Abstract

Previous evidence suggests that a homeostatic germinal center (GC) response may limit bortezomib desensitization therapy. We evaluated the combination of costimulation blockade with bortezomib in a sensitized non-human primate kidney transplant model. Sensitized animals were treated with bortezomib, belatacept, and anti-CD40 mAb twice weekly for a month (n = 6) and compared to control animals (n = 7). Desensitization therapy–mediated DSA reductions approached statistical significance (P = .07) and significantly diminished bone marrow PCs, lymph node follicular helper T cells, and memory B cell proliferation. Graft survival was prolonged in the desensitization group (P = .073). All control animals (n = 6) experienced graft loss due to antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) after kidney transplantation, compared to one desensitized animal (1/5). Overall, histological AMR scores were significantly lower in the treatment group (n = 5) compared to control (P = .020). However, CMV disease was common in the desensitized group (3/5). Desensitized animals were sacrificed after long-term follow-up with functioning grafts. Dual targeting of both plasma cells and upstream GC responses successfully prolongs graft survival in a sensitized NHP model despite significant infectious complications and drug toxicity. Further work is planned to dissect underlying mechanisms, and explore safety concerns.

Keywords: alloantibody, animal models: nonhuman primate, basic (laboratory) research/science, desensitization, immunosuppressant - fusion proteins and monoclonal antibodies: costimulation molecule specific, immunosuppression/immune modulation, kidney transplantation/nephrology, plasma cells

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Sensitization to human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) affects 30% of patients currently on the kidney waiting list.1 Desensitization treatments have proven effective at lowering the risk of hyperacute rejection.2–4 Early results also suggest acceptable 1-year graft survival despite high rejection rates.5–7 Desensitized patients increase their chance of transplantation compared to remaining on the waiting list until a compatible match is found.8 However, current desensitization strategies have known limitations. First, long-term graft survival of desensitized recipients remains inferior to nonsensitized counterparts6,9,10 due to an increased rate of anti-HLA and donor-specific antibodies (DSAs) that correlate with chronic transplant glomerulopathy and allograft vasculopathy. Additionally, the current methods of desensitization are prone to antibody rebound. The incomplete durability of these therapies may be due to the failure to address the relevant sources of antibody in sensitized patients, such as long-lived plasma cells (PCs) in the secondary lymphoid organs and bone marrow (BM).

A new class of drugs called proteasome inhibitors has demonstrated the capability of preferentially eliminating PCs. The first drug of this class, bortezomib, was approved for the treatment of refractory multiple myeloma and induces apoptosis in PCs through the inhibition of the 26S proteasome.11 The disruption of proteasome function inhibits both malignant cells and conventional PCs.12,13 Bortezomib has shown promise in treatment of acute antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) following kidney transplantation14,15 and has recently been tested for desensitization .4,16 Although initially promising results were reported,17,18 recent clinical studies have indicated lack of efficacy in late AMR and in desensitization for lung transplantation candidates.19,20

We have previously established a rigorous model of sensitized nonhuman primate (NHP) kidney transplantation that closely mimics the human situation.21 We demonstrated that bortezomib monotherapy was able to reduce PCs, but DSA levels did not decrease, potentially due to induced germinal center (GC) B cell and Tfh expansion in the lymph nodes (LNs), suggesting humoral compensation.22 We therefore hypothesized that combining bortezomib with costimulation blockade (CoB) to inhibit upstream GC responses would lead to efficient and durable desensitization and promote long-term graft survival after kidney transplantation.

2 |. RESULTS

2.1 |. Sensitization in non-human primate model

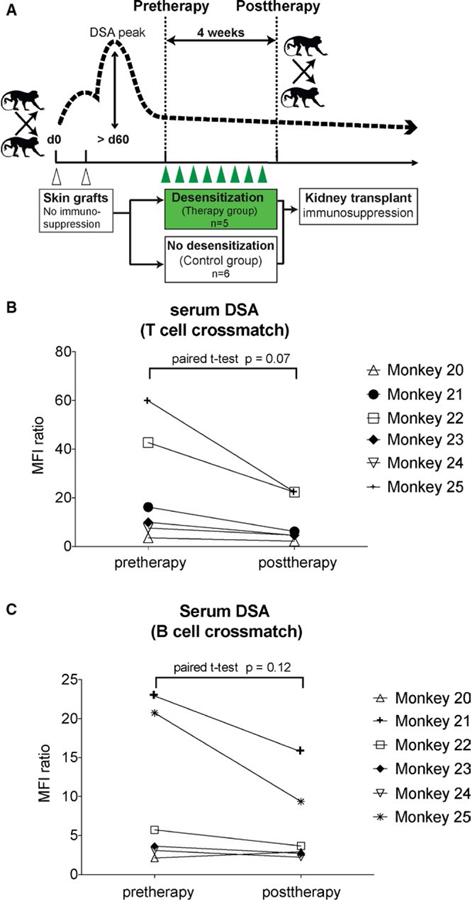

Thirteen rhesus macaques were sensitized via two skin grafts separated by >6 weeks from maximally MHC-mismatched donors (Figure 1A). Skin transplants were uniformly rejected. Retrospectively, serum DSA (Table 1) showed a peak median MFI ratio of 36.6 ± 22.3 in the control group versus 45.2 ± 19.8 in the treatment group for T cell and 23.0 ± 12.5 versus 27.1 ± 15.9 for B cell crossmatches, respectively. There was no difference in sensitization between the two groups (P = .5 and .6). The comparison of antibody load prior to transplantation was equivalent (9.6 ± 6.6 versus 9.9 ± 9.5 for T cell and 6.6 ± 3.0 versus 6.2 ± 5.4 for B cell crossmatches, P = .9 and .9). Thus, animals were uniformly sensitized.

FIGURE 1.

Preformed donor-specific antibody is reduced after costimulation blockade and proteasome inhibitor treatment. (A) Schematic representation of skin transplant for sensitization, immune-stabilization phase, desensitization treatment, or no treatment (control group) over 4 weeks and subsequent kidney transplantation under immunosuppression. (B and C) DSA levels in individual animals after desensitization. T and B cell crossmatches are showing a decrease of DSA after desensitization treatment. Serum from desensitized animals were collected and IgG DSA was quantified in a flow crossmatch. T cell crossmatches showed a strong trend of reduction of DSA in treatment animals. Data presented as MFI ratio compared to preskin transplant DSA level

TABLE 1.

Flow-crossmatch results after sensitization with two skin grafts (sensitization parameters of sensitized nonhuman primate)

| Animal | DSA T cell XM (MFI ratio) | DSA B cell XM (MFI ratio) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | highest | at transplant | highest | at transplant | ||

| Monkey 5 | 52.7 | 5.9 | 19.8 | 6.4 | ||

| Monkey 6 | 75.1 | 21.4 | 45.5 | 8.6 | ||

| Monkey 7 | 26.3 | 8.2 | 15.9 | 5.1 | ||

| Monkey 8 | 28.9 | 6.2 | 34.4 | 7.8 | ||

| Monkey 9 | 18.6 | 2.9 | 9.4 | 2.2 | ||

| Monkey 10 | 44.3 | 16.1 | 18.7 | 4.5 | ||

| Monkey 11 | 10.2 | 6.8 | 17.3 | 11.4 | ||

| Therapy group | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||

| Monkey 20 | 37.6 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 15.7 | 2.1 | 2.9 |

| Monkey 21 | 53.2 | 16.2 | 6.2 | 42.4 | 22.9 | 15.8 |

| Monkey 22 | 47.9 | 42.7 | 22.3 | 10.3 | 5.7 | 3.7 |

| Monkey 23 | 33.5 | 10.0 | 4.6 | 28.1 | 3.6 | 3.7 |

| Monkey 24 | 20.8 | 6.4 | 3.4 | 16.5 | 2.7 | 1.8 |

| Monkey 25 | 78.3 | 60.0 | 22.4 | 49.6 | 20.7 | 9.4 |

MFI ratio, MFI fold increase to baseline level; DSA, donor-specific antibodies; XM, Crossmatch; pre/post, before/after desensitization.

2.2 |. Beneficial effect of bortezomib with costimulation blockade in desensitization

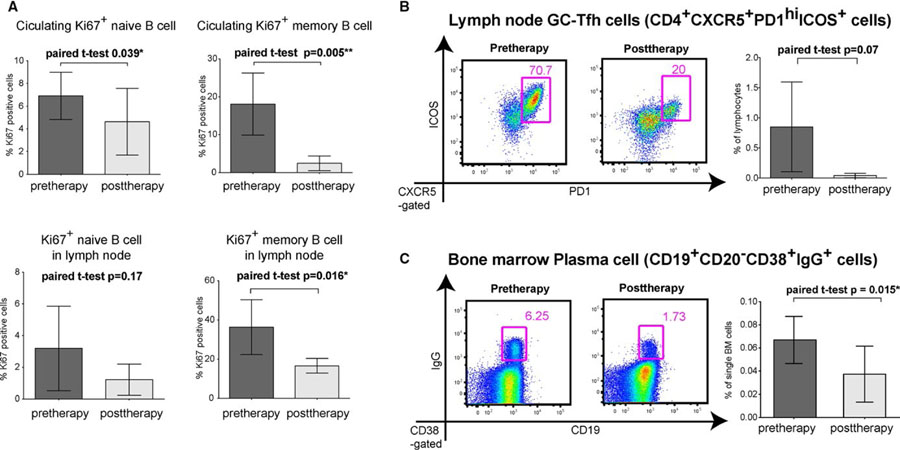

There were no adverse events during desensitization therapy with bortezomib (1.3 mg/m2) and CoB (20 mg/kg belatacept and 20 mg/kg 2C10.R4) for one month, but some monkeys had a loss of appetite, a consistent observation with bortezomib monotherapy reported previously.22 We evaluated the reduction of MFI ratio in T and B cell FXMs and found that after 4 weeks of therapy, the DSA MFI ratio had decreased by a mean of 52% ± 10% and 24% ± 32% in T and B cell crossmatches (P = .07 and .12; Figure 1B,C). We also analyzed immune cells related to the humoral response before and after desensitization. We found that circulating naïve (CD27−IgD+CD20+) and memory (CD27+IgD−CD20+) B cells did not change in frequency during treatment (Figure S1). However, proliferating B cells measured by Ki67 staining were decreased in the blood (P = .005) and LNs (P = .016; Figure 2A). Since this may indicate suppression of GC-driven B cell expansion, we evaluated Tfh cell population in LNs. Specifically, we evaluated the change of frequency of CD4+PD1hi and CD4+CXCR5+ Tfh cells, as well as CD4+PD1hiCXCR5+ICOS+GC–related Tfh cells in the LNs. Following desensitization, CD4+PD1hi and CD4+CXCR5+ cells were significantly reduced (Figure S2), and CD4+PD1hiCXCR5+ICOS+Tfh decreased by 88.5% (P = .074; Figure 2B). Surprisingly, the combination of belatacept and 2C10R4 was able to suppress Tfh cells, even in allosensitized animals. In addition, CD19+CD20−CD38+IgG+PCs in BM were reduced by 45% (P = .015; Figure 2C). The combination of CoB with a PC-targeting agent, such as bortezomib, is able to suppress PC depletion-mediated GC activation.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of cell types involved in antibody-mediated rejection pre- and posttherapy. (A) Proliferating B cells after desensitization. Circulating Ki67+ naïve and memory B cells were decreased significantly while only Ki67+ memory B cells were decreased in the lymph node. (B) Follicular helper T cells (Tfh) populations in the lymph nodes after desensitization. The germinal center Tfh cells (CD4+CXCR5+PD-1hiICOS+) were significantly reduced in the lymph node after desensitization. (C) Plasma cell population from bone marrow biopsies after desensitization. Bone marrow plasma cells (CD19+CD20−CD38+IgG+) were significantly reduced after desensitization. Data present mean ± SD of six animals before and after desensitization

2.3 |. Desensitization with bortezomib and costimulation blockade prolonged graft survival

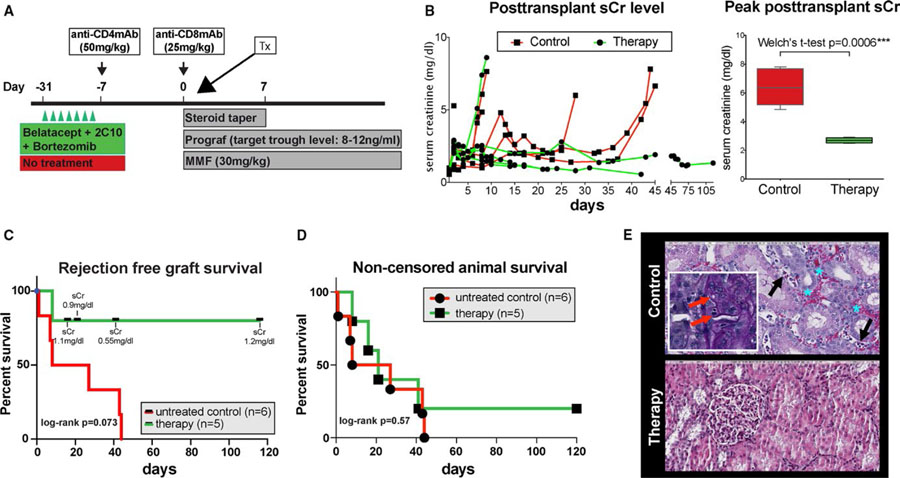

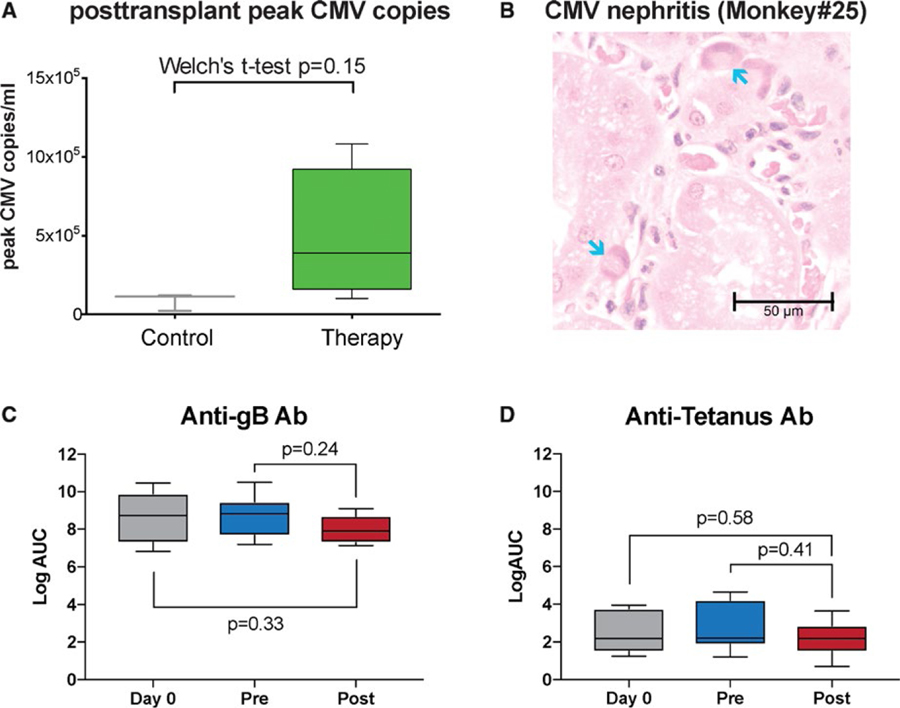

All animals underwent life-sustaining kidney transplantation using a kidney from their previous completely HLA-mismatched skin donor. As previously reported, basiliximab induction was not capable of controlling the immediate posttransplant memory T cell response.21 Therefore, anti-CD4 and -CD8 monoclonal antibodies were used for induction followed by maintenance immunosuppression with tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and a steroid taper (Figure 3A). Whereas all monkeys in the control group showed early humoral rejection, as reported previously,21 in the dual therapy (CoB +bortezomib) group only one rejection occurred (monkey 23), showing features of AMR and thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) on postoperative day (POD) 8. All other animals maintained excellent kidney function with a mean serum creatinine (sCr) at sacrifice of 0.97 ± 0.33 mg/dL (normal range 0.8–2.3 mg/dL) and a mean peak sCr of 2.70 ± 0.18 mg/dL and maintained low level of sCr over time. Contrarily, the control group demonstrated markedly elevated mean peak sCr of 6.38 ± 1.22 (P = .0004; Figure 3B). Mean graft survival was prolonged over 40 ± 44 days in the dual therapy group compared to 22 ± 19 days in the control (P = .073) with less antibody-mediated injuries including TMA (Figure 3C,E). However, noncensored recipient survival was not different (Figure 3D). As shown in Table 2, despite excellent graft function, animals in the dual therapy group accrued non-rejection complications limiting their survival. One animal (monkey 21), developed an atonic bladder, resulting in urosepsis and bladder empyema with Enterococcus faecium and Escherichia coli. Nevertheless, kidney function remained stable. Another animal (monkey 22) experienced BM suppression, resulting in refractory anemia and neutropenia. This myelosuppression was temporally associated with cytomegalovirus (CMV) viremia, ganciclovir therapy, and graft CMV infection. The animal was sacrificed after three blood transfusions per protocol requirements. Again, kidney function was not compromised. A third animal (monkey 25) lost weight and exhibited sepsis. At necropsy, a mesenteric abscess was present and Klebsiella pneumoniae was cultured. The last animal (monkey 24) survived until the end of the study period (>100 days) without evidence of kidney dysfunction. All monkeys reactivated CMV to varying degrees and were treated with ganciclovir. Monkeys receiving desensitization therapy pretransplant had a trend toward higher CMV copies posttransplant (mean peak CMV copies/mL 85 × 103 ± 54 × 103 control vs. 550 × 103 ±531 × 103 therapy; P = .18; Figure 4A). Although rare CMV+ cells were seen in the graft of one control monkey, three of five desensitized monkeys showed CMV nephritis (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 3.

Desensitization with costimulation blockade and proteasome inhibitor prolongs renal allograft survival in sensitized non-human primates. (A) Dosing regimen of desensitization, T cell depletion induction and maintenance immunosuppression for kidney transplantation in the sensitized monkeys. (B) Serum creatinine level after kidney transplantation. Compared with control, sensitized animals treated with belatacept, 2C10R4 and bortezomib for desensitization showed well-maintained sCr level over time and significantly lower posttransplant peak sCr level. (C) Rejection-free graft survival: therapy versus control group. The longest survivor of control group succumbed to rejection on day 43. In the treatment group, animals had to be censored due to non–kidney-related complications, but sCr was excellent at end points. Log-rank test shows a nonsignificant tendency of better survival with treatment. (D) Noncensored animal survival: therapy versus control group. Death noncensored animal survival shown in days by control and therapy group. Log-rank test comparing animals without desensitization (red line) versus receiving dual targeting therapy (green line) determined P values. (E) Representative histology from untreated control and desensitized animals. Untreated control has peritubular capillaritis (black arrow) and red blood cells in peritubular capillaries and the interstitium (blue asterisk) (original magnification: 200×). It also showed glomerulitis with an occlusion of glomerular capillary loops and segmental glomerular basement membrane duplication (red arrow in inset) (original magnification, 400×). Desensitized animal has interstitial inflammation with severe tubulitis but no glomerulitis or peritubular capillaritis and has areas devoid of inflammation, also revealing no glomerultiis or peritubular capillaritis (original magnification: 200×)

TABLE 2.

Treatment, outcomes, and reason for sacrifice in controls and desensitized animals

| Animal |

Desensitization |

Immunosuppression |

Survival (days) |

Complication/reason for sacrifice |

Serum creatinine at sacrifice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bortezomib (n = 2) |

BTZ (3.5 mg/kg) |

NA |

NA |

Cardiopulmonary complications (death <48 h) |

NA |

| Bortezomib (n = 4) | BTZ (1.3 mg/m2) | NA | NA | Lost appetite | NA |

| Control (n = 6) | |||||

| Monkey 7a | none | Ind/TAC/MMF/Ster | 1 | Unknown, kidney failure | 10.2 |

| Monkey 6 | none | Ind/TAC/MMF/Ster | 1 | Kidney failure, hyperacute rejection | 5.28 |

| Monkey 8 | none | Ind/TAC/MMF/Ster | 7 | Kidney failure, rejection | 4.85 |

| Monkey 11 | none | Ind/TAC/MMF/Ster | 8 | Kidney failure, rejection | 7.64 |

| Monkey 9 | none | Ind/TAC/MMF/Ster | 27 | Kidney failure, rejection | 6.0 |

| Monkey 10 | none | Ind/TAC/MMF/Ster | 43 | Kidney failure, rejection | 7.81 |

| Monkey 5 | none | Ind/TAC/MMF/Ster | 44 | Kidney failure, rejection | 6.65 |

| Therapy (n = 5) | |||||

| Monkey 20a | Bela/2C10/BTZ | Ind/TAC/MMF/Ster | 1 | Kidney failure, graft thrombosis | |

| Monkey 23 | Bela/2C10/BTZ | Ind/TAC/MMF/Ster | 8 | Kidney failure, rejection | 8.6 |

| Monkey 21 | Bela/2C10/BTZ | Ind/TAC/MMF/Ster | 16 | Urosepsis, monkey condition | 1.1 |

| Monkey 25 | Bela/2C10/BTZ | Ind/TAC/MMF/Ster | 21 | Anemia, bone marrow depletionb | 0.9 |

| Monkey 22 | Bela/2C10/BTZ | Ind/TAC/MMF/Ster | 41 | Retroperitoneal abscess | 0.55 |

| Monkey 24 | Bela/2C10/BTZ | Ind/TAC/MMF/Ster | >120 | No complication, end of study | 1.33 |

Ind, induction; TAC, tacrolimus, MMF; mycophenolate mofetil; Ster, steroids.

Monkey 7 and monkey 20 were excluded from posttransplant analysis.

Monkey 25 received three blood transfusions posttransplant for anemia.

FIGURE 4.

Animals with dual targeting desensitization show increased level of CMV reactivation, CMV nephritis but antibody against CMV or tetanus were not compromised. (A) Increased risk of CMV infection with desensitization. CMV copies at the time of peak showed a strong trend of increase after desensitization compared to untreated animals. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin shows characteristic cytomegalovirus intranuclear inclusions (arrows) in peritubular capillary endothelial cells from desensitized animals. No changes in the level of anti-gB IgG (C) and the level of anti-TT (tetanus) IgG (D) compared to pretreatment or before sensitization

2.4 |. Alleviation of antibody-mediated rejection after desensitization with bortezomib with costimulation blockade

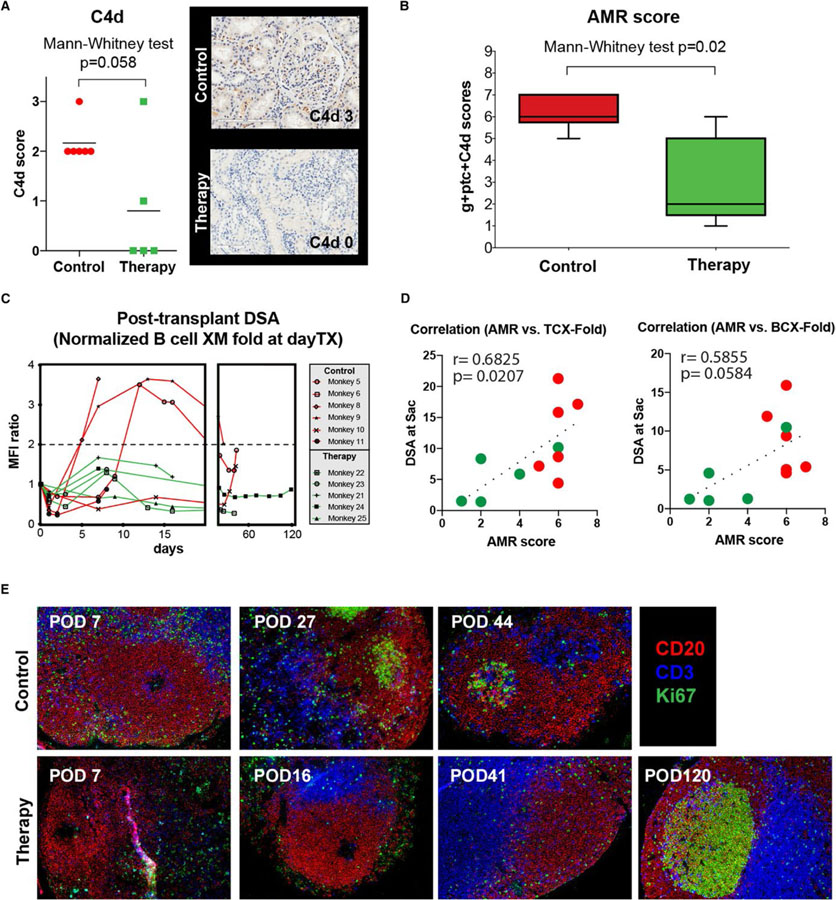

In addition to renal allograft function assessed by sCr, grafts were evaluated by biopsy for indication and at necropsy. Results were scored in blinded fashion using Banff criteria.23,24 Complete Banff grading for individual monkey biopsies is shown in Table 3. Control samples showed various degrees of rejection featuring signs of microvascular inflammation, namely glomerulitis (Banff g-score) and peritubular capillaritis (Banff ptc-score). The threshold for microvascular inflammation suspicious of AMR per Banff criteria (g + ptc ≥2) was surpassed in all control animals (median 4; IQR 3–4.25), but not desensitized animals (median 2; IQR 0.5–2.5). C4d staining was positive in all control animals. However, only one specimen stained convincingly after desensitization (Figure 5A). We calculated an AMR score from the ordinal numeric variables of g + ptc +C4d resulting in a median of 6 (IQR 5.75–7) in control animals (Table 4). Desensitized monkeys showed a lower median score of 2 (IQR 1–5; P = .02; Figure 5B). In treated animals, posttransplant DSA remained low (less than twofold increase compared to pretransplant nadir) whereas in some control monkeys, strong rebounds were seen (Figure 5C). In accordance with this, calculated AMR score shows a strong positive correlation to circulating DSA level at sacrifice (r = 0.68 and P = .02 for T cell FXM; r = 0.59 and P = .058 for B cell FXM, Figure 5D) from both untreated control and desensitized animals. This suggests an impact of the desensitization on AMR via lowering the DSA level. Notably, both animals showed a similar pattern of GC contraction (decreased Ki67+ area within CD20 B cell follicles) after T cell depletion or kidney transplantation. As shown in Figure 4E, GC staining appeared earlier in control animals compared to desensitized recipients. Interestingly, a recipient with no DSA showed hyperplastic germinal center staining at POD 120 after desensitization. This suggests the desensitization strategy suppressed GC reconstitution after T cell depletion, but allowed GC responses later with a lack of antidonor antibody response.

TABLE 3.

BANFF gradings of graft at the time of sacrifice

| Animal | Nves | %i | %ci | %ct | t | v | i | g | ci | ct | cg | mm | cv | ah | Ptc | Tubular injury | Interstitial plasma cells | Interstitial neutrophils | Interstitial eosinophils | Edema | Inclusions | PTC fibrin | Glomerular fibrin | Arteriole fibrin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 7) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monkey 5 | 20 | 40 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Monkey 6 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Monkey 7a | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Monkey 9 | 10 | 20 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Monkey 8 | 15 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Monkey 10 | 10 | 30 | 20 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Monkey 11 | 15 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Therapy (n = 6) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monkey 20a | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Monkey 21 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Monkey 23 | 10 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Monkey 22 | 25 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Monkey 25 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Monkey 24 | 15 | 40 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Monkey 7 and monkey 20 were excluded from posttransplant analysis.

FIGURE 5.

Posttransplant DSA and antibody-mediated rejection was significantly alleviated with costimulation blockade and proteasome inhibitor based desensitization. (A) C4d deposition in renal biopsies taken at the time of rejection after transplant. Animals treated with desensitization showed lower C4d score. (B) Antibody-mediated rejection score (Banff g + ptc + C4d) in end-of-study histology samples. Animals treated with desensitization treatment showed lower AMR scores than control animals. (C) Comparison of posttransplant course of DSA (normalized to prerenal transplant value = 1). Animals with desensitization did not show increased serum DSA. (D) Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated between DSA (at sacrifice) by T cell and B cell flow crossmatch to the calculated AMR score. Circulating DSA at sacrifice from both control and desensitized animals showed strong correlation (r = 0.68 and P = .02 for T cell FXM; r = 0.59 and P = .058 for B cell FXM) to the AMR score. (E) Representative immunofluorescence image of GC staining with CD3 (blue), CD20 (red), and Ki67 (green) in mesenteric and peripheral lymph node sections. Lymph nodes were collected at sacrifice (peripheral LNs)

TABLE 4.

Outcome in control and therapy group of sensitized monkeys after kidney transplantation. (Posttransplant histology; comparison treatment group/control group; in order of survival time)

| Animal | Survival (d) | ACR | AMR score (Banff) | Other indications | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 6)a | g | ptc | C4d | total | |||

| Monkey 5 | 44 | borderline | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | AMR, borderline AR |

| Monkey 6 | 1 | none | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | AMR, TMA, hyperacute rejection |

| Monkey 8 | 7 | none | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 | AMR, TMA |

| Monkey 9 | 27 | borderline | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | AMR, borderline AR |

| Monkey 10 | 43 | Banff IIB | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | AMR + ACR |

| Monkey 11 | 8 | none | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | AMR, TMA |

| AMR score median 6 (IQR 5.75−7) | |||||||

| Therapy (n = 5)b | |||||||

| Monkey 23 | 8 | none | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | AMR, TMA |

| Monkey 21 | 16 | none | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | CMV + nephritis |

| Monkey 25 | 21 | none | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | AMR, CMV + nephritis |

| Monkey 22 | 41 | none | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | CMV + nephritis |

| Monkey 24 | >120 | Banff IB | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ACR1B |

| AMR score median 2 (IQR 1−5) | |||||||

AR, acute rejection; AMR, antibody-mediated rejection; g, glomerulitis; ptc, peritubular capillary inflammation; C4d, C4d deposition in walls of peritubular capillaries (immunohistochemistry); TMA, thrombotic microangiopathy; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

Monkey 7 (POD3) is excluded from control.

Monkey 20 (POD0) is excluded from therapy group for technical complications.

3 |. DISCUSSION

In this study we tested the effect of dual targeting of germinal centers with CoB and plasma cells (or antibody-secreting cells) with bortezomib as a desensitization strategy in a highly sensitized model of kidney transplantation. The monkeys were sensitized by repeated (two sequential) skin grafts from a maximally MHC-mismatched donor. Following stabilization of DSA levels, we desensitized six rhesus macaques with a four-week course of bortezomib, belatacept, and anti-CD40 mAb (2C10.R4). In order to confirm the durability of desensitization, we performed kidney transplantation using a graft from the previous skin donor. Such direct potent sensitization of non-human primate recipients using two skin grafts from the future kidney donor creates a far higher immunological barrier than human patients would be expected to encounter from a donor kidney to which they are sensitized. In an effort to develop a model that is relevant to the human situation, we intentionally tested desensitization in a highly MHC-immunized host to assess efficacy of treatment strategies.

Desensitization with CoB and bortezomib showed a trend toward reduction of DSA by T cell crossmatch, but no statistical significance was achieved (Figure 1). The results of B cell crossmatch were more variable, with one monkey actually showing an increase in DSA. Similarly, human data show different effects of bortezomib on MHC class I and II antibodies, including a greater resistance to desensitization of some MHC class II DSAs.25 Another explanation is a potential assay-related underestimation of the DSA decline, as background luminescence is stronger in B cell FXM than in T cell FXM,26,27 resulting in higher baseline MFI and therefore a smaller change. Furthermore, we alloimmunized animals twice with two skin transplantations prior to receiving a kidney from the same donor. This repeated immunization produces high levels of donor-specific sensitization and makes reducing the level of DSA a significant challenge. In our parallel study with single allo-skin sensitization, the same regimen reduced the DSA level significantly.28 Nevertheless, the DSA reduction contrasted with data using bortezomib monotherapy (Table S1), which showed profound BM PC reduction but no DSA decrease.22 In addition, treatment with bortezomib alone resulted in rebound GC response including increased class-switched B cell proliferation and Tfh cells.22

Belatacept and anti-CD40mAb have been shown to prevent antigen-specific antibody formation in small animals29,30 and in nonsensitized transplant recipients.31 We have seen similar effects from belatacept/2C10.R4 on de novo DSA production and GC responses in a NHP model of de novo AMR.32 Furthermore, belatacept also showed its unique ability of controlling humoral response in transplant patients.33 However, the expected impact of CoB was minimal in the sensitized setting since activated or memory T cells are not costimulation-dependent. However, the addition of CoB with bortezomib therapy results in decreased memory B cell proliferation and Tfh cells (Figure 2). This suggests successful suppression of compensatory replenishment of memory B and PC levels after proteasome inhibition–related apoptosis.22,34 It is not clear whether CoB directly suppressed Tfh cells or whether this was secondary to B cell suppression, since T/B cell interaction in the GC is bidirectional. The effect of CTLA4-Ig on B cells and memory B cells has been recognized.35 Our observation could be due to an additional effect of belatacept and 2C10.R4 on PC depletion since CD28 has been found to be an important pro-survival factor for murine BM long lived plasma cells (LLPCs)36,37 and human myeloma cells.36 Furthermore, anti-CD40 treatment in a murine model has been shown to arrest PC development from naïve B cells and to irreversibly down-regulate BLIMP1.30 However, CoB without bortezomib did not reduce BM PCs in sensitized animals.28 We did find a reduction of CD19+CD20−CD38+IgG+cells in BM with combined bortezomib and CoB (Figure 2D). This cell marker combination includes LLPCs and excludes short-lived plasmablasts (CD20+, more frequently IgG−).38 A reduction of PCs without rebound GC response might explain the decrease of DSA production following desensitization. Interestingly, proliferating B cell and GC-Tfh (CD4+PD-1hiCXCR5+ICOS+) cell populations in the LN rebounded after kidney transplantation (Figure S3). Since there was no obvious DSA rebound, these populations may not be specific for donor antigen.

Control animals uniformly rejected their grafts despite conventional immunosuppression. In the desensitized group, we demonstrate favorable kidney function with prolonged graft survival and only one rejection. This single rejection episode may have been due to residual DSA despite dramatic reduction of DSA after desensitization with COB and PI. Clinically, this could be prevented by combining treatments to target existing DSA such as plasmapheresis, IVIG, or IdeS.39

Unfortunately, sacrifice was necessary in three of four of long-term surviving desensitized animals after kidney transplantation with good graft function (sCr: 0.55 ~ 1.1) in the absence of rejection, possibly as a result of viral reactivation (detailed reasons for sacrifice described in Table 2). Clearly, this raises concerns about the toxicity of the regimen with respect to protective immunity. However, the anti-gB (CMV) antibody level was not affected by dual targeting (Figure 4C). It is also possible that no changes in anti-CMV antibody response could be due to reactivation of CMV caused by desensitization itself. Therefore, we also measured anti-tetanus Ab. Unlike CMV, re-infection with tetanus is very unlikely and all of our monkeys were treated with tetanus vaccine during quarantine. As shown in Figure 4D, anti-tetanus Ab was not affected by our desensitization. This observation suggests that dual targeting desensitization does not abrogate protective humoral immunity. Dual desensitization therapy for four weeks followed by posttransplant anti-CD4, anti-CD8 mAbs, and conventional triple immunosuppression may be too profoundly immunosuppressive for animals to tolerate. We believe that complete CD8 T cell depletion by monoclonal antibody would be the likely explanation of ineffective control of CMV after kidney transplantation rather than compromised of anti-CMV humoral responses. In accordance with this, the same regimen with basiliximab induction did not show any viral complication.28 Avoiding CD8 T cell depletion is a possible approach, however, it is unclear that cell-mediated rejection could be controlled without CD8 T cell depletion in the current NHP model. Instead, rhesus ATG (which was not previously available) could be a possible alternative since it depletes CD8 less profoundly and for a shorter period of time. Furthermore, rATG showed similar lymphocyte depletion to rabbit ATG (Thymoglobulin) in human patients and fewer viral complications in the nonhuman primate model (personal communication to Dr Kirk). This is also more translatable reflecting depletional induction by thymoglobulin in human patients. Nonetheless, CMV reactivation is a major concern in humans, as therapy is known to be difficult in patients after transplantation.40,41 The impact of desensitization on protective immunity remains poorly studied and will be a critical component in the design of future desensitization strategies.

Histological evidence of rejection was reduced in desensitized compared to control monkeys. Banff g- and ptc-scores, signs of microvascular inflammation, and C4d staining in kidney allografts were significantly lower in desensitized animals (Figures 3 and 5). Of note, histopathological grading (Table 4) might overestimate rejection especially in desensitized animals as CMV nephritis can show signs that are indistinguishable from rejection (eg, glomerulitis, peritubular capillaritis, tubulitis, etc).42–47 It has been reported that CMV tends to affect kidneys in one of three patterns, (a) CMV infection within the glomerular endothelial cells, (b) CMV infection within the tubular epithelia cells, or (c) CMV in endothelial cells of a peritubular capillary. Interestingly, we exclusively observe peritubular capillary CMV in the desensitized animals (Figure 4B). However, we were not able to find tubular and glomerular CMV. The posttransplant DSA level remained stable compared to control animals which showed rapid elevation of DSA (Figure 5C). Furthermore, circulating DSA strongly correlated with the calculated AMR scores (Figure 5D). These data suggest that de novo alloantibody is the driving force of graft rejection in the controls. Furthermore, the GC response correlated with DSA rebound, as GC reconstitution occurred early in control animals compared to desensitized recipients. Suppression of the GC after T cell depletion in the desensitized animals was prolonged (Figure 5E). We believe our study provides a proof of concept that PCs and the GC response represent appropriate targets required for durable desensitization. These therapies may be a necessary addition to current regimens which focus more narrowly on controlling circulating antibodies.

This study was our first attempt to include CoB in a desensitization strategy utilizing cytolytic induction in a large animal model. Treatment with bortezomib monotherapy is unlikely to result in a sustained reduction of DSA-producing PCs, as a result of GC compensation.22 However, we demonstrate that CoB can target this upstream GC response after bortezomib–induced PC apoptosis, leading to excellent kidney function and fewer signs of antibody-mediated injury by histology. These data suggest that the GC is an attractive target for mechanism-based desensitization. However, limitations of this therapy included compromised protective immunity and persistent low-grade antibody injury to the grafts. Future studies will require particular focus on refinement of GC and PC-targeting strategies to allow less aggressive induction and improved posttransplant maintenance immunosuppression in an effort to reduce opportunistic infection and off-target drug effects. Combining strategies for GC and PC-targeting with conventional desensitization regimens that remove circulating alloantibodies may hold promise for future translation into human protocols.

4 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1 |. Animal selection and care

All medications and procedures were conducted in accordance with National Institute of Health guidelines after approval by the Emory University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were obtained (Alpha Genesis Inc, Yemassee, SC) and paired by selecting for maximal disparity at MHC class I and II.

4.2 |. Sensitization by skin grafting, desensitization treatment

Full-thickness skin grafts from the dorsum were exchanged between donor–recipient pairs without immunosuppression. Maximally mismatching donor and recipient pairs were selected but monkey 5 (control), monkey 22 (therapy), and monkey 23 (therapy) shared MAMU A004/B012b, MAMUB012b, and MAMU B012b with their donor, respectively (Figure S4). This procedure was repeated approximately 6 to 10 weeks later. After a period to allow for DSA stabilization, six animals (monkeys 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, and 25) received a desensitization regimen consisting of 4 weeks of treatment with bortezomib 1.33 mg/m2 IV (half dose in monkeys 24 and 25; Velcade, Selleck Chemicals LLC, Houston, TX), belatacept 20 mg/kg IV (Nulojix, Bristol-Myers Squibb, NY), and recombinant anti-CD40 mAb 20 mg/kg IV (2C10R4; NIH Nonhuman Primate Reagent Resource, Boston, MA). Seven animals did not receive desensitization. Peripheral blood, BM, and lymph nodes were sampled and analyzed with flow cytometry in the desensitization group pre- and posttreatment.

4.3 |. Kidney transplantation, immunosuppressive and antiviral agents, clinical, graft, and immune monitoring

In all animals, swapping kidney transplantation with native bilateral nephrectomy was performed. Rhesus anti-CD4 mAb (CD4R1)50 mg/kg IV was administered 5 days before and rhesus anti-CD8 mAb (MT807R1) 25 mg/kg IV on the day of kidney transplantation (both NIH Nonhuman Primate Reagent Resource). Conventional triple immunosuppression with tacrolimus (IM twice daily, targeting trough levels of 8–12 ng/mL; Prograf®, Astellas Pharma, Northbrook, IL), mycophenolate mofetil (twice daily subcutaneously (SC) at 15 mg/kg or orally at 30 mg/kg; Cellcept®, Genentech, San Francisco, CA), and a methyprednisolone taper were administered (15 mg/kg IV at transplant and subsequently reduced daily by halves to 0.5 mg/kg IM for the rest of the postoperative period; Solumedrol®, Pfizer, New York, NY). Prophylactic ganciclovir for rhCMV reactivation was given at 6 mg/kg SQ daily, but was increased to twice daily if needed for therapy (Cytovene®, Fresenius Kabi, Lake Zurich, IL). Weekly phlebotomy was used to obtain complete blood counts, serum chemistries, and tacrolimus trough levels. Real-time PCR was performed to measure rhCMV and rhesus parvovirus reactivation. At necropsy, grafts were harvested, fixed, embedded, and stained as previously described.48 Histology was then evaluated blindly by a trained pathologist (ABF) and scored according to updated Banff criteria.23,24 One animal in both the control (monkey 7) and desensitization (monkey 20) groups suffered allograft loss unrelated to rejection and were excluded from the analysis of transplantation outcomes.

4.4 |. Detection of donor-specific antibodies (DSAs)

Alloantibody production was assessed by flow crossmatch (FXM) of donor PBMCs with serially collected recipient serum samples. 3 × 105 donor PBMCs were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with 10 µL recipient serum, washed, and stained with FITC-labeled anti-monkey IgG (KPL, Inc Gaithersburg, MD), PE-labeled anti-CD20 (2H7), and PerCP- Cy5.5-labeled anti-CD3 (SP34–2) (both BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA). Crossmatch positivity and “successful sensitization” was defined by a twofold increase of mean MFI from baseline levels (MFI-ratio ≥2). The runs were performed by ACG and CKB following a stringently standardized protocol utilizing the same reagents, settings, and flow cytometer. For pretransplant analysis, T cell crossmatches (representing MHC class I antibodies) were performed. Depleting CD4R1 antibody interfered with our secondary antibody for T cell crossmatch, so B cell crossmatches were used post transplantation.

4.5 |. Detection of anti-rhCMV gb and antitetanus antibodies

To measure the magnitude of rhesus gB-specific and tetanus toxoid-specific plasma IgG responses, 384-well ELISA plates were coated for 2.5 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C with 30 ng RhCMV gB (courtesy of Dr Mark Walters at the University of Alabama at Birmingham) or 30 ng tetanus toxoid (Creative Diagnostics) per well, then were blocked with assay diluent (1× PBS containing 4% whey, 15% normal goat serum, and 0.5% Tween-20). Threefold dilutions of sera were added to the plate, detected with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated mouse anti-monkey IgG (Southern Biotech), and developed using SureBlue Reserve tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) peroxidase substrate (KPL). Tetanus toxoid data are reported as log10 AUC (area under the curve) values, which indicate the magnitude of the area under the sigmoidal dilution vs. OD curve. AUC was chosen because full sigmoidal binding curves were not obtained, complicating ED50 determination.

4.6 |. Polychromatic flow cytometric analysis

Cells were stained with Live/Dead Fixable Aqua dead cell stain kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and then monoclonal antibodies (mAb) against human: CD3, CD4, CD8, CD14, CD20, CD25, CD27, CD28, CD56, CD95, CD159a, CD278 (ICOS), CD279 (PD-1), IgD, IgG, CXCR5, and, after fixation, Ki67 and FoxP3 (see Supporting Information for clones and providers). Samples were collected with a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and analyzed using FlowJo software vX (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). In terms of standardization the runs followed the same principles as runs for DSA.

4.7 |. Germinal center staining

In order to visualize germinal center, anti-human Ki67 (MM1, Vector, Burlingame, CA), anti-human CD20 (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), and human CD3 (CD3–12, AbD serotec, Raleigh, NC) with appropriate secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) and Hoechst 33342 were used. All images were acquired with Axio Imager Z1 microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) and analyzed by ZxioVs40 V4.8.1.0 program (Zeiss) and Image J1.43u (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

4.8 |. Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SD (error bars in graphs) or as otherwise indicated. Sample comparisons of different animals and/or time points were achieved with two-tailed (paired) t test in normally distributed data and (Mann-Whitney/) Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test otherwise. In case of unequal variances, we used Welch’s t test (15). One-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s test was used to compare multiple time points with baseline. For survival analysis, we used the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test. Values of P < .05 were considered to be statistically significant. We used Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) and SPSS 21 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding information

Austrian Science Fund, Grant/Award Number: J3414; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Grant/Award Number: U19AI051731; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

This work was supported by U19AI051731 (awarded to S.J.K.), part of the NIH NHP Transplantation Tolerance Cooperative Study Group sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. We would like to gratefully acknowledge the YNPRC (Yerkes National Primate Research Center) staff and the expert assistance of Dr. Elizabeth Strobert and Dr. Joe Jenkins for animal care; Pathology and histology support of Prachi Sharma and Deepa M. Kodandera. We would like to acknowledge the Emory Transplant Center biorepository for a weekly viral monitoring. Anti-CD4mAb, anti-CD8mAb, and anti-CD40mAb (2C10R4) used in this study were produced and provided by the Non-human Primate Reagent Resource (5R24OD010976, 1U24AI126683). C.K.B. received grant support by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): project J3414 and a research stipend by the Austrian Society of Surgery.

Abbreviations:

- AMR

antibody-mediated rejection

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- CoB

costimulation blockade

- DSA

donor-specific antibody

- FXM

flow crossmatch

- HLA

human leucocyte antigen

- IQR

interquartile range

- LLPC

long lived plasma cell

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- NHP

non-human primates

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PC

plasma cell

- POD

postoperative day

- PTC

peritubular capillaritis

- rhCMV

rhesus cytomegalovirus

- rhLCV

rhesus lymphocryptovirus

- sCr

serum creatinine

- Tfh

follicular helper T cells

- TMA

thrombotic microangiopathy

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2015 annual data report: kidney. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(suppl 1):21–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gloor JM, DeGoey SR, Pineda AA, et al. Overcoming a positive crossmatch in living-donor kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2003;3(8):1017–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riella LV, Safa K, Yagan J, et al. Long-term outcomes of kidney transplantation across a positive complement-dependent cytotoxicity crossmatch. Transplantation. 2014;97(12):1247–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartel G, Wahrmann M, Regele H, et al. Peritransplant immunoadsorption for positive crossmatch deceased donor kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(9):2033–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gloor JM, Winters JL, Cornell LD, et al. Baseline donor-specific antibody levels and outcomes in positive crossmatch kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(3):582–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haririan A, Nogueira J, Kukuruga D, et al. Positive cross-match living donor kidney transplantation: longer-term outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(3):536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordan SC, Tyan D, Stablein D, et al. Evaluation of intravenous immunoglobulin as an agent to lower allosensitization and improve transplantation in highly sensitized adult patients with end-stage renal disease: report of the NIH IG02 trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(12):3256–3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montgomery RA, Lonze BE, King KE, et al. Desensitization in HLA-incompatible kidney recipients and survival. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(4):318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bentall A, Cornell LD, Gloor JM, et al. Five-year outcomes in living donor kidney transplants with a positive crossmatch. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(1):76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marfo K, Lu A, Ling M, Akalin E. Desensitization protocols and their outcome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(4):922–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naujokat C, Berges C, Höh A, et al. Proteasomal chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity is required for essential functions of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Immunology. 2007;120(1):120–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perry DK, Burns JM, Pollinger HS, et al. Proteasome inhibition causes apoptosis of normal human plasma cells preventing alloantibody production. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(1):201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diwan TS, Raghavaiah S, Burns JM, Kremers WK, Gloor JM, Stegall MD. The impact of proteasome inhibition on alloantibody-producing plasma cells in vivo. Transplantation. 2011;91(5):536–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everly MJ, Everly JJ, Susskind B, et al. Bortezomib provides effective therapy for antibody- and cell-mediated acute rejection. Transplantation. 2008;86(12):1754–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh RC, Everly JJ, Brailey P, et al. Proteasome inhibitor-based primary therapy for antibody-mediated renal allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2010;89(3):277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woodle ES, Shields AR, Ejaz NS, et al. Prospective iterative trial of proteasome inhibitor-based desensitization. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(1):101–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.May LJ, Yeh J, Maeda K, et al. HLA desensitization with bortezomib in a highly sensitized pediatric patient. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18(8):E280–E282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeong JC, Jambaldorj E, Kwon HY, et al. Desensitization using bortezomib and high-dose immunoglobulin increases rate of deceased donor kidney transplantation. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95(5):e2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eskandary F, Regele H, Baumann L, et al. A randomized trial of bortezomib in late antibody-mediated kidney transplant rejection. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(2):591–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snyder LD, Gray AL, Reynolds JM, et al. Antibody desensitization therapy in highly sensitized lung transplant candidates. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(4):849–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burghuber CK, Kwun J, Page EJ, et al. Antibody-mediated rejection in sensitized nonhuman primates: modeling human biology. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(6):1726–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwun J, Burghuber C, Manook M, et al. Humoral compensation after bortezomib treatment of allosensitized recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(7):1991–1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haas M, Sis B, Racusen LC, et al. Banff 2013 meeting report: inclusion of c4d-negative antibody-mediated rejection and antibody-associated arterial lesions. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(2):272–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loupy A, Haas M, Solez K, et al. The Banff 2015 kidney meeting report: current challenges in rejection classification and prospects for adopting molecular pathology. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(1):28–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Philogene MC, Sikorski P, Montgomery RA, Leffell MS, Zachary AA. Differential effect of bortezomib on HLA class I and class II antibody. Transplantation. 2014;98(6):660–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karpinski M, Rush D, Jeffery J, et al. Flow cytometric crossmatching in primary renal transplant recipients with a negative anti-human globulin enhanced cytotoxicity crossmatch. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(12):2807–2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Bas-Bernardet S, Hourmant M, Valentin N, et al. Identification of the antibodies involved in B-cell crossmatch positivity in renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;75(4):477–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwun J, Burghuber C, Manook M, et al. Successful desensitization with proteasome inhibition and costimulation blockade in sensitized nonhuman primates. Blood Adv. 2017;1:2115–2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim I, Wu G, Chai N-N, Klein AS, Jordan SC. Immunological characterization of de novo and recall alloantibody suppression by CTLA4Ig in a mouse model of allosensitization. Transplant Immunol. 2016;38:84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Upadhyay M, Priya GK, Ramesh P, et al. CD40 signaling drives B lymphocytes into an intermediate memory-like state, poised between naïve and plasma cells. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229:1387–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vincenti F, Rostaing L, Grinyo J, et al. Belatacept and long-term outcomes in kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):333–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim EJ, Kwun J, Gibby AC, et al. Costimulation blockade alters germinal center responses and prevents antibody-mediated rejection. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(1):59–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leibler C, Thiolat A, Henique C, et al. Control of humoral response in renal transplantation by belatacept depends on a direct effect on B cells and impaired T follicular helper-B cell crosstalk. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(3):1049–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pelletier N, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Wong KA, Urich E, Fazilleau N, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Plasma cells negatively regulate the follicular helper T cell program. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(12):1110–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen J, Wang Q, Yin D, Vu V, Sciammas R, Chong AS. Cutting edge: CTLA-4Ig inhibits memory B cell responses and promotes allograft survival in sensitized recipients. J Immunol. 2015;195(9):4069–4073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nair JR, Carlson LM, Koorella C, et al. CD28 expressed on malignant plasma cells induces a prosurvival and immunosuppressive microenvironment. J Immunol. 2011;187(3):1243–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rozanski CH, Utley A, Carlson LM, et al. CD28 promotes plasma cell survival, sustained antibody responses, and BLIMP-1 upregulation through its distal PYAP proline motif. J Immunol. 2015;194(10):4717–4728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neumann B, Klippert A, Raue K, Sopper S, Stahl-Hennig C. Characterization of B and plasma cells in blood, bone marrow, and secondary lymphoid organs of rhesus macaques by multicolor flow cytometry. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;97(1):19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jordan SC, Lorant T, Choi J, et al. IgG endopeptidase in highly sensitized patients undergoing transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):442–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seifert ME, Brennan DC. Cytomegalovirus and anemia: not just for transplant anymore. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(8):1613–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith EP. Hematologic disorders after solid organ transplantation. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010:281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rane S, Nada R, Minz M, Sakhuja V, Joshi K. Spectrum of cytomegalovirus-induced renal pathology in renal allograft recipients. Transplant Proc. 2012;44(3):713–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olsen S, Spencer E, Cockfield S, Marcussen N, Solez K. Endocapillary glomerulitis in the renal allograft. Transplantation. 1995;59(10):1421–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cathro HP, Schmitt TM. Cytomegalovirus glomerulitis in a renal allograft. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(1):188–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Onuigbo M, Haririan A, Ramos E, Klassen D, Wali R, Drachenberg C. Cytomegalovirus-induced glomerular vasculopathy in renal allografts: a report of two cases. Am J Transplant. 2002;2(7):684–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Browne G, Whitworth C, Bellamy C, Ogilvie MM. Acute allograft glomerulopathy associated with CMV viraemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(4):861–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Birk PE, Chavers BM. Does cytomegalovirus cause glomerular injury in renal allograft recipients? J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8(11):1801–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morath C, Becker LE, Leo A, et al. ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation enabled by non-antigen-specific immunoadsorption. Transplantation. 2012;93(8):827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.