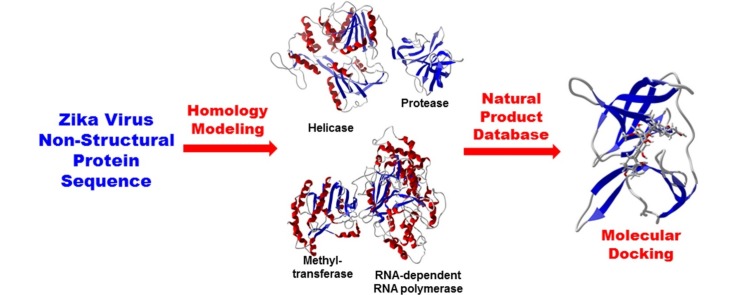

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Zika virus, Neglected tropical disease, Homology model, Molecular docking

Highlights

-

•

Zika viral infection is an emerging infectious disease in the Western hemisphere.

-

•

There are no vaccines or antiviral agents available for Zika virus infections.

-

•

There is only one structure available of Zika virus protein targets.

-

•

Zika virus targets were generated using homology modeling techniques.

-

•

An in-silico search for phytochemical anti-Zika viral agents was carried out.

Abstract

Zika virus (ZIKV) is an arbovirus that has infected hundreds of thousands of people and is a rapidly expanding epidemic across Central and South America. ZIKV infection has caused serious, albeit rare, complications including Guillain–Barré syndrome and congenital microcephaly. There are currently no vaccines or antiviral agents to treat or prevent ZIKV infection, but there are several ZIKV non-structural proteins that may serve as promising antiviral drug targets. In this work, we have carried out an in-silico search for potential anti-Zika viral agents from natural sources. We have generated ZIKV protease, methyltransferase, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase using homology modeling techniques and we have carried out molecular docking analyses of our in-house virtual library of phytochemicals with these protein targets as well as with ZIKV helicase. Overall, 2263 plant-derived secondary metabolites have been docked. Of these, 43 compounds that have drug-like properties have exhibited remarkable docking profiles to one or more of the ZIKV protein targets, and several of these are found in relatively common herbal medicines, suggesting promise for natural and inexpensive antiviral therapy for this emerging tropical disease.

1. Introduction

Zika virus (ZIKV) is an emerging arbovirus that belongs to the genus Flavivirus in the family Flaviviridae. Other members of the genus include the West Nile virus, dengue virus, yellow fever virus, and tick-borne encephalitis virus [1]. Zika virus was initially isolated from a rhesus monkey in the Zika forest of Uganda [2]. There had been sporadic human infections in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia [3]. However, in 2007 there was an outbreak in Yap Island (Micronesia) and subsequent epidemics in French Polynesia, New Caledonia, the Cook Islands, and Easter Island between 2013 and 2014 [4]. In 2015 the number of human infections with ZIKV showed a dramatic increase in the tropical Americas, particularly Brazil [5], [6]. By the end of 2015, there have been an estimated 0.5–1.3 million cases of ZIKV infection [7].

The virus is primarily transmitted by Aedes spp. mosquitoes, including Ae. aegypti, Ae. africanus, Ae. apicoargenteus, Ae. furcifer, Ae. hensilli, Ae. luteocephalus, and Ae. vitattus [3]. However, there is now evidence that the disease can be sexually transmitted; replicative Zika viruses have been found in the semen of an infected man [8]. In addition, there is evidence that the virus can be transmitted perinatally and transplacentally; Zika viral RNA has been detected in amniotic fluid samples from fetuses of infected mothers [9]. Zika virus infections are typically characterized with symptoms of maculopapular rash, fever, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, and conjunctivitis. In addition, however, ZIKV infection has been associated with additional complications such as Guillain–Barré syndrome [10], congenital microcephaly [11], and macular atrophy [12].

There are currently no vaccines or antiviral agents available to treat or prevent Zika virus infection [13]. However, several Flavivirus non-structural proteins have been implicated as potential targets for antiviral drug discovery.

1.1. Zika virus protease

ZIKV protease (NS2B-NS3pro) is a trypsin-like serine protease that cleaves the ZIKV polyprotein into individual proteins necessary for viral replication. Flaviviral proteases from dengue virus [14] and West Nile virus [15] have been identified as a potential targets for development of antiviral agents [16].

1.2. Zika virus helicase

Flaviviral NS3 helicases possess RNA helicase, nucleoside and RNA triphosphatase activities and are involved both in viral RNA replication and virus particle formation. They are essential for viral replication and have been identified as potential drug targets [17].

1.3. Zika virus methyltransferase

The flavivirus NS5 methyltransferase (MTase) enzyme is responsible for methylating the viral RNA cap structure [18]. Viruses deficient in cap methylation result in attenuated or non-replicative viruses, and therefore, MTase is an attractive target for discovery of antiviral agents [19], [20].

1.4. Zika virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

RNA-dependent RNA polymerases are employed by flaviviruses and are responsible for initiating and catalyzing replication of viral RNA synthesis in the cytoplasm of infected cells. There are no similar enzymes found in the host since host cells do not require RNA replication. This enzyme, then, is considered to be a prime target for antiviral development [21], [22].

In this work, we have carried out an in-silico search for potential anti-Zika viral agents from natural sources. We have generated ZIKV protease, methyltransferase, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase using homology modeling techniques and we have carried out molecular docking analyses of our in-house virtual library of phytochemicals with these protein targets and with the X-ray crystal structure of ZIKV helicase.

2. Methodology

2.1. Homology modeling

Currently there is only one protein structure available (helicase, PDB 5JMT [23]) for Zika virus non-structural proteins. Homology models for each of the other Zika proteins listed in Table 1 were constructed from crystal structure templates found in the Protein Data Bank using FASTA sequences downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s (NCBI) GenBank. Sequences with high sequence similarity in the PDB were identified with NCBI’s BLAST utility using the BLOSUM80 scoring matrix. Sequences with high similarity to the reference sequence, as well as having good coverage for the active sites in the protein, were chosen for single reference homology modeling.

Table 1.

Homology models for Zika virus non-structural proteins.

| Protein | GenBank Accession Number | Reference Structure |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB Entry | Sequence Identity | E-value | ||

| NS3 Protease | AHL16750.1 | 2WV9a | 72% | 5 × 10−135 |

| NS5 MTase | A0A0B4ZYV2 | 4K6M | 72% | 2 × 10−157 |

| NS5 RdRp | A0A0B4ZYV2 | 4K6M | 72% | 2 × 10−157 |

| NS5 RdRp | A0A0B4ZYV2 | 2HFZ | 73% | 3 × 10−171 |

Homology model was constructed with superposed ligand of PDB 2FP7.

The protein sequences were first aligned to their respective template sequences using the BLOSUM62 substitution matrix and a protein backbone constructed and superposed to the reference structure using the protein alignment tool in MOE 2014.0901. The homology modeling interface in MOE was used to generate a set of putative protein structures by aligning atomic coordinates of the amino acid sequence to those of the template sequence backbone and minimizing permutations of side chain orientations using the AMBER10:EHT force field [24], [25], [26] with reaction field solvation. The candidate structure with the lowest RMSD deviation from the template backbone was selected and optimized using a constrained minimization.

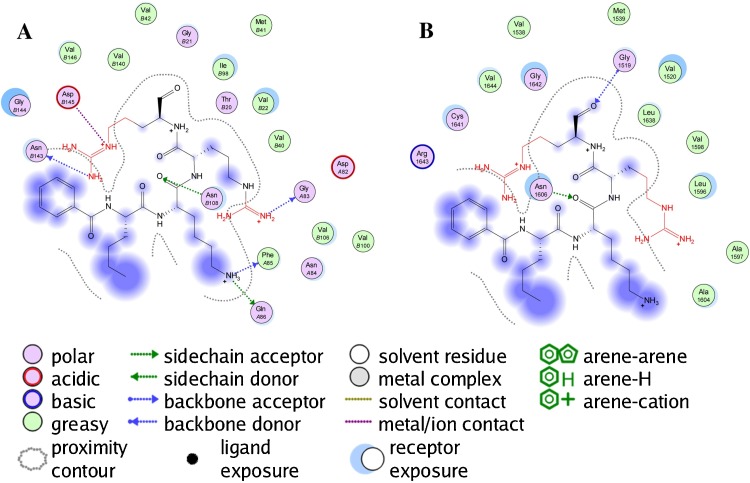

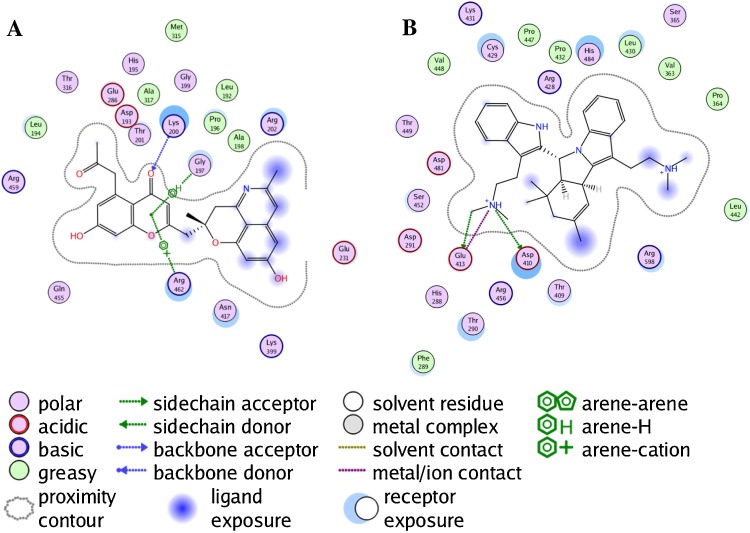

The homology models for the NS3 protease was generated for the stretch of the whole Zika protein (accession number Q32ZE1) that correspond to the incomplete 257 amino acid NSP3 sequence, AHL16750.1, found in the NCBI GenBank. The closest matching template in the PDB was the combined NSP3 Protease-Helicase from Dengue Virus (2WHX) [27]. The protease binding site in this template is poorly defined in the crystal structure with the highest similarity (2WV9) [28], so a second template, from the homologous protease in West Nile Virus (2FP7; exp. value 4 × 10−7) [29] with a bound ligand (Bz-Nle-Lys-Arg-Arg-H; (N-benzoyl-l-norleucyl-6-ammonio-l-norleucyl-N-5-[amino(imino)methyl]-N-[(2S)-5-carbamimidamido-1-hydroxypentan-2-yl]-l-ornithinamide)) was used to generate a homology model specifically for the protease. Since the sequence similarity with the NS3 protease is much lower for this template, a constrained minimization of the peptide-receptor complex was carried out using the AMBER10:EHT force field and the bound peptide removed prior to docking. The RMSD between 2FP7 and the homology model is 0.753 Å for all common atoms. The binding interactions for both are shown in Fig. 1 . The GenBank protein sequence A0A0B4ZYV2 was used for the NS5 methyltransferase and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase homology models using the relevant portion of the complete NS5 protein from Japanese Encephalitis Virus (4K6M) [30]. A second homology model for NS5 RdRp was generated using the template structure 2HFZ from West Nile Virus [31]. Protein sequence alignments and Ramachandran plots of the template proteins and the homology modeled ZIKV proteins are available as Supplementary material.

Fig. 1.

Ligand-receptor interaction map of Bz-Nle-Lys-Arg-Arg-H with the West Nile virus NS2B-NS3 protease (PDB 2FP7) (panel A) and homology-modeled Zika virus NS2B-NS3 protease (panel B).

2.2. Molecular docking

Protein-ligand docking studies were carried out based on homology-modeled structures of Zika virus (ZIKV) NSPB/NS3 protease, based on the crystal structure of Murray Valley encephalitis virus protease, PDB 2WV9 [28]; ZIKV NS5 methyltransferase (MTase), based on the crystal structure of Japanese encephalitis virus methyltransferase, PDB 4K6M [30]; and ZIKV NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), based on crystal structures of West Nile virus RdRp, PDB 2HFZ [31] and Japanese encephalitis virus RdRp, PDB 4K6M [30]. Molecular docking calculations for all compounds with each of the proteins were undertaken using Molegro Virtual Docker (version 6.0, Molegro ApS, Aarhus, Denmark) [32], with a sphere large enough to accommodate the cavity centered on the binding sites of each protein structure in order to allow each ligand to search. Standard protonation states of the proteins based on neutral pH were used in the docking studies. Each protein was used as a rigid model structure; no relaxation of the protein was performed. Assignments of charges on each protein were based on standard templates as part of the Molegro Virtual Docker program; no other charges were necessary to be set. Overall, 2263 plant-derived secondary metabolites have been docked. This molecule set was comprised of 384 alkaloids (158 indole alkaloids, 143 isoquinoline alkaloids, 5 quinoline alkaloids, 18 piperidine alkaloids, 14 steroidal alkaloids, and 46 miscellaneous alkaloids), 670 terpenoids (35 monoterpenoids, 153 sesquiterpenoids, 212 diterpenoids, 83 steroids, 51 limonoids, 42 withanolides, and 97 triterpenoids), 1043 polyphenolic compounds (22 aurones, 72 chalcones, 9 chromones, 111 coumarins, 297 flavonoids, 113 isoflavonoids, 69 lignans, 69 stilbenoids, 29 xanthones, and 172 miscellaneous phenolics), and 166 miscellaneous phytochemicals. This in-house virtual library represents a practical selection of phytochemical classes and structural types. Each ligand structure was built using Spartan ’14 for Windows (version 1.1.8, Wavefunction Inc., Irvine, California). For each ligand, a conformational search and geometry optimization was carried out using the MMFF force field [33]. Flexible ligand models were used in the docking and subsequent optimization scheme. Variable orientations of each of the ligands were searched and ranked based on their re-rank score. For each docking calculation the maximum number of iterations for the docking algorithm was set to 1500, with a maximum population size of 50, and 30 runs per ligand. The RMSD threshold for multiple poses was set to 1.00 Å. The generated poses from each ligand were sorted by the calculated re-rank score. In analyzing the docking scores, we have attempted to account for the recognized bias toward high molecular weight compounds [34], [35], [36], [37]. We have used two different schemes to re-evaluate the Molegro docking scores (Edock): (1) E′ = 6.96 × Edock/MW⅓, which accounts for biasing by dividing by a molecular weight function (MW), where 6.96 is a scaling constant to bring the average E′ values comparable to Edock; and (2) E′′ = Edock − 18.3 − Edock × NH/125, which reduces the bias by subtracting a contribution from the number of non-hydrogen atoms (NH), where 18.3 is a factor to bring average E″ values comparable to Edock. Histograms of docking scores for each protein target are available as Supplementary material.

3. Results and discussion

A total of 2263 plant-derived natural products have been docked with Zika virus NS2B-NS3 protease, NS3 helicase, NS5 methyltransferase, and NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Selected phytochemical ligands with notable docking profiles and that adhere to Lipinski’s rule-of-five for drug likeness [38] are listed in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Molegro docking scores (kJ/mol) and normalized scores for phytochemical ligands with Zika virus non-structural proteins.

| Phytochemical Ligand (MW, NH, HBD, HBA, ClogP)a |

ZIKV protein | Edockb | E′c | E′′d | Phytochemical and Bioactivity Notes and References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALKALOIDS | |||||

4,4′-Dimethylisoborreverine (508.74, 38, 1, 4, 4.30) |

Protease | −85.3 | −74.3 | −77.6 | Isolated from Flindersia fournieri[39]. Isolated from Flindersia amboinensis; shows antimalarial activity [40]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −144.2 | −125.7 | −118.6 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −87.7 | −76.5 | −79.4 | ||

| MTase | −128.1 | −111.7 | −107.5 | ||

| RdRp | −116.6 | −101.7 | −99.5 | ||

Cassiarin D (445.47, 33, 2, 7, 2.14) |

Protease | −86.4 | −78.7 | −81.9 | Isolated from the flowers of Cassia siamea; shows antiplasmodial activity [41]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −117.2 | −106.8 | −104.5 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −150.7 | −137.3 | −106.4 | ||

| MTase | −109.7 | −100.0 | −92.5 | ||

| RdRp | −104.5 | −95.2 | −88.1 | ||

Flinderole A (480.69, 36, 3, 4, 1.67) |

Protease | −103.7 | −92.1 | −92.1 | Isolated from Flindersia acuminata; shows antimalarial activity [40]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −131.5 | −116.8 | −111.9 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −139.1 | −123.6 | −117.4 | ||

| MTase | −125.5 | −111.5 | −107.7 | ||

| RdRp | −127.8 | −113.5 | −109.3 | ||

Terrestribisamide (440.49, 32, 4, 8, 2.67) |

Protease | −77.6 | −71.0 | −76.1 | From the fruit of Tribulus terrestris[42]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −140.3 | −128.3 | −122.6 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −116.7 | −106.8 | −105.2 | ||

| MTase | −151.3 | −138.4 | −130.8 | ||

| RdRp | −119.2 | −109.0 | −107.0 | ||

| AURONES | |||||

Kanzonol V (376.45, 28, 2, 4, 4.47) |

Protease | −83.0 | −80.0 | −82.7 | Isolated from licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) roots [43]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −110.4 | −106.4 | −103.9 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −133.6 | −128.8 | −122.0 | ||

| MTase | −127.1 | −122.5 | −117.0 | ||

| RdRp | −105.0 | −101.2 | −99.8 | ||

| CHALCONES | |||||

1-[2,4-Dihydroxy-3-(3-methyl-2-butenyl)phenyl]-3-(8-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-2H-1-benzopyran-6-yl)-2-propen-1-one (406.47, 30, 3, 5, 4.81) |

Protease | −83.2 | −78.2 | −81.5 | From licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) root; inhibitor of influenza virus neuraminidase [44]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −123.3 | −115.9 | −112.0 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −141.9 | −133.3 | −126.2 | ||

| MTase | −125.6 | −118.0 | −113.7 | ||

| RdRp | −116.2 | −109.2 | −106.6 | ||

Angusticornin B (424.49, 31, 5, 6, 3.70) |

Protease | −99.1 | −91.8 | −92.8 | Isolated from Dorstenia angusticornis; shows antibacterial activity [45]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −124.5 | −115.3 | −112.0 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −149.6 | −138.6 | −130.8 | ||

| MTase | −120.8 | −111.9 | −109.1 | ||

| RdRp | −114.4 | −106.0 | −104.3 | ||

Balsacone B (420.45, 31, 4, 6, 3.70) |

Protease | −85.4 | −79.3 | −82.5 | Isolated from the buds of Populus balsamifera; shows antibacterial activity [46]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −123.1 | −114.4 | −110.9 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −143.9 | −133.7 | −126.5 | ||

| MTase | −120.7 | −112.2 | −109.1 | ||

| RdRp | −111.8 | −103.9 | −102.4 | ||

Corylifol B (340.37, 25, 4, 5, 3.80) |

Protease | −83.6 | −83.3 | −85.2 | Isolated from Psoralea corylifolia; shows antibacterial activity [47]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −109.9 | −109.5 | −106.2 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −132.1 | −131.7 | −124.0 | ||

| MTase | −109.9 | −109.6 | −106.2 | ||

| RdRp | −110.5 | −110.2 | −106.7 | ||

Crotaorixin (354.40, 26, 3, 5, 4.06) |

Protease | −90.2 | −88.7 | −89.7 | Isolated from the aerial parts of Crotalaria orixensis; shows antiplasmodial activity [48]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −120.4 | −118.5 | −113.7 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −135.9 | −133.6 | −125.9 | ||

| MTase | −120.2 | −118.2 | −113.5 | ||

| RdRp | −100.4 | −98.7 | −97.8 | ||

Kanzonol Y (410.50, 30, 4, 5, 4.48) |

Protease | −95.6 | −89.5 | −90.9 | Isolated from licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) roots [43]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −120.4 | −112.8 | −109.8 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −143.3 | −134.2 | −127.2 | ||

| MTase | −128.8 | −120.6 | −116.2 | ||

| RdRp | −111.9 | −104.8 | −103.3 | ||

Kuraridin (438.51, 32, 4, 6, 5.16) |

Protease | −100.6 | −92.2 | −93.2 | Isolated from Sophora angustifolia[49] and Sophora flavescens; shows antibacterial [50] and tyrosinase inhibitory [51], and anti-reoviral [52] activities. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −127.0 | −116.4 | −112.8 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −141.1 | −129.2 | −123.2 | ||

| MTase | −134.4 | −123.1 | −118.3 | ||

| RdRp | −115.1 | −105.5 | −103.9 | ||

Licoagrochalcone D (354.40, 26, 2, 5, 3.09) |

Protease | −74.5 | −73.3 | −77.3 | Constituent of hairy root cultures of Glycyrrhiza glabra[53]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −111.5 | −109.7 | −106.6 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −125.6 | −123.5 | −117.8 | ||

| MTase | −103.2 | −101.5 | −100.0 | ||

| RdRp | −111.7 | −109.8 | −106.8 | ||

| COUMARINS | |||||

Licocoumarin A (406.47, 30, 3, 5, 5.39) |

Protease | −74.5 | −70.0 | −74.9 | Isolated from Glycyrrhiza glabra roots [54]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −108.9 | −102.4 | −101.1 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −140.1 | −131.6 | −124.8 | ||

| MTase | −124.4 | −116.9 | −112.9 | ||

| RdRp | −108.5 | −101.9 | −100.8 | ||

3-Hydroxy-9-methoxy-2-[2′ (E)-4′-hydroxy-3′-methylbutenyl]-8- isoprenylcoumestan (434.48, 32, 2, 6, 4.41) |

Protease | −87.5 | −80.4 | −83.4 | Isolated from the roots of Picralima nitida; shows antibacterial activity [55]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −121.7 | −111.8 | −108.8 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −131.2 | −120.5 | −115.9 | ||

| MTase | −129.3 | −118.9 | −114.5 | ||

| RdRp | −109.4 | −100.5 | −99.7 | ||

| FLAVONOIDS | |||||

3′-O-Methyldiplacone (438.51, 32, 3, 6, 4.62) |

Protease | −85.5 | −78.3 | −81.9 | Isolated from the fruits of Poulownia tomentosa; shows antibacterial [56] and antiprotozoal [57] activities. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −127.4 | −116.7 | −113.1 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −155.9 | −142.8 | −134.3 | ||

| MTase | −118.8 | −108.9 | −106.7 | ||

| RdRp | −122.2 | −112.0 | −109.2 | ||

Bonannione A (408.49, 30, 3, 5, 4.75) |

Protease | −80.8 | −75.8 | −79.7 | Isolated from the fruits of Paulownia tomentosa; shows cytotoxic activity [58]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −121.3 | −113.8 | −110.5 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −134.6 | −126.2 | −120.6 | ||

| MTase | −119.0 | −111.7 | −108.8 | ||

| RdRp | −115.4 | −108.2 | −106.0 | ||

Cannflavin A (436.50, 32, 3, 6, 4.39) |

Protease | −92.1 | −84.5 | −86.8 | Isolated from Cannabis sativa[59]; shows antiprotozoal activity [57]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −131.7 | −120.8 | −116.3 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −139.8 | −128.1 | −122.2 | ||

| MTase | −126.9 | −116.5 | −112.7 | ||

| RdRp | −120.3 | −110.4 | −107.8 | ||

Exiguaflavanone A (438.51, 32, 3, 6, 4.59) |

Protease | −91.7 | −84.0 | −86.5 | Isolated from Artemisia indica; shows antimalarial activity [60]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −115.0 | −105.3 | −103.8 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −156.1 | −143.0 | −134.4 | ||

| MTase | −130.4 | −119.5 | −115.3 | ||

| RdRp | −103.9 | −95.2 | −95.6 | ||

Exiguaflavanone B (424.49, 31, 4, 6, 4.32) |

Protease | −82.6 | −76.5 | −80.4 | Isolated from Artemisia indica; shows antimalarial activity [60]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −107.9 | −99.9 | −99.5 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −134.5 | −124.5 | −119.4 | ||

| MTase | −125.2 | −116.0 | −112.5 | ||

| RdRp | −102.4 | −94.8 | −95.3 | ||

Flemiflavanone D (424.49, 31, 3, 6, 3.56) |

Protease | −82.9 | −76.8 | −80.6 | Isolated from Flemingia stricta; shows antibacterial activity [61]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −123.4 | −114.2 | −111.1 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −140.5 | −130.1 | −124.0 | ||

| MTase | −121.3 | −112.3 | −109.5 | ||

| RdRp | −117.3 | −108.6 | −106.5 | ||

Kushenol A (408.49, 30, 3, 5, 4.71) |

Protease | −79.1 | −74.2 | −78.4 | Isolated from the roots of Sophora flavescens; shows antibacterial activity [62]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −125.4 | −117.6 | −113.6 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −137.0 | −128.6 | −122.5 | ||

| MTase | −128.9 | −120.9 | −116.2 | ||

| RdRp | −104.2 | −97.7 | −97.5 | ||

Neosilyhermin A (466.44, 34, 5, 9, 2.02) |

Protease | −82.1 | −73.7 | −78.1 | A constituent of milk thistle (Silybum marianum) [63]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −137.9 | −123.7 | −118.7 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −136.6 | −122.6 | −117.7 | ||

| MTase | −133.1 | −119.4 | −115.2 | ||

| RdRp | −109.2 | −98.0 | −97.8 | ||

Solophenol D (438.47, 32, 5, 7, 3.05) |

Protease | −110.5 | −101.2 | −100.5 | Isolated from propolis collected from the Solomon Islands; shows antibacterial activity [64]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −122.4 | −112.2 | −109.4 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −139.9 | −128.2 | −122.4 | ||

| MTase | −134.0 | −122.8 | −118.0 | ||

| RdRp | −104.4 | −95.6 | −96.0 | ||

Sophoraflavanone G (424.49, 31, 4, 6, 5.10) |

Protease | −80.8 | −74.8 | −79.0 | Isolated from the roots of Sophora flavescens; shows antibacterial activity [65]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −109.8 | −101.6 | −100.8 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −113.7 | −108.1 | −105.6 | ||

| MTase | −127.9 | −118.5 | −114.5 | ||

| RdRp | −104.9 | −97.2 | −97.2 | ||

| LIGNANS | |||||

(−)-Asarinin (354.35, 26, 0, 6, 2.70) |

Protease | −75.1 | −73.9 | −77.8 | Found in several species of Asarum, Boronia, and Zanthoxylum[54]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −109.2 | −107.4 | −104.8 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −123.0 | −121.0 | −115.7 | ||

| MTase | −126.4 | −124.3 | −118.4 | ||

| RdRp | −103.8 | −102.1 | −100.5 | ||

(7′R, 8S,8′R)-4,5-Dimethoxy-3′,4′-methylenodioxy-2,7′-cyclolignan-7-one (= Aristotetralone) (354.40, 26, 0, 5, 3.93) |

Protease | −66.0 | −64.9 | −70.6 | Isolated from Aristolochia chilensis; shows antiplasmodial activity [66]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −100.5 | −98.9 | −97.9 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −118.5 | −116.5 | −112.1 | ||

| MTase | −93.4 | −91.8 | −92.3 | ||

| RdRp | −115.5 | −113.6 | −109.8 | ||

(7R,8R,7′S,8′R)-4-Hydroxy-3,3′,5-trimethoxy-4′,5′-methylenedioxy-7,7′-epoxylignan (402.44, 29, 1, 7, 3.64) |

Protease | −95.9 | −90.4 | −91.9 | Isolated from Peperomia blanda; shows antitrypanosomal activity [67]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −103.6 | −97.7 | −97.9 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −126.4 | −119.1 | −115.4 | ||

| MTase | −109.1 | −102.8 | −102.1 | ||

| RdRp | −114.5 | −108.0 | −106.3 | ||

Di-O-demethylisoguaiacin (300.35, 22, 4, 4, 3.96) |

Protease | −65.2 | −67.8 | −72.0 | Isolated from Larrea tridentata; shows antiprotozoal activity [68]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −77.0 | −80/0 | −81.7 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −103.8 | −107.9 | −103.8 | ||

| MTase | −89.6 | −93.2 | −92.2 | ||

| RdRp | −114.4 | −118.9 | −112.6 | ||

Hibalactone (= Savinin) (352.34, 26, 0, 6, 3.60) |

Protease | −76.5 | −75.4 | −78.9 | A constituent of the needles of Juniperus sabina and Juniperus converta, the bark of Chloroxylon swietenia and Zanthoxylum nitidum[54]. Shows antiviral activity against severe acute respiratory syndrome associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) [69]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −116.6 | −114.9 | −110.7 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −148.3 | −146.2 | −135.8 | ||

| MTase | −114.7 | −113.1 | −109.2 | ||

| RdRp | −103.1 | −101.6 | −99.9 | ||

Kaerophyllin (368.38, 27, 0, 6, 3.57) |

Protease | −76.5 | −74.3 | −78.3 | Isolated from the roots of Chaerophyllum maculatum[70]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −115.6 | −112.3 | −109.0 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −145.8 | −141.5 | −132.6 | ||

| MTase | −103.2 | −100.2 | −99.2 | ||

| RdRp | −111.5 | −108.3 | −105.7 | ||

| PHENOLICS | |||||

7-(3,4-Dihydroxy-5-methoxyphenyl)-1-phenyl-4-hepten-3-one (326.39, 24, 2, 4, 4.80) |

Protease | −67.6 | −68.3 | −72.9 | A constituent of the rhizomes of Alpinia officinarum; shows antibacterial activity [71]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −108.5 | −109.7 | −106.0 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −124.3 | −125.7 | −118.7 | ||

| MTase | −118.7 | −120.0 | −114.2 | ||

| RdRp | −97.2 | −98.3 | −96.9 | ||

| RdRp | −119.7 | −105.8 | −104.5 | ||

Cimiciphenol (358.34, 26, 3, 7, 2.69) |

Protease | −88.1 | −86.3 | −88.1 | Found in the rhizome of black cohosh, Actaea racemosa (syn. Cimicifuga racemosa) [72]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −121.7 | −119.2 | −115.9 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −123.3 | −120.8 | −100.2 | ||

| MTase | −124.8 | −122.3 | −117.1 | ||

| RdRp | −99.9 | −97.9 | −97.4 | ||

Cimiracemate B (358.34, 26, 3, 7, 2.69) |

Protease | −91.7 | −89.8 | −90.9 | Found in the rhizome of black cohosh, Actaea racemosa (syn. Cimicifuga racemosa) [73]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −120.5 | −118.0 | −113.7 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −139.0 | −136.2 | −128.3 | ||

| MTase | −127.2 | −124.7 | −119.1 | ||

| RdRp | −107.0 | −104.9 | −103.1 | ||

Rosmarinic acid (360.32, 26, 5, 8, 2.24) |

Protease | −86.8 | −84.9 | −87.0 | Found in rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), lemon balm (Melissa officinalis), common sage (Salvia officinalis), and many other plant species [54]; shows antiviral activity [74]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −108.2 | −105.9 | −104.0 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −126.3 | −123.6 | −118.3 | ||

| MTase | −123.5 | −120.8 | −116.1 | ||

| RdRp | −96.9 | −94.8 | −95.0 | ||

Shikonofuran E (356.41, 26, 2, 5, 3.14) |

Protease | −95.4 | −93.7 | −93.9 | Isolated from the roots of Lithospermum erythrorhizon[75]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −113.0 | −110.9 | −107.8 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −135.8 | −133.3 | −125.9 | ||

| MTase | −115.0 | −112.9 | −109.4 | ||

| RdRp | −106.6 | −104.6 | −102.7 | ||

| QUINONES | |||||

Rhinacanthin D (408.40, 30, 1, 7, 2.83) |

Protease | −98.9 | −92.8 | −93.4 | Isolated from Rhinacanthus nasutus; shows antiviral activity [76]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −118.0 | −110.7 | −108.0 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −136.6 | −128.2 | −122.1 | ||

| MTase | −114.8 | −107.7 | −105.6 | ||

| RdRp | −96.3 | −90.4 | −91.5 | ||

| SESQUITERPENOIDS | |||||

Cinnamoylechinaxanthol (384.51, 28, 1, 4, 4.53) |

Protease | −76.8 | −73.6 | −77.9 | Isolated from the roots of Echinacea purpurea[77]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −115.4 | −110.5 | −107.9 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −123.1 | −117.8 | −113.8 | ||

| MTase | −110.9 | −106.1 | −104.3 | ||

| RdRp | −114.4 | −109.5 | −107.1 | ||

Lactucopicrin (410.42, 30, 2, 7, 1.63) |

Protease | −78.9 | −73.9 | −78.3 | Isolated from Lactuca spp. and Cichorium spp. [54]. Shows antiplasmodial activity [78]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −120.8 | −113.1 | −110.1 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −153.3 | −143.6 | −134.8 | ||

| MTase | −103.6 | −97.0 | −97.0 | ||

| RdRp | −109.3 | −102.4 | −101.4 | ||

| STEROIDS | |||||

Furost-5-ene-3,22,26,27-tetrol (= Hypoglaucin F aglycone) (448.64, 32, 4, 5, 3.48) |

Protease | −34.2 | −31.1 | −43.7 | Isolated from the rhizomes of Dioscorea collettii[79]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −105.3 | −95.7 | −96.7 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −106.8 | −97.1 | −97.8 | ||

| MTase | −112.9 | −102.7 | −102.3 | ||

| RdRp | −118.1 | −107.4 | −106.2 | ||

Tribufuroside I (aglycone) (464.64, 33, 4, 6, 3,45) |

Protease | −71.8 | −64.5 | −71.1 | Isolated from the fruits of Tribulus terrestris[80]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −109.6 | −98.5 | −99.0 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −106.3 | −95.5 | −96.5 | ||

| MTase | −110.7 | −99.5 | −99.8 | ||

| RdRp | −124.6 | −111.9 | −110.0 | ||

Trigoneoside I (aglycone) (450.65, 32, 4, 5, 4.06) |

Protease | −75.7 | −68.7 | −74.6 | Isolated from the seeds of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) [81]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −102.6 | −93.2 | −94.7 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −116.1 | −105.4 | −104.7 | ||

| MTase | −98.0 | −89.0 | −91.2 | ||

| RdRp | −125.5 | −113.9 | −111.6 | ||

| STILBENOIDS | |||||

Licoagrodione (356.37, 26, 3, 6, 3.08) |

Protease | −87.5 | −85.9 | −87.6 | Isolated from Glycyrrhiza glabra hairy root cultures; shows antimicrobial activity [82]. |

| Helicase (RNA site) | −115.8 | −113.7 | −110.0 | ||

| Helicase (ATP site) | −128.7 | −126.4 | −120.3 | ||

| MTase | −113.3 | −111.2 | −108.1 | ||

| RdRp | −111.2 | −109.2 | −106.4 |

MW = molecular weight (g/mol); NH = number of non-hydrogen atoms; HBD = number of hydrogen-bond-donating atoms; HBA = number of hydrogen-bond-accepting atoms; ClogP = calculated octanol/water partition coefficient.

Edock = Molegro “rerank” docking scores (kJ/mol).

E′ = Normalized docking score: E′ = 6.96 × Edock/MW⅓.

E′′ = Alternative normalized docking score: E′′ = Edock − 18.3 − Edock × NH/125.

3.1. Zika virus NS2B-NS3 protease

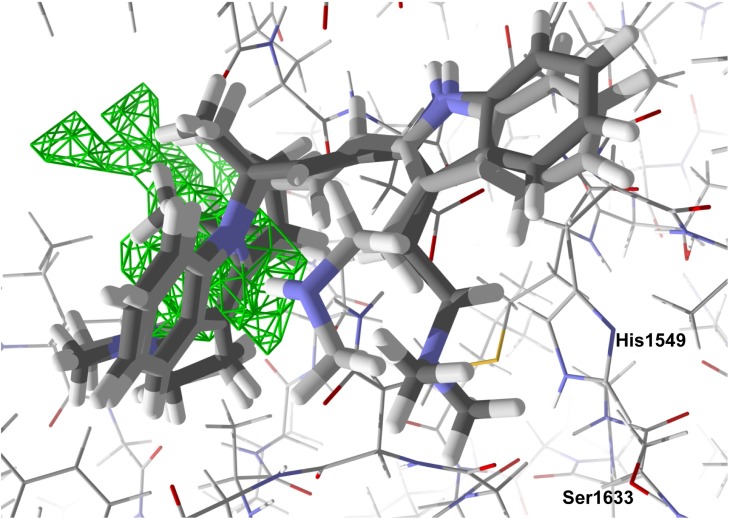

The homology modeled ZIKV NS2B-NS3 protease is a small (148 residues) protein. Most low-molecular-weight ligands docked into a small hydrophobic binding site bounded by Gln1572, Thr1664, Asn1650, Lys1571, and Ile1621. Phytochemical ligands with good docking scores with ZIKV NS2B-NS3 protease are listed in Table 2. Only two alkaloids obeyed Lipinski’s rule [38] and showed notable docking to ZIKV protease, the bis-indole alkaloids flinderole A and flinderole B. The flinderoles docked with ZIKV protease such that one of the indole moieties occupied the hydrophobic binding site, while the other indole, along with the amide side chain, was places near the active site histidine (His1549) (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Lowest-energy docked poses of flinderoles A and B with ZIKV NS2B-NS3 protease. The hydrophobic cavity is shown with green hashmarks.

The chalcones angusticornin B and kuraridin showed promising docking properties with ZIKV NS2B-NS3 protease (Table 2). The lowest-energy pose of the bis-hydroxyprenylated chalcone angusticornin B placed the hydroxyprenylated B-ring into the hydrophobic cavity, with none of the ligand occupying the active site of the protease Ser1633 and His1549 (Fig. 3 A). Kuraridin preferentially docked to ZIKV NS2B-NS3 protease placing the diprenyl-substituted A-ring into the hydrophobic cavity and the B-ring also not occupying the active site (Fig. 3B). Although the ligands in Table 2 did show relatively strong docking to ZIKV NS2B-NS3 protease, the docking energies are less than those for other ZIKV target proteins, likely a consequence of the small (42 Å3) binding pocket in the protease. Thus, it is unlikely that these ligands will exhibit selective protease inhibition.

Fig. 3.

Ligand-receptor interaction map of angusticornin B (panel A) and kuraridin (panel B) with the Zika virus NS2B-NS3 protease.

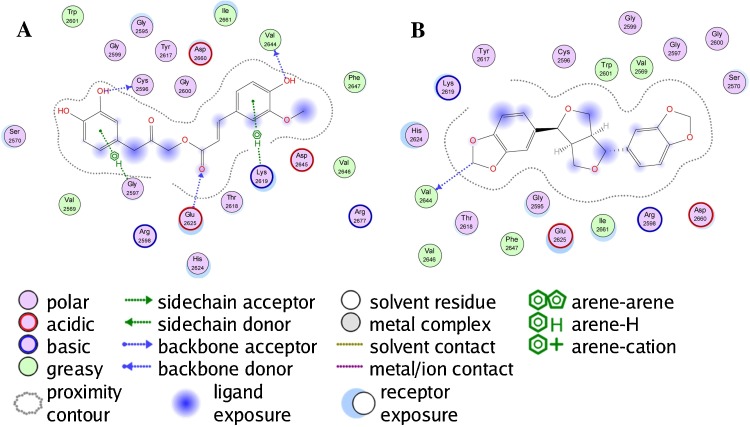

3.2. Zika virus NS3 helicase

The X-ray crystal structure of ZIKV helicase has recently been determined [23]. There are two binding sites for flavivirus NS3 helicases, an RNA binding site and an ATP binding site [83], [84]. Most phytochemical ligands showed more exothermic docking energies with the ATP site over the RNA site of ZIKV NS3 helicase. For example, the isoquinoline alkaloid cassiarin D showed very strong docking to the ATP site (Edock = −150.7 kJ/mol). In addition, cassiarin D showed some docking selectivity toward the ATP site of helicase (Fig. 4 A). Similarly, the flavonoids 3′-O-methyldiplacone and exiguaflavanone A, and the sesquiterpenoid lactucopicrin docked selectively with the ATP site of helicase. Several other phytochemical ligands (e.g., the aurones kanzonol V, the chalcones angusticornin B, balsacone B, and kanzonol Y, and the lignans hibalactone and kaerophyllin) also showed remarkably strong interactions with the ATP site of helicase. Interestingly, the bis-indole alkaloid 4,4′-dimethylisoborreverine was selective for the RNA site of ZIKV NS3 helicase (Fig. 4B). The intermolecular interactions between the ligands and the helicase protein are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Ligand-receptor interaction map of cassiarin D with the with the ATP binding site (panel A) and 4,4′-dimethylisoborreverine (panel B) and with the RNA binding site of the Zika virus NS3 helicase (PDB 5JMT [23]).

3.3. Zika virus NS5 methyltransferase

Non-structural protein 5 is made up of two domains. The N-terminal domain contains the methyltransferase (MTase) domain, while the C-terminus contains the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) domain. The methyltransferase domain is comprised of two binding sites, the GTP binding site and the SAM binding site [85]. The phytochemical ligands in this study docked preferentially to the GTP site rather than the SAM site.

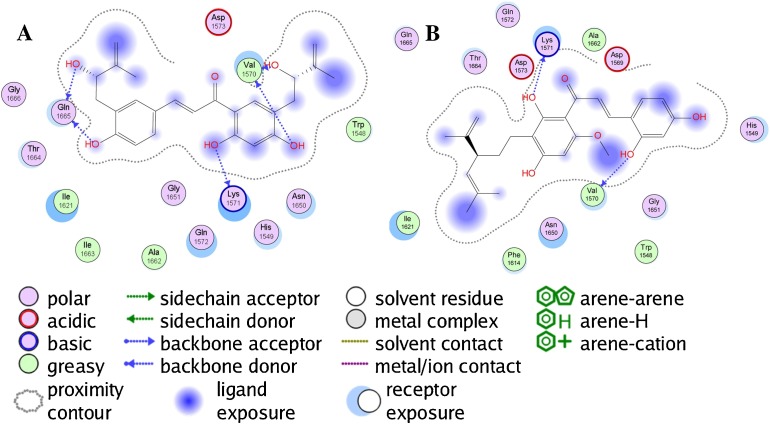

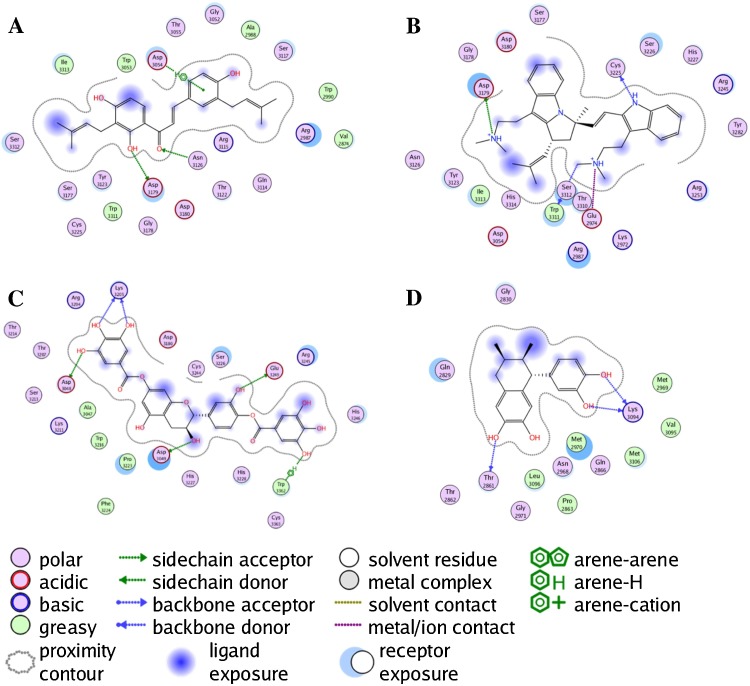

The best docking ligands for ZIKV NS5 MTase from this study were polyphenolic compounds with at least two phenolic groups, preferably connected with a flexible linker. Thus, for example, cimiphenol, cimiracemate B, and rosemarinic acid exhibited relatively strong docking energies. Prenyl substituents also decreased docking energies; the prenylated chalcones kanzonol Y and kuraridin showed excellent docking properties. Likewise, the prenylated aurone kanzonol V and the geranylated flavone solophenol D also showed strong docking to ZIKV MTase. Interestingly, the lignan (−)-asarinin showed good docking to MTase (Edock = −126.4 kJ/mol), but its epimer, (+)-sesamin, showed weaker docking (Edock = −101.1 kJ/mol). Key interactions between the phenolic ligands and the MTase binding site are Lys2619, Ile2661, Gly2959, Thr2618, and Glu2625 (see Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Protein-ligand interaction map between Zika virus NS5 methyltransferase and the lowest-energy docked pose of the phenolic ligand cimiracemate B (panel A) and the lignan (−)-asarinin (panel B).

3.4. Zika virus NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

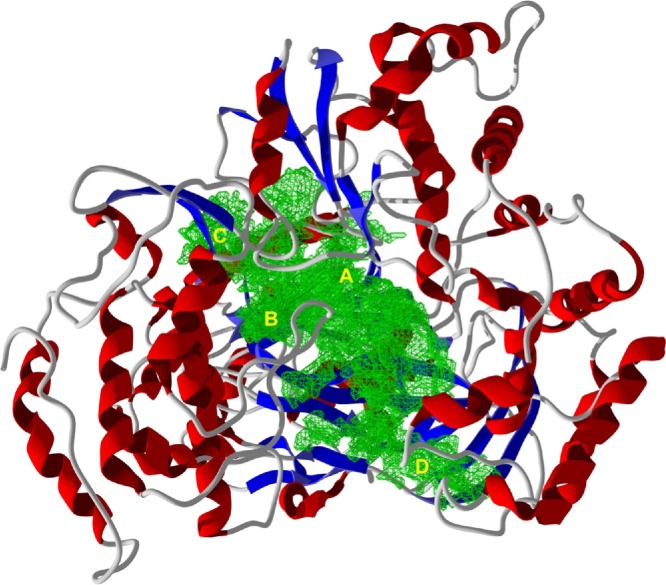

The ZIKV NS5 RdRp homology-modeled structure based on the Japanese encephalitis virus NS5 (PDB 4K6M) [30] has a very large binding cavity (∼2852 Å3). There were four major docking sites of phytochemical ligands with this protein structure (see Fig. 6 ), site A, with major interactions between the docked ligands and Asp3054, Asp3179, Tyr3123, Arg2987, and Ser3177; site B, with major interacting residues Trp3311, Arg3245, Ser3312, and Ser3226; site C, with residues Arg3245, His3246, His3227, His3228, and Trp3362; and site D, bounded by residues Met2970, Leu3096, Pro2863, and Gln2829.

Fig. 6.

Ribbon structure of Zika virus NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase homology model based on the Japanese encephalitis virus NS5 (PDB 4K6 M [30]). The binding cavity is shown in green with the preferred ligand docking sites, A–D.

Small hydrophobic ligands such as the monoterpenoids and naphthoquinones docked preferentially in sites C (58%) and D (38%). Large hydrophobic ligands, the triterpenoids, on the other hand, tended to concentrate in sites A (20%), B (51%), and C (18%). The best docking ligands to NIKV NS5 RdRp were aromatic ligands, particularly polyphenolics. The prenylated chalcone, 2′,4,4′-trihydroxy-3,3′-diprenylchalcone, docked preferentially into site A (Fig. 7 A) while the bis-indole alkaloid flinderole B docked into site B (Fig. 7B). The polyphenoic compound 4′,7-digalloylcatechin docked into site C (Fig. 7C), and the lignan di-O-demethylisoguaiacin docked into site D (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Protein-ligand interaction map between Zika virus NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and the lowest-energy docked pose of the prenylated chalcone, 2′,4,4′-trihydroxy-3,3′-diprenylchalcone (panel A), the bis-indole alkaloid flinderole B (panel B), the polyphenoic compound 4′,7-digalloylcatechin (panel C), and the lignan di-O-demethylisoguaiacin (panel D).

Notably, the homology model of ZIKV RNA-dependent RNA polymerase based on the West Nile virus template (PDB 2HFZ) has a much smaller binding cavity than the model based on the Japanese encephalitis virus NS5 template (PDB 4K6 M), 302 Å3 and 2852 Å3, respectively. Because of this, nearly all of the docking energies (2164 of the total 2263 ligands) were lower for the 4K6M model than the 2HFZ model; an average Edock difference of 11.8 kJ/mol per ligand. It would appear, based on these data, that the homology model based on WNV RdRp is a poorer model than that based on JEV.

4. Conclusions

The best docking phytochemical ligands were the polyphenolics, which generally docked strongly to several of the protein targets. The poorest docking ligands were the terpenoids, in particular the monoterpenoids, owing to their small size, and the triterpenoids, likely due to their paucity of functional groups.

There are several phytochemical ligands that had shown good selective docking properties and that are found in relatively common medicinal herbs. For example, balsacone B is found in the buds of balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera), kanzonol V is found in licorice root (Glycyrrhiza glabra), cinnamoylechinaxanthol is found in Echinacea root; cimiphenol is found in black cohosh (Actaea racemosa, syn. Cimicifuga racemosa); and rosemarinic acid is found in several common herbs including rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), lemon balm (Melissa officinalis), and common sage (Salvia officinalis). Hence, there are several common medicinal plants that may serve as antiviral agents themselves or ready sources of potential antivirals. We hope that this study encourages research into antiviral screening of medicinal plants and phytochemicals to identify antiviral agents and lead structures for structure-based design for new chemotherapeutics to treat Zika viral infections as well as other neglected tropical diseases.

Acknowledgment

This work was performed as part of the activities of the Research Network Natural Products against Neglected Diseases (ResNet-NPND), http://www.uni-muenster.de/ResNetNPND/index.html.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmgm.2016.08.011.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Shi P.Y. Calister Academic Press; Norfolk, UK: 2012. Molecular Virology and Control of Flaviviruses. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dick G.W., Kitchen S.F., Haddow A.J. Zika virus. I. Isolations and serological specificity. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1952;46:509–520. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(52)90042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayes E.B. Zika virus outside Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009;15:1347–1350. doi: 10.3201/eid1509.090442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musso D., Nilles E.J. and V.M. Cao-Lormeau: rapid spread of emerging Zika virus in the Pacific area. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014;20:O595–O596. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campos G.S., Bandeira A.C., Sardi S.I. Zika virus outbreak, Bahia, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:1885–1886. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.150847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodríguez-Morales A.J. Zika: the new arborvirus threat for Latin America. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2015;9:684–685. doi: 10.3855/jidc.7230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hennessey M., Fischer M., Staples J.E. Zika virus spreads to new areas −Region of the Americas, May 2015–January 2016. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016;65(3):55–58. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6503e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musso D., Roche C., Robin E., Nhan T., Teissier A., Cao-Lormeau V.M. Potential sexual transmission of Zika virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:359–361. doi: 10.3201/eid2102.141363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tetro J.A. Zika and microcephaly: causation, correlation, or coincidence? Microbes Infect. 2016;18:167–168. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oehler E., Watrin L., Larre P., Leparc-Goffart I., Lastère S., Valour F., Baudouin L., Mallet H.P., Musso D., Ghawche F. Zika virus infection complicated by Guillain-Barré syndrome−case report, French Polynesia, December 2013. Euro Surveill. 2014;19(9) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.9.20720. ID = 20720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliveira Melo A.S., Malinger G., Ximenes R., Szejnfeld P.O., Sampaio S.A., Bispo de Filippis A.M. Zika virus intrauterine infection causes fetal brain abnormality and microcephaly: tip of the iceberg? Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016;47:6–7. doi: 10.1002/uog.15831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ventura C.V., Maia M., Bravo-Filho V., Góis A.L., Belfort R. Zika virus in Brazil and macular atrophy in a child with microcephaly. Lancet. 2016;387:228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen E.E., Staples J.E., Meaney-Delman D., Fischer M., Ellington S.R., Callaghan W.M., Javieson D.J. Interim guidelines for pregnant women during a Zika virus outbreak −United States, 2016. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016;65(2):30–33. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6502e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomlinson S.M., Malmstrom R.D., Watowich S.J. New approaches to structure-based discovery of dengue protease inhibitors. Infect. Disord. Drug Targ. 2009;9:327–343. doi: 10.2174/1871526510909030327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoermer M.J., Chappell K.J., Liebscher S., Jensen C.M., Gan C.H., Gupta P.K., Xu W.J., Young P.R., Fairlie D.P. Potent cationic inhibitors of West Nile virus NS2B/NS3 protease with serum stability: cell permeability and antiviral activity. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:5714–5721. doi: 10.1021/jm800503y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steuber H., Kanitz M., Ehlert F.G.R., Diederich W.E. Recent advances in targeting dengue and West Nile virus proteases using small molecule inhibitors. Top. Med. Chem. 2015;15:93–142. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo D., Vasudevan S.G., Lescar J. The flavivirus NS2B-NS3 protease-helicase as a target for antiviral drug development. Antiviral Res. 2015;18:148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geiss B.J., Thompson A.A., Andrews A.J., Sons R.L., Gari H.H., Keenan S.M., Peersen O.B. Analysis of flavivirus NS5 methyltransferase cap binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;385:1643–1654. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong H., Zhang B., Shi P.Y. Flavivirus methyltransferase: a novel antiviral target. Antiviral Res. 2008;80:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falk S.P., Weisblum B. Aptamer displacement screen for flaviviral RNA methyltransferase inhibitors. J. Biomol. Screen. 2014;19:1147–1153. doi: 10.1177/1087057114533147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geiss B.J., Stahla H., Hannah A.M., Gari H.H., Keenan S.M. Focus on flaviviruses: current and future drug targets. Future Med. Chem. 2009;1:327–344. doi: 10.4155/fmc.09.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim S.P., Noble C.G., Shi P.Y. The dengue virus NS5 protein as a target for drug discovery. Antiviral Res. 2015;119:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian H., Ji X., Yang X., Xie W., Yang K., Chen C., Wu C., Chi H., Mu Z., Wang Z., Yang H. The crystal structure of Zika virus helicase: basis for antiviral drug design. Protein Cell. 2016;7:450–454. doi: 10.1007/s13238-016-0275-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerber P.R., Müller K. MAB: a generally applicable molecular force field for structure modelling in medicinal chemistry. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 1995;9:251–268. doi: 10.1007/BF00124456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J., Cieplak P., Kollman P.A. How well does a restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) model perform in calculating conformational energies of organic and biological molecules? J. Comp. Chem. 2000;21:1049–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Case D.A., Darden T.A., Cheatham T.E., Simmerling C.L., Wang J., Duke R.E., Luo R., Crowley M., Walker R.C., Zhang W., Merz K.M. University of California; San Francisco: 2008. Amber 10. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luo D., Wei N., Doan D.N., Paradkar P.N., Chong Y., Davidson A.D., Kotaka M., Lescar J., Vasudevan S.G. Flexibility between the protease and helicase domains of the dengue virus NS3 protein conferred by the linker region and its functional implications. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:18817–18827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.090936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Assenberg R., Mastrangelo E., Walter T.S., Verma A., Milani M., Owens R.J., Stuart D.I., Grimes J.M., Mancini E.J. Crystal structure of a novel conformational state of the flavivirus ns3 protein: implications for polyprotein processing and viral replication. J. Virol. 2009;83:12895–12906. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00942-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erbel P., Schiering N., D’Arcy A., Renatus M., Kroemer M., Lim S.P., Yin Z., Keller T.H., Vasudevan S.G., Hommel U. Structural basis for the activation of Flaviviral NS3 proteases from dengue and West Nile virus. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:372–373. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu G., Gong P. Crystal Structure of the full-length Japanese encephalitis virus NS5 reveals a conserved methyltransferase-polymerase interface. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003549. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malet H., Egloff M.P., Selisko B., Butcher R.E., Wright P.J., Roberts M., Gruez A., Sulzenbacher G., Vonrhein C., Bricogne G., Mackenzie J.M., Khromykh A.A., Davidson A.D., Canard B. Crystal structure of the RNA polymerase domain of the West Nile virus non-structural protein 5. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:10678–10689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomsen R., Christensen M.H. MolDock: a new technique for high-accuracy molecular docking. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:3315–3321. doi: 10.1021/jm051197e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halgren T.A. Merck molecular force field. I. Basis form, scope, parameterization, and performance of MMFF 94. J. Comput. Chem. 1996;17:490–519. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pan Y., Huang H., Cho S., MacKerell A.D. Consideration of molecular weight during compound selection in virtual target-based database screening. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003;43:267–272. doi: 10.1021/ci020055f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Y.M., Shen T.W. A pharmacophore-based evolutionary approach for screening selective estrogen receptor modulators. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 2005;59:205–220. doi: 10.1002/prot.20387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abad-Zapatero C., Metz J.T. Ligand efficiency indices as guideposts for drug discovery. Drug Disc. Today. 2005;10:464–469. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03386-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carta G., Knox A.J.S., Lloyd D.G. Unbiasing scoring functions: a new normalization and rescoring strategy. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007;47:1564–1571. doi: 10.1021/ci600471m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipinski C.A., Lombardo F., Dominy B.W., Feeney P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012;64:4–17. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tillequin F., Koch M., Bert M., Sevenet T. Plantes de Nouvelle Calédonie. LV. Isoborrévérine et borrévérine: alcaloïdes bis-indoliques de Flindersia fournieri. J. Nat. Prod. 1979;42:92–95. doi: 10.1021/np50001a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandez L.S., Buchanan M.S., Carroll A.R., Quinn Y.J., Quinn R.J., Avery V.M. Flinderoles A–C: antimalarial bis-indole alkaloids from Flindersia species. Org. Lett . 2009;11:329–332. doi: 10.1021/ol802506n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oshimi S., Deguchi J., Hirasawa Y., Ekasari W., Widyawaruyanti A., Wahyuni T.S., Zaini N.C., Shirota O., Morita H. Cassiarins C-E, antiplasmodial alkaloids from the flowers of Cassia siamea. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:1899–1901. doi: 10.1021/np9004213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu T.S., Shi L.S., Kuo S.C. Alkaloids and other constituents from Tribulus terrestris. Phytochemistry. 1999;50:1411–1415. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fukai T., Cai B., Maruno K., Miyakawa Y., Konishi M., Nomura T. An isoprenylated flavanone from Glycyrrhiza glabra and rec-assay of licorice phenols. Phytochemistry. 1998;49:2005–2013. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asada Y., Li W., Yoshikawa T. The first prenylated biaurone: licoagrone from hairy root cultures of Glycyrrhiza glabra. Phytochemistry. 1999;50:1015–1019. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuete V., Simo I.K., Ngameni B., Bigoga J.D., Watchueng J., Kapguep R.N., Etoa F.X., Tchaleu B.N., Beng V.P. Antimicrobial activity of the methanolic extract: fractions and four flavonoids from the twigs of Dorstenia angusticornis Engl. (Moraceae) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;112:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lavoie S., Legault J., Simard F., Chiasson E., Pichette A. New antibacterial dihydrochalcone derivatives from buds of Populus balsamifera. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013;54:1631–1633. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin S., Fan C.Q., Wang Y., Dong L., Yue J.M. Antibacterial prenylflavone derivatives from Psoralea corylifolia: and their structure-activity relationship study. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;12:4387–4392. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Narender T., Shweta K., Tanvir M.S., Rao K. Srivastava, Puri S.K. Prenylated chalcones isolated from Crotalaria genus inhibits in vitro growth of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:2453–2455. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hatayama K., Komatsu M. Studies on the constituents of Sophora species. V. Constituents of the root of Sophora angustifolia Sieb. et Zucc. (2) Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1971;19:2126–2131. doi: 10.1248/yakushi1947.90.4_463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan B.C.L., Yu H., Wong C.W., Lui S.L., Jolivalt C., Ganem-Elbaz C., Paris J.M., Morleo B., Litaudon M., Lau C.B.S., Ip M., Fung K.P., Leung P.C., Han Q.B. Quick identification of kuraridin: a noncytotoxic anti-MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) agent from Sophora flavescens using high speed counter-current chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B. 2012;880:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim S.J., Son K.H., Chang H.W., Kang S.S., Kim H.P. Tyrosinase inhibitory prenylated flavonoids from Sophora flavescens. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2003;26:1348–1350. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kwon H.J., Jeong J.H., Lee S.W., Ryu Y.B., Jeong H.J., Jung K., Lim J.S., Cho K.O., Lee W.S., Rho M.C., Park S.J. In vitro anti-reovirus activity of kuraridin isolated from Sophora flavescens against viral replication and hemagglutination. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015;128:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li W., Asada Y., Yoshikawa T. Flavonoid constituents from Glycyrrhiza glabra hairy root cultures. Phytochemistry. 2000;55:447–456. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00337-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.CRC Press Boca Raton; Florida, USA: 2015. Dictionary of Natural Products on DVD version 24:2. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kouam J., Mabeku L.B.K., Kuiate J.R., Tiabou A.T., Fomum Z.T. Antimicrobial glycosides and derivatives from roots of Picralima nitida. Int. J. Chem. 2011;3:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Šmejkal K., Chudík S., Klouček P., Marek R., Cvačka J., Urbanová M., Ondřej J., Kokoška L., Šlapetová T., Holubová P., Zima A., Dvorská M. Antibacterial C-geranylflavonoids from Paulownia tomentosa fruits. J. Nat. Prod. 2008;71:706–709. doi: 10.1021/np070446u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salem M.M., Capers J., Rito S., Werbovetz K.A. Antiparasitic activity of C-geranyl flavonoids from Mimulus bigelovii. Phytother. Res. 2011;25:1246–1249. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Šmejkal K., Svačinová J., Šlapetov T., Schneiderová K., Dall’Acqua S., Innocenti G., Závalová V., Kollár P., Chudík S., Marek R., Julínek O., Urbanová M., Kartal M., Csöllei M., Doležal K. Cytotoxic activities of several geranyl-substituted flavanones. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:568–572. doi: 10.1021/np900681y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barrett M.L., Scutt A.M., Evans F.J. Cannflavin A and B: prenylated flavones from Cannabis sativa L. Experientia. 1986;42:452–453. doi: 10.1007/BF02118655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chanphen R., Thebtaranonth Y., Wanauppathamkul S., Yuthavong Y. Antimalarial principles from Artemisia indica. J. Nat. Prod. 1998;61:1146–1147. doi: 10.1021/np980041x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mitscher L.A., Gollapudi S.R., Khanna I.K., Drake S.D., Hanumaiah T., Ramaswam T., Rao K.V.J. Antimicrobial agents from higher plants: activity and structural revision of flemiflavanone-D from Flemingia stricta. Phytochemistry. 1985;24:2885–2887. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kuroyanagi M., Arakawa T., Hirayama Y., Hayashi T. Antibacterial and antiandrogen flavonoids from Sophora flavescens. J. Nat. Prod. 1999;62:1595–1599. doi: 10.1021/np990051d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fiebig M., Wagner H. Neue antihepatotoxisch wirksame Flavonolignane aur einer weiβblühenden Silybum-Varietät. Planta Med. 1984;50:310–313. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-969717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Inui S., Hosoya T., Shimamura Y., Masuda S., Ogawa T., Kobayashi H., Shirafuji K., Moli R.T., Kozone I., Shin-ya K., Kumazawa S. Solophenols B-D and solomonin. New prenylated polyphenols isolated from propolis collected from the Solomon Islands and their antibacterial activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:11765–11770. doi: 10.1021/jf303516w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cha J.D., Moon S.E., Kim J.Y., Jung E.K., Lee Y.S. Antibacterial activity of sophoraflavanone G isolated from the roots of Sophora flavescens against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Phytother. Res. 2009;23:1326–1331. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Andrade-Neto V.F., da Silva T., Lopes L.M.X., do Rosário V.E., Varotti F.P., Krettli A.U. Antiplasmodial activity of aryltetralone lignans from Holostylis reniformis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:2346–2350. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01344-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Felippe L.G., Baldoqui D.C., Kato M.J., Bolzani V.S., Guimarães E.F., Cicarelli R.M.B., Furlan M. Trypanocidal tetrahydrofuran lignans from Peperomia blanda. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:445–450. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schmidt T.J., Rzeppa S., Kaiser M., Brun R. Larrea tridentata −absolute configuration of its epoxylignans and investigations on its antiprotozoal activity. Phytochem. Lett. 2012;5:632–638. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wen C.C., Kuo Y.H., Jan J.T., Liang P.H., Wang S.Y., Liu H.G., Lee C.K., Chang S.T., Kuo C.J., Lee S.S., Hou C.C., Hsiao P.W., Chien S.C., Shyur L.F., Yang N.S. Specific plant terpenoids and lignoids possess potent antiviral activities against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:4087–4095. doi: 10.1021/jm070295s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mikaya G.A., Turabelidze D.G., Kemertelidze E.P., Wulfson N.S. Kaerophyllin: a new lignan from Chaerophyllum maculatum. Planta Med. 1981;43:378–380. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang B.B., Dai Y., Liao Z.X., Ding L.S. Three new antibacterial active diaryheptanoids from Alpinia officinarum. Fitoterapia. 2010;81:948–952. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kruse S.O., Löhning A., Pauli G.F., Winterhoff H., Nahrstedt A. Fukiic and piscidic acid esters from the rhizome of Cimicifuga racemosa and the in vitro estrogenic activity of fukinolic acid. Planta Med. 1999;65:763–764. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stromeier S., Petereit F., Nahrstedt A. Phenolic esters from the rhizomes of Cimicifuga racemosa do not cause proliferation effects in MCF-7 cells. Planta Med. 2005;71:495–500. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-864148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Parnham M.J., Kesselring K. Rosmarinic acid. Drugs Future. 1985;10:756–757. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yoshizaki F., Hisamichi S., Kondo Y., Sato Y., Nozoe S. Studies on shikon. III. new furylhydroquinone derivatives, shikonofurans A, B, C, D and E, from Lithospermum erythrorhizon Sieb. et Zucc. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1982;30:4407–4411. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sendl A., Chen J.L., Jolad S.D., Stoddart C., Rozhon E., Kernan M., Nanakorn W., Balick M. Two new naphthoquinones with antiviral activity from Rhinacanthus nasutus. J. Nat. Prod. 1996;59:808–811. doi: 10.1021/np9601871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bauer R.F.X., Khan I.A., Lotter H., Wagner H., Wray V. Structure and stereochemistry of new sesquiterpene esters from Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1985;68:2355–2358. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bischoff T.A., Kelley C.J., Karchesy Y., Laurantos M., Nguyen-Dinh P., Arefi A.G. Antimalarial activity of lactucin and lactucopicrin: sesquiterpene lactones isolated from Cichorium intybus L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004;95:455–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hu K., Dong X.S., Kobayashi H., Iwasaki S. A furostanol glycoside from rhizomes of Dioscorea collettii var hypoglauca. Phytochemistry. 1997;44:1339–1342. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xu T., Xu Y., Liu Y., Xie S., Si Y., Xu D. Two new furostanol saponins from Tribulus terrestris L. Fitoterapia. 2009;80:354–357. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yoshikawa M., Murakami T., Komatsu H., Murakami N., Yamahara J., Matsuda H. Medicinal foodstuffs. IV. fenugreek seed (1): structures of trigoneosides Ia, Ib, IIa, IIb, IIIa, IIIb, new furostanol saponins from the seeds of Indian Trigonella foenum-graecum L. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1997;45:81–87. doi: 10.1248/cpb.45.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li W., Asada Y., Yoshikawa T. Antimicrobial flavonoids from Glycyrrhiza glabra hairy root cultures. Planta Med. 1998:746–747. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Luo D., Xu T., Watson R.P., Scherer-Becker D., Sampath A., Jahnke W., Yeong S.S., Wang C.H., Lim S.P., Strongin A., Vasudevan S.G., Lescar J. Insights into RNA unwinding and ATP hydrolysis by the flavivirus NS3 protein. EMBO J. 2008;27:3209–3219. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Belon C.A., Frick D.N. Helicase inhibitors as specifically targeted antiviral therapy for hepatitis C. Future Virol. 2009;4:277–293. doi: 10.2217/fvl.09.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Noble C.G., Shi P.Y. Structural biology of dengue virus enzymes: towards rational design of therapeutics. Antiviral Res. 2012;96:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.