Abstract

Mouse hepatitis virus A59 (MHV-A59) is a representative member of the genus betacoronavirus within the subfamily Coronavirinae, which infects the liver, brain and respiratory tract. Through different inoculation routes, MHV-A59 can provide animal models for encephalitis, hepatitis and pneumonia to explore viral life machinery and virus-host interactions. In viral replication, non-structural protein 5 (Nsp5), also termed main protease (Mpro), plays a dominant role in processing coronavirus-encoded polyproteins and is thus recognized as an ideal target of anti-coronavirus agents. However, no structure of the MHV-A59 Mpro has been reported, and molecular exploration of the catalysis mechanism remains hindered. Here, we solved the crystal structure of the MHV-A59 Mpro complexed with a Michael acceptor-based inhibitor, N3. Structural analysis revealed that the Cβ of the vinyl group of N3 covalently bound to C145 of the catalytic dyad of Mpro, which irreversibly inactivated cysteine protease activity. The lactam ring of the P1 side chain and the isobutyl group of the P2 side chain, which mimic the conserved residues at the same positions of the substrate, fit well into the S1 and S2 pockets. Through a comparative study with Mpro of other coronaviruses, we observed that the substrate-recognition pocket and enzyme inhibitory mechanism is highly conservative. Altogether, our study provided structural features of MHV-A59 Mpro and indicated that a Michael acceptor inhibitor is an ideal scaffold for antiviral drugs.

Keywords: Mouse hepatitis virus A59, Crystal structure, Main protease, N3

Highlights

-

•

The crystal structure of MHV-A59 Mpro in complex with an inhibitor was determined.

-

•

The Michael acceptor N3 was found to be an irreversible inhibitor targeting the substrate binding pocket of MHV-A59 Mpro.

-

•

The complex structure revealed the crucial residues for inhibitor recognition.

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are a large group of enveloped positive-strand RNA viruses that can infect a wide range of species, including animals and humans, causing respiratory, hepatic and gastrointestinal illnesses [1]. CoVs have been divided into four main genera [2]: alphacoronavirus, which include animal pathogens, such as porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) and feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV) as well as human CoV NL63 (HCoV-NL63) and human CoV 229E (HCoV-229E); betacoronavirus, which also include pathogens of veterinary relevance, such as bovine coronavirus (BCoV), equine coronavirus (ECoV), and mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) as well as human CoV HKU1 (HCoV-HKU1), human CoV OC43 (HCoV-OC43), SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV); gammacoronavirus, which thus far include only avian coronaviruses, such as infectious bronchitis virus (IBV); and deltacoronavirus [3], a newly discovered genus that includes Bulbul coronavirus HKU11. The betacoronavirus can further be divided into 4 subgroups, each containing different HCoVs. The betacoronavirus not only contain pathogens causing severe respiratory syndrome in humans and animals but also carry a high risk of interspecies transmission from zoonotic reservoirs to humans. Both features make them a research hotspot.

MHV, belonging to betacoronavirus subgroup A, is a natural pathogen that specifically infects mice. Through different inoculation routes, such as the liver, gastrointestinal tract, and central nervous system (CNS), MHV can cause a wide range of diseases [4]. MHV infection of the mouse is considered to be one of the best animal models for the study of virus-host interactions [[5], [6], [7]]. MHV-A59 is a commonly used laboratory strain and thus provides animal models for hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis-like disease, encephalitis and demyelinating diseases [8,9]. The MHV-A59 genome is 32 kb in length and encodes two large polyproteins (pp1a and pp1ab) and several structural proteins, including nucleocapsid protein (N), envelope protein (E), spike protein (S) and matrix protein (M), in addition to a variety of accessory proteins. The two polyproteins need to be cleaved into 16 non-structural proteins (Nsps), which then assemble into the replication-transcription complex required for genome replication. Nsp5, also termed 3CL protease or main protease (Mpro), mediates proteolysis at 11 distinct cleavage sites, and is essential for virus replication. Due to its high conservation and low mutation or recombination rates, Mpro is thought to be a potential target for wide-spectrum inhibitor design.

Owing to its dominant and vital role in virus fitness and viral growth, numerous studies on Mpro have been reported. On the one hand, the fundamental molecular catalytic mechanism was unraveled by studies on the crystal structure of Mpro in complex with peptide substrate analogs [10,11]. Mpros were observed to exhibit a conserved three-domain structure. Domain I and domain II form a chymotrypsin-like fold for proteolysis, while domain III mainly participates in the formation of homodimers [12]. In the catalytic site, the catalytic dyad and potential substrate-binding pockets (S1—S5) were discovered [13,14]. On the other hand, the regulation of Mpro activity was investigated to gain a deeper understanding of the cleavage mechanism. First, it was found that the protease activity of Mpro could be related to its homodimerization in some way [15,16]. Then, long-distance communication was identified as a temperature-sensitive defect mutant in V184 or F219 could be readily recovered by a second-site mutation (S133 N or H134Y) [17,18]. Interestingly, all of these residues are distant from the catalytic site, substrate-binding pockets and dimerization interface.

Due to the lack of the structure of Mpro, the underlying mechanism for the regulation of protease activity and replication remains largely unclarified. In this study, we introduce some mutations to improve the biophysical and biochemical properties of MHV-A59 Mpro and thus obtain the crystal structure of the Mpro in complex with N3, a synthetic peptidomimetic inhibitor. Detailed structural studies will lead us to better understand its allosteric mechanism and provide a structural basis for rational drug design.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cloning and site-directed mutagenesis

The coding sequence for MHV-A59 main protease was synthetized and cloned into a self-constructed vector, PET-28b-sumo, using the BamHI and XhoI restriction sites. The L284F mutation was introduced into this plasmid by site-directed mutagenesis using an Easy site-directed mutagenesis kit (Transgen, Beijing, China). On the basis of this construct, deletion of S46 and A47 was introduced by overlapping extension PCR. Both recombinant plasmids were verified by sequencing.

2.2. Protein expression and purification

The plasmid was transformed into BL21 (DE3) E. coli strain. The strains were grown in LB broth containing 100 μg/mL kanamycin at 37 °C to an OD600 of ∼0.6. Protein expression was then induced by adding 0.5 mM IPTG and further cultured at 16 °C for 16 h. The cells were harvested and followed by sonication for lysis. Cell lysate was then prepared using centrifugation (12,000 g, 50 min, 4 °C). Ni-NTA affinity resin (GE Healthcare, USA) was used to capture the 6*His- & SUMO-tagged target proteins in lysate and SUMO tag was removed through on-column cleavage using SUMO protease (ULP) at 4 °C for 18 h. The resulting protein of interest was then applied to a HiTrap Q column (GE Healthcare, USA) in a linear gradient from 0 mM to 1,000 mM NaCl with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 10% glycerol. The target protein was collected and further purified using a Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare, USA) in a buffer consisting of 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) and 150 mM NaCl.

2.3. Crystallization

The purified Mpro-L284F-ΔS46A47 protein was supplemented with 10% DMSO and concentrated to 1 mg/mL using Thermo iCON concentrators. Inhibitor N3, dissolved in 100% DMSO to a final concentration of 10 mM as a stock, was added to the purified protein at a molar ratio of 3:1. After incubation at 4 °C for 4 h, the protein complex was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min and then concentrated to 10 mg/mL in a buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl and 2 mM DTT. Using microbatch-under-oil method, best crystals were obtained after two days under conditions containing 0.1 M sodium acetate trihydrate (pH 4.4–4.6) and 8%–10% w/v polyethylene glycol 4,000.

2.4. X-ray data collection and structure determination

The crystals were cryoprotected in a solution containing 0.1 M sodium acetate trihydrate (pH 4.6), 8% w/v polyethylene glycol 4,000 and 20% glycerol and then mounted in a nylon loop and flash cooled in a nitrogen stream at 100 K. The X-ray diffraction data sets were collected using a CCD detector on beamline BL-17B of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF). All intensity data were indexed, integrated and scaled with the HKL-2000 package [19].

The structure of MHV-A59 Mpro was determined by molecular replacement (MR) using the model of HKU1 Mpro (PDB ID 3D23) and the Programme Phaser [20]. The refinement was performed in Phenix.refine [21] with cycles of manual rebuilding in Coot [22]. The structure was refined to a resolution of 2.65 Å. The collection and refinement statistics are shown in Table 1 . The accession code in the Protein Data Bank is 6JIJ. Due to the deletion at S46 and A47, the numbers of amino acids, which are greater than 45 in our PDB file, need to be corrected by adding 2.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics.

| Data | Value for the Mpro-L284F-ΔS46A47 + N3 complex |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97854 |

| Space group | C2 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 167.8, 64.0, 118.0 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.0, 126.0, 90.0 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.0–2.65 (2.70–2.65)a |

| Total No. of reflections | 98,145 |

| No. of unique reflections | 29,741 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 (99.5) |

| Redundancy | 3.3 (3.0) |

| 〈 I/σ(I)〉 | 15.2 (2.1) |

| Rmerge (%) | 7.1 (43.0) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 33.95–2.65 (2.74–2.65) |

| No. of unique reflections (working set) | 29707 (2855) |

| No. of unique reflections (test) | 1502 (136) |

| Rwork (%) | 22.5 (29.0) |

| Rfree (%) | 26.8 (35.7) |

| Number of non-hydrogen atoms | 7002 |

| Protein | 6844 |

| Water | 11 |

| Ligand | 147 |

| B-factors | 65.8 |

| Protein | 61.1 |

| Water | 55.2 |

| Ligand/ion | 72.9 |

| RMSDs | |

| Bonds lengths (Å) | 0.004 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.77 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 93.8 |

| Ramachandran allowed (%) | 6.2 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0.0 |

Numbers in the brackets are for the highest resolution shell (the same below).

2.5. Enzymatic activity and inhibition assays

An enzymatic assay was performed by continuous kinetic assays in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.3) and 1 mM EDTA using the fluorogenic substrate MCA-AVLQSGFR-Lys(Dnp)-Lys-NH2 (>95% purity, GL Biochem Shanghai Ltd., Shanghai, China) as previously reported [23]. The reaction was initiated by adding 10 μL of substrate (final concentration spanning 2.5–40 μM) to 90 μL of protease solution (final protease concentration of 0.5 μM). In inhibition assay, substrate was mixed with N3 (final substrate concentration was 30 μM and N3 final concentration spanned 40–500 nM). Fluorescence intensity was then monitored at a speed of 3 s/1 measurement at 30 °C using a Fluoroskan Ascent instrument (Thermo Scientific, USA) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 320 nm and 405 nm, respectively. Kinetic parameters, including K m and k cat of Mpro-L284F and Mpro-L284F-ΔS46A47 and K i and k 3 for the N3 inhibitor, were determined from the methods described in detail in previous work [23] with GraphPad Prism 6.0 software.

3. Result and discussion

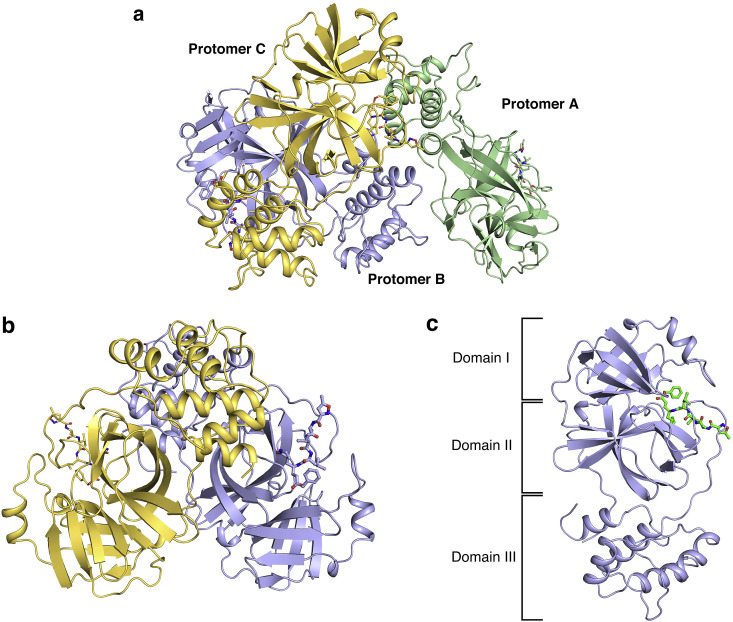

3.1. Overall structure

One asymmetric unit was occupied by three protein molecules (denoted as A, B, and C), with one N3 molecule per protomer (Fig. 1 a). Among them, protomer B and protomer C formed a homodimer, which was typical for CoV Mpros, while protomer A dimerized with the counterpart from the adjacent symmetry-related unit (Fig. 1b). All protomers displayed a three-domain (I to III) architecture: domain I (residues 8–100) and domain II (residues 101–183) together constituted chymotrypsin-like folds, while domain III (residues 200–303) exhibited five antiparallel α-helices arranged into a large globular cluster. The substrate-binding site was situated in the cleft between domain I and domain II. The catalytic dyad, composed of C145 and H41, was in the center of the substrate-binding site. The whole pocket comprised two featured deeply buried sites (S1 and S2) and several solvent-exposed sites (S3, S4, and S5) for the accommodation of different side chains in the substrate. Domain III was located right under domain II with a connected loop and contributed mainly to homodimer formation (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, F284 was located in the loop region in domain III and close to residues at the dimer interface. Interestingly, a temperature-sensitive suppressor is also situated nearby.

Fig. 1.

Structural overview of MHV-A59 Mpro.

(a) Overview of three protomers (A, pale green; B, light blue; C, yellow orange) in one asymmetric unit. Protomers are shown as cartoon diagrams, and N3 inhibitors are shown as sticks. (b) Overview of the homodimer in one asymmetric unit (B, light blue; C, yellow orange). Protomers are shown as cartoon diagrams, and N3 inhibitors are shown as sticks. (c) Overview of one monomer unit of the Mpro-inhibitor complex. Mpro is shown as a light blue cartoon, and the synthetic inhibitor is shown as green sticks. The three domains are labeled. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

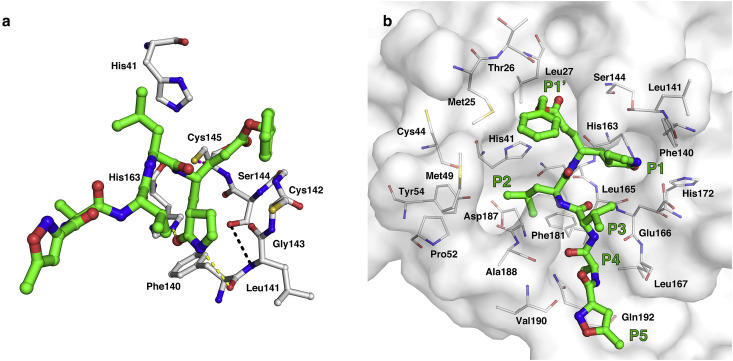

3.2. Michael acceptor and catalytic dyad

In numerous structural studies of CoV Mpro, N3, a well-designed Michael acceptor inhibitor, is frequently used to capture the transition state during the proteolysis process. The detailed mechanism is shown in the equation:

First, the inhibitor and the enzyme form a reversible complex (EI) under the equilibrium-binding constant K i. Then, the cysteine situated at the enzyme active site undergoes nucleophilic attack on the reactive atom of the inhibitor, leading to formation of a stable covalent bond (E-I). The determined K i and k 3 revealed a potent inhibition of MHV-A59 Mpro by N3 (Table 2 ). In our inhibitor-bound MHV-A59 Mpro structure, we observed a clear and continuous electron density between the Cβ of the vinyl group of N3 and the Sγ atom of C145, which confirms the formation of a covalent bond. The intermediate state is stabilized by H41 of the catalytic dyad and the oxyanion loop from F140 to C145 in which the backbone amides form an oxyanion hole (Fig. 2 a). The conformation of the oxyanion loop is tightened through the internal hydrogen bond between the side chain oxygen of S144 and the backbone nitrogen of L141. The correct position of the oxyanion loop is maintained by the following interactions: (i) a hydrogen bond between the backbone oxygen atom of F140 and the amide group nitrogen atom of the P1 side chain; (ii) a hydrogen bond between the oxygen atom of the P1 side chain and the imidazole ring Nε2 of H163; and (iii) hydrophobic stacking between the imidazole ring of H163 and the benzene ring of F140. Therefore, the P1 side chain helps to strengthen the hydrophobic stacking between H163 and F140 by forming hydrogen bonds with these residues and thus maintain the oxyanion loop in the proper position.

Table 2.

Enzyme activity and N3 inhibition data for MHV-A59 Mpro.

| Virus Mpro | Km (μM) | kcat (S−1) | Inhibitor N3 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki (μM) | k3 (10−3٠S−1) | |||

| MHV-A59-L284F | 57.31 ± 6.41 | 0.76 ± 0.06 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 57.02 ± 5.11 |

| MHV-A59-L284F-ΔS46A47 | 40.23 ± 5.33 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 76.84 ± 8.88 |

Fig. 2.

Interaction pattern between the inhibitor N3 and MHV-A59 Mpro.

(a) Stereo view of the interaction between N3 and the catalytic dyad. Residues and the N3 inhibitor are shown as sticks, and the covalent bond between N3 and C145 is shown by the magenta dashed line. The hydrogen bonds between the oxyanion loop and the P1 side chain are shown by the yellow dashed lines. The hydrogen bond inside the oxyanion loop is shown by the black dashed line. (b) Detailed view of N3 and the substrate-binding pocket, shown in stereo representation. The inhibitor is shown as green sticks, and the crucial residues of Mpro are shown as white sticks. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.3. P1 position

Since the lactam ring of the P1 side chain plays a crucial role in the catalytic process, glutamine seems to be the most competitive residue at the P1 position of the Mpro substrate. According to an analysis of the MHV-A59 genome sequence, we found that all 11 Mpro cleavage sites possess glutamine at the P1 position. Such a strong preference for glutamine is also a common feature in most CoV Mpros. In our structure, the S1 pocket constituted by F140, L141, S144, H163, E166 and H172 suitably accommodated the N3 lactam ring (Fig. 2b). The protruding lactam ring formed hydrogen bonds to (i) the aforementioned imidazole ring Nε2 of H163 and backbone oxygen atom of F140; (ii) the side chain Oε1 of E166 at a distance of 2.5 Å. Compared to those of other CoVs, the S1 pocket volume of MHV-A59 is similar to that of HCoV-HKU1, which is smaller than those of IBV and SARS-CoV. The size reduction of the S1 pocket is mainly attributed to a 90° upward bending of loop L167-C171. In HCoV-HKU1, the smaller S1 pocket could better accommodate the smaller imidazole ring of histidine at P1 of the nsp13-14 cleavage site. However, for MHV-A59, such a smaller S1 pocket is not that necessary because no substitution is observed at the P1 position.

3.4. P2 position

Based on a comparison of the protease recognition sites of the MHV-A59 PP1ab genome performed previously, we found that Mpro generally prefers a hydrophobic residue at the P2 position, which is also reported for nearly all CoVs. Although leucine/methionine are the most abundant, many other alternative residues, such as valine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, and proline, are also observed, which might imply less stringency of P2 specificity. The inhibitor N3 bears an aliphatic isobutyl group at the P2 site that mimics the leucine side chain. In our complex structure, the large hydrophobic side chain of P2 deeply protrudes into the buried S2 pocket via hydrophobic interactions with the side chains of H41, P52, and Y54 and is well accommodated onto the Van der Waals surface of the pocket (Fig. 2b). Residues constituting the complete S2 pocket also include L165, D187, A188, Q189, and S45—N51, which form a group-specific lid arranged as a short 310 helical region. It is worth mentioning that the deletion at S46 and A47 lead to a reduction in lid volume, which makes the pocket partially exposed to solvent. In combination with the enzymology data we measured, we found that this deletion lowered the K m and k cat to an acceptable degree (Table 2).

3.5. P3, P4 and P5 positions

With the exception of a strong preference at the P1/P2 residue, the P3 residue of cleavage sites exhibited no specificity for any particular side chains among CoV Mpros. This is consistent with the observation that the isopropyl group of the P3 side chain is solvent exposed in all three protomers of MHV-A59 Mpro. Further, the backbone carbonyl oxygen and NH of P3 form hydrogen bonds with the NH and backbone carbonyl oxygen of E166, respectively, which help fix the N3 inhibitor to MHV-A59 Mpro at the P3 location (Fig. 2b).

The side chain of the P4 position is a methyl group, which is suitably accommodated by the relatively shallow P4 pocket. The small inserted side chain forms hydrophobic interactions with A188 and Q192. Additionally, its backbone NH donates a weak hydrogen bond of 3.1 Å to the carbonyl oxygen of V190. The isoxazole of the P5 position is also partially solvent exposed and forms Van der Waals interactions with the backbone of residue V191 (Fig. 2b). In summary, P3, P4 and P5 of the inhibitor N3 interact with MHV-A59 Mpro in a similar pattern to other CoV Mpros.

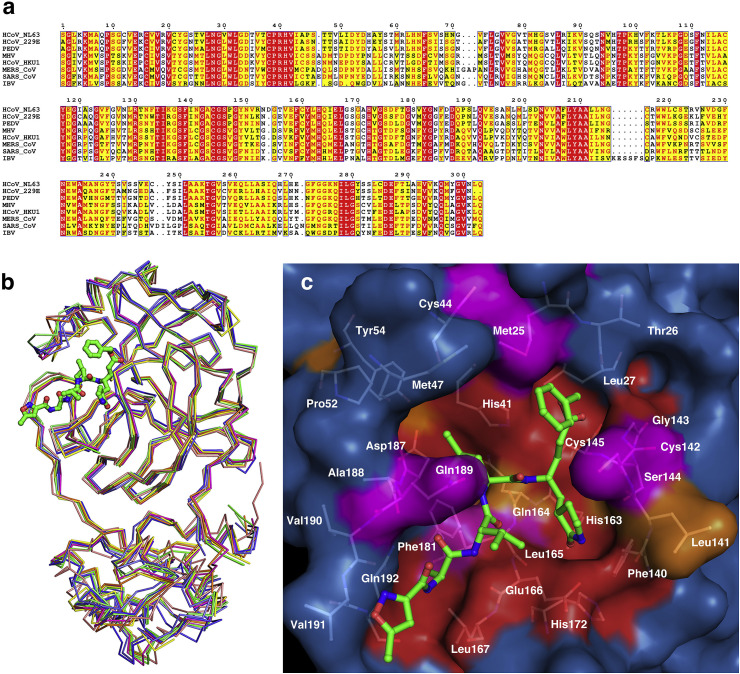

3.6. Structural conservation of Mpro among CoVs

As a pathogenic model, MHV-A59 is commonly used to explore the virus-host interaction of many CoVs. Then, we compared the Mpro structure of MHV-A59 with that from various CoVs, such as HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-HKU1, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, PEDV and IBV (Fig. 3 b). All these CoVs exhibit a similar shape of Mpro (RMSD is 0.9–1.9 Å), and the most distinct CoVs are PEDV (RMSD is 1.9 Å) and IBV (RMSD is 1.4 Å). Further comparisons show that domain I and domain II overlap well (RMSD is 0.8–1.1 Å), while domain III and the linking loop exhibit a slight shift of Cα. For domain III, IBV is the most different with an RMSD of 1.8 Å. Considering the similarity of the topological structure of domain I–III, the difference of PEDV Mpro is most likely caused by the reorientation of the connecting loop during crystallization packing. Moreover, the group-specific S2 lid also displayed diverse conformations. However, this structural diversity was reported to cause no group-specific substrate preferences. Above all, overall structure alignment demonstrates significant homology among these 7 CoVs.

Fig. 3.

Structural conservation analysis of Mproamong CoVs.

(a) Sequence alignment of Mpro from MHV-A59 and 7 various CoVs: HCoV-229E, HCoV-HKU1, HCoV-NL63, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, PEDV and IBV. (b) Superposition of Mpro from MHV-A59 and 7 various CoVs in complex with peptide substrate analogs (MHV-A59, green; HCoV-NL63, blue, PDB ID 5GWY; HCoV-HKU1, magenta, PDB ID 3D23; SARS-CoV, salmon, PDB ID 2AMQ; MERS-CoV, orange, PDB ID 5WKK; HCoV-229E, lime, PDB ID 2ZU2; PEDV, slate, PDB ID 5GWZ; IBV, yellow, PDB ID 2Q6F). (c) Surface representation of conserved substrate-binding pockets from various CoV Mpros. The background is MHV-A59 Mpro. Red: identical residues; orange: substitution in one CoV Mpro; magenta: substitution in two CoV Mpros; residues involved in N3 binding are shown as white sticks. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Then, we performed a closer inspection at the substrate-binding pocket bound with the inhibitor N3. The H41 and C145 of the catalytic dyad and F140 and H163, which maintain the oxyanion loop in the proper relative position, are completely conserved. For the binding pockets of P1—P5, the comprised residues are mostly conserved, especially for pockets S1, S2 and S4. The residues that directly interact with the N3 side chain or form the fundamental part of the pockets are completely identical, such as F140, H163, E166, and H172 of the S1 pocket; H41 and D187 of the S2 pocket; and L167 and Q192 of the S4 pocket. Residues that construct the outer wall or interact with the backbone of P3/P5, which bear solvent-exposed side chains, exhibit substitution with the same type of amino acid (Fig. 3c). Taken together, the results show that Michael acceptor suicide inhibitors such as N3 interact with MHV-A59 Mpro in a manner conserved among various CoVs.

In the last two decades, with global epidemics of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, CoVs have aroused widespread concern and a call for effective therapeutic and preventive strategies. Combination with animal infection models would facilitate the study of CoV pathogenesis and antiviral drug development. In our study, we first obtained a crystal of high quality for Mpro from MHV-A59, a prototype strain for animal infection models, and determined its 3D structure at high resolution after introducing a series of mutations to engineer its biophysical and chemical properties. In our structure, the pattern of interactions between MHV-A59 Mpro and N3 is generally similar to that between other CoV Mpros and N3. The C145 of the catalytic dyad forms an irreversible covalent bond with N3 and is stabilized by H41 and a loop from F140 to C145, which forms an oxyanion hole. Meanwhile, the lactam ring of the P1 side chain and the isobutyl group of the P2 side chain protrudes into the S1 and S2 pockets well, respectively. Both pockets are characterized by a preference for cleavage recognition sites: glutamine at P1 and leucine/methionine at P2. The residues constituting the whole binding pocket are largely conserved. Altogether, our findings will be helpful for the development of potent inhibitors carrying a Michael acceptor warhead or drugs for both existing and possibly emerging human CoVs.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at Beamline 17B, 18U and 19U of Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (China) for their assistance in data collection. This work was supported by the National Key Research Program of China (2016YFD0500300), the National Key Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) (2015CB859800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31528006), and the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars of TianJin (18JCJQJC48000).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.02.105.

Transparency document related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.02.105

Contributor Information

Zefang Wang, Email: zefangwang@tju.edu.cn.

Lei Zhang, Email: zhanglei@tju.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Transparency document

References

- 1.Masters P.S. Academic Press; 2006. The Molecular Biology of Coronaviruses, Advances in Virus Research; pp. 193–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss S.R., Navas-Martin S. Coronavirus pathogenesis and the emerging pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2005;69:635–664. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.4.635-664.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woo P.C.Y., Lau S.K.P., Lam C.S.F. Discovery of seven novel Mammalian and avian coronaviruses in the genus deltacoronavirus supports bat coronaviruses as the gene source of alphacoronavirus and betacoronavirus and avian coronaviruses as the gene source of gammacoronavirus and deltacoronavirus. J. Virol. 2012;86:3995–4008. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06540-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Z., Du J., Chen G. Coronavirus MHV-A59 infects the lung and causes severe pneumonia in C57BL/6 mice. Virol. Sin. 2014;29:393–402. doi: 10.1007/s12250-014-3530-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hervé L., Higgs M., Pawlotsky J.-M. Animal models in the study of hepatitis C virus-associated liver pathologies. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011;5:341–352. doi: 10.1586/egh.11.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye Y., Hauns K., Langland J.O. Mouse hepatitis coronavirus A59 nucleocapsid protein is a type I interferon antagonist. J. Virol. 2007;81:2554–2563. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01634-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang G., Chen G., Zheng D. PLP2 of mouse hepatitis virus A59 (MHV-A59) targets TBK1 to negatively regulate cellular type I interferon signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017192. e17192-e17192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lane T.E., Hosking M.P. The pathogenesis of murine coronavirus infection of the central nervous system. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2010;30:119–130. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v30.i2.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Day C.W., Baric R., Cai S.X. A new mouse-adapted strain of SARS-CoV as a lethal model for evaluating antiviral agents in vitro and in vivo. Virology. 2009;395:210–222. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang F., Chen C., Liu X. Crystal structure of feline infectious peritonitis virus main protease in complex with synergetic dual inhibitors. J. Virol. 2016;90:1910–1917. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02685-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xue X., Yu H., Yang H. Structures of two coronavirus main proteases: implications for substrate binding and antiviral drug design. J. Virol. 2008;82:2515–2527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02114-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haitao Y., Mark B., Zihe R. Drug design targeting the main protease, the achilles heel of coronaviruses. Curr. Pharmaceut. Des. 2006;12:4573–4590. doi: 10.2174/138161206779010369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H., Xue S., Yang H. Recent progress in the discovery of inhibitors targeting coronavirus proteases. Virol. Sin. 2016;31:24–30. doi: 10.1007/s12250-015-3711-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hilgenfeld R. From SARS to MERS: crystallographic studies on coronaviral proteases enable antiviral drug design. FEBS J. 2014;281:4085–4096. doi: 10.1111/febs.12936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paasche A., Zipper A., Schäfer S. Evidence for substrate binding-induced zwitterion formation in the catalytic cys-his dyad of the SARS-cov main protease. Biochemistry. 2014;53:5930–5946. doi: 10.1021/bi400604t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi J., Sivaraman J., Song J. Mechanism for controlling the dimer-monomer switch and coupling dimerization to catalysis of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 3C-like protease. J. Virol. 2008;82:4620–4629. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02680-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stobart C.C., Lee A.S., Lu X. Temperature-sensitive mutants and revertants in the coronavirus nonstructural protein 5 protease (3CLpro) define residues involved in long-distance communication and regulation of protease activity. J. Virol. 2012;86:4801–4810. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06754-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stobart C.C., Sexton N.R., Munjal H. Chimeric exchange of coronavirus nsp5 proteases (3CLpro) identifies common and divergent regulatory determinants of protease activity. J. Virol. 2013;87:12611–12618. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02050-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. [20] Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCoy A.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Adams P.D. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Afonine P.V., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Echols N. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2012;68:352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang H., Xie W., Xue X. Design of wide-spectrum inhibitors targeting coronavirus main proteases. PLoS Biol. 2005;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030324. e324-e324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.