Summary

An outpatient radiotherapy department assessed how precautions implemented during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak affected patient satisfaction with doctor–patient interaction and explored variables potentially influencing satisfaction. The information obtained would help prepare us for future infectious disease outbreaks. Outpatients seen during the outbreak completed a validated questionnaire assessing satisfaction with doctor–patient interaction. Additional items assessed included patients’ perception of SARS measures and patient demographics. Of 149 patients, 97% had heard of SARS, 92% believed SARS precautions necessary, and 54% believed contracting SARS was possible despite the precautions. Patients were satisfied with doctors wearing masks (97%), temperature checks (97%), and patients wearing masks (96%). Despite the high satisfaction levels with SARS precautions, 24% believed it had adversely affected doctor–patient interaction. With regards to doctor–patient interaction, 94% of patients were satisfied. Patients were most satisfied with the ‘information exchange’ domain (mean score 3.23 out of 4) compared to other domains (P < 0.0001, 100.00% confidence) and were less satisfied with the ‘empathy’ domain compared to other domains (P < 0.0001, 100.00% confidence). Patients were most satisfied with understanding their treatment plan (100%), doctor being honest (97%) and being understood (96%). Patients were least satisfied with information about caring for their illness (61%), that the visit could be better (59%), and the doctor showing more interest (58%). On multivariate analysis, patients who were less satisfied with SARS measures were significantly less satisfied with doctor–patient interaction (P = 0.0001). Dissatisfaction with SARS measures was associated with significant dissatisfaction for questions in all domains. Older age and non‐breast cancer patients were also less satisfied with doctor–patient interaction. Most (94%) of patients were satisfied with doctor–patient interaction, despite implementation of infectious disease prevention measures. However, patients who were dissatisfied with the SARS precautions had poorer satisfaction. In particular, physician empathy appeared to be most adversely affected. The results have relevance to any radiotherapy department preparing contingency plans in the event of infectious disease outbreaks.

Keywords: doctor–patient interaction, patient satisfaction, radiotherapy, severe acute respiratory syndrome

Introduction

Since the global outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), there have been concerns about its high prevalence among health‐care workers and their household members 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 . The disease is thought to be caused by the Coronavirus and transmission via the airborne route 7 , 8 , 9 . The disease can progress rapidly and often results in acute respiratory distress syndrome, with many cases fatal 10 .

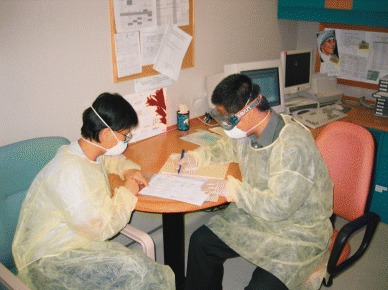

Singapore reported its first three cases of SARS on 13 March 2003 11 . As the number of infected patients increased, more drastic measures were instituted 12 , 13 , 14 . These included closure of schools, travel advisories to SARS‐affected areas, Home Quarantine Orders to persons exposed to SARS patients or returning from SARS‐affected areas and increased education on good social behaviour (e.g. to avoid spitting in public). Violations of these laws were punishable by fines and/or jail terms. By 31 May 2003, SARS had infected 206 people in Singapore, with slightly more than half of those infected being health‐care workers or hospital inpatients 15 . In order to control the transmission of SARS from patient to health worker, the Ministry of Health enforced strict hospital infection control protocols to help break the chain of transmission 16 . These measures included compulsory SARS screening for all patients, relatives and visitors. This involved temperature checks both at the main entrances and at entrances to all departments, compulsory filling in of a SARS exposure risk questionnaire, compulsory use of personnel protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves, gown, goggles and N‐95 mask by health‐care workers, and wearing of mask and gown by patients (Fig. 1). The hospital also implemented a ‘no visitor’ rule (with a limit of one visitor if there were compassionate grounds), restricted physical access into hospitals, and implementation of a 1 week on, 1 week off team approach for all staff, that is, radiotherapy centre staff were divided into two groups with each alternating group working every other week. At the National University Hospital (NUH) Radiotherapy Centre, these measures were strictly enforced.

Figure 1.

Consultation with personnel protective equipment.

There is increasing importance placed by the patient on the quality of the doctor–patient interaction 17 , 18 , 19 . Levels of satisfaction are thought to influence compliance, communication, continuity of care, promptness to seek help, patient's level of understanding and retention of information, all of which are essential in the delivery of high‐quality clinical care 20 , 21 , 22 . We wished to evaluate patient satisfaction during the SARS outbreak, and we postulated that satisfaction with doctor–patient interaction might be adversely affected by perception of SARS preventive measures.

Thus, our primary aim was to measure the level of patient satisfaction with their doctor–patient interaction during the SARS outbreak using a questionnaire previously validated for radiotherapy outpatient consultation 23 . Our secondary aim was to determine what factors, including patient perception of SARS precautions, age, tumour type and stage, might affect satisfaction with doctor–patient interaction. It was believed the information obtained would be useful for any radiotherapy centre preparing contingency planning for infectious disease outbreaks – a time when patient satisfaction might be considered of secondary importance.

Methods and materials

The questionnaire instrument consisted of two parts. The first part incorporated a previously validated 29‐question patient satisfaction questionnaire (questions 1–29, Table 1) specific for radiotherapy centre outpatient visits 23 . This questionnaire was designed to evaluate four aspects (or ‘domains’) of doctor– patient interaction: information exchange, interpersonal skills, empathy and quality of time. We also added one additional question assessing ‘overall’ satisfaction (question 30).

Table 1.

. Satisfaction with doctor‐patient interaction: questionnaire and results of survey

| Domains and items | Response categories (n = 149) | Mean† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly agree (%) | ||

| Information exchange domain | 3.23 | ||||

| Q1: I will follow the doctor's advice because I think he/she is absolutely right. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 62.4 | 37.6 | 3.38 |

| Q2: I really felt understood by my doctor. | 0.0 | 4.0 | 69.8 | 26.2 | 3.22 |

| Q3: After my last visit with my doctor, I feel much better about my concerns. | 1.4 | 4.8 | 66.0 | 27.9 | 3.20 |

| Q4: I understand my illness much better after seeing this doctor. | 2.8 | 11.7 | 60.7 | 24.8 | 3.08 |

| Q5: This doctor was interested in me as a person and not just my illness. | 0.7 | 14.4 | 58.2 | 26.7 | 3.11 |

| Q6: I feel I understand pretty well the doctor's plans for helping me. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 66.4 | 33.6 | 3.34 |

| Q7: After talking with the doctor, I have a good idea of what changes to expect in my health over the next few weeks and months. | 0.0 | 8.1 | 68.9 | 23.0 | 3.15 |

| Q8: The doctor told me to call back if I had any questions or problems. | 0.0 | 7.4 | 62.8 | 29.7 | 3.22 |

| Q9: I felt the doctor was being honest with me. | 1.4 | 2.0 | 60.1 | 36.5 | 3.32 |

| Q10: The doctor explained the reason why treatment was recommended for me. | 0.0 | 4.7 | 63.8 | 31.5 | 3.27 |

| Interpersonal skills domain | 2.93 | ||||

| Q11: The doctor did not take my problem very seriously. | 17.8 | 64.4 | 11.6 | 6.2 | 2.94 |

| Q12: The doctor did not give me all the information I thought I should have been given. | 15.0 | 64.4 | 16.3 | 4.1 | 2.90 |

| Q13: I didn’t have a chance to say everything I wanted or to ask all my questions. | 20.3 | 62.8 | 15.5 | 1.4 | 3.02 |

| Q14: The doctor was not friendly to me. | 30.6 | 59.9 | 6.1 | 3.4 | 3.18 |

| Q15: I would not recommend this doctor to a friend. | 21.8 | 61.3 | 14.1 | 2.8 | 3.02 |

| Q16: The doctor seemed to brush off my questions. | 20.1 | 66.7 | 11.1 | 2.1 | 3.05 |

| Q17: The doctor should have told me more about how to care for my condition. | 8.3 | 31.0 | 49.7 | 11.0 | 2.37 |

| Q18: It seemed to me that the doctor wasn’t really interested in my physical well‐being. | 19.2 | 63.0 | 14.4 | 3.4 | 2.98 |

| Empathy domain | 2.78 | ||||

| Q19: The doctor considered my individual needs when treating my condition. | 3.5 | 12.5 | 67.4 | 16.7 | 2.97 |

| Q20: There were some things about my visit with the doctor that could have been better. | 7.9 | 32.9 | 54.3 | 5.0 | 2.44 |

| Q21: It seemed to me that the doctor wasn’t really interested in my emotional well‐being. | 16.8 | 65.7 | 13.3 | 4.2 | 2.95 |

| Q22: The doctor seemed rushed today. | 18.6 | 64.8 | 14.5 | 2.1 | 3.00 |

| Q23: The doctor should have shown more interest. | 7.6 | 34.5 | 51.7 | 6.2 | 2.44 |

| Q24: There were aspects of my visit with the doctor that I was not very satisfied with. | 11.9 | 63.6 | 21.7 | 2.8 | 2.85 |

| Quality of time domain | 2.97 | ||||

| Q25: The doctor went straight to my medical problem without first greeting me. | 18.1 | 68.1 | 13.2 | 0.7 | 3.03 |

| Q26: The doctor used words I did not understand. | 13.3 | 65.7 | 17.5 | 3.5 | 2.88 |

| Q27: There wasn’t enough time to tell the doctor everything I wanted. | 16.4 | 62.3 | 19.9 | 1.4 | 2.94 |

| Q28: I feel the doctor did not spend enough time with me. | 16.0 | 65.3 | 17.4 | 1.4 | 2.96 |

| Q29: I feel the doctor diagnosed my condition without enough information. | 18.3 | 70.4 | 9.9 | 1.4 | 3.06 |

| Summary question | |||||

| Q30: Overall, I am satisfied with my doctor–patient interaction. | 0.7 | 7.0 | 65.0 | 27.3 | 3.19 |

| Mean Satisfaction Index for all patients. | 3.02 | ||||

Mean of transformed scores, so that for each question (whether positively or negatively framed) a high score is equivalent to higher satisfaction.

For the second part of the questionnaire (Table 2), we designed 15 questions assessing the level of patient knowledge and satisfaction with SARS precautions. The second part also included two open‐ended questions to allow patients to express other opinions regarding satisfaction (questions 44 and 45, Table 2). Questions were designed with the aid of staff and patients.

Table 2.

. Knowledge and perception of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) precautions: questionnaire and results of survey

| Domains and items | Response categories (n = 149) | Mean† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly agree (%) | ||

| General questions about SARS knowledge | |||||

| Q31: I have heard about SARS. | 0.0 | 2.7 | 70.1 | 27.2 | NA |

| Q32: I have heard that the National University Hospital is taking precautions to prevent the spread of SARS. | 0.7 | 2.7 | 66.7 | 29.9 | NA |

| Q33: I believe that there may be a risk of contracting SARS when I visit the Radiotherapy Centre. | 4.1 | 42.1 | 46.9 | 6.9 | NA |

| Q34: I am more careful in my everyday life due to the SARS outbreak in Singapore. | 25.9 | 71.4 | 2.0 | 0.7 | NA |

| Satisfaction with SARS precautions | 3.09 | ||||

| Q35: I am satisfied about having my temperature checked each day when entering the Radiotherapy Centre. | 0.0 | 3.4 | 72.4 | 24.1 | 3.21 |

| Q36: I am satisfied about wearing a mask at all times while in the Radiotherapy Centre. | 0.7 | 3.4 | 74.1 | 21.8 | 3.17 |

| Q37: I am satisfied that there are restrictions on friendsor relatives entering the Radiotherapy Centre with me. | 2.1 | 9.6 | 72.6 | 15.8 | 3.02 |

| Q38: I am satisfied about the doctor wearing a mask, gown, gloves and goggles when seeing me. | 1.4 | 1.4 | 67.8 | 29.5 | 3.25 |

| Q39: I am satisfied about the nurses and therapists wearing masks, gowns, gloves and goggles when attending me. | 0.7 | 2.7 | 64.4 | 32.2 | 3.28 |

| Q40: I am satisfied that access to my own specialist consultant doctor may be less due to the SARS precautions. | 0.7 | 22.7 | 66.0 | 10.6 | 2.87 |

| Q41: I believe the SARS precautions being taken by the Radiotherapy Centre are necessary. | 0.0 | 7.6 | 58.6 | 33.8 | 3.26 |

| Q42: I am satisfied that there may be a delay in being seen by my doctor because of the SARS precautions. | 1.4 | 18.5 | 63.0 | 17.1 | 2.96 |

| Q43: The SARS precautions that the Radiotherapy Centre is taking have made me less satisfied with my doctor–patient interaction. | 7.7 | 69.2 | 18.9 | 4.2 | 2.80 |

| Open‐ended question s | |||||

| Q44: What other factors have positively affected your doctor–patient interaction? Please list. | |||||

| Q45: What other factors have negatively affected your doctor–patient interaction? Please list. | |||||

Mean of transformed scores, so that for each question (whether positively or negatively framed) a high score is equivalent to higher satisfaction.

NA, not applicable.

For every question, patients were asked to indicate their agreement (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree). Responses were scored out of 4, with 1 correlating to least satisfied, and 4 to most satisfied. Any average score of > 2.5 indicated satisfaction. Satisfaction was also averaged across each domain of the original questionnaire (i.e. for the four domains of ‘information exchange’, ‘interpersonal skills’, ‘empathy’ and ‘quality of time’).

To be eligible for the survey, patients had to consult a doctor at the NUH radiotherapy centre from 19 May 2003–31 May 2003 and be aged 18 years or older with intact cognition. Patients were asked to anonymously fill in the questionnaire after the consultation. Patients were asked to deposit completed questionnaires into a closed survey box placed in the separate patient waiting area.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), except for confidence levels 24 , which were calculated with a calculator spreadsheet 25 . Uni and multivariate analyses evaluated the following patient characteristics: age, sex, race, spoken language (English vs Chinese), paying class, tumour type, cancer stage, type of visit, presence of family member, education level, time waiting for consultation, and satisfaction with SARS measures.

Results

During the 2‐week survey period, there were a total of 197 first‐consultation patient attendances at the radiotherapy centre as compared to an average attendance of 311 first‐consultation patients pre‐SARS over the same timeframe. Of the 197 patients, 11 were ineligible because of young age or cognition. Of the remaining 186 eligible patients, 174 agreed to participate and 149 questionnaires were returned (response rate of 80%). Patient characteristics are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

. Patient characteristics

| Patient age (years) | |

| Median | 53.0 |

| Range | 6.0–84.0 |

| Gender (n (%)) | |

| Male | 49 (32.9) |

| Female | 100 (67.1) |

| Ethnic group (n (%)) | |

| Chinese | 126 (84.6) |

| Malay | 11 (7.4) |

| Indian | 5 (3.3) |

| Other | 7 (4.7) |

| Does patient speak English (n (%)) | |

| No | 56 (37.6) |

| Yes | 93 (62.4) |

| Paying class (n (%)) | |

| Private | 26 (17.4) |

| Subsidized | 123 (82.6) |

| Cancer primary type (n (%)) | |

| Breast | 62 (41.6) |

| Lung | 29 (19.5) |

| Gastric | 10 (6.7) |

| Colorectal | 9 (6.0) |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | 17 (11.4) |

| Lymphoma | 9 (6.0) |

| Other | 13 (8.7) |

| Cancer stage (n (%)) | |

| In situ | 0 (0.0) |

| Stage I | 32 (21.5) |

| Stage II | 52 (34.9) |

| Stage III | 28 (18.8) |

| Stage IV | 37 (24.8) |

| Visit type (n (%)) | |

| New patient | 26 (17.4) |

| Follow up | 55 (36.9) |

| Treatment review | 34 (22.8) |

| Mold room | 1 (0.7) |

| Simulation | 15 (10.1) |

| Radiotherapy treatment | 18 (12.1) |

| Was family member present? (n (%)) | |

| No | 92 (61.7) |

| Yes | 57 (38.3) |

| Patient's maximum level education (n (%)) | |

| No school | 0 (0.0) |

| Elementary school | 51 (34.2) |

| Secondary school | 67 (45.0) |

| College | 13 (8.7) |

| University | 11 (7.4) |

| Postgraduate school | 7 (4.7) |

| Time spent waiting (min) | |

| Median | 15.0 |

| Range | 0–120 |

| Language of patient questionnaire (n (%)) | |

| English | 88 (59.1) |

| Chinese | 61 (40.9) |

SARS questions

Overall, 97% of patients had heard about SARS (Table 2, question 31) and 97% had heard that the hospital was taking precautions to prevent the transmission of SARS (question 32). However, 54% of patients still believed they were at risk of contracting SARS despite the measures (question 33). Overall, 92% of respondents believed the implementation of SARS measures was necessary, and the vast majority of patients were satisfied with individual precautionary measures. Of note, 20% of patients were dissatisfied that there might be a delay in seeing their doctor because of SARS measures, 23% were dissatisfied that they might have less access to their specialist consultant, and 12% were dissatisfied about restrictions on visitors. In addition, 23% of patients believed that the SARS precautions had adversely affected their doctor–patient interaction.

Doctor–patient satisfaction

Overall, 92% of patients were satisfied with their doctor–patient interaction (Table 1, question 30). There were three questions where, on average, patients were dissatisfied (means score < 2.5): questions 17, 20 and 23. Of note, 61% of patients felt that the doctor should have told them more about how to care for their condition (question 17), 59% of patients believed that there were some things about the doctor visit that could have been better (question 20), and 58% believed that the doctor should have shown more interest (question 23).

Patients were most satisfied with items within the ‘information exchange’ domain (average domain score 3.23). There were significantly more patients satisfied with this domain than the other three domains (P < 0.0001, 100.0% confidence). Patients were least satisfied with items within the ‘empathy’ domain (mean domain score 2.78). There were significantly fewer patients satisfied with this domain than each of the other domains (P < 0.0001, 100.0% confidence). Satisfaction with ‘interpersonal skills’ (mean domain score 2.93) and ‘quality of time’ (mean domain score 2.97) had intermediate satisfaction levels.

On univariate analysis, significant associations were found between a number of variables and increased satisfaction with doctor–patient interaction, including female patients (P = 0.04), private‐class patients (P = 0.03), breast cancer patients (P = 0.02), patients using the English questionnaire (P = 0.01), patients who have heard of SARS (P = 0.002), satisfaction with SARS precautionary measures (P < 0.001), and younger patient age (P = 0.05). On multivariate analysis, a patient's satisfaction level was reduced as one advanced in age (P = 0.01), for non‐breast cancer patients (P = 0.04), and for patients less satisfied with the SARS prevention measures (P < 0.001).

For factors found significant on multivariate analysis, we explored the possibility that different factors might impact on different domains of doctor–patient interaction. Age was found to significantly (all P < 0.05) affect questions 11–15 of the questionnaire, which are wholly within the ‘interpersonal skills’ domain of the instrument. Cancer type affected answers to question 17 only, which also belongs to the ‘interpersonal skills’ domain (P = 0.02). Satisfaction with SARS measures was significantly (all P < 0.05) associated with differences in all questions except questions 12 and 20. Thus, satisfaction with all domains appeared to be influenced by perception of SARS precautionary measures. These results are interesting, but should be viewed as hypothesis generating in view of the multiple significance tests performed.

Only 21 patients (14%) took the opportunity to voice additional comments (questions 44–45). Of these, 10 gave negative responses, and eight gave positive responses, and three patients gave both positive and negative comments. The negative comments were related to SARS measures in 11 respondents. Problems included patients having to wear masks (3), the no visitor rule (3), long waiting times (2), doctor wearing mask thus difficult to hear (1), taking of patient temperatures (1), and unable to see the same doctor each time because of the week‐on, week‐off roster (1). One of these patients also mentioned the long route to the radiotherapy centre due to triage being at the hospital front entrance and closure of many entrances and exits: the patient said that this caused her to feel tired and weak. Two patients had negative comments not directly related to SARS precautions: the doctor speaking too fast, appearing insensitive, not interested and looking rushed (1), and language barrier (1).

Also of interest was one patient's positive comment: ‘My doctor has a genuine interest in me. The mask makes my doctor look really professional and I don’t feel alienated by it. In fact, it boosts my confidence that RTC [the Radiotherapy Centre] is taking SARS precautions seriously’.

Anecdotally, one patient became extremely distressed and aggressive when told relatives were not allowed, and required restraining. Another patient openly wept throughout the consultation because of the no visitor rule. As a result of the anonymous nature of the questionnaire, it is uncertain how (or whether) these patients responded.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that patients’ compliance to treatment and hence the success of their treatment depends on their satisfaction with their doctor–patient interaction 18 , 19 , 20 , 26 , 27 . In multiethnic Singapore, cultural and subcultural influence is strong, thus achieving patient satisfaction is challenging. This is made more difficult with inherent problems of communication because of language barriers between doctor and patient, and non‐disclosure at the family's request. With the outbreak of SARS, implementation of infection control measures were strictly enforced and education about the need for such measures was communicated through the media. Despite such efforts, confidence in these measures was still low, with more than half of patients surveyed believing that contraction of SARS was still possible despite preventive measures. This might explain the sharp drop in attendance at the radiotherapy centre during the SARS crisis as compared to the pre‐SARS period.

As we expected, patients who were less satisfied with the SARS prevention measures were also less satisfied with doctor– patient interaction. We postulated that patients might feel alienated by doctors wearing goggles, gown and masks (Fig. 1), feel less secure without relatives present, be frustrated by longer waiting times, and be dissatisfied that every second week they would not see their treating consultant because of the week‐on, week‐off roster. We believed that patients who were more satisfied with such measures would be more tolerant to potential deterioration of doctor–patient interaction, and hence would be more satisfied with questionnaire items. Based on the uni and multivariate analyses, we appear to be correct in our assumption. Dissatisfaction with SARS measures was associated with dissatisfaction in all doctor–patient interaction domains.

The appearance of donning one's PPE (goggles, mask, gloves and gown – Fig. 1) can cause, in the eyes of some patients, intimidation, insensitivity and possibly be both a physical and emotional barrier. One example was that in order to minimize patient contact, greeting patients with a handshake was discouraged. Another example is mask wearing, which is uncomfortable, and in Singapore made worse because of hot weather and high humidity. However, patients were, overall, satisfied in wearing their mask and seeing their doctors wearing a mask. This may be as a result of a sense of security in believing that by wearing on a mask, patients were less likely to get transmission of the airborne SARS virus and they were happy to sacrifice personal comfort.

The effect of the no visitor rule meant that patients could not bring someone along for their consultation, unless they appealed on compassionate grounds. This might have created further dissatisfaction, as there were no familiar faces around for the patient during discussion of their treatment or to provide emotional support as well as causing ‘anxiety to family members who were made to wait outside of the department’. As previously mentioned, these measures resulted in one patient having to be physically restrained, and another patient wept continuously throughout the consultation. However, despite these concerns, the majority of the patients were satisfied that these measures were implemented. Hence, maintaining infectious disease precautions might instill public confidence in the health‐care system, justifying the cost required to maintain preventive measures.

It is not surprising to note that older age is a significant predictive factor for patient dissatisfaction. Often in Asian societies, where decision‐making primarily lies with the family, older patients are not told of their diagnosis or prognosis 28 . There is a perception that if the diagnosis is revealed to the patient they might have difficulty dealing with the knowledge that they have cancer. Thus, in Singapore, the non‐disclosure rate is high (17% overall for our patients but 24% for patients aged 66–80 years old and 72% for patients over 80 years old 29 ). The lack of knowledge by the elderly patient because of non‐disclosure may affect doctor–patient satisfaction, as the elderly patient is not involved in the overall decision‐making process. They do not see a need for treatment and thus do not understand the rationale for treatment. Of interest was the fact that in our study, patient age only significantly influenced items within the ‘interpersonal skills’ domain of the questionnaire. This included questions on whether the patient thought enough information had been provided, whether sufficient opportunity had been given to ask questions and how friendly the doctor was.

Also of interest was our finding that non‐breast cancer patients were less satisfied with doctor–patient interaction. This was most strongly associated with the ‘interpersonal skills’ domain, in particular whether the doctor had told the patient enough about how to care for their condition. It is possible that radiation oncologists spend more time counseling breast cancer patients about this aspect compared to other cancer patients, and would be an interesting area for future research.

Our study has several potential limitations. First, it should be noted that patients in Singapore, a society with strict societal obedience and reluctance to question authority, might not be representative of patients in other non‐Chinese cultures. This would be a very interesting area for future research. Second, as infection control measures will undoubtedly vary depending on the type of infection, the applicability to other disease outbreaks is unknown. As far as we are aware, this is the only evaluation of patient satisfaction in an oncology setting during an infectious disease outbreak. Third, we used the only doctor–patient interaction satisfaction instrument validated for oncology outpatient visits. Although this instrument was developed for Western patients, it has not been specifically validated in Singapore (for either English or Chinese versions). Singapore is unique as it is a very westernized society with English as its working language; however, some elderly patients are not as competent in English. Our Chinese version of the instrument was professionally translated, assessed by our department's Chinese‐speaking staff, and cancer and non‐cancer patients, to ensure the accuracy, comprehension and face validity. Supporting Chinese instrument validity was the finding that instrument language was not associated with patient satisfaction on multivariate analysis. In addition, the original instrument was validated in an area of Canada ‘rich in cultural diversity’, including a large Chinese population 23 .

Our study has implications for our own and other centres, particularly when infection control processes are in place or being contemplated. First, it is apparent that despite dissatisfaction with individual aspects of the doctor–patient interaction, patients were satisfied overall. This was pleasing given the very strict infection control measures that were implemented. It is possible that awareness of the SARS outbreak, and of hospital precautions, might have prepared patients for any impact on doctor–patient interaction. Our multivariate analysis supports this hypothesis: the strongest predictor for satisfaction was a positive perception of SARS precautions. This may support costly public education media campaigns in the future to emphasize the need.

In addition, it might be possible to target department‐based patient education programs to further increase satisfaction. It is apparent that the ‘empathy’ domain, which had the lowest overall satisfaction for our patients, could be specifically targeted; in particular, doctors could be educated to show greater interest in patients despite infection control processes. In other domains, doctors could give patients more support for how to care for their condition and try to use more lay terms, particularly where masks already impair effective communication. It appears that older patients and non‐breast cancer patients need particular attention in our patient population. It would be interesting to confirm our findings in other cultures, and to investigate why these patient subgroups might be less satisfied. Further research is also indicated to investigate whether targeted interventions can increase satisfaction, and whether the lifting of infection control measures has any impact (positive or negative) on patient satisfaction with doctor–patient interaction.

JI Tang B Medicine; TP Shakespeare MB BS, MPH, FRANZCR, FAMS, GradDipMedClinEpid; XJ Zhang MD; JJ Lu MD; S Liang MSc(BioStat); CJ Wynne FRANZCR; RK Mukherjee MB BS, FRANZCR; MF Back MB BS, FRANZCR, GradDipPsyOnc.

References

- 1. From the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome – worldwide 2003. JAMA 2003;. 289: 1918–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Avendano M, Derkach P, Swan S. Clinical course and management of SARS in health care workers in Toronto: a case series. CMAJ 2003; 168: 1649–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization (WHO) [Internet]. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) – multi‐country outbreak – update. WHO, Geneva, 2003[cited September 2003]. Available from URL: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2003_03_16/en/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 4. Update: outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome – worldwide 2003. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003; 52: 241–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tsang KW, Ho PL, Ooi GC et al. A cluster of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1977–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koh D, Lim MK, Chia SE. SARS: health care work can be hazardous to health. Occup Med (Lond) 2003; 53: 241–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seto WH, Tsang D, Yung RW et al. Advisors of Expert SARS group of Hospital Authority. Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Lancet 2003; 361: 1519–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holmes KV. SARS coronavirus: a new challenge for prevention and therapy. J Clin Invest 2003; 111: 1605–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization Multicentre Collaborative Network for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Diagnosis. A multicentre collaboration to investigate the cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2003; 361: 1730–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ashraf H. Investigations continue as SARS claims more lives. Lancet 2003; 361: 1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ministry of Health . Three cases reported but no link to outbreak of atypical pneumonia established yet (Press release). Ministry of Health, Singapore, 13 March 2003[cited September 2003]. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.sg/corp/sars/news/updates.jsp?year=2003 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ministry of Health . Update on SARS (Press release). Ministry of Health, Singapore, 17 March 2003, 22 March 2003, 29 March 2003, 30 March 2003[cited September 2003]. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.sg/corp/sars/news/updates.jsp?year=2003 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mukherjee RK, Back MF, Lu JJ et al. Hiding in the bunker: challenges for a radiation oncology department operating in the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome outbreak. Australas Radiol 2003; 47: 143–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Prime Minister's Goh Chok Tong's Address. Fighting SARS together (Press release). Straits Times 2003;. 22 April.

- 15. Chang AL. Singapore is off WHO's SARS list (Press release). Straits Times 2003;. 31 May .

- 16. Tan CC. Responsibility of Health Care Institutions. Ministry of Health, Singapore, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oberst MR. Patients’ perceptions of care: measurement of quality and satisfaction. Cancer 1984; 53: 2366–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Covinsky KE, Bates CK, Davis RB et al. Physicians’ attitudes toward using patient reports to assess quality of care. Acad Med 1996; 71: 1353–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cromarty I. What do patients think about during their consultations? A qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 1996; 46: 525–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rubin HR, Gandek B, Rogers WH et al. Patients’ ratings of outpatient visits in different practice settings: Results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA 1993; 270: 835–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sinf JH, Weiss BD. Patient satisfaction with health care: intentions and change in plan. Eval Program Plann 1991; 14: 299–306. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ware JE, Davies AR. Behavioural consequences of consumer dissatisfaction with medical care. Eval Program Plann 1983; 6: 291–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Loblaw DA, Bezjak A, Bunston T. Development and testing of a visit‐specific patient satisfaction questionnaire: the Princess Margaret Hospital Satisfaction With Doctor Questionnaire. J Clin Oncol 1999; 6: 1931–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shakespeare TP, Gebski VJ, Veness MJ, Simes J. Improving interpretation of clinical studies by use of confidence levels, clinical significance curves, and risk‐benefit contours. Lancet 2001; 357: 1349–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shakespeare's Confidence Calculator v1. 0. [downloadable software; cited July 2003]. Shakespeare TP, Singapore, 2003.. Available from URL: http://;www.theshakespeares.com/confidence_calculator.html [Google Scholar]

- 26. Doyle BJ, Ware JE Jr. Physician conduct and other factors that affect consumer satisfaction with medical care. J Med Educ 1977; 52: 793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kane RL, Maciejewszki M, Finch M. The relationship of patient satisfaction with care and clinical outcomes. Med Care 1997; 35: 714–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ong KJ, Back MF, Lu JJ, Shakespeare TS, Wynne CJ. Cultural attitudes to cancer management in traditional South‐East Asian patients. Australas Radiol 2002; 46: 370–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Back M. Non disclosure in an Asian population (Abstract). Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists 52nd Annual Scientific Meeting Abstract Book. RANZCR, Sydney, 2002. [Google Scholar]