Abstract

Background.

We investigated whether caspofungin and other echinocandins have immune-enhancing properties that influence human polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN)–mediated mold hyphal damage.

Materials and methods.

Using aniline blue staining, we compared patterns of β-glucan exposure in Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus terreus, Rhizopus oryzae, Fusarium solani, Fusarium oxysporum, Scedosporium prolificans, and Scedosporium apiospermum hyphae after caspofungin exposure. We also determined PMN-mediated hyphal damage occurring with or without preexposure to caspofungin or with preexposure to the combination of caspofungin and anti–β-glucan monoclonal antibody, using 2,3-bis (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino) carbonyl]-sH-tetrazolium hydroxide (XTT) assay.

Results.

Preincubation with caspofungin (32 μ g/mL for R. oryzae; 0.0625 μ g/mL for other isolates) increased exposure to β-glucan. PMN-induced damage increased after caspofungin exposure and was further augmented by the addition of anti–β-glucan antibody. Preincubation with micafungin or anidulafungin had similar effects on PMN-induced damage of A. fumigatus hyphae. Finally, preexposure of A. fumigatus, but not S. prolificans, to caspofungin induced expression of Dectin-1 by PMN.

Conclusions.

The results of the present study suggest inducement of β-glucan unmasking by echinocandins and enhancement of PMN activity against mold hyphae, thereby supporting the immunopharmacologic mode of action of echinocandins.

Invasive mold infections are major causes of morbidity and mortality among severely immunocompromised individuals [1–3]. Aspergillus fumigatus remains the most prevalent mold in this patient population, whereas other opportunistic molds, such as Fusarium species,Scedosporium species, and Zygomycetes organisms are increasingly reported to be causative agents of invasive fungal infections [1–3]. Although caspofungin, an echinocandin approved for the treatment of infections due to Aspergillus and Candida species [4], demonstrates minimal activity in vitro against Zygomycetes and other non-Aspergillus hyalohyphomycetes [5], surprising efficacy has been reported in experimental models of infections due to non-Aspergillus mold [6–8].

Echinocandins exhibit a unique, fungus-specific mechanism of action by targeting 1,3-β-D-glucan synthase [4, 9], thereby inhibiting the biosynthesis of 1,3-β-D-glucan, an important component of the fungal cell wall. In addition to having a structural role, β-glucan exhibits potent immunostimulatory properties mediated by the innate immune receptor Dectin-1 [10]. Dectin-1 modulates immune effector cell activity against a variety of fungi, along with other germline pattern recognition receptors, such as Toll-like receptor (TLR)–2 and TLR-4 [10]. Collectively, these receptors play a key role in orchestrating immune responses tailored for the stage-specific growth (swollen conidia, germlings, and hyphae) of fungal pathogens [10–14].

Studies of Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have revealed an echinocandin-susceptible genetic network that conceals β-glucan from the immune system, thus limiting an effective host response [15]. Although a similar drug-susceptible network for masking β-glucans has not been described in molds, a growing body of evidence suggests that β-glucan also plays a key role in the innate host immune response against A. fumigatus [16, 17]. In the present study, we assessed the effects of incubating the hyphae of various clinically important molds with caspofungin on β-glucan exposure in the fungal cell wall. We also assessed the hyphal damage induced by polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) when previous echinocandin incubation with or without a monoclonal antibody targeting β-glucan in the fungal cell wall occurred. Finally, we examined whether preexposure of A. fumigatus to caspofungin results in the induction of receptors (e.g., Dectin-1, TLR-2, and TLR-4) associated with the immune response against fungi.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patterns of β-glucan exposure.

Patterns of β-glucan exposure in the fungal cell wall were assessed in the hyphae of 6 clinical mold isolates (Aspergillus terreus, Scedosporium apiospermum, Scedosporium prolificans, Fusarium solani, Fusarium oxysporum, and Rhizopus oryzae) and A. fumigatus (strain Af293), by use of aniline blue, a fluorescent dye that stains linear cell wall glucans, including 1,3-β-glucan [18]. After determining the minimum effective concentration (MEC) of caspofungin for all isolates (0.06 μ g/mL for strain Af293, 0.0125 μ g/mL for A. terreus, 16 μ g/mL for S. apiospermum, >32 μ g/mL for S. prolificans, 16 μ g/mL for F. solani, 16 μ g/mL for F. oxysporum, and >32 μ g/mL for R. oryzae), we grew fungal conidia (1 × 105 conidia/mL) in RPMI 1640 medium plus 10% glucose plus 0.15% polyacrylate Junlon dispersal agent (wt/vol) for 12–16 h at 37°C [19]. Hyphal germlings were then centrifuged (at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4°C) and washed with PBS-Junlon solutions before the addition of fresh medium containing 2-fold–increasing serial concentrations of caspofungin (0.031–64 μ g/mL). Fungal hyphae were incubated for an additional 6 h before they were washed and resuspended in PBS-Junlon plus 0.1 mg/mL aniline blue. After incubation in the dark for 5 min at room temperature, the hyphae were washed in PBS-Junlon, and total fluorescence was determined in relation to media and drug-free controls on 96-well Optiplates (Packard), by use of a Biotek FL600 spectrofluorometer (Biotek Instruments) with an excitation wavelength of 400 nm per slit width of 30 and an emission wave length of 460 nm per slit width of 40. Microscopy was performed in parallel, with an Olympus BX51 triple-band fluorescence microscope.

PMN isolation and PMN killing assays.

PMNs in the heparinized whole blood of one healthy volunteer were isolated by means of ficoll-hypaque centrifugation, as described elsewhere[20]. PMNs from 2 additional healthy volunteers were used for selected experiments. PMN viability (>95%) was verified by tryptan blue staining. PMNs were diluted to a final concentration of 106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 plus 10% fetal calf serum medium. Mature hyphae of the 6 aforementioned clinical mold isolates were generated after incubation of 105 conidia in 1-mL aliquots of RPMI 1640 plus 10% fetal calf serum media in a shaking incubator for 18 h at 37°C.

For each isolate, the killing efficacy of PMNs against hyphae was assessed by an 2,3-bis (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)5-[(phenylamino) carbonyl]-sH-tetrazolium hydroxide (XTT)–based colorimetric assay, as described elsewhere [21]. In brief, hyphae of each isolate were incubated for 1 h with 106 PMNs (effector:target ratio, 10:1) suspended in RPMI 1640 plus 10% fetal calf serum. After incubation, PMNs were lysed hypotonically, and PMN-induced hyphal damage was calculated according to the following formula: percentage of hyphal damage [H11005] [1 [H11002] X/C] × 100, where X denotes the optical density of test wells and where C denotes the optical density of control wells with hyphae not exposed to PMNs. Optical density at both 492 and 690 nm (plate absorbance) was measured using a microplate spectrophotometer (Power Wave X; Biotech Instruments).

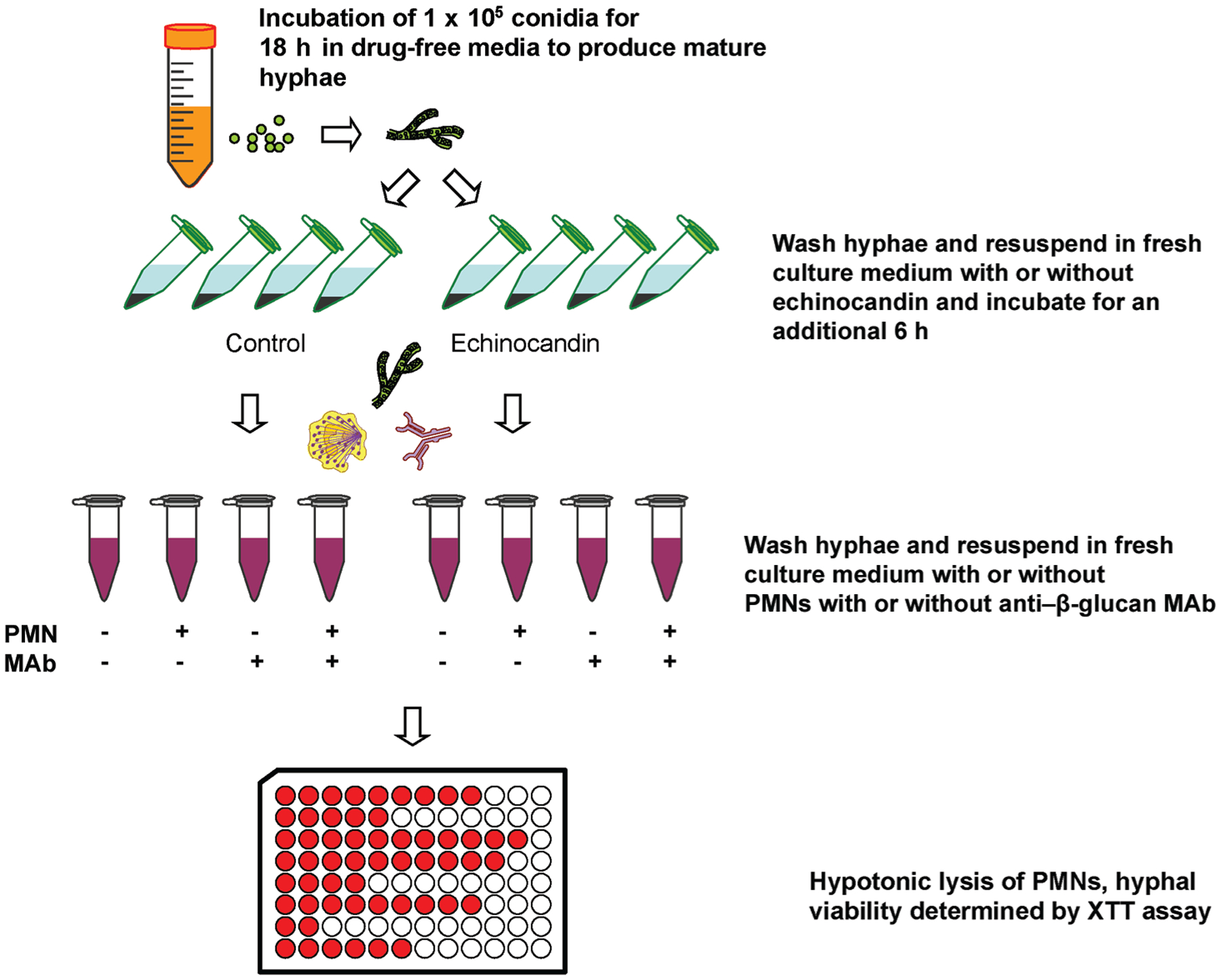

The activity of PMNs against fungal hyphae was also assessed after preexposure to an anti–[H9252]-glucan antibody and/or an echinocandin. Mature hyphae were prepared as described above, washed, and then resuspended in RPMI 1640 plus 10% fetal calf serum solution containing fixed concentrations of caspofungin (0.0625 and 32 μ g/mL for R. oryzae; 0.0625 μ g/mL for all other isolates), micafungin (0.0625 μ g/mL), or anidulafungin (0.0625 μ g/mL), on the basis of our findings obtained from fluorescence microscopy, for 6 h before the addition of PMNs, whereas controls were resuspended in RPMI 1640 plus 10% fetal calf serum for another 6 h. Monoclonal anti–β-glucan antibody (0.1 mg/mL; Biosupplies) was added 1 h before the addition of PMNs. All experiments were performed at least in triplicate (fig 1).

Figure 1.

Depiction of assessment of polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN)–induced hyphal damage after preexposure to subinhibitory echinocandin concentrations with or without antiglucan monoclonal antibodies (MAbs). XTT, 2,3-bis (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino) carbonyl]-sH-tetrazolium hydroxide.

Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis for expression of Dectin-1, TLR-2, and TLR-4 genes.

For quantitative RT-PCR assessment of gene expression, 106 PMNs were exposed to strain Af293 and S. prolificans hyphae (either exposed or not exposed to 0.0625 μ g/mL caspofungin for 6 h) for 1 h (effector:target ratio, 10:1). Total RNA from PMNs was extracted using a commercial kit (RNeasy). Subsequently, differences in Dectin-1, TLR-2, and TLR-4 expression induced by exposure to caspofungin were assessed by RT-PCR, as described elsewhere [22]. PMNs were collected and total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Protect mini kits (Qiagen). Reverse transcription was performed (GeneAmp RNA PCR kit; Applied Biosystems), and relative gene expression was determined using real-time PCR SYBR green detection (with the use of an ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system) and primers and probes specific for DNA encoding TLR-2 (5’- GGCCAGCAAATTACCTGTGTG-3’ and 5’-AGGCGGACATCCTGAACCT-3’), TLR-4 (5’-CTGCAATGGATCAAGGACCA-3’ and 5’-TTATCTGAAGGTGTTGCACATTCC-3’), Dectin-1 (5’- TGGCAACTGGGCTCTAATCTCCT-3’ and 5’-TTTCTTGGGTAGCTGTGGTTCTGA-3’), and β−2 microglobin (as control) (5’-CTCCGTGGCCTTAGCTGTG-3’ and 5’-TTTGGAGTACGCTGGATAGCCT-3’). The specificity of products was confirmed by melt-curve analysis. Figure 1 depicts the experimental strategy.

Statistical analysis.

For analysis of each data set and for comparison between different groups, we used 1-way analysis of variance and then Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test with a 99% confidence interval. We performed all statistical analyses using GraphPad Prism software (version 4.0), and P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant. We conducted all experiments in triplicate at different times.

RESULTS

Cell wall β-glucan exposure in hyphae increases after treatment with caspofungin.

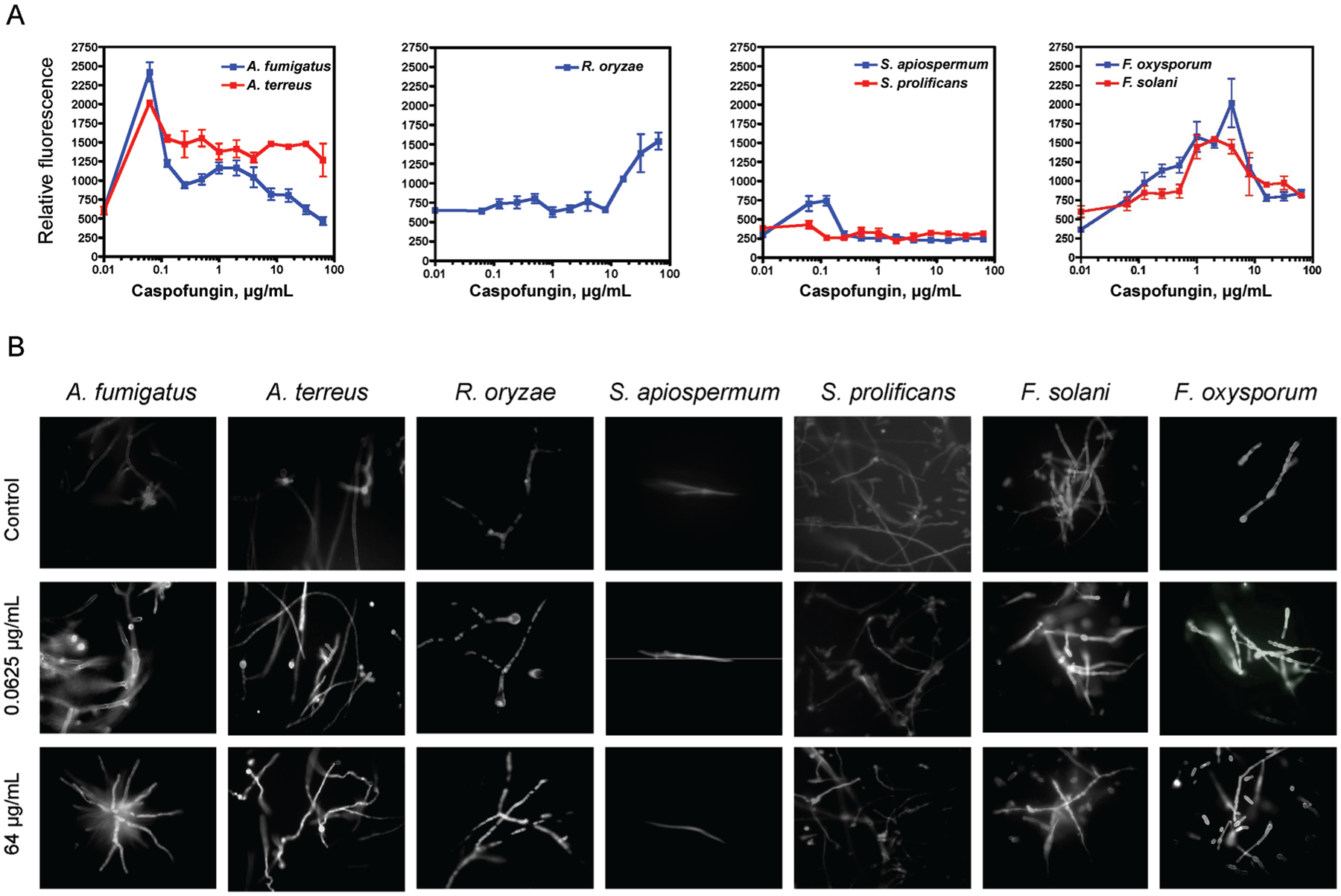

In all isolates, except for S. prolificans isolates, exposure to increasing concentrations of caspofungin (0.1–100 μ g/mL) resulted in concentration-dependent changes in β-glucan exposure in hyphae (figure 2). In contrast, in all non–caspofungin-exposed isolates, minimal fluorescence was seen only in apical hyphal tips. In A. fumigatus, A. terreus, and S. apiospermum, exposure to caspofungin resulted in concentration dependent increases in apical and subapical hyphal compartment fluorescence that was maximal at a caspofungin concentration of 0.0625 μ g/mL. Although fluorescence peaked in the aforementioned concentration, exposure to higher caspofungin concentrations resulted in a reduction of measured fluorescence (figure 2). In F. solani and F. oxysporum, β-glucan–associated fluorescence increased up to a caspofungin concentration of 16 μ g/mL. In R. oryzae, although fluorescence did not increase over caspofungin concentrations of 0.01–16 μg/mL, apical and subapical hyphal compartment fluorescence was observed in concentrations of 32–64 μ g/mL. In S. prolificans, increasing concentrations of caspofungin did not exert any effect on the fluorescence pattern, compared with non–caspofungin-exposed control.

Figure 2.

Exposure of molds to caspofungin and increases in β-glucan exposure. A, Measured β-glucan fluorescence after aniline blue staining, after 6 h of incubation with increasing concentrations of caspofungin. B, Fluorescence micrographs demonstrating increasing apical and subapical hyphal compartment fluorescence after exposure to concentrations of caspofungin.

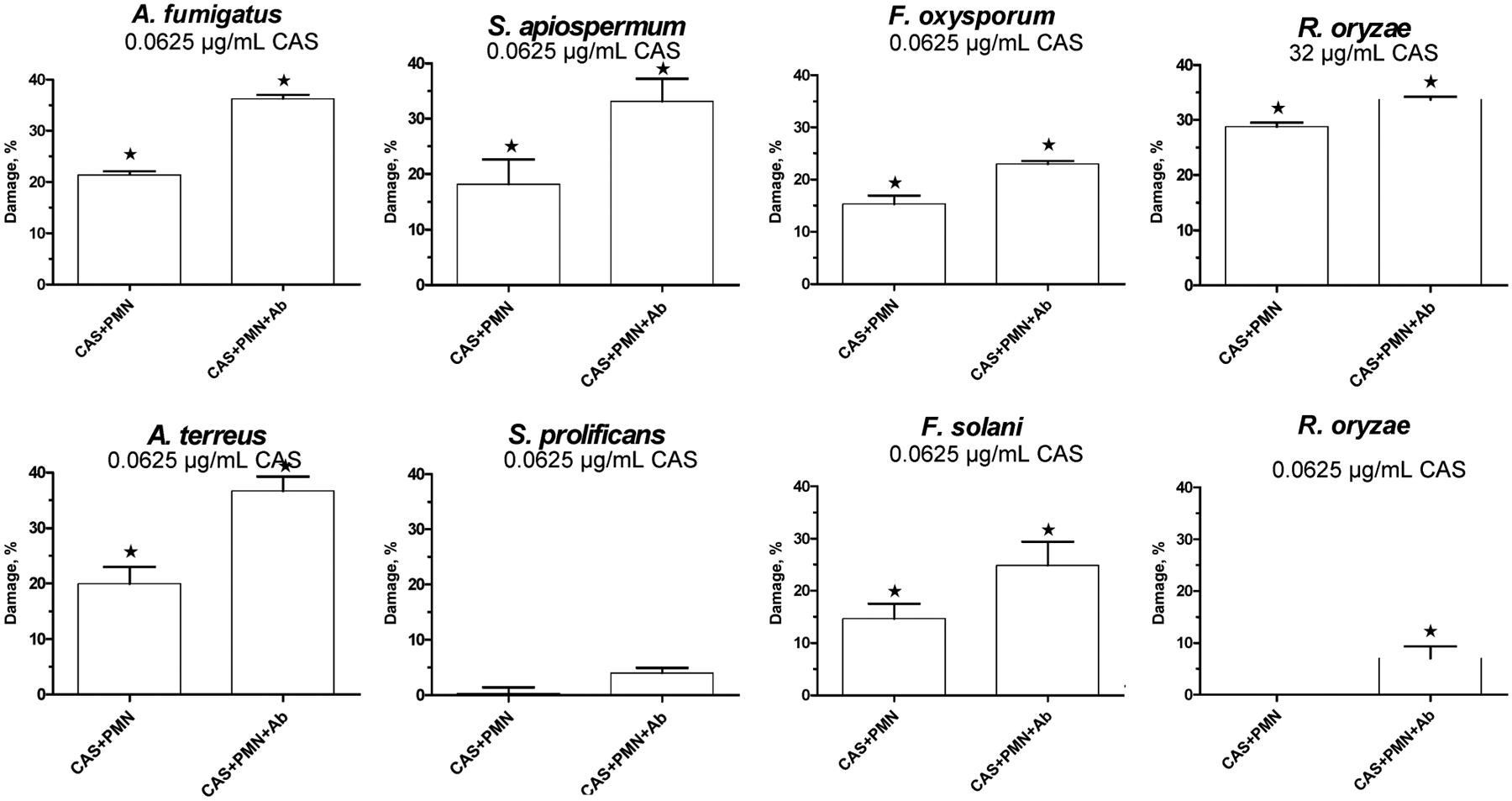

Preexposure to caspofungin enhances PMN-mediated hyphal damage in all molds, with the exception of S. prolificans.

For A. fumigatus, coincubation with PMNs resulted in a 37% reduction in hyphal viability (as determined by XTT assay). Previous exposure of hyphae to 0.0625 μ g/mL caspofungin further reduced hyphal viability by an additional 22% (P < .0001) (figure 3). In addition, with the use of PMNs from 2 other healthy volunteers, the mean PMN-induced reduction in hyphal viability was 37%, whereas previous exposure of hyphae to caspofungin resulted in a 31% increase in damage after incubation with PMNs (P < .0001). For A. terreus, coincubation with PMNs alone reduced hyphal viability by 35%. Preexposure to caspofungin reduced hyphal viability by an additional 20% (P < .0001).

Figure 3.

Exposure of molds to caspofungin and anti–β-glucan antibody enhances polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN)–mediated hyphal damage. Hyphae were exposed to PMNs for 1 h without pretreatment with either anti–β glucan antibody or caspofungin (control), after 6 h of coincubation with caspofungin or after pretreatment with both caspofungin (for 6 h) and anti β-glucan antibody (for 1 h) before the addition of PMNs. Data are expressed in terms of the percentage increase in PMN hyphal damage vs. control. *P < .05, compared with control (PMNs alone). Ab, antibody; A. fumigatus, Aspergillus fumigatus; A. terreus, Aspergillus terreus; CAS, caspofungin; F. oxysporum, Fusarium oxysporum; F. solani, Fusarium solani; R. oryzae, Rhizopus oryzae; S. apiospermum, Scedosporium apiospermum; S. prolificans, Scedosporium prolificans.

Similarly, for Fusarium species, previous exposure of hyphae to caspofungin increased vulnerability to PMNs. For F. solani, PMNs alone resulted in mean hyphal damage of 30%. Previous exposure to 0.0625 μ g/mL caspofungin increased hyphal damage after incubation with PMNs by an additional 15% (P = .029). For F. oxysporum, incubation with PMNs resulted in mean hyphal damage of 23%. Preexposure to caspofungin(0.0625 μ g/mL) increased PMN-induced hyphal damage by 15% (P < .0001).

For S. apiospermum, incubation with PMNs resulted in median hyphal damage of 38%. Previous exposure to 0.0625μ g/mL caspofungin before the addition of PMNs increased damage by 19% (P <.0001). For S. prolificans, PMNs alone caused mean hyphal damage of 41%. Incubation with caspofungin did not significantly alter the damage induced by PMNs.

For R. oryzae, incubation of hyphae with PMNs resulted in mean measured hyphal damage of 31%. Previous incubation with 32 μ g/mL caspofungin increased measured PMN-induced damage by 28% (P < .0001), whereas preincubation with 0.0625 μ g/mL caspofungin did not have any significant effect on PMN-induced damage (P = not significant [NS]).

Enhancement of PMN-mediated hyphal damage in A. fumigatus after preexposure to micafungin or anidulafungin.

For A. fumigatus, previous exposure of hyphae to 0.0625μ g/mL micafungin for 6 h increased the damage induced by PMNs by 26% (P <.0001). Similarly, previous hyphal exposure to 0.0625 μ g/mL anidulafungin for 6 h also increased the damage induced by PMNs by 30% (P < .0001). Incubation of hyphae with micafungin alone for 6 h resulted in mean measured damage of 21%, whereas, after 6 h of exposure to anidulafungin, mean measured damage was 18%.

Enhancement of PMN-induced hyphal damage and augmentation of PMN activity against caspofungin preexposed molds by anti-β-glucan monoclonal antibody.

In all isolates, except for S. prolificans, incubation with anti–β-glucan antibody 1 h before the addition of PMNs modestly increased PMN induced hyphal damage (figure 3). PMN-induced damage was further enhanced when hyphae were preexposed to both anti–β-glucan antibody and caspofungin. Specifically for A. fumigatus, the addition of anti–β-glucan antibody before incubation with PMNs increased measured hyphal damage by 5% (P < .0001), whereas preexposure to the combination of caspofungin and anti–[H9252]-glucan antibody increased PMN-induced hyphal damage by 36% (P < .0001) (figure 3). For A. terreus, the addition of anti–β-glucan antibody increased hyphal damage by 11% (P < .0001), whereas the combination of preexposure to caspofungin and 1 h of incubation with anti–β-glucan antibody resulted in a total increase in hyphal damage of 36%, compared with PMNs alone (P < .0001).

For F. solani, hyphal damage induced by PMNs increased by 9% with the addition of anti–β-glucan antibody (P = .0116). Exposure to both caspofungin and anti–β-glucan antibody before PMN incubation augmented induced hyphal damage by 25% (P < .0001). Similarly, for F. oxysporum, the addition of anti–β-glucan antibody increased PMN-induced hyphal damage by 6% (P < .0001), and, if anti–β-glucan antibody was combined with caspofungin exposure before the addition of PMNs, hyphal damage increased by 23% (P < .0001).

For S. apiospermum, the mean hyphal damage measured after incubation with PMNs increased by 13% with the addition of anti–β-glucan antibody (P = .0003). The combination of caspofungin and anti–β-glucan antibody increased measured hyphal damage by 33% (P < .0001). For S. prolificans, the addition of anti–β-glucan antibody before incubation with PMNs resulted in a minimal increase in hyphal damage (1%; P = NS), whereas exposure to the combination of caspofungin and anti–β-glucan antibody resulted in a mean increase in PMN-induced hyphal damage of 4% (P = NS).

For R. oryzae, the addition of anti–β-glucan antibody before incubation with PMNs increased PMN-induced hyphal damage by only 2% (P = .02), whereas exposure to the combination of caspofungin (32 μ g/mL) and anti–β-glucan antibody augmented PMN-induced hyphal damage by 32% (P < .0001). On the contrary, incubation with 0.0625 μ g/mL caspofungin did not further increase PMN-induced damage, compared with anti–β-glucan antibody alone.

Amplification of Dectin-1 mRNA expression in PMNs after incubation with caspofungin preexposed A. fumigatus but not S. prolificans hyphae.

Exposure of PMNs to A. fumigatus hyphae for 1 h resulted in modest (1.5-fold) increases in the expression of Dectin-1, but not in the expression of TLR-2 or TLR-4, compared with expression at baseline, as measured by RT-PCR. Incubation of A. fumigatus hyphae with 0.0625 μ g/mL caspofungin for 6 h before the addition of PMNs resulted in a 3-fold increase in Dectin-1 mRNA expression in PMNs, compared with expression at baseline, whereas no additional increase in TLR-2 or TLR-4 expression was observed, compared with PMN incubation with hyphae not exposed to caspofungin.

Similarly, exposure of PMNs to S. prolificans hyphae for 1 h resulted in a 1.5-fold increase in Dectin-1 and a 1-fold increase in the expression of TLR-2 and TLR-4, compared with expression at baseline. However, previous incubation of hyphae with 0.0625 μ g/mL caspofungin did not result in any additional increase in Dectin-1, TLR-2, and TLR-4 mRNA expression, compared with PMN incubation with hyphae not exposed to caspofungin.

DISCUSSION

Caspofungin, an echinocandin, exhibits its action by inhibiting glucan synthesis and thus lowering bulkβ-glucan cell levels [23]. This action upsets the equilibrium required to maintain cell wall architecture, ultimately causing increased β-glucan exposure [15, 24]. In our experiments, exposure of Aspergillus species, Fusarium species, and S. apiospermum to a subinhibitory concentration of caspofungin (0.0625 μ g/mL) resulted in a marked increase in β-glucan exposure that was associated with a significant increase in PMN-mediated hyphal damage.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the immunopharmacologic effect of caspofungin against clinically important non-Aspergillus molds, against which the drug has no demonstrable in vitro activity [5]. We found that, in all the mold strains that we tested, except for S. prolificans, incubation with increasing concentrations of caspofungin resulted in increases in β-glucan exposure, as measured by fluorescence. Our results are in agreement with recent studies showing that, in C. albicans[15] and A. fumigatus [25], exposure to subinhibitory concentrations of caspofungin heightens β-glucan exposure. The decrease in relative fluorescence seen with increasing concentrations of caspofungin against some molds (figure 2) could be attributed to a decrease in β-glucan synthesis in that range of concentrations.

We also found that exposure to caspofungin concentrations associated with increased surface β-glucan staining correlated with significantly enhanced PMN-induced hyphal damage, independent of the growth inhibitory effects (e.g., MIC or MEC) of these agents. This effect was class specific, because anidulafungin and micafungin also enhanced PMN-mediated hyphal damage. In a recent study, micafungin was found to have an additive effect with PMN-induced damage in A. fumigatus hyphae [26]. In another study assessing the interaction of caspofungin with immune effector cells, caspofungin was found to enhance monocyte and macrophage activity against A. fumigatus, albeit not PMN-mediated damage, although there was a trend toward synergistic interaction of caspofungin with PMNs [27].

Furthermore, we assessed the role of targeting β-glucan in the fungal cell wall with anti–β-glucan antibody as a means of further improving the immunomodulating effect of the echinocandins. In all molds tested, except for S. prolificans, anti–β-glucan antibody enhanced PMN-induced hyphal damage. Anti–β- glucan antibodies have been detected in the sera of patients and in animal models of invasive candidiasis [28], possibly playing a key role in orchestrating immune responses by promoting phagocytosis, enhancing antigen and costimulatory molecule presentation and modulation of host cytokine production [29]. Our data also suggest that glucans are important constituents of the fungal cell wall not only in Aspergillus species but, also, in other clinically important molds, such as Zygomycetes organisms [6], Fusarium species [30], and Scedosporium species [9].

β-glucans have been implicated as fungus-derived targets of mammalian innate immune receptors, such as Dectin-1 [13]. Specifically, Dectin-1 binds to β-glucan from Pneumocystis jirovecii [31], C. albicans [32], Coccidioides posadasii [33], and A. fumigatus [17], resulting in phagocytic and proinflammatory responses [13]. Dectin-1 and TLRs have been found to permit immune effector cells to distinguish between specific morphological characteristics of A. fumigatus [16]. In the present study, caspofungin-induced β-glucan exposure was associated with enhanced PMN hyphal damage and up-regulation of Dectin-1 expression. The relatively low expression of a Dectin-1–encoding gene could be explained by the fact that Dectin-1 is preferentially induced by swollen conidia and germlings and not by mature hyphae [32].

It is important to point out that we used PMNs from only one healthy volunteer, to limit variability in most of our experiments. Polymorphisms in the TLR and, possibly, in Dectin-1 germline genes have been reported to affect the host response against fungal pathogens [34]. Therefore, it is possible that some hosts may derive less immunologic benefit from echinocandins. Nevertheless, PMN-mediated hyphal damage of A. fumigatus hyphae was reproducibly enhanced by caspofungin preincubation when PMNs from 2 additional volunteers were tested.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate the effect of caspofungin in increasing β-glucan exposure in the cell wall, as well as in enhancing PMN-induced hyphal damage in molds. Unlike other antifungal agents that directly enhance immune effector cells [35, 36], echinocandins seem to uniquely exert their immunomodulating properties in the presence of damaged hyphal lesions. Given that echinocandin efficacy is not fully captured by such conventional methods as MIC determination [37], our findings are consistent with the notion that these compounds collaborate with and enhance the actions of immune effector cells against a variety of molds.

References

- 1.Richardson MD. Changing patterns and trends in systemic fungal infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005; 56:i5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh N Impact of current transplantation practices on the changing epidemiology of infections in transplant recipients. Lancet Infect Dis 2003; 3:156–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kontoyiannis DP, Bodey GP. Invasive aspergillosis in 2002: an update. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2002; 21:161–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappelletty D, Eiselstein-McKitrick K. The echinocandins. Pharmacotherapy 2007; 27:369–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfaller MA, Marco F, Messer SA, Jones RN. In vitro activity of two echinocandin derivatives, LY303366 and MK-0991 (L-743,792), against clinical isolates of Aspergillus, Fusarium, Rhizopus, and other filamentous fungi. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 1998; 30:251–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibrahim AS, Bowman JC, Avanessian V, et al. Caspofungin inhibits Rhizopus oryzae 1,3-β-D-glucan synthase, lowers burden in brain measured by quantitative PCR, and improves survival at a low but not a high dose during murine disseminated zygomycosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005; 49:721–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nivoix Y, Zamfir A, Lutun P, et al. Combination of caspofungin and an azole or an amphotericin B formulation in invasive fungal infections. J Infect 2006; 52:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Paetznick VL, Rodriguez J, Chen E, Kartsonis NA, Douglas C. Activity of caspofungin alone and in combination with amphotericin B lipid complex (ABLC) in a murine model of fusariosis (poster M-1841/482). In: Proceedings of the 47th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology, 2007:457. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahn JN, Hsu MJ, Racine F, Giacobbe R, Motyl M. Caspofungin susceptibility in Aspergillus and non-Aspergillus molds: inhibition of glucan synthase and reduction of [H9252]-D-1,3 glucan levels in culture. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006; 50:2214–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown GD. Dectin-1: a signalling non-TLR pattern-recognition receptor. Nat Rev Immunol 2006; 6:33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown GD, Gordon S. Immune recognition of fungal β-glucans. Cell Microbiol 2005; 7:471–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown GD, Gordon S. Immune recognition: a new receptor for [H9252]-glucans. Nature 2001; 413:36–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown GD, Herre J, Williams DL, Willment JA, Marshall AS, Gordon S. Dectin-1 mediates the biological effects of β-glucans. J Exp Med 2003; 197:1119–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romani L Immunity to fungal infections. Nat Rev Immunol 2004; 4:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wheeler RT, Fink GR. A drug-sensitive genetic network masks fungi from the immune system. PLoS Pathog 2006; 2:e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gersuk GM, Underhill DM, Zhu L, Marr KA. Dectin-1 and TLRs permit macrophages to distinguish between different Aspergillus fumigatus cellular states. J Immunol 2006; 176:3717–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hohl TM, Van Epps HL, Rivera A, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus triggers inflammatory responses by stage-specific[H9252]-glucan display. PLoS Pathog 2005; 1:e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shedletzky E, Unger C, Delmer DP. A microtitre-based fluorescence assay for (1,3)-[H9252]-glucan synthases. Anal Biochem 1997; 249:88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowman JC, Hicks PS, Kurtz MB, et al. The antifungal echinocandin caspofungin acetate kills growing cells of Aspergillus fumigatus in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002; 46:3001–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gil-Lamaignere C, Simitsopoulou M, Roilides E, Maloukou A, Winn RM, Walsh TJ. Interferon-[H9253] and granulocyte-macrophage colonystimulating factor augment the activity of polymorphonuclear leukocytes against medically important Zygomycetes. J Infect Dis 2005; 191: 1180–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meshulam T, Levitz SM, Christin L, Diamond RD. A simplified new assay for assessment of fungal cell damage with the tetrazolium dye, (2,3)-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulphenyl)-(2 H)-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT). J Infect Dis 1995; 172:1153–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bellocchio S, Moretti S, Perruccio K, et al. TLRs govern neutrophil activity in aspergillosis. J Immunol 2004; 173:7406–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denning DW. Echinocandin antifungal drugs. Lancet 2003; 362:1142–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angiolella L, Maras B, Stringaro AR, et al. Glucan-associated protein modulations and ultrastructural changes of the cell wall in Candida albicans treated with micafungin, a water-soluble, lipopeptide antimycotic. J Chemother 2005; 17:409–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hohl TM, Feldmesser M, Perlin DS, Pamer EG. Caspofungin modulates inflammatory responses to Aspergillus fumigatus through stage-specific effects on fungal β-glucan exposure [abstract 182]. In: Program and abstracts of the 45th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America Arlington, VA: Infectious Diseases Society of America, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi JH, Brummer E, Stevens DA. Combined action of micafungin, a new echinocandin, and human phagocytes for antifungal activity against Aspergillus fumigatus. Microbes Infect 2004; 6:383–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiller T, Farrokhshad K, Brummer E, Stevens DA. The interaction of human monocytes, monocyte-derived macrophages, and polymorphonuclear neutrophils with caspofungin (MK-0991), an echinocandin, for antifungal activity against Aspergillus fumigatus. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2001; 39:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishibashi K, Yoshida M, Nakabayashi I, et al. Role of anti-[H9252]-glucan antibody in host defense against fungi. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2005; 44:99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herre J, Willment JA, Gordon S, Brown GD. The role of Dectin-1 in antifungal immunity. Crit Rev Immunol 2004; 24:193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ha YS, Covert SF, Momany M. FsFKS1, the 1,3-[H9252]-glucan synthase from the caspofungin-resistant fungus Fusarium solani. Eukaryot Cell 2006; 5:1036–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steele C, Marrero L, Swain S, et al. Alveolar macrophage-mediated killing of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. muris involves molecular recognition by the Dectin-1 β-glucan receptor. J Exp Med 2003; 198:1677–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gantner BN, Simmons RM, Underhill DM. Dectin-1 mediates macrophage recognition of Candida albicans yeast but not filaments. EMBO J 2005; 24:1277–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Viriyakosol S, Fierer J, Brown GD, Kirkland TN. Innate immunity to the pathogenic fungus Coccidioides posadasii is dependent on Toll-like receptor 2 and Dectin-1. Infect Immun 2005; 73:1553–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bochud PY, Chien JW, Janer M, Marr KA, Aderem A, Boeckh M. Donor’s Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 haplotypes increase the incidence of invasive mold infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients [abstract B-1329] In: Program and abstracts of the 46th Interscience Congress on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology, 2006: 54. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sau K, Mambula SS, Latz E, Henneke P, Golenbock DT, Levitz SM. The antifungal drug amphotericin B promotes inflammatory cytokine release by a Toll-like receptor and CD14-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:37561–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis RE, Chamilos G, Prince RA, Kontoyiannis DP. Pretreatment with empty liposomes attenuates the immunopathology of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in corticosteroid-immunosuppressed mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007; 51:1078–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurtz MB, Heath IB, Marrinan J, Dreikorn S, Onishi J, Douglas C. Morphological effects of lipopeptides against Aspergillus fumigatus correlate with activities against (1,3)-[H9252]-D-glucan synthase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1994; 38:1480–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]