Highlights

-

•

eMAG™ is a new nucleic acid extraction platform based on magnetic silica technology.

-

•

Performance of eMAG™ and easyMAG® were compared on various clinical specimens.

-

•

Agreement for virus detection ranged from 84.6% to 95.9%.

-

•

Correlation for virus quantitation displayed R2 from 0.802 to 0.995.

-

•

The two platforms showed comparable performance on the clinical specimens tested.

Keywords: eMAG™, easyMAG®, Nucleic acid extraction, Evaluation, Clinical specimens

Abstract

Background

eMAG™ (bioMerieux) is a new nucleic acid extraction platform based on magnetic silica technology, like its predecessor, NucliSENS® easyMAG® (bioMerieux). Using the same reagents and disposables, eMAG™ adds further automation, allowing simultaneous extraction of 48 samples directly from primary tubes, and distribution of nucleic acid extracts on PCR strips or in tubes at the end of the extraction process.

Objective

To compare the performance of eMAG™ and easyMAG® on various clinical specimens.

Study design

Respiratory (n = 199), whole blood (n = 50), plasma (n = 25) and urine (n = 25) specimens were extracted in parallel on both platforms. Both qualitative (respiratory virus, cell control, CMV, EBV, HHV6 and BKV detection) and quantitative (respiratory virus and cell control cycle thresolds, and CMV, EBV, HHV6 and BKV viral loads) results were compared.

Results

Detection of qualitative targets showed good agreement, ranging from 84.6% for whole blood to 95.9% for respiratory specimens. Correlations between quantitative results were good, with R2 ranging from 0.802 to 0.995. Quantitative results showed average overall differences below 0.10 log10 copies/mL between eMAG™ and easyMAG®.

Conclusions

The two platforms showed comparable performance on the types of clinical specimen tested. With higher automation and throughput than easyMAG®, the eMAG™ platform is likely to be advantageous for laboratories performing a large number of molecular analyses.

1. Background

Molecular analyses are now an essential part of virological diagnosis. Their high sensitivity, short turnaround time and ability to simultaneously detect and quantify multiple RNA and DNA viruses in small clinical samples have made them the gold standard for diagnosing and monitoring viral infections [1], [2], [3], [4]. Nevertheless, performance also depends partly on the amount and quality of extracted nucleic acids (NA). Poor extraction or incomplete removal of inhibitory molecules can significantly undermine the reliability of molecular diagnosis. Initially done by centrifugation or chemical separation, extraction is now mainly based on NA adsorption to silica in the presence of chaotropic salts such as sodium iodide, guanidine thiocyanate or guanidine hydrochloride, followed by elution with low-salt buffer or water [5], [6], [7], [8]. This silica-based technology, notably improved by Boom and colleagues, allowed the NA isolation procedure to be automated, ensuring better standardization and reproducibility [9].

Released in 2005, NucliSENS® easyMAG® (bioMerieux) belonged to the second generation of automated extraction platforms based on silica extraction technology, and replaced the first-generation NucliSENS® miniMAG®. NucliSENS® easyMAG® limited manual extraction steps (particularly washing) and could simultaneously extract up to 24 clinical specimens in one hour. Its performance on clinical whole blood, sputum, serum and throat swab specimens, and on quality controls for molecular diagnostics, was considered similar to or better than that of other manual and automated NA extraction platforms [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. However, the extraction procedure was not fully automated: sample loading, homogenization of the lysed sample with silica, and recovery of eluted NA at the end of the process, all required human intervention. The third generation of the NucliSENS® miniMAG® and easyMAG® family, to be available in the last quarter of 2016, has been designed to fill these gaps. Based on the same extraction technology and using the same reagents and disposables as NucliSENS® easyMAG®, eMAG™ offers a significant gain in terms of automation, allowing simultaneous extraction of 48 samples directly from primary tubes, and distribution of NA extracts in PCR strips or tubes. It was first necessary to show that this gain in practicability did not undermine viral NA extraction performance by comparison with NucliSENS® easyMAG®.

2. Objective

The focus of this study was a comparative evaluation of the new eMAG™ and existing NucliSENS® easyMAG® extraction devices on clinical respiratory, whole blood, plasma and urine samples through qualitative and quantitative viral PCR analyses.

3. Study design

3.1. Study design

The evaluation was carried out in July 2016 in the clinical virology laboratory of Poitiers university hospital (France). Two hundred ninety-nine residual discard clinical samples submitted to the virology and mycobacteriology department for virological diagnosis from January 2014 to June 2016 were retrospectively selected for this evaluation. They consisted of respiratory samples (n = 199), whole blood (n = 50), EDTA plasma (n = 25) and urine (n = 25) specimens described in the next paragraph. All the samples had prospectively tested positive for at least one virus at the time of diagnosis, as part of standard-of-care orders by clinicians, and had then been stored at −80°C. Their minimal volume was 400 μL, allowing simultaneous extraction of identical volumes (200 μL) on the NucliSENS® easyMAG® and eMAG™ instruments, prior to real-time PCR and RT-PCR. The nucleic acids extracted from a given sample on the two platforms were amplified in the same run. The same thermocycler was used throughout the study. The samples were only tested for the initially diagnosed virus. Testing of respiratory samples also included cell control detection. The local IRB stated that ethical approval was not necessary for this research under French law.

3.2. Clinical specimens

The 199 respiratory samples selected for this study were nasal aspirations (n = 92), tracheal aspirations (n = 8), nasal swabs (n = 8), nasopharyngeal swabs (n = 87), nasal washes (n = 2) and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (n = 2) stored in viral transport medium. Routine viral testing using NucliSENS® easyMAG® (bioMerieux) extraction and Respiratory Multi Well System r-gene® (ARGENE®, bioMerieux) amplification identified 160 single-virus infections and 39 mixed viral infections, with a total of 49 rhinovirus/enterovirus (29 single-virus infections, 20 mixed viral infections), 32 influenza virus type B (27 single-virus infections, 5 mixed viral infections), 32 respiratory syncytial virus (26 single-virus infections, 6 mixed viral infections), 29 influenza A viruses (24 single-virus infections, 5 mixed viral infections), 25 human metapneumovirus (16 single-virus infections, 9 mixed viral infections), 22 coronavirus (12 single-virus infections, 10 mixed viral infections), 21 adenovirus (6 single-virus infections, 15 mixed viral infections), 17 bocavirus (10 single-virus infections, 7 mixed viral infections) and 15 parainfluenza virus (10 single-virus infections, 5 mixed viral infections). Fifty whole blood samples were also analyzed. Following easyMAG® extraction and respective R-gene® amplification kit analysis, respectively 22, 24 and 20 samples were found to be positive for cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human herpes virus type 6 (HHV6), with 34 single-virus infections (17 CMV, 8 EBV, 9 HHV6) and 16 mixed viral infections (11 EBV/HHV6, 5 CMV/EBV). Mean viral load ± one standard deviation (SD) in CMV, EBV and HHV6-positive samples was respectively 3.0 × 104 ± 1.12 × 105 (500–5.2 × 105 copies/mL), 1.05 × 104 ± 2.35 × 104 (46–1.1 × 105 copies/mL) and 1.38 × 103 ± 2.59 × 103 (23–9735 copies/mL). We also selected 25 plasma and 25 urine samples positive for BK virus (BKV) using easyMAG® extraction and BKV ELITe MGB® kit analysis (Elitech Group), with mean viral loads of respectively 4.30 × 104 ± 1.24 × 105 (2–5.7 × 105 copies/mL) and 4.59 × 108 ± 1.50 × 109 (392–6.0 × 109 copies/mL).

3.3. Nucleic acid extraction

Four hundred microliters of clinical sample were split into two 200 μL aliquots, which were extracted in parallel with the Nuclisens easyMAG® and eMAG™ instruments (bioMerieux) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The two extraction platforms use the same reagents and disposables. Respiratory specimens were distributed into 12-mL NucliSENS® Lysis Buffer Tubes containing 2 mL of lysis buffer, then submitted to “off-board” lysis for 10 min at room temperature before proceeding to the extraction step, whereas whole blood, plasma and urine samples were lysed “on-board” in 2 mL of lysis buffer. The 12-mL NucliSENS® Lysis Buffer Tubes (containing respiratory samples) and 2-mL cryogenic vials (Cryovial®, Simport) were directly positioned on the eMAG™ platform for extraction. Specific B was the extraction protocol used on both instruments, with 140 μL of magnetic silica for whole blood and 50 μL for respiratory, urine and plasma specimens. Nucleic acids were then recovered in 50 μL of elution buffer. Ten microliters of IC2 internal control were added to each whole blood, plasma and urine sample prior to extraction. Each extraction run contained one negative control.

3.4. Nucleic acid amplification

Nucleic acids extracted from respiratory samples were amplified with the Respiratory Multi Well System r-gene® kit (ARGENE®, bioMerieux) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. CMV, EBV, HHV6 and BKV viral load in whole blood, plasma and urine was quantified with the CMV R-gene®, EBV R-gene®, CMV HHV6,7,8 R-gene® and BK Virus R-gene® kits (ARGENE®, bioMerieux), respectively. Real-time PCR and RT-PCR reactions were performed on the ABI 7500 Fast device (Applied Biosystems).

3.5. Data presentation and analysis

Table 1 shows qualitative results (number of pathogens detected) obtained after extraction with the two platforms, for each kind of specimen. Viral load (mean and one SD) obtained after virus extraction from whole blood, plasma and urine with the two systems is indicated. Extraction efficiencies were compared by using Deming regression analysis of Ct values for qualitative analyses of respiratory samples (including both respiratory viruses and cell control detection), and of viral load values for quantitative analyses of whole blood, plasma and urine samples. Bland-Altman plots were used to depict differences between positive qualitative (Ct) and quantitative (viral load) results obtained with eMAG™ and easyMAG® [21]. Each point represents the observed difference between the results obtained with the two extraction methods against their mean. For quantitative analyses, horizontal lines corresponding to 0 ± 0.5 log10 and ±1 log10 were added as landmarks. All tables and graphs were generated with SAS 9.2 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Table 1.

Qualitative comparison and agreement percentages between NucliSENS® easyMAG® and eMAG™ nucleic acid extraction from respiratory, whole blood, plasma and urine samples.

| easyMAG® extraction |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Agreement | |||

| eMAG™ extraction | Respiratory | Positive | 415 | 8 | |

| Negative | 10 | 8 | 95.9% | ||

| Whole Blood | Positive | 52 | 5 | ||

| Negative | 5 | 3 | 84.6% | ||

| Plasma | Positive | 21 | 3 | ||

| Negative | 0 | 1 | 88% | ||

| Urine | Positive | 24 | 0 | ||

| Negative | 0 | 1 | 100% | ||

4. Results

4.1. Respiratory samples

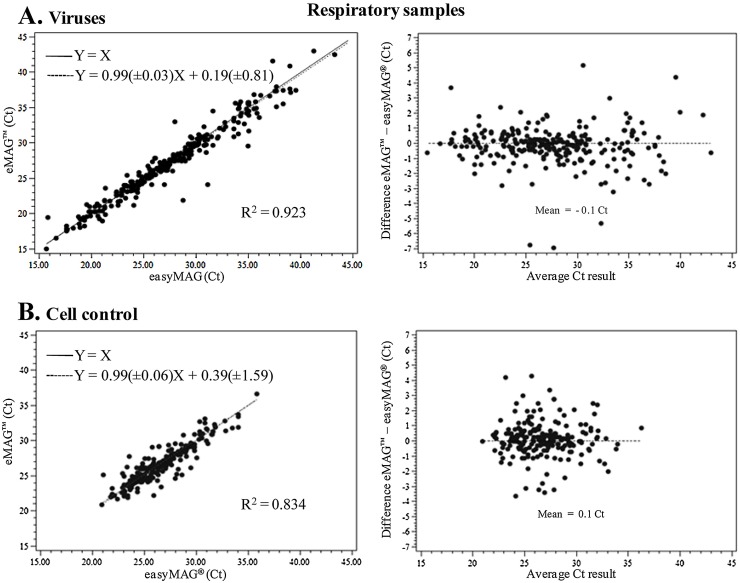

For the 199 respiratory samples extracted in parallel with NucliSENS® easyMAG® and eMAG™, data were collected for 441 amplification tests: 242 for respiratory viruses and 199 for the cell control. Overall agreement was 95.9% (423/441), with specific agreement of 93% (225/242) and 99.5% (198/199) for respiratory virus and cell control detection, respectively (Table 1). Eight samples positive at initial diagnosis were retrospectively found to be negative following both eMAG™ and easyMAG® extraction. The extraction of a sample volume of only 200 μL in this study, instead of the 400 μL prospectively tested on receipt of the respiratory specimens for virological diagnosis, is likely to explain this discrepancy. However, nucleic acid degradation during specimen storage cannot be ruled out either. Discrepant results between the two extraction platforms were well-balanced between eMAG™ (n = 10) and easyMAG® (n = 8). They corresponded to 9 respiratory viruses and 1 cell control not detected following eMAG™ extraction, and 8 respiratory viruses not detected after easyMAG® extraction. No significant association was found between these discrepancies and the nature of the viral nucleic acid (RNA or DNA), a specific virus species, single or multiple viral infections, or the type of respiratory sample (not shown). Ct values for discordant respiratory samples exceeded 33 (mean 35.6 ± 3) in all but one case (Ct 28.9 after easyMAG® extraction; not detected after eMAG™ extraction). Ct values obtained with eMAG™ and easyMAG® correlated well with an R2 of 0.923 for respiratory virus detection and 0.834 for the cell control (Fig. 1 ). The mean differences for individual respiratory virus detection between eMAG™ and easyMAG® (Fig. 1A, right side) ranged from −0.6 for influenza B virus to 0.8 Ct for bocavirus. It was 0.1 Ct for the cell control (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of the cycle threshold of respiratory virus (A) and cell control (B) detection after Nuclisens easyMAG® and eMAG™ extractions. (Left) Deming regression analysis of Ct values of samples positive with both extraction methods. The Deming regression curve equation and the correlation coefficient are indicated. The thin dotted line represents hypothetical identical performance between the two methods (Y = X), and the bold dotted line shows the actual correlation between the two methods; (right) Bland-Altman difference scatter plot for samples positive with both extraction methods.

4.2. Whole blood samples

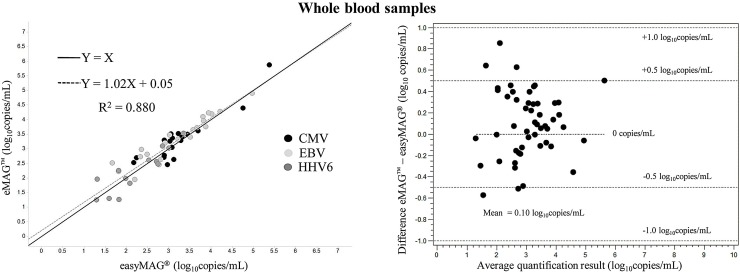

CMV, EBV and HHV6 targets were analyzed in 49 of the 50 samples, as extraction of one specimen was invalidated because of a system error on the eMAG™ platform. Qualitative and quantitative data analysis thus focused on 65 real-time quantitative PCR results, with an overall agreement of 84.6% (55/65) (Table 1). Ten discrepant results were observed, which were well-balanced between the 2 systems, as 5 samples (1 CMV, 1 EBV and 3 HHV6) that were positive after eMAG™ extraction were not detected with the easyMAG® system, and vice versa. The Ct values exceeded 37 for all but two of these samples, which were not detected with easyMAG® despite Ct values of 34.4 and 35.9 with eMAG™. The internal control was detected at the expected Ct value in both samples after easyMAG® extraction.

Mean CMV, EBV and HHV6 viral loads in whole blood were respectively 1.67 × 104 ± 5.48 × 104, 7.88 × 103 ± 1.98 × 104 and 4.46 × 102 ± 6.22 × 102 copies/mL with easyMAG®, and 4.26 × 104 ± 1.73 × 105, 9 × 103 ± 2 × 104 and 5.62 × 102 ± 9.42 × 102 copies/mL with eMAG™. The overall correlation coefficient between CMV, EBV and HHV6 viral loads was 0.880, with respective values of 0.839, 0.884 and 0.802. The differences between mean viral load obtained with eMAG™ versus easyMAG® were +0.08, +0.17 and +0.03 log10 copies/mL for CMV, EBV and HHV6, respectively. Forty-seven of the fifty-two differences between the results of the two extraction methods against their mean were below 0.5 log10 copies/mL (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of CMV, EBV and HHV6 viral load in 50 whole blood specimens after extraction with Nuclisens easyMAG® and eMAG™. (Left) Deming regression analysis of viral load (log10 copies/mL) in samples positive with both extraction methods. The Deming regression curve equation and the correlation coefficient are indicated. The solid line represents hypothetical identical performance between the two methods (Y = X), while the dotted line shows the actual correlation; (right) Bland-Altman difference scatter plot for samples positive by both extraction methods.

4.3. Plasma and urine samples

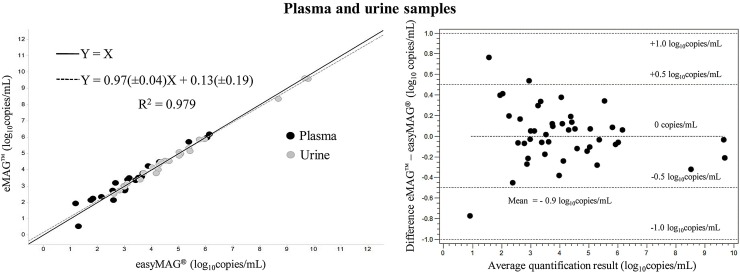

A total of 50 qualitative and quantitative real-time PCR results were available for BKV in the 25 plasma and 25 urine samples. Overall agreement was 94% (47/50), with no invalidated samples (Table 1). The three discrepant results were obtained with plasma samples, all in favor of eMAGTM and with Ct values always exceeding 41. Viral loads in the 45 samples positive with both extraction methods were then compared. Mean viral load in plasma was 1.12 × 105 ± 3.41 × 105 copies/mL with easyMAG® and 1.27 × 105 ± 3.68 × 105 copies/mL with eMAG™. Mean viral load in urine was 4.58 × 108 ± 1.5 × 109 and 3.4 × 108 ± 1.12 × 109 copies/mL, respectively. The overall correlation coefficient between easyMAG® and eMAG™ for BKV viral load was 0.979, with respective coefficients of 0.937 and 0.995 for plasma and urine. The difference between mean viral load was −0.2 and +0.1 log10 copies/mL for plasma and urine, respectively, with an average overall difference of +0.02 log10 copies/mL for the 45 results included in the analysis, in favor of eMAG™. Three differences between the results of the two extraction methods against their mean exceeded 0.5 log10 copies/mL, and all concerned plasma samples (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of BKV viral load in 25 plasma and 25 urine samples after extraction with Nuclisens easyMAG® and eMAG™. (Left) Deming regression analysis of viral load (log10 copies/mL) in samples positive with both extraction methods. The Deming regression curve equation and the correlation coefficient are indicated. The solid line represents hypothetical identical performance between the 2 methods (Y = X), while the dotted line shows the actual correlation; (right) Bland-Altman difference scatter plot for samples positive with both extraction methods.

5. Discussion

We report the first evaluation of eMAG™, the latest automated nucleic acid extraction platform from bioMerieux. Its performance was compared, using various clinical specimens, to that of its predecessor, easyMAG®, which has been thoroughly evaluated [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. Our study included about three hundred clinical samples consisting mainly of respiratory specimens but also of whole blood, plasma and urine. The results were assessed for qualitative targets consisting of respiratory viruses, in both single-virus and mixed viral samples (plus cell control detection), as well as quantitative targets, represented by CMV, EBV, HHV6 and BKV viral load. We found good agreement on qualitative results, ranging from 84.6% for whole blood to 95.9% for respiratory samples. Fourteen false-negative results were assessed following eMAG™ extraction of 9 respiratory samples and 5 whole blood specimens (1 CMV, 1 EBV and 3 HHV6). However, based on the equal number of false-negatives between the two platforms as well as on the Ct values of the discrepant results, most of the time higher than 35 cycles, it is very likely that there is no difference in extraction efficiency between easyMAG® and eMAG™ and that the discrepant results reflected target-load of the samples around the limit of detection leading to a stochastical chance on detection. Regarding the clinical relevance of the missed positive samples, they involved respiratory viruses other than influenza and thus would not have led to a delay or lack of treatment by neuraminidase inhibitor. For herpesviruses, the viral loads were low, with Ct values >37 Ct, and would likely have had no effect on therapeutic management in closely monitored patients. In quantitative terms, a good correlation of viral loads was also found, with R2 ranging from 0.802 to 0.995. Average overall differences between eMAG™ and easyMAG® were less than 0.10 log10 copies/mL. These results allowed us to conclude that, in our hands, the two platforms have comparable performance, whether on respiratory, whole blood, plasma or urine specimens.

These findings were largely expected, as eMAG™ and easyMAG® share the same silica extraction technology, but a comparative analysis was necessary because the new eMAG™ extraction platform is significantly more automated than its predecessor. Interestingly, the mean CMV, EBV and HHV6 viral loads measured in whole blood all favored eMAG™ (0.10 log10 copies/mL). This suggests more efficient DNA extraction from whole blood with eMAG™ than with easyMAG®; indeed, by comparison with other specimens, whole blood sample extraction is reported to require a larger volume of silica and lysis buffer on the easyMAG® platform [14]. This finding must, however, be confirmed in further studies using a larger number of whole blood samples.

The new eMAG™ platform uses the same reagents, disposables and protocols (specific B in our study) as easyMAG®, but it is far more practical. The eMAG™ manages NA extraction directly from primary sample tubes (from 1.5 to 14 mL), thereby avoiding the need for manual distribution in sample vessels, which is time-consuming and a source of error. It is then to take into account a dead volume of 50–245 μL, depending on the size and shape of the input tube, and this may be an issue with precious clinical samples such as cerebrospinal fluid and aqueous humor. Note that manual sample loading is still possible, even in tandem with automated loading in the same run. The eMAG™ also automatically distributes the internal control (IC2), which is necessary to check the extraction process and the absence of amplification inhibitors in the sample, and silica limiting again here hands-on time. Higher degree of automation of sample and reagent distribution would suppose a lower level of inter-run variation that was, however, not evaluated in the present work since the cell control does not allow this analysis and there are too few data with IC2. Finally, NA eluate transfer is possible in output tubes consisting of individual PCR tubes or strips from 0.2 to 2 mL. This new platform is thus likely to significantly reduce the sample processing time for PCR analysis, to improve the standardization and traceability of sample extraction, and to limit the risk of error through automatic distribution of clinical samples and reagents. However, it is noteworthy that extraction of one whole blood sample was invalidated on the eMAG™ platform during our study, because a precipitate formed when silica was added to the lysis buffer containing the specimen, preventing further sample handling by the instrument and leading to a system error. With the easyMAG® platform, the manual homogenization step allowed us to resuspend the precipitate, thereby enabling sample extraction. A similar issue might arise during automatic collection from a primary tube containing a non-homogeneous clinical sample such as viscous respiratory secretions or a blood sample containing a clot. It might be advisable to systematically transfer certain samples, such as bone marrow or distal respiratory specimens, to a secondary tube in order to ensure fluidity before positioning on the eMAG™ instrument.

Extraction throughput is doubled with eMAG™ compared to easyMAG®, as the eMAG™ platform consists of two independent sections each harboring 24 reactions, for a total of 48 simultaneous extractions. This makes eMAG™ advantageous for laboratories analyzing a large number of samples each day. Extraction takes 2 h with eMAG™, compared to about one hour with easyMAG®, but as eMAG™ is fully automated, working time can be spent on other tasks.

In conclusion, eMAG™ shows comparable performance to its predecessor, easyMAG®, on respiratory, whole blood, plasma and urine samples. Further evaluation, including other sample types such as biopsies and amniotic fluid, is necessary. Its more complete automation and higher throughput make the eMAG™ platform particularly suitable for laboratories performing large numbers of molecular analyses. The next step is to interface this new extraction platform with a PCR microplate dispenser.

Funding

NucliSENS® easyMAG® and eMAG™ consumables and R-gene® kits necessary for this evaluation were provided by bioMerieux France. However, the data obtained during eMAG™ evaluation were independently analyzed in the virology and mycobacteriology department of Poitiers University Hospital, which possesses the entire final data bank. BioMerieux had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Competing interests

None of the authors has any commercial or other association that might pose a conflict of interest (e.g., pharmaceutical stock ownership, consultancy).

Ethical approval

Not required.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Michèle Bonhumeau and Sylvie Gorel for their excellent technical assistance. We also thank Carine Zintilini, Raphaël Veyret, Véronique Ligeon and Philippe Bourgeois of bioMerieux for allowing us to evaluate eMAG™, and for their support throughout the study.

References

- 1.DeBiasi R.L., Kleinschmidt-DeMasters B.K., Weinberg A., Tyler K.L. Use of PCR for the diagnosis of herpesvirus infections of the central nervous system. J. Clin. Virol. 2002;25(Suppl. 1):S5–11. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(02)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Häusler M., Scheithauer S., Ritter K., Kleines M. Molecular diagnosis of Epstein–Barr virus. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2003;3:81–92. doi: 10.1586/14737159.3.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caliendo A.M. Multiplex PCR and emerging technologies for the detection of respiratory pathogens. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52(Suppl. 4):S326–330. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleines M., Scheithauer S., Schiefer J., Häusler M. Clinical application of viral cerebrospinal fluid PCR testing for diagnosis of central nervous system disorders: a retrospective 11-year experience. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014;80:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birnboim H.C., Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. (PMCID: PMC342324) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogelstein B., Gillespie D. Preparative and analytical purification of DNA from agarose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1979;76:615–619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.2.615. (PMCID: PMC382999) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang R., Lis J., Wu R. Elution of DNA from agarose gels after electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 1979;68:176–182. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)68012-6. (PMID: 232211) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marko M.A., Chipperfield R., Birnboim H.C. A procedure for the large-scale isolation of highly purified plasmid DNA using alkaline extraction and binding to glass powder. Anal. Biochem. 1982;121:382–387. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90497-3. (PMID: 6179438) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boom R., Sol C.J., Salimans M.M., Jansen C.L., Wertheim-van Dillen P.M., van der Noordaa J. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990;28:495–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. (0095-1137/90/030495-09$02.00/0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loens K., Bergs K., Ursi D., Goossens H., Ieven M. Evaluation of NucliSens easyMAG for automated nucleic acid extraction from various clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:421–425. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00894-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens W., Horsfield P., Scott L.E. Evaluation of the performance of the automated NucliSENS easyMAG and EasyQ systems versus the Roche AmpliPrep-AMPLICOR combination for high-throughput monitoring of human immunodeficiency virus load. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:1244–1249. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01540-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan K.H., Yam W.C., Pang C.M., Chan K.M., Lam S.Y., Lo K.F., Poon L.L., Peiris J.S. Comparison of the NucliSens easyMAG and Qiagen BioRobot 9604 nucleic acid extraction systems for detection of RNA and DNA respiratory viruses in nasopharyngeal aspirate samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46:2195–2199. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00315-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perandin F., Pollara P.C., Gargiulo F., Bonfanti C., Manca N. Performance evaluation of the automated NucliSens easyMAG nucleic acid extraction platform in comparison with QIAamp Mini kit from clinical specimens. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2009;64:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pillet S., Bourlet T., Pozzetto B. Comparative evaluation of a commercially available automated system for extraction of viral DNA from whole blood: application to monitoring of epstein-barr virus and cytomegalovirus load. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47:3753–3755. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01497-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim S., Park S.J., Namgoong S., Sung H., Kim M.N. Comparative evaluation of two automated systems for nucleic acid extraction of BK virus: NucliSens easyMAG versus BioRobot MDx. J. Virol. Methods. 2009;162:208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang G., Erdman D.E., Kodani M., Kools J., Bowen M.D., Fields B.S. Comparison of commercial systems for extraction of nucleic acids from DNA/RNA respiratory pathogens. J. Virol. Methods. 2011;171:195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Zanten E., Wisselink G.J., de Boer W., Stoll S., Alvarez R., Kooistra-Smid A.M. Comparison of the QIAsymphony automated nucleic acid extraction and PCR setup platforms with NucliSens easyMAG and Corbett CAS-1200 liquid handling station for the detection of enteric pathogens in fecal samples. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2011;84:335–340. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee A.V., Atkinson C., Manuel R.J., Clark D.A. Comparative evaluation of the QIAGEN QIAsymphony® SP system and bioMérieux NucliSens easyMAG automated extraction platforms in a clinical virology laboratory. J. Clin. Virol. 2011;52:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verheyen J., Kaiser R., Bozic M., Timmen-Wego M., Maier B.K., Kessler H.H. Extraction of viral nucleic acids: comparison of five automated nucleic acid extraction platforms. J. Clin. Virol. 2012;54:255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pillet S., Bourlet T., Pozzetto B. Comparative evaluation of the QIAsymphony RGQ system with the easyMAG/R-gene combination for the quantitation of cytomegalovirus DNA load in whole blood. Virol. J. 2012;9:231. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bland J.M., Altman D.G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]