Abstract

Introduction: Informed consent for research biospecimen donations is traditionally obtained through a face-to-face interaction with research staff and by signing an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved printed form. Electronic signatures (eSign) are routinely used in the electronic medical record (EMR) for the consenting of clinical services after patients review printed documentation. Our goal was to develop an electronic self-consenting workflow that mimicked clinical services. Specifically, we tested a research consent process for the biobanking of remnant clinical samples that relies solely on clinical resources in a busy outpatient practice.

Materials and Methods: The Biorepositories Core Resource (BCR) unit initiated a new enterprise-wide biobanking infrastructure for consenting patients, termed Biospecimen Use for Research-Related Investigations and Translational Objectives (BURRITO). BURRITO is modeled after an established clinical process called Terms and Conditions of Service (TACOS). The TACOS requires patients to annually review printed documentation and self-consent electronically for clinical services. BURRITO also requires patients to review printed documentation and self-consent with eSign to opt-in for remnant biospecimen banking, but patients must complete this process only once. We captured eSign for consents directly into the EMR without research staff.

Results: Patients reviewed the IRB-approved documents and self-consented during their cardiology clinic visit. At checkout, their participation preferences were electronically documented by clinic staff. During a 6-month period, 123 patients agreed to donate. After a review of process, a second 3-month period identified 202 patients agreeing to donate. BURRITO did not require face-to-face interactions with research staff, used a “no-paper” eSign for consent, and created discrete fields in the clinical EMR of the patient's preference.

Conclusions: BURRITO electronically documents informed consent using an EMR functionality and the least amount of clinical and research resources. Our results show promise for developing institutionally adopted processes, which could leverage existing clinical workflows for universal research consenting and scalability.

Keywords: informed consent, quality improvement, electronic health records, biological specimen

Introduction

Human biospecimens are a critical resource for both clinical care and biomedical research. The use of human biospecimens in repositories serves to enhance prognostic clinical testing as well as to facilitate biological discovery through coordinated access to sample collections. Biospecimen research already has a track record of improving health care outcomes through analyses of large cohorts of biospecimens.1–4 Despite the many benefits for stakeholders, building and maintaining biorepositories is a complex enterprise.5 Research-oriented programs usually require individual resources that are independent (and sometimes outside) of clinical environments to obtain informed consent, protect patient data, and maintain physical and digital repositories of specimens.6–8

The School of Medicine at the UC Davis Health system (UCDH) and the Clinical and Translational Science Center established the Biorepositories Core Resource (BCR) to coordinate strategies and resources related to research-oriented biorepositories. A primary goal of this resource is to develop an enterprise-wide biobanking infrastructure that would meet broad consent regulations and enhance the utility of all stakeholders accessing available biospecimens.

Clinical tests usually produce a continuous source of remnant samples that are discarded after clinical performance but potentially could be used as research samples. Individual researchers in all schools and colleges interested in accessing these samples usually lack timely access to clinical biospecimens. Universal methodologies which could provide access to these samples for research (>15 million annually at UCDH) are in demand. To aid in this endeavor, the BCR initiated an enterprise-wide process for the collection of remnants of biospecimens.

In 2017, new rules were adopted by the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, or the “Common Rule.”9 These regulations promote uniformity, understanding, and compliance with human subject protections for participants who assume the risks of donation to advance a research enterprise. The new rules also intend to facilitate sustainable human biorepositories while protecting research subjects. Moreover, they want oversight not to add administrative burdens, particularly to low-risk research.

Traditionally, research consent for sample donations is captured and documented on study-specific paper-based forms. These forms are physically signed and referenced in patients' medical records. Recently, consent forms have become lengthier and more complex, which requires a face-to-face discussion between study-specific research staff and patients to ensure comprehension of the information. The final rule now expects forms to include a concise explanation of the key information most important to research subjects (i.e., the purpose of the research, the risks and benefits, and the appropriate alternatives that might be beneficial to prospective subjects) at the beginning of a lengthy consent form.

To comply with these new rules while expanding access to research biospecimens, we focused on developing an institutional methodology that simplifies the workflow process for obtaining informed consent documentation for remnant biobanking. We focused our efforts into efficiently capturing a subject's participation preference by leveraging the existing efficiencies of established clinical workflows that could be easily scalable to the institutional level. The developed new workflow mirrors clinical staff activities for obtaining clinical consent and captures a patient's donation preferences through a self-consent opt-in methodology that directly stores their preference into their electronic medical record (EMR) as discrete data fields. Self-consent allows a patient to review printed information on a study without a face-to-face presentation before signing consent. Our results demonstrate the scalable feasibility of integrating these multiple components in a new informed consent process.

Materials and Methods

The established clinical workflow at UCDH that routinely consents patients for clinical services is known as the Terms and Conditions of Service (TACOS). TACOS is a clinical form that requires patient review and a written electronic signature (eSign) annually. For internal project identification and in-service staff training purposes, our new remnant consent process is known within the university as the Biospecimen Use for Research-Related Investigations and Translational Objectives (BURRITO). This study and all materials were approved by both the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and clinic management, and follow the ethical standards on human experimentation in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

The BCR designed this study to test the feasibility of a new opt-in biospecimen consent process (i.e., BURRITO) in an outpatient clinic for remnant blood samples collected in the clinical laboratory. However, this process is not inherently limited to blood samples. Although approved by the IRB, collections of human remnant samples were not the focus of this study. We solely focused on testing the self-consent process and its integration into clinical workflows.

BURRITO components

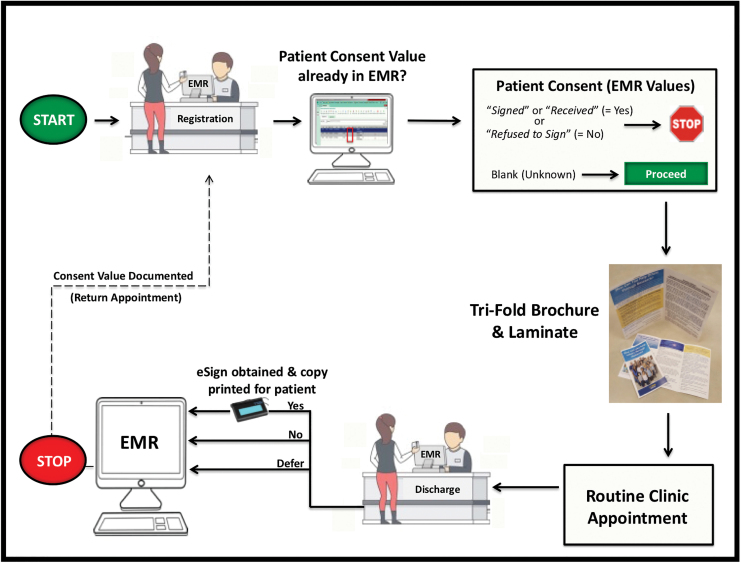

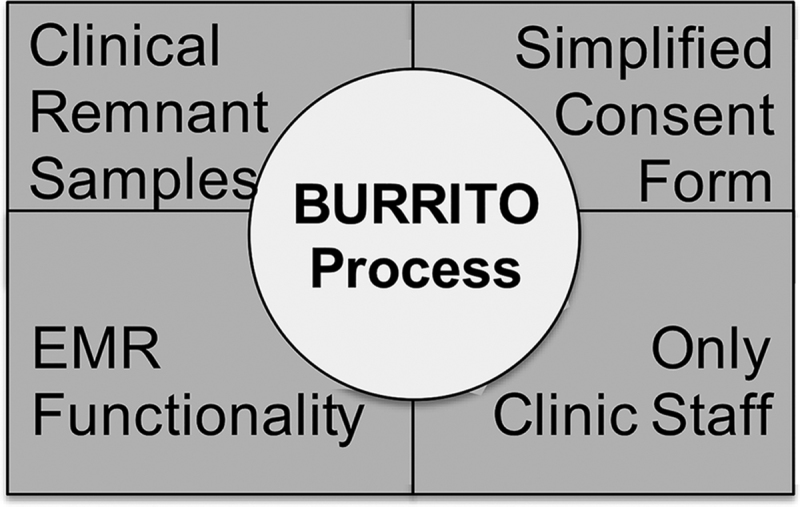

Four foundational components (Fig. 1) were deemed essential to the new BURRITO process (Fig. 2), and formed the basis for all subsequent workflows. These foundational components are:

FIG. 1.

Foundational components integrated by the BURRITO. BURRITO, Biospecimen Use for Research-Related Investigations and Translational Objectives.

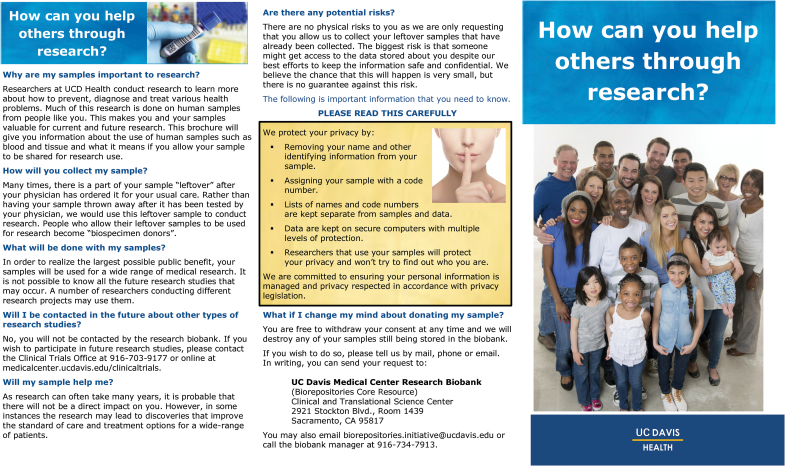

FIG. 2.

BURRITO consent process at UCDH Cardiology Clinic. The patient's consent is captured in the EMR as a Yes (“Signed” or “Received”), No (“Refused to Sign”), or blank (deferred a decision). When a patient arrives to clinic, they are offered consent materials to review if there is a “blank” in the EMR value column. EMR, electronic medical record; UCDH, UC Davis Health system. Color images are available online.

-

1.

Clinical remnant samples: The Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine (DOPLM) is accredited by the College of American Pathologists and has Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certification. The continuous source of CLIA procured and processed clinical samples, as well as the ability to leverage well-established DOPLM clinical resources (e.g., facilities, personnel, transport operations), led to remnant laboratory samples serving as our initial sample procurement target.

-

2.

Simplified consent documents: Three concise documents were designed as the required informed consent elements that must be provided to patients for self-consent. Using a minimal risk category associated with collection of clinical remnant samples, we obtained IRB approval for utilization of the following three simplified consent documents:

-

(i)

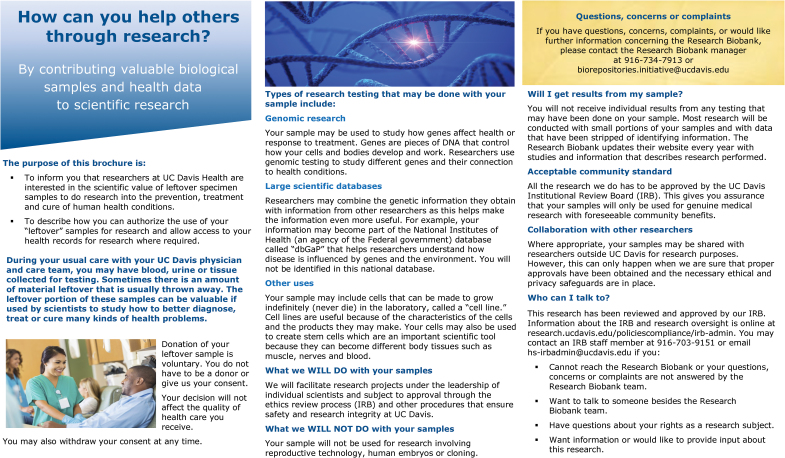

Tri-fold brochure: The tri-fold brochure introduces and describes the broader scope and purpose of the remnant biospecimen donation to the patient Fig. 3. It contains all appropriate elements of informed consent required by OHRP 45 CFR part 46.116(a), and it also meets internal Public Affairs branding policies.

-

(ii)

Consent form: The consent form is a one-page document that includes the six essential elements of information regarding remnant biospecimen donations usually required by IRBs. Presented in a bullet point format, the language of this form is easy to understand and contains the most critical information that may affect patients' willingness to donate. Additional important elements of informed consent (e.g., purpose and contact information) are also included on this page.

-

(iii)

HIPAA agreement: Collaborating with the Compliance office, the standard local HIPAA agreement (four pages) was condensed into a two-page document. This concise form allows the HIPAA agreement to be incorporated into a three-page laminated document along with the one-page consent form. Neither the consent form nor the HIPAA agreement in the laminate are signed by the patient but rather are used for informational purposes. This document remains located in each clinic room at all times (see workflow section below).

-

3.

Clinic staff workflow: The remnant biospecimen self-consent process was designed to be scalable at the institutional level, and not tied to research-specific staff availability or functions (e.g., research coordinators, biobank personnel, etc.). This new process was designed to mirror existing procedures routinely used in the clinic to electronically capture a patient's signature for TACOS. Tri-fold brochures were distributed by the clinic registration staff at check-in during a standard encounter, thereby allowing maximum time for the patient to review the materials during the visit. The three-page laminate was provided to the patient by clinic staff while in the clinic room. The patient typically has ample opportunity while waiting in the room before the physician encounter to review this information. At checkout, their donation preference was solicited by the clinic discharge staff.

-

4.

EMR clinical functionality: Two EMR clinic-based functionalities were critical to the success of the BURRITO process. These functionalities were routinely utilized by staff during the TACOS procedure and only required minor modifications to be used in the BURRITO process. These functions were enabled in the following steps:

-

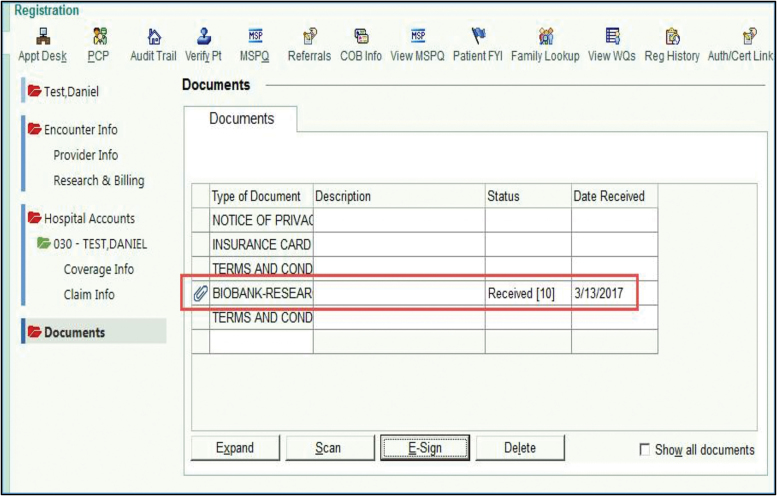

(i)

eSign Functionality: To capture the patient preference (consent), electronic patient signatures utilize the institutional EMR (Epic System Corporation, Madison, WI) clinical functionalities and adhere to the Uniform Electronic Transaction Act and Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce requirements for eSign verification.10 To capture patient signatures, the Topaz System, Inc. (Moorpark, CA) model T-LBK462-BSB-Re is employed through the health system. eSign data are stored as html files in the EMR. The patient must electronically sign twice; once for the consent form and the other for the HIPAA agreement.

-

(ii)

Preferences Stored as Discrete Data Fields: To store the patient's preferences directly in the EMR and to avoid traditional paper-only or portable document format (PDF) file formats, a discrete data field associated with each patient's record was created. There are only four values allowed in the clinical TACOS form field and each are associated with a time/date stamp field. These values are “Signed,” “Received,” “Refused to Sign” or no data are entered (i.e., blank). The “Signed” and “Received” values both reflect a patient that has viewed the TACOS clinical information and has agreed to electronically sign the form (the variation in terms is used for internal EMR purposes only). The “Refused to Sign” option represents a patient who has chosen not to sign the TACOS form before receiving services at UCDH. To minimize clinic staff training and to reduce EMR modifications, we utilized the same four TACOS clinical values to document patient consent for BURRITO. The final patient preference value is entered into the EMR at the checkout of an appointment. This entry serves as both the real-time source documentation and a quality control mechanism for the consent process.

FIG. 3.

Tri-fold brochure. Color images are available online.

Overview of adopted BURRITO workflow in cardiology clinic

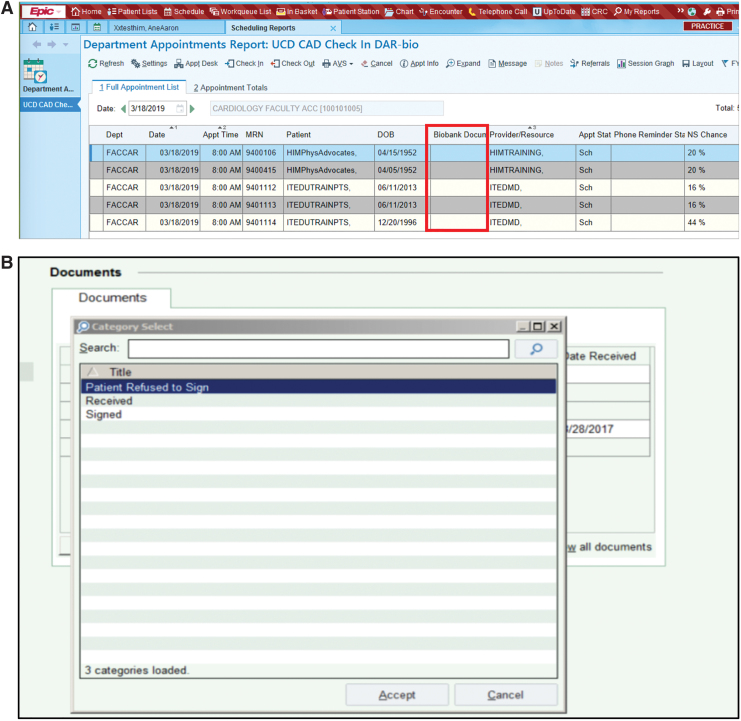

A schematic overview of the entire clinic encounter associated with the remnant biospecimen consent process is shown in Figure 2. Patients were first engaged at the registration counter when they arrived for their routine appointment in the cardiology clinic. The registration staff viewed their self-customizable Daily Appointment Reports (DAR), which indicate basic patient appointment information (e.g., time of appointment, physician, and purpose for visit). Working with clinical I.T., we created a new option field entitled “Biobank Document” that is viewable by registration staff on their DAR screens. This biobank document column contains the patient preference decisions to the remnant biospecimen donations. During an appointment, if the biobank document column contained patient preference decision data (i.e., “Signed,” “Received,” or “Patient Refused to Sign”), the registration staff would have no further BURRITO activities to perform as this indicates that a patient decision has already been captured (Fig. 4A, B). If the biobank document column remained empty (blank), the registration staff would provide the tri-fold brochure to patients and request that they review it while waiting in the clinic. Once in the clinic room, the registered nurse, licensed vocational nurse, or medical assistant provided the patient with the three-page laminate that contains the one-page consent form and two-page HIPAA agreement, and requested that they review it along with the tri-fold brochure already provided. The rooming staff also informed the patient that any decision concerning participation will be sought by clinic staff at checkout. All clinical staff were trained to answer basic questions concerning the consent process but did not provide informed consent to the patients.

FIG. 4.

Patient consent choices (options) are recorded as an EMR value. (A) Biobank Document (BURRITO) preference value is available in the EMR DAR (same value options as TACOS) for selection. The DAR is customized in the EMR to view the Biobank Document column next to PHI. (B) Shows values of Received, Refused to Sign, or unknown in the data field where they are selected. DAR, Daily Appointment Reports; TACOS, Terms and Conditions of Service. Color images are available online.

Similar to the registration staff, the discharge staff reviewed the DAR screen to determine if the patient already had documented a remnant donation preference in the EMR. If a documented decision was in the biobank document column, the discharge staff had no further BURRITO-related activities to perform. If the document column was blank, the discharge staff inquired whether the patient had an interest in remnant biospecimen donation. If the patient agreed to participate, the discharge staff completed the EMR eSign process described above by selecting either “Signed” or “Received” in the dropdown list of data value options (Fig. 4B). The EMR data from the patient's eSign are displayed in Figure 5. If the patient reviewed the materials and did not agree to remnant biospecimen donation, the discharge staff would select the “Refused to Sign” dropdown data value and indicate that no eSigns were sought. If the patient requested additional time before making a preference decision, had questions concerning the distributed documents, or wanted more information about the research donation, they were provided the contact information (i.e., phone number and e-mail) to the BCR coordinator for questions or concerns.

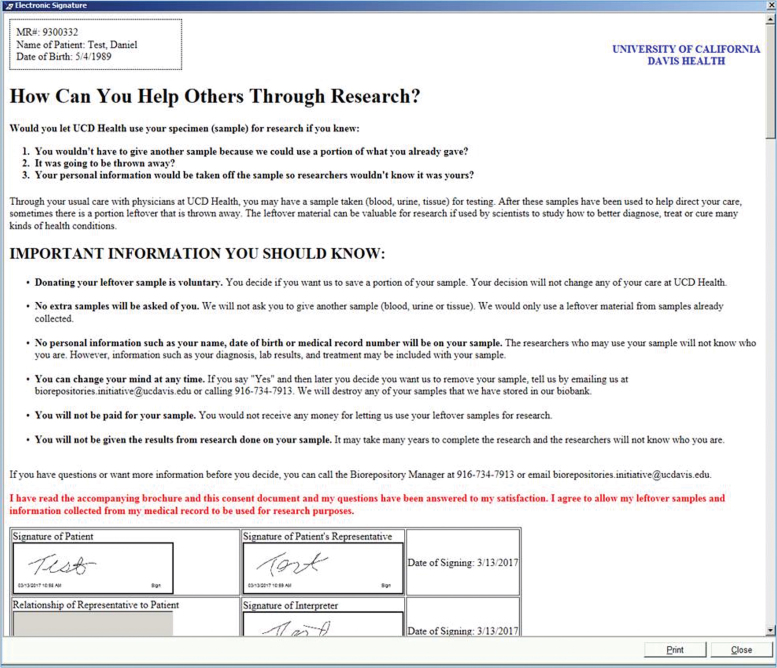

FIG. 5.

eSign view through the Topaz system. Patients are required to use this system for multiple eSign (clinical or research). Therefore, clinic staff must designate which EMR signature block is appropriate for the BURRITO signature (e.g., Patient, Patient Representative, Interpreter). Once signed, a print option of the signed consent document is available. eSign, electronic signatures. Color images are available online.

At any time, a patient may rescind or revoke their consent. When this request is received, clinic staff documents the revocation of consent by modifying the discrete Biobank document field from either “Signed” or “Received” to “Refused to Sign,” indicating the patient's change in preference. The audit trail of this change in the EMR data field contains the date, time, and name of authorized UCD staff member who performed the change, as well as previous values. The revocation can be viewed by hospital staff throughout the institution regardless of hospital or clinic location in real-time. In addition, the modified value is utilized in real time through query to determine if patient authorization has been provided before procurement of remnant samples by the DOPLM.

Results

This study included two testing phases (I and II) of a new consent process (i.e., BURRITO) occurring during routine outpatient visits to our cardiology clinic. Figure 1 depicts the four foundational components that were incorporated in this new BURRITO methodology. The process was designed and implemented in consultation with the clinical managers, nursing staff, clinicians, and registration staff from the time of inception. For this process to be sustainable across the many clinics of our large health care system, we opted to utilize exclusively clinical staff instead of research personnel to capture informed consent. We involved clinical staff early in the development phase to both acclimatize, understand, and model existing clinical workflows and dependencies in the research process. Mirroring the standard TACOS clinical process, our phase I approach utilized clinical staff as the facilitators in integrating our simplified consent forms and EMR functionality into the daily workflow of the clinic. We avoided any additional clinical staff duties that would impede the adoption of the workflow or consume more time with patients through their clinic encounters.

In phase I, we first monitored 25 half-day clinics that were attended by engaged, trained, and supportive cardiology faculty champions. Phase I took ∼6 months to complete with 123 patients agreeing to donation (∼5 patients per week). Although we received an overall positive verbal response to the process from patients in an informal exit survey, the rate of consent varied from 4% to 90% from day to day. Two predominant factors were identified to account for this variability: (1) variable levels of staff knowledge of the process, and (2) a lack of an EMR-based way to identify a patient's preference. Clinical staffing is variable as many individuals can provide the same services across many different clinics. Hence, having part-time and transitory personnel with different levels of exposure and understanding about the BURRITO process created a variable performance during the initial months. As time went by and more part-time and transitory staff gained experience and memory of the process, this variation became less of an issue.

After phase I, we used two small group discussions to assess our progress with invested staff in the clinic. They highlighted that not having an EMR-based tool to track a patient's preference in real-time was a barrier for consistency in our process. They recommended creating a new discrete field entitled “Biobank Document” that is viewable by registration staff on their DAR screens. This modification consisted of establishing a patient preference data column within the self-customizable EMR DAR screens (Fig. 4A). This simplified visualization of patient preferences during the registration and discharge workflows was requested by the staff themselves to maximize efficiency. A single 1-hour retraining session with all staff before initiation of phase II was then conducted to address peer training and the searchable EMR utility of those patients that have already expressed their consent preference. Other than reinforcing the process with the staff and answering questions, the training focused on how to apply this EMR technical modification. Using this modified protocol for phase II over a 3-month period, we obtained consent for donation from 202 patients (∼17 patients per week). These changes increased the rate of patients agreeing to donate in a shorter time period while using the same clinic setting and level of resources.

During phase I and II of testing, a total of 325 patients agreed (30% success rate) to having their clinical remnant samples donated for research. No one rescinded their consent during the study. Consents were obtained solely by clinical staff without use of a traditional face-to-face informed consent encounter by research staff. A retrospective count of physician-ordered clinical blood tests (e.g., Complete Blood Count, Chemistry panels, or Troponin level) was performed for these 325 patients over a 12-month observation period. This count showed that the DOPLM processed 1914 separate blood samples from these patients during this period. This estimate provides an indication of potential quantities of remnant samples that could feasibly be made available for research studies within months of a BURRITO-based research protocol initiation.

Discussion

UCDH already has an established workflow (i.e., TACOS) for patients to self-consent for clinical services. The consent signature is electronically recorded in a discrete EMR field in real time by the clinic staff during routine visits. This allows yearly consenting to health services at any registration site. The main finding of this study is that minimal modifications of these already-established clinical processes can effectively be integrated to obtain a one-time “opt-in” self-consent for biobanking of remnant clinical biospecimens that is applicable anywhere in the health system. Our IRB-approved consent process utilizes the least amount of clinical and research resources that we can identify in the literature. Furthermore, it yielded a comparable level of patient agreement to other self-consent biobanks utilizing clinical resources without the development of new research infrastructure outside of adding a single clinical EMR data capture function. Early involvement and retraining of clinical staff enhanced the efficiency of this process and prevented the use of research staff in the consent process, as done in many other large biobanks.6,11,12

Future widespread use of fully integrated self-consent processes that model local clinical workflows, like in the BURRITO process, has the potential to scale up and consent large numbers of research patients in short periods of time and with minimal resources. Furthermore, incorporating the patient's preference for biobanking into discrete EMR data fields provides full disclosure of a patient's consent (i.e., either a yes or no for biospecimen collection) across the entire health system in real time. We believe that the system-wide implementation of this new BURRITO process will provide an efficient “opt-in” option for broad consent strategies (i.e., remnant sample collection, re-contact registries) that provides full disclosure of a patient's preference in real time.

Scalable infrastructure

Large-scale procurement of biospecimens for research purposes remains challenging.5 Sometimes these challenges are partly due to a lack of connection between traditional clinical processes and resource-intensive efforts in the research space.13 Frequently, biorepositories have to develop independent infrastructures for patient consenting and/or sample collections outside of the clinical space. Requiring additional research infrastructure and resources can strain the long-term sustainability of large-scale biorepositories and inhibit the generalization across institutions.7,14 One way to address this long-term sustainability challenge is to leverage the traditional clinical infrastructure for patient consenting to serve the dual purpose of research consenting.11,15 This approach is appealing because it would lower the investment in research processes and prevents replicative workflows in separate spaces (i.e., clinical vs. research).

Biobanking consents are usually performed through an “opt-in” process (∼80% of the time), where patients are asked if they want to participate in biobanking.16 While “opt-out” may sound less involved as an alternative method, designing and implementing either strategy can limit widespread use of biobanking.14,15 Our study focused on leveraging a standardized institution-wide clinical consenting process (i.e., TACOS) as a model for obtaining research self-consent for remnant biospecimen collections in our outpatient cardiology clinic (i.e., BURRITO). Our success rate was comparable to the report by Saben et al.,11 where they included biobanking consents into the clinical registration process of the emergency department. One important difference between our processes is that they had their registrars trained on how to consent patients, and research staff provided support during consenting. The BURRITO process is unique because it does not depend on registrars or research staff to participate during the informed consent process. This suggests that this additional training and research staffing is not required for successful consenting. Our results demonstrated the ease of integrating a true self-consent research process and core EMR functionality into the clinical space that follow established clinical process. By learning from clinical workflows already in place and avoiding replicative research efforts, we minimized the burden on new research resources (i.e., no new staff was needed for consenting patients) and limited the burden placed on clinical programs (i.e., only one additional EMR step was added during a patient's attendance to the clinic). Hence, the resources needed for implementation of this process were minimal and likely very sustainable into the future as long as the clinical staff is retrained over time to sustain the effort.

Value to involving clinical personnel

The components of BURRITO mirrored existing clinical registration and discharge workflows and maximized utilization of clinical staff while alleviating the need for research personnel (i.e., coordinators, nurses, biobank technicians) in the clinic. Because of the minimal risk category associated with the collection of clinical remnant samples and their deidentification before distribution to researchers, we obtained IRB approval to alleviate the traditional need for a face-to-face consent process. By soliciting staff engagement in phase I and redesigning phase II, we met the expectations of the clinical staff and allowed them to participate in designing functionality while also minimizing additional clinical effort. We experienced constructive support from both the front-line clinic staff and the clinic management, which greatly facilitated implementation, design, and development throughout both phases of BURRITO.

Utilizing clinical staff also reduced the costs associated with training. The clinical enterprise is usually responsible for ensuring compliance training to clinic staff on how to document patient preferences in the EMR. When updates to the documentation process are enacted, the clinic staff are quickly trained on how to apply these to their standard practices. For this new research workflow, our BCR has assumed the responsibility of monitoring these changes and updating the research workflows so that they continue to mirror clinical updates. This approach reduces the need to train the clinical staff on different research processes that can be cumbersome or in conflict with clinical practice. Lastly, using discharge staff (i.e., nonclinical) to solicit and capture patient consent preferences minimizes potential coercion or undue influence by clinical staff during the routine clinic visit. Altogether, these features support the ability of BURRITO to organically evolve with the clinical space over time and with upgrades to sustain a large-scale effort to recruit patients for biomedical research.

Value to utilizing the EMR

Traditionally, when the EMR has been used to document consent, the forms are stored as scanned PDF files. The PDF file is then manually uploaded to the EMR by various medical records personnel. While a patient's signed consent may be stored as a PDF in the EMR, this format is not conducive to downstream data exchange, utilization within sub-EMR modules (e.g., laboratory information management systems), or in notifying the patient consent status to internal resources. This traditional paper-based consent approach is labor intensive when applied to the broad consent processes because it requires a human interface to verify the correct completion of the forms. Moreover, it is difficult to leverage paper-based consents as a source of record for downstream data interoperability.17 In BURRITO, a patient's preference is stored as discrete data fields, which adds downstream functionality and efficiency. For example, at a patient's request, their preferences can be modified within the source documentation in the EMR by any registrars through a telephone call or an in-person request at a time other than their original clinic visit. Under the current BURRITO process, however, a new opt-in preference would require a physical signature in the Topaz system.

One additional benefit to documentation of consent and updates in the EMR is the generation of time-stamped audit trails (Fig. 6). Storing these preferences as a discrete data value in the EMR clinical environment also allow institutional-wide viewability for data sharing among clinics as well as submodules or peripheral applications (e.g., central laboratory vs. satellite laboratories verification). The use of the eSign clinical functionality to capture patient eSign also obviates the need for hard-copy, paper-based consent documentation being generated, copied, scanned, or uploaded to EMR, thus saving time and effort of both research and medical records personnel. In 2014, Simon et al.18 reported that less than 10% of surveyed biobanks (n = 65) were using eSign, and 100% were still using traditional consenting methods. Our study effectively combines an opt-in self-consent workflow that uses eSign and tracks in real-time a patient's preference throughout the entire health system.

FIG. 6.

An audit trail is automatically generated to capture patient eSign in the EMR. Color images are available online.

Furthermore, our approach provides the ability to electronically document in the EMR a patient's option to not participate (“Refused to Sign”) in real time. Documenting nonparticipation in the EMR so that it is viewable by multiple UCDH stakeholders serves several purposes: (1) it alleviates the potential for repeated requests to donate if patients have multiple appointments at various clinic locations, (2) it allows the clinical laboratory to electronically query for a patient's preference about donating remnant samples for research before deidentification of samples, (3) it takes a proactive approach to tracking patients' wishes, following appropriate regulations, and avoiding the inadvertent use of samples from patients that have clearly expressed a desire to opt-out, and (4) it provides a recorded and dated opt-out decision that facilitates complying with patients preferences as per the new common rule before an IRB granting a consent waiver. It also provides the ability to rescind the consent at any time and at any place of registration in the institution at the request of the patient. During this study period we had no request to withdraw consent. Hence, this process lends itself to expanding the abilities of the institution to respect a patient's wishes without increasing a burden in process and regulations.

Future ethical considerations

Although the Final Rule published January 19, 201819 did not require institutions to develop a tracking mechanism to honor patient requests who refuse broad consent for secondary research, the BCR leadership, in considering future potential ethical concerns, decided to proactively document the opt-in or opt-out wishes of a patient in the EMR for remnant samples as a way to facilitate changes in future regulation, patient's requests, and changes in biobanking models.5 Furthermore, the use of EMR-based tracking of patient consent continues to strengthen the informatic separation between investigators and repository programs implied in the concept of secondary use of human biospecimens and patient confidentiality.

Limitations

One limitation of our study is that although we sought to determine the patients' understanding of the consent, we mostly learned about the process. Our clinical champion (a cardiologist) asked if patients had questions about the materials at the end of the clinical encounters during phase I. Most of the questions were about how and where to sign up. Retraining the staff to volunteer this information upfront during phase II eliminated these questions. We assumed that if patients had more questions about the process or did not understand the material content, they would not consent, or they would defer to a next visit or contact the BCR coordinator listed in the documents. We received five calls with questions during the study period (<1% of patients engaged by the process). Since no staff were consenting the patients just recording their decisions, we do not know the reason why patients did not agree to consent or deferred making a choice. Although BURRITO is a preferred method from a clinical, research, and a resource management point of view, we think that future studies could further assess the patients' factors influencing consent and/or alternative ways of enhancing self-consenting while providing all necessary information.

Conclusion

We have shown that minimal modifications of already-established clinical processes can effectively be used for research self-consenting. This approach to consenting and EMR-based electronic documentation offer an opportunity to implement this powerful resource on a broader scale with the consumption of minimal resources for patient-centered development of human biorepositories.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Matthew Hwang for his data compiling contributions for the pilot studies; Beverly J. Schacherbauer and Deanna L. Norwood for their contributions coordinating the staff and implementing new process in clinic; the clinical staff at the Cardiology Clinic for their eagerness and professionalism while developing these methods; and Sophie A. López for her grammatical review of the article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This study was supported by the UCDH Clinical and Translational Science Center grant UL1TR001860 and the KL2 scholar program supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; NIH UL1 TR000002 (to JEL).

References

- 1. Womack C, Mager SR. Human biological sample biobanking to support tissue biomarkers in pharmaceutical research and development. Methods 2014;70:3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Castillo-Pelayo T, Babinszky S, LeBlanc J, Watson PH. The importance of biobanking in cancer research. Biopreserv Biobank 2015;13:172–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sarojini S. Proactive biobanking to improve research and health care. J Tissue Sci Eng 2012;03:1–6 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kinkorova J. Biobanks in the era of personalized medicine: Objectives, challenges, and innovation: Overview. EPMA J 2015;7:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Allen D. A failed model. Pathologist 2017;817 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ost JA, Newton PW, Neilson DR, Cioffi JA, Wackym PA, Perkins RS. Progressive consent and specimen accrual models to address sustainability: A decade's experience at an oregon biorepository. Biopreserv Biobank 2017;15:3–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. De Souza YG. Sustainability of biobanks in the future. Adv Exp Med Biol 2015;864:29–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carpenter JE, Clarke CL. Biobanking sustainability—Experiences of the Australian Breast Cancer Tissue Bank (ABCTB). Biopreserv Biobank 2014;12:395–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Menikoff J, Kaneshiro J, Pritchard I. The common rule, updated. N Engl J Med 2017;376:613–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act. Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-106publ229/pdf/PLAW-106publ229.pdf (accessed December18, 2019)

- 11. Saben JL, Shelton SK, Hopkinson AJ, et al. The emergency medicine specimen bank: An innovative approach to biobanking in acute care. Acad Emerg Med 2019;26:639–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Akervall J, Pruetz BL, Geddes TJ, Larson D, Felten DJ, Wilson GD. Beaumont health system biobank: A multidisciplinary biorepository and translational research facility. Biopreserv Biobank 2013;11:221–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paradiso A, Hansson M. Finding ways to improve the use of biobanks. Nat Med 2013;19:815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pulley J, Clayton E, Bernard GR, Roden DM, Masys DR. Principles of human subjects protections applied in an opt-out, de-identified biobank. Clin Transl Sci 2010;3:42–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roden DM, Pulley JM, Basford MA, et al. Development of a large-scale de-identified DNA biobank to enable personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008;84:362–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edwards T, Cadigan RJ, Evans JP, Henderson GE. Biobanks containing clinical specimens: Defining characteristics, policies, and practices. Clin Biochem 2014;47:245–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Strech D, Bein S, Brumhard M, et al. A template for broad consent in biobank research. Results and explanation of an evidence and consensus-based development process. Eur J Med Genet 2016;59:295–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Simon CM, Klein DW, Schartz HA. Traditional and electronic informed consent for biobanking: A survey of U.S. biobanks. Biopreserv Biobank 2014;12:423–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects; Final Rule Federal Register. Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-06-19/pdf/2018-13187.pdf (accessed December18, 2019) [PubMed]