Abstract

Ethnopharmacological relevance

In the pre-antibiotic era, a broad spectrum of medicinal plants was used to treat livestock. This knowledge was neglected in European veterinary medicine for decades but kept alive by farmers. Emergence of multidrug resistant bacterial strains requires a severely restricted use of antibiotics in veterinary medicine. We conducted a survey on the ethnoveterinary knowledge of farmers in the bilingual (French and German speaking) Western region of Switzerland, namely the cantons of Fribourg, Neuchâtel and Jura, and in the French speaking part of the canton of Bern.

Aim of the study

To find out whether differences exist in plants used by farmers in French speaking and bilingual regions of Switzerland as compared to our earlier studies conducted in Switzerland. Additional focus was on plants that are used in diseases which commonly are treated with antimicrobials, on plants used in skin afflictions, and on plants used in animal species such as horses, for which the range of veterinary medicinal products is limited.

Material and methods

We conducted in 2015 semistructured interviews with 62 dialog partners, mainly cattle keeping farmers but also 18 horse keeping farmers. Of these, 41 were native French (FNS) and 21 native German speakers (GNS). Detailed information about homemade herbal remedies (plant species, plant part, manufacturing process) and the corresponding use reports (target animal species, category of use, route of administration, dosage, source of knowledge, frequency of use, last time of use and farmers satisfaction) were collected.

Results

A total of 345 homemade remedies were reported, of which 240 contained only one plant species (Homemade Single Species Herbal Remedy Reports; HSHR). A total of 289 use reports (UR) were mentioned for the 240 HSHR, and they comprised 77 plant species belonging to 41 botanical families. Of these, 35 plant species were solely reported from FNS, 20 from GNS, and 22 from both. Taking into account earlier ethnoveterinary studies conducted in Switzerland only 10 (FNS) and 6 (GNS) plant species connected with 7% of FNS and GNS UR respectively were “unique” to the respective language group.

The majority of the UR (219) was for treatment of cattle, while 38 UR were intended to treat horses. The most UR were for treatment of gastrointestinal and skin diseases. The most frequently mentioned plants were Linum usitatissimum L., Coffea L., Matricaria chamomilla L., Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze, and Quercus robur L. for gastrointestinal diseases, and Calendula officinalis L., Hypericum perforatum L. and Sanicula europaea L. for skin afflictions.

Conclusion

No clear differences were found between the medicinal plants used by French native speakers and German native speakers. Several of the reported plants seem to be justified to widen the spectrum of veterinary therapeutic options in gastrointestinal and dermatological disorders in cattle and horses, and to reduce, at least to a certain degree, the need for antibiotic treatments. Our findings may help to strengthen the role of medicinal plants in veterinary research and practice, and to consider them as a further measure in official strategies for lowering the use of antibiotics.

Keywords: Ethnoveterinary medicine, French speaking swiss regions (Fribourg, Jura, Neuchâtel, Jura bernois), Medicinal plants, Antimicrobial, Livestock diseases

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; DP, dialog partners; dpe, dry plant equivalent; FNS, French native speaker; GNS, German native speaker; HSHR, Homemade-Single-Species Herbal Remedy Reports; MBW, Metabolic bodyweight; PSES, previous Swiss ethnoveterinary studies; QA, alimentary system and metabolism; QD, dermatologicals; QM, musculo-skeletal system; QG, genito urinary system and sex hormones; QG52, mastitis; QR, respiratory system; QS, sensory organs; UR, Use report; VAS, visual analog scale

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Ethnoveterinary research is defined as “systematic investigation and application of folk veterinary knowledge, theory and practice” (McCorkle, 1986). Therefore, it plays a major role in the conservation of traditional knowledge on medicinal plants, and in the exploration of alternative treatment options in veterinary medicine (Lans et al., 2007; Schäffer, 2010; Lans, 2016; Bullitta et al., 2018). European ethnoveterinary research has been performed mainly in Mediterranean countries (Blanco et al., 1999; Uncini Manganelli et al., 2001; Viegi et al., 2003; Scherrer et al., 2005; Pieroni et al., 2004, 2006; Bonet and Valles, 2007; Akerreta et al., 2010; Benitez et al., 2012; Mayer et al., 2014; Bullitta et al., 2018), in the German speaking parts of the European Alps (Schmid et al., 2012; Disler et al., 2014; Bischoff et al., 2016; Vogl et al., 2016; Mayer et al., 2017; Stucki et al., 2019), and some in eastern European countries (Mayer et al., 2014), notably Romania (Bartha et al., 2015). However, data from French speaking regions, such as western Switzerland, are lacking.

Uses of medicinal plants by farmers could differ not only by geographical territories but also between linguistic groups in a confined area. Such differences have been reported in human ethnomedicine (Menendez-Baceta et al., 2015), but similar comparisons with regard to veterinary use do not exist. Even if (a) earlier studies, comparing ethnoveterinary data from different countries (Viegi and Ghedira, 2014; Bartha et al., 2015; Mayer et al., 2017) suggest that “ethnoveterinary tradition may change with growing geographical distance” (Mayer et al., 2017) and, (b) a within-country comparison of two geographically and linguistically separate regions in Switzerland (Mayer et al., 2017), and a comparison of two populations within the same region of Romania (but without differentiating between different linguistic groups; Bartha et al., 2015) highlighted some differences in ethnoveterinary practises, a comparison of ethnoveterinary data of two linguistic populations within one region is still lacking.

In 2014 the WHO report on antimicrobial resistances (WHO, 2014) disclosed that resistance to antibiotics has meanwhile been detected in all parts of the world. There is evidence that farm animals act as a reservoir of resistance genes, and that transmission of such genes to humans could occur either via direct contact or via food consumption (WHO, 2004; Marshall and Levy, 2011). In addition, pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria carrying antimicrobial resistance gene are spread into the environment via the excrements of farm animals (Woolhouse et al., 2015).

Nonetheless, antimicrobials are still widely used to prevent or treat diseases in farm animals, but also for non-therapeutic purposes like growth promotion. On a global scale it is estimated that antimicrobials used in livestock production will increase by 67% from approximately 63′000 tons per year in 2010 to 106′000 tons by 2030 (Van Boeckel et al., 2015). The major classes of antimicrobials used for humans are also used in livestock, including reserve antibiotics (Aarestrup et al., 2008). In Europe the use of antimicrobials is highest with intensive livestock species such as pigs, poultry and young cattle (European Medicines Agency, 2014; Federal Food Savety and Veterinary Office, 2019), mainly for gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases (Bennett et al., 1999). In adult cattle mastitis is one of the most prevalent diseases (Bradley, 2002), and is oftentimes treated with antibiotics.

In Switzerland, the Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office (FSVO) reported the increase of microbiological resistance in zoonotic pathogens and in indicator bacteria (FSVO, 2019). A National Strategy on Antibiotic Resistance (StAR) has been developed to control and combat the development of antimicrobial resistance (StAR, 2015). However, even though the use of medicinal plants in prevention (Ayrle et al., 2019) or first line treatment of mild cases (Ayrle et al., 2016a) could possibly lower the need for antibiotic treatments of farm animals, it is not mentioned in StAR.

For indications such as topical treatment of skin afflictions, the number of available veterinary medicinal products in Switzerland is small. Only 18 veterinary drugs are registered for the treatment of dermatological disorders in livestock. The majority are either disinfecting agents or topical antibiotics (CPT, 2019). For some animal species the available veterinary medicinal products are even more limited. Over 100 antimicrobial drugs for systemic use in cattle are commercialized, but only 9 for use in horses (CPT, 2019).

There is a need to widen the spectrum of veterinary medicinal products and other therapeutic and preventive options for specific veterinary indications, and to reduce the use of antibiotics. However, even though the interest of veterinarians in herbal medicine has been increasing over the past decade (Kupper et al., 2018), there is still a lack of clinical veterinary research with medicinal plants (Ayrle et al., 2016a). In vitro and in vivo studies (Ayrle et al., 2016a), historical veterinary literature (Stucki et al., 2019) and ethnoveterinary surveys can serve as knowledge base for the veterinary use of medicinal plants.

With a survey conducted in the bilingual regions of the Cantons Fribourg, Jura, Neuchâtel, and the French speaking part of Bern (administration of Bernese Jura) we wanted.

-

(a)

to publish the first ethnoveterinary data from French speaking areas of Europe,

-

(b)

to compare the ethnoveterinary knowledge of native French and German speakers in the survey area, and

-

(c)

to evaluate whether medicinal plants discussed in this survey could be an option to enlarge the therapeutic spectrum with a particular emphasis on antimicrobial therapies, skin disorders, and horses.

2. Material and methods

The study was conducted according to previous ethnoveterinary studies from Switzerland (Schmid et al., 2012; Disler et al., 2014; Bischoff et al., 2016; Mayer et al., 2017; Stucki et al., 2019).

2.1. Study area

The survey was conducted in 3 western Swiss cantons, namely Fribourg, Neuchâtel, Jura, and in the French-speaking part of the canton of Bern, namely the administration of Bernese Jura (Fig. 1 ). The total study area is located between 6°3′ and 7°3′ E and 46°3′ and 47°3 N. The cantons Jura and Neuchâtel are bordered by France to the west, and the regions of previous Swiss ethnoveterinary studies (PSES, Fig. 1) to the east. The study covered an area of 3853.7 km2 and a population of approx. 600′000 persons. The majority of the population in the study area are native French speaking and, depending on the canton, up to one quarter are native German speaking persons (Bundesamt für Statistik, 2019). The altitude is between 373 and 2386m above sea level. Annual precipitation of the area varies from 947 mm to 1441 mm, and the average temperature at 647 m above sea level is 4.6 °C (Bundesamt für Meteorologie und Klimatologie, 2019). The area had a total of 5431 farms, of which 4365 kept cattle and 1361 kept horses (Bundesamt für Statistik, 2013).

Fig. 1.

Western Swiss French speaking and bilingual (French and German) regions (the research area of the recent project) and regions of former publications regarding Swiss ethnoveterinary data (Schmid et al., 2012; Disler et al., 2014; Bischoff et al., 2016; Mayer et al., 2017; Stucki et al., 2019).

2.2. Farms and dialog partners

Dialog partners (DP) were recruited according to a previously described approach (Disler et al., 2014). In a first step, the Departments of Agriculture of the cantons Fribourg, Jura and Neuchâtel supported the project by informing all farmers via bulletin or newsletters. Second, all organic farmers in the study area were informed via personal letter or e-mail. Additionally, farmers were informed through publications in the regional agricultural press. All farmers of the research area who were known to be member of complementary medicine working groups, or member of the farm research network of the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) were contacted by telephone. Furthermore, the project was presented at two general assemblies of regional associations of organic farmers (Bio Jura, Bio Fribourg, Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Recruitment of dialog partners for the study via snowball sampling. DP = dialog partner; FNS = French native speaker; GNS German native speaker). Informants are persons without own ethnoveterinary knowledge who acted as intermediaries in recruiting further DP.

A total of 62 dialog partners (DP) participated in the study: 26 DP (42%) in Fribourg, 15 (24%) in Jura, 11 (18%) in Bernese Jura, and 10 (16%) in Neuchâtel (Fig. 2). Thirty-one farmers spontaneously agreed (contacting the research team spontaneously based on the overall information via bulletin, newsletter, or individual letter or confirmed their participation during the telephone calls or personal meetings) to become a DP, while further 31 DP were recruited via snowball sampling (Bernhard, 2006; Disler et al., 2014, Fig. 2). DP who had spontaneously agreed to participate were asked whether they knew of other farmers using medicinal plants for their livestock. Additional DP were recruited with the help of farmers or farm advisors who by themselves were not using ethnoveterinary knowledge. For these intermediary persons the term “informant” was used (e.g. informant 1 established the contact to DP23; Fig. 2).

Thirteen DP were recruited from the complementary medicine working groups, 12 from the organic farm research network of the FiBL, and further 37 farmers were recruited via regional information (Fig. 2). The mother tongue of 41 DP was French (French Native Speakers, FNS), and German for the remaining 21 DP (German Native Speakers, GNS).

Each of the 62 DP was associated to a single farm, of which 25 (40%) were organic and 37 (60%) were non-organic. Forty-four farms kept cattle, 22 farms hen, 18 farms horses, 15 farms goats, 15 sheep, 6 rabbits, 5 pigs, 3 kept donkeys, 3 kept bees, and 1 kept deer. The farms were located between 430 and 1250 m (808m ± 194m) above sea level.

Thirty-two interviews were carried out with the DP only. In 27 cases, one or two family members, and in further 3 cases neighbours or farm staff were assisting the DP. All supplementary information from assisting persons were matched to the respective DP. In total, 93 persons aged between 28 and 87 years (54 ± 14) were interviewed. Of these 59 were men (63%) and 34 (37%) were women.

2.3. Data collection

Open, semi-structured interviews with DP were conducted from mid-February to end of April 2015 by the first author (DM) who is a native French speaker with an excellent command of German. The interviews were conducted in the mother tongue of the DP by using questionnaires in either French or German. In some interviews, language was occasionally switched if it helped to clarify specific points between DP and the interviewer. All information from one interview was assigned to the mother tongue of the DP.

The interviews took between 0.5 and 4.0 h and were recorded (WS-818 Digital Voice Recorder, Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) after a written consent of the DP.

With the aid of their local vernacular names, plants were identified during the interviews together with the DP, utilizing the Flora Helvetica (Lauber and Wagner, 2007), by cross-checking (a) illustrations and, (b) distribution areas of the plant species. If plant material was available, further cross-checking was done based on information and material collected in earlier studies (Disler et al., 2014; Mayer et al., 2017; Stucki et al., 2019). Commercial products and herbal drugs or extracts from commercial sources were identified with the aid of the package leaflet, or were considered as correctly delivered by the pharmacy or drug store. In the summer of 2015 nine dialog partners were revisited. A total of 27 herbarium voucher specimen of 16 plant species harvested from the wild were collected together with the dialog partner, dried, labelled, and deposited at the herbarium of the “Basler Botanische Gesellschaft”. All plants for which voucher specimens were available from this and from former Swiss studies (Disler et al., 2014; Mayer et al., 2017; Stucki et al., 2019) are listed in Additional File 1.

2.4. Definition of the applied ethnoveterinary units

The same definitions as in earlier studies were used (Disler et al., 2014; Bischoff et al., 2016; Mayer et al., 2017; Stucki et al., 2019).

Homemade remedy report (HR): [dialog partner] x [plant species or other natural product] x [plant part] x [manufacturing process of the finished product]

Use Report (UR): [homemade remedy report] x [category of use] x [specification of use] x [animal species] x [animal age classification] x [administration procedure]

The specification of use followed mainly the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system for veterinary medicinal products (ATCvet Code, WHO, 2018).

2.5. Determination of dosages

To estimate the dosing of plants, the weight of the amount of plant material used for a remedy was determined with a precision scale (EMB, 2000-2, Kern, Balingen, Germany). Whenever possible weight was determined using the original plant material of the farmer, or reference drugs of the interviewer on site. If this was not possible, the dosage was estimated by assessing the volume of plant material and measuring it subsequently by the interviewer. For orally administered remedies the oral daily dosage of medicinal plant (dry plant equivalent, dpe), and for externally administered remedies the concentration in g dpe per 100 g of final product was determined. Oral daily dosages were calculated in g dpe per kg metabolic bodyweight (kg0.75) (Löscher et al., 2014). The metabolic bodyweight was calculated with the average live weight of animal species and age classes described by Disler et al. (2014), or based on additional information (Sambraus, 1996, Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Metabolic bodyweight (according to Disler et al., 2014, and Sambraus, 1996).

| Species | Weight | Metabolic bodyweight (MBW) |

|---|---|---|

| Adult cattle | 650 kg | 128.7 kg0.75 |

| Adult horse | 650 kg | 128.7 kg0.75 |

| Calf | 75 kg | 25.5 kg0.75 |

| Adult sheep | 80 kg | 27. 0 kg0.75 |

| Young sheep | 20 kg | 9.5 kg0.75 |

| Rabbit | 3 kg | 2.3 kg0.75 |

| Hen | 1 kg | 1 kg0.75 |

| Human | 65 kg | 22.9 kg0.75 |

2.6. Satisfaction with the use reports (UR)

The degree of satisfaction of the DP with the reported use was determined using a visual analog scale of 100 mm, ranging from “no effect” (0 mm) to “very good effect” (100 mm) (Zealley, and Aitken, 1969).

3. Results

A total of 345 homemade remedy reports were recorded during the 62 interviews. Between 1 and 13 remedies (6 ± 3) per DP were reported, and they were associated with one to four different UR (1.2 ± 0.5). A total of 121 plants species from 41 botanical families were reported.

A total of 240 (70%) homemade remedies contained a single plant species (homemade single species herbal remedy reports, HSHR), and 31 (9%) homemade remedy reports were for mixtures with two to twenty-seven plant species. The remaining 74 (21%) were homemade remedy reports without use of plants, but contained natural products such as vinegar, wine, clay, honey, propolis or ashes.

3.1. Composition and manufacturing process for homemade single species herbal remedy reports (HSHR)

The 240 HSHR referred to 77 different plant species belonging to 41 botanical families. Species of the family Asteraceae were most frequently used (34 HSHR, 14%), followed by Linaceae (28 HSHR, 12%), Rubiaceae (20 HSHR, 8%), Apiaceae (19 HSHR, 8%), Theaceae (15 HSHR, 6%), and Berberidaceae (13 HSHR, 5%; Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Extraction procedure in the 240 homemade single species herbal remedy reports (HSHR).

| Botanical family (Number of named plant species in the family) | Plant species with ≥3 named HSHR (Number indicate the frequency of mentioned 239 HSHR) | On-farm extraction procedure (Number indicate the frequency of HSHR) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial products |

None | Water |

Alcohol |

Oil/Fat |

|||||

| Room temperature | Infusion | Decoction | Room temperature | Room temperature | Heated up | ||||

| Linaceae (1) | Linum usitatissimum L. (28) | ||||||||

| Semen (28) | 5 | 3 | 20 | ||||||

| Rubiaceae (1) | Coffea L. (20) | ||||||||

| Semen (20) | 20 | ||||||||

| Asteraceae (7) | All Asteraceae (34) | 2 | 3 | 20 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | |

| Matricaria chamomilla L. (16) | |||||||||

| Flos and flos sine calice (15) | 15 | ||||||||

| Herba (1) | 1 | ||||||||

| Calendula officinalis L. (10) | |||||||||

| Flos (8) | 1g | 1 | 2 | 4 | |||||

| Herba (2) | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Achillea millefolium L. (3) | |||||||||

| Herba (3) | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| Other Asteraceae (5)a | 1h | 1 | 3 | ||||||

| Theaceae (1) | Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze. (15) | ||||||||

| Folium (15) | 15 | ||||||||

| Berberidaceae (1) | Berberis vulgaris L. (13) | ||||||||

| Herba (13)l | 13 | ||||||||

| Apiaceae (5) | All Apiaceae (19) | 8 | 10 | 1 | |||||

| Sanicula europaea L. (13) | |||||||||

| Folium (12) | 2 | 9 | 1 | ||||||

| Flos (1) | 1 | ||||||||

| Other Apiaceae (6)b | 6 | ||||||||

| Fagaceae (1) | Quercus robur L. (9) | ||||||||

| Cortex (9) | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Boraginaceae (1) | Symphytum officinale L. (6) | ||||||||

| Radix (3) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Folium (2) | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| n.a | 1i | ||||||||

| Urticaceae (1) | Urtica dioica L. (6) | ||||||||

| Herba (6) | 5 | 1 | |||||||

| Hypericaceae (1) | Hypericum perforatum L. (4) | ||||||||

| Flos (3) | 3 | ||||||||

| Herba (1) | 1 | ||||||||

| Pinaceae (2) | All Pinaceae (7) | 5 | 2 | ||||||

| Abies alba MILL.(4) | |||||||||

| Herba (4) m | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Picea abies (L.) H. Karst. (3) | |||||||||

| Resina (2) | 2 | ||||||||

| Herba (1) n | 1* | ||||||||

| Aquifoliaceae (1) | Ilex aquifolium L. (4)l | 4 | |||||||

| Herba (4) | |||||||||

| Aspleniaceae (1) | Phyllitis scolopéndrium (L.) Newman (3) | ||||||||

| Folium (3) | 3 | ||||||||

| Malvaceae (2) | All Malvaceae (5) | 5 | |||||||

| Malva neglecta Wallr. (3) | |||||||||

| Folium (1) | 1 | ||||||||

| Herba (2) | 2 | ||||||||

| Other Malvaceae (2)c | 2 | ||||||||

| Lamiaceae (7) | All Lamiaceae (11) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Thymus vulgaris L. (4) | |||||||||

| Herba (4) | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Other Lamiaceae (7)d | 3j,k | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Rosaceae (6) | All Rosaceae (8) | 8 | |||||||

| Prunus spinosa L. (3) | |||||||||

| Herba (3) l | 3 | ||||||||

| Other Rosaceae (5)e | 5 | ||||||||

| Gentianaceae (1) | Gentiana lutea L. (3) | ||||||||

| Radix (3) | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| Othersf(37) | 37 other plant species (45) | 6 | 23 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Total (77) | Total (240) | 12 | 86 | 6 | 92 | 27 | 7 | 8 | 2 |

n.a. information not available.

Arnica montana L. (2), Matricaria discoidea DC.(2), Leontopodium nivale subsp. alpinum (Cass.) Greuter. (1), Bellis perennis L. (1).

Carum carvi L (2)., Daucus carota L.(2), Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss (1) Peucedanum ostruthium (L.) W.D.J.Koch (1).

Malva sylvestris L. (2).

Salvia officinalis L. (1), Mentha canadensis L. (1) Origanum vulgare L.(1), Mentha longifolia (L.) L. (1), Lavandula × intermedia Emeric ex Loisel. (1), Lavandula angustifolia Mill (2).

Alchemilla xanthochlora Rothm. (1), Rosa canina L. (1), Malus domestica Borkh.(1), Sorbus aucuparia L. (2), Rubus idaeus L. (1).

Allium cepa L.(2) (Liliaceae), Allium ursinum L. (1) (Liliaceae), Allium sativum L. (1) (Liliaceae), Aristolochia clematitis L. (1) (Aristolochiaceae); Atropa belladonna.L. (1) (Solanaceae), Beta vulgaris L. (subsp. vulgaris) (1) (Amaranthaceae), Brassica oleracea L. (convar. capitata var. sabauda L.) (1) (Brassicaceae), Chelidonium majus L. (1) (Papaveraceae), Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J.Presl (2) (Lauraceae), Cinnamomum verum J.Presl (1) (Lauraceae), Citrus x aurantium L.(1) (Rutaceae), Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck (2) (Rutaceae), Cucumis sativus L. (1) (Curcubitaceae), Equisetum arvense L. (2) (Equisetaceae), (Myrtaceae), Fagopyrum esculentum Moench (1) (Polygonaceae), Geranium robertianum L. (1) (Geraniaceae), Harpagophytum procumbens (Burch.) DC ex Meisn.(1), (Pedaliaceae), Hordeum vulgare L. (1) (Poaceae), Juglans regia L. (2) (Juglandaceae), Juniperus communis L. (2) (Cupressaceae), Melaleuca alternifolia (Maiden & Betche) Cheel (2) (Myrtaceae), Oryza sativa L. (2) (Poaceae), Plantago lanceolata L. (1) (Plantaginaceae), Plantago media L. (1) (Plantaginaceae), Polygonum aviculare L. (1) (Polygonaceae), Raphanus raphanistrum subsp. sativus (L.) Domin (1), (Brassicaceae), Rhamnus alpina L. (1) (Rhamnaceae), Rhamnus cathartica L. (1) (Rhamnaceae), Rumex conglomeratus Murray (1) (Polygonaceae), Rumex obtusifolius L. (1) (Polygonaceae), Sambucus nigra L. (1) (Caprifoliaceae), Sinapis alba L. (1) (Brassicaceae), Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & L.M.Perry (1) (Myrtaceae), Trigonella foenum-graecum L.(1) (Polygonaceae), Triticum aestivum L.(1) (Poaceae), Veratrum album L.(1) (Melanthiaceae), Zingiber officinale Roscoe (1) (Zingiberaceae).

Calendula ointment Sanicare (online pharmacy) Bombastus-Werke AG, used in one HSHR.

Arnica tincture (pharmacy) used in one HSHR.

Comfrey gel (drugstore) used in one HSHR.

Lavendula angustifolia oil (pharmacy) used in one HSHR; Lavendula x hybrid oil (internet: aroma-zone.com) with alcohol mixed, used in one use report.

NJP Liniment(R) Swissgenetics (containing Mentha arvenses L.) used in one HSHR.

Plant part: twigs.

Plant Part: buds in two remedy, twigs in 3 remedies.

Plant part: buds; * sugar extraction.

The most often reported plant species was Linum usitatissimum L. (28 HSHR; 12%), followed by Coffea L. (20 HSHR; 8%), Matricaria chamomilla L. (16 HSHR; 7%), Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze. (15 HSHR; 6%), and Sanicula europaea L. (13 HSHR; 5%). Eighteen plant species were reported for the first time for an ethnoveterinary use in Switzerland. Of these, ten were mentioned solely by FNS (Citrus x aurantium L., Fagopyrum esculentum Moench, Lavendula x intermedia Emeric ex Loisel, Matricaria discoidea DC., Polygonum aviculare L., Raphanus raphanistrum subsp. sativus (L.) Domin, Rumex conglomeratus Murray, Sinapis alba L., Sorbus aucuparia L., Zingiber officinale Roscoe), and six solely by GNS (Atropa belladonna L., Cucumis sativus L., Hordeum vulgare L., Mentha longifolia (L.) L., Triticum aestivum L., Veratrum album L.). Additional two species (Oryza sativa L., Phyllitis scolopendrium (L.) Newman) were reported by both FNS and GNS.

The most frequently used plant parts were herbs (61 HSHR, 25%) and seeds (59 HSHR, 24%), followed by leaves (45 HSHR, 19%), flowers (35 HSHR, 15%), bark (12 HSHR, 5%), roots (12 HSHR, 5%), and fruits (7 HSHR, 3%). The remaining 9 HSHR (4%) included bulbs, resins, or unknown plant parts.

For 112 HSHR (47%) the plant material was purchased, for 110 HSHR (46%) gathered from the wild, and for 18 HSHR (8%) cultivated on farm. Dried plant material was used in 154 HSHR (64%), fresh plants were used in 71 HSHR (30%), while for 15 HSHR (6%) no information was available.

In more than half of the HSRH (142, 60%; Table 2), the remedies were prepared using an extraction process on farm. In 86 HSRH (35%) the plants were directly administered without prior extraction. This was mainly for oral or topical administration. Twelve HSHR (5%) comprised commercial products, out of which seven were essentials oils (Table 2, Additional file 1).

For 125 HSHR an aqueous extraction was reported, either as infusion (92 HSRH), decoction (27 HSRH), or extraction at room temperature (6 HSRH). In 7 HSRH alcohol was used for extraction, and oil or fat in 10 HSRH. Sugar was used in one case to prepare a syrup from Picea abies (L.) H. Karst.

The weight of plant used to prepare the remedies could be determined for 173 HSHR (71%). In 78 cases the amount was directly measured on farm (in 26 cases with the original herbal drug, and in 52 cases with the reference drug of the interviewer). In 95 cases an approximate volume of plant was assessed, and the weight was determined afterwards by the interviewer. For 67 HSHR (29%) it was not possible to determine the amount of plant material used.

3.2. Use reports

A total of 289 use reports (UR) were collected for the 240 HSHR. Most of them were for cattle (219 UR, 76%), followed by 39 UR for horses (13%), and 31 UR (11%) for other animals, such as sheep, goats, hens and rabbits (Table 3 , Additional file 1). The majority of the UR were for treatment (225; 78%), while 64 UR (22%) were for prophylactic use, mainly for prevention of cattle ringworm (Berberis vulgaris L.), or in the peripartum period (Linum usitatissimum L., Achillea millefolium L.).

Table 3.

List of 289 use reports (UR) for 240 homemade herbal remedies reports containing a single herb (HSHR): route of administration, categories of use, and target animal species.

| Botanical family (Number of named plant species in the family) | Plant species with ≥3 named HSHR (Number indicate the frequency of use reports) | (Numbers indicate the frequency of use reports) |

Total different use reports | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Routs of administration |

Categories of use |

Target animal species |

||||||||||||||||

| External |

Internal |

Treatment of housing environment | QD | QA | QG | QG 52 | QM | QR | Othersg | Cattle | Horse | Othersh | ||||||

| I | A | OR | IH | IU | ||||||||||||||

| Lineaceae (1) | Linum usitatissimum L. (35) | |||||||||||||||||

| Semen (35) | 5 | 30 | 4 | 24 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 29 | 5 | 1 | 35 | |||||||

| Rubiaceae (1) | Coffea L. (28) | |||||||||||||||||

| Semen (28) | 28 | 21 | 1 | 6 | 26 | 1 | 1 | 28 | ||||||||||

| Asteraceae (11) | All Asteraceae (45) | 4 | 18 | 23 | 19 | 18 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 38 | 3 | 4 | 45 | ||||

| Matricaria chamomilla L. (19) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Flos (17) | 3 | 14 | 3 | 12 | 2 | 16 | 1 | 17 | ||||||||||

| Herba (2) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Calendula officinalis L. (16) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Flos and flos sine calice (11) | 1 | 10i | 11 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 11 | |||||||||||

| Herba (5) | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||||

| Achillea millefoliumL. (4) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Herba (4) | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||

| Others Asteraceae (6)a | 2j | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1j | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |||||||

| Theaceae (1) | Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze. (16) | |||||||||||||||||

| Folium (16) | 1 | 15 | 15 | 1 | 15 | 1 | 16 | |||||||||||

| Berberidaceae(1) | Berberis vulgaris L. (14) | |||||||||||||||||

| Herba (14)o | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | ||||||||||||||

| Apiaceae (4) | All Apiaceae (27) | 1 | 20 | 6 | 19 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 10 | 4 | 27 | |||||

| Sanicula europaea L. (21) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Folium (18) | 17 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 10 | 7 | 1 | 18 | ||||||||||

| Flos (3) | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| OthersApiaceae (6) b | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| Fagaceae (1) | Quercus robur L. (9) | |||||||||||||||||

| Cortex (9) | 8 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 9 | 9 | ||||||||||||

| Boraginaceae (1) | Symphytum officinale L. (6) | |||||||||||||||||

| Radix (3) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Folium (2) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||

| n.a | 1k | 1k | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Urticaceae (1) | Urtica dioica L. (6) | |||||||||||||||||

| Herba (6) | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 6 | ||||||||||

| Hypericaceae (1) | Hypericum perforatumL. (9) | |||||||||||||||||

| Flos (8) | 1 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | ||||||||||

| Herba (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Pinaceae (2) | All Pinaceae (9) | 1 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 9 | ||||||

| Abies alba MILL .(5) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Herba (5) p | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | ||||||||||

| Picea abies (L.) H. Karst. (4) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Herba (2) q | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Resina (2) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Aquifoliaceae (1) | Ilex aquifolium L. (4)o | |||||||||||||||||

| Herba (4) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| Aspleniaceae (1) | Phyllitis scolopéndrium (L.) Newman (3) | |||||||||||||||||

| Folium (3) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||||||

| Malvaceae (2) | All Malvaceae (6) | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 6 | |||||||||

| Malva neglecta Wallr. (4) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Folium (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Herba (3) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Others Malvaceae (2)c | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Lamiaceae (7) | All Lamiaceae (11) | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 11 | |||

| Thymus vulgarisL. (4) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Herba (4) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||

| Others speciesd (7) | 1m | 2l,n | 2 | 1 | 1m | 1 | 1 | 1n | 4l | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 | |||||

| Rosaceae (6) | All Rosaceae (9) | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 9 | |||||||

| Prunus spinosa L. (3) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Herba (3)o | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||||||

| Others Rosaceaee (6) | 6 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||||

| Gentianaceae (1) | Gentiana lutea L. (5) | |||||||||||||||||

| Radix (5) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | ||||||||||||||

| Others (37) | 37 other plant speciesf (47) | 4 | 12 | 25 | 1 | 5 | 15 | 11 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 34 | 9 | 4 | 47 | |

| Total (77) | Total (289) | 19 | 71 | 168 | 1 | 2 | 28 | 97 | 111 | 20 | 6 | 6 | 13 | 36 | 219 | 39 | 31 | 289 |

n.a. information not available.

I - intact skin; A - alterated or sore skin; OR - oral; IH - inhalation; IU – intravaginal/intrauterine; QD – dermatologicals; QA – alimentary tract and metabolism; QG – genito-urinary system and sex hormones; QG52 – mastitis; QM – musculo-skeletal system; QR – respiratory system (WHO, 2018).

Arnica montana L. (2), Matricaria discoidea DC. (2), Leontopodium nivale subsp. alpinum (Cass.) Greuter. (1), Bellis perennis L. (1).

Carum carvi L (2)., Daucus carota L.(2), Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss (1) Peucedanum ostruthium (L.) W.D.J. Koch (1).

Malva sylvestris L. (2).

Salvia officinalis L. (1), Mentha canadensis L. (1) Origanum vulgare L.(1), Mentha longifolia (L.) L. (1), Lavandula × intermedia Emeric ex Loisel. (1), Lavandula angustifolia Mill (2).

Alchemilla xanthochlora Rothm. (1), Rosa canina L. (1), Malus domestica Borkh.(1), Sorbus aucuparia L. (2), Rubus idaeus L. (1).

Allium cepa L.(2) (Liliaceae), Allium sativum L. (1) (Liliaceae), Aristolochia clematitis L. (1) (Aristolochiaceae); Atropa belladonna.L. (1) (Solanaceae), Beta vulgaris L. (subsp. vulgaris) (1) (Amaranthaceae), Brassica oleracea L. (convar. capitata var. sabauda L.) (1) (Brassicaceae), Chelidonium majus L. (1) (Papaveraceae), Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J.Presl (2) (Lauraceae), Cinnamomum verum J.Presl (1) (Lauraceae), Citrus x aurantium L.(1) (Rutaceae), Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck (2) (Rutaceae), Cucumis sativus L. (1) (Curcubitaceae), Equisetum arvense L. (2) (Equisetaceae), (Myrtaceae), Fagopyrum esculentum Moench (1) (Polygonaceae), Geranium robertianum L. (1) (Geraniaceae), Harpagophytum procumbens (Burch.) DC ex Meisn.(1), (Pedaliaceae), Hordeum vulgare L. (1) (Poaceae), Juglans regia L. (2) (Juglandaceae), Juniperus communis L. (2) (Cupressaceae), Melaleuca alternifolia (Maiden & Betche) Cheel (2) (Myrtaceae), Oryza sativa L. (2) (Poaceae), Plantago lanceolata L. (1) (Plantaginaceae), Plantago media L. (1) (Plantaginaceae), Polygonum aviculare L. (1) (Polygonaceae Raphanus raphanistrum subsp. sativus (L.) Domin (1) (Brassicaceae), Rhamnus alpina L. (1) (Rhamnaceae), Rhamnus cathartica L. (1) (Rhamnaceae), Rumex conglomeratus Murray (1) (Polygonaceae), Rumex obtusifolius L. (1) (Polygonaceae), Sambucus nigra L. (1) (Caprifoliaceae), Sinapis alba L. (1) (Brassicaceae), Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & L.M.Perry (1) (Myrtaceae), Trigonella foenum-graecum L.(1) (Polygonaceae), Triticum aestivum L.(1) (Poaceae), Veratrum album L.(1) (Melanthiaceae), Zingiber officinale Roscoe (1) (Zingiberaceae).

Parasites, general strengthening, behaviour, sensory organs, varia.

Sheep, goats, hens, rabbits.

Calendula ointment Sanicare (online pharmacy), Bombastus-Werke AG used in 1 remedy for 1 use report.

Arnica tincture (pharmacy) used in 1 remedy for 1 use report.

Comfrey gel (drugstore) used in 1 remedy for 1 use report.

Lavendula angustifolia oil (internet: aroma-zone.com) used in 2 remedies for 2 use report.

Lavendula x hybrid oil (internet: aroma-zone.com) with alcohol mixed, used in 1 remedy for 1 use report.

NJP Liniment(R) Swissgenetics (containing Mentha arvenses L. var. piperascens) used in 1 use report.

Plant part: twigs.

Plant Part: buds in two remedies, twigs in 3 remedies.

Plant part: buds.

3.2.1. Categories of use

Gastrointestinal disorders and metabolic dysfunctions (QA; 111 UR, 38%) were the most often mentioned indication, followed by skin alterations and sores (QD; 97 UR, 34%). Other indications included infertility and diseases of female genitals (QG; 20 UR, 7%), diseases of the respiratory tract (QR; 13 UR, 5%), mastitis (QG52; 6 UR, 2%), musculoskeletal system (QM; 6 UR, 2%), and others, such as general strengthening (36 UR, 12%).

The most frequently reported plants for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders and metabolic dysfunctions were Linum usitatissimum L. (35 UR), Coffea L. (22 UR), Matricaria chamomilla L. (19 UR), and Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze. (16 UR). For the treatment of skin alterations and sores Sanicula europaea L. (21 UR) was most often mentioned, followed by Calendula officinalis L. (16 UR). Phyllitis scolopendrium (L.) Newman (3 UR) was most often used in afflictions of the respiratory tract (Table 3).

3.2.2. Route of administration

Oral administration (168 UR, 58%) was most frequently used (Table 3), mainly for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders like diarrhoeas, colic, constipation or rumination problems. The plants were mainly administered as infusion or decoction. Topical administration was described for 90 UR (31%), mainly for the treatment of altered and sore skin (71 UR), for disinfection of open wounds, or for the promotion of wound healing. Farmers used these HSRH as washes, compresses, or by direct application onto the skin of ointments, oils, tinctures, or fresh plants. Administration on intact skin (19 UR) was mainly described for the treatment of swellings, inflammations of joints, or other subcutaneous afflictions. Treatment of housing environment was mentioned in 28 UR (10%). To prevent or treat cattle ringworm twigs of Berberis vulgaris L, Ilex aquifolium L., or Prunus spinosa L., hanged up in the stable. Finally, two UR were for intravaginal/intrauterine administration, and one UR with essential oil of lavender (Lavendula angustifolia Mill.) was used as an inhalant for calming nervous horses.

3.2.3. Comparison of linguistic populations

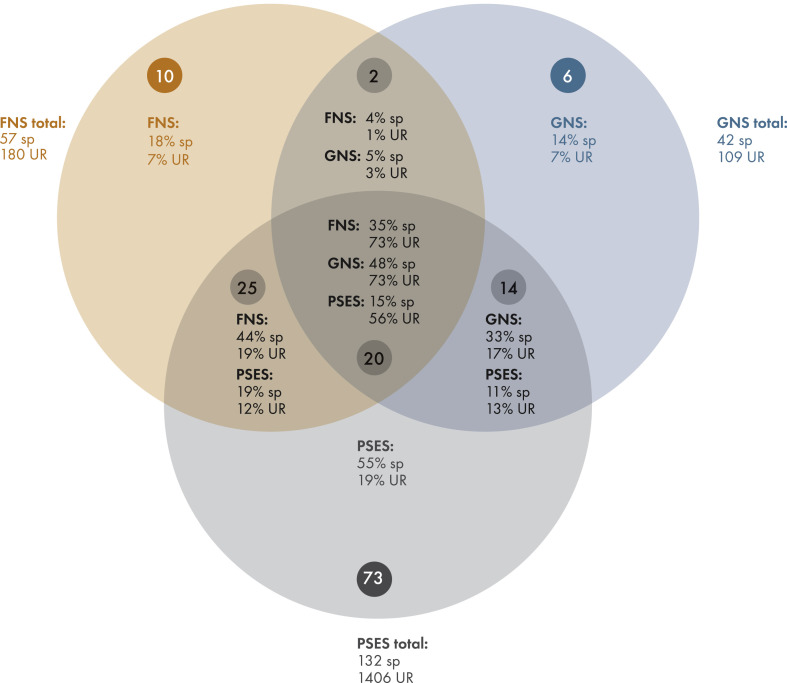

FNS reported a total of 57 plant species connected to 180 UR, and GNS described 42 plant species and 109 UR. Thirty-five plant species were solely reported from FNS, and 20 solely from GNS, and these species were associated with one quarter of the respective UR each. Twenty-two plant species were reported by both FNS and GNS, and were linked to three quarters of the respective UR. The degree of satisfaction of farmers with the treatments outcomes were evaluated for 247 UR, with an average value of 74 mm and no differences between the language groups (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Degree of satisfaction of users with the treatment outcomes measured on a Visual Analog Scale (VAS). Mean value and standard deviation of the VAS are represented. FNS = French native speakers; GNS = German native speakers; QA = Alimentary tract and metabolism; QD = Dermatological; QR = Respiratory tract; QG = Genito-urinary system.

4. Discussion

With a survey covering bilingual regions of Switzerland we here published the first ethnoveterinary data from French speaking areas of Europe. A total of 62 DP were interviewed, and 289 UR based on 240 HSHR were documented, comprising 77 different plant species from 41 botanical families. Compared to previous ethnoveterinary surveys (PSES; Schmid et al., 2012; Disler et al., 2014; Bischoff et al., 2016; Mayer et al., 2017; Stucki et al., 2019), 18 plant species were for the first time described for an ethnoveterinary use in Switzerland.

The methodology of the study was in accord with PSES. Most of the methodological recommendations for ethnopharmacological field studies were adhered to (Heinrich et al., 2018; Weckerle et al., 2018). The short duration of the survey (3 months in early spring) was due to the heavy workload of DP during the rest of the year (Stucki et al., 2019). Given that the survey had to be conducted outside of the vegetation period it was not possible to collect voucher specimen at the moment of the interviews. However, we collected some voucher specimen on some of the farms during the following summer (Additional file 1).

The cantons of Jura and Neuchâtel are officially French speaking, while Fribourg and Berne are officially bilingual (German and French). However, we considered only the French speaking Bernese Jura in our survey. Nevertheless, 41 DP were FNS, and 21 GNS. With one third of all DP, native German speakers appeared overrepresented if one considers the language distribution of the entire population of the study area (Bundesamt für Statistik, 2019). This may be due to the fact that German speaking Mennonites immigrating in the 18th century to the Jura region (cantons of Berne and Jura) were predominantly farmers (Gerber, 1969).

In general, farmers were satisfied with their treatment outcomes, and the mean value of 74 mm on the analog scale is comparable with values of PSES (70–80 mm).

4.1. Compliance and differences between the knowledge of French (FNS) and German native speakers (GNS)

We conducted the first comparative ethnoveterinary study with two populations of different mother tongues within the same geographic region of Europe. An earlier within-country comparison of two different linguistic regions of Switzerland (German and Italian) was characterized by topographical differences (lowland regions vs. southern mountain area; Mayer et al., 2017), while a study in Romania compared ethnoveterinary data from a Hungarian speaking minority in a region of Transilvania with data from Transsilvania that had been gathered earlier, but without differentiation of the mother tongue of DP (Bartha et al., 2015). To our knowledge, the only other study comparing traditional uses of two linguistic groups within the same geographic area was an ethnomedicinal survey conducted recently in north-eastern Spain (Menendec-Bacetta et al., 2015).

When comparing the data from the present study with findings from PSES (Fig. 4 , Additional file 2), no difference between GNS (19% of the reported plant species are new for ethnoveterinary use in Switzerland) and FNS (22% of the reported plant species are new for ethnoveterinary use in Switzerland) was found. Furthermore, only 8% (FNS) and 10% (GNS) of the respective UR were connected to the 18 newly reported plant species, whereas three quarters of plant species connected to nine tenths of the UR were in accord with PSES, without a difference between FNS and GNS. Here were also no differences between FNS and GNS regarding the degree of satisfaction with their UR (Fig. 3).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the number of different plant species (sp) and associated use reports (UR). FNS = French native speakers, GNS = German native speakers, PSES = previous Swiss ethnoveterinary studies (Schmid et al., 2012; Disler et al., 2014; Bischoff et al., 2016; Mayer et al., 2017; Stucki et al., 2019). All plant species are given in Additional file 2.

On first sight our findings are in contrast to Menendez-Bacetta et al. (2015) who found clear differences between Basque and Spanish speaking populations within the same geographic area. However, these differences were associated with political and cultural separatism. If separatist tendencies are missing as in our study area (Fig. 2), different mother tongues of DP alone did not lead to significant differences in ethnoveterinary traditions.

4.2. Extending the spectrum of veterinary therapeutic options

There is increased interest of veterinarians in herbal medicine (Walkenhorst, 2017; Stucki et al., 2019), and an undeniable need for possible therapeutic alternatives, in particular to reduce the use of antibiotics. Ethnoveterinary research may be an important source of knowledge on promising plant species and on dosage of administered remedies. As in earlier studies, we determined the quantity of administered plant material and compared with the dosage documented in PSES or in literature (Reichling et al., 2016; Wichtl, 2009; ESCOP, 2003; ESCOP, 2009, Table 4, Table 5 ). We calculated oral daily doses for seven medicinal plants, including the first ethnoveterinary based dosage for Gentiana lutea L. (median 0.26g/kg0.75). Our calculations were based on information from at least three UR (Table 3). The medians of the determined dosages per kg metabolic body weight (kg0.75) were similar to PSES, and to human and veterinary literature. However, as in PSES minimum and maximum values often differed by one to two orders of magnitude. Despite such big dosage ranges, placebo controlled studies in animals showed positive outcomes in the treatment groups, as was the case in studies with coneflower and garlic (Ayrle et al., 2016b, 2017). We calculated concentrations of five medicinal plants in finished products for external use, and the first dosage for Linum usitatissimum L. (median 6.25g/100g finished product). Again, the medians were similar to PSES, albeit slightly lower than recommended in human and veterinary literature (Table 5).

Table 4.

Daily dosage in dry plant equivalent per kg metabolic body weight (g/kg0.75) with homemade single species herbal remedy reports (HSHR) for orally administered use reports (UR).

| Plant species with ≥3 named HSHR and documented dosage | Daily dosage [g/kg0.75] |

Determined median daily dosage [g/kg0.75] (Stucki; Mayer (it); Mayer (de); Bischoff; Disler; Schmid) | Converted animal daily dose [g/kg0.75] (Reichling et al., 2016) | Converted human daily dose [g/kg0.75] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calf (75 kg) |

Cattle (650 kg) |

Horse (650 kg) |

Othersa | Arithmetic mean (median; minimum value-maximum value) | ||||

| (MWB = 25.5 g/kg0.75) | (MWB = 128.7 g/kg0.75) | (MWB = 128.7 g/kg0.75) | ||||||

| Linum usitatissimum L. | ||||||||

| Semen (29) | 39.22, 6.28, 1.57, 2.09, 9.80 | 0.43, 0.97, 0.97, 0.97, 0.78, 0.97, 0.70, 0.83, 0.65, 11.66, 2.05, 0.62, 0.33, 0.24, 1.55, 1.94, 0.77,1.24, 2.80, 0.80, 0.88, 0.88 | 0.971, 0.194 | 3.21 (0.97; 0.19–39.22) | 1.16; 5.79; -; 6.89; 5.16; 2.92 | 0.39-0.77 (cattle, horse), 1.06–2.66 (goat) | 0.66b (obstipation), 0.22-0.44b (gastritis/enteriti) | |

| Coffea L. | ||||||||

| Semen (27) | 1.01, 2.05,1.49 | 0.34, 0.62, 1.02, 0.59, 0.68, 0.42, 0.42, 0.37, 0.45, 0.45, 0.45, 2.03, 1.17, 1.17, 0.55, 0.28, 3.89, 1.94, 0.59, 0.39, 0.34, 0.51 | 0.09 | 1.78 | 0.93 (0.59; 0.09–3.89) | 0.35; 1.67; 1.19; 0.34; 0.35; 0.37 | ||

| Matricaria chamomilla L. | ||||||||

| Flos (14) | 0.56, 0.09, 0.43, 0.16, 0.19, 0.08, 0.12, 0.17, 1.18, 0,19, 0.55 | 0.02, 0.06 | 0..22 | 0.29 (0.18; 0.02–1.18) | 0.26; 0.63; 0.27; 0.35; 1.12; 0.22 | 0.19-0.39 (cattle), 0.27–0.53 (goat) | 0.39-0.52b | |

| Achillea millefolium L. | 0.22-0.44c | |||||||

| Herba (4) | 0.16 | 0.03, 0.22, 0.31 | 0.18 (0.19; 0.03–0.31) | -; 0.13; -; -; -; - | ||||

| Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze. | ||||||||

| Folium (15) | 0.70, 1.27, 0.27, 0.35, 0.80, 1.33, 0.51, 0.21, 0.22, 0.28, 0.64, 0.28, 1.41, 0.85 | 0.60 | 0.65 (0.60; 0.21–1.41) | 0.29; -; 0.38; 0.45; 0.64; - | 0.39-0.62 (cattle), 0.20–0.31 (calf) | 0.22-0.33c | ||

| Quercus robur L. | ||||||||

| Cortex (7) | 0.78, 1.45, 0.08, 6.42, 1.33 | 0.12, 0.02 | 1.43 (0.78; 0.02–6,42) | 0.47; -; 1.17; 0.87; -; - | 0.19-0.39 (cattle), 0.27–0.53 (goat) | 0.13c | ||

| Gentiana lutea L. | ||||||||

| Radix (5) | 0.59, 0.26 | 0.44, 0.23, 0.01 | 0,31 (0.26; 0.01–0.59) | -; -; -; -; -; - | 0.08-0.39 (cattle) | |||

Sheeps.

ESCOP monographs (ESCOP, 2003).

Wichtl, Teedrogen und Phytopharmaka, Ein Handbuch für die Praxis auf wissenschaftlicher Grundlage (Wichtl, 2009).

Table 5.

Concentration of medicinal plants for homemade single species herbal remedy reports (HSHR) in preparations for topical use.

| Plant species with ≥3 named HSHR and documented dosage | g dry plant equivalent in 100g finished product |

Median concentration other parts of Switzerland (Stucki; Mayer it; Mayer de; Bischoff; Disler) | Recommended concentration g dry plant equivalent in 100g finished product (ESCOP, 2003) |

Recommended concentration g dry plant equivalent in 100g finished product (Reichling) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction with water | Extration with alcohol | Extraction with oil/fat | Arithmetic mean (median; minimum value-maximum value) | Extraction with water | Extration with alcohol | Extraction with oil/fat | |||

| Linum usitatissimum L. | |||||||||

| semen (5) | 6.25, 6.25,12.01, 4.81, 4.81 | 6.83 (6.25; 4.81–12.01) | -; -; -; -; - | ||||||

| Matricaria chamomilla L. | |||||||||

| Flos (3) | 0.17, 0.17, 0.50 | 0.28 (0.17; 0.17–0.50) | 0.53; 0.50; 0.50; 0.38; 0.40 | 0.50 | 10.00 | ||||

| Calendula officinalis L. | |||||||||

| Flos and flos sine calice (6) | 2.27, 2.27, 2.27 | 0.70, 1.16, 4.81 | 1.42; 2.00; 0.83; 1.32; 0.91 | 0.67-1.33 | 20.00a | 1.00–5.00 | 11.11 | ||

| Herba (4 | 2.41, 2.41, 2.41, | 90.09 | |||||||

| Sanicula europaea L. | |||||||||

| Folium (14) | 0.67, 0.09, 0.10, 0.33, 0.40, 0.40, 0.97, 0.60, 0.60, 0.20, 0.40, 0.97 | 3.00, 3.00 | 0.84 (0.50; 0.09–3.00) | -; 0.13;- | |||||

| Flos (3) | 0.42, 0.42, 0.42 | ||||||||

| Hypericum perforatum L. | |||||||||

| Flos (7) | 0.51, 7.28, 2.66, 2.66, 2.66, 2.66, 2.66 | 3.02 (2.66; 0.51–7.28) | 1.56; 2.50; -; -; 1.69 | 5.00–10.00 | 5.00 | 5.00–10.00 | |||

40% ethanol.

Corresponding with the outcomes of PSES and former European ethnoveterinary data (Mayer et al., 2014) the categories QA and QD were the most often mentioned indications with 72% of all UR.

4.2.1. Plants in diseases for which antimicrobial treatments are often used

In Europe, antimicrobials are most widely used to treat gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases of pigs, poultry, and for fattening cattle, in particular calves (European Medicines Agency, 2014; Schnyder et al., 2019). Mastitis and endometritis are major problems in dairy cattle (Cabaret, 2003; Hovi et al., 2003), and the most important reasons for the use of antibiotics in these animals (Oliver et al., 2011). Consequently, the UR related to the QA, QR and QG (and in particular QG52; WHO, 2018) categories are of particular interest for possibly lowering the use of antibiotics. However, only a few UR were related to QG (26 UR) and QR (13 UR), and no single plant species stood out in terms of importance (Table 3). For the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders (QA) black tea, coffee, chamomile, linseed and oak bark were the most frequently used herbal drugs.

4.2.1.1. Black tea (Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze, Theae nigrae folium)

Farmers used infusions of black tea mainly to treat diarrhoea in calves. Black tea reportedly showed activity against bovine coronavirus and rotavirus (Friedman, 2007) which are among the main causes for diarrhoea and gastroenteritis in calves and cattle. Besides, antidiarrheal properties of black tea has been demonstrated in rodents (Besra et al., 2003; Hiller and Melzig, 2010). The additional CNS stimulant properties of black tea (Einother and Martens, 2013) might be beneficial for lethargic calves. The antibacterial, antiadhesive, antidiarrheal and spasmolytic properties of black tea may be beneficial in gastrointestinal diseases.

4.2.1.2. Coffee (Coffea L.,Coffeae semen)

As in PSES coffee was widely used, mainly to treat gastrointestinal disorders (QA) like constipation, colic, or rumination problems. Purine alkaloids reduce mental and physical fatigue, and chlorogenic acid stimulates gastric secretion (Hiller and Melzig, 2010). There is some previous evidence that coffee may be helpful to treat and prevent polyfactorial infectious diseases in calves (Ponepal et al., 1996).

4.2.1.3. Chamomile flowers (Matricaria chamomilla L., Matricariae flos)

Preparations with chamomile were used as an infusion mainly to treat diarrhoea in calves. Chamomile flavonoids showed spasmolytic effects on bovine intestinal smooth muscles (Mendel et al., 2016). Chamomile also exhibited in vitro antibacterial properties against pathogens relevant in gastrointestinal disorders of youngstock (Ayrle et al., 2016a). In vivo studies also show protective effects in gastric ulcera in mouse and rats (ESCOP, 2003; Cemek et al., 2010), and antidiarrheal properties in rats (Sebai et al., 2014).

4.2.1.4. Linseeds (Linum usitatissimum L., Lini semen)

A decoction of whole linseeds was orally administered to treat diarrhoea in calves. Farmers also used linseed to treat constipation and ruminating troubles, and a poultice was administered in ruminitis. Anti-inflammatory, antidiarrheal, and spasmolytic properties of linseeds are well known (ESCOP, 2003; Ayrle et al., 2016a), and linked to the content in mucilaginous polysaccharides. Linseeds are recommended to treat gastric inflammation and obstipation (ESCOP, 2003; Reichling et al., 2016).

4.2.1.5. Oak bark (Quercus robur L., Quercus cortex)

Farmers treated diarrhoea in calves with infusions or decoctions of oak bark, or fed oak bark powder directly. The high content in tannins is responsible for the antidiarrheal properties (Reichling et al., 2008). Oak bark extracts furthermore possess antibacterial and anti-quorum sensing activities (Deryabin and Tolmacheva, 2015).

4.2.2. Plants used in skin diseases

Marigold (Calendula officinalis L.), St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum L.) and wood sanicle (Sanicula europaea L.) were the most frequently used plants for the treatment of skin disorders. While the therapeutic potential of marigold and St. John’s Wort in veterinary medicine is recognized (Tresch et al., 2019), wood sanicle is poorly studied and merits further investigation.

Wood sanicle (Sanicula europaea L., Saniculae folium et flos).

Wood sanicle was already reported in PSES, but only with few UR. However, in an earlier ethnobotanical study on human use of medicinal plants in the canton of Jura, wood sanicle was one of the most often reported species. Use of wood sanicle thus appears to be a distinct particularity of the study area (Broquet, 2006). In the present survey, farmers used infusions of leaves or flowers to treat wounds or scars. Washing the injured skin or a direct application on the skin with a bandage were mentioned. Wood sanicle contains saponins as major phytochemicals, and is has also been used in human folk medicine (Hiller and Melzig, 2010). Anti-inflammatory activity of wood sanicle has been reported (Jacker and Hiller, 1976; Vogl et al., 2013).

4.2.3. Plants used in equine diseases

Compared to PSES, UR related to horses as target species were much higher in the present survey area (39 UR, 13%). This was likely due to the importance of horse breeding in this region (about 1400 farms kept horses). Apart from a study from the canton of Berne (Ryhner et al., 2018) referring to 27 plant species, recent European ethnoveterinary data in horses are scarce (Mayer et al., 2014).

In category QA, Coffea L. and Linum usitatissimum L. were documented for the same indication as for cattle. In category QD, farmers used Sanicula europaea L. (7 UR), Calendula officinalis L., and Hypericum perforatum L.. In category QM, Arnica montana L., Harpagophytum procumbens (Burch.) DC ex Meisn., Equisetum arvense L., and Zingiber officinale Roscoe were used to treat sprains and degenerative joint diseases. In category QR, Phyllitis scolopéndrium (L.) Newman was used to treat cough, whereby the dried plant was directly administered orally. In vitro antimicrobial activity of Phyllitis scolopéndrium (L.) Newman against pathogenic bacteria has been reported (Ferrazzano et al., 2013). Additional plants species mentioned in category QR were Abies alba Mill. and Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck.

Lavandula angustifolia Mill. was administered to calm nervous horses. Interestingly, this traditional use was recently corroborated in a clinical study with foals (Poutaraud et al., 2018).

4.2.4. General aspects

The plants most frequently reported by farmers in our current survey are inexpensive, easily available, and well known for human and veterinary medicinal purpose (Leonti and Verpoorte, 2017; Stucki et al., 2019). The phytochemistry, pharmacological properties, and therapeutic effectiveness is documented with numerous research publications and reviews (Ayrle et al., 2016a; Tresch et al., 2019). The use of complementary medicine and homemade remedies by farmers may help to lower the use of antibiotics (Maeschli et al., 2019). However, medicinal plants cannot replace antibiotics and other modern veterinary medicinal products, not the least for reasons of animal welfare. Nevertheless, a meaningful use of medicinal plants by veterinarians may limit the use of antibiotics and other modern veterinary medicinal products to particularly severe diseases. More clinical veterinary studies with medicinal plants are needed, and veterinary education as well as national strategies to control and combat the development of microbial resistance should take into account the use of medicinal plants as a means to reduce the use of antibiotics (StAR, 2015).

5. Conclusion

Farmers of mainly French speaking regions of Switzerland reported a total of 77 medicinal plants to treat and prevent livestock diseases. Of these, 18 were mentioned for the first time in a Swiss ethnoveterinary context. We found no obvious difference in ethnoveterinary knowledge between French and German native speakers. The most widely used plants are easily available and well known for human and veterinary purposes. Taking into account the current phytochemical knowledge, and in vitro and in vivo studies, several plants reported by farmers could be considered as promising treatment options for gastrointestinal and dermatological disorders in cattle and horses. The use of such plants and finished products could help to reduce, at least to a certain degree, the use of antibiotics. Thus, our findings may contribute to international strategies for limiting the use of antibiotics.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Doréane Mertenat: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Maja Dal Cero: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Christan R. Vogl: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Silvia Ivemeyer: Software, Writing - review & editing. Beat Meier: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Ariane Maeschli: Software, Writing - review & editing. Matthias Hamburger: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Michael Walkenhorst: Writing - original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all dialog partners for sharing their knowledge, the organic farms associations Bio Jura, Bio Fribourg and Bio Neuchatel, and the Departments of Agriculture of the cantons Fribourg, Jura and Neuchâtel for the good cooperation. The organic farmers associations “Bärner Bio Bure”, “Bio Appenzellerland”, “Bio Fürstentum Lichtenstein”, “Bio Ostschweiz”, “Bioverein Glarus”, the foundation Schaette, the foundation Sampo, the foundation Dreiklang, the foundation Freie Gemeinschaftsbank Basel, the SaluVet GmBH, the cantonal offices for agriculture and the cantonal organic advisory services of the cantons Aargau, Basel-Landschaft, Bern, Glarus, Luzern, Nidwalden, Schwyz, Solothurn, St. Gallen, Zürich and Zug, the Swiss Medical Society for Phytotherapy (Schweizerische Medizinische Gesellschaft für Phytotherpie, SMGP), the Swiss Veterinary Society for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (Schweizerische Tierärztliche Vereinigung für Komplementär-und Alternativmedizin, camvet.ch) and to the foundation Sur-la-Croix are acknowledged for the financial support. We thank Kurt Riedi for designing the figures, Osama Emam for preparing Fig. 4 and Additional file 1, and Sylvie Dartois for collecting, processing and labelling the voucher specimen.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2019.112184.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- Aarestrup F.M., Wegener H.C., Collignon P. Resistance in bacteria of the food chain: epidemiology and control strategies. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2008;6:733–750. doi: 10.1586/14787210.6.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerreta S., Calvo M., Cavero R. Ethnoveterinary knowledge in navarra (Iberian Peninsula) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;130:369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayrle H., Mevissen M., Kaske M., Nathues H., Grützner N., Melzig M., Walkenhorst M. Medicinal plants – prophylactic and therapeutic options for gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases in calves and piglets? A systematic review. BMC Vet. Res. 2016;12:89. doi: 10.1186/s12917-016-0714-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayrle H., Mevissen M., Melzig M., Kaske M., Walkenhorst M. Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench for prophylaxis of respiratory diseases in calves – how to find the right dosage. Planta Med. 2016;81(S 01) doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1596985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayrle H., Mevissen M., Nathues H., Walkenhorst M. Allium sativum L. for prophylaxis of diarrhea in weaned piglets - how to find the right dosage? Planta Med. Int. Open. 2017;4(S01) doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1608298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayrle H., Nathues H., Bieber A., Durrer M., Quander N., Mevissen M., Walkenhorst M. Placebo-controlled study on the effects of oral administration of Allium sativum L. in postweaning piglets. Vet. Rec. 2019 doi: 10.1136/vr.10513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartha S.G., Quave C.L., Balogh L., Papp N. Ethnoveterinary practices of covasna county, transylvania, Romania. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015;11:35. doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0020-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitez G., Gonzalez-Tejero M., Molero-Mesa J. Knowledge of ethnoveterinary medicine in the province of granada, andalusia, Spain. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012;139:429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett R.M., Christiansen K., Clifton-Hadley R.S. Direct costs of endemic diseases of farm animals in Great Britain. Vet. Rec. 1999;145:376–377. doi: 10.1136/vr.145.13.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard H.R. Altamira Press; Walnut Creek, USA: 2006. Research Methods in Anthropology - Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. [Google Scholar]

- Besra S., Gomes A., Ganguly D., Vedasiromoni J. Antidiarrhoeal activity of hot water extract of black tea (Camellia sinensis) Phytother Res. 2003;17:380–384. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff T., Vogl C.R., Ivemeyer S., Klarer F., Meier B., Hamburger M., Walkenhorst M. Plant and natural product based homemade remedies manufactured and used by farmers of six central Swiss cantons to treat livestock. Livest. Sci. 2016;189:110–125. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco E., Macia M., Morales R. Medicinal and veterinary plants of el caurel (galicia, northwest Spain) J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999;65:113–124. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonet M., Valles J. Ethnobotany of Montseny biosphere reserve (Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula): plants used in veterinary medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;110:130–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley A. Bovine mastitis: an evolving disease. Vet. J. 2002;164:116–128. doi: 10.1053/tvjl.2002.0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broquet C. Master‐Thesis Université Neuchâtel; Switzerland: 2006. Chasseral, à la rencontre de l’homme et du végétal; Enquêtes ethnobotaniques sur l’utilisation des plantes dans une région de la chaîne Jurassienne. [Google Scholar]

- Bullitta S., Re G.A., Manunta M.D.I., Piluzza G. Traditional knowledge about plant, animal, and mineral-based remedies to treat cattle, pigs, horses, and other domestic animals in the Mediterranean island of Sardinia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018;14:50. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0250-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundesamt für Meteorologie und Klimatologie MeteoSchweiz 2019. https://www.meteoschweiz.admin.ch/home/klima/schweizer-klima-im-detail/monats-und-jahresgitterkarten.html last visit 18.03.2019.

- Bundesamt für Statistik . 2013. Landwirtschaftsstatistik.http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/regionen/regionalportraets.html (last visit 18.03.2019); Available from: [Google Scholar]

- Bundesamt für Statistik . 2019. Sprachen.https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/bevoelkerung/sprachen-religionen/sprachen.assetdetail.7226714.html (last visit 16.04.2019) [Google Scholar]

- Cabaret J. Animal health problems in organic farming: subjective and objective assessments and farmers' actions. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2003;80:99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Cemek M., Yilmaz E., Buyukokuroglu M. Protective effect of Matricaria chamomilla on ethanol-induced acute gastric mucosal injury in rats. Pharm. Biol. 2010;48:757–763. doi: 10.3109/13880200903296147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CPT, CliniPharm/CliniTox . 2019. Tierarzneimittel Kompendium der Schweiz.https://www.vetpharm.uzh.ch/perldocs/index_i.htm last visit 29.05.2019. [Google Scholar]

- Deryabin D.G., Tolmacheva A.A. Antibacterial and anti-quorum sensing molecular composition derived from Quercus cortex (Oak bark) extract. Molecules. 2015;20:17093–17108. doi: 10.3390/molecules200917093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disler M., Ivemeyer S., Hamburger M., Vogl C., Tesic A., Klarer F., Meier B., Walkenhorst M. Ethnoveterinary herbal remedies used by farmers in four north-eastern Swiss cantons (St. Gallen, Thurgau, Appenzell Innerrhoden and Appenzell Ausserrhoden) J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014;10:32. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einother S.J., Martens V.E. Acute effects of tea consumption on attention and mood. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013;98:1700S–1708S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.058248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESCOP Monographs . Georg Thieme Verlag; Stuttgart: 2003. The Scientific Foundation for Herbal Medicinal Products, Second Edition, Supplement 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ESCOP Monographs . second ed. Georg Thieme Verlag; Stuttgart: 2009. The Scientific Foundation for Herbal Medicinal Products. [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency E. Sales of veterinary antimicrobial agents in 26 EU/EEA countries in 2012. 2014. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2014/10/WC500175671.pdf

- Ferrazzano G.F., Roberto L., Catania M.R., Chiaviello A., De Natale A., Roscetto E., Pinto G., Pollio A., Ingenito A., Palumbo G. Screening and scoring of antimicrobial and biological activities of Italian vulnerary plants against major oral pathogenic bacteria. Evid. Based Complement Altern. Med. 2013:316280. doi: 10.1155/2013/316280. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M. Overview of antibacterial, antitoxin, antiviral, and antifungal activities of tea flavonoids and teas. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007;51:116–134. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200600173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FSVO (Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office) 2019. Statistics and Reports. Swiss Antibiotic Resistance Report 2018.www.blv.admin.ch/blv/en/home/tiere/publikationen-und-forschung/statistiken-berichte-tiere.html last visit 29.05.2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber A. Die Deutschschweizer im Berner Jura. Bern. Z. Gesch. Heimatkd. 1969;31:75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich M., Lardos A., Leonti M., Weckerle C., Willcox M., with the ConSEFS advisory group Best practice in research: consensus statement on ethnopharmacological field studies - ConSEFS. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018;211:329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller K., Melzig M.F. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag; Heidelberg: 2010. Lexikon der Arneipflanzen und Drogen. [Google Scholar]

- Hovi M., Sundrum A., Thamsborg S.M. Animal health and welfare in organic livestock production in Europe: current state and future challenges. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2003;80:41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jacker H.J., Hiller K. The antiexudative effect of saponin 5 from Eryngium planum L. and Sanicula europaea L. Die Pharmazie. 1976;31:747–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupper J., Walkenhorst M., Ayrle H., Mevissen M., Demuth D., Naegeli H. Online-Informationssystem für die Phytotherapie bei Tieren. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2018;10:589–595. doi: 10.17236/sat00178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lans C., Turner N., Khan T., Brauer G. Ethnoveterinary medicines used to treat endoparasites and stomach problems in pigs and pets in British Columbia, Canada. Vet. Parasitol. 2007;148:325–340. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lans C. Possible similarities between the folk medicine historically used by First Nations and American Indians in North America and the ethnoveterinary knowledge currently used in British Columbia, Canada. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;192:53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauber K., Wagner G. Haupt Verlag, Bern; Stuttgart, Wien: 2007. Flora Helvetica. [Google Scholar]

- Leonti M., Verpoorte R. Traditional mediterranean and european herbal medicines. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017;199:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löscher W., Richter A., Potschka H., editors. Pharmakotherapie bei Haus- und Nutztieren. Verlag Enke bei Thieme; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maeschli A., Schmidt A., Ammann W., Schurtenberger P., Maurer E., Walkenhorst M. Einfluss eines komplementärmedizinischen telefonischen Beratungssystems auf den Antibiotikaeinsatz bei Nutztieren in der Schweiz. Complement. Med. Res. 2019 doi: 10.1159/000496031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall B.M., Levy S.B. Food animals and antimicrobials: impacts on human health. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011;24:718–733. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00002-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M., Vogl C.R., Amorena M., Hamburger M., Walkenhorst M. Treatment of organic livestock with medicinal plants: a systematic review of European ethnoveterinary research. Forschende Komplementärmed. 2014;21:375–386. doi: 10.1159/000370216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M., Zbinden M., Vogl C.R., Ivemeyer S., Meier B., Morena M., Maeschli A., Hamburger M., Walkenhorst M. Swiss ethnoveterinary knowledge on medicinal plants – a within-country comparison of Italian speaking regions with north-western German speaking regions. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017;13:1. doi: 10.1186/s13002-016-0106-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCorkle C. An introduction to ethnoveterinary research and development. J. Ethnobiol. 1986;6:129–149. [Google Scholar]

- Mendel M., Chłopecka M., Dziekan N., Karlik W. Modification of abomasum contractility by flavonoids present in ruminants diet: in vitro study. Animal. 2016;10:1431–1438. doi: 10.1017/S1751731116000513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez-Baceta G., Aceituno-Mata L., Reyes-Garcia V., Tardio J., Salpeteur M., Pardo-de-Santayana M. The importance of cultural factors in the distribution of medicinal plant knowledge: a case study in four Basque regions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;161:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver S.P., Murinda S.E., Jayarao B.M. Impact of antibiotic use in adult dairy cows on antimicrobial resistance of veterinary and human pathogens: a comprehensive review. Foodb. Pathog. Dis. 2011;8:337–355. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni A., Howard P., Volpato G., Santoro R.F. Natural remedies and nutraceuticals used in ethnoveterinary practices in inland southern Italy. Vet. Res. Commun. 2004;28:55–80. doi: 10.1023/b:verc.0000009535.96676.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni A., Giusti M., de Pasquale C., Lenzarini C., Censorii E., Gonzales-Tejero M., Sanchez-Rojas C., Ramiro-Gutierrez J., Skoula M., Johnson C., Sarpaki A., Della A., Paraskeva-Hadijchambi D., Hadjichambis A., Hmamouchi M., El-Jorhi S., El-Demerdash M., El-Zayat M., Al-Shahaby O., Houmani Z., Scherazed M. Circum-Mediterranean cultural heritage and medicinal plant uses in traditional animal healthcare: a field survey in eight selected areas within the RUBIA project. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2006;2:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponepal V., Spielberger U., Riedel-Caspari G., Schmidt F.W. Use of a Coffea arabica tosta extract for the prevention and therapy of polyfactorial infectious diseases in newborn calves. [Einsatz eines Coffea arabica tosta Extrakts zur Prophylaxe und Therapie polyfaktorieller Infektionskrankheiten neugeborener Kälber.] Dtsch. Tierärztliche Wochenschr. (DTW) 1996;103:390–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poutaraud A., Guilloteau L., Gros C., Lobstein A., Meziani S., Steyer D., Miosan M.P., Foury A., Lansade L. Lavender essential oil decreases stress response of horses. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018;16:539–544. [Google Scholar]

- Reichling J., Gachnian-Mirtscheva R., Frater-Schröder M., Saller R., Fitzi-Rathgen J., Widmaier W. Springer Verlag; Heidelberg: 2016. Heilpflanzenkunde für die Veterinärparxis. [Google Scholar]

- Ryhner T., Meier B., Walkenhorst M. Arzneipflanzen im Berner Pferdestall: erfahrungswissen von Pferdehaltern. Complement. Med. Res. 2018;25:331–337. doi: 10.1159/000493035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambraus H.H. Ulmer; Stuttgart: 1996. Atlas der Nutztierrassen, 250 Rassen in Wort und Bild. [Google Scholar]

- Schäffer J. "Phytotherapie-Zukunft braucht Vergangenheit" - Proceedings der 25. Schweizerischen Jahrestagung für Phytotherapie. 2010. In ein Fass voll Tobakslauge/Tunkt man ihn mit Haut und Haar“ – geschichte und Zukunft der Phytotherapie in der Tierheilkunde.www.smgp.ch/smgp/homeindex/jahrestagungf/2010/abstracts/schaeffer.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer A.M., Motti R., Weckerle C.S. Traditional plant use in the areas of monte vesole and ascea, cilento national park (campania, southern Italy) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97:129–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid K., Ivemeyer S., Vogl C., Klarer F., Meier B., Hamburger M., Walkenhorst M. Traditional use of herbal remedies in livestock by farmers in 3 Swiss cantons (Aargau, Zurich, Schaffhausen) Forschende Komplementärmed. 2012;19:125–136. doi: 10.1159/000339336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder P., Schonecker L., Schüpbach-Regula G., Meylan M. Effects of management practices, animal transport and barn climate on animal health and antimicrobial use in Swiss veal calf operations. Prev. Vet. Med. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2019.03.007. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebai H., Jabri M.A., Souli A., Rtibi K., Selmi S., Tebourbi O., El-Benna J., Sakly M. Antidiarrheal and antioxidant activities of chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) decoction extract in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014;152:327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StAR, Strategie Antibiotikaresistenzen Schweiz 2015. www.star.admin.ch/star/de/home/star/strategie-star.html 1–78. last visit of the website 16.03.2019.

- Stucki K., Dal Cero M., Vogl C.R., Ivemeyer S., Meier B., Maeschli A., Hamburger M., Walkenhorst M. Ethnoveterinary contemporary knowledge of farmers in pre-alpine and alpine regions of the Swiss cantons of Bern and Lucerne compared to ancient and recent literature – is there a tradition? J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019;234:225–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tresch M., Mevissen M., Ayrle H., Melzig M.-F., Roosje P., Walkenhorst M. Medicinal plants as therapeutic options for topical treatment in canine dermatology? A systematic review. BMC Vet. Res. 2019 doi: 10.1186/s12917-019-1854-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uncini Manganelli R., Camangi F., Tomei P. Curing animals with plants: traditional usage in Tuscany (Italy) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001;78:171–191. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Boeckel T.P., Brower C., Gilbert M., Grenfell B.T., Levin S.A., Robinson T.P., Teillant A., Laxminarayan R. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015;112:5649–5654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503141112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viegi L., Pieroni A., Guarrera P., Vangelisti R. A review of plants used in folk veterinary medicine in Italy as basis for a databank. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003;89:221–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]