Abstract

The emerging global infectious COVID-19 disease by novel Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) presents critical threats to global public health and the economy since it was identified in late December 2019 in China. The virus has gone through various pathways of evolution. To understand the evolution and transmission of SARS-CoV-2, genotyping of virus isolates is of great importance. This study presents an accurate method for effectively genotyping SARS-CoV-2 viruses using complete genomes. The method employs the multiple sequence alignments of the genome isolates with the SARS-CoV-2 reference genome. The single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotypes are then measured by Jaccard distances to track the relationship of virus isolates. The genotyping analysis of SARS-CoV-2 isolates from the globe reveals that specific multiple mutations are the predominated mutation type during the current epidemic. The proposed method serves an effective tool for monitoring and tracking the epidemic of pathogenic viruses in their global and local genetic variations. The genotyping analysis shows that the genes encoding the S proteins and RNA polymerase, RNA primase, and nucleoprotein, undergo frequent mutations. These mutations are critical for vaccine development in disease control.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, 2019-nCoV, Genotyping, Single-nucleotide polymorphism, COVID-19

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; DMV, double-membrane vesicle; ACE2, angiotensin converting enzyme 2; GATK, the genome analysis toolkit; MSA, multiple sequence alignment; NGS, next generation sequencing; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphisms; WHO, the world health organization

Highlights

-

•

This study genotyped 558 SARS-CoV-2 isolates from the globe as of March 23, 2020.

-

•

Frequent mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 genome are in the genes of S protein, RNA polymerase, RNA primase, and nucleoprotein.

-

•

This study established a method for monitoring and tracing SARS-CoV-2 mutations.

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus in humans, first discovered in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, was initially named as 2019-nCoV and then designated as SARS-CoV-2 due to its taxonomic and genomic relationships with the species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus [1]. The present outbreak of the coronavirus-associated acute respiratory disease is named coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) by WHO. Since the pandemic of COVID-19, more than 332, 930 people from 147 countries and territories have been confirmed sicked and more than 14, 510 have died from the rapidly-spreading SARS-CoV-2 virus as of March 23, 2020 [2].

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are a family of enveloped positive-strand RNA viruses infecting vertebrates, named for the crown-like spikes on their surface. Coronaviruses belong to the familyCoronaviridae and the order Nidovirales. Coronaviruses can widely spread in humans, other mammals, and birds, and cause diseases such as the respiratory, intestinal, liver, and nervous systems. Human coronaviruses (HCoVs) were first identified in the mid-1960s. Seven common HCovs are CoV-229E (alpha coronavirus), CoV-NL63 (alpha coronavirus), CoV-OC43 (beta coronavirus), CoV-HKU1 (beta coronavirus), Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and current SARS-CoV-2. CoV-229E and CoV-OC43 are the cause of the common cold in adults during the mid-1960s. Disease manifestations associated with CoV-HKU1 and CoV-NL63 include the common cold and chronic pneumonia. Coronavirus-HKU1 has been predominantly reported in children in the United States but less common among adults. Three highly pathogenic coronaviruses, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2, which emerged in 2002, 2012, and 2019, respectively, have caused severe respiratory disease and thousands of deaths worldwide [3].

SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus harbors a linear single-stranded positive RNA genome. The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 genome consists of a leader sequence, ORF1ab that encodes proteins for RNA replication, and genes for non-structural proteins (nsp) and structural proteins. The genomic leader sequence of about 265 bp is the unique characteristic in coronavirus replication and plays critical roles in the gene expression of coronavirus during its discontinuous sub-genomic replication [4]. ORF1ab encodes replicase polyproteins required for viral RNA replication and transcription [5]. Expression of the C-proximal portion of ORF1ab requires (−1) ribosomal frame-shifting. The first non-structural protein (nsp) encoded by ORF1ab is Papain-like proteinase (PL proteinase, nps3). Nsp3 is an essential and the largest component of the replication and transcription complex. The PL proteinase cleaves non-structural proteins 1–3 and blocks the host's innate immune response, promoting cytokine expression [6,7]. Nsp4 encoded in ORF1ab is responsible for forming double-membrane vesicle (DMV). The other non-structural proteins are 3CLPro protease (3-chymotrypsin-like proteinase, 3CLpro) and nsp6. 3CLPro protease is essential for RNA replication. The 3CLPro proteinase is accountable for processing the C-terminus of nsp4 through nsp16 in all coronaviruses [8]. Therefore, conserved structure and catalytic sites of 3CLpro may serve as attractive targets for antiviral drugs [9,10]. Together, nsp3, nsp4, and nsp6 can induce DMV [11].

SARS-coronavirus RNA replication is unique, involving two RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RNA pol). The first RNA polymerase is a primer-dependent non-structural protein 12 (nsp12), and the second RNA polymerase is nsp8. In contrast to nsp12, nsp8 has the primase capacity for de novo replication initiation without primers [12]. Nsp7 and nsp8 are important in the replication and transcription of SARS-CoV-2. The SARS-coronavirus nsp7-nsp8 complex is a multimeric RNA polymerase for both de novo initiation and primer extension [12,13]. Nsp8 also interacts with ORF6 accessory protein. The nsp9 replicase protein of SARS-coronavirus binds RNA and interacts with nsp8 for its functions [14].

Furthermore, the SARS-CoV-2 genome encodes four structural proteins. The structural proteins possess much higher immunogenicity for T cell responses than the non-structural proteins [15]. The structural proteins are involved in various viral processes, including virus particle formation. The structural proteins include spike (S), envelope (E), membrane protein (M), and nucleoprotein (N), which are common to all coronaviruses [16,17]. The spike S protein is a glycoprotein, which has two domains S1 and S2. Spike protein S1 attaches the virion to the cell membrane by interacting with host receptor ACE2, initiating the infection [18,19]. After the internalization of the virus into the endosomes of the host cells, the S glycoprotein is induced by conformation changes. The S protein is then cleaved by cathepsin CTSL, and the unmasks the fusion peptide of S2, therefore, activating membranes fusion within endosomes. The spike protein domain S2 mediates fusion of the virion and cellular membranes by acting as a class I viral fusion protein. Specially, the spike glycoprotein of coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 contains a furin-like cleavage site [20]. The furin recognition site is important for being recognized by pyrolysis and therefore, contributing to the zoonotic infection of the virus. The envelope (E) protein interacts with membrane protein M in the budding compartment of the host cell. The M protein holds dominant cellular immunogenicity [21]. Nucleoprotein (ORF9a) packages the positive-strand viral RNA genome into a helical ribonucleocapsid (RNP) during virion assembly through its interactions with the viral genome and a membrane protein M [22]. Nucleoprotein plays an important role in enhancing the efficiency of subgenomic viral RNA transcription as well as viral replication.

The increasing epidemiological and clinical evidence implicates that the SARS-CoV-2 has a stronger transmissibility than SARS-CoV and lower pathogenicity [23]. However, the mechanism of high transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is unclear. DNA sequence comparisons using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are often used for evolutionary studies and can be especially beneficial in recognizing the mutated coronavirus genomes, where high mutations can occur due to an error-prone RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in genome replication [24,25].

To understand the virus evolution of SARS-CoV-2 from the genome mutation context, this study establishes the SNP genotyping method and investigate the genotype changes during the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The results show that the genotypes of the virus are not uniformly distributed among the complete genomes of SARS-CoV-2. This genotyping study discovers a few highly frequent mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 genomes. The highly frequent SNP mutations might be associated with the changes in transmissibility and virulence of the virus. The mutations are located in the S protein, RNA polymerase, RNA primase, and nucleoprotein, which are fundamental proteins for vaccine efficacy. Therefore, the high-frequency SNP mutations are important factors when developing vaccines for preventing the infection of SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus.

2. Methods and algorithms

2.1. Multiple sequence alignments (MSA)

Total 558 complete genome sequences of the SARS-CoV-2 strains from the infected individuals are retrieved from the GISAID database [26] as of March 23, 2020. Only the complete genomes of high-coverage and having no stretches of’NNNNN’ are included in the dataset. The countries and territories, which are infected by SARS-CoV-2 and share the complete genomes of SARS-COV-2, are Australia (AU), Belgium (BE), Brazil (BR), Canada (CA), Chile (CL), China (CN), Czech Republic (CZ), Denmark (DK), England (UK), Finland (FI), France (FR), Georgia (GE), Germany (DE), Hong Kong (HK), Hungary (HU), India (IN), Ireland (IE), Italy (IT), Japan (JP), Korea (KR), Kuwait (KW), Mexico (MX), Netherlands (NL), New Zealand (NZ), Scotland (UK), Singapore (SG), Switzerland CH), Sweden(SE), Taiwan (TW), Thailand (TH), United Kingdom (UK), Unites States (US), and Vietnam (VN).

The complete genome sequences are aligned with the reference genome of SARS-CoV-2 by MSA tool Clustal Omega using the default parameters [27]. The aligned genomes are then re-positioned according to the reference SARS-CoV-2 genome (GenBank access number: NC_045512.2) [28]. The structural variants of deletion and insertions that form gaps in MSA are considered when mapping the SNPs onto the reference genome. Because of the limitation in sequencing technology, the individual virus genomes are not usually complete, the sequences at two ends are missing or uncertain, the length of the virus genomes are not the same as the reference genome. Therefore, the SNPs are positioned on the reference genome.

2.2. SNP genotyping

The SNP mutations, including nucleotide changes and the corresponding positions in a genome, are called an SNP profile. The SNP profiles of SARS-CoV-2 isolates are retrieved and parsed from the aligned genomes according to the reference genome SARS-CoV-2. The SNP profile of the complete genome of a virus can be considered as the genotype of the virus.

2.3. Jaccard distance of the SNP variants

The Jaccard similarity coefficient J(A, B) of two sets A and B is defined as the intersection size of the two sets divided by the union size of two sets (Eq. (1)) [29].

| (1) |

The Jaccard distance is a metric on the collection of finite sets. The Jaccard distance d J(A, B) of two sets A and B is scored as the difference between 100% and the Jaccard similarity coefficient (Eq. (2)).

| (2) |

The genetic relationship of two virus isolates, which are represented by the SNP sets A and B within the two virus genomes, respectively, can be inferred by the Jaccard distance of the SNP sets A and B. The Jaccard distance of SNP variants was adopted in the phylogenetic analysis of human or bacterial genomes [[30], [31], [32]]. In this study, we use the Jaccard distance of the SNP mutations of SARS-CoV-2 genomes to measure the dissimilarity of virus isolates.

2.4. Transmission analysis of virus isolates by SNP genotyping

Because a mutation is rarely reversed, more SNPs in a virus occur along time. Let A and B represent two SNP sets of the virus, if A is the proper subset of B, i.e., (A ∈ B, A ≠ B), then B can be considered as one of A's descendants A, and A can be considered as the ancestor of B. To this end, we propose the directed Jaccard distance D J(A, B) of two SNP sets A and B as the measure of mutual relationship (Eq. (3)). Obviously, if B is a descendant of A, then D J(A, B) is positive; otherwise, if A is a descendant of B, D J(A, B) is negative. In all the descendants of an SNP A, the closest descendant is the one having the minimum D J(A, B) of the A descendant sets.

| (3) |

For two SNP sets A and B, if and , then the two viruses are relatives, sharing common SNP mutations. If two SNP sets are neither descendant-ancestor nor relatives, the corresponding two viruses are isolated mutants. Hence, the relevance of virus isolates can be identified from the directed Jaccard measure on the SNP genotypes.

Though the source of SARS-CoV-2 varies, we still consider the virus samples were randomly collected for sequencing. If a virus strain among all sequenced viruses has many descendants in the genome set, this strain is conferred with high transmissibility. Therefore, the SNP mutations in this strain are critical for increased transmissibility.

The directed Jaccard distances of the SNP mutations are used to identify the relationships of virus strains, therefore, the genotyping method may determine the virus transmission pattern. The pipeline for SNP genotyping and analysis is described in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1

SNP genotyping analysis of SARS-CoV-2.

Input: The complete genomes of SARS-CoV-2 strains.

Output: SNP genotypes of SARS-CoV-2 strains.

Step:

- 1.

Divide the complete genomes of SARS-CoV-2 strains into subsets based on their originating territories.

- 2.

Add the reference genome of SARS-CoV-2 to each subset of the complete genomes.

- 3.

Perform multiple sequence alignments for each subset genomes using Clustal Omega.

- 4.

Convert the alignment files to SNP profiles using the reference genome of SARS-CoV-2.

- 5.

Merge the SNP profiles of all virus genomes.

- 6.

Calculate the pairwise directed Jaccard distances of all the SNPs profiles.

- 7.

Analyze the descendants, ancestors, and relative relationships of each SNP genotype from the Jaccard distances.

2.5. Data and computer programs

The genomic analytics is performed using computer programs in Python and Biopython libraries [33]. The GISAID Ids of SARS-CoV-2 isolates are listed in the supplementary material. The SNP profiles of SARS-CoV-2 are available upon request.

3. Results

3.1. Genotyping SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus isolates from the globe

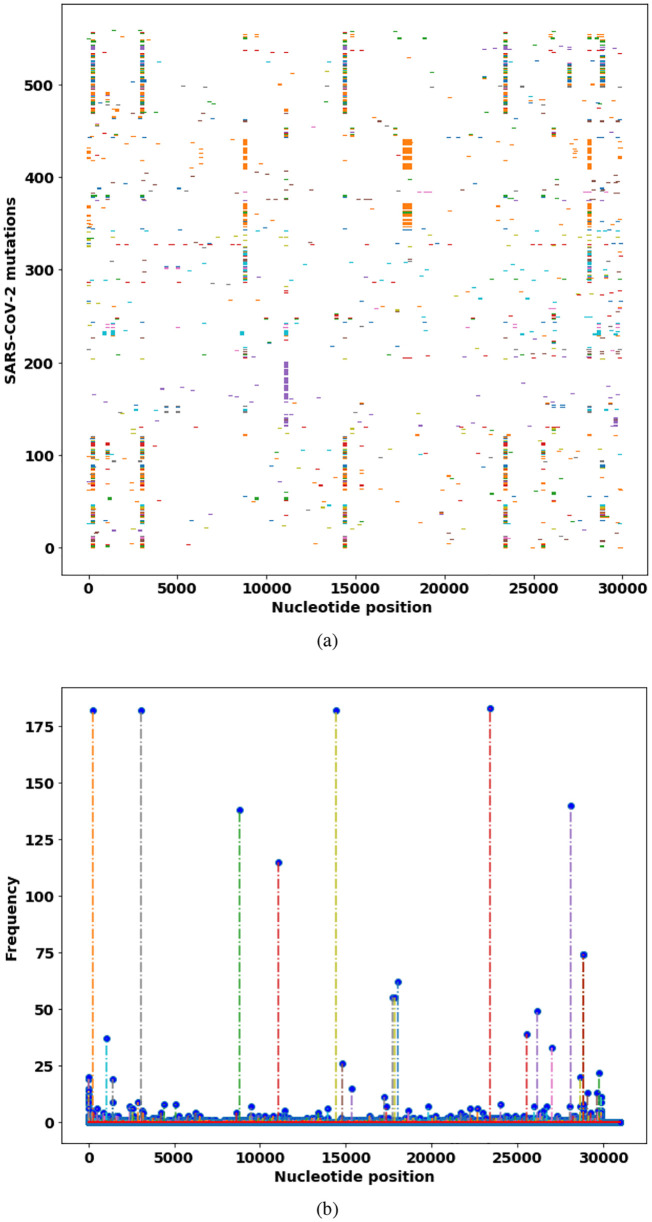

This study retrieved the SNP genotypes of 558 SARS-CoV-2 strains in GISAID database from the globe. To investigate the SNP distributions among all the virus isolates, the SNP profiles of all the virus isolates from the globe are visualized and compared for the frequency of each SNP mutation in the virus sets. The results show large mutation diversity in these virus isolates (Fig. 1 , Table 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of SNP mutations of SARS-CoV-2 isolates from the globe. (a) The SNP profiles of mutations in 442 SARS-CoV-2 isolates. (b) Frequencies of the single SNP mutations on the genome. The nucleotide positions are on the reference genome of SARS-CoV-2.

Table 1.

High-frequency single SNP genotypes in SARS-CoV-2.

| SNP mutation | protein mutation | frequency |

|---|---|---|

| 241C > T | leader sequence | 178 |

| 3037C > T | synonymous mutation (nsp3, F105F) | 182 |

| 8782C > T | synonymous mutation (nsp4, S75S) | 138 |

| 11083G > T | nsp6, L37F | 115 |

| 14408C > T | RNA pol (nsp12, P323L) | 182 |

| 17747C > T | helicase, P504L | 55 |

| 17858A > G | helicase, Y541C | 55 |

| 18060C > T | synonymous mutation (3′-to-5’exonuclease, L6L) | 62 |

| 23403A > G | spike glycoprotein (S protein), D614G | 183 |

| 26144G > T | ORF3a, G251V | 49 |

| 27046C > T | membrane glycoprotein, T175M | 33 |

| 28,144 T > C | RNA primase (nsp8, L84S) | 140 |

| 28881G > A | nucleocapsid phosphoprotein (R203K) | 74 |

| 28882G > A | nucleocapsid phosphoprotein (R202R) | 74 |

| 28883G > C | nucleocapsid phosphoprotein (G204R) | 74 |

Note: The SNP mutation positions are on the reference genome. Nucleotide T represents nucleotide U in SARS-CoV-2 RNA virus genome. The frequencies of mutations are computed from 558 SARS-CoV-2 strains.

In the mutation frequency analysis, the mutations are due to the fact that RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) of RNA viruses lacks proofreading. However, the mutations are not equally distributed. The SNP mutations can be a single mutation and multiple mutations at a few fixed positions. The impacts and roles that these SNP mutations have on the pathogenicity and transmission ability of SARS-CoV remain to be determined by biochemical experiments. These divers mutations might impact both transmissibility and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2.

The first common SNP mutation in the SARS-CoV-2 genome is in the leader sequence (241C > T), an important genomic site for discontinuous sub-genomic replication. The leader sequence mutation 241C > T is co-evolved with three important mutations, 3037C > T, 14408C > T, and 23403A > G, which result in amino acid mutations in nsp3 (synonymous mutation), RNA primase (P323L), and spike glycoprotein (S protein, D614G), respectively. These three co-mutations (241C > T, 14408C > T, and 23403A > G) are in critical proteins for RNA replication (241C > T, 14408C > T) and the S protein (23403A > G) for binding to ACE2 receptor. We observe that these four co-mutations are prevalent in the virus isolates from Europe, where infections COVID-19 by SARS-CoV-2 are generally more severe than other geographical regions. Combined, these four co-mutations probably can confer increased transmissibility of the virus.

SARS-coronavirus RNA replication is unique, involving two RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRp). The first RNA polymerase is a primer-dependent non-structural protein 12 (nsp12), whereas the second RNA polymerase is nsp8. Nsp8 has the primase capacity for de novo initiation RNA replication without primers [12]. The most abundant SNP mutation in SARS-CoV-2 isolates is (28,144 T > C) in nsp8 protein, in which amino acid leucine (L) is mutated to serine (S). Our result is consistent with a previous study on 103 SARS-CoV-2 genomes in which SARS-CoV-2 virus is classified as S and L types by the two co-mutations (8782C > T and 28,144 T > C) [34].

The third abundant SNP mutation is (26144G > T) in nonstructural protein 3 (nsp3: G251V). The protein nsp3 works with nsp4 and nsp6 to induce double-membrane vesicles (DMV), membrane complex that acts as a platform for RNA replication and assembly [11].

The most significant SNP mutation (23403A > G) is located in the gene encoding spike glycoprotein (S protein: D614G). The S protein in the SARS-CoV-2 virus is an important determinant of the host range and pathogenicity. The S protein attaches the virion to the cell membrane by binding the host ACE2 receptor [35]. The mutation D614G is located in the putative S1–S2 junction region near the furin recognition site (R667) for the cleavage of S protein when the viron enters or exists cells [36]. However, the actual functional impact of this high-frequency SNP mutation (23403A > G) in the S protein (D614G) is unclear. The affinity strength of the mutation S protein (D614G) with the ACE2 receptor shall be further determined by biochemical experiments.

Especially, the SNP analytics result also shows that the primer independent RNA primase (nsp8) contains more mutations than any other proteins (28,144 T > C, 28881G > A, 28882G > A, and 28883G > C). The RNA polymerase and primase mutations may confer resistance to mutagenic nucleotide analogs via increased fidelity. The previous study indicated that a single mutation in RNA polymerase can improve the replication fidelity in RNA virus [37]. If a mutation is lethal or reduces the transmission ability, the mutations may not be carried on or get deceased. The SNP profiles demonstrate that the mutations in the envelope glycoprotein and RNA polymerases predominate. Only these mutations in the S protein that have strongly binding capacity to cell ACE2 receptors while escaping from immune system response can have chances to survive. Therefore, these critical mutations are the results of natural selection in virus evolution.

In the SARS-CoV-2 strains found in the US, the nucleocapsid (N) protein gene has three mutations (28881G > A, 28882G > A, and 28883G > C), The N protein of SARS-CoV is responsible for the formation of the helical nucleocapsid during virion assembly. The N protein may cause an immune response and has potential value in vaccine development [38]. These mutations shall be considered when developing a vaccine using the N protein.

3.2. Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus by genotyping

To spread, a pathogen virus must multiply within the host to ensure transmission, while simultaneously avoiding host morbidity or death. Therefore, during the evolution of a virus, the transmissibility of the virus is usually increased, whereas the pathogenicity becomes reduced [39]. From the SNP profiles of SARS-CoV-2 strain, high-frequency mutations predominate in the virus isolations, therefore, these high-frequency mutations probably contribute to increased transmissibility. In addition, these high-frequency mutations are associated with different critical proteins. This study analyzes and traces the SNP profiles from 558 SARS-CoV-2 strains which have at least 10 descendants. The result suggests a number of high-frequency mutations that are associated with different critical proteins. The results show that the SNP distribution is not random but is predominated at some positions and then have more descendants. These high-frequency mutations may confer a high transmissibility of the virus (Table 2 ). If we exclude the leader sequence mutation and the synonymous mutations (3037C > T, 8782C > T, 18060C > T), we classify the SNP mutations into four major groups based on the impacted proteins. (1) single mutation in nsp6 (11083G > T) (Fig. 2 ), (2) single mutation in ORF3a (26144G > T) (Fig. 3 ), (3) single mutation in RNA polymerase (nsp8) (8782C > T, 28144 T > C) (Fig. 4 ), and (4) double mutations in S-protein and RNA polymerase: (241C > T, 3037C > T, 14408C > T, 23403A > G) (Fig. 5 )). These strains in one group are derived from the same ancestor stain in that group according to their SNP profiles.

Table 2.

Co-mutations with high descendants in SARS-CoV-2.

| SNP co-mutations | proteins | descendants |

|---|---|---|

| 8782C > T, 28144 T > C, 18060C > T > C | RNA pol (nsp8) | 54 |

| 241C > T, 3037C > T, 23403A > G, 28144 T > C, | S protein, RNA pol (nsp8) | 82 |

| 241C > T, 3037C > T, 14408C > T, 23403A > G | RNA primase (nsp12), S protein | 81 |

Note: The SNP mutation positions are on the reference genome. Nucleotide T represents nucleotide U in SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome. The frequencies of mutations are computed from total SARS-CoV-2 strains.

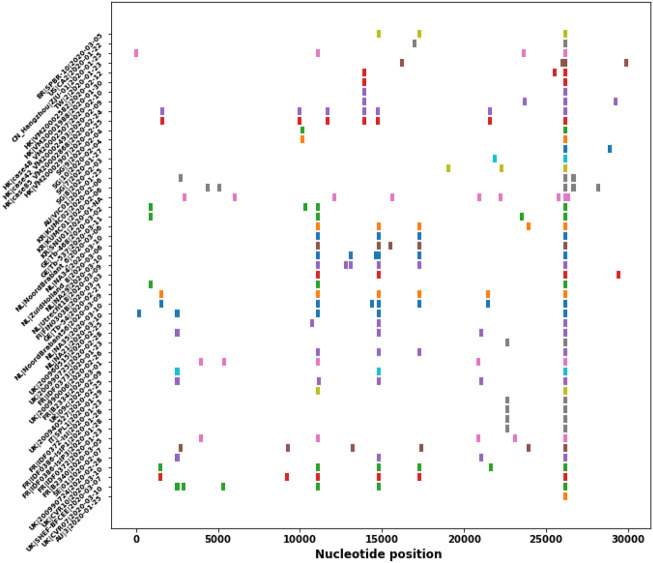

Fig. 2.

The SNP profiles of Genotype I (11083G > T). In y-axis, each row represents all SNPs in a SARS-CoV-2 strain. The strains from the same region are marked in the same color.

Fig. 3.

The SNP profiles of Genotype II (26144G > T). In y-axis, each row represents all SNPs in a SARS-CoV-2 strain. The strains from the same region are marked in the same color.

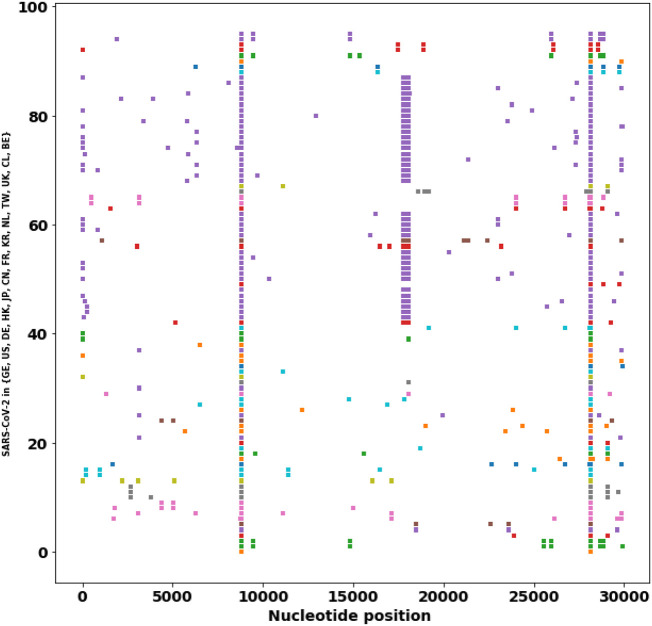

Fig. 4.

The SNP profiles of Genotype III (8782C > T, 28144 T > C). In y-axis, each row represents all SNPs in a SARS-CoV-2 strain. The strains from the same region are marked in the same color.

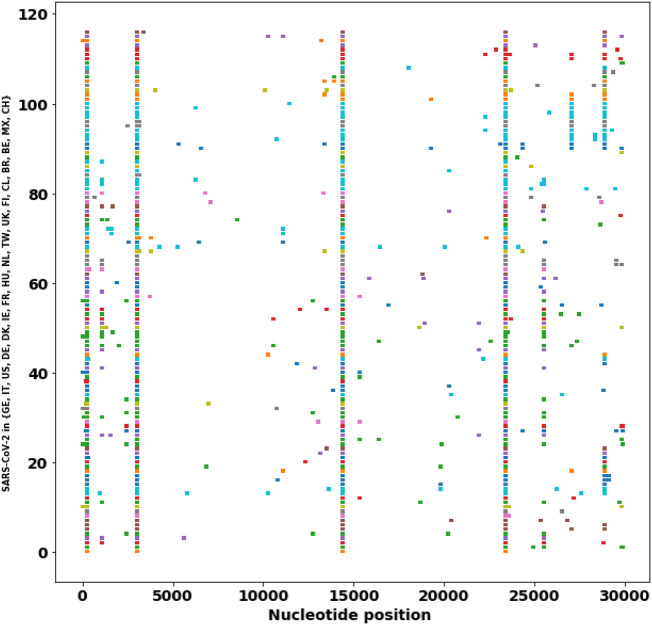

Fig. 5.

The SNP profiles of Genotype IV (241C > T, 3037C > T, 14408C > T, 23403A > G). In y-axis, each row represents all SNPs in a SARS-CoV-2 strain. The strains from the same region are marked in the same color.

The result shows that most SNP mutations in SARS-CoV-2 isolates in China and some from Europe and USA are located at two positions (8782C > T, 28144 T- > C) (Fig. 4). Later on this strain was mutated at new positions (8782C > T, 28144 T > C, 18060C > T). These mutations are from the early phase of the strain.

The important and prevalent co-mutations (241C > T, 3037C > T, 23403A > G) occurred mostly in SARS-CoV-2 isolates in European countries. This strain has additional extended mutations at positions (241C > T, 3037C > T, 14408C > T, 23403A > G) (Fig. 5)). The impacted critical proteins are NA pol (nsp8), RNA primase (nsp12), and the S protein. Most of the strains are found in European countries (Fig. 5). Italy is being heavily infected by SARS-CoV-2 with 59, 138 confirmed cases and 5, 476 deaths as of March 23, 2020 [2]. These critical mutations may be correlated with the severe infections in Europe.

From the SNP profiles of the viruses across the globe from a different time, we may estimate that one mutation can occur in one generation. For example, in USA (IL) two consecutive infection cases (US|IL1|EPI_ISL_404253|2020-01-21,US|IL2|EPI_ISL_410045|2020-01-28), the virus increased one mutation (28854C > Y) between two same community members. Over the length of its 30 kb genome, SARS-CoV-2 may accumulate mutations ranging from single mutation to 14 mutations (NL|EPI_ISL_413591|2020-03-02), as seen from December 2019 to March 23, 2020. Therefore, we may estimate that the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 has reached 14 generations since its first infection to humans in December 2019.

4. Discussions

This study employs the substitutions variants in genotyping for understanding the evolution and transmission of SARS-CoV-2, however, structural variants including insertions, deletions, and copy number variation are critical for virus pathogenicity [40] and human pathology [41,42]. The structural variants can also be retrieved from the MSA method. The deletion variants are observed in the SARS-CoV-2 strains, for example, US ∣ CA6 ∣ EPI_ISL_410044 ∣ 2020 − 01 − 27(508 − 522delTGGTCATGTTATGGT), UK ∣ 200690756 ∣ EPI_ISL_414044 ∣ 2020 − 02 − 08(1605 − 1607delATG), NL ∣ Rotterdam 1363790 ∣ EPI_ISL_413582 ∣ 2020 − 03 − 01(15595 − 1561delATG), IN ∣ 1 − 27 ∣ EPI_ISŁ413522 ∣ 2020 − 01 − 27(22978 − 22981delTAA), JP ∣ DP0037 ∣ EPI_ISL_416567 ∣ 2020 − 02 − 15(356 − 379delGGAGACTCCGTGGAGGAGGTCTTA). The tandem or dispersed repeats of copy number variants have not been observed in the SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Whether these structural mutations can spread is unknown given the limited genome data. The phenotype changes of these structural variants need further investigation.

The proposed genotyping method can reveal the SNPs patterns and structural variants of virus isolates during evolution. The method may also be applied to unravel the evolutionary genetics of zoonotic jumps so that infectious diseases can be prevented. Identification and comparison of the SNPs in the Spike protein genes of SARS-CoV-2 and bat-CoVs using the reference genome of a putative ancestral bat-CoV, for example, pangolins-Cov, will provide insights on the genetic mechanisms in the zoonotic jump of SARS-CoV-2.

A few notable limitations in this study due to the nature of the genome data shall be noted. Because the sample collection dates may not reflect the actual infection date so the transmission path analysis is only an approximation. Caution should be exercised on the genotyping analytics because some countries have not sequenced enough virus samples, the frequencies of the genotype groups may be unbalanced due to the unavailability of complete genomes in some countries and regions. Whether any of these common SNP mutations will result in biological and clinical differences remains to be determined.

In this study, the complete genomes of SARS-CoV-2 are used for SNP genotype calling. However, in times of crisis, complete genomes may not be available for SNP genotyping. In this case, the SNP variant calling process may directly use the raw NGS reads [32]. The SNP variants then can be obtained by mapping the NGS reads to the reference genome by BWA alignments [43], followed by GATK variant calling [44].

5. Conclusion

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has caused a substantial health emergency and economic stress in the world. Therefore, understanding the nature of this virus and deriving methods to monitor the spread of virus in the pandemic are critical in disease control. Our results show several molecular facets of the SARS-CoV-2 pertinent to this pandemic. The discovery of genotypes linked to geographic and temporal infectious clusters suggests that genome SNP signatures can be used to track and monitor the transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

Rapid detection of different genotypes of SARS-CoV-2 are important for an efficient response to the COVID-19 outbreak. Discriminating and relating viral isolates can be useful in genetic epidemiology. Determining the origin and monitoring the transmission pattern of the pathogenic agents are critical to controlling the outbreak. In this work, the SNP genotyping of SARS-CoV-2 was developed by adapting fast MSA of the complete genomes of SARS-CoV-2 and SNP analytics using the directed Jaccard distance of the SNP profiles. The genotyping analysis provides insights on the frequent mutations that confer fast transmissibility of the virus. The major mutations are in the critical proteins, including the S protein, RNA polymerase, RNA primase, and nucleoprotein. Therefore, these high-frequency SNP mutation sites must be considered when designing a vaccine for preventing the infection of SARS-CoV-2.

Acknowledgments

The author sincerely appreciates the researchers worldwide who sequenced and shared the complete genome data of SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses from GISAID (https://www.gisaid.org/). This research is dependent on these precious data. The references of the genomes are in the supplementary material (gisaid_cov2020_acknowledgement_table.csv). The author thanks four anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.04.016.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Gorbalenya A. The species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . Coronavirus Disease (COVID-2019) Situation Reports 00 (00) 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report – 63. (00–00) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J. Pathogenicity and transmissibility of 2019-nCoV — a quick overview and comparison with other emerging viruses. Microbes Infect. 2020;22(2):69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li T., Zhang Y., Fu L., Yu C., Li X., Li Y., Zhang X., Rong Z., Wang Y., Ning H. siRNA targeting the leader sequence of SARS-CoV inhibits virus replication. Gene Therapy. 2005;12(9):751–761. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y., Liu Q., Guo D. Emerging coronaviruses: genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:418–423. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serrano P., Johnson M.A., Chatterjee A., Neuman B.W., Joseph J.S., Buchmeier M.J., Kuhn P., Wüthrich K. Nuclear magnetic resonance structure of the nucleic acid-binding domain of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nonstructural protein 3. J. Virol. 2009;83(24):12998–13008. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01253-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lei J., Kusov Y., Hilgenfeld R. Nsp3 of coronaviruses: structures and functions of a large multi-domain protein. Antivir. Res. 2018;149:58–74. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anand K., Ziebuhr J., Wadhwani P., Mesters J.R., Hilgenfeld R. Coronavirus main proteinase (3CLpro) structure: basis for design of anti-SARS drugs. Science. 2003;300(5626):1763–1767. doi: 10.1126/science.1085658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim Y., Lovell S., Tiew K.-C., Mandadapu S.R., Alliston K.R., Battaile K.P., Groutas W.C., Chang K.-O. Broad-spectrum antivirals against 3C or 3C-like proteases of picornaviruses, noroviruses, and coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2012;86(21):11754–11762. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01348-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen D.D., Gao K., Wang R., Wei G. Machine intelligence design of 2019-nCoV drugs. bioRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angelini M.M., Akhlaghpour M., Neuman B.W., Buchmeier M.J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nonstructural proteins 3, 4, and 6 induce double-membrane vesicles. MBio. 2013;4(4) doi: 10.1128/mBio.00524-13. (e00524–13) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Te Velthuis A.J., van den Worm S.H., Snijder E.J. The SARS-coronavirus nsp7+ nsp8 complex is a unique multimeric RNA polymerase capable of both de novo initiation and primer extension. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(4):1737–1747. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prentice E., McAuliffe J., Lu X., Subbarao K., Denison M.R. Identification and characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replicase proteins. J. Virol. 2004;78(18):9977–9986. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.18.9977-9986.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutton G., Fry E., Carter L., Sainsbury S., Walter T., Nettleship J., Berrow N., Owens R., Gilbert R., Davidson A. The nsp9 replicase protein of SARS-coronavirus, structure and functional insights. Structure. 2004;12(2):341–353. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li K.-F., Wu H., Yan H., Ma S., Wang L., Zhang M., Tang X., Temperton N.J., Weiss R.A., Brenchley J.M. T cell responses to whole SARS coronavirus in humans. J. Immunol. 2008;181(8):5490–5500. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marra M.A., Jones S.J., Astell C.R., Holt R.A., Brooks-Wilson A., Butterfield Y.S., Khattra J., Asano J.K., Barber S.A., Chan S.Y. The genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. 2003;300(5624):1399–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruan Y., Wei C.L., Ling A.E., Vega V.B., Thoreau H., Thoe S.Y.S., Chia J.-M., Ng P., Chiu K.P., Lim L. Comparative full-length genome sequence analysis of 14 SARS coronavirus isolates and common mutations associated with putative origins of infection. Lancet. 2003;361(9371):1779–1785. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13414-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wan Y., Shang J., Graham R., Baric R.S., Li F. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J. Virol. 2020;94(7) doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong S.K., Li W., Moore M.J., Choe H., Farzan M. A 193-amino acid fragment of the SARS coronavirus S protein efficiently binds angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(5):3197–3201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300520200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coutard B., Valle C., de Lamballerie X., Canard B., Seidah N., Decroly E. The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in CoV of the same clade. Antivir. Res. 2020;176:104742. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J., Sun Y., Qi J., Chu F., Wu H., Gao F., Li T., Yan J., Gao G.F. The membrane protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus acts as a dominant immunogen revealed by a clustering region of novel functionally and structurally defined cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitopes. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;202(8):1171–1180. doi: 10.1086/656315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He R., Leeson A., Ballantine M., Andonov A., Baker L., Dobie F., Li Y., Bastien N., Feldmann H., Strocher U. Characterization of protein–protein interactions between the nucleocapsid protein and membrane protein of the SARS coronavirus. Virus Res. 2004;105(2):121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guan W.-j., Ni Z.-y., Hu Y., Liang W.-h., Ou C.-q., He J.-x., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C.-l., Hui D.S. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Domingo E., Holland J. RNA virus mutations and fitness for survival. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1997;51(1):151–178. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holmes E.C., Rambaut A. Viral evolution and the emergence of SARS coronavirus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004;359(1447):1059–1065. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shu Y., McCauley J. GISAID: Global initiative on sharing all influenza data–from vision to reality. Eurosurveillance. 2020;22(13) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.13.30494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sievers F., Higgins D.G. Multiple Sequence Alignment Methods. Springer; 2014. Clustal Omega, accurate alignment of very large numbers of sequences; pp. 105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.-M., Wang W., Song Z.-G., Hu Y., Tao Z.-W., Tian J.-H., Pei Y.-Y. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levandowsky M., Winter D. Distance between sets. Nature. 1971;234(5323):34. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Comas I., Homolka S., Niemann S., Gagneux S. Genotyping of genetically monomorphic bacteria: DNA sequencing in mycobacterium tuberculosis highlights the limitations of current methodologies. PLoS One. 2009;4(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu C., Baune B.T., Licinio J., Wong M.-L. A novel strategy for clustering major depression individuals using whole-genome sequencing variant data. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:44389. doi: 10.1038/srep44389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin C., Yau S.S.-T. Whole genome single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping of staphylococcus aureus. Commun. Inf. Syst. 2019;19(1):57–80. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cock P.J., Antao T., Chang J.T., Chapman B.A., Cox C.J., Dalke A., Friedberg I., Hamelryck T., Kauff F., Wilczynski B. Biopython: freely available python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1422–1423. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang L., Shen F.-m., Chen F., Lin Z. Origin and evolution of the 2019 novel coronavirus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao X., Chakraborti S., Dimitrov A.S., Gramatikoff K., Dimitrov D.S. The SARS-CoV s glycoprotein: expression and functional characterization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;312(4):1159–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Follis K.E., York J., Nunberg J.H. Furin cleavage of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein enhances cell–cell fusion but does not affect virion entry. Virology. 2006;350(2):358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfeiffer J.K., Kirkegaard K. A single mutation in poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase confers resistance to mutagenic nucleotide analogs via increased fidelity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100(12):7289–7294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232294100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao P., Cao J., Zhao L.-J., Qin Z.-L., Ke J.-S., Pan W., Ren H., Yu J.-G., Qi Z.-T. Immune responses against SARS-coronavirus nucleocapsid protein induced by DNA vaccine. Virology. 2005;331(1):128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alizon S., Hurford A., Mideo N., Van Baalen M. Virulence evolution and the trade-off hypothesis: history, current state of affairs and the future. J. Evol. Biol. 2009;22(2):245–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeDiego M.L., Pewe L., Alvarez E., Rejas M.T., Perlman S., Enjuanes L. Pathogenicity of severe acute respiratory coronavirus deletion mutants in hACE-2 transgenic mice. Virology. 2008;376(2):379–389. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu C., Baune B.T., Wong M.-L., Licinio J. Investigation of copy number variation in subjects with major depression based on whole-genome sequencing data. J. Affect. Disord. 2017;220:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu C., Baune B.T., Wong M.-L., Licinio J. Investigation of short tandem repeats in major depression using whole-genome sequencing data. J. Affect. Disord. 2018;232:305–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H. 2013. Aligning Sequence Reads, Clone Sequences and Assembly Contigs With BWA-MEM. (arXiv preprint arXiv:1303.3997) [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKenna A., Hanna M., Banks E., Sivachenko A., Cibulskis K., Kernytsky A., Garimella K., Altshuler D., Gabriel S., Daly M. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material