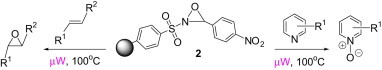

Abstract

A thermally stable polymer-supported oxidant has been developed. Polymer-supported 2-benzenesulfonyl-3-(4-nitrophenyl)oxaziridine was applied to microwave-assisted reactions that occurred at high temperatures and was shown to oxidize alkenes, silyl enol ethers, and pyridines to the corresponding epoxides and pyridine N-oxides in excellent to good yields and with much shorter reaction times. It also enabled tetrahydrobenzimidazoles to be oxidatively rearranged to spiro fused 5-imidazolones in a more efficient manner. Recycling of the polymer-supported oxidant is also possible with minimal loss of activity after several reoxidations.

Keywords: Polymer-supported 2-benzenesulfonyl-3-(4-nitrophenyl)oxaziridine, Microwave, Epoxide, Pyridine N-oxide, Spiro fused 5-imidazolone

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Advances in the use of polymers in organic synthesis1, 2, 3 have led to the development of improved technologies for the preparation of chemical libraries. In particular, the use of polymer-supported reagents4, 5, 6 in what is commonly referred to as polymer-assisted organic synthesis is an attractive technique that combines the advantages of solid-phase chemistry with those of solution-phase synthesis. In this technique, a polymer-bound reagent is added to a substrate in solution to effect a chemical transformation. At the end of the reaction, the polymer-bound spent reagent can be separated via filtration, thus simplifying product purification. Furthermore, since both the substrate and product are in solution during the reaction, conventional solution-phase analytical techniques, such as thin-layer chromatography, can be employed for reaction monitoring. The versatility of this methodology facilitates the process of library synthesis and has been the main stimulus for the recent growth of interest in polymer-supported reagents and catalysts.

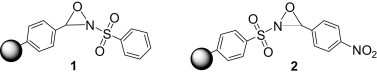

To date, various polymer-supported variants of commonly used reagents have been prepared and employed in numerous synthetic strategies.3, 7, 8, 9, 10 Amongst them, a number of oxidants, such as IBX,11 trimethylamine N-oxide,12 dichromate,13 and Swern oxidants14, 15 have been developed. Recently, we have reported the synthesis of a soluble polymer-supported 2-phenylsulfonyloxaziridine (Davis reagent) 1 (Fig. 1 ) and its application to the oxidation of sulfides, selenides, amines, phosphines, and enolates.16 Although polymer 1 effected clean and selective oxidation with high yields and simple workup, it was not thermally stable and could only be applied to reactions at ambient or low temperatures. To address the need of some oxidation reactions that occur much slower and require prolong heating for useful yields, we sought to develop a more stable form of polymer 1.

Fig. 1.

Polymer-supported 2-phenylsulfonyloxaziridines.

Davis and Sheppard had earlier reported the use of a thermally more stable 2-(phenylsulfonyl)-3-(p-nitrophenyl)oxaziridine for the oxidation of silyl enol ethers.17, 18 We reasoned that a polymer-supported version of this reagent would provide a thermally stable, neutral, aprotic, and mild polymer-supported oxidant that could contribute to a simpler and more convenient oxidative process. Hence we herein present the synthesis of soluble polymer-supported 2-benzenesulfonyl-3-(p-nitrophenyl)oxaziridine 2 and its application in the oxidation of various substrate types.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Synthesis of polymer 2

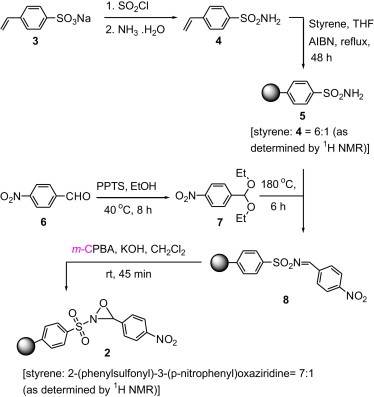

The synthesis of polymer 2 (Scheme 1 ) began with the conversion of the sodium salt of 4-styrenesulfonic acid 3 to 4-vinylbenzenesulfonamide 4. This was accomplished by first treating 3 with thionyl chloride to form the sulfonyl chloride, which was then reacted with ammonium hydroxide to provide 4. Polymerization of 4 with styrene using standard AIBN initiated radical polymerization afforded polymer 5 whose formation was amenable to KBr FTIR analysis (i.e., the appearance of primary sulfonamide bands at 3392 and 3269 cm−1). From elemental analysis data, the loading level of polymer 5 was calculated to be 1.20 mmol/g. This is consistent with the loading level of polymer 5 (∼1.2 mmol/g) determined via gel permeation chromatography (molecular weight of polymer 5=26,093) and 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of polymer 2.

Following the synthesis of polymer 5, we initially attempted to directly condense it with 4-nitrobenzaldehyde 6 to obtain polymer 8. Jennings and Lovely19 have shown that addition of TiCl4 to a mixture of aromatic aldehyde, sulfonamide, and triethylamine in CH2Cl2 gave the N-sulfonylimine after ca. 30 min at 0 °C. However, when the procedure was applied to 6 and polymer 5, the reaction had to be carried out under reflux in order for the reaction to proceed (entry 1, Table 1 ). Polymer 8 that precipitated from cold hexane was an impure product (as shown in the 1H NMR spectrum) and attempts to purify it proved difficult as the product surprisingly underwent hydrolysis when washed with cold methanol. This could be attributed to the presence of a Lewis acid in a protic solvent, which causes the imine nitrogen to become protonated, thus resulting in hydrolysis. Attempts to use other Lewis acids, such as TFAA,20 FeCl3,21 and Ti(OEt)4 22 gave very low loading levels of the product or no reaction at all (entries 2, 4, and 5, Table 1). To circumvent this problem, we converted 6 to 1-(diethyloxymethyl)-4-nitrobenzene 7, which was then reacted neat with polymer 5 at 180 °C to provide polymer 8.23 To prevent the hydrolysis of polymer 8, ethanol that formed as a by-product was distilled off immediately. This procedure gave a 78% conversion and the polymer 8 obtained was stable even when it was precipitated from cold methanol.

Table 1.

Synthesis of polymer 8 from polymer 5 and 4-nitrobenzaldehyde 6 or 1-(diethyloxymethyl)-4-nitrobenzene 7

| Entry | Condition | Reaction time (h) | % Conversiona |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TiCl4, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 6, reflux | 6 | 75 |

| 2 | FeCl3, EtOH, 6, rt | 24 | — |

| 3b | Amberlyst 15, 6, toluene, reflux | 24 | 25 |

| 4 | TFAA, 6, CH2Cl2, reflux | 24 | 30 |

| 5 | Ti(OEt)4, CH2Cl2, 6, reflux | 24 | 25 |

| 6 | 7, 180 °C | 6 | 78 |

Determined by comparing the loading of polymer 5 with the loading of polymer 8. Loading of polymer 5 was determined by elemental analysis whilst loading of polymer 8 was determined by 1H NMR.

Ref. 24.

Polymer 8 was subsequently oxidized with m-CPBA in the presence of KOH to polymer 2. Through 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of polymer 2 and elemental analysis, the loading of polymer 2 was determined to be ∼1.00 mmol/g.

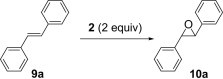

2.2. Oxidation of alkenes and silyl enol ethers

Like peracids, 2-sulfonyloxaziridines epoxidize alkenes in a syn stereospecific manner.25 However, compared to the peracids, oxidation with 2-benzenesulfonyl-3-(p-nitrophenyl)oxaziridine occurs much more slowly and a typical reaction requires 3–12 h of heating at 60 °C.26 With polymer 2 in our hands, we proceeded to examine such reactions using trans-stilbene 9a. As observed in solution-phase epoxidation, reaction of 9a with polymer 2 provided an observable change in color from an initial yellow solution to an intense yellow solution and with 1.25 equiv of polymer 2, the yield of 10a was 50% (entry 1, Table 2 ). To optimize the reaction, we varied the amount of polymer 2, the solvent and reaction condition. The best yield was obtained when the reaction was carried out in CH2Cl2 under microwave irradiation for 15 min (entry 5, Table 2).

Table 2.

| Entry | Solvent | Reaction condition | Yielda (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CH2Cl2 | Reflux, 4 h | 50b |

| 2 | CH2Cl2 | Reflux, 4 h | 73c |

| 3 | CH2Cl2 | Reflux, 4 h | 88 |

| 4 | CH2Cl2 | μW, 100 °C, 5 min | 42 |

| 5 | CH2Cl2 | μW, 100 °C, 15 min | 93 |

| 6 | THF | μW, 100 °C, 15 min | 87 |

| 7 | CHCl3 | μW, 100 °C, 15 min | 90 |

| 8 | Toluene | μW, 100 °C, 15 min | 67 |

Isolated yield.

Using 1.25 equiv of polymer 2.

Using 1.5 equiv of polymer 2.

To demonstrate the applicability of polymer 2 to the oxidation of alkenes, five other substrates were tested using the optimized reaction condition and good yields were obtained for all cases (Table 3 ). This shows that polymer 2 is able to oxidize alkenes in good yields and in a much shorter reaction time.

Table 3.

Epoxidation of alkenes using 2

Yield of isolated product.

Solution-phase reaction yield using 2-(phenylsulfonyl)-3-(p-nitrophenyl)oxaziridine (2 equiv), CHCl3, 60 °C, 12 h (Ref. 25).

Using polymer 1 (2 equiv), μW, 100 °C, CH2Cl2. Reaction was incomplete.

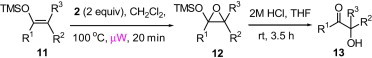

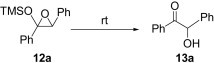

Encouraged by these results, we further explored the use of polymer 2 in the oxidation of silyl enol ethers 11 (Scheme 2 ). Under microwave irradiation at 100 °C, the oxidation was completed in 20 min and the α-silyl epoxide 12 that formed was isolated in quantitative yield. Compound 12 was then further treated with 2 M HCl (Table 4 ) to afford the corresponding α-hydroxy ketone in good yield (Table 5 ).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of α-hydroxy ketone from silyl enol ether.

Table 4.

Table 5.

Oxidation of silyl enol ether using 2

Isolated yield.

Purity of product ≥95%.

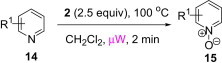

2.3. Oxidation of pyridine

Pyridine N-oxide derivatives are compounds of growing importance as there has been increasing interest in them as chiral controllers for asymmetric synthesis27 as well as inhibitors to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV),28 human SARS, and feline infectious peritonitis coronavirus.29 These N-oxides are typically prepared by oxidation of pyridines with hydrogen peroxide, peracids, sodium perborate or sodium percarbonate in the presence of catalysts.30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 To carry out the oxidation in a more environmentally friendly manner, various polymer-supported catalysts and solid-state oxidative processes have been developed.36, 37, 38 However the shortcomings of these methods are the requirement of higher temperatures or catalyst loading and long reaction times. To our knowledge, there are no earlier reports on the oxidation of pyridines with polymer-supported 2-phenylsulfonyloxaziridines. Hence in this work, we have investigated the performance of polymer 2 on such an oxidative reaction.

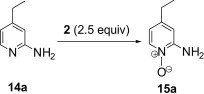

4-Ethyl-pyridin-2-ylamine 14a was used as a model substrate in the oxidation to the corresponding N-oxide with polymer 2 (2.5 equiv) employing the optimized conditions obtained by varying solvent and reaction conditions (Table 6 ). Under microwave irradiation at 100 °C, oxidation of 14a was completed in 2 min and 4-ethyl-pyridin-2-ylamine N-oxide 15a was obtained in quantitative yield (entry 3, Table 6). Application of this reaction condition to other pyridine analogs also resulted in good yields (Table 7 ).

Table 6.

| Entry | Solvent | Reaction conditions | Yielda (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CH2Cl2 | rt, 4 h | 93 |

| 2 | CH2Cl2 | μW, 60 °C, 25 min | 98 |

| 3 | CH2Cl2 | μW, 100 °C, 2 min | 99 |

| 4 | THF | μW, 100 °C, 25 min | 89 |

| 5 | CHCl3 | μW, 100 °C, 7 min | 96 |

| 6 | CH2Cl2 | μW, 100 °C, 14 min | 96b |

Isolated yield.

Using 1.2 equiv of 2.

Table 7.

| Entry | Substrate | Product | Yielda (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

|

92 |

| 2 |  |

|

91 |

| 3 |  |

|

82 |

Isolated yield.

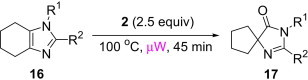

2.4. Oxidative rearrangement

In our earlier work,16 we have reported the rearrangement of tetrahydrobenzimidazoles to the corresponding 5-imidazolone using polymer 1. Since polymer 1 was not thermally stable, the rearrangement reaction had to be carried out at room temperature, which required 24 h to complete and provided the product in moderate yields (61–62%). To determine if the rearrangement would proceed more favorably at higher temperatures, we applied polymer 2 to the reaction. To begin, 1-methyl-4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-1H-benzimidazole 16a was dissolved in CH2Cl2 and treated with polymer 2 (2 equiv) under reflux for 6 h. To our delight, this gave 17a in 82% yield. Subsequently, we explored the reaction under microwave irradiation and found that at 100 °C, the reaction was completed within 45 min providing 17a in 85% yield. Applying this reaction condition to other analogs of 16 also resulted in good yields of the oxidative rearranged product (Table 8 ).

Table 8.

Isolated yield.

Solution-phase oxidative rearrangement using 2-benzenesulfonyl-3-phenyloxaziridine (2 equiv), CHCl3 at room temperature for 4 h (Ref. 39).

Isolated yield when the oxidative rearrangement was carried out with polymer 1 (2 equiv) at room temperature for 24 h.

Solution-phase oxidative rearrangement using 2-benzenesulfonyl-3-phenyloxaziridine (2 equiv), CHCl3 at 35 °C for 24 h (Ref. 39).

Isolated yield when the oxidative rearrangement was carried out with polymer 1 (2.5 equiv), 100 °C, μW, 45 min.

Solution-phase oxidative rearrangement using 2-(phenylsulfonyl)-3-(p-nitrophenyl)oxaziridine (2 equiv), CHCl3 at 35 °C for 24 h (Ref. 39).

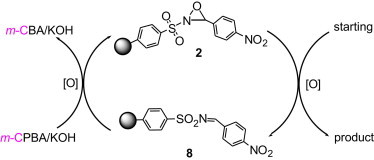

2.5. Recycling of 2

The reduced product of the oxygen transfer reaction with polymer 2 is polymer 8 (Scheme 3 ). To regenerate the oxidant, the spent polymer was reoxidized with m-CPBA/KOH. With careful repetitive regeneration of consumed 2, the loading levels could be restored to 0.8–1.0 mmol/g.

Scheme 3.

Recycling of polymer 2.

To determine the oxidative activity of regenerated 2, different oxidative reactions were performed to demonstrate the recycling possibility. Gratifyingly, the regenerated 2 was indistinguishable from polymer 2 and showed a slow decline in oxidative activity after multiple recovery steps (Table 9 ).

Table 9.

Recycling versus oxidative activity of 2

| Recycling | Yielda (%) |

|---|---|

| |

| Initial | 93 |

| First | 93 |

| Second | 91 |

| Third | 90 |

| Fourth | 89 |

| Fifth | 86 |

| |

| Initial | 85 |

| First | 83 |

| Second | 82 |

| Third | 80 |

| Fourth | 79 |

Isolated yield.

3. Conclusion

In summary, we have developed a thermally stable polymer-supported oxidant 2, which can be applied to reactions that occurred at elevated temperatures. With polymer 2, the microwave-assisted reactions at elevated temperatures generally required much shorter reaction times and gave excellent to good yields of the desired product. Polymer 2 was proven to be a potent oxidant, effecting clean and selective oxidation of alkenes, silyl enol ethers, and pyridines. It also enables tetrahydrobenzimidazoles to be oxidatively rearranged in an efficient manner to the spiro fused 5-imidazolones.

4. Experimental

4.1. General

All chemical reagents were obtained from Aldrich, Merck, Lancaster or Fluka and used without further purification. Moisture-sensitive reactions were carried out under nitrogen with commercially obtained anhydrous solvents. Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out on precoated plates (Merck silica gel 60, F254) and visualized with UV light or stained with the Dragendorff-Munier and Hanessian stain. Flash column chromatography was performed with silica (Merck, 230–400 mesh). NMR spectra (1H and 13C) were recorded at 298 K on a Bruker ACF300, DPX300 or AMX500 Fourier Transform spectrometers. Chemical shifts are expressed in terms of δ parts per million (ppm) relative to the internal standard tetramethylsilane (TMS). Mass spectra were performed on Finnigan TSQ 7000 for EI normal mode or Finnigan MAT 95XL-T spectrometer under EI, ESI, and FAB techniques. All infrared (IR) spectra were recorded on a Bio-Rad FTS 165 spectrometer. All isolated products are of ≥95% purity (by 1H NMR). Microwave reactions were performed on the Biotage Initiator™ microwave synthesizer.

4.2. Synthesis of 4-vinylbenzenesulfonamide 4

To an ice-cooled solution of the sodium salt of 4-styrenesulfonic acid 3 (10.3 g, 50 mmol) in dimethylformamide (DMF) (83 mL) under a nitrogen atmosphere was added thionyl chloride (30 mL, 413 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 6 h and then left in the fridge overnight. The solution was slowly poured into ice-water (150 mL) and extracted with ether (70 mL×3). The combined washing was dried with MgSO4 and concentrated to give the intermediate product, a sulfonyl chloride, which was then reacted with aqueous ammonium hydroxide (180 mL) for 2 h. Thereafter, the reaction mixture was extracted with ether and the combined ether extract was dried with MgSO4 and concentrated to give 4 as a white solid. Yield: 4.53 g (60%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 4.88 (s, 2H), 5.43 (d, 1H, J=10.7 Hz), 5.88 (d, 1H, J=17.7 Hz), 6.75 (dd, 1H, J=10.7 and 17.7 Hz), 7.52 (d, 2H, J=8.2 Hz), 7.87 (d, 2H, J=8.2 Hz). 13C NMR (acetone-d 6, 125 MHz) δ 115.9, 126.0, 126.1, 135.2, 140.6, 142.9. HRMS (EI): m/z=183.0354, calcd for C8H9O2NS: 183.0354.

4.3. Synthesis of polymer-supported benzenesulfonylamide 5

To a mixture of styrene (0.34 mL, 3 mmol) and 4 (0.091 g, 0.5 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (THF) (10 mL) was added AIBN (0.0025 g, 0.015 mmol). The reaction mixture was purged with argon for 30 min and then heated to reflux for 48 h. Thereafter, the reaction mixture was concentrated and the resulting residue was dissolved in THF (1 mL) and added slowly into vigorously stirred hexane (10 mL). The resulting suspension that formed was filtered by suction filtration and washed with cold methanol to afford polymer 5 as a white powder. Yield: 0.267 g (80%). Loading calculated from elemental analysis data: 1.30 mmol/g; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 1.43–1.84 (m, H2O+–CH2CH–), 6.58–7.60 (m, 40H, ArH). IR (KBr) ν=3078, 3059, 2921, 2850, 1492, 1452, 1338, 1163 cm−1.

4.4. Synthesis of 1-(diethoxymethyl)-4-nitrobenzene 7

Pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate (PPTS) (0.025 g, 0.1 mmol) was added to a solution of 4-nitrobenzaldehyde 6 (0.151 g, 1 mmol) in ethanol (10 mL). The solution mixture was heated for 12 h at 40 °C and then poured into brine solution and extracted with ethyl acetate (3×5 mL). The combined organic extract was then dried over MgSO4, concentrated, and purified by flash column chromatography using 1:9 (EtOAc/hexane) system to give 7 as a yellow liquid (Rf=0.32). Yield: 0.192 g (85%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 1.23 (t, 6H, J=7.0 Hz), 3.57 (m, 2H), 5.56 (s, 1H), 7.65 (d, 2H, J=8.8 Hz), 8.20 (d, 2H, J=8.8 Hz). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz) δ 15.1, 61.3, 100.1, 123.4, 127.7, 146.1, 147.9. HRMS (EI): m/z=225.1000, calcd for C11H15O4N: 225.1001.

4.5. Synthesis of polymer-supported N-benzenesulfonamide-p-nitro-benzylidene 8

1-(Diethoxymethyl)-4-nitrobenzene 7 (1.54 g, 6.83 mmol) and polymer-supported benzenesulfonamide 5 (8.45 g, 6.5 mmol) were added into a 100-mL single-necked round-bottomed flask equipped with short-path distilling head. The reaction mixture was heated at 180 °C in an oil bath until all the ethanol had ceased distilling over (∼6 h). After which, the reaction mixture was placed under high vacuum and cooled to room temperature. The crude solid product obtained was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (8 mL) and precipitated by slow addition into ice-cold CH3OH (25 mL). The suspension was then filtered by suction filtration to afford polymer 8 as a yellow solid. Yield: 75–80%. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 1.41–1.77 (m, H2O+–CH2CH–), 6.55–8.32 (m, 40H, ArH), 9.13 (s, 1H, CH). IR (KBr) ν=3082, 3060, 2923, 1595, 1527, 1346, 1162 cm−1.

4.6. Synthesis of polymer-supported 2-benzenesulfonyl-3-(p-nitrophenyl)oxaziridine 2

Polymer 8 (0.51 g, 0.5 mmol) was added to a white suspension of m-CPBA (70–75% purity, 0.216 g, 1.25 mmol) and powdered KOH (0.093 g, 1.65 mmol) in 5 mL of CH2Cl2 (previously prepared and stirred for 30 min at room temperature) and stirred for another 45 min. The reaction mixture was then filtered though Celite and the filter cake was washed with CH2Cl2 (10 mL×3). The combined filtrate and washings were concentrated to a small volume (∼3 mL) and added slowly into vigorously stirred ice-cold CH3OH (25 mL). The resulting suspension was filtered by suction filtration and dried in high vacuum to afford polymer 2 as a pale yellow powder; yield: 95–98%. Loading calcd by 1H NMR spectroscopy: 1.00 mmol/g and elemental analysis: 1.04 mmol/g. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ 1.43–1.84 (m, H2O+–CH2CH–), 5.57 (s, 1H, CH), 6.57–8.25 (m, 40H, ArH); IR (KBr): ν=3061, 3024, 2920, 2850, 1604, 1490, 1444, 1354, 1174, 1083, 1022 cm−1.

4.7. General procedure for alkene oxidation by polymer 2

Polymer 2 (0.6 mmol (based on the oxidizing equivalent)) was added to a solution of the respective alkene 9 (0.3 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (1.5 mL) placed in a sealed microwave vessel. The reaction mixture was microwave irradiated (with the heating program starting at 150 W) at 100 °C for 15 min. When the reaction is completed, the polymer-supported reagent was precipitated with ice-cold CH3OH (25 mL) and filtered through filter paper. The filter cake was then washed with ice-cold CH3OH (3×10 mL). The combined filtrate and washing was concentrated to 2–3 mL and filtered through a Miniart® single use syringe filter (pore size 0.2 μm) to remove any residual polymer. The filtrate was concentrated and purified using simple flash column chromatography to afford 10.

4.8. Preparation of silyl enol ether 11

The compound was synthesized according to a literature procedure.40

4.9. General procedure for silyl enol ether oxidation by polymer 2

Polymer 2 (0.6 mmol (based on the oxidizing equivalent)) was added to a solution of the respective silyl enol ether 11 (0.3 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (1.5 mL) placed in a sealed microwave vessel. The reaction mixture was then microwave irradiated (with the heating program starting at 150 W) at 100 °C for 20 min. When the reaction was completed, the polymer-supported reagent was precipitated with ice-cold CH3OH (25 mL) and filtered through a filter paper. The filter cake was then washed with ice-cold CH3OH (3×10 mL). The combined filtrate and washing was concentrated to 2–3 mL and filtered through a Miniart® single use syringe filter (pore size 0.2 μm) to remove any residual polymer. The filtrate was concentrated to dryness to afford the respective epoxide 12. The compound 12 was then stirred in a mixture of 2 M of HCl (3 mL) and THF (5 mL) and the hydrolysis reaction was monitored using TLC. When the reaction was completed, the reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc and the aqueous phase was extracted with EtOAc (5 mL). The combined organic extract was washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, filtered, concentrated, and purified by a simple flash column chromatography to afford the α-alcohol carbonyl compound 13.

4.10. General procedure for the oxidation of pyridines by polymer 2

Polymer 2 (0.75 mmol (based on the oxidizing equivalent)) was added to a solution of the respective pyridine 14 (0.3 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (1.5 mL) placed in a sealed microwave vessel. The reaction mixture was then microwave irradiated (with the heating program starting at 150 W) at 100 °C for 2 min. When the reaction was completed, the polymer-supported reagent was precipitated with ice-cold CH3OH (25 mL) and filtered through a filter paper. The filter cake was then washed with ice-cold CH3OH (3×10 mL). The combined filtrate and washing was concentrated to 2–3 mL and filtered through a Miniart® single use syringe filter (pore size 0.2 μm) to remove any residual polymer. The filtrate was concentrated to dryness to afford the respective compound 15.

4.11. Preparation of tetrahydrobenzimidazole 18

Compound 18 was synthesized according to a literature procedure.41

4.12. General procedure for oxidative rearrangement by 2

Polymer 2 (0.75 mmol) was added to a solution of the tetrahydrobenzimidazole 16 (0.3 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (2.0 mL) placed in a sealed-tube microwave vessel. The reaction mixture was microwave irradiated (with the heating program starting at 150 W) at 100 °C for 45 min. When the reaction was completed, the polymer-supported reagent was precipitated with cold methanol (25 mL) and filtered through filter paper. The filter cake was washed with cold methanol (3×10 mL) and the combined filtrate and washings was concentrated to 2–3 mL and filtered through a Miniart® single use syringe filter (pore size 0.2 μm) to remove any residual polymer. The filtrate was concentrated and purified by a simple flash column chromatography to give 17.

4.13. General procedure for the regeneration of polymer-supported 2-benzenesulfonyl-3-(p-nitrophenyl)oxaziridine 2

To a solution of m-CPBA (70–75% purity, 0.216 g, 1.25 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was added powdered KOH (0.093 g, 1.65 mmol) and the resulting suspension was stirred at room temperature for 30 min. Thereafter, the spent polymer (0.5 mmol) was added and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for an additional 45 min. After this, the reaction mixture was filtered though Celite and the filter cake was washed with CH2Cl2 (10 mL×3). The combined filtrate and washings were concentrated to a small volume (∼3 mL) and added slowly into vigorously stirred ice-cold CH3OH (25 mL). The resulting suspension was filtered by suction filtration and dried in high vacuum to afford polymer 2.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the National University of Singapore for the financial support provided (R-143-000-399-112).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.08.058.

Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data related to this article:

References and notes

- 1.Delgado M., Janda K.D. Curr. Org. Chem. 2002;6:1031. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graden H., Kann N. Curr. Org. Chem. 2005;9:733. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guino M., Hii K.K. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:608. doi: 10.1039/b603851b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ley S.V., Baxendale I.R., Bream R.N., Jackson P.S., Leach A.G., Longbottom D.A., Nesi M., Scott J.S., Storer R.I., Taylor S.J.J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 2000:3815. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirschning A., Monenschein H., Wittenberg R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solinas A., Taddei M. NATO Sci. Ser., II. 2008;246:253. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McNamara C.A., Dixon M.J., Bradley M. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:3275. doi: 10.1021/cr0103571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickerson T.J., Reed N.N., Janda K.D. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:3325. doi: 10.1021/cr010335e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heerbeek R.v., Kamer P.C.J., Leeuwen P.W.N.M.v., Reek J.N.H. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:3717. doi: 10.1021/cr0103874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett A.G.M., Hopkins B.T., Köbberling J. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:3301. doi: 10.1021/cr0103423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muelbaier M., Giannis A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:4393. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011203)40:23<4393::aid-anie4393>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frechet J.M.J., Darling G., Farrall M.J. Polym. Prepr. (Am. Chem. Soc., Div. Polym. Chem.) 1980;21:270. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamami B., Goudarzian N. Eur. Polym. J. 1992;28:1035. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris J.M., Liu Y., Chai S., Andrews M.D., Vederas J.C. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:2407. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi M.K.W., Toy P.H. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:7171. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao Y., Lam Y. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008;350:2937. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis F.A., Sheppard A.C. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:955. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis F.A. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:8993. doi: 10.1021/jo061027p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jennings W.B., Lovely C.J. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:5561. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee K.Y., Lee C.G., Kim J.N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:1231. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu X.F., Bray C.V., Bechki L., Darcel C. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:7380. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis F.A., Zhang Y., Andemichael Y., Fang T., Fanelli D.L., Zhang H. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:1403. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis F.A., Lamendola J., Nadir U., Kluger E.W., Sedergran T.C., Panunto T.W., Billmers R., Jenkins R., Jr., Turchi I.J., Watson W.H., Chen J.S., Kimura M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vishwakarma L.C., Stringer O.D., Davis F.A. Org. Synth. 1986;66:203. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis F.A., Abdul-Malik N.F., Awad S.B., Harakal M.E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:917. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oku A., Kinugasa M., Kamada T. Chem. Lett. 1993:165. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chelucci G., Murineddu G., Pinna G.A. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2004;15:1373. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevens M., Pannecouque C., De Clercq E., Balzarini J. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2951. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2951-2957.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balzarini J., Keyaerts E., Vijgen L., Vandermeer F., Stevens M., De Clereq E., Egberink H., Ranst M.V. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006;57:472. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Payne G.B., Deming P.H., Williams P.H. J. Org. Chem. 1961;26:651. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKillop A. Tetrahedron. 1989;45:3299. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jain S.L., Joseph J.K., Sain B. Synlett. 2006:2661. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colladon M., Scarso A., Strukul G. Green Chem. 2008;10:793. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tavakoli-Hoseini N., Bamoharram F.F., Heravi M.M. Synth. React. Inorg., Met.-Org., Nano-Met. Chem. 2010;40:912. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson D.J., McMorn P., Bethell D., Bulman-Page P.C., Sly C., King F., Hancock F.E., Hutchings G.J. Catal. Lett. 2001;72:233. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neimann K., Neumann R. Chem. Commun. 2001:487. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rout L., Punniyamurthy T. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2005;347:1958. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varma R.S., Naicker K.P. Org. Lett. 1999;1:189. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sivappa R., Koswatta P., Lovely C.J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:5771. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.06.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cazeau P., Moulines F., Laporte O., Duboudin F. J. Organomet. Chem. 1980;201:C9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lovely C.J., Du H., He Y., Dias H.V.R. Org. Lett. 2004;6:745. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.