are reported as “nonclosures.” As is typical of platelet function assays, low platelet counts and aspirin use affect results, and care must be taken in specimen preprocessing so as to avoid inadvertent premature platelet activation. The PFA-100, however, is far more robust than traditional aggregometry because samples need not be drawn immediately next to the analyzer and sample preparation is minimal.

The platelet activation measured in response to agonists depends on vWF binding to GPIbα. Like other platelet function tests, PFA-100 closure time depends on adequate amounts of functional vWF. In principle, the PFA-100 closure time has been shown to be sensitive as a screening and diagnostic tool in vWD. Under real testing conditions, however, the sensitivity drops somewhat and is estimated to be 85% to 90%.34 A criticism of the use of PFA-100 in screening, particularly as it pertains to type 1 diagnoses, is that closure time correlates rather closely with vWF:Ag levels and that the antigen levels tend to be more reliable. The closure time also has been correlated to age, blood type, and a variety of other clinical states, but it is unclear how much of this correlation is related directly to vWF levels. The specificity depends greatly on the clinical indication for the test (pretest probability), although this becomes less important for screening or monitoring therapy.

Studies also indicate that the PFA-100 closure time is most sensitive to high molecular weight multimers, likely reflecting the relative importance of these large multimers in vivo. This feature is shared by the other vWF functional tests, namely vWF:RCof and vWF:CB assays. Of these, the latter is the more sensitive to high molecular weight multimers. The PFA-100 is simpler to perform and less labor intensive with a comparable sensitivity, however. Unfortunately, in our laboratory’s experience, sample platelet/preprocessing sensitivity reduces reproducibility and causes occasional unsatisfactory specimens. The lack of reliable and readily available standardized control material limits confidence in results. By comparison, our long experience with RCof activity counter-balances it’s shortcomings of the PFA-100. It would be considered highly unusual for a patient with type 2 or type 3 vWD to have a PFA-100 closure time within the normal range, although there are a few reported instances for some type 2 patients. Currently, clinicians at our institution use both functional tests on a regular basis.

From a monitoring point of view, the PFA-100 has some characteristics that make it clinically useful, likely related to its high molecular weight multimers bias. Post-DDAVP testing shows correlation between what is loosely considered therapeutic by antigen methods and the correction of closure time. This is particularly true in type 1 patients who often respond to DDAVP infusions. In a recent article by van Vliet and colleagues,35 discrepancies were found between correction of values in type 2 postfactor VIII/vWF concentrate patients using RCof and CB assays versus PFA-100 results. The speculation is that this reflects a higher sensitivity of the PFA-100 to high molecular weight multimers, allowing this method to detect potentially clinically important deviations from the normal multimer size distribution. Although the sensitivity of the specific vWF:CB assay used in this study is not clear, testing of all parameters post-DDAVP is likely to yield clinically useful information. Additional studies confirming the clinical relevance are needed.

Platelet Aggregation (Low- and High-dose Ristocetin)

As in the ristocetin-induced activity plasma-based assay, ristocetin can be used to induce the patient’s own platelets to aggregate. The additional challenge in this test is that platelets are exquisitely sensitive to inadvertent activation and do not withstand storage and transport well. The test must be performed with the patient near the instrument so that the sample can be tested immediately. The procedure itself is relatively straightforward and involves mixing patient platelet-rich plasma with ristocetin and monitoring turbidity. As platelets agglutinate, turbidity increases and a characteristic curve with high-dose ristocetin results in decreased light transmittance over the course of minutes. When there is a defect in GPIbα and vWF-mediated platelet agglutination, transmittance is preserved to some degree. The RCof assay using a standardized formalin-fixed platelet reagent serves this purpose better. The PFA-100 also can test overall GPIbα/vWF-mediated platelet function using a far more convenient procedure. Where the RIPA is most useful is in the evaluation of agglutination in the presence of low doses of ristocetin (≤ 0.5 mg/mL versus 1.0 and 1.5 mg/mL). A normal response is lack of agglutination using this reduced stimulation. Patients with vWF abnormalities that result in increased GPIbα binding aggregate platelets with low-dose ristocetin, which allows detection of type 2B disease. An important limitation that applies equally to all endogenous platelet assessment tests is that the test does not work properly in patients with thrombocytopenia. Because type 2B patients are susceptible to low platelet counts, they may need to wait for the thrombocytopenia to subside before the confirmatory RIPA test can be done.

Another potentially important application of the RIPA test described involves the distinction between whether the abnormality for hyperresponsive vWF-GPIbα binding lies in the vWF or the GPIb on the platelets, corresponding to type 2B vWD and platelet type vWD (PT-vWD), respectively.36,37 In this method, patient platelets and plasma are separated and tested together or in cross-mixture with control platelets or plasma. Patients with a platelet GPIbα defect show a normal negative response when their plasma is tested with control platelets and a persistently elevated response when their platelets are tested with normal plasma. The addition of high vWF concentrates such as cryoprecipitate also has been used, with the theory that overwhelming with normal vWF can overcome the low-dose ristocetin aggregation in type 2B. These tests are labor intensive and prone to artifact from the additional platelet manipulation and the ambiguities of platelet aggregation, but they may assist in pinpointing this diagnosis in patients with vWD.

von Willebrand Factor Propeptide

Measures of the vWF propeptide (ie, the D1-D2 portion of the immature vWF protein), have been demonstrated as having potential clinical use in the prediction of DDAVP responsiveness.38-40 Specifically, high ratios of pro-vWF to vWF:Ag are associated with reduced circulating survival of mature vWF, one of the general mechanisms postulated to be responsible for type 1 vWD. The theory is that the propeptide degradation and removal is independent of the mature vWF degradation and removal, so increased removal of antigen increases the relative propeptide amount. This interpretation is supported by the differing half-lives: 2 to 3 hours for vWFpp and 8 to 12 hours for mature vWF (probably longer in non–blood type O patients) and the relative constancy of vWFpp half-lives in patients with reduced vWF plasma survival. Patients with increased ratios are also associated with a series of particular vWF gene mutations affecting assembly. They are often classified initially as type 1 patients, but they may be best categorized as type 2A (IIE).

The vWF propeptide level measurement is based on selective immunologic detection in a standard ELISA. A limitation lies in that the anti-vWFpp antibody (known as Mango) is only available as a research use only reagent kit from GTI Diagnostics. Its general use in the routine subclassification of vWD remains to be fully demonstrated.

Flow Cytometry for von Willebrand Disease

Detection of platelet aggregation and detection of vWF binding to platelets with fluorescently labeled antibodies by flow cytometry has been proposed as an alternate or complementary method for vWD diagnosis and monitoring.41-43 There are some theoretical differences between results obtained by these methods and the corresponding functional and quantitative values obtained in the RCof/CB assays and the antigen levels. The platelet aggregation involves the use of patient platelet-rich plasma incubated with ristocetin, followed by particle size detection. More activation is reflected in the higher distribution of particle sizes, with more of the larger particles corresponding to activated platelet aggregates. In this regard, it is more analogous to the PFA-100 in that the patient’s own components are used, with the difference that the less discriminate platelet activator ristocetin is used. As would be expected, the quantitation of vWF seems to correlate well to the antigen detection by traditional methods. Putative advantages of flow methods are high sensitivity, small volumes, and speed of results. Although cost, standardization, and labor intensity may be argued to be comparable in theory, in practical terms, a clear advantage has not been demonstrated. This is particularly true in light of the rather extensive specimen preprocessing dilutions, count adjustments, and incubations used. The ability of these flow tests to detect abnormalities in multimer distribution has not been shown, which raises questions about the relative use of the methods as proposed. Results thus far merit further exploration, however.

Factor VIII and Factor VIII-vWFB

The measurement of coagulation factor VIII is routinely used in the evaluation of patients for vWD. Apart from being helpful in the identification of the relatively common hemophilia A, levels of factor VIII are usually low or low-normal in the different types of vWD and are low in the variant that results in low factor VIII binding (type 2N). The method of choice is based on the degree of correction of PTT in factor VIII–deficient plasma, which is standardized against international standards and reported as a percentage of normal or IU/dL. Antigen-based chromogenic assays are also available and produce satisfactory results.

In the specific vWD subtype 2N, its differentiation from hemophilia A can be made by using antibodies that detect the bound conformation of factor VIII with vWD. This factor VIII-vWF binding test demonstrates a disproportionately low level of binding to factor VIII, relative to the vWF antigen concentration in the vWD variant, whereas it is proportional to the vWF concentration in hemophilia.

Other Approaches: Correlation Spectroscopy

Alternative methods for the detection of vWF antigen concentration and multimer distribution are being pursued. One such method being studied by Torres and Levene44 involves the use of correlation spectroscopy. The principle is based on the relative differences in Brownian motion translational mobility of multimers of different sizes. Fluctuation analysis, including autocorrelation and photon counting, of fluorescently tagged antibody bound molecules in small volumes of their native plasma allows determination of differences in the concentration and distribution of vWF multimers between patients and controls and potentially reveals conformational changes and binding defects. It has the advantages of minimal preparation, rapid analysis, small volumes, and low expense. The preliminary data show potential for the eventual routine evaluation of vWF multimers in a variety of patients for diagnosis and monitoring of coagulation abnormalities, although further studies are needed and are currently in progress.

General Test Considerations

Freeze-thaw cycles cause variable degradation of multimers, resulting in uninterpretable results because of artifactually low antigen levels and RCof activity. Similarly, slow thawing methods can inadvertently cause cryoprecipitation with variable decreases in observed values. The recommendation for storage is that collection be followed by a quick spin for preparation of platelet-poor plasma, which should then be frozen separately in smaller aliquots. Samples should be thawed at 37°C for several minutes and used quickly thereafter, particularly for tests that are sensitive to high molecular weight multimers. Although low-resolution multimer analysis seems to remain relatively unaffected for gross abnormalities on refrozen and rethawed specimens, degradation can be detected within a few hours using sensitive techniques, even in the absence of high molarity urea or low ionic buffer (unpublished observations).

DIAGNOSTIC ISSUES

Blood Type, Race, Antigen Levels, and Type 1 Disease

A significant challenge in identifying people affected with vWD is the relationship between ABO blood type and vWF levels. Correlations have been established in large blood donor studies and subsequently confirmed by others. Table 1 shows data from four such analyses. The first often-quoted study is based on 1117 blood donors in Wisconsin.45 The second study is a pedigree analysis of families containing members with idiopathic thrombosis.46 The third study evaluated the blood group and vWF antigen level association with a history of thrombosis in patients presenting to a hemostasis clinic.47 The last evaluated the genetic polymorphism/mutation Y1584C in normal blood donors in the United Kingdom.48

Table 1.

Correlation of ABO blood type with vWF:Ag levels in four different studies

| Study 1 (Gill 1987) |

Study 2 (Souto 2000) |

Study 3 (Scheleef 2004) |

Study 4 (Davies 2007) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IEP |

ELISA |

Particle Immunoassay |

Particle Immunoassay |

|||

| Blood Donors (1117) |

Familial Idiopathic Thrombophilia (328) |

Controls (236) |

Thrombosis (355) |

Wild-Type Donors (5000) |

Y1584C Donors (100) |

|

| vWF:Ag (2 SD) (U/dL) |

vWF:Ag (% Normal) | vWF:Ag (IU/dL) |

vWF:Ag (IU/dL) |

vWF:Ag (IU/dL) |

vWF:Ag (IU/dL) |

|

| Type O | 75 (36–157) | 77 ± 27 | 103 ± 25 | 123 ± 42 | 95 ± 29 | 58 ± 14 |

| Type A | 106 (48–234) | 114 ± 40 | 117* | 161* | 124 ± 37 | 98 ± 34 |

| Type B | 117 (57–241) | 103 ± 30 | 140 ± 30* | 165 ± 30* | 131 ± 37 | 108 ± 38 |

| Type AB | 123 (64–238) | 137 ± 34 | 135 ± 20* | 180 ± 25* | 137 ± 43 | 119 ± 20 |

Method and corresponding units are described. Standard deviations are given where available. Values with asterisk (*) are estimates from graphical representation of data.

Several points are worth noting. First, it is evident that there is significant variation in normal levels as determined at different institutions. The use of different methods (and slightly different units) does not account for the variation observed given that method correlation studies and other published measured ranges have validated the relative consistency of the various techniques. The revaluation of the WHO IS calibration standard in 2001 may have had an influence on measures because it represents a 6% increase in reported antigen levels.24 Regardless, although surveys from various countries have shown acceptable interassay and interinstitution variation, this comparison demonstrates that a significant need remains for individual institutions to establish their own reference ranges based on their specific populations.

A consistent finding, however, is that a strong correlation exists between blood type and vWF:Ag levels: significantly lower vWF antigen levels are associated with type O blood, somewhere on the order of 25% to 30% lower than non–type O individuals. For vWD, it is relevant that normal blood type O donors have ranges that overlap significantly with antigen levels considered to be in the VWD range. Not shown here is that this correlation is heavily influenced by race. Non-white individuals have significantly higher vWF:Ag levels, so much so that even type O non-white persons have levels that approximate average normal levels and non–type O non-whites have the highest baseline vWF:Ag.49 These observations have prompted the suggestion that blood type- and even race-specific normal ranges be used.

As to the reason for the blood type and vWF:Ag correlation, recent evidence points to increased clearance in blood type O individuals as a potential mechanism of the observed trend.50 There is some indication that H-type carbohydrate antigenic determinants on vWF play a role in this clearance.51 This might explain the variation in blood type A, which has been shown to be influenced by the H antigen expression differences seen in blood types A1O versus A2O versus AA. A key consideration is that bleeding symptoms correlate better with overall vWF antigen levels than with levels relative to blood type-specific ranges. That is, blood type O individuals are generally at higher risk for excessive bleeding and, according to the third study mentioned earlier, are less likely to become hypercoagulable. It is also relevant that normal blood type and race-specific ranges would be challenging and costly to define for a given institution, with large patient number requirements. As a result, the recommendation is that blood typing not be used for the clinical purpose of evaluating coagulopathy and that vWF:Ag levels be considered an imperfect but direct measure of bleeding risk after site-specific validation of overall normal ranges. Importantly, the distribution sensitive activity assays seem to show a similar association by blood type,52 so ratios are not affected, which further obviates the need for blood type-specific reference ranges.

Study 4 from Table 1 shows that baseline vWF levels across blood types are also reduced with the presence of the Y1584C polymorphism but that donors with blood type O have the bulk of the disease-range antigen levels. Still, it seems that the primary determinant of bleeding risk in these patients remains the vWF antigen level, making this type of polymorphism determination unnecessary for clinical purposes.

Another relevant point for accurate assessment of risk is that vWF levels also vary in response to conditions such as pregnancy, inflammatory illness, hyperthyroidism, and exercise. In an interesting (if odd) demonstration of the sensitivity of vWF levels, subjects had levels increase three- to fourfold in response to an induced syncopal episode.53 Practically, values of vWF:Ag less than 50 IU/dL or 50% of normal pool, in the proper clinical setting, are suggestive. If vWF:RCof levels are also less than 50% with low antigen levels, suspicion should be higher. Antigen or activity levels less than 30 IU/dL (some advocate 20 IU/dL) increase specificity a great deal with relation to a true diagnosis of vWD, identifiable mutations, and more severe bleeding symptoms. In the end (see later discussion), studies still suggest that bleeding scores are better predictors of future bleeding episodes than vWF levels in isolation, particularly histories of postoperative bleeding. The PFA-100 closure times, when properly used, also could be useful in excluding a bleeding propensity. Repeat testing at a later date reduces the chance of misclassifying in light of confounding effects such as an acute phase reaction or illness.

A conceptual framework for interpreting vWF:Ag levels and mutations can be formed from this and similar studies (Fig. 4). It seems evident that overall vWF associated bleeding risk is the result of the complex compound effect of blood type–related natural vWF:Ag levels plus the combination of any mutations that may affect the synthesis, release, conformation, binding, degradation, or clearance of vWF. There are likely other unidentified mechanisms. Certainly, other coagulation components also modulate this risk. In short, we can reinforce the view that we need more data and better tools. In any case, the antigen and activity levels that are derived from the multimer distribution remain critically important parameters, even if the specific contribution to overall bleeding risk in individual cases cannot be defined fully.

Fig. 4.

Conceptual framework for vWF contribution to bleeding risk illustrates the dependence on multiple factors.

Bleeding Score and Diagnostic Approach

Although bleeding history is a natural part of assessing bleeding risk, it was only relatively recently that standardization in bleeding history for vWD assessment evolved. In 2006, a questionnaire published by the European Union multicenter group studying the Molecular and Clinical Markers for Diagnosis and Management of Type I Von Willebrand Disease (MCMDM-1 VWD) showed excellent discrimination between individuals at increased risk of bleeding with vWF abnormalities and unaffected individuals.54 It is derived from a more extensive bleeding score system that has the significant drawback of requiring approximately 40 minutes for completion. The newer abbreviated questionnaire is available at http://www.euvwd.group.shef.ac.uk/bleed_score.htm. This quicker, simplified approach includes questions on frequency and severity of excessive bleeding as the result of tooth extraction, surgery, oral cavity conditions, minor wounds, nosebleeds, menorrhagia, gastrointestinal problems, postpartum, hematomas in muscles, and hemarthroses and bleeding into the central nervous system. Points are added based on positive bleeding episodes ranging from no bleeding postsurgical or traumatic bleeding (−1) to need for blood transfusion or desmopressin therapy (+4). Total points range from −3 to 45, but a threshold of points (bleeding score 4) correlates with risk of vWD as determined by complete testing using vWD diagnostic guidelines that use traditional tests. The sensitivity using this threshold for identifying cases with abnormal vWF testing is reportedly near 100% and specificity is approximately 87%.55 By all measures, it serves well as an initial screen.

In using the bleeding score system, however, it should be noted that the validation was performed on patients who were almost exclusively over 15 years of age. Younger patients may present with a more limited personal history. In these cases, the family history may be more important and the physician faces more of a judgment call in terms of additional testing. In borderline cases, there is a risk of falsely labeling a patient with vWD, which leads to unnecessary cost and worry, possible delaying procedures, and potentiating what could turn out to be harmful prophylaxis.

Typically, if the evidence points to a true bleeding diathesis based on clinical history and family history, indicated tests are: complete blood count, including a platelet count, a PT and PTT, and a fibrinogen level (usually obtained concurrently with PTT). When the clinical evidence is strong that a bleeding disorder exists, the cadre of traditional vWD tests may be indicated from the start, namely vWF:Ag, vWF:RCof, and factor VIII. Otherwise, these tests would be reserved for when the initial tests do not show any abnormality that suggests a different reason for the bleeding tendency, such as thrombocytopenia or liver disease. An isolated prolonged PTT that corrects upon mixing 1:1 with normal plasma, both immediately and after 1- or 2-hour incubation times (excluding possibility of a factor inhibitor present), may be consistent with hemophilia A or vWD, so additional vWD testing is warranted. Many physicians use low-resolution multimeric testing as a complement to the vWD tests, mainly to evaluate the possibility of types 2A, 2B, or 3 disease. Intermediate resolution multimer analysis presents the previously described advantage of detecting more subtle abnormalities associated with variants of type 1 disease (such as type 2A[IIE] described later) and types 2M and 2N, but it is not readily commercially available. A similar scheme incorporates the use of the vWF:CB assay instead of the vWF:RCof assay, but in terms of standardized classification, there is much less experience with the vWF:CB assay, and neither has fully validated strict criteria in terms of functional to antigen ratios that can classify with high enough accuracy. The question of when to use PFA-100, particularly in screening, remains somewhat controversial, mainly because of the sensitivity and specificity issues.

In light of the diagnostic issues, standard criteria remain largely clinical and are based on the 2006 publication by the scientific and standardization committee of the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. A simplified diagnostic scheme is presented in Fig. 5. In general, it is useful to think of the bleeding history as being critical in the clinical evaluation of vWD. A high pretest probability improves significantly the ability of the tests to produce accurate results. Without it, results are prone to errors in diagnosis, classifying normal individuals with borderline levels of antigen as affected and missing affected at-risk patients who happen to have had a reactively high level at time of sampling.

Fig. 5.

General diagnostic scheme for vWD evaluation in a patient presenting with either personal or family history of bleeding or an abnormal coagulation test. Scheme is based on NHLBI guidelines79 and Favoloro.31

Molecular Testing

Many molecular techniques have been used in the identification of vWD mutations, but gene sequencing using site-specific primers remains the gold standard. Unfortunately, there are significant drawbacks and pitfalls. At 178 kb, the gene is much too long to make DNA sequencing economically viable as a diagnostic test, even using the most modern techniques available. Polymorphisms are abundant, with more than 130 reported to date, which adds some challenges to the design of a simplified molecular diagnostic approach. The presence of a pseudogene on chromosome 22 further complicates analysis by creating a source of potential interference during isolation and detection, although it is relevant to note that mutations in the pseudogene can be introduced into the fully encoded gene, resulting in clinically significant disease in offspring.56 Perhaps the greatest difficulties come from four properties of vWD mutations: (1) more than 200 mutations have been associated with vWD; (2) compound mutations occur with regularity; (3) many patients with vWD have normal vWF genes by sequencing; and (4) mutations and other factors contributing to vWD may be outside the vWF gene. A Web site at the University of Sheffield serves as repository of vWF mutations (http://www.vwf.group.shef.ac.uk/).

When molecular testing is performed (primarily for research studies), an approach is to sequence exons 1 and 18 to 52 using polymerase chain reaction amplification with site-specific primer sets. If no mutation is found, exons 2 to 18 are also sequenced. Alternatively, all the exons are sequenced. Unfortunately, exon sequencing misses many of the possible mutations that occur in the intervening regions, especially splice sites, and in the gene regulatory regions upstream from the protein encoding portion. Parenthetically, intron 40 has polymorphism and heterozygosity with potential for paternity and other forensic testing as reported recently.57 vWF gene properties make it difficult to come up with a cost-effective and efficient molecular diagnostic test strategy for vWD, however.

MECHANISTIC-AND GENOTYPIC-BASED CLASSIFICATION

With all these caveats, we can begin to undertake the task of identifying patterns in genotype/phenotype correlations to help us better predict clinical behavior. The current favored classification scheme as described follows a traditional designation of types 1, 2 and 3 corresponding to (1) type 1: decrease in overall multimers with normal ratio of activity (vWF:RCof or vWF:CB) to antigen; (2) type 2: qualitative deficiencies of vWF; and (3) type 3: Absence or near absence of vWF multimers.

A basic rationale for this classification exists in the use of a standard laboratory medicine designation of quantitative defects as type 1 and qualitative defects as type 2. Severity of bleeding symptoms generally increases as one goes from type 1 to type 3, and prevalence decreases from type 1 to type 3. Type 2 is subdivided into types 2A, 2B, 2N, and 2M on the basis of differing test results and multimer patterns with the associated etiologies. The old 1987 classification used further subcategorization of type 2A into subclasses IIA through IIE (with case reports for IIF through II-I), which many in the field continue to use. Causally, they seem to correspond to different identifiable mechanisms, but currently this distinction is not easily achieved. The research work that has evolved in the past few years has identified molecular mechanisms associated with genetic mutations in many of these subtypes, some of which were classified as type 1 using standard testing, which contributes to the confusion in vWD classification. An important result of the genotypic classification work being undertaken is that it can start to assign potential mechanistic causes for the more subdivided classification work summarized in the 1987 classification by Ruggieri. In the future, we may return to that more detailed scheme, particularly if we can reorganize it mechanistically and genotypically to create a more accurate picture of abnormalities in vWF.

Type 1 and Type Vincenza

Several mechanisms have been identified or postulated as being responsible for the various forms of vWD that result in what is currently classified as type 1, including (1) decreased synthesis, (2) decreased secretion, (3) increased clearance, and (4) increased cleavage. Most of the studies have focused on evaluating these mechanisms in patients who have identified mutations. A significant proportion of patients (approximately 30%–35% of patients with type 1), however, do not have identifiable mutations with standard gene sequencing techniques.58-60 As a result, the large cohort studies that have been published in the past few years tend to separate patients on the basis of (1) presence or absence of mutations and (2) normal or abnormal multimer patterns on intermediate- to high-resolution gel electrophoresis. One of these studies58 observed that bleeding symptoms as determined by bleeding scores correlate to these categories:

Type 1/Abnormal multimers/No mutations: rare/only slightly abnormal bleeding scores

Type 1/Normal multimers/0, 1, or >1 mutation: moderately elevated bleeding scores

Type 1/Abnormal multimers/1 mutation: high bleeding scores

Type 1/Abnormal multimers/ >1 mutation: highest bleeding scores

Conceptually at least, it seems that identifiable abnormalities on multimer distribution by intermediate- or high-resolution electrophoresis have the most bearing on the predictable risk for bleeding. The presence of detectable mutations is less relevant, but compound mutations can have a significant cumulative effect. From the clinical laboratory point of view, one may consider that intermediate- or high-resolution gel electrophoresis is superior in terms of bleeding risk assessment in vWD. There also seems to be a rare but distinct subset of patients with abnormal multimers who have only slightly increased risk of bleeding. This group could have non-vWF generelated reasons for the abnormal multimer distribution or result from intron abnormalities with normal residual capacity to respond appropriately to bleeding injury.

Increased Clearance

The bulk of the vWF gene mutations that have been associated with reduced survival of circulating vWF are located in the D3 region, including mutations such as C1130G, C1130F, C1130R, and W1144G. The D3 region is associated with multimerization, but its specific role in clearance has not been elucidated. D4 region defects also have been linked to shortened survival, namely S2179F. Some of these D3 and D4 defects are associated with decreased satellite band intensity. In many cases, there is a concomitant minimal decrease in large multimers, the basis for categorization as type 2A, subclass IIE. Absence or decrease of these satellite bands and the minimal large multimer decrease would not be detected in low-resolution gel electrophoresis, leading to a diagnosis of type 1 vWD. Patients with these mutations also have been shown to have increased ratio of vWF propeptide to mature antigen ratio. The mature vWF half-life in these patients has been measured to be roughly 3.5 hours, significantly shorter than the normal patient approximations of 8 to 12 hours40 (possibly even longer in persons with non-blood type O).50 These patients are reported to have a marked increase in vWF:Ag in response to DDAVP, which lends credence to the theory that their vWF synthesis is unaffected. The shortened half-life abnormality is usually reflected in DDAVP challenge tests. The many-fold increases in antigen level tend to require sample draws at 30 minutes to 1 hour after infusion, however.

A related mutation in the D3 region that results in increased clearance is R1250H, which carries the designation of vWD-Vincenza. The R1205H mutation of vWD Vincenza results in a pronounced increase in clearance of vWF multimers. Genetic penetrance is high and is associated with an especially severe bleeding diathesis for a “type 1” disorder. Some have classified Vincenza as a type 2M vWD variant, based partly on the decreased RIPA and the decreased Ag/RCof ratio (although normal on some studies) observed in this disorder. The subtleness of the multimer abnormalities in vWD Vincenza often leads to characterization as type 1 using routine testing. Although originally thought to also correspond to increased ultra-large vWF multimers, this observation is now believed to represent a second associated abnormality. In some studies, the R1205H has been linked to a M740I mutation, especially among those from the Vincenza region, but no specific phenotypic characteristic has been attributed to this genetic feature. Like the other rapid clearance mutations, there is a pronounced response to DDAVP followed by a markedly shortened vWF:Ag survival, and the propeptide ratio is elevated.

Based on the available data, the grouping of these abnormalities into an increased clearance category seems reasonable, particularly because there are distinct phenotypic characteristics with clinical implications. When suspected and possible, it may also warrant genetic analysis, although the main practical use at this time is in genetic counseling.

Other Mechanisms in Type 1

At least one other subgroup of type 1 patients as defined by current criteria likely deserves a special designation. A subset of type 1 patients seems to have a moderate to high risk of bleeding, normal or near normal multimer distribution, and lower responses to DDAVP. Some of these cases correspond to the originally identified group of patients with low platelet vWF (type I platelet low), which when combined with the low DDAVP response suggests a synthesis defect in megakaryocytes and endothelial cells. An example mechanism was described in a case that demonstrated a mutation in the D3 region that resulted in an abnormal monomer that can incorporate itself during the multimer assembly and prevent multimer transport out of the ER.61 These patients and other “severe” type 1 patients are not adequately managed with DDAVP and require factor concentrate infusions or platelet transfusions during bleeding episodes. They are also characterized by markedly low vWF:Ag levels but visible multimers on gel electrophoresis, which reinforces the view that antigen levels less than 20 or 30 IU/dL in type 1 disease increases the likelihood of detectable mutations and more significant disease. These cases also support the idea that risk in type 1 disease still needs to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Other type 1 vWD cases are not as easily characterized. Nearly every region in the vWF gene has been associated with type 1 vWD, despite the strong association between certain regions and specific vWD subtypes. We may speculate that some of these mutations result in mild structural abnormalities with subtle effects in any of the synthesis, secretion, and degradations steps of the vWF life-cycle, and that, in combination, they result in decreased steady state or decreased responsiveness to injury and a bleeding diathesis. The continuing long-term studies of type 1 patients in Europe, Canada, and the United States should help us focus on the variables with the highest impact, but other than antigen levels and the DDAVP challenge, there is insufficient information to currently allow for the routine standardized identification of the highest risk type 1 patients.

Type 2A

Type 2A vWD patients share characteristics such as decreased functional/antigen ratio, reduced response to DDAVP, abnormalities in the multimer pattern, and increased risk of bleeding. They are probably the most common type of non-type 1 vWD; however, like type 1, type 2A represents a heterogeneous group of disorders with several different underlying mechanisms62 (Table 2). Of type 2A cases, the sub-subtype originally designated as IIA is generally considered the most common. It is caused by dominant mutations in the A2 domain (or the adjacent N terminal portion of the A3 domain) that create folding instability of the mature vWF protein such that mechanical unfolding is not needed to expose the nearby ADAMTS-13 cleaving site. As a result, increased proteolysis manifests on gel electrophoresis as a decrease in large multimers and increase in the proportion of the intermediate degradation products seen as satellite bands (see Fig. 3). The severity of the abnormality and resulting bleeding phenotype depends on the specific amino acid substitution because different degrees of instability can modulate susceptibility to cleaving and the ability to sustain large multimer assembly. Although there is insufficient evidence to fully support using the specific multimer pattern as a prognostic indicator in these cases, it seems logical that the proportional reduction in large multimers corresponds to the degree to which the mutation in a specific case is hampering normal clotting function.

Table 2.

Evolution of vWD classification scheme with distinguishing features and representative mechanisms and mutations

| 2006 | 1994 | 1987 | Multimers on Gel |

DDAVP Response |

Rcof:Ag Ratio |

Inheritance | Mechanism | Bleeding Risk | Representative Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | IA, I Platelet normal, l–2 | All present but↓ | Good | Normal | Autosomal dominant | Mild to moderate | Upstream regulatory region, D1,D2,D′/D3,A1,A2,A3,D4, B2,B3,C1,C2,CK | |

| l–3 | All present | Good | Normal | Autosomal dominant | Normal plasma vWF-Ag, low in platelets | ||||

| I Platelet low, I-1 | All present but↓ | Poor | Normal | Autosomal dominant | Impaired intracell transport, heterodimers | D′/D3-C1149R | |||

| 1 | 2M | Unclassified, I Vincenza | Large↑ (Variable)/large mildly↓ with satellite ↓(C1130) | Pronounced immediate but shortened half-life | Usually low (normal on some studies) | Autosomal dominant | Increased clearance, ↓RIPA | Moderate | D′/D3-R1205H or C1130F/G/R, W1144G |

| 2A | 2A | IB, I Platelet discordant | Large, mildly↓ | Poor–variable | Low | Autosomal dominant | Same as severe type 2M? | A1-R1374C/H? | |

| IIA (IIA-1, IIA-2, IIA-3) | Large and intermediate↓/satellite bands↑↑ | Poor–variable | Low | Autosomal dominant | Increased ADAMTS13 susceptibility | Mild to moderate | A2/A3 - C1272S, G1505R, S1506L, M1528V, R1569dl, R1597W, V1607DM G1609R, I1628T, G1629E, G1631D, E1638K, P1648S | ||

| IIC | Larger↓↓/satellite↓↓ | Poor | Low | Recessive–rare | Propeptide mutations impair Golgi multimer assembly and make resistant to ADAMTS13 | D2 | |||

| IID | Larger↓↓/abnormal satellite ↓↓/old numbered multimers | Poor | Low | Autosomal dominant–rare | Impaired dimerization in ER → Monomers become chain terminators | Hetero, moderate; homozyogous, severe | CK-C2010R | ||

| IIE | Larger↓/satellite↓ (Smeary) | Poor | Low | Autosomal dominant–rare | Impaired assembly at disulfide bonds | Mild to moderate | D3-Y1146C, C1153Y, T1107C | ||

| IIF, IIG, IIH, II-I | Larger↓/satellite ↓ abnormalities | Poor | Low | Rare | Case reports | ||||

| 2B | 2B | IIB | Large ± intermediate/satellite bands↑↑ | Contraindicated but increase in response | Often low (Ag normal, borderline RCof) | Autosomal dominant | ↑GPIb binding leads to platelet aggregation and clearance = ↑RIPA, periodic ↓plts | Variable, correlates with thrombocytopenia | A1/A2-C1272G/R, M1304Insm, R1306W/Q/L, I1309V, S1310F, W1313C, V1314F/L/P, V1316M, H1268D, P1337L, R1306W, R1341Q/W/L, R1308C/P, L1460V, A1461V |

| I New York, Malmö | Near normal | Good | Usually normal | Autosomal dominant | Increased RIPA but apparently normal function in vivo | Low to none - usually no thrombocytopenia | A1-P1266L/Q, R1308L | ||

| 2M | 2M | Type B | All present but↓ | Poor–variable | Low | Autosomal dominant | Impaired binding to GPIb | Variable-R1374C/H more severe | A1-Y1321D, G1324A/S, E1359K, K1362T, F1369I, R1374C/H, R1394I, K148deI, I1425F, I1526T |

| IC | Smaller/Satellite bands↓ | Hetero–good | Normal | Recessive | Decreased proteolysis | Heter, mild; homozygous, severe | B2-C2362F | ||

| ID | All↓/satellite bands↓ | Good | Low | Autosomal dominant? | Decreased RIPAMay be a Vincenza analog | ||||

| 2N | 2N | Normandy | Normal | Not indicated | Normal | Recessive | Impaired binding to factor VIII cause increased FVIII degradation | Severity depends on mutation. Mimicks mild hemophilia A | D′/D3-R854G=milder disease. Others include P812, R816W, R854Q, R1035 |

| 3 | 3 | III | Absent or nearly absent | None | Unmeasurable | Recessive | High | Nonsense, frameshift, deletions, unique | |

| Differences | Mutation Locus | Type 1 Criteria | |||||||

| 1994 | Only vWF gene | Decreased vWF:Ag but no multimer abnormalities | |||||||

| 2006 | Not restricted | Decreased vWF:Ag normal multimer distribution, may have satellite band abnormalities, normal activity-to-antigen ratio | |||||||

Data are compiled from multiple references as listed in the text.

Several other rarer type 2A subtypes have mechanisms that have been at least partially elucidated and generate distinct multimer patterns that are readily recognizable. The originally designated type IIC results from mutations in the D2 propeptide region that impair its ability to promote multimer assembly in the golgi, resulting in abnormally small multimers that adopt conformations resistant to ADAMTS-13–mediated proteolysis. Multimer profiles include only the smallest multimers and are devoid of satellite bands, yielding a characteristically clean gel pattern (see Fig. 3). Although sometimes touted as representative of type 2 disease on gel electrophoresis, only homozygous mutations result in the clearly identifiable phenotype, which makes this abnormality uncommon and somewhat unique.

Subtype IIE in the older classifications is another uncommon but distinct 2A subtype that may be labeled as type 1 based on low-resolution multimer analysis. In the variant that is currently classifiable as type 2A, the abnormality stems from mutations in the D3 domain that impair disulfide bond formation necessary for normal multimer assembly. Some decrease in the largest multimers reflects this impaired assembly, but the impairment is too subtle to be detected with most gels. The vWF:Rcof/vWF:Ag ratio may be near the normal range, but the more sensitive vWF:CB seems to be more clearly abnormal in these cases. Intermediate- and high-resolution gels also identify the reduced satellite band intensity, the cause of which remains unknown but which is possibly related to increased clearance, as seen with other D3 mutations that result in Vincenza-like phenotypes. The two may represent varying degrees of impairment of the same processes based on the specifics of the conformational abnormalities.