Abstract

The practice of veterinary medicine is facilitated by appropriate equipment, and exotic pet medicine is no exception. Exotic practitioners use standard or modified veterinary and human equipment, and now even enjoy the benefit of specialized products manufactured specifically for exotic pet practice.

Key words: exotic mammal, reptile equipment, endoscope, diagnostics, surgical equipment

In years past, specialized equipment for the practice of exotic animal medicine was nonexistent. Today, equipment is modified from what is available for human or traditional pet medicine, or even manufactured specifically for exotic patients. This has provided the practitioner with tools to greatly improve quality of care and offer services at the same high standard of medicine that were previously only available for dogs and cats.

Diagnostics

Blood sample collection techniques used for exotic mammals and reptiles are modified from traditional pet medicine and utilize a variety of needles, syringes, and other collection devices and containers. Techniques for blood collection are described in detail elsewhere. Most reference laboratories are willing to provide the practitioner with specimen containers designed for smaller volume samples, such as micro-gel separator tubes, both plain and coated with lithium heparin, and smaller calcium or sodium ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid tubes for submission of whole blood. Submitting small volume samples in standard-sized tubes containing anticoagulant may result in dilutional artifact because of improper ratio of anticoagulant to sample (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Blood tubes. Proper handling of blood samples for laboratory submission requires specialized collection tubes. Small separator tubes (third from left) increase the volume of serum or plasma that can be obtained from smaller samples.

Human neonatal- or pediatric-sized culturettes are available from reference laboratories for the collection of culture specimens from locations such as the nasal cavity of rabbits or the ear canal of rodents.

Radiography in very small exotic patients is greatly facilitated by high-speed cassettes and film or mammography film. Techniques for ultrasonography of small exotic mammals and various reptile species have also been described. Ultrasound machines should be equipped with a transducer suitable for the size of the animal, with a small footprint or contact area. Transducers with frequencies from 7.5 to 12 MHz will be the most useful. Many standard ultrasound machines can be fitted with probes of this frequency. Color Doppler is advantageous for assessing blood flow, but it is harder to interpret. Most new ultrasound machines are capable of digital recording to facilitate further review after contact with the patient is completed. Ultrasound-guided biopsy of organs can be performed as in traditional pet species.

Another useful diagnostic modality that has recently received increased attention is diagnostic endoscopy of exotic animals. Rigid endoscopy for determination of sex is well recognized in birds maintained in pet and zoo collections. Recently, more attention has been given to diagnostic endoscopy and the collection of endoscopic-guided samples.1, 2

Diagnostic endoscopy uses rigid endoscopes, most commonly 2.7 and 1.9 mm in diameter. Endoscopes use a high-intensity light source for illumination. The endoscope and light source are the minimum equipment required for visualization of the oral cavity, ear canal, and nasal cavity of small exotic mammals (Fig 2). However, more advanced techniques such as endoscopic evaluation of the urethra, bladder, and vagina, and abdominal or thoracic endoscopy require a diagnostic sheath to allow insufflation of sterile fluid or air to enhance visualization. The diagnostic sheath also allows introduction of a variety of instruments for sample collection for cytology, culture and sensitivity, and/or biopsy.3 All endoscopic procedures benefit from the addition of a camera to allow viewing of images on a monitor, and an image capture system to save images for education, documentation, or teaching purposes. In reptiles, diagnostic endoscopy is most often used to examine the oral cavity, coelomic cavity, vent, urinary tract, and even portions of the reproductive tract of female animals.4, 5

Figure 2.

Endoscopes. Rigid endoscopes (2.7 and 1.9 mm) are the most versatile for use in small exotic mammals and reptiles.

Collection of diagnostic samples is only half the challenge of obtaining meaningful data. Samples must be submitted to laboratories that are familiar with the process and have some degree of expertise in the evaluation of exotic animal specimens. Many veterinary diagnostic laboratories are willing to accept these samples, and a number of facilities actively develop unique tests specifically for exotic animals (for example, tests for viral or bacterial pathogens). A few facilities are even dedicated solely to exotic animal testing.6 See Table 1 for a list of some laboratories offering specialized tests specifically for exotic animals.

Table 1.

Selected Novel Diagnostic Tests Available for the Exotic Mammal Practitioner

| Test | Laboratory | Contact information | Sample required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillosis Ag-Ab whole blood PCR | University of Miami, Comparative Pathology Laboratory | 1-800-596-7390 | Serum Whole blood |

| Baylisascaris procyonis serology Selected primates only | Purdue University, Parasitology Laboratory | 1-765-494-7556 | Serum; offered for selected primates only |

| Bordetella avium PCR | Veterinary Molecular Diagnostics | 1-513-576-1808 | Respiratory secretions |

| Canine distemper (ferrets) PCR | Michigan State University, Diagnostic Center for Population and Animal Health | 1-517-353-2296 | Whole blood Lymphoid tissue Nerve tissue |

| Coronavirus (ECE) PCR | Michigan State University, Diagnostic Center for Population and Animal Health | 1-517-353-2296 | Feces GI biopsy specimens |

| Ferret endocrine panel Ferret insulin levels | University of Tennessee, Clinical Endocrinology Service | 1-865-974-5638 | Serum or plasma |

| Helicobacter sp PCR | Research Associated Laboratory | 1-972-960-2221 | Gastric, colonic swabs |

| Mycobacterium sp PCR | Veterinary Molecular Diagnostics | 1-513-576-1808 | Feces, vent swab, target organ |

| Mycobacterium sp PCR Culture and sensitivity HPLC chromatography | National Jewish Medical and Research Center, Denver, CO | www.njc.org Download acquisition form from reference laboratory link. 1-303-398-1339 | Consult lab for submission instructions |

| Mycobacterium sp PCR Culture | Washington State University, Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory | 1-509-335-9696 | Feces, target tissue |

| Mycobacterium sp PCR | Dr. David Phalen, Texas A&M University | dphalen@cvm.tamu.edu | Fresh frozen tissues |

| Mycoplasma serology Rat respiratory pathogens Multiple rabbit and rodent pathogens: E. Cuniculi Pasteurella multocida | Taconic Anmed | 1-301-762-0366 | Serum |

| Mycoplasma gallisepticum (poultry) PCR | Veterinary Molecular Diagnostic | 1-513-576-1808 | Respiratory swabs |

| Pasteurella sp PCR | Taconic Anmed | 1-301-762-0366 | Tracheal wash, nasal swabs |

| Rotavirus of ferrets PCR | Michigan State University, Diagnostic Center for Population and Animal Health | 1-517-353-2296 | Feces, intestinal biopsy specimens |

| Salmonella sp PCR | University of Georgia, Infectious Diseases Laboratory | 1-706-542-8092 | Fecal or tissue swab |

| Sarcocystis serology | University of Miami, Comparative Pathology Laboratory | 1-800-596-7390 | Serum |

| Urolith analysis (no charge) | University of Minnesota, Urolith Center | 1-612-625-4221 | Urolith |

| West Nile Virus PCR | Veterinary Molecular Diagnostics | 1-513-576-1808 | Whole blood |

Reprinted with permission from Exotic DVM 7(4) 2005.

Ag-Ab = antigen antibody, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, ECE = epizootic catarrhal enteritis, GI = gastrointestinal, HPLC = high-performance liquid chromatography.

Anesthesia and Surgery

Injectable anesthetic protocols require no specialized equipment other than small syringes and needles, and the ability to perform dilutions of drugs for use in very small patients.

Induction and maintenance of gas anesthesia are facilitated by modified or specialized equipment. Several manufacturers make smaller, inhalant anesthetic cones and endotracheal tubes with narrow interior diameters (for example, 1.5 mm). In exotic mammal medicine, intubation of rabbits, ferrets, and larger exotic pets is common. Laryngoscopes with straight Miller blades sizes 0 or 1 facilitate intubation and visualization, particularly in small carnivores. Intubation of smaller mammals is technically much more challenging than that for the larger exotic species previously mentioned. Endoscopically guided intubation may be useful in these difficult cases. Johnson recently described this technique in rabbits, ferrets, prairie dogs, chinchillas, and guinea pigs using a semirigid 1.9-mm endoscope (Focuscope; MDS Inc., Brandon FL USA).7 This may be exceedingly more difficult to impossible to perform in chinchillas and guinea pigs using a true rigid endoscope that is incapable of making the slight bend required to direct the endoscope and tube into the trachea. Other equipment that may aid intubation includes a variety of mouth gags, one designed specifically for ferrets (Nazzy Ferret Mouth Gag; USI/BSI, Universal Surgical Instruments, Glen Cove, NY USA).

Maintenance of core body heat during surgery is critical, especially in smaller exotic patients. Warm water-circulating heating pads, radiant heat bulbs, and forced-air heating systems have all been used successfully in exotic pet practice.

Some small animal ventilators can be used to control depth and frequency of respirations in small exotic mammals.8 Use of the ventilator necessitates proper intubation (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

Ventilator. This small animal ventilator is extremely useful in intubated, very small exotic patients.

Careful and attentive monitoring of anesthetized exotic patients is critical, and no monitoring device or equipment is more important than a dedicated veterinary anesthetist. Clear, transparent drapes allow one to view smaller patients to monitor respiratory rate, depth, and other important parameters. Monitoring devices used regularly in exotic pet medicine include vascular Doppler, a flexible, constant readout temperature probe, electrocardiogram, pulse oximetry, and indirect measurement of blood pressure in larger patients (Figure 4, Figure 5). Recently, techniques have been developed for measurement of blood pressure with a cardiac Doppler and small blood pressure cuffs in patients weighing less than 1 kg.9

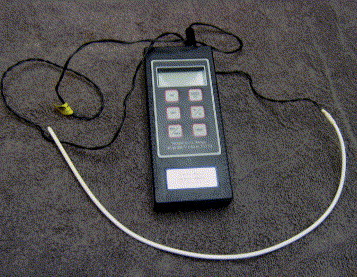

Figure 4.

Anesthetized, intubated rabbit being prepared for surgery. Note the placement of the flexible temperature probe and the Doppler.

Figure 5.

Temperature probe (Veterinary Specialty Products, Mission, KS). A flexible, constant readout temperature probe can be used in all but the smallest patients. Measurement of core body temperature in reptiles is accomplished with esophageal placement of the probe.

Standard aseptic technique is critical in exotic mammal and reptile surgery, despite the fact that surgical site preparation is often more difficult. Less-than-optimal preparation carries the same risk of infection and wound dehiscence found in traditional pet surgery. Clipping of fur from delicate skin must be done carefully to avoid iatrogenic skin lacerations. Small clippers with fine blades are appropriate for these cases. Skin is prepared with warmed dilute (0.05%) chlorhexidine solution followed by warm saline solution rinse, because cold scrub solutions and alcohol can produce hypothermia in small patients.10

A number of materials can be used as sterile drapes in these patients. However, most exotic animal surgeons and anesthetists prefer transparent drapes for reasons described above. Some transparent drapes are self-adhering or can be secured to the patient with smaller, less traumatic towel clamps.

Many of the surgical instruments used in small mammal and reptile surgery are actually human pediatric, vascular, or ophthalmic instruments (Fig 6). A number of manufacturers and distributors market these directly to exotic animal veterinarians. Standard instruments are adequate when working with larger exotic pets, but fine, delicate instruments are essential when considering procedures such as laparotomy in rodents or small reptiles. An example of a typical small exotic mammal/reptile surgical pack is described in Table 2. Radiosurgery has been described for use in exotic mammals and reptiles, and is an effective method for initial incision and for intraoperative hemostasis (Surgitron; Ellman International, Oceanside, NY USA). Wire-tip electrodes are ideal for making incisions, and ball electrodes are useful for coagulation. Bipolar forceps are especially useful for the coagulation of individual vessels.10

Figure 6.

Microsurgical tools. Photo courtesy of V. Capello.

Table 2.

Instruments for a Basic Small Mammal/Reptile Surgical Pack

| 6 Jones towel clamps (small) |

| 1 Adson dressing forceps 4-3/4” |

| 1 Adson tissue forceps 4-3/4” |

| 1 Bard-Parker scalpel blade handle #3 |

| 1 blunt, straight tenotomy scissors 4-1/4” |

| 1 curved LaGrange scissors 4-1/4” |

| 2 Hartman straight mosquito forceps 3-3/4” |

| 2 Hartman curved mosquito forceps 3-3/4” |

| 1 Olsen-Hegar needle holder 5-1/2” |

| Lonestar Retractor |

Access to the surgical field makes these surgeries extremely challenging. A number of specialized retractors allow adequate access. The most versatile retractor is a plastic ring device with a number of completely adjustable stay hooks that can be arranged in any number of useful configurations (Lonestar Retractor; Lonestar Medical Products, Stafford, TX USA) (Fig 7).

Figure 7.

Lonestar Retractor in ferret abdominal surgery. The Lonestar Retractor is extremely useful to improve access and visibility in small exotic mammal and reptile surgeries. Photo courtesy of V. Capello.

Magnification is often of critical importance in smaller patients. A variety of surgical loops, telescopes, and operating microscopes are available. In most cases, magnification of 1.5 to 3.5× is adequate. Magnification allows greater visibility of tiny vessels and other structures, but surgeons must practice regularly and become accustomed to this ocular aid to maximize the benefits. Care must be taken to use a magnification system that allows the surgeon to maintain a normal, comfortable posture, and not be forced to lean over or significantly bend the neck. Improper posture leads to fatigue, thereby contributing to back and neck pain.10, 11

Hemostasis during surgery is of extreme importance in smaller patients because of overall decreased blood volume. Blood losses acceptable in larger species are rapidly fatal in small exotic patients. Sterile, cotton-tipped applicators are useful for application of direct pressure. Radiosurgical hemostasis is mentioned above. Metal hemostatic clips are manufactured in a variety of sizes and are extremely useful in these patients, especially in situations where manipulation of suture material is extremely difficult to impossible (Hemoclip; Weck, Triangle Park, NC USA) (Figure 8, Figure 9). Other useful hemostatic aids include sterile, absorbable gelatin sponge or cellulose products (Gelfoam; Pharmacia and Upjohn Co, Kalamazoo MI USA; Surgicel; Ethicon, Inc., Johnson and Johnson, Somerville, NJ USA). These hemostatic aids are especially useful for situations in which the exact source of mild hemorrhage cannot be identified and directly ligated.

Figure 8.

Small hemoclips and applicator. Small and medium hemostatic clips are the most useful sizes for small exotic animal surgeries.

Figure 9.

Use of hemoclips in rat castration surgery. Hemostatic clips can decrease surgical time in small exotic patients when compared with use of suture. Note the use of a clear surgical drape to allow the anesthetist a better view of the patient.

Recently, a vessel heat-sealing device has been described for use in small exotic patients. The Ligasure vessel-sealing system has been used for vessel ligation and procedures such as castration and hysterectomy in a variety of species, including lizards and chinchillas (Ligasure; Tyco Health Care Valleylab, Boulder, CO USA). The hand-held hemostat comes in a variety of sizes useful for smaller patients. The device can be used via a diagnostic port for endoscopic surgeries, but is currently too large for traditional small exotic endoscopy equipment. Smaller instruments of this type are currently under development.12

Closure of surgical sites follows principles similar to those described for traditional pets. An important exception is the closure of skin in reptile patients. Skin is the holding layer in reptile coelomic surgeries and must be closed with an everting pattern.

Most closures are made with 3-to-0-sized to 8-to-0-sized suture material. Catgut suture material has been found to produce marked inflammatory responses in most species, including reptiles. Although surgeon preference often drives selection of suture material, choices typically include monofilament absorbable materials such as polyglyconate.10 Suture material must be swaged on to small, less traumatic needles to reduce trauma and excessive movement of small exotic patients.

Postsurgical suture disruption is more common in some rodent species, whereas rabbits, ferrets, and guinea pigs tend to be more tolerant of external sutures. For this reason, many surgeons prefer subcuticular closure of skin, followed by tissue adhesive.

References

- 1.Murray M.J. Application of rigid endoscopy in small exotic mammals. Exotic DVM. 2000;2:13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernandez-Divers S.J. Modern endoscopy equipment and advanced endoscopy techniques in birds and reptiles. Exotic DVM. 2003;5:61–64. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lennox A.M. Endoscopy of the distal urogenital tract as an aid in differentiating causes of urogenital bleeding in small mammals. Exotic DVM. 2005;7:43–47. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stahl S.J. Reptile cloacoscopy. Exotic DVM. 2003;5:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez-Divers S.J. Endoscopic evaluation of turtles, tortoises and terrapins. Exotic DVM. 2003;5:88–90. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lennox A.M. Novel diagnostics. Exotic DVM. 2005;7:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson D. Over the endoscope endotracheal intubation of small exotic mammals. Exotic DVM. 2005;7:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernandez-Divers S.J. New small animal ventilator. Exotic DVM. 2001;3:18. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lichtenberger M. Shock, fluid therapy, anesthesia and analgesia in the ferret. Exotic DVM. 2005;7:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett R.A. Preparation and equipment useful for surgery in small exotic pets. Vet Clin North Am (Exotic Anim Pract) 2000;3:563–585. doi: 10.1016/s1094-9194(17)30063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray M.J. Ergonomics in avian and exotic practice. Exotic DVM. 2001;3:11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanford M. Use of a blood vessel sealing instrument in exotic animal surgeries. Exotic DVM. 2005;7:13–17. [Google Scholar]