Abstract

A regional programme to combat lymphatic filariasis in the Pacific islands is showing great promise as it reaches its halfway point. The Pacific Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis (PacELF), established in 1999, aims to eliminate the disease from the Pacific by 2010 – ten years ahead of the global target. Set up with support from Australia, and now funded primarily by Japan and underpinned by the Word Health Organization, PacELF is providing evidence that Pacific nations can work cooperatively to rid the region of one of its worst scourges, in addition to discovering techniques and new tools that should be of use in other regions.

Elimination of lymphatic filariasis

The Pacific Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis [PacELF (http://www.pacelf.org/)] was established one year before the Global Alliance to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis [GAELF (http://www.filariasis.org)] came into force in 2000. The goal of PacELF is to eliminate the disease by 2010, ten years before the global GAELF target date. Annual mass administration of single-dose antifilarial drug combinations is the strategy recommended by the World Health Organization [WHO (http://www.who.int/en/)] to stop transmission of lymphatic filariasis (LF). Eleven of the first 22 nations to introduce nationwide drug-administration programmes were in the Pacific. PacELF is pioneering the way towards disease elimination, developing and refining the components necessary for success and encouraging other regions around the globe to persevere in their efforts to conquer a disease that threatens 20% of the world population.

PacELF is a collaboration of 22 Pacific nations that covers 3000 islands extending over an area larger than Russia and Europe combined, and serves >8.6 million people. It was set up following a history of successful yet isolated campaigns to control LF in the Pacific, mostly using diethylcarbamazine citrate (DEC) – the first antifilarial drug, which was developed in 1947. In the past, although disease prevalence was markedly diminished, it usually returned to its original levels. Nonetheless, belief was instilled that the disease could be conquered. In 1993, the International Task Force of Disease Eradication reinforced this notion, pronouncing that LF (Box 1) was one of only six diseases that were ‘eradicable or potentially eradicable’ [1]. The subsequent advent of cheap and simple to use diagnostic tools, and better and safer drugs and drug combinations improved mosquito-control measures, and innovative methods for dealing with disease symptoms and physical bodily damage resulting from the disease provided further credence [2]. In 1997, the WHO adopted a resolution to ‘strengthen activities toward eliminating lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem’, requesting that the WHO Director General ‘mobilise support for global and national elimination activities’ [World Health Assembly Resolution 50.29 (http://www.filariasis.org/index.pl?iid=2484)]. Fortunately, the end of the 20th century also witnessed a massive upsurge in resources and donations targeted at fighting diseases of poverty, especially among communities in developing countries and, thus, funds were forthcoming to support large-scale and innovative health interventions.

Box 1. What is LF?

LF is a non-fatal, highly disabling disease that threatens 20% of the world population. The disease, also known as elephantiasis, causes enlargement of the entire leg, arm, genitals or breast, and affects 10–50% of people in the worst-affected communities. Today, 120 000 000 people are infected, 40 000 000 of whom are seriously incapacitated or disfigured, making LF the world's second leading cause of disability. Despite being one of the diseases that cause the most disfigurement, cultural and dress factors help to keep LF hidden and, thus, neglected, although its often-grotesque outward manifestations make the disease one of the most stigmatizing and psychologically traumatizing. The LF-causing parasite Wuchereria bancrofti is transmitted from person to person by the bite of mosquitoes. The parasite lives only in humans, and the absence of an animal source of infection means that elimination should be possible. This is reinforced by the estimation that it takes several thousands, if not tens of thousands, of bites from infective mosquitoes to establish an infection. Once in the human body, the worms mature, with adults lodging in the lymphatic system, which is crucial for maintaining the tissue fluid balance of the body and which has a major role in the immune system. Infection is usually acquired in childhood and, although infected, many individuals never show outward signs of the disease.

Globally, the fight against LF has taken giant steps forward since the beginning of the new millennium, with the number of treatments quickly soaring from 2 million in 2000 to >130 million by the end of 2003. The advances have been both rapid and cost effective. Indeed, some observers recognize that the campaign to eliminate LF – although dependent on a complex partnership that encompasses national commitment, extensive private- and public-sector collaborations and the largesse of a variety of donors – is the most effective pro-poor public-health intervention currently being implemented [3].

The PacELF community

LF is endemic or partially endemic in 16 of the 22 countries that form PacELF (Box 2). In 2005, data showed that 500 000 people were infected in the PacELF community, with a prevalence of 6.5% – well below estimates in 1997 of 1.8 million infected and 29% prevalence [4]. The PacELF islands face unique difficulties. They are generally small, with correspondingly low population numbers. They are scattered across vast expanses of ocean, national health budgets are relatively meagre and household funds to buy medicines are scarce. However, ridding one nation of the disease might not be sufficient because it can swiftly be reintroduced through mosquitoes (especially Aedes spp.) and people using rapid forms of transport. In addition, natural disasters (e.g. cyclones and tsunamis), man-made disruptions (e.g. political upheavals) and other health crises [e.g. severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)] can hinder even the best-planned control programmes. Consequently, there is a pressing need for the countries involved to share resources and work together to eliminate the disease on a regional basis. Experience has shown that large-scale programmes to control vector-borne disease that focus on a single intervention often fail. The likelihood of success increases when a multifaceted strategy is cohesively employed using a variety of tools such as mass drug administration (MDA), vector control, helminth control, health education (especially school based) and home treatment. Fortunately, most of the communities in the Pacific have a deep-rooted respect for altruistic community values, with many living in long-standing and all-pervasive extended-family systems that favour the group above the individual. The PacELF programme reflects these values (Box 3). During the 1990s, the development of a quick and effective diagnostic kit was coupled with the advent of two new drugs – albendazole and ivermectin, which are being donated for as long as needed, free of charge, by GlaxoSmithKline (http://www.gsk.com/index.htm) and Merck (http://www.merck.com/), respectively. The drugs complement DEC (any two drugs given together enhance the effectiveness of any of the drugs administered singly), so changing the focus towards diagnosing, treating and preventing disease at the community rather than the individual level is well suited to Pacific communities [5].

Box 2. The PacELF community.

The 22 PacELF countries and territories are: American Samoa, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, New Caledonia, Niue, Northern Marianas, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Pitcairn Island, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, and Wallis and Futuna.

Box 3. PacELF activities.

Based at the WHO office in Fiji, the overarching aim of PacELF is to interrupt disease transmission through the mass administration of a two-drug combination and to alleviate suffering caused by LF [2]. This is being achieved by

(i) Baseline surveys using ICT kits to assess prevalence of infection.

(ii) Elimination activities in countries that show prevalence of >1% by

-

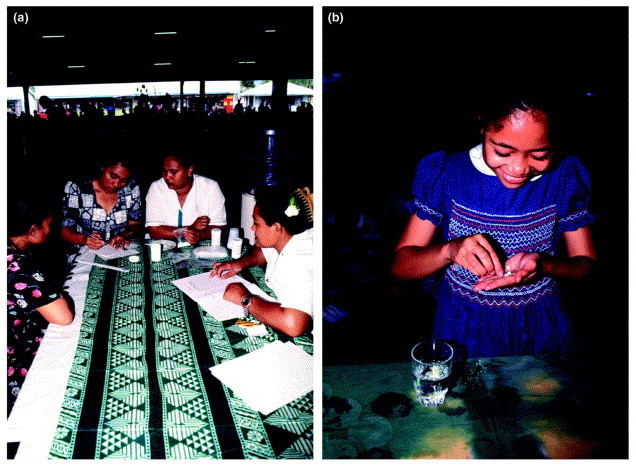

•MDA of DEC and albendazole, once annually for five years to the entire ‘at-risk’ population (Figure I )

Figure I.

The first PacELF MDA (Samoa, 1999). (a) Woman registering and awaiting drugs from health workers at a distribution point that has been set up in the main food market of Apia (the capital of Samoa) to dispense medication to shoppers and passers-by. (b) At a central point in a rural village of Samoa, a young girl prepares to take the DEC and albendazole tablets that have been given to her by a health worker. All eligible island members must take their tablets if the MDA is to be successful. Photo credit in (a) and (b): WHO/TDR/Crump.

The first PacELF MDA (Samoa, 1999). (a) Woman registering and awaiting drugs from health workers at a distribution point that has been set up in the main food market of Apia (the capital of Samoa) to dispense medication to shoppers and passers-by. (b) At a central point in a rural village of Samoa, a young girl prepares to take the DEC and albendazole tablets that have been given to her by a health worker. All eligible island members must take their tablets if the MDA is to be successful. Photo credit in (a) and (b): WHO/TDR/Crump. -

•secondary approaches if prevalence of >1% persists by

-

-selective intensive treatment

-

-reduction in mosquito vector numbers.

-

-

(iii) Alleviation and prevention of suffering from lymphoedema, hydrocoele and other manifestations by

-

•

training affected individuals and their relatives or care-givers (formal and informal) in home-based care technique

-

•

increasing access to surgery for hydrocoele, wherever possible.

PacELF will carry out four surveys in each of the 22 member countries

(i) a baseline study to establish the size of the disease problem (this was completed in all nations by 2002);

(ii) a midterm review will evaluate the impact of the MDA activities (to be completed in all nations by 2006);

(iii) a final survey to determine that drug-distribution programmes have been successful (to be completed by 2008);

(iv) a survey to confirm and certify that disease transmission has been eliminated by 2010.

PacELF operations

The PacELF strategy is to use albendazole in combination with DEC, the efficacy of which has been established. It is known that the combination of DEC (6 mg kg−1) with albendazole (400 mg) eliminates up to 99% of microfilariae for at least 12 months [6]. Consequently, treatment is required only annually. DEC is an effective antifilarial drug that can kill both immature and adult worms and, despite >50 years of widespread use, no resistance to it has been recorded. Albendazole produces few adverse reactions and, in addition to its antifilarial effects, can kill several common intestinal worms (and some protozoan parasites), thus bestowing additional improvements to general health, nutrition and productivity, especially enabling physical and educational improvements in children. Consequently, the added benefits of albendazole encourage communities to comply and take the drug combination. Full compliance is essential; otherwise, a reservoir of parasites will remain in infected individuals and be available for transmission. Although DEC, albendazole and ivermectin have different modes of action, it is known that they suppress microfilariae for >12 months and that adult disease-causing Wuchereria bancrofti worms can reproduce for 4–6 years. Therefore, annual MDA programmes (with all eligible community members complying) must be sustained for at least five years to halt transmission, although this timeframe remains a matter of conjecture. The new easy-to-use, rapid immunochromatographic card diagnostic test (ICT) can identify adult filarial worm antigen within a few minutes using a finger-prick blood sample and, thus, can be used to help assess prevalence, map the disease and measure the impact of MDA programmes.

In Fiji, PacELF coordinates drug procurement, storage and supply, in addition to providing technical advice, health-promotion guidance, surveillance guidelines and data management, and functioning as a liaison among all associated parties. PacELF work is made possible by support from the Japanese government (which provides DEC tablets, diagnostic kits and financial aid), provision of albendazole from GlaxoSmithKline and financial aid from a group of donors, coupled with the resources and goodwill of all governments, health workers and civil society in communities throughout the Pacific.

Progress

In 1999, Samoa became the first country to implement MDA using the new GAELF strategy. This involved organizing the transportation and distribution of DEC and albendazole to all 175 000 eligible Samoans in communities throughout the nine islands of the country, in addition to carrying out earlier baseline surveys, prior awareness-raising and public-health information campaigns, and coordinating comprehensive follow-up surveys to monitor and evaluate the impact. The history of LF in Samoa dates back to the 1920s, when a 1928 survey indicated a prevalence of 36.1%; the first nationwide attempts at control occurred in the 1940s [7]. The first Samoan MDA carried out under PacELF auspices proved to be an intense and difficult operation, and many lessons were learned. For example, the use of and support from churches proved invaluable in fully engaging the national population. In addition, stringent efforts were taken to train infected individuals, their family members and community care-givers to recognize signs of the disease, how best to carry out intense routine washing (with soap and water) and to use antiseptics on affected limbs or swellings, thus avoiding the secondary bacterial and fungal infections that culminate in elephantiasis.

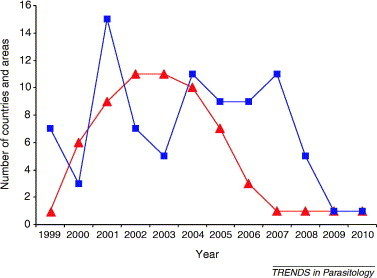

Between 2001 and 2004, PacELF received and orchestrated the use of 212 500 ICT cards, 780 460 000 DEC tablets and 6 492 000 albendazole tablets. Initial results from midterm surveys in five countries show that MDA achieved an average of 70% coverage, and ICT figures show a 40% reduction in prevalence [8]. In Samoa, the full five rounds were completed in 2003 (when MDA covered 80% of the population). According to preliminary results, overall prevalence fell from an initial 4.5% to a 1.1% (as indicated by ICT results) or 0.4% (as confirmed by blood testing for microfilariae) level. Although additional treatments will probably continue in several high-risk and suspect areas, the MDA component of the Samoan programme was successfully concluded. Eleven PacELF countries will have completed five rounds of MDA by 2006, leaving only one country still implementing drug distribution, although the 11 will still be monitoring the impact of their MDA (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Graph showing total numbers of countries and areas implementing MDA, and monitoring and evaluation. Red triangles represent total number of countries and areas implementing MDA, and blue squares represent total number of countries and areas implementing monitoring and evaluation.

Surveys in several nations show dramatic improvements in the understanding of filariasis transmission, diagnosis, treatment and prevention. In Fiji, for example, 82% of the population now recognizes that mosquitoes transmit the disease, compared with only 67% before the start of the PacELF campaign. Moreover, the MDA work improves the efficiency of national health systems, and boosts the standing and capacity of health workers and nurses. Perhaps more importantly, as a result of the PacELF-driven MDA, every individual throughout the Pacific region, irrespective of gender or age, had access to the health service at least once a year.

PacELF challenges

Nevertheless, problems still abound. For example, MDA remains a logistical nightmare, with French Polynesia alone comprising communities on 118 islands and atolls scattered over 5 000 000 km2 of ocean. Moreover, the high efficiency of Aedes polynesiensis mosquitoes as vectors means that even good MDA campaigns might have limited impact unless additional mosquito-control measures are implemented. Evidence from regional malaria-control programmes suggests that residual spraying can interrupt transmission of W. bancrofti, as occurred in the Solomon Islands. Because the aedine mosquito vectors responsible for transmission in many PacELF countries also transmit arboviruses – notably dengue – and, in Papua New Guinea, the anopheline mosquitoes that transmit LF also transmit malaria, mosquito-control measures could have a positive multi-disease impact [9]. Bednet use can also markedly reduce the transmission of both malaria and LF [10]. There is, therefore, a clear need to integrate PacELF activities with other health service interventions and vector-control programmes. It is also proposed that children who regularly attend paediatric clinics or schools be examined for LF infection and that these children be considered to reflect the population as a whole. This would drastically reduce the resources needed for MDA monitoring and evaluation.

Papua New Guinea represents the biggest remaining challenge for PacELF. Of the population of 5 000 000 that is scattered over a mass of 462 000 km2 of the remotest, most inhospitable and inaccessible land in the tropics, filariasis prevalence in some areas is estimated to be 56% [11], although the overall national prevalence is only 6%. Reaching the population with sustained MDA programmes will be a massive undertaking [12]. The necessary level of treatment coverage will require a comprehensive and intense campaign of MDA, health education and communication [13]. Moreover, in other countries such as Kiribati, compliance is still a problem, with less than 50% of the population covered by MDA in both 2002 and 2003. In French Polynesia, MDA is not proving as effective as it should, and a sixth round of MDA has had to be planned. It is also likely that, even after the 2010 elimination date, one or two foci will remain in which tightly targeted drug interventions will be required to complete the elimination. However, the PacELF community does not regard any of these obstacles as insurmountable, and most nations are well on the way to meeting the elimination target date.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Ministries and Departments of Health in the 22 countries that form PacELF for their enthusiasm and cooperation, without which the effort to eliminate LF from the Pacific would not be possible. We also thank the WHO, the Japanese Government and all partners for their financial and technical support of this programme.

References

- 1.CDC Recommendation of the International Task Force for Disease Eradication. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1993;42:1–38. ( http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr4216.pdf) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.PacELF . PacELF Home Office; 2004. PacELF Handbook: Facts and Methods for Lymphatic Filariasis Elimination in the Pacific. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molyneux D. Lymphatic filariasis (elephantiasis) elimination: a public health success and development opportunity. Filaria J. 2003;2:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2883-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michael E., Bundy D.A. Global mapping of lymphatic filariasis. Parasitol. Today. 1997;13:477–480. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)01151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gyapong J.O. Treatment strategies underpinning the global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2005;6:179–200. doi: 10.1517/14656566.6.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ottesen E. The role of albendazole in programmes to eliminate lymphatic filariasis. Parasitol. Today. 1999;15:382–386. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suomela S. Eliminating filariasis: getting the job done in Samoa. WHO in Action. 2000;1:6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.PacELF (2004) 6th Annual Meeting Report, PacELF Home Office, Fiji (http://www.pacelf.org/reports/Annual%20Meeting%20Report%202004.pdf)

- 9.WHO . WHO; 2002. Defining the Roles of Vector Control and Xenomonitoring in the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burkot T. Effects of untreated bednets on the transmission of Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax and Wuchereria bancrofti in Papua New Guinea. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1990;84:773–779. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90073-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melrose W. Prevalence of filarial antigenaemia in Papua New Guinea: results of surveys by the School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, James Cook University, Townsville, Australia. P.N.G. Med. J. 2000;43:161–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bockarie M.J., Kazura J.W. Lymphatic filariasis in Papua New Guinea: prospects for elimination. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. (Berl.) 2003;192:9–14. doi: 10.1007/s00430-002-0153-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burkot T. Progress towards, and challenges for, the elimination of filariasis from Pacific island communities. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2002;96(Suppl. 2):S61–S69. doi: 10.1179/000349802125002419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]