Abstract

Women remain underrepresented in HIV research. The AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) 5366 study was the first HIV cure-related trial conducted exclusively in women. Our multidisciplinary team integrated participant-centered reports into the ACTG 5366 protocol to elicit their perspectives. We nested mixed-methods surveys at the enrollment and final study visits to assess ACTG 5366 participants' perceptions and experiences. Of 31 participants enrolled in the ACTG 5366, 29 study agreed to complete the entry questionnaire and 27 completed the exit survey. The majority of study participants were nonwhite. We identified societal and personal motivators for participation, understanding of risks and benefits, and minor misconceptions among some trial participants. Stigma was pervasive for several women who joined the study, and served as a motivator for study participation. Reimbursements to defray costs of study participation were reported to facilitate involvement in the trial by about one-third of participants. Almost all respondents reported positive experiences participating in the ACTG 5366 trial. The ACTG 5366 study showed that it is possible to recruit and retain women in HIV cure-related research and to embed participant-centered outcomes at strategic time points during the study. The findings could help in the design, implementation, recruitment, and retention of women in HIV cure-related research and highlight the value of assessing psychosocial factors in HIV cure-related research participation.

Keywords: women living with HIV, HIV cure-related research, vorinostat, taxomifen, social sciences, behavioral sciences

Introduction

Despite bearing a significant burden of the HIV epidemic,1,2 women remain chronically underrepresented in HIV research.3,4 In a landscape analysis of HIV cure-related research, women accounted for 17.3% of participants in human trials conducted through 2017.5 A systematic review of 104 HIV cure-related studies published between 1995 and 2012 showed that women represented a median of 11.1% participants in these studies.3 In a second review of 151 publications on HIV cure-related clinical studies between 1995 and 2003, only 6% disaggregated analyses by sex/gender variables.6 The low representation of women is concerning in light of data suggesting important differences in immunologic and virologic factors between women and men.7–12

Sex differences have been demonstrated in viral reservoir dynamics10 and sex hormones appear to mediate mechanisms of latency maintenance and reversal.13 In addition to biological differences, sociobehavioral factors (e.g., access to care, adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), stigma, disempowerment, and marginalization) affect clinical outcomes.6 Understanding how these biological and sociobehavioral differences affect HIV cure-related research efforts will be critical in ensuring that interventions are safe and effective in both women and men.

The AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) 5366 study (“Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators to Enhance the Efficacy of Viral Reactivation with Histone Deacetylate Inhibitors”) [NCT03382834] was the first HIV cure-related trial conducted exclusively in women.14 This randomized, open-label latency-reversal trial assessed the effects of tamoxifen exposure in combination with vorinostat, compared to vorinostat alone, on viral reactivation among postmenopausal cisgender women living with HIV who were virally suppressed on ART in the United States. The trial enrolled 31 women living with HIV (21 in the tamoxifen + vorinostat arm, and 10 in the vorinostat alone arm).

Furthermore, very few data exist regarding participant experiences within HIV cure trials. We and others have advocated for strategically embedding assessments of participant experiences into ongoing HIV cure trials to improve recruitment, informed consent, and retention of study participants.15–17 While such work is emerging,18,19 to date, few trials have included participant reports in the United States,20 and none has focused on women. With a multidisciplinary team of sociobehavioral scientists, HIV patient advocates and community members, bioethicists, biomedical HIV cure researchers, HIV care providers, and psychologists, we integrated participant-centered reports into the ACTG 5366 protocol to elicit motivations, perceptions, and experiences of women in the trial. The main objective of the social sciences component of the ACTG 5366 protocol was to determine how women enrolled in the study perceived and experienced the trial. In this study, we report data from surveys administered at study enrollment and exit. To ensure proper de-identification of the participant who completed responses in Spanish, her results are presented in English.

Methods

Nested, mixed-methods surveys assessing ACTG 5366 participants' perceptions and experiences were administered at the enrollment visit and at the final study visit. The enrollment visit took place ∼1 month after screening evaluations and coincided with the start of protocol interventions (i.e., vorinostat ± tamoxifen). The exit survey took place around 65 days after study entry. Surveys were administered online using Qualtrics (Provo, UT) from June to December 2018. Participants were given the option to decline survey completion. In exchange for their time, participants received $25 for entry survey completion and $15 for exit survey completion, in addition to receiving compensation for their time related to participation in the clinical portion of the trial according to the Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved informed consent form and local clinical research site (CRS) procedures. The study was conducted at 15 US-based CRS in the ACTG network and all participating sites received standardized survey administration training before study initiation.

Survey items were developed in collaboration with the community representatives (K.S. and D.E.), and the ACTG 5366 study protocol specialist (L.H.), along with input from the ACTG 5366 protocol team. Surveys were translated by a professional Spanish translator without back-translation to English. Women with limited literacy were offered assistance in reading and recording responses. The study was approved by the IRB from each participating CRS and separately approved by the UNC Non-Biomedical IRB.

The entry survey covered the following domains: demographic and self-perceived health status characteristics, attitudes toward HIV cure-related research, motivations driving decisions to participate in the ACTG 5366 study, scientific understanding of the study, perceptions of risks and benefits, meaning of study participation, role of self-image and stigma, and role of study compensation. The exit survey covered overall experience in the study, decisional regrets, and recommendations to improve the study and future similar studies. Response options included yes/no/don't know, true/false, multiple choice, and slide-bar questions. Surveys also contained “specify” and “please explain” questions, as well as open-ended free-text questions intended to solicit short responses. We pilot tested the ACTG 5366 social sciences surveys in collaboration with participating CRS and the community representatives (K.S. and D.E.), and made revisions to the instruments before study start. We did not conduct formal cognitive testing.

We chose a convergent mixed-method design and gave equal weight to both quantitative and qualitative responses.21 Given the small sample size, we analyzed quantitative data descriptively, providing frequencies of responses aggregated across all ACTG 5366 sites without bivariate or multivariate analyses. Due to the sensitive nature of the data and the small enrollment, site-specific data are not reported. For semistructured and open-ended questions, we conducted conventional content analysis to systematically organize text units into a structured format. We did not use a preexisting coding scheme. Due to the small number of responses and brevity of text units, the lead author organized emergent themes in a Microsoft Word processing document. For each question, similar responses were clustered into key themes. A research assistant reviewed the participants' responses and confirmed the themes that initially emerged. Here, we provide quotations that were broadly representative of the key themes that transpired in the survey responses. We first report results from the enrollment surveys, followed by those of the exit surveys.

Results

Entry surveys

Demographic and health characteristics of respondents

Of the 31 women enrolled in the ACTG 5366 study, 29 (93.5%) agreed to complete the entry survey (28 in English and 1 in Spanish). Of those who completed the entry survey, 18 were black/African American, 10 were white, and 1 was American Indian/Alaskan Native. Seven had less than high school education, and 18 had a yearly household income of less than $25,000, 14 relied on some form of government support to cover basic living and other expenses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of AIDS Clinical Trials Group 5366 Female Respondents at Entry Visit (n = 29)

| Demographic characteristicsa | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| Black or African American | 18 (62.1) |

| White | 10 (34.5) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (3.4) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latina | 25 (86.2) |

| Not Hispanic or Latina | 4 (13.8) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 7 (24.1) |

| High school or general education development/diploma | 4 (13.8) |

| Some college (less than 2 years) | 8 (27.6) |

| Associate degree or more than 2 years of college | 5 (17.2) |

| Undergraduate degree or equivalent | 4 (13.8) |

| Professional degree (e.g., Master's degree or equivalent) | 1 (3.4) |

| Doctorate degree or equivalent terminal degree | 0 (0) |

| Current marital status | |

| Single, never married | 7 (24.1) |

| Married, without children | 1 (3.4) |

| Married, with children | 5 (17.2) |

| Divorced | 6 (20.7) |

| Separated | 3 (10.3) |

| Widowed | 6 (20.7) |

| Did not answer | 1 (3.4) |

| Yearly household income (in US dollars) | |

| Less than $25,000 | 18 (62.1) |

| $25,000–$50,000 | 7 (24.1) |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 1 (3.4) |

| $75,001–$100,000 | 2 (6.9) |

| More than $100,000 | 1 (3.4) |

| Sources of money or support to cover basic living and other expensesb | |

| Regular, full-time job | 7 (18.9) |

| Regular, part-time job | 5 (13.5) |

| Temporary work | 1 (2.7) |

| Help from family, partners or friends | 5 (13.5) |

| Some form of government support | 14 (37.8) |

| Otherc | 3 (8.1) |

| Refuse to answer | 2 (5.4) |

Demographic data for exit survey completers not shown.

Categories are not mutually exclusive, so percentages add up to more than 100%.

“Other” included three respondents with Social Security Income or work pension.

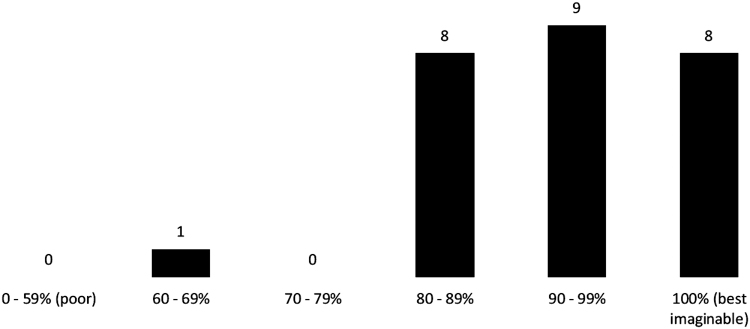

We asked ACTG 5366 study participants to assess their own health status at the entry visit using a scale of 0% (poor) to 100% (best imaginable). Of the 26 women who answered this question, only one scored below 80%, and all others reported a score >80% denoting self-perceived good health (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Self-assessment of current health status at entry visit (n = 26).

Attitudes toward HIV cure research at study entry

Meaning of an HIV cure

At the entry visit, ACTG 5366 study participants were asked to describe what an HIV cure would mean to them. Of the 29 respondents, 8 stated that HIV cure would mean not having to take HIV medications (e.g., “my life with no meds,” “no longer have to take any medications for HIV,” “never taking medicine”). Furthermore, six women equated a cure with freedom, hope, empowerment, life, and living without fear (e.g., “it means liberation from HIV stigma and a revolution of medical proportion,” “it means hope to be cured from this virus,” “hope for HIV patients,” “life”), and five referenced having HIV completely eliminated from the body. Additional responses included “better immune system,” “that I would be healthier,” “so that I don't have to go to the doctor all the time,” among others.

Meaning of HIV cure-related research and experience with research participation

When asked to describe what HIV cure-related research meant to them, nine women indicated that research meant getting closer to the possibility of cure (e.g., “means we are getting closer to a real cure,” “it means that they [researchers] will find a cure [for] people that are living with the virus through research”). Eight stated that HIV cure-related research meant helping other people living with HIV, including dealing with stigma (e.g., “finding a cure to help people not to be stigmatized,” “helping others not having to live with a disease that is so stigmatized by society,” “to help others, to help future generations”). Two made reference to improvements in HIV therapeutics, and other respondents saw the opportunity to be able to make a difference.

In terms of previous participation in research, 22/29 women were new to HIV cure-related research participation, 5/29 had prior HIV cure-related research experience, and 2/29 did not know if they had previously participated in an HIV cure-related study. Only about half (15/29) of the women had previously participated in an HIV-treatment study, including other ACTG HIV observational and treatment studies. All women (29/29) indicated general interest in HIV cure-related research.

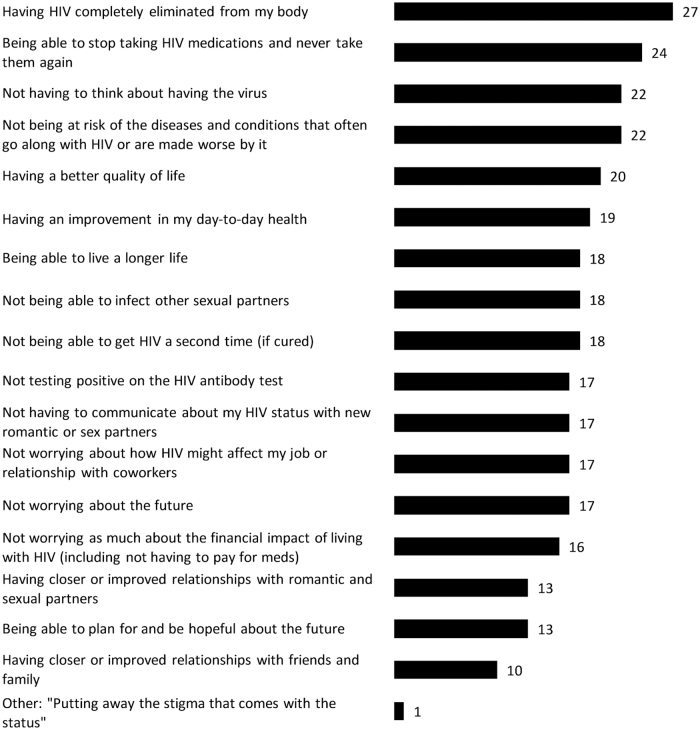

Greatest potential benefits

In terms of the possible benefits of a future HIV cure/remission strategy that would most positively affect the lives of ACTG 5366 study participants, the five most frequent answers were the following: (1) having HIV completely eliminated from the body (27/29), (2) being able to stop taking HIV medications permanently (24/29), (3) not having to think about having the virus (22/29), (4) not being at risk of the diseases and conditions that often go along with HIV or are worsened by it (22/29), and (5) having a better quality of life (20/29) (Fig. 2). One woman wrote that “putting away the stigma that comes with the status” would most positively affect her life.

FIG. 2.

Attributes of a possible future HIV cure/remission that would most positively affect lives of ACTG 5366 female participants (n = 29). ACTG, AIDS Clinical Trials Group.

Motivators of participation in ACTG 5366

Primary reason for enrollment

Participants were asked for the primary reason they decided to participate in the study at the entry visit. Over two-thirds (21/29) wrote an answer related to altruism or helping find a cure for HIV. Representative quotes included: “the primary reason I decided to participate in this study is to help see if certain medicines will help researchers with a cure for the disease,” “to serve as a participant and to enable the process towards finding a cure that will help others be liberated from this deadly virus,” “I decided because I want to be an example for other people that [who] are living with [this] virus that there is research and medicine out there that can help them get better,” “to help provide data to further cure,” “helping science and contributing to studies,” and “to help my community.” Interestingly, 2/29 women wrote about their desire to be cured of HIV (e.g., “to be cured” and “because I wanted a cure”). Additional responses related to hope for cure, medical care, and ensuring representation of women in research (e.g., “to hope for a cure,” “because they [researchers] care more about my health” and “not enough women to do them [studies]”). With respect to decision-making around enrollment, most (23/29) women discussed their participation with at least one other person, including HIV care provider or HIV care team and family members.

Satisfaction with informed consent

All but one participant indicated that they were satisfied with the informed consent process. When asked to specify why they were satisfied with the informed consent process, respondents wrote: “the study and the consent were explained so that I understood,” “because the consent is very thorough so I can understand the study,” “[the] doctor explained [the] study thoroughly and that made me feel that I was not in danger,” “the information appears to have a clear plan to cure the virus,” and “the nurse was very specific.”

Understanding of the ACTG 5366 Study

Main purpose of study

At the entry visit, we asked ACTG 5366 participants to describe the main purpose of the study using free text responses. (The study purpose was described as follows in the ACTG 5366 informed consent form: “Researchers will study whether these two medications [vorinostat and tamoxifen] given together are safe and tolerable. Researchers will also look at whether the two drugs work better together in waking up the latent virus in women than vorinostat given alone.”) Over two-thirds (22/30) of participants described the study as helping advance HIV cure-related science. Some participants had a rather sophisticated understanding of the study. For example: “to see if estrogen receptor can awaken the latent virus in the reservoirs allowing medications to act on stopping its replication,” “to find out if a) latent cells can be woken up and b) if one drug can work equally well as two drugs,” and “[t]o help researchers find a cure to HIV by connecting or combining two medications and seeing their response together in clearing the virus.” A minority (4/29) of participants described ACTG 5366 as searching for positive results leading to a better treatment or cure for HIV.

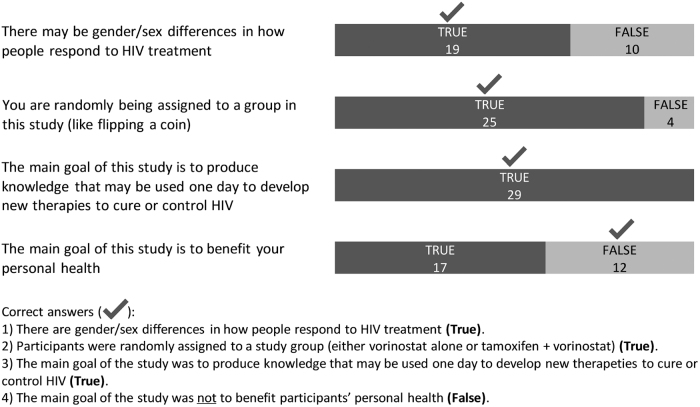

Four true/false questions were used to clarify study understanding (Fig. 3). All women (29/29) correctly understood that the study produced knowledge that may be used one day to develop new therapies to cure or control HIV. The majority (25/29) accurately recognized that they were being randomly assigned to a study group. Close to two-thirds (19/29) correctly answered that there may be gender/sex differences in how people respond to HIV treatment. More than half (17/29) responded “true” to the statement that study was meant to benefit their personal health (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Responses from ACTG 5366 participants related to the understanding of the study at entry visit (n = 29).

Details about study agents

Women were asked to describe the study drugs, vorinostat, and tamoxifen. 6/29 women identified vorinostat as a latency reversal agent, and 14/29 alluded to its use in cancer treatment, including breast cancer. Tamoxifen was described by 3/29 as a female hormone receptor modulator, by 3/29 as helping vorinostat wake up latent virus, and by 15/29 as a treatment of cancer. However, 4/29 were unsure about the purpose of the vorinostat and 2/29 about the purpose of tamoxifen. Only 1/29 incorrectly described tamoxifen as the latency reversal agent.

Perceptions of risks and benefits

Identified risks and benefits

When ACTG 5366 study participants were asked at entry about risks of participating in the study, 6/29 women responded that there was no risk involved, 21/29 responded that there were risks involved, and 2/29 did not know. When asked to specify risks, 11 free text responses submitted included possible side effects. One woman indicated that she did know the specific risks. When asked if there were any benefits of participating in the study, the majority of women responded “yes” (24/29), while 4/29 responded “no,” and 1/29 responded “don't know.” In free text responses to specify the benefits, 11 women referred to helping find a cure for HIV, 3 referred to possible health benefits, and 1 referred to the psychological benefits. Five women identified compensation as helping with their participation and two women wrote that the study might cure them as a benefit (Table 2).

Table 2.

Responses from AIDS Clinical Trials Group 5366 Participants Around Perceived Risks and Benefits of Study at Entry

| Themes | Quotes received |

|---|---|

| Are there any risks to participating in this study? | |

| Side effects (11 responses) | • “Possibility of having side effects” |

| • “Possible side effects of the medication” | |

| • “Could experience some side effects” | |

| • “Possible side effects” | |

| • “The medications have some side effects” | |

| • “Side effects of drugs” | |

| • “The side effects form the study medications” | |

| • “Possible Secondary Effects” | |

| • “Symptoms from the meds” | |

| • “A reaction to the drugs” | |

| • “Drug can make me nauseous and I can get bruises from punctures” | |

| Other responses (5 responses) | • “There is a risk for everything” |

| • “There are minimal risk to all studies” | |

| • “I don't know how it is going to work” | |

| • “You may and or may not qualify” | |

| • “Always” | |

| Don't know what risks are (n = 1) | • “I don't know what they are” |

| Are there any benefits to participating in this study? | |

| Helping find a cure for HIV (11 responses) | • “Helping finding a cure” |

| • “Help find a cure” | |

| • “May find a cure for HIV” | |

| • “Finding a cure for AIDS and HIV” | |

| • “To find possible HIV cure” | |

| • “Finding a cure to HIV & AIDS” | |

| • “Finding a cure for AIDS and HIV” | |

| • “It enables me to look anxiously to a cure” | |

| • “Help others” | |

| • “Learn if this combo helps flush HIV out of reservoirs” | |

| • “The virus that is hiding in my body will be destroyed, even if it's just for a while” | |

| Health benefits (3 responses) | • “Living a healthier life. Live longer” |

| • “Medical Evaluations and Laboratory [Test Results]” | |

| • “My health doing well” | |

| Psychological benefits (1 response) | • “Psychological” |

| Compensation (1 response) | • “Compensation” |

| Mixed responses (4 responses) | • “Adding to science and the $25 compensation” |

| • “Yes your time is not wasted (…) you are being apart of something that can insure life” | |

| • “To see how the medication effects the virus and compensation” | |

| • “It can help researchers find answers and compensation cards” | |

| Other or miscellaneous (1 response) | • “There might be” |

| Cure for HIV (2 responses) | • “May be cured” |

| • “It maybe cure” [sic] | |

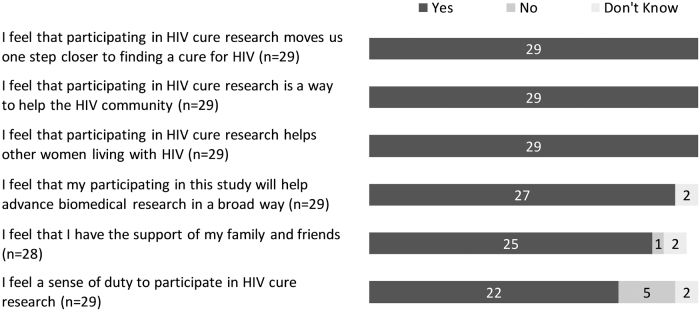

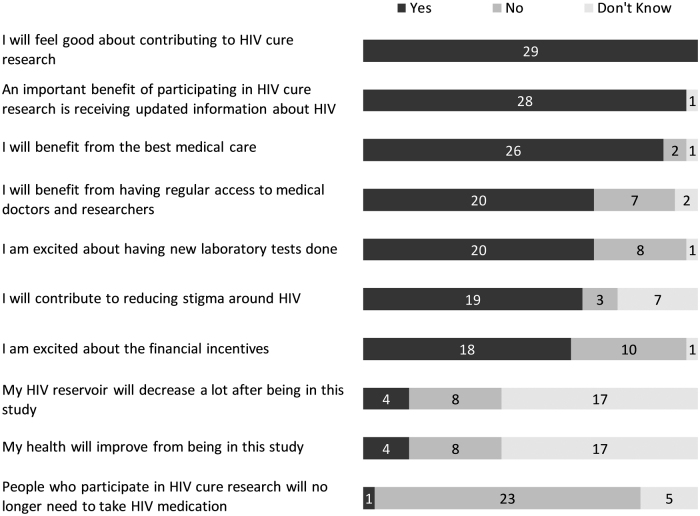

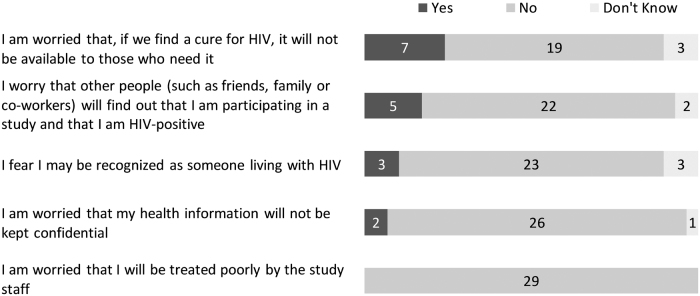

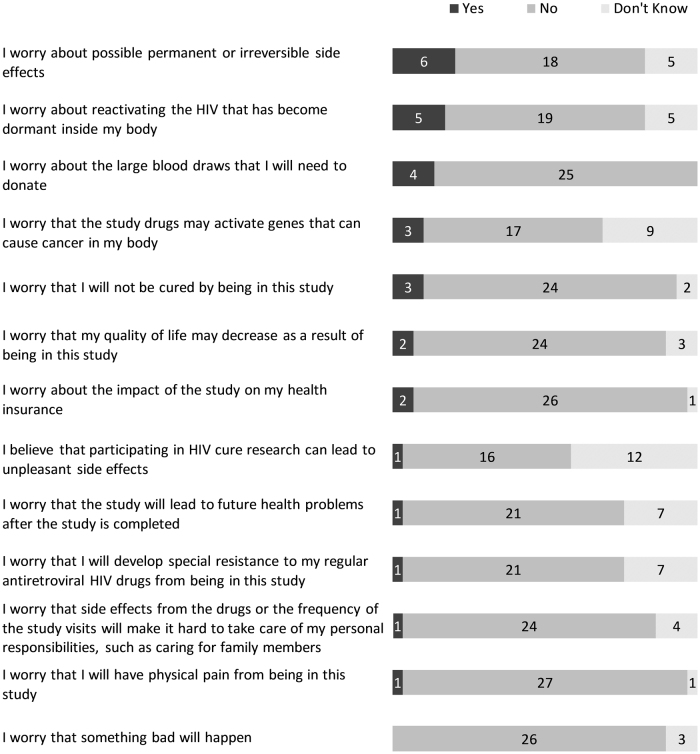

The entry survey included more structured, close-ended questions around perceived benefits and risks of being in the study. The three most prevalent perceived social benefits of the study were (1) moving one step closer to finding a cure for HIV (29/29), (2) helping the HIV community (29/29), and (3) helping other women living with HIV (29/29) (Fig. 4). When asked about perceived personal benefits, the three most prevalent answers were (1) feeling good about contributing to HIV cure research (29/29), (2) receiving updated information about HIV (28/29), and (3) benefiting from the best medical care (26/29) (Fig. 5). The three most prevalent social risks of being in the study included: (1) having a cure for HIV that is not available to those who need it (7/29), (2) other people finding out about study participation and HIV-positive status (5/29), and (3) being recognized as someone living with HIV (3/29) (Fig. 6). When asked about perceived personal risks, the three most prevalent answers were (1) possible permanent or irreversible side effects (6/29), (2) HIV reactivation inside the body (5/29), and (3) large blood draws needed for the study (4/29) (Fig. 7).

FIG. 4.

Perceived social benefits of the ACTG 5366 study at entry visit (n = 29).

FIG. 5.

Perceived personal benefits of the ACTG 5366 study at entry visit (n = 29).

FIG. 6.

Perceived social risks of the ACTG 5366 study at entry visit (n = 29).

FIG. 7.

Perceived personal risks of the ACTG 5366 study at entry visit (n = 29).

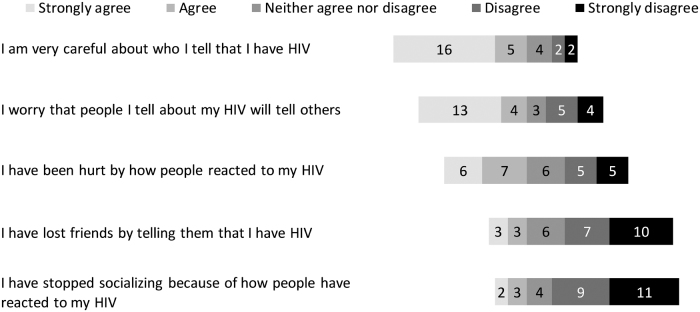

Self-image and perceived stigma

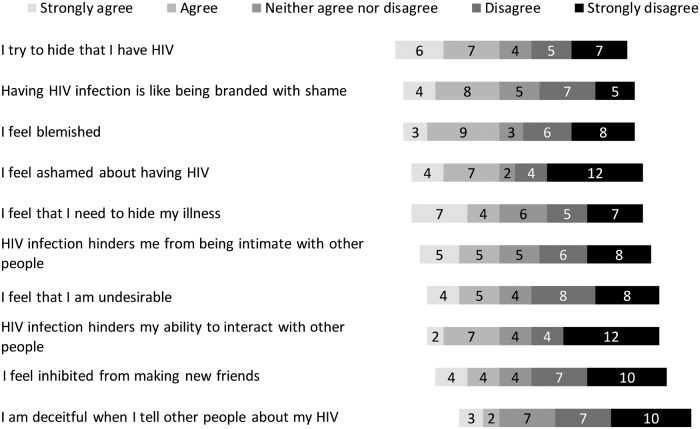

In addition to the open-ended and structured questions around motivators of participation, ACTG 5366 participants were specifically asked whether negative feelings about HIV influenced their decision to participate in the study. Over a quarter (8/29) said that negative feelings played a role in their decision to join the study. Explanations included: “I am tired of feeling alone,” “[it's] not easy to explain,” “I hate this disease,” “the stigma has been toxic to me” and “I hate living with the virus and it played a role in me participating in the study.” With regard to external stigma, 21/29 agreed or strongly agreed that they were very careful about disclosure of their HIV diagnosis (Fig. 8). With regard to internal stigma, 13/29 agreed or strongly agreed that they were hiding their HIV seropositive status, 12/29 agreed or strongly agreed that having HIV was like being branded with shame, and 12/29 felt blemished (Fig. 9).

FIG. 8.

Perceptions of external stigma for ACTG 5366 study participants at entry visit (n = 29).

FIG. 9.

Perceptions of internal stigma for ACTG 5366 study participants at entry visit (n = 29).

Role of compensation for ACTG 5366 clinical trial

The entry survey concluded by asking women about the role of compensation in joining the ACTG 5366 clinical study. When asked if they were offered compensation, 17/29 said “yes” and described compensation as money, gift cards, or parking, 9/29 said “no,” and 3/29 did not know. Of the 15 women who responded to the question “Do you feel this compensation is sufficient?,” 11/15 said “yes,” explaining “fair for time involved,” “covers the basics,” and “it's enough” and 4/15 said “no” with reasons including “time is worth more,” “the visits are quite long and travel expenses are expensive,” and “incentive is small compared to other studies.”

When asked about the importance of compensation 10/17 disagreed and 7/17 agreed that reimbursements/study stipends facilitated their participation in the study by defraying some of the costs and time associated with their involvement with the trial. Reasons for disagreeing with the statement included: “I didn't join because of money,” “it's not enough money to make me join a study, but it's appreciated” and “the evaluations are more important.” Reasons for agreeing with the statement were the following: “might help me to pay for my parking, cab fare, getting me to the doctor,” “parking,” “it helps me pay for some bills and transportation.” We also asked ACTG 5366 participants if they considered reimbursements to be a potential benefit of the clinical study. Of the 28 women who responded, 24/28 said “yes” indicating “it's nice to be paid for your time and travel to clinic” and “it's a way of showing respect.”

Exit surveys

At the end of the study, 27 women completed the exit survey (demographic data not shown). All but one replied that they would recommend the study to others. Representative statements given for recommending the study to others included: “no bad experience during the course of the study,” “this study was easy to do with little side effects,” “did not require anything invasive,” “because when you join you learn so many things that can help with having HIV,” “because we don't have enough women doing research with HIV,” “be part of something greater than self,” and “every opportunity to advance medical science is a wonderful opportunity for [the] human condition.”

When asked if the study would provide information that is important to advancing the field of HIV cure-related research, 22/27 strongly agreed. Perceived benefit categories included feeling good about contributing to science, health benefits, gaining knowledge, compensation, and other mixed responses (Table 3).

Table 3.

Perceived Benefits from AIDS Clinical Trials Group 5366 Study Respondents at the End of the Study

| Themes | Quotes received |

|---|---|

| Did you benefit from participating in this study? | |

| Feeling good about contributing to science (5 responses) | • “I feel like I've helped the researchers learn more about HIV and anything they can learn is a direct to me” |

| • “Hopefully help science move along” | |

| • “Because I helped out others which made me feel good” | |

| • “It gave me an immense satisfaction that I was given an opportunity to be part of this study” | |

| • “Because helping research with medications needed for HIV” | |

| Health benefits (3 responses) | • “Getting medication for my health to make my health better” |

| • “I was monitored closely” | |

| • “For me to know what's going on in my body (…)” | |

| Gaining knowledge (3 responses) | • “Gained knowledge” |

| • “I learned more about reservoirs than I knew before” | |

| • “It was a learning tool for me” | |

| Compensation (2 responses) | • “I benefited from the gift cards” |

| • “Yeah got extra cash” | |

| Mixed responses (3 responses) | • “Getting my labs performed and receiving the test results. Learning about different medications. Taught me discipline about taking my HIV meds” |

| • “My benefit is not just the money it is helping to find a cure, giving my blood to help I find to be a good thing besides I was put here to help” | |

| • “Medical follow-up, laboratory tests and treatment that can benefit [others]” | |

| Other or miscellaneous (1 response) | • “Yes, I do feel I've benefited from this study” |

Women were asked if they would be willing to volunteer for another similar study in the future and all (n = 27) answered “yes.” One woman explained as follows: “I have not lost anything by participating but the science may have gained information toward a cure.” Using structured questions, we asked about problems related to participation in the study. 24/27 did not report any problem. However, 2/27 reported finding HIV cure-related research very complicated to understand, 2/27 felt stigma from participating in the study, 1/27 reported parking problems, and 1/27 reported “Other—too much blood at each visit.” Finally, we asked participants if they felt valued as study participants. 25/27 answered “yes,” 1/27 answered “no,” and 1/27 answered “don't know.”

Discussion

Our findings provide unique insights into the perspectives of women enrolled in a single multisite small trial conducted across the United States, who have been traditionally underrepresented in HIV research.3 To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine how women living with HIV perceived and experienced participation in such a study. The nested social science surveys yielded a rich dataset examining the experiences of people living with HIV in cure-related research.18–20 We identified societal and personal motivators for participation, understanding of risks and benefits, and some misconceptions in a minority of trial participants. Almost all women had a very positive experience participating in the ACTG 5366 trial, and would recommend the study to others. Using these findings could help in the design, implementation, recruitment, and retention of women in HIV cure-related research, highlighting the value of assessing psychosocial and affective factors in HIV cure-related research participation. Importantly, our study showed the feasibility of integrating participant-centered outcomes, here an assessment of how needs of participants were met, in an intensive multi-site HIV cure-related interventional trial.

Our findings strengthen the proposition that a thorough examination of how participants perceive and experience HIV cure-related research has ethical significance.18 Research teams are responsible for ensuring participants understand the nature of early-phase research: namely, that scientific findings are incremental, and that studies will not be curative. Trial teams should also be attentive to participants' needs throughout the study.15,22 Participants themselves can provide unique insights into the best way to optimize their trial experience while minimizing harms, including social harms.

The surveys uncovered a host of reasons why ACTG 5366 participants decided to join the study. These included a mix of societal and altruistic reasons around helping find a cure for HIV, combined with the desire to personally benefit and improve one's health. The desire to help advance science, combined with the need for personal benefits mirrors those found previously in the HIV cure18,19,23 and other fields (e.g., HIV prevention24 or oncology25,26). Almost all respondents indicated that they were satisfied with the informed consent process and understood the study as helping advance HIV cure-related science. Some showed a sophisticated understanding of the study and its purpose. However, we noted misunderstandings in a minority of participants (e.g., the belief that tamoxifen was the latency-reversing agent).

Interestingly, a small subset of women seemed to believe that the ACTG 5366 study could potentially cure them, despite that the ACTG 5366 informed consent form avoided the use of the word “cure.” Scholars have discouraged the use of the word “cure” entirely in study-related documents to avoid participant misconceptions about the potential for cure from these early-phase investigations.17,27 Using terms that more precisely describe the mechanisms being studied (e.g., latency reversal) can go a long way in setting realistic expectations28–30 but can also at times be overly technical. Biomedical HIV cure research teams must also ensure adequate comprehension from study participants to ensure they are joining studies for appropriate reasons.31 Others have suggested increasing the readability of informed consent forms,29 and using decision-making checklists.32 Undoubtedly, biomedical HIV cure research teams should appreciate the psychological dimensions of HIV cure-related research participation.19,27 As bioethicists have previously posited, it is possible that participants' seemingly high expectations of clinical benefits may simply have reflected their hopes.26,33

The surveys also revealed general understanding of the associated risks and benefits, but some lack of recall about specific details. Over two-thirds recognized that there were risks involved, but most had difficulty naming specific clinical risks. The ACTG 5366 informed consent form contained three pages detailing the possible risks of the study, including the risks of vorinostat and tamoxifen, risks of nonstudy medications, risks of drawing blood, risks of electrocardiogram, risks of social harms, risks of stored samples, and risks of future study participation. Our finding that participants had difficulty recalling specific clinical risks seems consistent with previous sociobehavioral research.20,29 This finding further raises the question of whether risk information should be simplified or participants should be engaged in a discussion about risks during follow-up study visits.

Notably, over half believed that the study would benefit their personal health and the majority emphasized the likelihood of societal and personal (e.g., health and psychological) benefits. However, the ACTG 5366 informed consent form clearly stated that participants would “receive no benefit from being in this study.” This apparent contradiction has been witnessed elsewhere,18,20 and has led scholars to advocate for ethics committees and biomedical research teams to take inclusion benefits into account.34–36 Some intangible benefits identified by participants included a sense of contributing to science and more frequent evaluation in clinical settings. The topic of altruistic benefits, such as feeling good about helping advance HIV cure-related science, emerged prominently throughout the survey responses for almost all ACTG 5366 study participants. This finding parallels similar sociobehavioral research where stated altruism was the most commonly cited reason for joining HIV cure-related studies.19,20,37,38 Given the early-phase nature of the ACTG 5366 study, participation should rest principally on altruism and aspirational societal benefits.39 Fostering a healthy sense of altruism and responsibly emphasizing societal benefits may facilitate HIV cure research participation.38 From an ethical standpoint, however, altruistic outlook should not unduly distort risk perceptions for experimental interventions, particularly in “otherwise healthy volunteers” who may have more to lose.40,41

Importantly, survey findings revealed the pervasive role of stigma in women's lives, and in decisions to join HIV cure-related studies, even for very healthy women living with HIV. This finding aligns with focus groups conducted in the United States where participants strongly valued the possible destigmatizing effect of no longer having HIV.42 Once again, more research is needed to better understand how stigma and self-image may act as motivators or barriers to HIV cure-related research participation, particularly for women.43

Reimbursement for the time involved in research participation appears to have played a role in decisions to participate. For at least one-third of women, reimbursements facilitated their participation in the study. Furthermore, the majority perceived reimbursements as a benefit of being in the study. This finding is ethically relevant, since IRBs do not recognize compensation as a benefit.44–46 While ethics committees do not generally recognize compensation as a benefit, and research teams do not present reimbursements as benefits, it is possible that study participants still genuinely perceive them as such. Stipends to defray the costs of study participation may play an important role in motivating participants, women in particular, and in helping them overcome barriers to research participation.

At the end of the study, we were surprised and encouraged to find such high satisfaction from the ACTG 5366 participants. Almost all women stated that they would recommend the study to others and would volunteer for another similar study in the future. The majority believed the information gained would advance the field of HIV cure-related research and endorsed benefiting from the study. The very few problems experienced included finding HIV cure-related research difficult to understand, feeling stigma, parking problems, and having too much blood drawn.

A major strength of our study is the collection of participant-centered data at two critical time points: entry and exit. Nonetheless, we must acknowledge a number of limitations. The baseline survey was administered ∼1 month after enrollment and informed consent, and may have been subject to recall bias. We did not collect participant reports longitudinally throughout the study and may have missed fluctuations in attitudes better captured by real-time assessments. We also focused on specific domains of inquiry using semistructured surveys, which may not have conveyed the richness of meaning, variations in responses, and uniqueness of participant's experiences that would be provided by in-depth interviewing. Further, we did not survey those who chose not to enroll in the study nor assess their reasons for refusing to participate in the ACTG 5366 study.16 Since participants had to be postmenopausal and “otherwise healthy volunteers,” data may not generalize to all women living with HIV in the United States or in other settings. We also do not have a comparable study of men for comparison and cannot determine if features of the participant's experiences are unique to women or shared. Future studies should collect more in-depth psychological characteristics of study participants to obtain a more complete picture of health. These shortcomings notwithstanding, we believe that our findings have high internal validity and add to the literature of women's participation in HIV cure-related research.

Table 4 includes a summary of key findings and possible implications for HIV cure-related research.

Table 4.

Summary of Findings and Possible Implications for HIV Cure-Related Research

| Themes | Possible implications |

|---|---|

| Decisions to participate in research | • HIV cure researchers should recognize that people living with HIV may join trials for a variety of reasons. |

| • ACTG 5366 participants joined the study for a combination of reasons, including societal and altruistic benefits of contributing to science, and the desire to personally benefit. | • People living with HIV, and women in particular, may need to consult with important people in their lives before making decisions to participate. |

| Understanding of the study | • The word “cure” should be avoided in all study-related documents. Precise terms that describe study mechanisms may go a long way in setting realistic expectations. |

| • Most ACTG 5366 participants understood the study as helping advance HIV cure-related science. Some women showed a sophisticated understanding of the study. | • Biomedical HIV cure researchers should ensure adequate comprehension of study participants. This may require repeated communication during study follow-up. |

| • Over half thought the study would personally benefit their personal health. | • Increasing the readability of informed consent forms or using informed decision-making checklists could be helpful in enhancing understanding. |

| • We noted minor misunderstandings about the study in a subset of participants. | • The psychological aspects of research participation should be appreciated. Study participants should also be provided with adequate psychological counseling and support. |

| • A small number believed the study could possibly result in a cure. | • Ascertaining the existence of therapeutic or curative misconception requires in-depth probing of study participations. |

| • Further empirical research is needed to examine how participants understand various HIV cure studies and interventions. | |

| Perceptions of risks and benefits | • Biomedical HIV cure research teams should simplify risk information during the informed consent process, and provide refreshers during study visits. |

| • The majority of ACTG 5366 participants understood that some risks were involved, but had difficulty naming specific clinical risks. | • Biomedical HIV cure research teams should ascribe value to the lived experiences of study participants. This is particularly important for research involving women. |

| • ACTG 5366 participants valued the likelihood of health and psychological benefits, while the informed consent form emphasized there would be no direct benefit. | • Attention should be paid to how risks and benefits are communicated to study participants. |

| • Information should be collected on how participants perceive and understand risks and benefits of research, with the close involvement of social scientists in a multi-disciplinary research effort. | |

| • Biomedical HIV cure research teams should emphasize the incremental nature of scientific discovery and that initial studies will not be curative. | |

| • While biomedical HIV cure research teams can explain to participants that they will be closely monitored, it should be emphasized that experimental study interventions are not meant to benefit participants's health directly, but to advance biomedical science. | |

| Meaning of the study and altruism | • Biomedical HIV cure research teams should foster a healthy sense of altruism, while ensuring altruistic outlook does not unduly distort risk perceptions. |

| • Several ACTG 5366 participants gave altruistic reasons for joining the study. These altruistic motivations were also mixed with the desire for personal benefit. | • Future HIV cure studies should explore how participants weigh various motivations—including altruistic intentions versus self-oriented motivations. |

| • In-depth empirical research is needed to precisely characterize the type of altruism witnessed in HIV cure-related study participants. | |

| Self-image and perceived stigma | • Biomedical HIV cure research teams should appreciate that, despite being otherwise healthy, participants may still need to cope with various layers of stigma in daily life. |

| • Stigma remains a pervasive reality in the lives of several women who volunteered for the ACTG 5366 study, and appears to have played a role in decisions to join the study. | • More research is needed to better understand the role of stigma and self-image in decisions to participate or stay involved in research. |

| Role of compensation | • Monetary compensation may be a motivational factor for women, particularly in overcoming barriers to research participation (e.g., transportation), although it should not be construed as a benefit according to ethical guidelines. |

| • Compensation was cited as facilitating participation by at least one third of participants, and played a role in decisions to participate for some women. | |

| Exit survey | • It is possible to recruit women in HIV cure-related research, if attention is paid up front to protocol design. |

| • Almost all ACTG 5366 participants would recommend the study to others and would volunteer again. | • HIV cure researchers should help women reduce barriers and enhance facilitators to participation. This would help ensure that decisions are based on participant preferences and autonomy, instead of systemic barriers. |

| • Only few women reported problems with research participation (e.g., finding the research difficult to understand, stigma, parking problem, and too much blood drawn). | • Exit surveys are helpful to understand factors affecting participant satisfaction and practical challenges encountered. |

ACTG, AIDS Clinical Trials Group.

Conclusion

In sum, the ACTG 5366 trial was the first women-only HIV cure-related protocol implemented in the United States. The study showed that it is possible to recruit and retain women in HIV cure-related research, and to embed participant-centered outcomes at strategic time points during the study. Our study identified societal and personal motivators for participation, understanding of risks and benefits, and minor misconceptions in some trial participants. Results point to the need for continued engagement and clarification of participant expectations throughout the entire course of trial implementation. Given the paucity of similar prospectively collected data from participants in HIV cure-related trials, further work will be needed to identify features specific to women, particularly for studies involving HIV treatment interruptions. Careful inclusion of women in HIV cure-related research studies, combined with sex/gender-based analyses, will also be crucial for the design of interventions that are efficacious in and acceptable for all people living with HIV.12 Ensuring representation of women in HIV research will remain a fundamental issue of equity and justice.47 Our research underscores the feasibility of a robust and multidisciplinary HIV cure research agenda to examine participant values, perceptions, and lived experiences.48,49 Together with meaningful community and stakeholder engagement, monitoring participants' psychosocial experiences will be crucial to understand, from their points of view, the factors that will enhance the acceptability of interventions. As the biomedical sciences continue to evolve toward an HIV cure, it will be critical to appreciate both the biomedical and the sociobehavioral dimensions of this research enterprise. Ultimately, to develop medical products that are patient-centered, we will need to encourage a framework of research that centers around participants, and what they consider to be most meaningful.

Acknowledgments

The ACTG 5366 study team is indebted to all the women who participated in the study, and volunteered their time for both the biomedical study and the social sciences surveys. We also thank the ACTG 5366 study team, the ACTG Clinical Research Sites, ACTG 5366 Study Coordinators, and Social & Scientific Systems, Inc., for their assistance with the study. We are most grateful to the ACTG Cure Transformative Science Group (TSG), the Women's Health Inter-Network Scientific Committee (WHISC), the ACTG Community Scientific Sub-Committee, and the ACTG Leadership for supporting this study. We also thank Katie Mollan and Angela Stover from the R21MH118120 study team, and the R21MH118120 external advisory team. We are grateful to Jo Gerrard of the University of California, Riverside School of Medicine, who provided editorial assistance for this article.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The ACTG 5366 study corresponds to NCT03382834.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award numbers: UM1 AI068634, UM1 AI068636, UM1 AI069412, and UM1 AI106701. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to K.D. (R21MH118120). K.D. is also grateful for support received from the amfAR Institute for HIV Cure Research (amfAR 109301), UM1AI126620 (BEAT-HIV Collaboratory) cofunded by NIAID, NIMH, NINDS, and NIDA and AI131385 (P01 Smith—Revealing Reservoirs during Rebound [R3]—Last Gift).

References

- 1. UNAIDS. Women and Girls and HIV. 2018. Available at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/women_girls_hiv_en.pdf

- 2. CDC: HIV among women. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/index.html, accessed September18, 2019

- 3. Curno MJ, Rossi S, Hodges-Mameletzis I, Johnston R, Price MA, Heidari S: A systematic review of the inclusion (or exclusion) of women in HIV research: From clinical studies of antiretrovirals and vaccines to cure strategies. JAIDS 2016;71:181–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smeaton LM, Kacanek D, Mykhalchenko K, et al. : Screening and enrollment by sex in HIV clinical trials in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2019;29:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barr L, Jefferys R: A landscape analysis of HIV cure-related clinical trials and observational studies in 2018. J Virus Erad 2019;5:212–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johnston R, Heitzeg M: Sex, age, race and intervention type in clinical studies of HIV cure: A systematic review. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2015;31:85–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Klein SL, Flanagan KL: Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Publ Gr 2016;16:626–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Klein SL, Jedlicka A, Pekosz A: The Xs and Y of immune responses to viral vaccines. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10:339–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Griesbeck M, Scully E, Altfeld M: Sex and gender differences in HIV-1 infection. Clin Sci 2016;130:1435–1451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scully EP: Sex differences in HIV infection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2018;15:136–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scully EP, Street NW: Sex differences in HIV infection: Mystique versus machismo. Pathog Immun 2018;3:82–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gianella S, Tsibris A, Barr L, Godfrey C: Barriers to a cure for HIV in women. J Int AIDS Soc 2016;19:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Das B, Dobrowolski C, Luttge B, et al. : Estrogen receptor-1 is a key regulator of HIV-1 latency that imparts gender-specific restrictions on the latent reservoir. PNAS 2018;115:7795–7804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. ClincalTrials.gov: Selective estrogen receptor modulators to enhance the efficacy of viral reactivation with histone deactylate inhibitors. Available at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03382834, accessed September18, 2019

- 15. Dubé K, Barr L, Palm D, Brown B, Taylor J: Putting participants at the centre of HIV cure research. Lancet HIV 2019;3018:18–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peay H, Henderson G: What motivates participation in HIV cure trials? A call for real-time assessment to improve informed consent. J Virus Erad 2015;1:51–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Julg B, Dee L, Ananworanich J, et al. : Recommendations for analytical treatment interruptions in HIV Research Trials. Report of a Consensus Meeting. Lancet HIV 2019;6:e259–e268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Henderson GE, Peay HL, Kroon E, et al. : Ethics of treatment interruption trials in HIV cure research: Addressing the conundrum of risk/benefit assessment. J Med Ethics 2018;44:270–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Henderson GE, Waltz M, Meagher K, et al. : Going off antiretroviral treatment in a Closely Monitored HIV ‘Cure’ Trial: Longitudinal assessments of acutely diagnosed trial participants and decliners. J Int 2019;22:e25260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gilbertson A, Kelly EP, Rennie S, Henderson G, Kuruc J, Tucker JD: Indirect benefits in HIV cure clinical research: A qualitative analysis. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2019;35:100–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Palinkas LA, Aarons GA: Mixed method designs in implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Heal 2011;38:44–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cox K, Avis M: Ethical and practical problems of early anti-cancer drug trials: A review of the literature. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 1996;5:90–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dubé K, Evans D, Sylla L, et al. : Willingness to participate and take risks in HIV cure research: Survey results from 400 people living with HIV in the U.S. J Virus Erad 2017;3:40–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buchbinder SP, Metch B, Holte SE, Scheer S, Coletti A, Vittinghoff E: Determinants of enrollment in a preventive HIV vaccine trial: Hypothetical versus actual willingness and barriers to participation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004;36:604–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Luschin G, Habersack M, Gerlich I: Reasons for and against participation in studies of medicinal therapies for women with breast cancer: A debate. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Godskesen T, Nygren P, Nordin K, Hansson M, Kihlbom U: Phase 1 clinical trials in end-stage cancer: Patient understanding of trial premises and motives for participation. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:3137–3142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moodley K, Staunton C, Rossouw T, de Roubaix M, Duby Z, Skinner D: The psychology of ‘cure’. Unique challenges to consent processes in HIV cure research in South Africa. BMC Med Ethics 2019;20:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Henderson GE: The ethics of HIV ‘cure’ research: What can we learn from consent forms? AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2014;31:1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dubé K, Taylor J, Sylla L, et al. : ‘Well, It's the Risk of the Unknown… Right?’: A qualitative study of perceived risks and benefits of HIV cure research in the United States. PLoS One 2017;12:1–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rennie S, Siedner M, Tucker JD, Moodley K: The ethics of talking about ‘HIV cure’. BMC Med Ethics 2015;16:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chin LJ, Berenson JA, Klitzman RL: Typologies of altruistic and financial motivations for research participation: A qualitative study of MSM in HIV vaccine trials. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2016;11:299–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Verheggen FWSM, Jonkersb R, Kokb G: Patients’ perceptions on informed consent and the quality of information disclosure in clinical trials. Patient Educ Couns 1996;29:137–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kass N, Taylor H, Fogarty L, et al. : Purpose and benefits of early phase cancer trials: What do oncologists say? What do patients hear? J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2008;3:57–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rennie S, Day S, Mathews A, et al. : The role of inclusion benefits in Ethics Committee Assessment of Research Studies. Ethics Hum Res 2019;41:13–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lantos JD: The ‘inclusion benefit’ in clinical trials. J Pediatr 1999;134:130–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. King N: Defining and describing benefit appropriate in clinical trials. J Law Med Ethics 2000;28:332–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Evans D: An activist's argument that participant values should guide risk-benefit ratio calculations in HIV cure research. J Med Ethics 2017;43:100–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Balfour L, Corace K, Tasca GA, Tremblay C, Routy JP, Angel JB: Altruism motivates participation in a therapeutic HIV Vaccine Trial (CTN 173). AIDS Care 2010;22:1403–1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dresser R: First-in-human HIV-remission studies: Reducing and justifying risk. J Med Ethics 2017;43:78–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Verheggen FW, Nieman F, Jonkers R: Determinants of patient participation in clinical studies requiring informed consent: Why patients enter a clinical trial. Patient Educ Couns 1998;35:111–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dubé K, Dee L, Evans D, et al. : Perceptions of equipoise, risk—Benefit ratios, and ‘otherwise healthy volunteers' in the context of early-phase HIV cure research in the United States: A qualitative inquiry. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2018;13:1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sylla L, Evans D, Taylor J, et al. : If we build it, will they come? Perceptions of HIV cure-related research by people living with HIV in four U.S. cities—A qualitative focus group study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2018;34:56–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Auerbach J, Evans D: Integrating Social Research into the HIV Cure Agenda. Towards an HIV Cure - Engaging the Community Workshop. 2016. International AIDS Society; Durban, South Africa, July 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brown B, Galea JT, Dubé K, et al. : The need to track payment incentives to participate in HIV research. IRB Ethics Hum Res 2018;40:8–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gelinas L. Largent EA, Cohen IG, Kornetsky S, Bierer BE, Fernandez Lynch H: A framework for ethical payment to research participants. N Engl J Med 2018;378:766–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wertheimer A: Is payment a benefit. Bioethics 2013;27:105–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Grewe ME, Ma Y, Gilbertson A, Rennie S, Tucker JD: Women in HIV cure research: Multilevel interventions to improve sex equity in recruitment. J. Virus Erad 2016;2:e15–e17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Grossman CI, Ross AL, Auerbach JD, et al. ; International AIDS Society (IAS) ‘Towards an HIV Cure’ Initiative: Towards multidisciplinary HIV-cure research: Integrating social science with biomedical research. Trends Microbiol 2016;24:5–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dubé K, Auerbach JD, Stirratt MJ, Gaist P: Applying the behavioural and social sciences research (BSSR) functional framework to HIV cure research. J Int AIDS Soc 2019;22:e25404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]