Dear Editors:

We read with interest the articles by Xiao et al1 and Du et al2 regarding severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS Co-V 2) shedding in feces, staining of viral nucleocapsid protein in the cytoplasm of gastrointestinal epithelial cells, and the characterization of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors across tissues in the human body. The relationship between coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), intestinal ACE2 expression, and gastrointestinal symptoms is worth exploring further, and may offer unique clues to the pathogenesis of intestinal inflammation.

We have previously characterized multiple components of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) in the terminal ileum and colon in patients with and without inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).3 Notably, all of the components of the classical and alternative RAS were expressed in the mucosa, demonstrating the presence of a locally active intestinal RAS. In particular, ACE2 was localized by immunohistochemistry to the brush border and epithelium, and ACE2 messenger RNA expression was 10-fold higher, and ACE2 activity 7- to 10-fold higher, in terminal ileal biopsies when compared to colonic biopsies in patients without IBD.3 ACE2 activity was lower in inflamed colonic biopsies than noninflamed biopsies from patients with IBD, and angiotensin (Ang) 1–7 immunohistochemical staining intensity was lower in colonic biopsies from patients with IBD when compared with healthy controls. Ang 1–7 has been shown to exert anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic, and antiproliferative actions in various tissues, and decreased myofibroblast proliferation and collagen secretion in cultured colonic myofibroblasts.3 ACE2 knockout mice had increased susceptibility to colitis and an altered microbiota profile, which was associated with higher colonic Ang II levels, the putative peptide of the classical RAS pathway that exerts proinflammatory and profibrotic effects.4 Plasma ACE2 activity was higher in patients with IBD, especially Crohn’s disease, than non-IBD controls, perhaps representing a compensatory mechanism.5

Intestinal ACE2 is also required for absorption of tryptophan, an essential amino acid required for niacin production. Pellagra, caused by the deficiency of niacin (vitamin B3), is characterized by intestinal inflammation and protein malnutrition.4 Serum tryptophan levels were lower in patients with IBD, especially Crohn’s disease, than controls without IBD.6

SARS-CoV-2, which, like the original SARS-CoV of earlier this century, infects humans via its spike proteins binding to ACE2 on mucosal membranes.7 Multiple mucosal surfaces express ACE2, including alveoli, esophagus, stomach, small bowel, and colon. The original transmission of COVID-19 from an animal reservoir to human, initially described in Wuhan, China, likely occurred by the oral route, perhaps mediated via intestinal ACE2.1 , 7 SARS-CoV was shown to induce shedding of the ACE2 ectodomain following cellular entry, dependent on tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α converting enzyme production.8 This was also associated with increased TNF-α production and tissue damage.8

Conceivably, if SARS-CoV2 also induces reduction of mucosal ACE2 after entry, intestinal inflammation may result via multiple mechanisms: elevated Ang II, reduced Ang 1–7 levels, increased TNF-α, and tryptophan deficiency. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, occur in approximately 4%–20% of patients with COVID-19, and severe colitis has recently been described. Hence, multiple potential targets for therapy for COVID-19, and intestinal inflammation in IBD, may result from further investigation of these pathways.

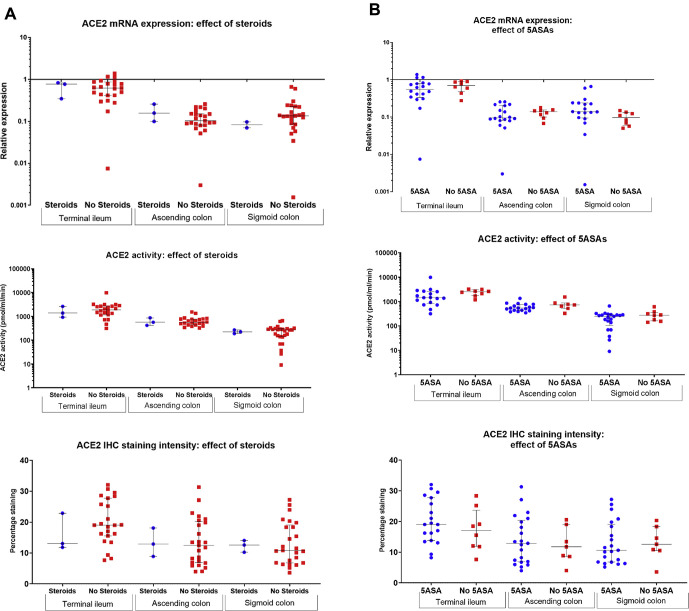

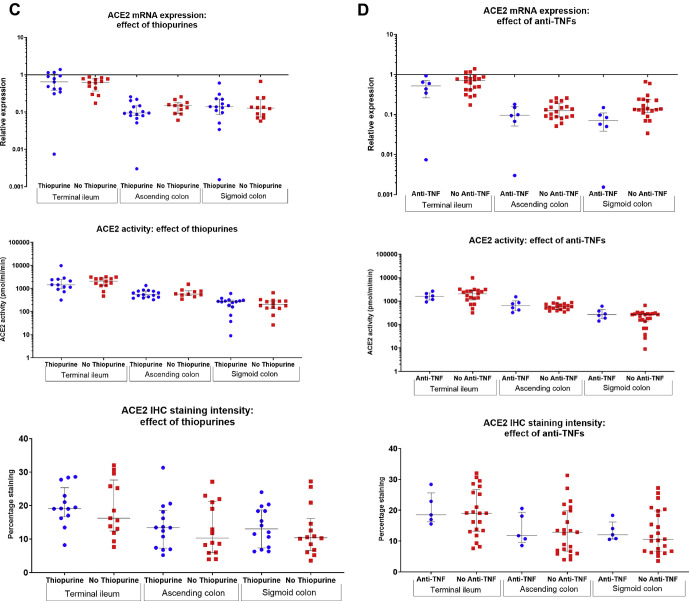

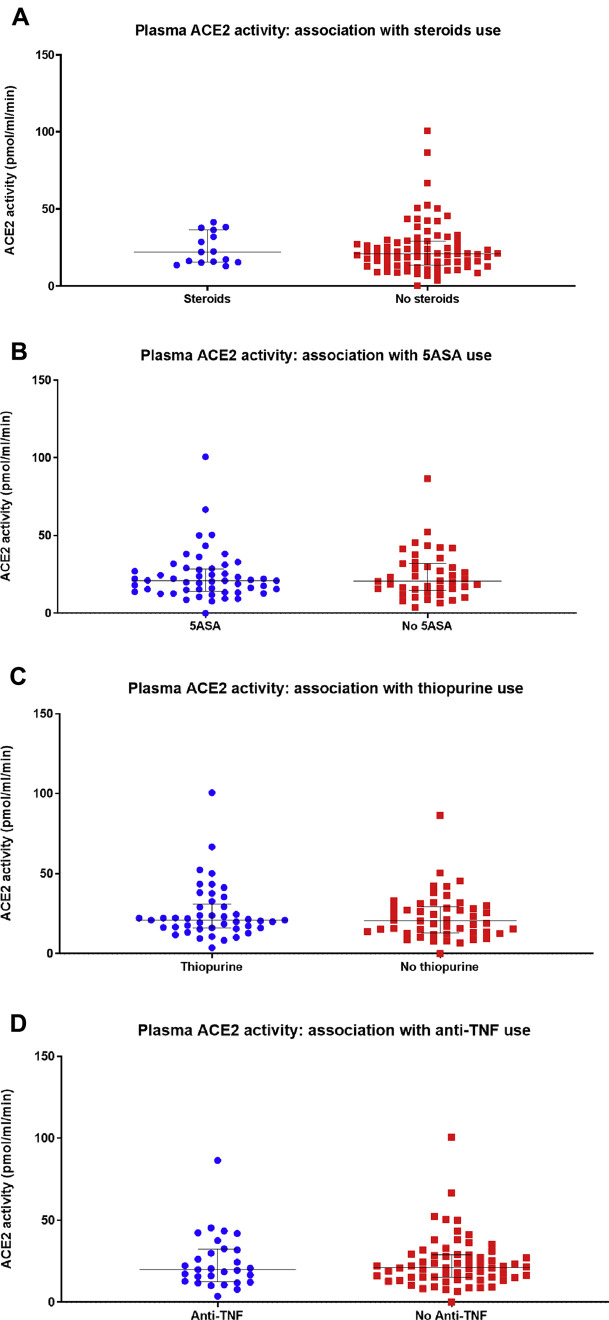

In our studies, we have additionally analyzed whether conventional therapies for IBD were associated with altered intestinal mucosal ACE2 expression. No association between steroids, mesalamine, thiopurines, or anti–TNF-α medication use and terminal ileal or colonic ACE2 messenger RNA expression, ACE2 activity, or ACE2 immunohistochemical staining intensity was noted (Supplementary Figure 1). Furthermore, no effect of these drugs on plasma ACE2 activity was noted (Supplementary Figure 2). Whether the use of these drugs alters the risk of acquiring COVID-19, or developing gastrointestinal symptoms or other complications, remains to be elicited, as data are acquired in an international registry.

Supplementary Figure 1.

Association between (A) steroids, (B) mesalamines (5-ASA), (C) thiopurines, and (D) anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α agents and mucosal ACE2 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) activity, and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining intensity in colonoscopic biopsies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). No statistically significant differences were noted.

Supplementary Figure 2.

Association between (A) steroids, (B) mesalamines (5-ASA), (C) thiopurines, and (D) anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α agents and plasma angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). No statistically significant differences were noted.

Nonetheless, our understanding of IBD and intestinal inflammation may increase significantly after further investigation into ACE2 and its effects, potentially leading to new treatments for these conditions, and providing us with opportunities in the context of this tragic global pandemic.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.051.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Xiao F. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831–1833. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du M. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:2298–2301. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garg M. Gut. 2019;69:841–851. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashimoto T. Nature. 2012;487:477–481. doi: 10.1038/nature11228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garg M. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2015;16:559–569. doi: 10.1177/1470320314521086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nikolaus S. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:1504–1516. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang H. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:486–590. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haga S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7809–7814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711241105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]