Highlights

-

•

22.5% of adult patients with H1N1 developed bacterial co-infection.

-

•

Staphylococcus aureus was the most common cause of co-infection.

-

•

Bacterial and viral co-infections were associated with death in bivariate.

-

•

Patients with a bacterial co-infection had greater use of resources.

Keywords: Severe influenza, Influenza A (H1N1) pdm09, Co-infection, Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA, ICU

Abstract

Background

Influenza acts synergistically with bacterial co-pathogens. Few studies have described co-infection in a large cohort with severe influenza infection.

Objectives

To describe the spectrum and clinical impact of co-infections.

Study design

Retrospective cohort study of patients with severe influenza infection from September 2013 through April 2014 in intensive care units at 33 U.S. hospitals comparing characteristics of cases with and without co-infection in bivariable and multivariable analysis.

Results

Of 507 adult and pediatric patients, 114 (22.5%) developed bacterial co-infection and 23 (4.5%) developed viral co-infection. Staphylococcus aureus was the most common cause of co-infection, isolated in 47 (9.3%) patients. Characteristics independently associated with the development of bacterial co-infection of adult patients in a logistic regression model included the absence of cardiovascular disease (OR 0.41 [0.23–0.73], p = 0.003), leukocytosis (>11 K/μl, OR 3.7 [2.2–6.2], p < 0.001; reference: normal WBC 3.5–11 K/μl) at ICU admission and a higher ICU admission SOFA score (for each increase by 1 in SOFA score, OR 1.1 [1.0–1.2], p = 0.001). Bacterial co-infections (OR 2.2 [1.4–3.6], p = 0.001) and viral co-infections (OR 3.1 [1.3–7.4], p = 0.010) were both associated with death in bivariable analysis. Patients with a bacterial co-infection had a longer hospital stay, a longer ICU stay and were likely to have had a greater delay in the initiation of antiviral administration than patients without co-infection (p < 0.05) in bivariable analysis.

Conclusions

Bacterial co-infections were common, resulted in delay of antiviral therapy and were associated with increased resource allocation and higher mortality.

1. Background

Influenza results in significant morbidity and mortality in the U.S and worldwide [1], and this is exacerbated by bacterial co-infections during both seasonal and pandemic influenza years [2], [3], [4]. During the most severe influenza pandemic recorded, in 1918–1919, when an estimated 675,000 people died in the United States [5], [6], epidemiologic, clinical and pathologic data indicate that the majority of influenza patients died from bacterial pneumonia rather than from the influenza virus itself. Bacterial co-infections should thus be studied in order to devise effective preventative and therapeutic strategies [2], [3], [7].

Influenza virus has been shown to have complex effects on the human lung, priming the respiratory tract for synergistic pathogenesis with a bacterial co-infection [8]. Morbidity and mortality are increased when bacterial pneumonia complicates influenza infection as compared with bacterial pneumonia in the absence of influenza infection [9], [10].

During the 1918 and 1968–1969 pandemics, Streptococcus pneumoniae was likely the most common co-pathogen [3], [11]. In the 1957–1958 pandemic, many reports identified Staphylococcus aureus as the most frequently cultured co-pathogen [3], [12], [13]. More recently S. aureus has been increasingly found in cases of fulminant pneumonia complicating influenza infection [14], [15]. Haemophilus influenzae, with the introduction of the H. influenzae type B conjugate vaccine in 1985 [16], and Streptococcus pyogenes have decreased in prevalence over time [17]. Vaccination, novel antibiotics, and probably more importantly, viral or bacterial strain-related differences account for shifts in etiology of the most common bacterial co-infections [8].

A novel pandemic influenza A strain, influenza A (H1N1) pdm09, emerged in 2009. Reported rates of bacterial co-infection among severely ill patients varied between 17.5% and 25% for community-acquired influenza patients in the 2009–2010 season [18], [19] and 33% in a study of combined community-acquired and hospital-acquired influenza patients [20]. In these and other studies the most common community-acquired pathogens included S. pneumoniae and then S. aureus [10]. The risk of co-infection and spectrum of bacterial species has not been studied during the 2013–2014 season, the first postpandemic year in which influenza A (H1N1) pdm was the predominant circulating influenza strain.

2. Objectives

We recently completed a retrospective study of 507 patients with severe influenza treated in intensive care units (ICUs) of 33 U.S. hospitals during the 2013–2014 influenza season [21]. The objectives of the present study were to evaluate bacterial and viral co-infection in this cohort, to describe the spectrum of co-infections and to determine their clinical impact.

3. Study design

We performed a retrospective cohort study of all patients with laboratory confirmed influenza A and/or influenza B infection who were diagnosed with influenza during an ICU stay or within 30 days prior to an ICU admission between September 1, 2013 and April 1, 2014 at 33 U.S. study sites that made up the Severe H1N1 Influenza Consortium (SHIC) [21]. Laboratory testing may have been with a PCR-based test, a rapid test or viral culture. Complete laboratory data were accessed from infection control records, an enterprise data warehouse or directly from the clinical microbiology laboratory. Institutional review boards approved the study at each of the participating sites.

3.1. Data collected

Data for this study were abstracted by a physician from each center’s electronic health record (EHR) and entered into a REDCap database [22]. Data abstracted and study site information were previously described [21].

Bacterial co-infection was defined in patients having one or more isolates obtained from a blood culture and/or a pleural fluid, sputum, tracheal or bronchoscopic sample if the isolate was a pathogen thought to be causing a true infection in the opinion of the treating physician and if the isolate was collected within 30 days of ICU admission or present on arrival to the ICU. Viral co-infection was defined in patients having a positive PCR or appropriate antibody test for a viral pathogen other than influenza. Bacterial co-infections cultured within 48 h of hospital admission were defined as community-acquired; those cultured after 48 h were considered to be hospital-acquired. Bacterial identification and susceptibility testing were performed by methods determined by institutional guidelines. For all patients, management was according to institutional practices.

3.2. Statistical analysis

STATA v12 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LP) was used for all analyses. Outliers were reexamined in the EHR to ensure data accuracy. No subject with outlying values was excluded from any analysis. Descriptive statistics were tabulated. Bivariable analyses were used to compare potential risk factors for bacterial co-infection diagnosed during the 30 days after ICU admission or present on admission. A multivariable logistic regression model was developed to determine which of the variables significantly associated in bivariable analyses (p < 0.05) were independently associated with co-infection. Further multivariable analysis was used to predict risk of death among co-infected patients and also to assess resource utilization accounting for admission SOFA score.

4. Results

Five hundred and seven patients with severe influenza were admitted to ICUs at one of the 33 U.S. hospitals participating in the SHIC study in 2013–2014. In this cohort influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 caused 311 (61.3%) infections, and influenza A virus that were not subtyped caused 170 (33.5%) additional infections. Other influenza strains caused 5.2% of infections (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 507 patients with severe influenza infection in the U.S. diagnosed between September 1, 2013 and April 1, 2014, comparing adult and pediatric patients.

| Characteristicsa | Adults (N = 444) No. (%) | Children (N = 63) No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 223 (50.2) | 28 (44.4) |

| Age group | 0–4 yr | – | 39 (61.9) |

| 5–9 yr | – | 10 (2.0) | |

| 10–17 yr | – | 14 (2.8) | |

| 18–49 yr | 156 (30.8) | – | |

| 50–64 yr | 185 (36.5) | – | |

| ≥65 yr | 103 (20.3) | – | |

| Influenza type and subtype | A—H1N1 pdm2009 | 274 (61.7) | 37 (58.7) |

| A—subtype not specified | 150 (33.8) | 20 (31.7) | |

| A—H1 subtype not pdm2009 | 6 (1.4) | 2 (3.2) | |

| A—H3 | 3 (0.7) | 2 (3.2) | |

| B | 11 (2.5) | 2 (3.2) | |

| Initial influenza diagnostic test (N = 506) | Polymerase chain reaction | 369 (83.1) | 38/62 (61.3) |

| Rapid influenza test | 61 (13.7) | 18/62 (29.0) | |

| Viral culture | 7 (1.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 7 (1.6) | 6/62 (9.7) | |

| Influenza vaccine | Received 2013–14 vaccine (N = 258) | 108/210 (51.4) | 18/48 (37.5) |

| Respiratory bacterial co-infection | Infection at any point during hospitalization | 103 (23.2) | 11 (17.5) |

| Infection cultured within 48 h of hospital admission | 56 (12.6) | 6 (9.5) | |

| Infection cultured greater than 48 h after hospital admission | 47 (10.6) | 5 (7.9) | |

| Respiratory viral co-infection | Infection at any point during hospitalization | 13 (2.9) | 10 (15.9) |

| Antibacterials | Received antibiotics | 418 (94.1) | 49 (77.8) |

| Placed on empiric Community-Acquired Pneumonia therapyb | 146 (32.9) | 10 (15.9) | |

| Placed on empiric Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia therapyc | 219 (49.3) | 9 (14.3) | |

| Antivirals | Received after symptom onset | 421 (94.8) | 57 (90.5) |

| Initiated ≤48 h after symptom onset (N = 474) | 110/417 (26.4) | 32/57 (56.1) | |

| Died | 93 (20.9) | 4 (6.4) | |

When there are missing data for a specific variable, the n for subjects with data on this variable is indicated in the far left column.

Defined as either a respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin or moxifloxacin) or a combination of a broad-spectrum beta-lactam drug (ceftriaxone, cefepime, ampicillin-sulbactam, piperacillin-tazobactam, carbapenems) and azithromycin.

Defined as combination therapy targeting methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA), which includes vancomycin or linezolid, and a second agent targeting Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which includes piperacillin-tazobactam, ceftazidime, cefepime, carbapenems (with the exception of ertapenem), aztreonam, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin and colistin.

There were 444 adult and 63 pediatric subjects. Baseline characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Bacterial co-infection was present in 114 (22.5%) subjects, comprising 23.2% of adult and 17.5% of pediatric subjects. Sixty two (12.2%) subjects developed community-acquired bacterial co-infection and 52 (10.3%) subjects developed hospital-acquired bacterial co-infection. Of the patients who developed community-acquired and hospital-acquired bacterial co-infections, 15/62 (24.2%) and 14/52 (26.9%), respectively, had no significant comorbid conditions.

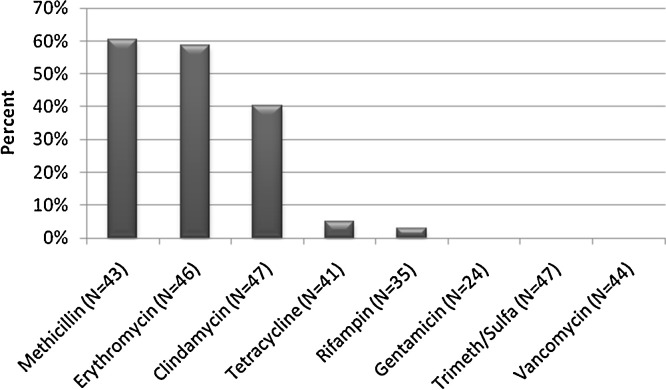

There were 129 total bacterial isolates cultured from the 507 patients in our cohort (Table 2 ), including 26 (20.2%) methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA), 21 (16.3%) methicillin susceptible S. aureus (MSSA), 20 (15.5%) Enterobacteriaceae species, 18 (14.0%) Pseudomonas species, 7 (5.4%) S. pneumoniae and 37 (28.7%) other species (Table 2). S. aureus susceptibilities are displayed in Fig. 1 . Of the MRSA isolates, all were susceptible to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 96.2% to tetracycline, 56% to clindamycin and 20.8% to erythromycin.

Table 2.

Bacterial co-pathogens among 507 patients with severe influenza infection in the U.S. diagnosed between September 1, 2013 and April 1, 2014 by source of isolate.

| Bacterial co-pathogen | Frequency; N (%) | Blood isolates; N (%) | Sputum isolates; N (%) | Blood and Sputum isolates; N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus | 26 (20.2) | 3 (11.5) | 18 (69.2) | 5 (19.2) |

| Methicillin susceptible Staphylococcus aureus | 21 (16.3) | 3 (14.3) | 17 (81.0) | 1 (4.8) |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 20 (15.5) | 2 (10.0) | 17 (85.0) | 1 (5.0) |

| Pseudomonas sp. | 18 (14.0) | 2 (11.1) | 16 (88.9) | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 7 (5.4) | 4 (57.1) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (14.3) |

| Enterococcus sp. | 5 (3.9) | 5 (100) | ||

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 4 (3.1) | 4 (100) | ||

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 4 (3.1) | 4 (100) | ||

| Viridans streptococci | 4 (3.1) | 4 (100) | ||

| Haemophilus influenzae | 3 (2.3) | 3 (100) | ||

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 3 (2.3) | 3 (100) | ||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 3 (2.3) | 3 (100) | ||

| β-hemolytic streptococci (Not Group A or B) | 2 (1.6) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | |

| Burkholderia sp. | 2 (1.6) | 2 (100) | ||

| Corynebacterium sp. | 2 (1.6) | 2 (100) | ||

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 2 (1.6) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | |

| Bordetella bronchiseptica | 1 (0.8) | 1 (100) | ||

| Sphingomonas paucimobilis | 1 (0.8) | 1 (100) | ||

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 1 (0.8) | 1 (100) |

Specific bacterial species not listed include Escherichia coli (N = 7), Enterobacter cloacae (N = 3), Klebsiella pneumoniae (N = 5), Klebsiella oxytoca (N = 1), Serratia marcescens (N = 1), Citrobacter freundii (N = 1), Enterobacter gergoviae (N = 1), Proteus mirabilis (N = 1), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (N = 17), Pseudomonas fluorescens (N = 1), Enterococcus faecium (N = 3), Enterococcus faecalis (N = 2), Streptococcus mitis (N = 2), Streptococcus parasanguinis (N = 1), Streptococcus salivarius (N = 1), Staphylococcus epidermidis (N = 3) and Corynebacterium striatum (N = 1).

Fig. 1.

Antibiogram of Staphylococcus aureus isolates (n = 47) from co-infections, showing the percent that were resistant or intermediate to selected antibacterial drugs from 47 patients with severe influenza in the U.S. between September 1, 2013 and April 1, 2014.

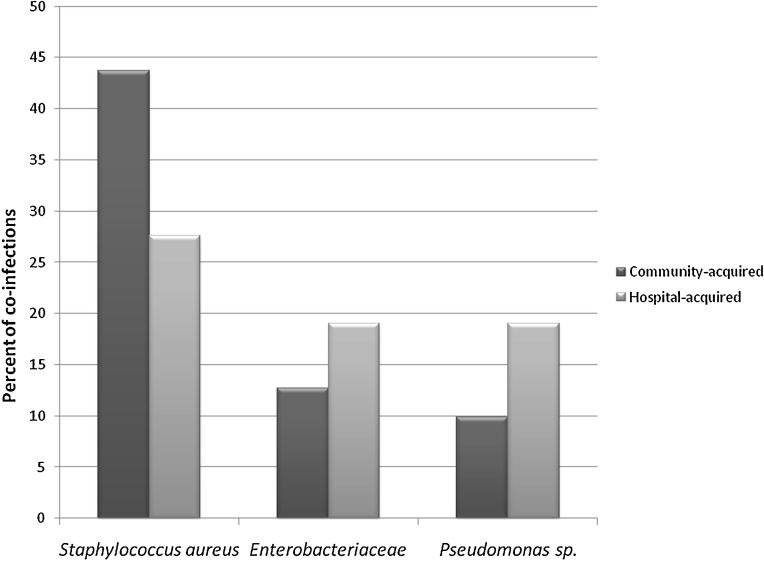

S. aureus was the most prevalent species among both community- (43.7%) and hospital-acquired (27.6%) pathogens (Table 3 and Fig. 2 ). The prevalence of S. aureus was lower among hospital-acquired co-infections as compared with community-acquired co-infections. In contrast, the prevalence of Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas sp. was higher among hospital-acquired bacterial co-infections (19.0% and 19.0%, respectively) as compared to community-acquired bacterial co-infections (12.7% and 9.9%, respectively). S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae and S. pyogenes were not isolated among hospital-acquired pathogens but were present among community-acquired co-infections (9.9%, 4.2%, and 2.8%), respectively.

Table 3.

Bacterial co-pathogens among 507 adult and pediatric patients with severe influenza infection in the U.S. diagnosed between September 1, 2013 and April 1, 2014 by site at acquisition (community or hospital acquired) and presence or absence of respiratory comorbidities.

| Age Group | Co-Pathogen | Community acquired |

Hospital acquired |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of respiratory comorbidities; N (%) | Absence of respiratory comorbidities; N (%) | Presence of respiratory comorbidities; N (%) | Absence of respiratory comorbidities; N (%) | ||

| Adults (N = 117) | Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus | 5/28 (17.8) | 11/38 (28.9) | 3/23 (13.0) | 5/28 (17.9) |

| Methicillin susceptible Staphylococcus aureus | 6/28 (21.4) | 6/38 (15.8) | 2/23 (8.7) | 4/28 (14.3) | |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 5/28 (17.9) | 4/38 (10.5) | 5/23 (21.7) | 5/28 (17.9) | |

| Pseudomonas sp. | 4/28 (14.3) | 3/38 (7.9) | 6/23 (26.1) | 3/28 (10.7) | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 5/38 (13.2) | ||||

| Enterococcus sp. | 1/38 (2.6) | 1/23 (4.3) | 2/28 (7.1) | ||

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 1/38 (2.6) | 1/23 (4.3) | 2/28 (7.1) | ||

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 2/28 (7.1) | 1/38 (2.6) | |||

| Viridans streptococci | 1/38 (2.6) | 2/23 (8.7) | 1/28 (3.6) | ||

| Haemophilus influenzae | 2/28 (7.1) | 1/38 (2.6) | |||

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 1/28 (3.6) | 2/28 (7.1) | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 3/23 (13.0) | ||||

| β-hemolytic streptococci (Not Group A or B) | 2/38 (5.3) | ||||

| Burkholderia sp. | 2/28 (7.1) | ||||

| Corynebacterium sp. | 1/28 (3.6) | 1/38 (2.6) | |||

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 1/28 (3.6) | 1/38 (2.6) | |||

| Bordetella bronchiseptica | 1/28 (3.6) | ||||

| Sphingomonas paucimobilis | 1/28 (3.6) | ||||

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 1/28 (3.6) | ||||

| Children (N = 12) | Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus | 1/4 (25.0) | 1/6 (16.7) | ||

| Methicillin susceptible Staphylococcus aureus | 1/1 (100.0) | 1/4 (25.0) | 1/6 (16.7) | ||

| Enterobacteriaceae | 1/6 (16.7) | ||||

| Pseudomonas sp. | 1/1 (100.0) | 1/6 (16.7) | |||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 2/4 (50.0) | ||||

| Enterococcus sp. | 1/6 (16.7) | ||||

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 1/6 (16.7) | ||||

Fig. 2.

Percentage of community-acquired and hospital-acquired co-infections attributed to Staphylococcus aureus, Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas sp. among 507 patients with severe influenza in the U.S. between September 1, 2013 and April 1, 2014.

Patient characteristics associated with development of bacterial co-infection among adults (>17 years of age) in bivariable analyses are shown in Table 4 . The number of children in our cohort who developed a bacterial co-infection was too small to assess for risk factors for co-infection. Characteristics independently associated with the development of bacterial co-infection in adults included absence of cardiovascular disease (OR 0.41 [0.23–0.73], p = 0.003), leukocytosis at ICU admission (>11 K/μl, OR 3.7 [2.2–6.2], p < 0.001; reference: normal WBC 3.5–11 K/μl) and elevated SOFA score at ICU admission (for each increase by 1 in SOFA score, OR 1.1 [1.0–1.2], p = 0.001).

Table 4.

Patient characteristics associated with bacterial co-infection among 444 adult patients with severe influenza infection in the U.S. between September 1, 2013 and April 1, 2014: Results of bivariable analyses and a multivariable logistic regression model.a

| Characteristicb | Not co-infected; N = 341 (%) | Co-infected; N = 103 (%) | Univariable; P value | Multivariable; odds ratio (95% CI), P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 18–49 | 117 (34.3) | 39 (39) | 0.690 | |

| 50–64 | 142 (41.6) | 43 (41.8) | |||

| >65 | 82 (24.1) | 21 (20.4) | |||

| Sex | Female | 171 (50.2) | 52 (50.5) | 0.952 | |

| Male | 170 (49.9) | 51 (49.5) | |||

| Race (N = 393) | White | 184/298 (61.7) | 58/95 (61.1) | 0.404 | |

| Black | 92/298 (30.9) | 26/95 (27.4) | |||

| Other | 22/298 (7.4) | 11/95 (11.6) | |||

| Ethnicity (N = 403) |

Hispanic | 43/308 (14.0) | 14/95 (14.7) | 0.850 | |

| Not Hispanic | 265/308 (86.0) | 81/95 (85.3) | |||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 (N = 439) | >30 | 182/339 (53.7) | 51/100 (51.0) | 0.891 | |

| 30–39 (obese) | 108/339 (31.9) | 34/100 (34.0) | |||

| ≥40 (morbidly obese) | 49/339 (14.5) | 15/100 (15.0) | |||

| Admission to a hospital or SNF/LTEC stay in the prior year | Yes | 117 (34.3) | 33 (32.0) | 0.251 | |

| No | 133 (39.0) | 34 (33.0) | |||

| Unknown | 91 (26.7) | 36 (35.0) | |||

| Comorbidities | Asthma | 64 (18.8) | 17 (16.5) | 0.602 | |

| COPD or other chronic lung disease (N = 443) | 81/340 (23.8) | 25 (24.3) | 0.914 | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 110 (31.4) | 19 (18.5) | 0.007 | 0.41 (0.23–0.73), 0.003 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 108 (31.7) | 31 (30.1) | 0.763 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 60 (17.6) | 12 (11.7) | 0.151 | ||

| Liver disease | 20 (5.9) | 9 (8.7) | 0.301 | ||

| Malignancy, received chemotherapy in past 6 mo | 19 (5.6) | 8 (7.8) | 0.414 | ||

| HIV infection | 8 (2.3) | 1 (1.0) | 0.385 | ||

| Dementia | 11 (3.2) | 3 (2.9) | 0.873 | ||

| Other neurologic diseases | 38 (11.1) | 11 (10.7) | 0.895 | ||

| History of transplant | 31 (9.1) | 5 (4.9) | 0.167 | ||

| Received steroid within the past month | 21 (6.2) | 11 (10.7) | 0.120 | ||

| Received biologics within the past month (N = 443) | 8/340 (2.4) | 1 (1.0) | 0.391 | ||

| FTT or malnutrition (N = 443) | 13/340 (3.8) | 5 (4.9) | 0.642 | ||

| Current smoker (N = 442) | 107 (31.4) | 24/101 (23.8) | 0.141 | ||

| White blood cell count on admission to ICU, K/uL (N = 443) | >11 (Leukocytosis) | 102/340 (30.0) | 52 (50.5) | <0.0001 | 3.7 (2.2–6.2),<0.001 |

| 3.5–11 (Normal) | 211/340 (62.1) | 36 (35.0) | Reference | ||

| <3.5 (Leukopenia) | 27/340 (7.9) | 15 (14.6) | 2.0 (0.94–4.4), 0.070 | ||

| SOFA score on admission to ICU; mean (sd) (N = 440)c | 7.5 (4.3) | 9.3 (4.2) | 0.0001 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2), 0.001 | |

| Initial chest X-ray quadrants with infiltrated | ≥2 | 172 (50.4) | 61 (59.2) | 0.118 | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; SNF, skilled nursing facility; LTEC, long-term extended care facility; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; FTT, failure to thrive; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; sd, standard deviation.

The multivariable analysis included all variables with p < 0.05 in the bivariable analysis.

When there are missing data for a specific variable, the n for subjects with data on this variable is indicated in the far left column.

SOFA score is determined by the following laboratory or clinical criteria: PaO2/FiO2; Glasgow coma scale; mean arterial pressure or requiring administration of vasopressor; bilirubin; platelet count; creatinine or urine output.

Determined by data abstracter by visual review of chest X-ray.

Of the patients co-infected with a bacterial pathogen, 34 (29.8%) died, and of the patients not co-infected with a bacterial pathogen, 63 (16.0%) died. Bacterial co-infected patients were significantly more likely to die (OR 2.2 [1.4–3.6], p = 0.001) than patients not co-infected with a bacterial pathogen in univariable analysis. When controlling for disease severity by the SOFA score, patients co-infected were still more likely to die (OR 1.8 [1.1–3.1], p = 0.024). Patients co-infected with S. aureus were not more likely to die than patients with other bacterial co-infections in univariable analysis (OR 1.1 [0.49–2.5], p = 0.8) or when controlling for SOFA score (OR 1.1 [0.5–2.7], p = 0.75). Patients who had a bacterial co-infection had a longer hospital stay (26.5 days vs 13.6 days; p < 0.0001), had a longer ICU stay (14.6 days vs 7.9 days; p = 0.003) and had a greater delay in the initiation of administration of an antiviral (6.9 days vs 5.3 days; p = 0.02) than patients without bacterial co-infection. Each of these last three outcomes were not significant, however, when controlling for the admission SOFA score.

Autopsy data, available for only 12 subjects, revealed that four (25%) had bacterial superinfection, of whom three had known bacterial co-infection from cultures obtained prior to death (all with S. aureus). One did not have a causative organism cultured.

Viral respiratory co-infections were identified in 23/507 (4.5%) of patients. The viral pathogens included 8/23 (34.8%) rhinovirus/enterovirus, 4/23 (17.4%) respiratory syncytial virus, 3/23 (13.0%) each adenovirus, coronavirus and parainfluenza virus and 2/23 (8.7%) human metapneumovirus. Patients with viral co-infection were more likely to have leukemia (p = 0.004), lymphoma or myeloma (p < 0.001), a history of transplantation (p < 0.001) and to have received chemotherapy in the previous six months (p = 0.007) in bivariable analysis. Nine (39.1%) patients with viral co-infection died. Patients with a viral co-infection were significantly more likely to die (OR 3.1 [1.3–7.4], p = 0.010) than patients without a viral co-infection in bivariable analysis. When controlling for underlying comorbidities of leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma and transplantation, patients with viral co-infection were not significantly more likely to die (OR 0.78 [−0.13 to 1.7], p = 0.094).

5. Discussion

In patients with severe influenza infection during 2013–2014, the first postpandemic season in the U.S. in which influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 was the predominant circulating influenza strain, respiratory co-infections were common, were associated with higher mortality. They resulted in increased resource allocation, as defined by longer hospital and ICU stay, although this was not significant when accounting for admission SOFA score. In this study of 507 patients with severe influenza, 22.5% had bacterial co-infection and 4.5% had viral co-infection. Of the 99 patients who died, more than one-third had a bacterial co-infection. S. aureus was the most prevalent species causing respiratory bacterial co-infection, and MRSA was the most common community-acquired pathogen. This supports the idea that S. aureus has a synergistic relationship with influenza A (H1N1) pdm09, even for people in the community. Patients with bacterial co-infection were less likely to have cardiovascular disease, were more likely to have leukocytosis on ICU admission and tended to have a higher ICU admission SOFA score.

In our cohort, among the 22.5% of patients with a bacterial co-infection, 12.2% had community-acquired and 10.3% had hospital-acquired co-infections. Our rates were lower than those reported in the 2009–2010 season. During that pandemic year, rates of 17.5–25% for community-acquired co-infections and 33% for combined community- and hospital-acquired co-infections were reported although the criteria for defining a co-infected patient varied by study [18], [19], [20]. Four (25%) out of 12 autopsies in our cohort showed evidence of bacterial pneumonia, but one of these four patients did not have a positive culture despite collection of respiratory and blood cultures. Our recorded 30-day incidence of bacterial co-infection may therefore be an underestimate, reflecting the poor sensitivity of lower respiratory cultures in the setting of empiric antimicrobial therapy.

Bacterial co-infection was associated with higher mortality. This is despite the fact that 92.1% of our cohort received antibacterial drugs during hospitalization. The pathogenesis of influenza and bacterial co-infection is synergistic and complex. The disease process involves numerous viral and bacterial virulence factors interacting with the host immune system and adversely affecting respiratory physiology. In pandemic seasons, compared with usual epidemic seasons, a high proportion of the mortality from influenza infection, often complicated by bacterial co-infection, occurs in young, previously healthy people as a result of an aberrant immune response to the virus [23].

S. aureus was the most common species isolated in our cohort. In a 2009 study on co-infections in severely ill patients with influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 infection in 35 U.S. ICUs, S. aureus was also found to be the most common bacterial pathogen [10]. S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae and S. pyogenes were all also present among community-acquired pathogens but surprisingly, P. aeruginosa was more common than any of these species. P. aeruginosa is increasingly being described as a co-pathogen with influenza [24]. As expected, we recorded a high prevalence of Gram negative co-infections among hospital-acquired infections. In our cohort 31.3% of hospital-acquired co-infections were due to S. aureus and 19.4% were due to each Pseudomonas species and Enterobacteriaceae. In studies evaluating the agents of hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia without an underlying influenza infection, 14–28% have been attributed to S. aureus, 16–34% have been attributed to P. aeruginosa and 19–35% have been attributed to Enterobacteriaceae [25]. The prevalence of S. aureus among hospital-acquired bacterial co-infections in our cohort was slightly higher than what would be expected in patients without influenza infection.

Co-infection resulted in greater resource allocation as measured by hospital length of stay and ICU length of stay in bivariable but not multivariable analysis. Moreover, time from symptom onset to administration of an antiviral effective against influenza was delayed in co-infected patients in bivariable but not multivariable analysis. A number of studies have shown an association between early effective antiviral use in influenza infection and reduced ICU admission and mortality, suggesting that the delay in our cohort may have been detrimental [26].

Risk factors for bacterial co-infection included lack of cardiovascular disease as well as leukocytosis and increased SOFA score on ICU admission. It is unclear why cardiovascular disease appeared to be protective in our cohort; it may be that statin use confers anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects that may reduce risk of co-infection. This possible association warrants further study.

Viral co-infection was associated with increased mortality in our cohort in bivariable but not in multivariable analysis when controlling for underlying comorbidities. Studies evaluating this previously have been mixed [27], [28], [29]. The association between viral co-infection and mortality require further research.

Our study had several limitations. The majority of subjects were treated at U.S. tertiary care centers; thus, our findings may not be generalizable to any population of severely ill influenza patients. We did not include subjects admitted after April 1, 2014. Therefore, we did not include the final part of the influenza season, likely excluding disproportionately patients with severe influenza B infection, who may experience a different risk of bacterial and viral co-infection from influenza A (H1N1) pdm 09 patients. Management of patients and bacterial identification and susceptibility testing was not standardized. Rapid diagnostic testing may have resulted in some missed cases of influenza among ICU patients. However, this was the sole method used in only 3 of 33 studied hospitals. While we used a standardized data collection form, some variables were not available for some subjects. Finally, as a retrospective study, selection bias and immortal time bias may have affected our choice of subjects and our analysis, respectively.

This study highlights the importance of bacterial co-infection in the pathogenesis of severe influenza infection. Preventive measures to address co-infection include ensuring high rates of influenza, S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae vaccination, appropriate timing of antivirals and early and appropriate antibiotic therapy targeting MRSA and Pseudomonas. Therapy targeting MRSA particularly in cases of community-acquired pneumonia is important. Understanding the complex and synergistic relationship between bacteria and influenza is vital in decreasing mortality in future seasonal and pandemic influenza seasons.

Competing interests

None.

Funding

This publication was made possible in part by Grant Number D33HP25768 from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA).

Ethical approval

IRB approval received from UofC (IRB 14-0383) and each participating hospital.

References

- 1.Thompson W.W., Shay D.K., Weintraub E., Brammer L., Cox N., Anderson L.J. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;289(2):179–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brundage J.F., Shanks G.D. Deaths from bacterial pneumonia during 1918–19 influenza pandemic. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008;14(8):1193–1199. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.071313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morens D.M., Taubenberger J.K., Fauci A.S. Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;198(7):962–970. doi: 10.1086/591708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murata Y., Walsh E.E., Falsey A.R. Pulmonary complications of interpandemic influenza A in hospitalized adults. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;195(7):1029–1037. doi: 10.1086/512160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morens D.M., Fauci A.S. The 1918 influenza pandemic: insights for the 21st century. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;195(7):1018–1028. doi: 10.1086/511989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson N.P.A.S., Mueller J. Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918–1920 Spanish influenza pandemic. Bull. Hist. Med. 2002;76(1):105–115. doi: 10.1353/bhm.2002.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chien Y.-W., Klugman K.P., Morens D.M. Bacterial pathogens and death during the 1918 influenza pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361(26):2582–2583. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0908216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCullers J.A. The co-pathogenesis of influenza viruses with bacteria in the lung. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014;12(4):252–262. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seki M., Kosai K., Yanagihara K., Higashiyama Y., Kurihara S., Izumikawa K. Disease severity in patients with simultaneous influenza and bacterial pneumonia. Intern. Med. 2007;46(13):953–958. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rice T.W., Rubinson L., Uyeki T.M., Vaughn F.L., John B.B., Miller R.R. Critical illness from 2009 pandemic influenza A virus and bacterial coinfection in the United States. Crit. Care Med. 2012;40(5):1487–1498. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182416f23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwarzmann S.W., Adler J.L., Sullivan R.J., Marine W.M. Bacterial pneumonia during the Hong Kong influenza epidemic of 1968–1969. Arch. Intern. Med. 1971;127(6):1037–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin C.M., Kunin C.M., Gottlieb L.S., Finland M. Asian influenza A in Boston, 1957–1958. II. Severe staphylococcal pneumonia complicating influenza. AMA Arch. Intern. Med. 1959;103(4):532–542. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1959.00270040018002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robertson L., Caley J.P., Moore J. Importance of Staphylococcus aureus in pneumonia in the 1957 epidemic of influenza A. Lancet. 1958;2(August (7040)):233–236. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(58)90060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillet Y., Issartel B., Vanhems P., Fournet J.-C., Lina G., Bes M. Association between Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying gene for Panton-Valentine leukocidin and highly lethal necrotising pneumonia in young immunocompetent patients. Lancet. 2002;359(9308):753–759. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07877-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finelli L., Fiore A., Dhara R., Brammer L., Shay D.K., Kamimoto L. Influenza-associated pediatric mortality in the United States: increase of Staphylococcus aureus coinfection. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):805–811. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watt J.P., Wolfson L.J., O’Brien K.L., Henkle E., Deloria-Knoll M., McCall N. Burden of disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374(9693):903–911. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaussee M.S., Sandbulte H.R., Schuneman M.J., Depaula F.P., Addengast L.A., Schlenker E.H. Inactivated and live, attenuated influenza vaccines protect mice against influenza: Streptococcus pyogenes super-infections. Vaccine. 2011;29(21):3773–3781. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martín-Loeches I., Sanchez-Corral A., Diaz E., Granada R.M., Zaragoza R., Villavicencio C. Community-acquired respiratory coinfection in critically ill patients with pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus. Chest. 2011;139(3):555–562. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Estenssoro E., Ríos F.G., Apezteguía C., Reina R., Neira J., Ceraso D.H. Pandemic 2009 influenza A in Argentina: a study of 337 patients on mechanical ventilation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010;182(1):41–48. doi: 10.1164/201001-0037OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nin N., Soto L., Hurtado J., Lorente J.A., Buroni M., Arancibia F. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus infection with respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. J. Crit. Care. 2011;26(2):186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah N.S., Greenberg J.A., McNulty M.C., Gregg K.S., Riddell J., Mangino J.E. Severe influenza in 33 US hospitals, 2013–2014: complications and risk factors for death in 507 patients. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2015;(July):1–10. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dawood F.S., Chaves S.S., Pérez A., Reingold A., Meek J., Farley M.M. Complications and associated bacterial coinfections among children hospitalized with seasonal or pandemic influenza, United States, 2003–2010. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;209(5):686–694. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cillóniz C., Ewig S., Menéndez R., Ferrer M., Polverino E., Reyes S. Bacterial co-infection with H1N1 infection in patients admitted with community acquired pneumonia. J. Infect. 2012;65(3):223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones R.N. Microbial etiologies of hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010;51(Suppl. 1):S81–87. doi: 10.1086/653053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viasus D., Paño-Pardo J.R., Pachón J., Campins A., López-Medrano F., Villoslada A. Factors associated with severe disease in hospitalized adults with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 in Spain. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011;17(5):738–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drews A.L., Atmar R.L., Glezen W.P., Baxter B.D., Piedra P.A., Greenberg S.B. Dual respiratory virus infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1997;25(6):1421–1429. doi: 10.1086/516137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Renois F., Talmud D., Huguenin A., Moutte L., Strady C., Cousson J. Rapid detection of respiratory tract viral infections and coinfections in patients with influenza-like illnesses by use of reverse transcription-PCR DNA microarray systems. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48(11):3836–3842. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00733-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin E.T., Kuypers J., Wald A., Englund J.A. Multiple versus single virus respiratory infections: viral load and clinical disease severity in hospitalized children. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses. 2012;6(1):71–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]