Highlights

-

•

C. sinensis is one of the best known traditional Chinese medicine and health foods.

-

•

Polysaccharide (PS) is one of the richest groups and the main bioactive components.

-

•

PS exhibited various structural features and multiple bioactivities.

-

•

This review focused on production, extraction, structural features and bioactivities of PS.

Keywords: Cordyceps sinensis, Polysaccharide, Production, Extraction, Structural elucidation, Bioactivity

Abstract

Cordyceps (Ophiocordyceps sinensis) sinensis, the Chinese caterpillar fungus, is a unique and precious medicinal fungus in traditional Chinese medicine which has been used as a prestigious tonic and therapeutic herb in China for centuries. Polysaccharides are bioactive constituents of C. sinensis, exhibiting several activities such as immunomodulation, antitumour, antioxidant and hypoglycaemic. As natural C. sinensis fruiting body-caterpillar complexes are very rare and expensive, the polysaccharides documented over the last 15–20 years from this fungal species were mostly extracted from cultivated fungal mycelia (intracellular polysaccharides) or from mycelial fermentation broth (exopolysaccharides). Extraction and purification of the polysaccharides is a tedious process involving numerous steps of liquid and solid phase separations. Nevertheless, a large number of polysaccharide structures have been purified and elucidated. However, relationships between the structures and activities of these polysaccharides are not well established. This review provides a comprehensive summary of the most recent developments in various aspects (i.e., production, extraction, structure, and bioactivity) of the intracellular and exopolysaccharides from mycelial fermentation of C. sinensis fungi. The contents and data will serve as useful references for further investigation, production and application of these polysaccharides in functional foods and therapeutic agents.

1. Introduction

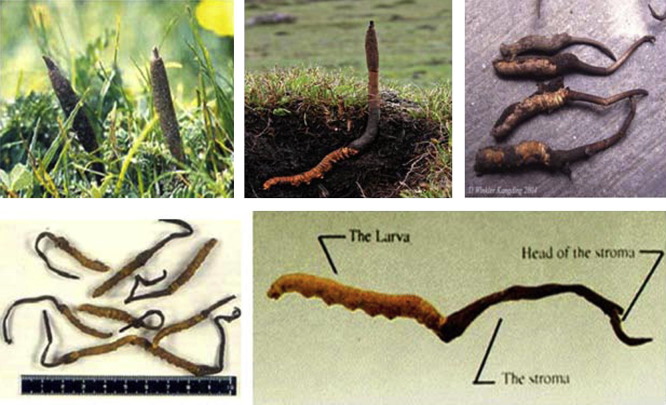

Cordyceps (Ophiocordyceps) sinensis (Berk.) Sacc., the Chinese caterpillar fungus or DongChongXiaCao (winter worm-summer grass) in Chinese or Tochukaso in Japanese, is a valuable medicinal fungus in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). C. sinensis is a parasitic fungus to the moth larvae (Lepidoptera) of Hepialus armoricanus (and Thitarodes). In late summer or early autumn, the larvae are infected by the fungal spores and gradually consumed by the fungal mycelia, and turned into “stiff worms” in winter. In spring and early summer of the following year, a stroma or fruiting body forms on the larva head, grows and emerges out of the ground like a grass (Fig. 1 ) (Chen et al., 2013, Holliday and Cleaver, 2008, Li and Tsim, 2004; Lo et al., 2013, Winkler, 2010, Zhang et al., 2012a, Zhu et al., 1998). The natural C. sinensis fruiting body-caterpillar complexes are mainly distributed on the high plateaus of 3500–5000 m above sea level in Tibet, Qinghai, Sichuan, and Yunnan Provinces in China (Li et al., 2011).

Fig. 1.

Cordyceps (Ophiocordyceps) sinensis fruiting body-caterpillar complexes: morphology and natural habitat (Paterson, 2008, Winkler, 2010).

C. sinensis has been used in China for more than 700 years, mainly as a tonic to invigorate the lungs and to nourish the kidneys (Dong & Yao, 2008). Modern pharmacological studies have shown its therapeutic effects on a wide range of diseases and conditions, such as respiratory, renal, liver, nervous system, and cardiovascular diseases, as well as tumours, aging, hyposexuality, and hyperlipidaemia (Ding et al., 2011, Ji et al., 2009, Liu et al., 2010, Lo et al., 2013, Marchbank et al., 2011, Song et al., 2010, Yue et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2011, Zhu et al., 1998). C. sinensis has been listed as an herbal drug in the official Chinese Pharmacopoeia by the Committee of Pharmacopoeia and Chinese Ministry of Health since 1964. During the outbreak of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in China in 2003, there was a notable increase in the use of C. sinensis. Over the last 10 years, the demand as well as the price for C. sinensis has increased dramatically in China, Japan, Korea and India (Au et al., 2012, Jeffrey, 2012, Winkler, 2009). As natural C. sinensis are very limited and cannot meet the increasing demand, fermentation technology has been widely exploited for large-scale production of C. sinensis fungal mycelia and other useful constituents. The fermentation-cultivated mycelia of some fungal strains isolated from the natural C. sinensis have been shown to produce the similar pharmacological efficacy to the wild fungal materials and been widely applied to various health food products (Zhu et al., 1998).

The multiple pharmacological effects of C. sinensis can be attributed to its chemical ingredients, including polysaccharides, proteins, nucleotides, mannitol, ergosterol, aminophenol, fatty acids, and trace elements. Actually, several reviews on these compounds and their properties and bioactivities of C. sinensis have been published in the last few years (Chen et al., 2013, Paterson, 2008, Shashidhar et al., 2013, Zhao et al., 2013, Zhong et al., 2009). In particular, polysaccharides represent one of the most abundant components in the fungus and a major group of bioactive constituents which have been extracted and isolated from the fruiting bodies, cultured mycelium, and fermentation broth, which are structurally diverse biomacromolecules with various physiochemical properties. Polysaccharides have been the target for the development and quality control of C. sinensis health products. More recently, some reviews on extraction, isolation, structure and bioactivities of polysaccharides from C. sinensis have appeared (Lo et al., 2013, Nie et al., 2013, Xiao, 2008, Zhong et al., 2009). However, these reviews mainly focus on separation techniques, structural features and bioactivities of intracellular polysaccharides (IPSs) from the fruiting body of natural C. sinensis and mycelia of cultured C. sinensis, but the mycelial fermentation, physicochemical properties and pharmacological activities of extracellular polysaccharides or exopolysaccharides (EPSs) isolated from culture broth of C. sinensis are less involved. In addition, the relationships are still not well established between the molecular structure and the bioactivity of C. sinensis derived polysaccharides. Herein, this review summarizes and compares the recent studies on the production, extraction, and purification of IPSs and EPSs from C. sinensis as well as the characterization of their structural features, chain conformations, and bioactivities.

2. Production of biomass and polysaccharides by mycelial fermentation

Wild or natural C. sinensis is becoming increasingly scarce because of reckless harvesting, geographical limitation, and unfavourable weather conditions for its proliferation (Yao, 2004). Cultivation of fungal mycelia is a more reliable alternative for mass production of the fungal materials. Several species of fungi have been successfully isolated from the natural C. sinensis such as Paecilomyces sinensis, Cephalosporium sinensis, Tolypocladium sinensis, and Hirsutella sinensis (Yin & Tang, 1995). Some of these species have been cultivated in large quantities of mycelial biomass by fermentation technology. The fungal mycelia have been reported to exert similar pharmacological effects to those of wild C. sinensis species (Dong and Yao, 2008, Zhu et al., 1998).

To improve the efficiency and productivity of mycelial fermentation processes, many investigators have studied the effects of various process factors on the maximal production of mycelial biomass and EPSs and to optimize the fermentation conditions, such as medium composition, temperature, pH, and culture vessel (Hsieh et al., 2005, Kim and Yun, 2005, Liu and Wu, 2012). Table 1 provides a summary of the strains, culture conditions, mycelial biomass and EPS yields of C. sinensis which have been reported in the literature. The biomass and EPS yields varied in a wide range from 10 to 54 g/L, and <1.0 to >40 g/L with the fungal species and culture conditions, respectively. In particular, our group has previously demonstrated the optimization of submerged culture conditions for C. sinensis (Cs-HK1), such as temperature, initial pH, carbon and nitrogen levels, minerals, and surfactants (Tween 80) (Leung and Wu, 2007, Leung et al., 2006, Liu and Wu, 2012). However, the production of bioactive EPS by liquid fermentation of edible or medicinal fungi (e.g. C. sinensis) is still a new area of research without much industrial application. Thus, there is a need to enhance the EPS productivity through effective strategies of process intensification in the future.

Table 1.

Mycelial biomass and EPS production by mycelial fermentation of Cordyceps sinensis.

| Fungi source | Fermentation conditions |

Mycelial biomass (g/L) | EPS yield (g/L) | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium composition | Temperature (°C) | pH | Culture vessel | Period (days) | ||||

| C. sinensis CCRC36421 | Sucrose 6.17%, corn steep powder 0.5%, (NH4)2HPO4 0.5%, KH2PO4 0.15% (w/v) | 25 | 4.4 | 5-L Jar fermentor: agitation speed, 300 rpm | 7 | 3.2 | Hsu et al., 2002, Hsieh et al., 2005 | |

| C. sinensis | Sucrose 20, corn steep powder 25, CaCl2 0.78, MgSO4·7H2O 1.73 (g/L) | 20 | 4.0 | 5-L Stirred-tank fermenter: aeration rate,2 vvm; agitation speed,150 rpm | 16 | 20.9 | 4.1 | Kim and Yun (2005) |

| C. sinensis 762 | Sucrose 50, peptone 10, yeast extract 3 (g/L) | 18 | Rotary shaker at 150 rpm | 40 | 22.1 | Dong, and Yao (2005) | ||

| C. sinensis Cs-HK1 | Glucose 40, yeast extract 5, peptone 5, KH2PO4 1, MgSO4·7H2O 0.5 (g/L);NH4Cl 10 mmol/L | 22–25 | Shaking incubator at 150 rpm | 7 | 23.2 | 3.4 | Leung et al., 2006, Leung and Wu, 2007 | |

| C. sinensis 16 | Sucrose 2%, yeast extract 0.9%, K2HPO4 0.3%,CaCl2 0.4% (w/v) | 25 | Rotary shaker at 150 rpm | 5 | 54.0 | 28.4 | Cha et al., 2007 | |

| C. sinensis 1 | Sucrose 3%, corn steep powder 5%, bean cake 4%, KH2PO4 0.1, MgSO4·7H2O 0.05%, vitamin B1 0.01% | 22 | 6.5 | Rotary shaker at 120 rpm | 7 | 5.9 | Quan, Wang, Du, and Liu (2007) | |

| C. sinensis 383 | Glucose 30, bean cake 20, MgSO4 2.0, KH2PO4 4.0 (g/L) | 24 | 7.0 | Rotary shaker at 140 rpm | 5 | 3.9 | Lang, Qi, Hou, Zhao, and Jiang (2009) | |

| C. sinensis | Sucrose 20, yeast extract 2.0, KH2PO4 1.0, MgSO4·7H2O 0.6 (g/L) | 26 | 7.0 | 1000-mL shake flask: aeration rate 1 L/min, agitation speed 130 rpm | 4 | 12.3 | 24.5 | Wu, Chen, and Hao (2009) |

| C. sinensis CCRC36421 | Rice bran 1.5%, molasses 0.5%, CSL 3%, KH2PO4 0.1%, MgSO4 0.05% | 25 | 5.5 | 5-L jar fermenter: aeration rate 1.0 vvm, agitation speed, 150 rpm | 5–6 | 48.9 | Choi et al (2010) | |

| Hirsutella sinensis | Potato extract 20%, sucrose 2.5%, peptone 0.5%, K2HPO4 0.2%, MgSO4 0.05% (w/v) | 24 | 5.5 | Rotary shaker at 180 rpm | 4 | 10.0 | 2.2 | Li, Jiang, and Guan (2010) |

| C. sinensis CS001 | Glucose 30, yeast extract 3, peptone 2, KH2PO4 0.6, MgSO4·7H2O 0.4, vitamin B1 0.01, palmitic acid 1.0 (g/L) | 27 | 6.5 | 250-mL shake flask at 160 rpm | 7 | 0.4 | Wang, Liu, Zhu, & Kuang, 2011 | |

| C. sinensis Cs-HK1 | Glucose 40, yeast extract 15, peptone 5, KH2PO4 1, MgSO4·7H2O 0.5 (g/L);NH4Cl 10 mmol/L; Tween 80 1.5% (w/v) | 25 | 6 | Shaking incubator at 150 rpm | 7 | 14.7 | 7.2 | Liu and Wu (2012) |

| C. sinensis | Glucose 30, peptone 15, KH2PO4 3.0, MgSO4·7H2O 1.5, potato 200 (g/L) | 250-mL shake flask | 25.0 | 2.8 | Yin, Qiao, Qin, Tang, and Jia (2013) | |||

3. Extraction, isolation and purification of polysaccharides

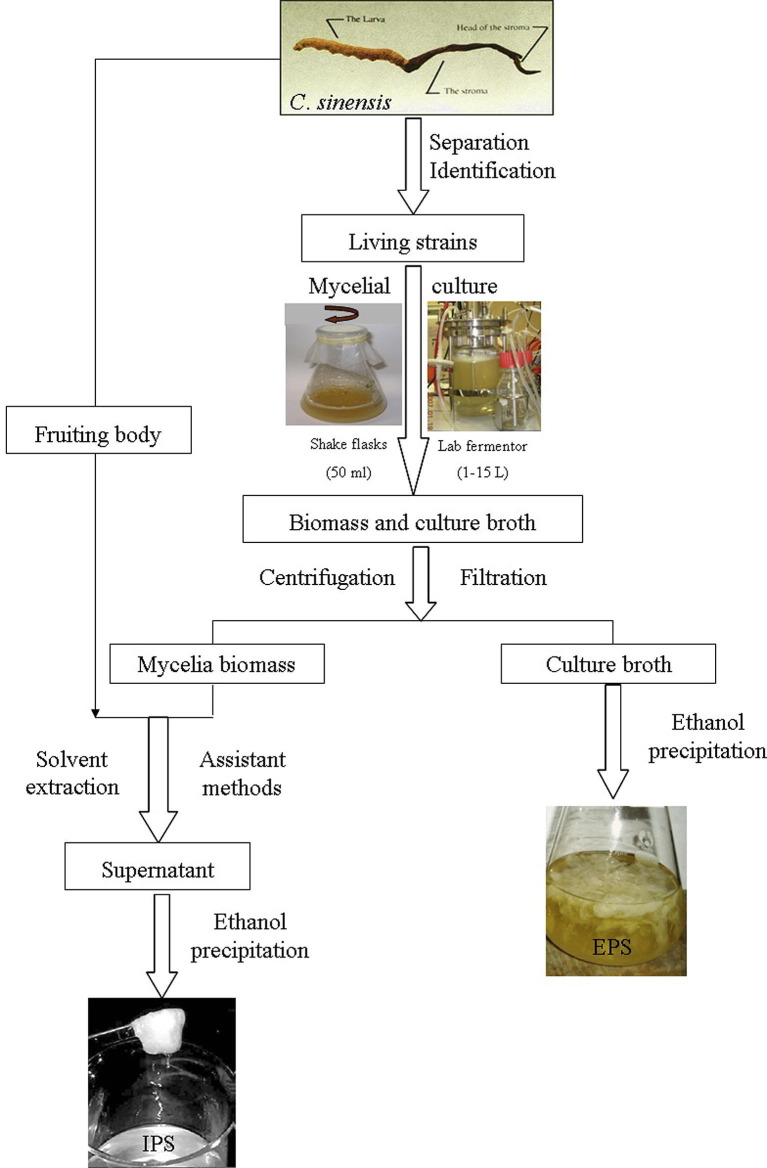

C. sinensis polysaccharides can be classified into two types according to their locations in the fungal cells, intracellular polysaccharides (IPSs) and extracellular polysaccharides (exopolysaccharides, EPSs). IPSs are extracted from the fruiting body (or worm) and mycelium of C. sinensis with pure water, aqueous acidic/alkaline solutions, aqueous buffers under heating (Guan et al., 2011, Kiho et al., 1999, Kiho et al., 1986, Kiho et al., 1996, Wang et al., 2009, Wu et al., 2007, Wu et al., 2005, Wu et al., 2005, Wu et al., 2006, Wu et al., 2006, Yan et al., 2011). Extraction in hot or boiling water is the most common and convenient method for extracting water-soluble mushroom polysaccharides. However, the major drawbacks of hot water extraction are the high extraction temperature, long extraction time and low extraction efficiency. Various methods have been used to improve the extraction efficiency such as treatment with enzymes, microwave and high power ultrasound (Wang et al., 2011, Xie et al., 2009). The application of high-power or high-intensity ultrasound or ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) has been widely studied for extracting polysaccharides from different plant materials. The enhancement of extraction efficiency by UAE is mainly attributed to the mechanical effects of ultrasound, particularly the shear forces arising from acoustic cavitation (Velickovic, Milenovic, Ristic, & Veljkovic, 2006). On the other hand, for extraction of EPSs, the fermentation broth of C. sinensis was sequentially centrifuged and concentrated, and the resultant material was precipitated by using ethanol, and then centrifuged to harvest the crude EPSs. Fig. 2 summarizes the isolation procedures of IPSs and EPSs from C. sinensis.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram for the extraction of intracellular and extracellular polysaccharides from Cordyceps sinensis.

After extracting crude polysaccharides from C. sinensis, the obtained polysaccharide precipitate was partially purified by deproteination and decoloration, and then further purified through column chromatography, such as ion-exchange chromatography, gel filtration chromatograph and affinity chromatography. Elution was conducted with an appropriate running buffer, followed by collection, concentration, dialysis, and lyophilization (Li et al., 2002, Li et al., 2003, Wang et al., 2011, Wang et al., 2009, Wu et al., 2005, Wu et al., 2006, Wu et al., 2007, Yan et al., 2010, Yan et al., 2011). In addition, based on the different solubility of polysaccharides in ethanol, isopropanol, and other solvents, polysaccharides were simply and effectively fractionated. Huang, Siu, Wang, Cheung, and Wu (2013) recently isolated EPS fractions from a fermentation medium of C. sinensis by gradient ethanol precipitation. Their results suggest that the method is simple and workable for the initial fractionation of polysaccharides, proteins, and their complexes with different molecular sizes and for further identification of bioactive components.

4. Physicochemical characterization

The physicochemical and structural features of a polysaccharide mainly include monosaccharide composition, molecular weight (MW), configuration of glycosidic linkages, type of glycosidic linkage, position of glycosidic linkage, sequence of monosaccharide, number and location of appended non-carbohydrate groups, and molecular chain conformation (Cui, 2005, Nie and Xie, 2011, Zhang et al., 2007). Polysaccharides with different monosaccharide constituents and chemical structures have been isolated from wild or cultured C. sinensis. Many research groups have elucidated the chemical structures of purified IPSs and EPSs using infrared spectroscopy, liquid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (one and two dimensions), solid-state NMR, gas chromatography (GC), GC-mass spectroscopy (GC–MS), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), acid hydrolysis, methylation analysis, periodate- oxidation, and Smith degradation (Akaki et al., 2009, Kiho et al., 1993, Kiho et al., 1996, Kiho et al., 1999, Nie et al., 2011, Wang et al., 2009, Wang et al., 2009, Wang et al., 2011, Wu et al., 2005, Wu et al., 2005, Wu et al., 2007, Yan et al., 2010, Yan et al., 2011). A wide range of bioactive polysaccharides of different structural characteristics from C. sinensis have been investigated based on differences in source materials, isolation protocols, and fractionation protocols. The sources, molecular properties, chemical structures, and bioactivities are summarized in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Polysaccharides originated from Cordyceps sinensis fungi: source, chemical structures and bioactivities.

| Living strains | Polysaccharides source | Extraction medium | Components | Molecular weight | Linkages and types | Bioactivities | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paecilomyces sinensis(Cs-4) | Mycelium | Hot water | Man:Gal = 1:1 | – | CS-I Galactomannan | – | Miyazaki et al. (1977) |

| Paecilomyces sinensis(Cs-4) | Mycelium | 5% Sodium carbonate | Man:Gal = 3:5 | 23 kDa | CT-4 N Galactomannan | – | Kiho et al., 1986 |

| Paecilomyces sinensis(Cs-4) | Mycelium | Hot water | Gal:Glc:Man = 62:28:10 | 45 kDa | CS-F30 | Hypoglycemic activity | Kiho et al., 1993, Kiho et al., 1996 |

| Paecilomyces sinensis(Cs-4) | Mycelium | Hot water | Gal:Glu:Man = 43:33:24 | 15 kDa | CS-F10 Galactoglucomann | Hypoglycemic activity | Kiho et al., 1999 |

| Cephalosporium sinensis Chen sp. nov. | Mycelium | Hot water | Glu:Man:Gal = 1:0.6:0.75 | 210 kDa | CSP-1 | Antioxidant activity; Hypoglycemic activity | Li et al., 2003, Li et al., 2006 |

| Paecilomyces sinensis(Cs-4) | Mycelium | Hot water | β-Glu | 13.6 kDa | Neutral (1 → 3),(1 → 4)-β-d- -glucan | – | Wu et al. (2005) |

| Paecilomyces sinensis(Cs-4) | Mycelium | Hot water | β-Glu | 12.9 kDa | (1 → 3)-β-d-glucan Cordyglucans | Antitumour activity | Wu et al. (2005) |

| Paecilomyces sinensis(Cs-4) | Mycelium | 0.05 M phosphate buffer | α-Glu | 184 kDa | SCI-I | – | Wu et al. (2005) |

| Paecilomyces sinensis(Cs-4) | Mycelium | 0.05 M acetate buffer | Glu:Man = 9:1 | 7.7 kDa | Mannoglucan | Antitumour activity | Wu et al. (2007) |

| Paecilomyces sinensis(Cs-4) | Mycelium | Hot water | Glc:Man:Gal = 21:2:1 | – | CS-Pp 1,3-β-d-glucan with 1,6-branched chain | Immunomodulating | Akaki et al. (2009) |

| Paecilomyces sinensis(Cs-4) | Mycelium | Hot water | Glc:Man:Gal = 2:1:1 | 460 kDa | → 3-α-d-Glcp-1 → 3-β-d- Glcp-1 → 3-β-d-Galp-1 → | Cholesterol esterase inhibitory activity | Kim (2010) |

| Cephalosporium sinense Chen | Mycelium | Hot water | Glc:Man:Gal = 2.8:2.9:1 | 8.1 kDa | CPS1 Glucomannogalactan | Antioxidant activity | Wang et al. (2009) |

| Cephalosporium sinense Chen | Mycelium | Hot water | Man, Glu, Gal, Uronic acid | 27 kDa | CAPS | Immunomodulating | Wang et al. (2009) |

| Cephalosporium sinense Chen | Mycelium | Hot water | Man:Glu: Gal = 4:11:1 | 43.9 kDa | Galactoglucomanno- -glycan (CPS-2) | Protection of chronic renal failure | Wang et al. (2010) |

| Tolypocladium sinensis | Mycelium | Hot water | α-Glu | 1180 kDa | WIPS α-d-(1 → 4)-glucan | Antitumour and Immuno-stimulating effects | Yan et al. (2011) |

| Tolypocladium sinensis | Mycelium | 1.25 M NaOH / 0.04% NaBH4 | α-Glu | 1150 kDa | AIPS α-d-(1 → 4)-glucan (86%), (1 → 6) -α-d-glucose (14%) | Antitumour and Immuno-stimulating effects | Yan et al. (2011) |

| Tolypocladium sinensis | Mycelium | Hot water | Man:Glu:Gal = 3.3:2.3:1 | – | APS | Antioxidant activity | Shen et al. (2011) |

| Paecilomyces sinensis(Cs-4) | Mycelium | Hot water | Glu(95%), Man, Gal | 260 kDa | CBHP α-1,4-linked-Glcp | Antifibrotic effect | Nie et al., 2011, Zhang et al., 2012a, Zhang et al., 2012b |

| Cordyceps ophioglossoides | Culture filtrate | Ethanol | β-Glu | 632 kDa | CO-1 | Antitumour activity | Yamada et al., 1984 |

| Paecilomyces sinensis(Cs-4) | Culture broth | Ethanol | Man:Gal:Glc = 10.3:3.6:1 | 43 kDa | CS-81002 | Immunomodulating | Gong et al., 1990 |

| Tolypocladium sinensis | Culture broth | 95% Ethanol | Man:Glu: Gal = 23:1:2.6 | 104 kDa | EPS | Immunomodulatory and antitumour | Yang et al., 2005, Chen et al., 2006, Sheng et al., 2011 |

| Paecilomyces sinensis | Culture broth | Ethanol | Glu:Man:Gal = 2.4:2:1 | 82 kDa | Cordysinocan | Immunomodulating | Cheung et al., 2009 |

| Tolypocladium sinensis | Culture broth | 95% Ethanol | Glu:Man:Gal = 15.2:3.6:1 | 40 kDa | EPS-1A | – | Yan et al. (2010) |

| Tolypocladium sinensis | Culture broth | Ethanol | Glcp:GlcUp = 8:1 | 36 kDa | AEPS-1 | Immunomodulating | Wang, Liu, Zhu, & Kuang, 2011 |

| Tolypocladium sinensis | Culture broth | Ethanol | ManNH2:GalNH2:Gal= 1.0:1.1:0.3 | 6 kDa | Poly-N-acetylhexosamine | Antioxidant activity | Chen, Siu et al. (2013) |

4.1. Monosaccharide composition

Monosaccharide composition analysis usually involves cleavage of glycosidic linkages by acid hydrolysis, derivatization, and detection and quantification by GC. In addition, high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection has been gradually developed to supplement traditional methods as it doesn’t require derivatization of monosaccharide with high resolution (Panagiotopoulos, Sempéré, Lafont, & Kerhervé, 2001). Recently, a 1-phenyl-3-methy-5-pyrazolone pre-column derivation method has been used to determine monosaccharide composition (Chen et al., 2013, Wang et al., 2010, Wang et al., 2009).

Although many different IPSs and EPSs have been obtained, the monosaccharide composition is usually glucose (Glu), mannose (Man), and galactose (Gal) in various mole ratios (Cha et al., 2007, Gong et al., 1990, Kiho et al., 1999, Li et al., 2003, Miyazaki et al., 1977, Nie et al., 2011, Wang et al., 2009, Wu et al., 2006, Yan et al., 2010). However, the IPSs are also found to only contain D-Glu to be composed of different polyglucans (Akaki et al., 2009, Wu et al., 2005, Wu et al., 2005, Wu et al., 2006, Yan et al., 2011), but so far, only one study has been reported that EPS isolated from culture broth of C. sinensis was a β-glucan (Yamada et al., 1984). In addition, IPSs and EPSs may also contain uronic acid, proteins and inorganic elements (Kiho et al., 1986, Wang et al., 2011, Wang et al., 2011). These polysaccharide conjugates isolated from natural or cultured C. sinensis also represent a major class of bioactive compounds and may exert more important pharmacological effects than neutral polysaccharides.

4.2. Average molecular weight

Various techniques such as viscometry, osmometry, sedimentation, and HPLC have been used to determine the average polymer molecular weight (MW) and polydispersity index. Among them, high-performance gel permeation chromatography (HPGPC) is a common method for determining the MW of polysaccharides and has also been used by many researchers for MW of IPSs and EPSs. Size-exclusion chromatography with multi-angle laser light scatter detection is also an efficient method for the evaluation of the absolute MW of polysaccharides and provides greater resolution than traditional gel permeation chromatography (Boukari et al., 2009, Hilliou et al., 2009). Different MWs ranging from ∼103 to ∼106 Da have been found in various source materials of C. sinensis and experimental conditions (Nie et al., 2013, Yan et al., 2011, Zhao et al., 2013, Zhong et al., 2009, Zhou et al., 2009).

4.3. Chemical structures

IPSs from natural and cultured C. sinensis usually consist of glucose, mannose, and galactose with 1 → 4(6)-glucopyranosyl (Glcp), 1 → 6-mannopyranosyl (Manp), and 1 → 4(6)-galactopyranosyl (Galp) (Guan et al., 2011, Nie et al., 2013, Zhong et al., 2009, Zhou et al., 2009). The earliest reports on IPSs by Miyazaki et al. (1977) and Kiho et al. (1986) included a galactomannan designated CS-I from a hot-water extract and a water-soluble, protein-containing galactomannan (CT-4N) isolated from a 5% sodium carbonate extract of C. sinensis, respectively. Both IPSs contained (1 → 2)-linked d-mannopyranosyl main-chains and (1 → 5)-linked d-galactofuranosyl side-chains. However, significant differences between CS-I and CT-4N were observed, i.e., CS-I contains (1 → 2,3) linkages of d-mannopyranose residues, as well as (1 → 3) and (1 → 6) linkages of galactofuranose, but CT-4 N has (1 → 4,6) linkages of mannopyranose and (1 → 6) linkages of galactopyranose. Thus, galactomannans from C. sinensis have a core of d-mannopyranosyl residues and d-galactofuranosyl side chains, and some differences in the linkage mode are observed. In addition, a galactoglucomannan named CS-F10 (Kiho et al., 1999) isolated from C. sinensis mycelium had a comb-type structure composed of non-reducing terminal α-d-glucopyranosyl residues, (1 → 5 and/or 6)-linked β-d-galactofuranosyl residues, as well as (1 → 2)-linked and branched α-d-mannopyranosyl residues. Recently, some water-soluble IPSs isolated from the cultured C. sinensis have been identified as glucomannogalactans, whose backbone were mainly composed of (1 → 2) and (1 → 4)-linkage of mannose, (1 → 3)-linkage of galactose, (1 → ), and (1 → 3,6)-linkage of glucose (Nie et al., 2011, Wang et al., 2009). Furthermore, a novel neutral mannoglucan isolated from C. sinensis mycelium has a backbone of predominantly (1 → 4)-linked α-d-Glcp (61.3%) together with a proportion of (1 → 3)-linked α-d-Glcp residues (28.0%), with single α-d-Manp units (10.7%) as the side chains attached to C-6 of (1 → 3)-linked d-Glcp residue (Wu et al., 2007). Similarly, Wang, Yin et al. (2010) reported the chemical structure of a water-soluble polysaccharide (CPS-2) isolated from cultured C. sinensis, which was composed mostly of a α-(1 → 4)-d-glucose and a α-(1 → 3)-d-mannose branched with α-(1 → 4,6)-d-glucose every twelve residues on average. Based on the above reports, it can be concluded that heteropolysaccharides are the most common bioactive polysaccharides in the fruiting bodies and mycelia of C. sinensis.

Some researchers have also reported that IPSs are polyglucans with different structural characteristics. For instance, Wu et al. (2005) found that cordyglucans obtained from C. sinensis mycelia is mainly composed of a (1 → 3)-β-d-glucan linked backbone with short (1 → 6)-β-d-glucan linked branches. Wu et al. (2006) also reported that the structure of a polysaccharide (SCP-I) isolated from C. sinensis mycelium, i.e., SCP-I, is a d-glucan containing an α-(1 → 4)-linked backbone and a branched short α-(1 → 6)-linkage. Furthermore, Akaki et al. (2009) reported that an insoluble polysaccharide (CS-Pp) purified from the cultured mycelium of C. sinensis was a 1,3-β-d-glucan with some 1,6-branched chains. Recently, Yan et al. (2011) isolated the two polysaccharides, WIPS and AIPS, from hot water and dilute alkaline extracts, respectively, of the mycelial biomass of a C. sinensis fungus Cs-HK1, which were characterized as α-d-glucans with a backbone of (1 → 4) linked α-d-glucopyranosyl (Glcp) (>60%). WIPS is found to have a short branch of (1 → 6)-linked α-d-Glcp (∼14%), whereas AIPS is a highly linear glucan.

In addition to the IPSs extracted from the mycelium or fruiting bodies of C. sinensis, EPSs isolated from the culture broth of C. sinensis have been reported. Gong et al. (1990) reported an EPS called CS-81002 isolated from the fermentation medium of C. sinensis and characterized as a branched heteropolysaccharide. Recently, Yan et al. (2010) reported the isolation and structure of EPS-1A from a fermentation broth of C. sinensis Cs-HK1. EPS-1A was found to be a slightly branched polysaccharide with its backbone being composed of (1 → 6)-α-d-glucose residues (∼77%) and (1 → 6)-α-d-mannose residues (∼23%). Branching occurred at the O-3 position of (1 → 6)-α-d-mannose residues of the backbone with (1 → 6)-α-d-mannose residues and (1 → 6)-α-d-glucose residues and terminated with β-d-galactose residues. Meanwhile, Wang, Peng et al. (2011) reported that on the acidic polysaccharide AEPS-1, which had a linear backbone of (1 → 3)-linked α-d-Glcp residues with two branches, namely, α-d-Glcp and α-d-pyrano-glucuronic acid (GlcUp), attached to the main chain by (1 → 6) glycosidic bonds at every seventh α-d-Glcp unit. In addition, a novel poly-N-acetylhexosamine (polyhexNAc) of about 6 kDa was isolated from the low-MW fraction of EPS produced from the liquid fermentation of C. sinensis Cs-HK1. The molecular structure was elucidated as a [-4-β-d-ManNAc-(1 → 3)-β-d-GalNAc-(1 → ] disaccharide repeating unit in the main chain with a Gal branch randomly occurring at the 3-position of ManNAc (Chen, Siu et al., 2013).

4.4. Conformational features

The activities of polysaccharides depend on their MWs, chemical structures, and chain conformations. In general, polysaccharides in aqueous solutions exhibit different forms of chain conformations, such as random coil (Senti et al., 1955), various helical forms, single helix, double helix, triple helix (Kashiwagi et al., 1981, Sato et al., 1984, Zhang and Yang, 1995), and aggregate (Ding, Jiang, Zhang, & Wu, 1998). A few reports are available on the solution properties and chain conformations of C. sinensis polysaccharides. For example, Cai, Li, and Lu (1999) firstly developed a method to study the morphology of a IPS by atomic force microscopy (AFM). Their results show that this IPS has a multi-branched structure and various linkages between adjacent monosaccharides, which make up small rings and helical structures. Very recently, the morphological characteristics and chain conformation of EPS isolated from a mycelial culture of C. sinensis Cs-HK1 have been analyzed by AFM together with the Congo red test, optical rotation, and dynamic light scattering. Results suggest that this EPS forms large interwoven networks in aqueous solution and is primarily connected with triple-helical conformation and occasionally single-helical conformation in solution. However, IPSs obtained from Cs-HK1 mycelium exhibit random coils in aqueous alkaline solutions (Wang et al., 2010, Wang et al., 2011, Yan et al., 2011). In addition, the random coils or aggregated networks of EPS-1 formed in aqueous solution were transformed into the single helices after sulfation (Yan, Wang, Ma, & Wu, 2013).

The relationships among solution properties, chain conformations of polysaccharides, and their biological activities are difficult to elucidate. The detailed chain conformations of C. sinensis polysaccharides in aqueous solutions require further investigations using other technological means, such as static and dynamic light scattering, viscosity analysis based on the theory of dilute polymer solutions, circular dichroism analysis, transmission electron microscope, scanning electron microscopy, AFM, AFM-based single-molecule force spectroscopy, fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, and NMR spectroscopy (Yang, & Zhang, 2009). Diluted solution theory, molecular modeling, and computer-assisted energy minimization methods have also been used to analyze the chain conformation of polysaccharides (Brant, 1981, Pol-Fachin et al., 2009, Pérez et al., 1996, Strlegel et al., 1999).

5. Bioactivities

Based on TCM theories, the major effects of C. sinensis are “to enrich the lung yin and yang”. Its use includes treatment of chronic lower back pain, sensitivity to cold, overabundance of mucus and tears, chronic cough and wheezing, and blood in phlegm due to consumption as a result of kidney yang (shenyangqu). C. sinensis also has antibacterial activity, reduces asthma, lowers blood pressure, and strengthens heartbeat according to Western medicine (Zhu et al., 1998). Polysaccharides represent a major class of bioactive constituents of C. sinensis, contributing to its health effects and pharmacological activities according to a large number of animal and clinical studies. The multiple bioactivities and health benefits of IPSs and EPSs are summarized and compared in detail below.

5.1. Immunomodulatory activity

Immunomodulation is the most notable biological function of natural polysaccharides, which is associated with their putative role as biological response modifiers (Moradali, Mostafavi, Ghods, & Hedjaroude, 2007). The immuno–stimulating and immunosuppressive properties of IPSs and EPSs have been assessed on natural killer cells, T-cells, B-cells, and macrophage-dependent immune system responses (Koh, Yu, Suh, Choi, & Ahn, 2002; Paterson, 2008, Zhong et al., 2009, Zhou et al., 2009). Phagocyte release is an early step in the response of macrophages to pathogen invasion of the human body. Macrophages can also defend against pathogen invasion by secreting proinflammatory cytokines [e.g., tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-1] and releasing cytotoxic and inflammatory molecules [e.g., nitric oxide (NO) and reactive oxygen species] (Medzhitov, & Janeway, 2000).

The majority of studies on IPSs and EPSs immunomodulation have been evaluated by activating macrophages. EPSs prepared from cultured C. sinensis induce the production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 dose-dependently and elevate phagocytes in monocytes and PMN, but IPSs only moderately induce TNF-α release, CD11b expression, and phagocytes at the same concentration (Cheung et al., 2009, Kuo et al., 2007). This finding indicates that the immunomodulatory components of cultured C. sinensis mainly reside in the culture filtrate and are similar to previously reported ones (Gong et al., 1990). Recent reports have shown that polysaccharides isolated from various natural or cultured C. sinensis have the same immunomodulatory activity of stimulation of the release of several major cytokines in the mouse macrophage cell line RAW264.7 and in mouse splenocyte cells by activating the IκB-NF-κB pathway (Akaki et al., 2009, Chen et al., 2010, Wang et al., 2011). More recently, Chen, Yuan, Wang, Song, and Zhang (2012) reported that an acid polysaccharide fraction (APSF) from C. sinensis fungus could increase the expressions of TNF-α, IL-12 and iNOS, and reduce the expression of IL-10 of Ana-1 cells, convert M2 macrophages to M1 phenotype by activating NF-κB pathway.

5.2. Antitumour activity

Since the first report on the antitumour activity of mushroom polysaccharides in the 1960s (Chihara, 1969), researchers have isolated structurally diverse polysaccharides with strong antitumour activity from plants, animals, and fungi. Mushroom polysaccharides exert inhibitory effects toward many kinds of tumours, such as Sarcoma 180 solid tumour, Ehrlich solid tumour, Sarcoma 37, Yoshida sarcoma, and Lewis lung carcinoma (Wasser, & Weis, 1999). The currently accepted mechanism by which mushroom polysaccharides exert antitumour effects can be summarized as follows: (1) prevention of oncogenesis by oral administration of polysaccharides isolated from medicinal mushrooms, (2) enhancement of immunity against bearing tumours, (3) direct antitumour activity to induce the apoptosis of tumour cells, and (4) prevention of the spread or migration of tumour cells in the body (Moradali et al., 2007, Wasser, 2002, Zhang et al., 2007).

Many studies have demonstrated that both of IPSs and EPSs have strong antitumour activity through the above proposed mechanisms. As a simple method, the prevention of the onset of tumour by oral administration is used to evaluate the antitumour activity of polysaccharides in vivo. IPSs obtained from the mycelia of C. sinensis are effective against sarcoma 180, with almost 90% inhibition in ICR/JCL mice (Wu et al., 2005, Zhang et al., 2007). In addition, EPSs obtained from a cultured broth of C. sinensis significantly lowers c-Myc, c-Fos, and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in B16 melanoma-bearing mice. Thus, EPSs can inhibit tumour growth in the lungs and liver of mice and can be a potential adjuvant in cancer therapy (Yang et al., 2005).

EPSs exert their antitumour effect mainly through the enhancement and activation of the immune response of the host organism. An EPS isolated from one of the anamorph strains of C. sinensis belonging to Tolypocladium spp. is found to significantly enhance the neutral red uptake capacity of peritoneal macrophages and spleen lymphocyte proliferation in B16-bearing mouse. The metastasis of B16 melanoma cells in lungs and liver is also significantly inhibited. Moreover, this EPS can markedly prevent H22 tumour growth and elevate immunocyte activity in H22 tumour-bearing mice, indicating that EPSs inhibit tumour cells mainly by activating the host’s immune system (Zhang et al., 2008, Zhang et al., 2005). To confirm this finding, Sheng, Chen, Li, and Zhang (2011) investigated the effects of EPSs on immunocytes in vitro, and results indicate that EPS treatment significantly promotes the mRNA and protein levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ. This phenomenon supports the assumption that antitumour activity is related to the promoted cytokine expression of immunocytes. EPSs can also stimulate the maturation and activation of murine and human dendritic cells by inhibiting STAT3 activation (Huang et al., 2011, Song et al., 2011). Furthermore, EPS may induce dendritic cell sarcoma (DCS) cells to exhibit mature characteristics, and the mechanism involved is probably related to the inhibition of the JAK2/STAT3 signal pathway and promotion of the NF-κB signal pathway (Song et al., 2013). On the other hand, IPSs can also activate many immune cells to modulate the release of cell signal messengers such as cytokines, and increased cytokine production in immune cells has been studied in mice and humans (Chen et al., 1997, Yoon et al., 2008).

Finally, the ability to induce apoptosis has been identified and utilized in successful cancer chemotherapeutics (Chen et al., 1997, Yoon et al., 2008), and studies have suggested that C. sinensis can induce apoptosis (Buenz, Bauer, Osmundson, & Motley, 2005). A 410 kDa polysaccharide fraction (IPS) isolated from C. sinensis is found to inhibit cell proliferation, promote the apoptosis of IL-1- and platelet-derived growth factor-BB-activated human mesangial cells in vitro, and prevent the tyrosine phosphorylation of human mesangial proteins. Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL are probably among these proteins as revealed by results of immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting (Yang et al., 1999, Yang et al., 2003). Similarly, crude polysaccharides obtained from mycelium of C. sinensis also affect the induction of apoptosis and expression of p53 gene in SP2/0 cells in vitro (Liu et al., 2009). Shen, Shao, Ni, Xu, and Tong (2009) reported the effects of the polysaccharide fraction of C. sinensis (PSCS) on triptolide (TPL)-induced apoptosis in HL-60 cells and the molecular events and signaling pathway, enhancing TPL-induced apoptosis and inhibiting the expression of NF-κB and caspases 3, 6, 7, and 9. However, up to now, no studies revealed that EPSs isolated from culture broth of C. sinensis could induce apoptosis.

5.3. Antioxidant activity

Oxidation phenomena have been implicated in many illnesses, such as diabetes mellitus, arteriosclerosis, nephritis, Alzheimer’s disease, and cancer (Negre-Salvayre, Coatrieux, Ingueneau, & Salvayre, 2008). Therefore, natural antioxidants isolated from plants, fungi, and marine algae represent most useful nutraceuticals and functional foods for health protection and disease prevention (Gutteridge, & Halliwell, 1994). Antioxidant activity has become one of the focuses of studies on mechanisms of the nutraceutical and therapeutical effects of TCM using various assay methods and activity indices (Dong and Yao, 2008, Schlesier et al., 2002).

Li, Li, Dong, and Tsim (2001) studied the antioxidative activity of water extracts of natural C. sinensis and mycelial biomass of the Cordyceps anamorph fungus Cephalosporium sinensis of various sources using xanthine oxidase, haemolysis induction, and lipid peroxidation. Their results show that Cordyceps generally possesses strong antioxidative activity in all assays, and cultured Cordyceps mycelia have antioxidative activity as strong as that of natural C. sinensis. Further testing suggests that several forms of IPSs prepared by ethanol precipitation and DEAE column chromatography have great antioxidative activities. Li et al. (2003) used column chromatography to purify a polysaccharide-enriched fraction isolated from cultured C. sinensis that possesses strong oxidative activity. A polysaccharide named CSP-1 is then obtained using activity-guided fractionation. CSP-1 with a MW of 210 kDa is found to have strong antioxidative activity in rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells, protecting against H2O2-induced cell damage, lipid peroxidation, and activation of major antioxidant enzymes, including glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase in cells. Very recently, an APS has been isolated from Tolypocladium sinensis, another anamorph strain of C. sinensis. This APS is found to markedly protect PC12 cells from H2O2-induced cell injury by increasing glutathione peroxidase, catalase, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activities, as well as by reducing lactate dehydrogenase and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels (Shen, Song, Wu, & Zhang, 2011). In addition, IPSs also affect the antioxidative activity of H22-bearing mice by enhancing the SOD activity of the liver, brain, and serum, as well as the GSH-Px activity of the liver and brain in tumour-bearing mice, and by reducing the MDA level in the liver and brain of tumour-bearing mice (Chen et al., 2006).

A few studies have reported on the antioxidative activities of EPSs isolated from culture broths of C. sinensis. Wu et al. recently studied the antioxidant action of an EPS (named Cs-HK1) isolated from the mycelial liquid culture of C. sinensis fungus by ethanol precipitation in vitro. Results demonstrate that Cs-HK1 shows moderate antioxidative activities, and acidic degradation can improve its antioxidative activities and radical-scavenging capacities (Leung et al., 2009, Yan et al., 2009). Very recently, EPS fractions were isolated from the fermentation broth of Cs-HK1 by gradient precipitation with ethanol at different volume ratios to the liquid medium exhibited moderate antioxidant activities and their activities showed a significant dependence on the protein content (Huang et al., 2013).

5.4. Hypoglycemic effect

Many research groups have evaluated the hypoglycaemic effects of natural products, including fungal polysaccharides using the Streptozotocin (STZ)-induced and alloxan-induced animal models (Hwang and Yun, 2010, Hwang et al., 2005; Yamac et al., 2008). IPSs extracted with hot water and alkalis have significant hypoglycemic effects on normal and alloxan-diabetic mice and STZ-diabetic rats in vivo by reducing the plasma glucose level in both STZ-induced diabetic rats and alloxan-induced diabetic mice, thereby increasing the serum insulin levels in diabetic animals (Li et al., 2006, Wang and Shiao, 2000, Zhang et al., 2006). IPSs also significantly lowered the levels of plasma triglyceride and cholesterol in mice and increase the activities of hepatic glucokinase, hexokinase, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Kiho et al., 1993, Kiho et al., 1996, Kiho et al., 1999).

5.5. Other bioactivities

As aforementioned, IPSs and EPSs obtained from wild or cultured C. sinensis demonstrate immunoregulation, antitumour, antioxidation, and hypoglycemic effects, as well as other important bioactivities, including anti-fibrosis, anti-fatigue, kidney protection, increasing plasma testosterone levels, and radiation protection (Nie et al., 2013, Wang et al., 2009, Wang et al., 2010, Wong et al., 2011, Yan et al., 2012, Yao et al., 2014, Zhang et al., 2012b, Zhong et al., 2009).

6. Conclusions and future perspectives

C. sinensis is a well-known and precious medicinal fungus in China for its ability to treat a broad spectrum of human diseases, especially those related to the functions of the lung and kidney, the immune system, and for its ability to enhance the quality of life and physical performance. Polysaccharides have been identified as the major active components of C. sinensis with a wide range of bioactivities including immunomodulation, antitumour, antioxidation, and hypoglycemic effects. Fermentation production, isolation, structural characterization, and the bioactivities of polysaccharides from different wild or natural C. sinensis have been extensively investigated in recent years, mainly in China, Japan, and Korea. However, the relationship between structural features, solution behavior, space conformation, and their bioactivity is unclear due to the structural diversity and complexity of polysaccharide molecules. The fruiting bodies or mycelial biomass as the sources of IPSs, especially EPSs isolated from the culture broth, have attained from different C. sinensis species and in various conditions. Because of the variable properties of raw material and the composition of polysaccharides, it is difficult to maintain consistency, reproducibility and reliability of the results. There is a need to establish standard protocols for collection and preparation of the source material and for the extraction, isolation and purification of polysaccharides. These will be useful for determination of the chemical structures and chain conformations and the biological activities and for applications in food, medicine and cosmetic products.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants from the China’s Postdoctoral Science Fund Projects (2013M531292) and the Guangdong Education University-Industry Cooperation Project (2008B090500002).

Contributor Information

Jing-Kun Yan, Email: jkyan_27@163.com.

Jian-Yong Wu, Email: jian-yong.wu@polyu.edu.hk.

References

- Akaki J.J., Matsui Y., Kojima H., Nakajima S., Kamei K., Tamesada M. Structural analysis of monocyte activation constituents in cultured mycelia of Cordyceps sinensis. Fitoterapia. 2009;80:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au D., Wang L., Yang D., Mok D.K., Chan A.S., Xu H. Application of microscopy in authentication of valuable Chinese medicine I-Cordyceps sinensis, its counterfeits, and related products. Micro Research Technology. 2012;75:54–64. doi: 10.1002/jemt.21024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukari I., Putaux J.L., Cathala B., Barakat A., Saake B., Rémond C., O’Donohue M., Chabbert B. In vitro model assemblies to study the impact of lignin-carbohydrate interactions on the enzymatic conversion of xylan. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:2489–2498. doi: 10.1021/bm9004518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brant D.A. American Chemical Society; Division of Carbohydrate Chemistry: 1981. Solution properties of polysaccharides: Based on a symposium. [Google Scholar]

- Buenz E.J., Bauer B.A., Osmundson T.W., Motley T.J. The traditional Chinese medicine Cordyceps sinensis and its effects on apoptosis homeostasis. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2005;96:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L.T., Li P., Lu Z.H. Observation of the structure morphology of Cordyceps polysaccharide by atomic force microscope. Journal of Chinese Electron Microscopy Society. 1999;18:103–105. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cha S.H., Lim J.S., Yoon C.S., Koh J.H., Chang H.I., Kim S.W. Production of mycelia and exo-biopolymer from molasses by Cordyceps sinensis 16 in submerged culture. Bioresource Technology. 2007;98:165–168. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.J., Shiao M.S., Lee S.S., Wang S.Y. Effect of Cordyceps sinensis on the proliferation and differentiation of human leukemic U937 cells. Life Sciences. 1997;60:2349–2359. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Siu K.C., Wang W.Q., Liu X.X., Wu J.Y. Structure and antioxidant activity of a novel poly-N-acetylhexosamine produced by a medicinal fungus. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2013;94:332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P.X., Wang S., Nie S., Marcone M. Properties of Cordyceps sinensis: A review. Journal of Functional Foods. 2013;5:550–569. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2013.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Yuan F., Wang K., Song D., Zhang W. Modulatory effects of the acid polysaccharide fraction from one of anamorph of Cordyceps sinensis on Ana-1 cells. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;142:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.P., Zhang W.Y., Lu T.T., Li J., Zheng Y., Kong L.D. Morphological and genetic characterization of a cultivated Cordyceps sinensis fungus and its polysaccharide component possessing antioxidant property in H22 tumour-bearing mice. Life Sciences. 2006;78:2742–2748. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Zhang W., Shen W., Wang K. Effects of the acid polysaccharide fraction isolated from a cultivated Cordyceps sinensis on macrophages in vitro. Cellular Immunology. 2010;262:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung J.K.H., Li J., Cheung A.W.H., Zhu Y., Zheng K.Y.Z., Bi C.W.C., Duan R., Choi R.C.Y., Lau D.T.W., Dong T.T.X., Lau B.W.C., Tsim K.W.K. Cordysinocan, a polysaccharide isolated from cultured Cordyceps, activates immune responses in cultured T-lymphocytes and macrophages: Signaling cascade and induction of cytokines. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2009;124:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chihara G. The antitumour polysaccharide lentinan: An overview. In: Aoki T., editor. Manipulation of host defense mechanism. 1969. pp. 687–694. 222. [Google Scholar]

- Choi J.W., Ra K.S., Kim S.Y., Yoon T.J., Yu K.W., Shin K.S., Lee S.P., Suh H.J. Ehancement of anti-complementary and radical scavenging activities in the submerged culture of Cordyceps sinensis by addition of citrus peel. Bioresource Technology. 2010;101:6028–6034. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.02.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui S.W. Structural analysis of polysaccharides. In: Cui Steve W., editor. Food carbohydrates: Chemistry, physical properties and applications (1 edition) CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q., Jiang S., Zhang L., Wu C. Laser light-scattering studies of pachyman. Carbohydrate Research. 1998;308:339–343. [Google Scholar]

- Ding C., Tian P.X., Xue W., Ding X., Yan H., Pan X., Feng X., Xiang H., Hou J., Tian X. Efficacy of Cordyceps sinensis in long term treatment of renal transplant patients. Frontiers in Bioscience (Elite Edition) 2011;3:301–307. doi: 10.2741/e245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C.H., Yao Y.J. Nutritional requirements of mycelial growth of Cordyceps sinensis in submerged culture. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2005;99:483–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C.H., Yao Y.J. In vitro evaluation of antioxidant activities of aqueous extracts from natural and cultured mycelia of Cordyceps sinensis. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2008;41:669–677. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong M., Zhu Q., Wang T., Wang X.L., Ma J.X., Zhang W.J. Molecular structure and immunoactivity of the polysaccharide from Cordyceps sinensis (Berk) Sacc. Chinese Biochemical Journal. 1990;6:486–492. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guan J., Zhao J., Feng K., Hu D.J., Li S.P. Comparison and characterization of polysaccharides from natural and cultured Cordyceps using saccharide mapping. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2011;399:3465–3474. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4396-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutteridge J.M.C., Halliwell B. Oxford University Press; Oxford, New York, NY: 1994. Antioxidants in nutrition, health, and disease. [Google Scholar]

- Hilliou L., Freitas F., Oliveira R., Reis M.A.M., Lespineux D., Grandfils C., Alves V.D. Solution properties of an exopolysaccharide from a Pseudomonas strain obtained using glycerol as sole carbon source. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2009;78:526–532. [Google Scholar]

- Holliday J., Cleaver M. Medicinal value of the caterpillar fungi species of the genus Cordyceps (Fr.) Link (Ascomycetes). A review. International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms. 2008;10:219–234. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C.Y., Tsai M.J., Hsu T.H., Chang D.M., Lo C.T. Medium optimization for polysaccharide production of Cordyceps sinensis. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 2005;120:145–157. doi: 10.1385/abab:120:2:145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu T.H., Shiao L.H., Hsieh C., Chang D.M. A comparison of the chemical composition and bioactive ingredients of the Chinese medicinal mushroom DongChongXiaCao, its counterfeit and mimic, and fermented mycelium of Cordyceps sinensis. Food Chemistry. 2002;78:463–469. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q.L., Siu K.C., Wang W.Q., Cheung Y.C., Wu J.Y. Fractionation, characterization and antioxidant activity of exopolysaccharides from fermentation broth of a Cordyceps sinensis fungus. Process Biochemistry. 2013;48:380–386. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Song D., Yang A., Yin H., Zhang W. Differentiation and maturation of human dendritic cells modulated by an exopolysaccharide from an anamorph of Cordyceps sinensis. Biomedicine & Preventive Nutrition. 2011;1:126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang H.J., Kim S.W., Lim J.M., Joo J.H., Kim H.O., Kim H.M., Yun J.W. Hypoglycemic effect of crude exopolysaccharides produced by a medicinal mushroom Phellinus baumii in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Life Sciences. 2005;76:3069–3080. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang H.S., Yun J.W. Hypoglycemic effect of polysaccharides produced by submerged mycelial culture of Laetiporus sulphureus on streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering. 2010;15:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey G. The ‘Viagra’ transforming local economies in India. BBC News. Retrieved. 2012;09(07):2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ji D.B., Ye J., Li C.L., Wang Y.H., Zhao J., Cai S.Q. Antiaging effect of Cordyceps sinensis extract. Phytotherapy Research. 2009;23:116–122. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwagi Y., Norisuye T., Fujita H. Triple helix of Schizophyllum commune polysaccharide in dilute solution, 4. Light scattering and viscosity in dilute aqueous sodium hydroxide. Macromolecules. 1981;14:1220–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Kiho T., Hui J., Yamane A., Ukai S. Polysaccharide in fungi. XXXII. Hypoglycemic activity and chemical properties of a polysaccharide from the cultural mycelium of Cordyceps sinensis. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1993;16:1291–1293. doi: 10.1248/bpb.16.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiho T., Ookubo K., Usui S., Ukai S., Hirano K. Structural features and hypoglycemic activity of a polysaccharide (CS-F10) from the cultured mycelium of Cordyceps sinensis. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1999;22:966–970. doi: 10.1248/bpb.22.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiho T., Tabata H., Ukai S., Hara C. Polysaccharide in fungi. 18. A minor, protein-containing galactomannan from a sodium-carbonate extract of Cordyceps sinensis. Carbohydrate Research. 1986;156:189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Kiho T., Yamane A., Hui J., Usui S., Ukai S. Polysaccharides in fungi, XXXVI. Hypoglycemic activity of a polysaccharide (CS-F30) from the cultural mycelium of Cordyceps sinensis and its effect on glucose metabolism in mouse liver. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1996;19:294–296. doi: 10.1248/bpb.19.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.D. Isolation, structure and cholesterol esterase inhibitory activity of a polysaccharide, PS-A, from C. sinensis. Journal of the Korean Society from Applied Biological Chemistry. 2010;53:784–789. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.O., Yun J.W. A comparative study on the production of exopolysaccharides between two entomopathogenic fungi Cordyceps militaris and Cordyceps sinensis in submerged mycelial cultures. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2005;99:728–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh J.H., Yu K.W., Suh H.J., Choi Y.M., Ahn T.S. Activation of macrophages and the intestinal immune system by an orally administered decoction from cultured mycelia of Cordyceps sinensis. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 2002;66:407–411. doi: 10.1271/bbb.66.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M.C., Chang C.Y., Cheng T.L., Wu M.J. Immunomodulatory effect of exo-polysacchrides from submerged cultured Cordyceps sinensis: Enhancement of cytokine synthesis, CD11b expression, and phagocytosis. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2007;75:769–775. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0880-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang J., Qi X., Hou Y., Zhao S., Jiang G. Production of exopolysaccharides by Cordyceps sinensis in liquid culture. Journal of Dalian Polytechnic University. 2009;28:107–110. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Leung P.H., Wu J.Y. Effects of ammonium feeding on production of bioactive metabolites (cordycepin and exopolysaccharides) in mycelial culture of a Cordyceps sinensis fungus. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2007;103:1942–1949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung P.H., Zhang Q.X., Wu J.Y. Mycelium cultivation, chemical composition and antitumour activity of a Tolypocladium sp. fungus isolated from wild Cordyceps sinensis. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2006;101:275–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung P.H., Zhao S.N., Ho K.P., Wu J.Y. Chemical properties and antioxidant activity of exopolysaccharides from mycelial culture of Cordyceps sinensis fungus Cs-HK1. Food Chemistry. 2009;114:1251–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Li S.P., Tsim K.W.K. The biological and pharmacological properties of Cordyceps sinensis, a traditional Chinese medicine that has broad clinical applications. In: Packer L., Ong C.N., Halliwell B., editors. Herbal and traditional medicine: Molecular aspects of health. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2004. pp. 657–683. [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Jiang X.L., Guan H.S. Optimization of mycelium biomass and exopolysaccharides production by Hirsutella sp in submerged fermentation and evaluation of exopolysaccharides antibacterial activity. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2010;9:196–203. [Google Scholar]

- Li S.P., Li P., Dong T.T.X., Tsim K.W.K. Anti-oxidation activity of different types of natural Cordyceps sinensis and cultured Cordyceps mycelia. Phytomedicine. 2001;8:207–212. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.P., Su Z.R., Dong T.T.X., Tsim K.W.K. The fruiting body and its caterpillar host of Cordyceps sinensis show close resemblance in main constituents and anti-oxidation activity. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:319–324. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Wang X.L., Jiao L., Jiang Y., Li H., Jiang S.P., Lhosumtseiring N., Fu S.Z., Dong C.H., Zhan Y., Yao Y.J. A survey of the geographic distribution of Ophiocordyceps sinensis. The Journal of Microbiology. 2011;49:913–919. doi: 10.1007/s12275-011-1193-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.P., Zhang G.H., Zeng Q., Huang Z.G., Wang Y.T., Dong T.T.X., Tsim K.W.K. Hypoglycemic activity of polysaccharide, with antioxidation, isolated from cultured Cordyceps mycelia. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:428–433. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.P., Zhao K.J., Ji Z.N., Song Z.H., Dong T.T.X., Lo C.K., Cheung J.K.H., Zhu S.Q., Tsim K.W.K. A polysaccharide isolated from Cordyceps sinensis, a traditional Chinese medicine, protects PC12 cells against hydrogen peroxide-induced injury. Life Sciences. 2003;73:2503–2513. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00652-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Li P., Zhao D., Tang H., Guo J. Protective effect of extract of Cordyceps sinensis in middle cerebral artery occlusion-induced focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Behavioral and Brain Functions. 2010;6:61–68. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-6-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Liu N., Han B., Tian X., Su J., Zhao D. Effect of crude polysaccharides from mycelium of Cordyceps sinensis on expression of p53 gene and induction of apoptosis in SP2/0 cells. Acta Veterinaria et Zootechnica Sinica. 2009;40:117–121. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.S., Wu J.Y. Effects of Tween 80 and pH on mycelial pellets and exopolysaccharide production in liquid culture of a medicinal fungus. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2012;39:623–628. doi: 10.1007/s10295-011-1066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo H.C., Hsieh C., Lin F.Y., Hsu T.H. A Systematic Review of the Mysterious Caterpillar Fungus Ophiocordyceps sinensis in DongChongXiaCao and Related Bioactive Ingredients. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine. 2013;3:16–32. doi: 10.4103/2225-4110.106538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchbank T., Ojobo E., Playford G., Playford R. Reparative properties of the traditional Chinese medicine Cordyceps sinensis (Chinese caterpillar mushroom) using HT29 cell culture and rat gastric damage models of injury. British Journal of Nutrition. 2011;105:1303–1310. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510005118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R., Janeway C. Innate immune recognition: mechanisms and pathways. Immunological Reviews. 2000;173:89–97. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.917309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki T., Oikawa N., Yamada H. Studies on fungal polysaccharides. 20. Galactomannan of Cordyceps sinensis. Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1977;25:3324–3328. [Google Scholar]

- Moradali M., Mostafavi H., Ghods S., Hedjaroude G. Immunomodulating and anticancer agents in the realm of macromycetes fungi (macrofungi) International Immunopharmacology. 2007;7:701–724. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negre-Salvayre A., Coatrieux C., Ingueneau C., Salvayre R. Advanced lipid peroxidation end products in oxidative damage to proteins. Potential role in diseases and therapeutic prospects for the inhibitors. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2008;153:6–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie S.P., Cui S.W., Phillips A.O., Xie M.Y., Phillips G.O., Al-Assaf S., Zhang X.L. Elucidation of the structure of a bioactive hydrophobic polysaccharide from Cordyceps sinensis by methylation analysis and NMR spectroscopy. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2011;84:894–899. [Google Scholar]

- Nie S.P., Cui S.W., Xie M., Phillips A.O., Phillips G.O. Bioactive polysaccharides from Cordyceps sinensis: isolation, structure features and bioactivities. Bioactive Carbohydrates and Dietary Fiber. 2013;1:38–52. [Google Scholar]

- Nie S.P., Xie M.Y. A review on the isolation and structure of tea polysaccharides and their bioactivities. Food Hydrocolloids. 2011;25:144–149. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotopoulos C., Sempéré R., Lafont R., Kerhervé P. Sub-ambient temperature effects on the separation of monosaccharide by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulse amperometric detection: application to marine chemistry. Journal of Chromatography A. 2001;920:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)00697-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson R.R.M. Cordyceps – a traditional Chinese medicine and another fungal therapeutic biofactory? Phytochemistry. 2008;69:1469–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez S., Kouwijzer M., Mazeau K., Engelsen S.B. Modeling polysaccharides: present status and challenges. Journal of Molecular Graphics. 1996;14:307–321. doi: 10.1016/s0263-7855(97)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pol-Fachin L., Fernandes C.L., Verli H. GROMOS96 43a1 performance on the characterization of glycoprotein conformational ensembles through molecular dynamics simulations. Carbohydrate Research. 2009;344:491–500. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan W., Wang J., Du S., Liu G. Studies on the production of exopolysaccharides by liquid culture of Cordyceps sinensis. Fajiao Keji Tongxun. 2007;36:2–4. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Norisuye T., Fujita H. Double-stranded helix of xanthan: dimensional and hydrodynamic properties in 0.1 M aqueous sodium chloride. Macromolecules. 1984;17:2696–2700. [Google Scholar]

- Schlesier K., Harwat M., Böhm V., Bitsch R. Assessment of antioxidant activity by using different in vitro methods. Free Radical Research. 2002;36:177–187. doi: 10.1080/10715760290006411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senti F.r., Hellman N.N., Ludwig N.H., Babcock G.E., Tobin R., Glass C.A., Lamberts B.L. Viscosity, sedimentation, and light-scattering properties of fraction of an acid-hydrolyzed dextran. Journal of Polymer Science. 1955;17:527–546. [Google Scholar]

- Shashidhar M.G., Giridhar P., Sankar K.U., Manohar B. Bioactive principles from Cordyceps sinensis: A potent food supplement – A review. Journal of Functional Foods. 2013;5:1013–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Shao X., Ni Y., Xu H., Tong X. Cordyceps sinensis polysaccharide enhances apoptosis of HL-60 cells induced by triptolide. Journal of Zhejiang University (Medical Sciences) 2009;38:158–162. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2009.02.007. (in Chinese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W., Song D., Wu J., Zhang W. Protective effects of a polysaccharide isolated from a cultured Cordyceps mycelia on hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage in PC12 cells. Phytotherapy Research. 2011;25:675–680. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng L., Chen J., Li J., Zhang W. An exopolysaccharide from cultivated Cordyceps sinensis and its effects on cytokine expression of immunocytes. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 2011;163:669–678. doi: 10.1007/s12010-010-9072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D., He Z., Wang C., Yuan F., Dong P., Zhang W. Regulation of the exopolysaccharide from an anamorph of Cordyceps sinensis on dendritic cell sarcoma (DCS) cell line. European Journal of Nutrition. 2013;52:687–694. doi: 10.1007/s00394-012-0373-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D., Lin J., Yuan F., Zhang W. Ex vivo stimulation of murine dendritic cells by an exopolysaccharide from one of the anamorph of Cordyceps sinensis. Cell Biochemistry and Function. 2011;29:555–561. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L.Q., Ming Y.S., Peng M.X., Xia J.L. The protective effects of Cordyceps sinensis extract on extracellular matrix accumulation of glomerular sclerosis in rats. African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2010;4:471–478. [Google Scholar]

- Strlegel A.M., Plattner R.D., Willett J.L. Dilute solution behavior of dendrimers and polysaccharides: SEC, ESI-MS, and computer modeling. Analytical Chemistry. 1999;71:978–986. doi: 10.1021/ac980871f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velickovic D.T., Milenovic D.M., Ristic M.S., Veljkovic V.B. Kinetics of ultrasonic extraction of extractive substances from garden (Salvia officinalis L.) and glutinous (Salvia glutinosa L.) sage. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 2006;13:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.M., Cheung Y.C., Leung P.H., Wu J.Y. Ultrasonic treatment for improved solution properties of a high-molecular weight exopolysaccharide produced by a medicinal fungus. Bioresource Technology. 2010;101:5517–5522. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.01.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.L., Liu G.Q., Zhu C.Y., Kuang S.M. Enhanced production of mycelial biomass and extracellular polysaccharides in caterpillar-shaped medicinal mushroom Cordyceps sinensis CS001 by the addition of palmitic acid. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2011;5:2873–2878. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.M., Peng X., Lee K.L.D., Tang J.C., Cheung P.C.K., Wu J.Y. Structural characterisation and immunomodulatory property of an acidic polysaccharide from mycelial culture of Cordyceps sinensis fungus Cs-HK1. Food Chemistry. 2011;125:637–643. [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.Y., Shiao M.S. Pharmacological functions of Chinese medicinal fungus Cordyceps sinensis and related species. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis. 2000;8:248–257. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wang M., Ling Y., Fan W.Q., Wang Y.F., Yin H.P. Structural determination and antioxidant activity of a polysaccharide from the fruiting bodies of cultured Cordyceps sinensis. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2009;37:977–989. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X09007387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Wang G., Zhang J., Zhang G., Jia L., Liu X., Deng P., Fan K. Extraction optimization and antioxidant activity of intracellular selenium polysaccharide by Cordyceps sinensis SU-02. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2011;86:1745–1750. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Yin H., Chen T., Wang M. Preliminary structural identification and protection on renal cell injury of acidic polysaccharide from Cordyceps sinensis. Journal of China Pharmaceutical University. 2009;40:559–564. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Yin H., Lv X., Wang Y., Gao H., Wang M. Protection of chronic renal failure by a polysaccharide from Cordyceps sinensis. Fitoterapia. 2010;81:397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasser S.P. Medicinal mushrooms as a source of antitumour and immunomodulating polysaccharides. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2002;10:13–32. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasser S.P., Weis A.L. Medicinal properties of substances occurring in higher basidiomycetes mushroom: current perspective. International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms. 1999;1:31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler D. Caterpillar fungus (Ophiocordyceps sinensis) production and sustainability on the Tibetan Plateau and in the Himanayas. Asian Medicines. 2009;5:291–316. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler D. Cordyceps sinensis – a previous parasitic fungus infecting Tibet. Field Mycology. 2010;11:60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wong W.C., Wu J.Y., Benzie I.F.F. Photoprotective potential of Cordyceps polysaccharides against ultraviolet B radiation-induced DNA damage to human skin cells. British Journal of Dermatology. 2011;164:980–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C., Chen Y., Hao Y. Production of mycelia and polysaccharides by liquid fermentation of Cordyceps sinensis. Food Science. 2009;30:171–174. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.L., Hu N., Pan Y.J., Zhou L.J., Zhou X.X. Isolation and characterization of a mannoglucan from edible Cordyceps sinensis mycelium. Carbohydrate Research. 2007;342:870–875. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.L., Ishurd O., Sun C.R., Pan Y.J. Structure analysis and antitumour activity of (1 → 3)-beta-d-glucans (Cordyglucans) from the mycelia of Cordyceps sinensis. Planta Medica. 2005;71:381–384. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-864111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.L., Sun C.R., Pan Y.J. Structural analysis of a neutral (1 → 3), (1 → 4)-β-d-glucan from the mycelia of Cordyceps sinensis. Journal of Natural Products. 2005;68:812–814. doi: 10.1021/np0496035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.L., Sun C.R., Pan Y.J. Studies on isolation and structural features of a polysaccharide from the mycelium of a Chinese edible fungus (Cordyceps sinensis) Carbohydrate Polymers. 2006;63:251–256. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.L., Sun H.X., Qin F., Pan Y.J., Sun C.R. Effect of various extracts and a polysaccharide from the edible mycelia of Cordyceps sinensis on cellular and humoral immune response against ovalbumin in mice. Phytotherapy Research. 2006;20:646–652. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J.H. Current status and ponderation on preparations and chemical structures of polysaccharide in fungi of Cordyceps (Fr.) Link. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs. 2008;39:454–460. [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., Shan B., Zhang W. Microwave-assisted extraction of polysaccharides from fermented Cordyceps sinensis mycelium optimized by response surface analysis. Chinese Journal of Bioprocess Engineering. 2009;7:34–38. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yamac M., Kanbak G., Zeytinoglu M., Bayramoglu G., Senturk H., Uyanoglu M. Hypoglycemic effect of Lentinus strigosus (Schwein.) fr. crude exopolysaccharide in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2008;11:513–517. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2007.0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H., Kawaguchi N., Ohmori T., Takeshita Y., Taneya S., Miyazaki T. Strucrual and antitumour activity of an alkali-soluble polysaccharide from Cordyceps ophioglossoides. Carbohydrate Research. 1984;125:107–115. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(84)85146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J.K., Li L., Wang Z.M., Leung P.H., Wang W.Q., Wu J.Y. Acidic degradation and enhanced antioxidant activities of exopolysaccharides from Cordyceps sinensis mycelial culture. Food Chemistry. 2009;117:641–646. [Google Scholar]

- Yan J.K., Li L., Wang Z.M., Wu J.Y. Structural elucidation of an exopolysaccharide form mycelial fermentation of a Tolypocladium sp. fungus isolated from wild Cordyceps sinensis. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2010;79:125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Yan J.K., Wang W.Q., Li L., Wu J.Y. Physiochemical properties and antitumour activities of two α-glucans isolated from hot water and alkaline extracts of Cordyceps (Cs-HK1) fungal mycelia. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2011;85:753–758. [Google Scholar]

- Yan J.K., Wang W.Q., Ma H.L., Wu J.Y. Sulfation and enhanced antioxidant capacity of an exopolysaccharide produced by the medicinal fungus Cordyceps sinensis. Molecules. 2013;18:167–177. doi: 10.3390/molecules18010167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan F., Zhang Y., Wang B. Effects of polysaccharides from Cordyceps sinensis mycelium on physical fatigue in mice. Bangladesh Journal of Pharmacology. 2012;7:217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.Y., Chen A., Kuo Y.C., Lin C.Y. Efficacy of a pure compound H1-A extracted from Cordyceps sinensis on autoimmune disease of MRL LPR/LPR mice. The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 1999;134:492–500. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(99)90171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.Y., Huang W.J., Hsieh H.G., Lin C.Y. H1-A extracted from Cordyceps sinensis suppresses the proliferation of human mesangial cells and promotes apoptosis, probably by inhibiting the tyrosine phosphorylation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL. The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 2003;141:74–83. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2003.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Zhang L.M. Chemical structural and chain conformational characterization of some bioactive polysaccharides isolated from natural sources. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2009;76:349–361. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.Y., Zhang W.Y., Shi P.H., Chen J.P., Han X.D., Wang Y. Effects of exopolysaccharide fraction (EPSF) from a cultivated Cordyceps sinensis fungus on c-Myc, c-Fos, and VEGF expression in B16 melanoma-bearing mice. Pathology, Research and Practice. 2005;201:745–750. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y.J. Conservation and rational use of the natural resources of Cordyceps sinensis. Science News. 2004;15:28–29. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yao X., Meran S., Fang Y., Martin J., Midgley A., Pan M.M., Liu B.C., Cui S.W., Phillips G.O., Phllips A.O. Cordyceps sinensis: in vitro anti-fibrotic bioactivity of natural and cultured preparations. Food Hydrocolloids. 2014;35:444–452. [Google Scholar]

- Yin H., Qiao C., Qin S., Tang W., Jia S. Optimization of fermentation medium for Cordyceps sinensis. Food Research & Development. 2013;34:5–8. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yin D.H., Tang X.M. Progresses of cultivation research of Cordyceps sinensis. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 1995;20:707–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon T.J., Yu K.W., Shin K.S., Suh H.J. Innate immune stimulation of exo-polymers prepared from Cordyceps sinensis by submerged culture. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2008;80:1087–1093. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1607-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue K., Ye M., Zhou Z., Sun W., Lin X. The genus Cordyceps: a chemical and pharmacological review. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2013;65:474–493. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2012.01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.L., Cheung L.B., Al-Assaf S., Phillips G.O., Phillips A.O. Cordyceps sinensis decreases TGF-β1 dependent epithelial to mesenchymal transdifferentiation and attenuates renal fibrosis. Food Hydrocolloids. 2012;28:200–212. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Cui S., Cheung P., Wang Q. Antitumour polysaccharides from mushrooms: a review on their isolation process, structural characteristics and antitumour activity. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2007;18:4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G.Q., Huang Y.D., Bian Y., Wong J.H., Ng T.B., Wang H.X. Hypoglycemic activity of the fungi Cordyceps militaris, Cordyceps sinensis, Tricholoma mongolicum, and Omphalia lapidescens in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2006;72:1152–1156. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0411-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Li J., Qiu S., Chen J., Zheng Y. Effects of the exopolysaccharide fraction (EPSF) from a cultivated C. sinensis on immunocytes of H22 tumour bearing mice. Fitoterapia. 2008;79:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Li E., Wang C., Li Y., Liu X. Ophiocordyceps sinensis, the flagship fungus of China: terminology, life strategy and ecology. Mycology. 2012;3:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Wang X., Zhang Y., Ye G. Effect of Cordyceps sinensis on renal function of patients with chronic allograft nephropathy. Urologia Internationalis. 2011;86:298–301. doi: 10.1159/000323655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Yang L. Solution properties of pachyman from Poria cocos mycelia in dimenthyl sulfoxide. Biopolymers. 1995;36:695–700. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.Y., Yang J.Y., Chen J.P., Hou Y.Y., Han X.D. Immunomodulatory and antitumour effects of an exopolysaccharide fraction from cultivated Cordyceps sinensis (Chinese caterpillar fungus) on tumour-bearing mice. Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry. 2005;42:9–15. doi: 10.1042/BA20040183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Xie J., Wang L.Y., Li S.P. Advanced development in chemical analysis of Cordyceps. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.04.025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S., Pan H.J., Fan L.F., Lv G., Wu Y., Parmeswaran B., Pandey A., Soccol C.R. Advances in research of polysaccharides in Cordyceps species. Food Technology and Biotechnology. 2009;47:304–312. [Google Scholar]