Abstract

Human parainfluenza virus (HPIV) infection as an aetiology of acute viral myocarditis is rare, with only few cases reported in the literature to date. Here we report a case of fulminant HPIV-2 myocarditis in a 47 year-old man with viraemia who was successfully treated with intravenous ribavirin and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). There are currently no recommendations on the treatment of HPIV myocarditis. We are, to our knowledge, the first to report a patient with a documented HPIV-2 viraemia that subsequently cleared after the initiation of antiviral therapy. Although it is difficult to definitively attribute the patient's clinical improvement to ribavirin or IVIG alone, our case does suggest that clinicians may wish to consider initiating ribavirin and IVIG in patients with HPIV myocarditis and persistent viraemia not responding to supportive measures alone.

Keywords: Human parainfluenza virus, Myocarditis, Viraemia, Ribavirin

1. Why this case is important

Acute myocarditis is a complex and challenging diagnosis. The pathogenesis of this disease frequently involves viral infections.1 Amongst the viral causes of acute myocarditis, human parainfluenza virus (HPIV) infection as an aetiology is rare with only four cases reported in the literature.2, 3, 4, 5 Two cases of myocarditis associated with HPIV infection were diagnosed by a rise in paired serology2 and a positive viral culture on throat swab.4 A recent report of HPIV myocarditis demonstrated the presence of HPIV-3 ribonucleic acid (RNA) on nasopharyngeal swab, pericardial fluid and cardiac tissue.3 All of these cases however, were diagnosed retrospectively and the aetiological information did not influence case management. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to report a case of HPIV-2 myocarditis with documented viraemia and clearance of viraemia following treatment with intravenous (IV) ribavirin and immunoglobulin (IVIG).

2. Case description

A 47-year-old previously well man presented to a regional hospital with a 7-day history of dyspnoea, chest pain, and lower limb swelling. He had a dry cough without fever 2 weeks prior to admission. On admission he was afebrile, normotensive but tachycardic and had oxygen saturations of 96% while breathing room air. Physical examination revealed signs consistent with cardiac failure. Full blood count revealed a mild leukocytosis (white cell count 12.4 × 109/L, 73% neutrophils, 20% lymphocytes and 7% monocytes) and thrombocytosis (591 × 109/L). His C-reactive protein was marginally elevated (17.3 mg/L) and procalcitonin level was normal. He was in acute renal failure with an elevated creatinine of 155 mmol/L. The cardiac enzymes, creatine kinase (CK), creatine kinase-MB fraction (CK-MB) and troponin I were all elevated at 847 U/L, 48.8 U/L and 2.22 μg/L, respectively. Transthoracic echography showed a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of only 15% with global hypokinesia. A presumptive diagnosis of viral myocarditis was made.

He deteriorated rapidly and required mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure, along with double inotropes and intra-arterial balloon pump (IABP) to support his cardiogenic shock. He developed worsening renal failure, as well as paroxysmal episodes of atrial fibrillation. Endotracheal tube aspirates were negative for influenza virus A and B, HPIV-1, 2 and 3, adenovirus and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) by immunofluorescence. One week after admission, he deteriorated further and was started on extra-corporal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) before being transferred to our hospital.

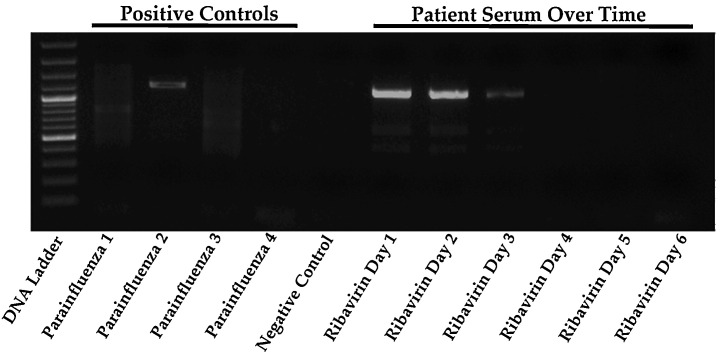

After the transfer, there was still ongoing myocardial inflammation with persistently raised cardiac enzymes. Further tests to elucidate a possible infective aetiology for his myocarditis included negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on serum for parvovirus B19, Epstein–Barr virus, herpes simplex virus and human herpes-6 virus (HHV-6). The human immunodeficiency virus screen, cytomegalovirus IgM, brucella and rickettsial serologies were negative, as was stool for enterovirus by PCR testing. A nasopharyngeal swab sent for respiratory virus multiplex PCR was negative for RSV, influenza A and B, metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, coronavirus and adenovirus. It was however positive for HPIV-2 by both Seeplex Respiratory Viral 12 Detection Assay (Seegene, Rockville) and Luminex xTag Respiratory Viral Panel (Luminex Corporation). Primers specific for HPIV-1, 2 and 3 were then designed by the research laboratory under the Program in Emerging Infectious Disease (PEID) from the Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School using complete genomes of each viral serotype downloaded from GenBank and aligned with MAFFT (a multiple sequence program alignment for amino acid or nucleotide sequences) in Geneious Pro version 5.1.4. Forward and reverse primers sequences were designed to target highly conserved regions and produce amplicons of ∼1–2 kb in length. Primers used were: 5′-GCCTACAGGTGGTGGAG-3′ and 5′-GCTTGATGGTCGTCGGCCG-3′ for HPIV 1, 5′-GCCAGCATCCCACCAGGTGTC-3′ and 5′-GCAGAGCGTATTATTGACCG-3′ for HPIV 2, 5′-GGAGGATATTGATCTCAATG-3′ (HPIV3 F) and 5′-GCAACTAGTGATCTCATTGTACTG-3′ for HPIV 3. The PCR reactions were carried out using Pfu UltraTM polymerase. Utilizing these primer sets, the patient's serum also tested positive for HPIV-2 by PCR indicating an ongoing HPIV-2 viraemia (Fig. 2). Sequencing of the 1062 bp product that sits within the V gene showed 98% similarity with other HPIV-2 sequences deposited in the GenBank (accession number JX889247), confirming the aetiology of myocarditis in our patient. Following detection of HPIV-2, the patient was started on oral ribavirin (loading dose of 10 mg/kg on day 1 and 400 mg three times daily on day 2) but switched to IV ribavirin (10 mg/kg 8 hourly) on day 3 for a total duration of 7 days upon receiving the regulatory approval from the Health Sciences Authority of Singapore. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was given concomitantly at a dose of 0.5 g/kg every other day for 1 week.

Fig. 2.

Serial serum PCRs for HPIV-1–3 and their response to ribavirin therapy. Oral ribavirin was given on days 1 and 2 while IV ribavirin was started from day 3.

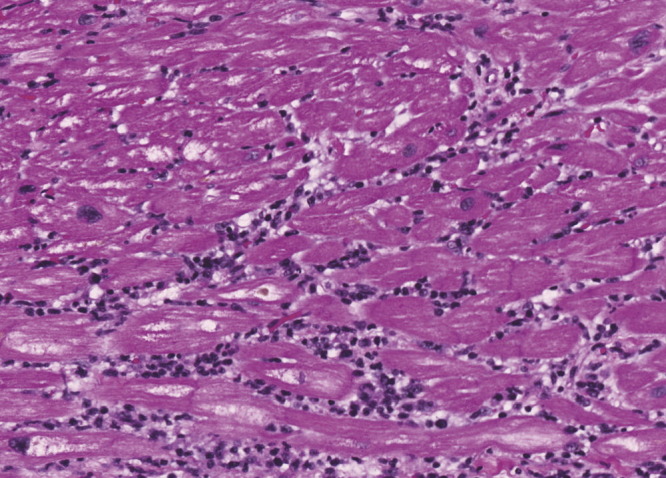

As the patient remained in cardiogenic shock, a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) was implanted the day after IV ribavirin was started, 26 days from initial hospital presentation. Histological examination of the left ventricular apical tissue revealed features in keeping with lymphocytic viral myocarditis (Fig. 1 ), as well as microscopic foci consistent with myocardial ischaemia. There was also coagulation necrosis and other granulating foci showing varying degrees of organization, in keeping with acute, chronic and on-going myocardial ischaemia.

Fig. 1.

Photomicrograph of left ventricular apical specimen showing lymphocytic infiltrate within the myocardium, associated with myocardial fibre damage and necrosis. H and E staining at magnification of 200×.

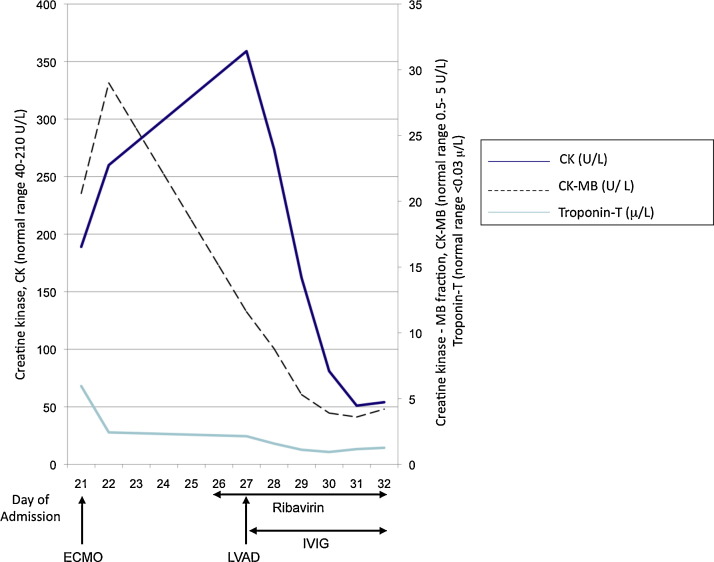

Following IV ribavirin initiation, viraemia clearance was monitored using the PEID RT-PCR assay designed to detect 1062 bp of the HPIV-2 genome and showed a serial decline in HPIV viraemia with clearance on day 4 of ribavirin therapy (Fig. 2 ) along with improvement in myocardial inflammation as reflected by the normalization of the cardiac enzymes (Fig. 3 ). The patient tolerated ribavirin with no evidence of haemolytic anaemia or worsening renal function. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed 2 weeks after ribavirin treatment showed an improvement of the LVEF to 30%. The post-operative recovery was complicated by bleeding that caused a mediastinal haematoma and thrombosis that caused a transient dysphasic stroke. He also suffered from mediastinitis that required a prolonged course of antibiotic and antifungal therapy. After undergoing 6 months of rehabilitation, he recovered his LVEF to 50% and subsequently underwent successful explantation of the LVAD one year after he first presented with myocarditis.

Fig. 3.

Cardiac enzyme changes from time of admission to our hospital in relation to insertion of ECMO, LVAD and initiation of ribavirin and IVIG.

3. Other similar and contrasting cases in the literature

Few reports have demonstrated HPIV as the aetiology of viral myocarditis.2, 3, 4, 5 In most of the previously reported cases (Table 1 ), the diagnosis was made by paired serology. Serology for HPIV however, lacks specificity due to cross reactivity directed against the envelope glycoproteins, HN and F proteins of other paramyxoviruses and hence may be difficult to interpret.7 In others, the diagnosis was established by positive immunofluorescence or culturing the virus from throat swabs.4 One case reported isolating viral RNA from a throat swab as well as endomyocardial tissue using molecular techniques.3 In the current report, we identified HPIV-2 by PCR in the nasopharyngeal swab and serum of a patient with acute myocarditis. Histopathological examination of the cardiac tissue also showed features consistent with a viral myocarditis. We are, to our knowledge, the first to report the successful clearance of HPIV-2 viraemia with ribavirin antiviral therapy.

Table 1.

Summary of previously reported cases of HPIV myocarditis.

| Reference | Age (years) | Method of diagnosis | HPIV serotype | Antiviral treatment | Other management | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Otsu et al., 19785 | 22 | Serology | HPIV-3 | None | Steroids, inotropic support | Survived |

| Wilks et al., 19984 | 37 | Viral culture (throat swab) | HPIV-3 | None | Survived; normal ECG at 3 months | |

| Chen et al., 20062 | 41 | Serology | HPIV-1 | None | Mechanical ventilation, inotropic support | Survived; normal left ventricular function at 6 weeks |

| Romero-Gomez et al., 20113 | 12 | Serology, PCR (cardiac tissue and pericardial fluid) | HPIV-1 and HPIV-3 | Oseltamivir 3 mg/kg twice daily for 5 days (patient's throat swab was positive for influenza A [H1N1] by PCR) | ECMO, heart transplant | Survived |

| Current case | 47 | PCR (blood and nasopharyngeal swab) | HPIV-2 | Ribavirin (oral then IV) and IVIG for 7 days | IABP, ECMO, LVAD | Survived; LVEF 30% at 2 weeks and 50% at 6 months |

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ECG, electrocardiogram; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulins; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

4. Discussion

Myocarditis is a well-recognized sequelae of several viral infections. Coxsackie virus, parvovirus B19, HHV-6 type B and the adenovirus are the most frequent viral etiologies implicated.1, 6 As HPIV myocarditis is a rare and seldom reported entity, it remains unclear if there are any differences in the virulence, presentation and prognosis of each of the four serotypes. Some patients appear to recover spontaneously with only minimal supportive treatment2, 4 while others have required support with ECMO followed by heart transplant.3 Our patient developed cardiac failure requiring inotropic and ECMO support 1 week after developing an influenza-like illness. Although ventricular assist devices are becoming more widely used in patients with cardiac failure of varying etiologies with much success, implanting such a device in patients with viral myocarditis poses technical challenges. The cardiac tissues in these patients are often inflamed and friable, increasing the risk of bleeding and subsequent infection.

Antiviral agents have been evaluated for the treatment of acute myocarditis in animal models and in a few small case series.8, 9, 10 Ribavirin, a synthetic nucleoside, together with interferon alpha improved survival in mice when administered at the time of virus inoculation.8 IVIG has both antiviral and immune modulatory effects and has been used with varying success in patients with acute myocarditis.9, 10 There has, however, not been any case reported on the use of ribavirin or IVIG for the treatment of HPIV myocarditis in humans. Although HPIV viraemia was not tested for at the time of presentation, the presence of persistent myocardial inflammation and the identification of HPIV viraemia 4 weeks into admission suggested ongoing protracted HPIV viraemia. As there are no definitive guidelines on the use of ribavirin or IVIG in HPIV myocarditis, we followed the regime used by Khanna et al. in a case series of haematological patients with RSV respiratory tract infection.11 We demonstrated safety and efficacy for the doses of IV ribavirin (10 mg/kg 8 hourly) and IVIG (0.5 g/kg every other day) used in this case for 7 days. Indeed, the initiation of ribavirin and IVIG in our patient resulted in a prompt resolution of viraemia. There was also improvement in the patient's left ventricular ejection fraction following clearance of viraemia. We do concede, however, that it is difficult to definitively attribute the improvement only to ribavirin or IVIG therapy as there was concomitant placement of the LVAD. Although not tested in our patient, it would have been of interest to check the serological status of the patient in terms of the presence of humoral response to HPIV-2 before IVIG treatment, to ensure that the patient was not suffering from a specific or general form of immunodeficiency.

In summary, we report here a case of HPIV-2 myocarditis with viraemia that responded to antiviral and immune modulatory therapy. As there is no current recommended treatment for acute HPIV myocarditis, clinicians may wish to consider IV ribavirin and IVIG therapy especially in the setting of persistent viraemia not responding to supportive measures alone.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interests

None declared.

Ethics approval

Not required.

References

- 1.Andreoletti L., Leveque N., Boulagnon C., Brasselet C., Fornes P. Viral causes of human myocarditis. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;102:559–568. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen J.J., Lin M.T., Lin L.C., Tseng C.D., Chiang F.T. Myopericarditis associated with parainfluenza virus type 1 infection. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2006;22:163–169. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romero-Gomez M.P., Guereta L., Pareja-Grande J., Martinez-Alarcon J., Casas I., Ruiz-Carrascoso G. Myocarditis caused by human parainfluenza virus in an immunocompetent child initially associated with 2009 influenza (H1N1) virus. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2072–2073. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02638-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilks D., Burns S.M. Myopericarditis associated with parainfluenza virus type 3 infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17:363–365. doi: 10.1007/BF01709464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otsu F., Otake M., Hayakawa H., Toyoda T., Yokota M. A case of parainfluenza viral myocarditis showing various kinds of conduction disturbances. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 1978;67:510–514. doi: 10.2169/naika.67.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuhl U., Paushinger M., Noutsias M., Seeberg B., Bock T., Lassner D. High prevalence of viral genomes and multiple viral infections in the myocardium of adults with “idiopathic” left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 2005;111:887–893. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155616.07901.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Julkunen I. Serological diagnosis of parainfluenza virus infections by enzyme immunoassay with special emphasis on purity of viral antigens. J Med Virol. 1984;14:177–187. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890140212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okada I., Matsumori A., Matoba Y., Tominaga M., Yamada T., Kawai C. Combination treatment with ribavarin and interferon for coxsackie B3 replication. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;120:569–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNamara D.M., Rosenblum W.D., Janosko K.M., Trost M.K., Villanueva F.S., Demetris A.J. Intravenous immune globulin in the therapy of myocarditis and acute cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1997;95:2476–2478. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.11.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNamara D.M., Holubkov R., Starling R.C., Dec G.W., Loh E., Torre-Amione G. Controlled trial of intravenous immune globulin in recent-onset dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2001;103:2254–2259. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.18.2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khanna N., Widmer A.F., Decker M., Steffen I., Halter J., Heim D. Respiratory syncitial virus infection in patients with haematological diseases: single centre study and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:402–412. doi: 10.1086/525263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]