Summary

Although definitions of mass gatherings (MG) vary greatly, they consist of large numbers of people attending an event at a specific site for a finite time. Examples of MGs include World Youth Day, the summer and winter Olympics, rock concerts, and political rallies. Some of the largest MGs are spiritual in nature. Among all MGs, the public health issues, associated with the Hajj (an annual pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia) is clearly the best reported—probably because of its international or even intercontinental implications in terms of the spread of infectious disease. Hajj routinely attracts 2·5 million Muslims for worship. WHO's global health initiatives have converged with Saudi Arabia's efforts to ensure the wellbeing of pilgrims, contain infectious diseases, and reinforce global health security through the management of the Hajj. Both initiatives emphasise the importance of MG health policies guided by sound evidence and based on experience and the timeliness of calls for a new academic science-based specialty of MG medicine.

This is the first in a Series of six papers about mass gatherings health

Introduction

Definitions of mass gatherings (MGs) vary greatly, with some sources specifying any gathering to be an MG when more than 1000 individuals attend, whereas others require the attendance of as many as 25 000 people to qualify.1, 2 Irrespective of the definition, MGs represent large numbers of people attending an event that is focused at specific sites for a finite time. These gatherings might be planned or unplanned and recurrent or sporadic. Examples of MGs include World Youth Day, the summer and winter Olympics, rock concerts, and political rallies. MGs pose many challenges, such as crowd management, security, and emergency preparedness. Stampedes and crush injuries are common, the result of inevitable crowding. Outdoor events are associated with complications of exposure, dehydration, sunburn, and heat exhaustion. Other health hazards arise from lack of food hygiene, inadequate waste management, and poor sanitation. Violence is unpredictable and difficult to mitigate whether the MG is a political rally or a sporting competition. With few exceptions, however, the rates of morbidity and mortality resulting from these hazards are rarely increased outside the event. Global MGs, however, can lead to global hazards. Mitigation of risks requires expertise outside the specialty of acute care medicine, event planning, and venue engineering.

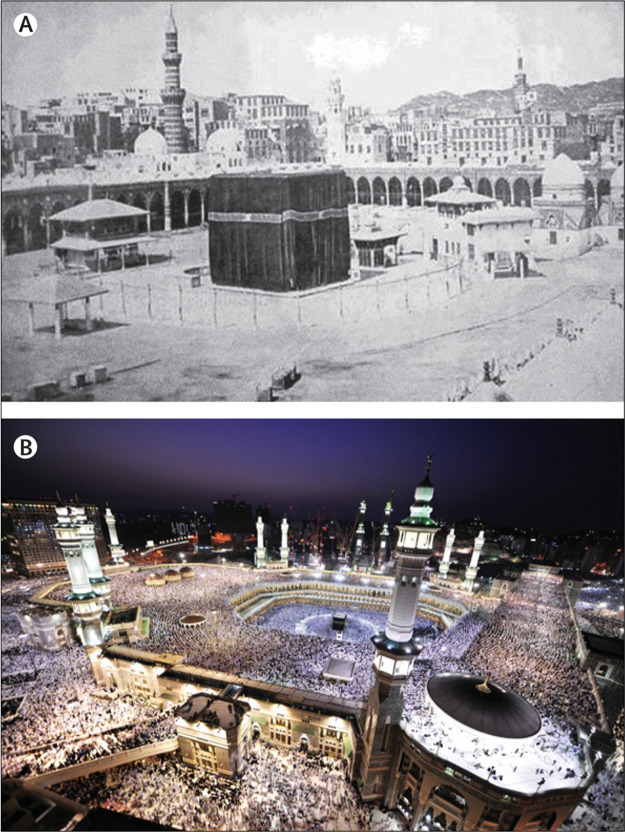

For centuries, Muslim pilgrims have converged in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, for the Hajj (figure 1 ) to participate in a series of sacred rituals that define Islam. With about 1·6 billion Muslims and the obligation on believers to attend Hajj at least once in their lifetimes, this event has become the largest annually recurring MG in the world, with attendance reaching more than 2·5 million in 2009 despite warnings about pandemic influenza. Pilgrims come from more than 183 countries, leading to enormous diversity in terms of ethnic origin and socioeconomic status. Men, women, and children of all ages attend Hajj together; however, a disproportionate number of people will be middle aged or older before they can afford the journey. Comorbidities are common. The public health implications of the Hajj are huge—nearly 200 000 pilgrims arrive from low-income countries, many will have had little, if any, pre-Hajj health care, added to which are the extremes of climate and crowding, rugged terrain, mingling of populations from around the world, and migration into the country of livestock, butchers, and abattoir workers.

Figure 1.

The Hajj in the 19th (A) and 21st centuries (B)

Pilgrims encircling the Ka'aba, the main mosque in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, during the Hajj. Part A is courtesy of Saudi Ministry of Health.

Saudi Arabia's safety and security policies for Hajj attendees are well developed after decades of planning the annual event. Lessons learned have led to comprehensive programmes that are continually revised and coordinated by government sectors. Public health has involved global partners for decades. Far from being the only MG that affects global health, the Hajj is a useful model to understand the nature of risk management and the benefits of international collaboration and cooperation.

Development of MGs

Pilgrimage is central to many belief systems and also appeals to mankind's recurring desire to be homo viator—a universal figure common to many cultures and civilisations, who wanders in search of spiritual enlightenment. In Hellenic civilisation, Delphi—home to Pythia the Oracle—was long a focus for pilgrimage.3 Ancient tribal populations such as the Huichol of western Mexico, the Lunda of central Africa, and the Shona people of southwest Africa all included pilgrimage in their cultures.4 Institutionalised pilgrimage came to prominence with the advent of world religions. Buddhism invites pilgrimage to Nepal, the birthplace of Siddharta. Hindus journey to Benares in India, and followers of Judaism to Jerusalem. Christendom has a complex history of pilgrimages through the ages including the modern era. Until the advent of modern air travel, the journey was associated with the greatest risks. A review of the historical data for the Hajj shows these dangers:

“…the oscillatory movement of the camel produces miscarriages, followed frequently by haemorrhage and death of the infant and mother. The caravan however cannot stop, and it is impossible to nurse efficiently while the (journey) continues. If any portion of the caravan stopped it would certainly be attacked…”5

Religious MGs

Kumbh Mela is a huge Hindu pilgrimage held at various locations along the river Ganges according to the zodiac positions of the sun, moon, and Jupiter. Purification rites involve bathing in the Ganges and are believed to interrupt the cycle of reincarnation. The highest holy days arise every 144 years, but the normal Kumbh Mela is celebrated every 3 years, and often attract thousands of non-Hindu enthusiasts. This is the largest human gathering, so large that in 2001 movements of the amassed individuals could be seen from space.6, 7 The Ardh Kumbh Mela in 2007 attracted 70 million pilgrims over 45 days in Allahabad; on the most auspicious day of the festival, more than 5 million participated.8 Celebrations are accompanied by singing, religious readings, and ritual feeding of holy men and the poor. Managing rival sects is a recurring challenge. Administrators overseeing the event have to negotiate bathing schedules. Clashes have resulted in deaths—eg, in 2010, a vehicle carrying members of the Juna sect struck several people, setting off a stampede.9 In 1954, a stampede killed 500 people.10

The festival probably contributed to the 1817–24 Asiatic cholera pandemic. Pilgrims are believed to have carried the bacteria from an endemic area in the lower Ganges to populations in the upper Ganges, from there to Kolkata and Mumbai, and across the subcontinent. British soldiers and sailors took it home to Europe and then to the far east.11 The epidemic ended abruptly in 1824 after a very cold winter. Although cholera returned to the Kumbh Mela in 1892, authorities of the Hardiwar Improvement Society reacted to contain the outbreak.12 Diarrhoeal diseases, including cholera, continue to be a risk at the gathering despite rapid monitoring and prompt public health interventions.13

Another pilgrimage with a focus on water and religious rites is to Lourdes, France. This village in the Pyrenees attracts more than 5 million Catholics and other enthusiasts every year. Their destination is a shrine and nearby spring where a young village girl witnessed apparitions of the Virgin Mary in the mid 1800s. Drinking and bathing in Lourdes' water is believed to ensure health and cure disease, and is featured at the Water Walk where religious stations are situated and water is available for drinking or bottling. Spring water is also routed to a series of bathing stalls used by more than 350 000 pilgrims every year.14 Although health issues have not been associated with Lourdes' waters, the French writer Emile Zola visited the spring in 1891 and provided a graphic description of the baths at the time:

“And the water was not exactly inviting. The Grotto Fathers were afraid that the output of the spring would be insufficient, so in those days they had the water in the pools changed just twice a day. As some hundred patients passed through the same water, you can imagine what a horrible slop it was at the end. There was everything in it: threads of blood, sloughed-off skin, scabs, bits of cloth and bandage, an abominable soup of ills…the miracle was that anyone emerged alive from this human slime.”15

Stampedes and fires continue to be major causes of death and injury at MGs—eg, the Sabarimala in Kerala, India, and the Feast of the Black Nazarene in Manila, Philippines. Inaccessible for 300 years after their construction, Hindu temples of Sabarimala in Kerala's Western Ghat Mountains have become increasingly popular despite the location and winter openings. With the increasing crowd sizes, tragedies have occurred. In 1952, 66 pilgrims burned to death when sheds containing fireworks caught fire, and more than 52 perished in 1999 when a hillside collapsed under the weight of 200 000 assembled worshipers triggering a stampede.16 More than 50 million attended the most recent rites in January, 2011, uneventful until the last day when a motor vehicle accident caused a panic that triggered a stampede, killing 104 people.17, 18 Although authorities offered compensation packages, they could not quell unprecedented public criticism of Kerala authorities and the national government.17

Manila's Feast of the Black Nazarene has fared a little better after religious leaders and municipal authorities joined forces to change the route of the annual Jan 9 procession after two deaths in 2008, and many stampedes and injuries caused by fireworks and trauma over the years. The authorities responsible for the MG also recruited thousands of volunteers to manage the crowds. These changes and the addition of an information campaign have helped calm crowds and reduce injuries. Despite an estimated attendance of 7–8 million in 2011, no deaths or serious injuries were reported.19

Life events and iconic and political figures

Weddings and funerals can be attended by millions of people. An estimated 1 million people gathered for the largest ever event in London, UK, the wedding of Catherine Middleton and Prince William, Duke of Cambridge. Funerals of iconic figures, typically religious leaders and political champions trigger spontaneous MGs (table ).20 More than 1 million mourners gathered in Paris, France, for François-Marie Arouet de Voltaire's funeral in 1798, a huge number in view of France's population of barely 30 million at the time, and the arduous nature of overland journeys. The funeral of the Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989 drew an estimated 6–12 million people in Tehran, Iran. 5 million mourners attended the funerals of Gamal Abdel Nasser and Abdel Halim Hafez in Cairo, Egypt, in the 1970s. Deaths of two assassinated US presidents Abraham Lincoln and John Kennedy drew crowds of millions of people along cortege routes. Pope John Paul II's funeral lasted an entire week in April, 2005. More than 4 million people gathered in Rome, Italy, from all over the world. Similarly, the funeral cortege of the Princess of Wales attracted crowds of more than 1 million along its 6·5 km journey within days of her death.

Table.

Largest peaceful mass gatherings20

| Type of event | Location | Year | Number of people (millions) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| World Expo | Fair | Shanghai, China | 2010 | 73 |

| Kumbh Mela | Religious | Allahabad, India | 2007 | 60–70 |

| Kumbh Mela | Religious | Haridwar, India | 2010 | 50 |

| Hindu temple pilgrimage | Religious | Sabarimala, Kerala, India | Annual | 5–50 |

| Arba'een, Imam Hussein's shrine | Religious | Karbala, Iraq | Annual | 9–60 |

| Funeral of C N Annadurai | Political | Tamil Nadu, India | 1969 | 15 |

| Funeral of Ayatollah Khomeini | Political and religious | Tehran, Iran | 1989 | 6–12 |

| Feast of the Black Nazarene | Religious | Manila, Philippines | 2011 (annual) | 8 |

| 25th anniversary of El Shaddai | Religious | Manila, Philippines | 2003 | 7 |

| World Youth Day and Pope's visit | Religious | Manila, Philippines | 1995 | 5 |

| Welcome to Ayatollah Khomeini | Political and religious | Tehran, Iran | 1979 | 5 |

| Funeral of Gamel Abdel Nasser | Political | Cairo, Egypt | 1970 | 5 |

| Removal of President Hosni Mubarak | Political | Cairo, Egypt | 2011 | 5 |

| Funeral of Abdel Halim Hafez | Cultural | Cairo, Egypt | 1977 | 4 |

| Funeral of Umm Kulthum | Cultural | Cairo, Egypt | 1975 | 4 |

| Funeral of Pope John Paul II | Religious | Rome, Italy | 2005 | 2–4 |

| Antiwar rally (invasion of Iraq) | Political | Rome, Italy | 2003 | 3 |

| Celebration of Red Sox victory | Sports | Boston, MA, USA | 2004 | 3 |

| Defense of workers' rights | Political | Rome, Italy | 2002 | 2–3 |

| Hajj | Religious | Mecca, Saudi Arabia | Annual | 2–3 |

| Closing mass, World Youth Day | Religious | Rome, Italy | 2000 | 2·7 |

| Beatification of Pope John Paul II | Religious | Krakow, Poland | 2002 | 2·5 |

| Gay Pride parade | Political | Sao Paolo, Brazil | 2006 | 2·5 |

| Stanley Cup parade | Sports | Philadelphia, PA, USA | 1974 | 2 |

| Republic protests | Political | Izmir, Turkey | 2007 | 2 |

| Champion Fédération Internationale de Football Association World Cup | Sports | Madrid, Spain | 2010 | 2 |

| Attukai Temple (women) | Religious | Trivandrum, Kerala, India | 2007 | 2 |

| Bicentennial of May Revolution | Cultural | Buenos Aires, Argentina | 2010 | 2 |

Political assemblies and protests

Protests during the Arab Spring in 2011 drew millions of largely peaceful protesters to central locations of Tunis, Tunisia, and then Cairo, Egypt. More than 5 million were present when the departure of Egypt's President Hosni Mubarak was announced in February, 2011. Other MGs include political protests of the antiwar movement during the Vietnam War. 1968 was marked by massive student marches in major European, Asian, and Latin American capitals. Chicago, IL, USA, had a particularly violent succession of MGs that became riots after the assassination of the civil rights leader Martin Luther King and again a few months later during antiwar protests at the Democratic National Convention. By contrast, European marches in protest of the US-led invasion of Iraq were larger and more peaceful. More than 3 million attended the largest march in Rome in 2003 (figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

The 2003 Rome protest against the Iraq war was peaceful, but violence can mar mass gatherings

In 1999, antiglobalisation protesters assembled in Seattle, WA, USA, ahead of a scheduled World Trade Organization meeting. Along with international anticorporate interests and assorted domestic supporters, they successfully occupied Seattle's downtown core and the convention centre. Violence increased during the 5 days, culminating in a full-scale riot after anarchists joined in and police responded with tear gas and rubber bullets. The Battle in Seattle as it came to be known, caused damages that were estimated at more than US$3 billion. Despite the violence and very large crowds, estimated to be hundreds of thousands of people, no deaths or serious injuries were reported. Political events of a less controversial nature also attract large crowds—eg, the inauguration of President Elect Barack Obama in 2008 attracted more than 1 million spectators who gathered in Washington, DC, USA, for hours in freezing January temperatures (figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

Crowds gathered in subzero temperatures to watch Barack Obama's inauguration in 2009

Celebrations, sports events, and music concerts

Since the second half of the 20th century, international sporting events such as the Olympics and Fédération Internationale de Football Association World Cup have attracted global audiences largely because of affordable air travel. Global attendance is associated with a risk of imported disease. Vancouver, BC, Canada, had a measles outbreak during the winter Olympics of 2010 (figure 4 ). The infection spread to remote areas of British Columbia in weeks, causing substantial morbidity among its indigenous peoples.21 Occasionally, the athletes themselves transmit infections. An outbreak of chicken pox occurred among members of the Maldives volleyball squad at Doha's Asian Games in 2006 and was successfully managed by use of quarantine, antiviral drugs, and vaccine.22 International organisers of the Olympics have paid close attention to security risks after 11 Israeli athletes and coaches died in a gunfight with terrorists at the Olympics in Munich, Germany, in 1972. One bystander was killed as a result of a bomb explosion at Atlanta's Olympic Park, GA, USA, in 1996.23, 24

Figure 4.

Vancouver was struck by an outbreak of measles during the 2010 Winter Olympics

Violent sports fans are as old as history. In 532, the Nika riots in Constantinople pitted rival charioteer factions and athletes against each other and Emperor Justinian. During the 1 month insurrection that ensued, half the city was destroyed and more than 30 000 people died.25 Although sports violence continues to be a risk during matches between rival teams, the massive crowds, crowds in motion, and immovable barriers cause the greatest loss of lives. The worst sports riot in history occurred in South America during a 1964 football playoff game between Peru and Argentina when fans responded in protest after a controversial decision to annul a goal by Peru. Police responded by throwing teargas canisters into the grandstand. More than 500 fans were injured and another 318 died. Most were crushed trying to escape the locked stadium, others died from teargas asphyxiation. The disaster in Hillsborough, UK, in 1989 was the worst stadium tragedy in British history. 96 fans died and another 766 were injured as crowds surged into the stadium crushing others in front who were pinned against fences. Many of the deaths resulted from compressive asphyxia while standing. Ineffective crowd control and poorly designed venues have also resulted in deaths at music festivals, most recently in 2010 during the Love Parade in Duisburg, Germany, in which 21 people were crushed to death and 500 were injured as a result of a stampede in a narrow tunnel. Occasionally, MGs cause structural stresses that threaten safety and security. In 1987, the 50th anniversary of the Golden Gate Bridge, San Francisco, CA, USA, was celebrated by closing it to vehicular traffic. Though not catastrophic, the suspension cables had the greatest load factor ever when 500 000 pedestrians crowded onto the deck, flattening its centre span.26

The Hajj

Although the Hajj was undertaken in the Middle East before the arrival of Islam, the movements and rituals of pilgrims today have not changed since the Prophet Mohammad inaugurated the Islamic Hajj in his lifetime.27 It has been recorded in Arabic literature known as Adab Al Rihla. Persian literature records Hajj in the Safarnameh (travel letter). At the core of Islamic belief is trust and this trust has been best exemplified by the risks Muslims take when travelling. The Muslim individual must trust in his Maker and, in ancient times, in the benevolence of strangers who would host him on his perilous journey to Mecca. Nowadays, as a result of the dissemination of Islam across the world, Hajj removes national, cultural, and social boundaries between diverse people like no other event.

Imperial powers and 19th century Hajj

Hajj has been the focus of public health initiatives for centuries, as shown in contemporary medical reports.28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 During the 19th century, the Hajj attracted the interest of European powers, particularly the maritime travel to the Hajj, which dominated until the arrival of air travel. Colonial powers at the time were suspicious of political Islam, which was referred to as wahabism. Direct engagement in Hajj-related affairs was seen as too intrusive by politically savvy imperialists who recognised the sanctity of this little understood religious pilgrimage. Instead, supervision, albeit displaced, and management of Hajj were gradual processes, including surveillance, regulation, secure passage through the Red Sea and protection of British littoral interests, and eventually formal organisational processes, which would quickly become central to these hidden concerns. Imperial organisations linked cholera morbus, a non-epidemic diarrhoea, to Hajj, allowing a public health industry to develop that used health concerns to control immigration, pilgrim passports, proof of sufficient funds to allow return travel, maritime regulation, and vessel quarantine procedures.

By the mid 19th century, most of the Muslim populations using maritime travel for Hajj were from the Malay Peninsula and Indian subcontinent. About 2000 pilgrims travelled from the Malay Peninsula and between 5000 and 7000 arrived from the Indian subcontinent. Although there are few reliable data, the total number of pilgrims was estimated to be 10 000.38

“According to the Turko-Egyptian Sanitary Commissioners at Mecca, the number of Mohammedan pilgrims collected in and about the Holy City…amounted to two hundred thousand persons; composed of natives of Turkey, India, Egypt, Morocco, Arabia, Syria, Persia, Java etc.” 29

Most travellers came in small vessels of 100–300 tons under different international aegis. Departures were concentrated around Singapore, Calcutta and Madras in India, Aceh in Indonesia, and other regional cities. Most pilgrims then, like today, disembarked in Jeddah, though some would land on southern Arabian coastal ports and then make a land journey through Yemen to Hijaz. Well into the 20th century, the conditions of passage were often appallingly cramped and unsanitary.34 Many people died along the route from infection and dehydration. 83 pilgrims died on board a maritime vessel, which had embarked from Jeddah with 520 pilgrims en route home to Singapore.34

“When she drew abreast of the watcher she proved to be a pilgrim ship; the afternoon being hot, the travellers had all crowded to the port side to catch what little wind was stirring. Their numbers were so great that they appeared to cover all the deck space, while the ship was unable to right herself from the list…”34

Efforts to manage Hajj were initiated by Dutch-Indonesian authorities, not for wholly altruistic reasons. The Dutch had established an association between returning pilgrims and societal unrest, so they introduced heavily surcharged passports as a way of restricting the number of travellers to Mecca. The ruling empires focused on health issues and justified inspections of Hajj sites for compliance with contemporary public health directives, often focusing on quarantine as a means of protection at a time when many international arrivals, including maritime travellers, were reaching Mecca. Their inspections were disappointing—the Annual Sanitary Commission visited the sites of Hajj and noted that the focus was not on prevention, but rather on the easy option of quarantine.37

When cholera was reported at Hagar's Well within the holy mosque in Mecca, the British Consul at Jeddah requested a scientific assessment. Samples were analysed at the Royal College of Chemistry in the South Kensington Museum, London, UK, and compared with those of London sewage, which was a source of cholera at that time. Recommendations after their alarming findings were sent to the Secretary of State for India who reported the well to be infected with the bacterium.35, 36

Similarly, entrepôt cholérique (cholera reservoir) was noted when authorities visited pilgrims from India intending to do the Hajj. These pilgrims were routinely detained on the island of Camaran as a quarantine station in the Red Sea to restrict the ingress of cholera into the holy sites.37, 38 Pilgrims were detained for 5–10 days without adequate provisions or clean water. The long exposure to sun, however, was thought to be beneficial for elimination of infection. After quarantine, pilgrims were often permitted into the site. Results of later studies showed a link between the pilgrims quarantined on Camaran with a series of eight subsequent outbreaks. The conclusions drawn from a review of these events at an international public health meeting at the International Sanitary Conference of Paris, France, 1895, were that the “Turkish possession of Camaran remains the greatest hindrance to the abolition of cholera at Mecca”.37

Infection was a frequent feature of the Hajj in the 19th and 20th centuries, not unexpected since infectious disease medicine became better elucidated and the fascination with the developing specialty increased. Epidemics of smallpox occurred in Iraq and Sudan between October, 1928, and April, 1929. A small epidemic of plague occurred in upper Egypt and a larger one in Morocco (161 cases).34 653 cases of typhus were reported in Egypt and 32 in Palestine during the same period.34 These findings led to some strong recommendations that are still relevant:

“The yearly pilgrimage will remain a danger to all the countries from which pilgrims are drawn as long as the conditions of transport and accommodation remain…as at present. Efficient reorganization of the pilgrimage in every direction is needed and should be facilitated by the governments of the large number of the countries involved.”34

By the early 20th century, non-Muslim European powers were heavily engaged in the management of the Hajj and would remain so until modern Saudi Arabia came into existence and acquired financial independence through petrochemical wealth. The comparison of Hajj in the imperial era with the modern Hajj shows the absence of Muslim public health experts or authorities in managing this pilgrimage.39, 40 This absence would gradually change and with the arrival of Ibn Saud's modern kingdom and its investments in Hajj. From this point, Muslims would solely administer the modern Hajj in its entirety.41, 42

Modern Hajj

The Islamic calendar is a lunar calendar, so the date of the Hajj moves forward by 10–11 days every year, presenting planners with additional challenges of health risks that are associated with seasonal variation. Temperature fluctuations in Mecca might be extreme depending on the time of year; daytime highs can be 40°C and higher, and night-time temperatures occasionally fall to 10°C. Hajj can coincide with the northern hemisphere's influenza season, as in 2009, increasing public health risks.43, 44, 45, 46, 47 Attendance in 2009 was not blunted despite official recommendations encouraging pregnant women, and elderly and very young people to stay at home.48 More than 2·5 million people attended, including 1·6 million foreign citizens, 753 000 of whom did not have valid Hajj permits.49 To put the event in its local context, the influx of pilgrims is so great that it trebles the resident population of Mecca, which is normally 1·4 million.

Access to the Hajj for pilgrims has changed greatly with air travel gradually replacing maritime and overland travel. In the past decade, the breakdown includes about 92% of pilgrims arriving by air, 1% making the maritime journey, and 7% travelling over land.50 Although a few pilgrims will arrive at Medina's international airport, Jeddah remains the major port of entry for all travellers as it has been for centuries. Increasing numbers of people attending the modern Hajj led to a 1980 decision by Saudi aviation authorities to partition Jeddah's King Abdulaziz International Airport and create a separate south terminal to serve all pilgrims. Now two-thirds completed, the terminal's capacity is 80 000 travellers at any time. When completed, its final capacity will be greater than 30 million passengers per year. Important new features include health-screening systems, customs, and immigrations security. Each of its 18 hubs receives pilgrim flights; all hubs have two examination rooms. The terminal also features large holding areas that allow efficient reviews of selected arrivals in segregated parts of the terminal. This permits verification of the immunisation status and administration of any prophylactic drugs and vaccines according to set protocols.

The overall design of the terminal permits visitors arriving without required visas and health records to be managed outside the main flow of pilgrims who continue through the facility to join assigned groups or agents who are responsible for coordinating details of travel and housing. These regulated services will also escort their charges through the Hajj site. In Islam, Umrah is a shorter pilgrimage to Mecca. Although not compulsory, Umrah draws an additional 5 million pilgrims per year to the country; Jeddah's airport plays a major part throughout the year, controlling access and enforcing health protocols. Groups exiting the country and returning home are also monitored, allowing comparative studies between the two populations. At various times of the year, but most intensely during the Hajj season, public health teams, both stationary and mobile, use mobile devices to monitor inbound and outbound populations. Protocols are based on regularly reviewed case definitions. Gathered data are sent to centralised databases for real-time analysis. Many diseases are monitored during a Hajj season. Those given specific attention every year include both mild and severe respiratory diseases, food poisoning and gastroenteritis syndromes, haemorrhagic fevers, and meningococcal diseases. Reports of all diseases, but particularly those with immediate effect worldwide—severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), influenza, cholera, yellow fever, polio, plague, meningitis, and viral haemorrhagic syndromes—are expedited to WHO epidemiologists who work closely with Saudi authorities to analyse information and coordinate a response. The airport is also equipped with clinics for management of medical problems.

Rites of the Hajj

Humility, faith, and unity are emphasised throughout the Hajj. The pilgrims wear simple clothing, women and men comingle, women are enjoined not to cover their faces, children and adults of all ages are included, and families journey together. On arrival in Mecca, Hajj pilgrims do a series of synchronised acts based on events in the lives of Ibrahim (Abraham), his wife Hajra (Hagar), and their son Ishmael. Each pilgrim does an initial circumambulation (tawaf) around the central Ka'aba seven times. When completed, the pilgrim leaves for Arafat, about 22 km east of Mecca. Hajj culminates in Arafat on the Day of Standing, when all 2·5–3·0 million visitors stand and supplicate together on the mountain. Mount Arafat is believed to be the site of Mohammad's last sermon to his followers. Many people attempt to pray at the summit believing prayers there are the most blessed. On the way to Arafat, the pilgrims make overnight stops for prayers and contemplation in Mina. Leaving Arafat, the pilgrims return to Muzdaliffah, where stones are gathered; on the way to Mina, they stop at Jamarat bridge to throw stones at the pillars that are effigies of Satan. When the pilgrimage is complete, the new Hajjee (pilgrim who has completed the Hajj) makes an animal sacrifice thanking Allah for accepting his Hajj. This is often a proxy sacrifice because the Saudi Government has established modern abattoirs that are staffed by professionals who will do this on behalf of the pilgrims. Meat is then distributed to the poor, family, and friends. The final farewell is undertaken with another seven circuits around the Ka'aba. Muslim men on completion of a successful Hajj shave their heads. After completion of the Hajj, most pilgrims exit the country at Jeddah airport, which has congestion so great that the telecommunications infrastructure has to be constantly updated to allow sufficient capacity. A smaller number of pilgrims will visit the holy mosque in Medina. Some will also visit tourist sites in the Hijaz and the old city of Jeddah.

Hajj culture

Because all Hajj pilgrims travel as part of small informal groups, there is order in what could otherwise be chaos. Groups take their shepherding of individual pilgrims seriously, with easily identified group leaders who carry placards and flags and lead the entire group through the rituals without losing stragglers, infirm individuals, or temporarily distracted people. Further, this flexibility safeguards Hajj at the most pressured points, which could otherwise become treacherous. Despite this flexibility, Hajj stampedes have been recurring events, most notably at the Jamarat site.42

According to Islam, only adults should undertake the Hajj. The age at which Hajj is undertaken varies according to culture. Some nationalities seem to undertake Hajj at a uniformly young age (eg, Indonesian and Malaysian), whereas other nationalities defer Hajj until the late phase of life as a precursor to preparing for death. There might also be differences in sex distribution. Malaysia for instance has had a female dominated Hajj attendance for more than three decades.42

In keeping with the Islamic spirit of compassion, Muslims are enjoined to undertake Hajj only when adequately healthy. Despite this strong scriptural admonition, many Muslims insist on Hajj even when wheelchair bound. Special accommodations for wheelchairs are provided at the holy mosque despite the tremendous crowd densities. These channels are wide enough to admit wheelchairs and one person pushing the wheelchair and are divided into two lanes (one for each direction). Pilgrims who are not well are provided transport by the Ministry of Health ambulance to Hajj sites as needed so they can complete their pilgrimage.

Because of the Islamic belief that death during the Hajj has a beneficial outcome in the afterlife, a few sick pilgrims attend, hoping for death during the Hajj. Public health and religious officials do much to dissuade this belief, which is often tenacious. This cultural belief system affects care providers at Hajj, all of whom are Muslims (non-Muslims are not permitted to enter the holy sites). Anecdotally, this belief affects resuscitation efforts of those in cardiac arrest, which once initiated (if the patient reaches the emergency rescue services in time) are unlikely to be pursued if not immediately successful. A do-not-resuscitate status is often requested by pilgrims who can speak for themselves.51

Hajj itself has several qualities that aid public health security.52 Attendees must practise specific behaviours for their Hajj to be considered valid, and these requirements are strict and closely adhered to by both clerical and community leaders. Crime is strictly forbidden at Hajj and the risk of violent altercation is reduced because of the weapon-free, drug-free, and alcohol-free environment.42 Tobacco intake is also banned, curtailing the risk of inadvertent fire hazards. By contrast with some other MGs, sexual relations are not allowed during Hajj and male and female pilgrims are accommodated separately even when travelling as families, eliminating the risk of sexually transmitted disease.

This observant, penitent, and sober crowd engrossed in worship is thus likely to remain cooperative and coherent if sudden events demand rapid cooperation with authorities. Insurrection, rioting, disinhibited behaviour, or hooliganism of any kind does not arise even in these extraordinarily massive crowds. Pilgrims are urged to safeguard themselves or others at all times, aiding the infirm and assisting the fallen, behaviours that symbolise peaceful Islamic societies that enhance the public health security. The spirit of cooperation is central to a successful acceptance of the Hajj by Allah in the Islamic belief system and reduces the potential risk of disastrous events in such massive crowds.

Planning for the Hajj

Saudi Arabia's responsibility for the Hajj has affected the country's advanced health-care infrastructure and its multinational approach to public health. Although other jurisdictions have administered the Hajj, Saudi Arabia has invested in it. Within the immediate vicinity of the Hajj, there are 141 primary health-care centres and 24 hospitals with a total capacity of 4964 beds including 547 beds for critical care. The latest emergency management medical systems were installed in 136 health-care centres and staffed with 17 609 specialised personnel. More than 15 000 doctors and nurses provide services, all at no charge. This event requires the planning and coordination of all government sectors; as one Hajj ends, planning for the next begins. Infection and prevention strategies are reviewed, assessed, and revised every year. Coordination and planning requires the efforts of 24 supervising committees, all reporting to the Minister of Health. The preventive medicine committee oversees all key public health and preventive matters during the Hajj and supervises staff working at all ports of entry. Public health teams distributed throughout the Hajj site are the operational eyes and ears of the policy planners.

Sharing experience through global health diplomacy

In hosting the modern Hajj, Saudi Arabia has weathered a 20th century world war, global outbreaks due to newly emerging disease (including SARS and meningococcal meningitis W135), and regional conflicts. In this time, the country has acquired a unique, resilient expertise concerning Hajj-related public health. Important observations that are relevant to public health planners everywhere are part of this experience. One of the best examples of such cross-cultural translation has been in the preparation for Barack Obama's Presidential Inauguration and crowd management informed by the Hajj experience.

Yet the process of exchanging expertise is possibly even more instructive. Collaborative work on this scale shows the increasingly important global health diplomacy in which the Muslim world has an enormous part to play. First articulated by the US Health and Human Services Secretary Tommy Thompson, global health diplomacy usually includes the provision of a service by one nation to another.6 The USA's rebuilding of maternity hospitals in Afghanistan or the deployment of the ship USS Comfort to serve as a site for temporary clinics in Vietnamese coastal waters are two recent examples.53

As they struggled with the best responses to the global threat of pandemic influenza A H1N1, which coincided with the Hajj in 2009, colleagues at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Saudi Ministry of Health worked together to deploy one of the largest real-time mobile databasing systems, which was designed to detect disease in real time at any MG. Senator John Kerry discussed precisely this joint effort in a speech in Doha at the 2010 US-Islamic World Forum.54, 55 This international collaboration was realised only through both intense personal dedication and the confidence the agencies had in their people. Such collaboration strongly resonates with President Obama's renewed hopes for US engagement with the Muslim world, as articulated in his speech in Cairo, Egypt, in June, 2009.54

People who collaborate, write, and disseminate information internationally have long been aware of the latent value of such informal, positive exchange. In the flat world of medical academia, individuals have immediate and palpable effects. Fostering such professional dialogues are everyday (albeit unseen) acts of global health diplomacy. When investigators and physicians work in a shared space, unfettered by the global geopolitics, global health diplomacy becomes alive and vibrant. Hajj medicine, as part of the emerging specialty of MG medicine, provides an extraordinary platform.

Saudi Arabia's experience in international service through public health is substantial and is promoting the emergence of the formalised specialty of MG medicine. Hajj continues to provide insights into advanced and complex public health challenges, which are unlocked through collaborative exchange.56 Disease and suffering remain universal, even in the 21st century. Solving these challenges is relevant to humanity everywhere. Islamic scholars have long referred to Hajj as a metaphor for ideal societal behaviour.42 At the centre of these ideals is a unifying theme: collaboration.

Saudi Arabia's experience of Hajj medicine contains rapidly developing public health solutions to several global challenges. Multiagency and multinational approaches to public health challenges are likely to become major factors in the specialty of global health diplomacy, engaging societies globally, and drawing the west a little closer to the east.

Conclusions

In view of the global public health threats that might originate from MGs, medicine relevant to MGs has become an essential specialised, interdisciplinary branch of public health, particularly hybridised with global health response, travel medicine, and emergency or disaster planning.52 Agencies outside the realm of public health should be closely involved in MG medicine. In the operation and management of an MG, several sectors—health care, security, and public communications—need to know how to interface with public health services and resources quickly and effectively. Involving public health experts with the broader civic planning for any MG helps with parallel transparency in needs and expectations, ensuring that public health considerations are factored into the entire planning process instead of intruding too late in development, relegating public health security concerns to little more than ineffective afterthought. Delayed entry of these actors into the planning process can debilitate or completely disable adequate responses to potential diseases during MGs. Experts must educate civic planners about the values of early collaborative approaches to MGs for these reasons.

Conventional concepts of disease and crowd control do not adequately address the complexity of MGs. The need for MG health policies that are guided by sound evidence but anchored in experience shows the importance of calls for a new academic medical and science-based discipline. MGs have been associated with death and destruction—catastrophic stampedes, collapse of venues, crowd violence, and damage to political and commercial infrastructure, but little is known about the threats from MGs to the global health security. WHO has worked closely with international agencies to address such risks.57, 58, 59 MGs pose complex challenges that require a broad expertise and Saudi Arabia has the experience and infrastructure to provide unique expertise with respect to MGs.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We identified references for this Review by searching Medline and the National Health Service hospital search service for articles published in English from 1880 to August, 2011. Additional articles were identified through searches of extensive files belonging to the authors. Search terms used were “mass gathering”, “disease”, “pilgrimage”, “Hajj”, “outbreak”, “public health”, “prevention”, “travel”, or “modeling”. We reviewed the articles found during these searches and relevant references cited in the articles.

Contributors

ZAM and GMS co-wrote the text. Imperial powers and 19th century Hajj, Hajj culture, and most of the global health diplomacy sections were contributed by QAA. RS compiled the table.

Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Abdullah A Al Rabeeah, the Saudi Minister of Health, for his leadership and support for hosting The Lancet conference on MG Medicine: implications and opportunities for global health security, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, Oct 23–25, 2010, which generated the series of reviews.

Contributors

ZAM and GMS co-wrote the text. Imperial powers and 19th century Hajj, Hajj culture, and most of the global health diplomacy sections were contributed by QAA. RS compiled the table.

Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Arbon P, Bridgewater FHG, Smith C. Mass gathering medicine: a predictive model for patient presentation and transport rates. Prehosp Disast Med. 2001;16:109–116. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00025905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell JA, Barbera MD. Mass gathering medical care: a twenty-five year review. Prehosp Disast Med. 1997;12:72–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomasi L. From medieval pilgrimage to religious tourism: the social and cultural economics of piety. In: Swatos WH, Tomasi L, editors. Homo viator: from pilgrimage to religious tourism via the journey. Praeger; Westport, CT: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner V, Turner E. Il pellegrinaggio. Lecce; Argo: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Lancet A Mohamedan doctor on the Mecca pilgrimage. Lancet. 1895;146:49–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carringdon D. Kumbh Mela. New Scientist. Jan 25, 2001. http://www.newscientist.com/articleimages/dn360/1-kumbh-mela.html (accessed Nov 25, 2011).

- 7.BBC News Kumbh Mela pictured from space. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/1137833.stm (accessed Dec 2, 2011).

- 8.Banerjee B. Millions of Hindus wash away their sins. Jan 15, 2007. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/-2007/01/15/AR2007011500041.html (accessed Dec 6, 2011).

- 9.BBC News Five die in stampede at Hindu Bathing festival. April 14, 2010. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/8619088.stm (accessed Dec 6, 2011).

- 10.Hinduism Today . Kumbh Mela –timeline. What is Hinduism?: Modern adventures into a profound global faith. Himalayan Academy Publications; Kapaa, HI: 2007. pp. 242–243. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hays JN. Epidemics and pandemics: their impacts on human history. ABC-CLIO; Santa Barbara, CA: 2005. pp. 214–219. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wikipedia Cholera outbreaks and pandemics. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cholera_outbreaks_and_pandemics (accessed Nov 20, 2011).

- 13.Ayyagari A, Bhargava A, Agarwal R. Use of telemedicine in evading cholera outbreak in Mahakumbh Mela, Prayag, UP, India: an encouraging experience. Telemed J E Health. 2003;9:89–94. doi: 10.1089/153056203763317693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanctuaires Notre-Dame de Lourdes In the baths. http://www.lourdes-france.org/index.php?goto_centre=ru&contexte=en&id=434 (accessed Dec 05, 2011).

- 15.Harris R. Lourdes: body and spirit in the secular age. Penguin Books; London: 1999. p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Indian Express Another Black Friday for Sabarimala pilgrims. Jan 15, 2011. http://www.indianexpress.com/news/another-black-friday-for-sabarimla-pilgrims/737807/ (accessed Dec 6, 2011).

- 17.The Hindu Sabarimala stampede death toll crosses 100. http://www.thehindu.com/news/states/kerala/article1094519.ece (accessed Nov 20, 2011).

- 18.Times of India 104 killed in Sabarimala stampede, 50 injured. Jan 15, 2011. http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2011-01-15/india/28352194_1_sabarimala-stampede-pulmedu-vandiperiyar (accessed Dec 6, 2011).

- 19.Wikipedia Black Nazarene. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Nazarene (accessed Nov 20, 2011).

- 20.Wikipedia List of largest peaceful gatherings in history. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_largest_peaceful_gatherings_in_history (accessed June 20, 2011).

- 21.ProMED Mail Measles–Canada: (BC), imported. http://www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=20100406.1102 (accessed Nov 20, 2011).

- 22.ProMED Mail Varicella, Asian Games–Qatar ex Maldives. http://www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=20061129.3385 (accessed Nov 20, 2011).

- 23.Wikipedia Centennial Olympic Park bombing. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Centennial_Olympic_Park_bombing (accessed Nov 18, 2011).

- 24.Wikipedia 1972 Summer Olympics. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1972_Summer_Olympics (accessed Nov 18, 2011).

- 25.Fordham University Medieval Sourcebook, Procopius: Justinian suppresses the Nika revolt, 532. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/procop-wars1.asp (accessed Nov 18, 2011).

- 26.New York Times Golden Gate crowd made bridge bend. http://www.nytimes.com/1987/05/26/us/golden-gate-crowd-made-bridge-bend.html?scp=1&sq=&st=nyt (accessed Nov 18, 2011).

- 27.Armstrong K. Muhammad: a biography of the Prophet. Harper Collins; San Francisco, CA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Lancet Return pilgrims from Mecca. Egyptian quarantine at Torr. (From a correspondent) Lancet. 1893;142:409–410. [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Lancet Pilgrims at Mecca. Lancet. 1881;117:105. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corbyn EN. The pilgrimage to Mecca: medical care of pilgrims from the Sudan. Lancet. 1945;246:445. [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Lancet The origin of cholera in Mecca. Lancet. 1895;145:1327. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mackie J. Cholera at Mecca and quarantine in Egypt. Lancet. 1893;142:1054–1056. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.1700.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Lancet The risks of the Mecca pilgrimage. Lancet. 1923;202:576–577. [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Lancet The Mecca pilgrimage. Lancet. 1929;214:1237. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Donkin H, Thiselton Dyer WT, Frankland E, Enfield The Cholera and Hagar's Well at Mecca. Lancet. 1883;122:256–257. [Google Scholar]

- 36.The Lancet Hagar's Well at Mecca. Lancet. 1884;123:33–34. [Google Scholar]

- 37.The Lancet Camaran: the cause of Cholera to Mecca pilgrims. Lancet. 1895;146:1519. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roff WR. Sanitation and security: the imperial powers and the nineteenth century Hajj. Arabian Stud. 1982;6:143–160. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watson GJ. Mecca pilgrimage quarantine and the Mecca pilgrimage–the growth of an idea. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1938;32:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- 40.The Lancet A medico-sanitary pilgrimage to Mecca. Lancet. 1880;115:619–620. [Google Scholar]

- 41.The Lancet The pilgrimage to Mecca. Lancet. 1935;226:1473. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bianchi RR. Guests of God pilgrimage and politics in the Islamic world. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Memish ZA, Ebrahim S, Denning M, Ahmed Q, Assiri A. Pandemic H1N1 influenza at the 2009 Hajj: understanding the unexpectedly low H1N1 burden. J Royal College of Med J R Soc Med. 2010;103:386. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2010.100263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khan K, Memish ZA, Chabbra A. Global public health implications of a mass gathering in Mecca, Saudi Arabia during the midst of an influenza pandemic. J Travel Med. 2010;17:75–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Almazroa M, Memish ZA, Alwadey AM. Influenza A (H1N1) in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: description of the first one hundred cases. Annals Saudi Med. 2010;30:11–14. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.59366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Memish ZA, McNabb SJN, Mahoney F, and the Jeddah Hajj Consultancy Group Establishment of public health security in Saudi Arabia for the 2009 Hajj in response to pandemic influenza A H1N1. Lancet. 2009;374:1786–1791. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61927-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ebrahim S, Memish ZA, Khoja T, Uyeki T, Marano N, Mcnabb S. Pandemic H1N1 and the 2009 Hajj. Science. 2009;326:938–940. doi: 10.1126/science.1183210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.WHO Health conditions for travellers to Saudi Arabia for the pilgrimage to Mecca (Hajj). Transmission dynamics and impact of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009;84:477–484. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia 2,521,000 million pilgrims participated in Hajj 1430. Nov 29, 2009. http://www.saudiembassy.net/latest_news/news11290904.aspx (accessed Aug 30, 2010).

- 50.Kamran K, Memish Z, Aneesh C, Liauw J. Global Public Health Implications of a Mass Gathering in Mecca, Saudi Arabia During the Midst of an Influenza Pandemic. J Travel Med. 2010;17:75–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arabi YM, Alhamid SM. Emergency room to the intensive care unit in Hajj. The chain of life. Saudi Med J. 2006;27:937–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahmed Q, Barbechi M, Memish ZA. The quest for public health security at Hajj: the WHO guidelines on communicable disease alert and response during mass gatherings. Travel Med Infect Dis J. 2009;7:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iglehart JK. Advocating for medical diplomacy: a conversation with Tommy G Thompson. http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/early/2004/05/04/hlthaff.w4.262.citation?related-urls=yes&legid=healthaff;hlthaff.w4.262v1&cited-by=yes&legid=healthaff;hlthaff.w4.262v1 (accessed Nov 25, 2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, June 4, 2009. Remarks by the President on a new beginning. www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/Remarks-by-the-President-at-Cairo-University-6-04-09/ (accessed Oct 5, 2009).

- 55.US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Chairman Kerry addresses the US-Islamic World Forum. http://foreign.senate.gov/press/chair/release/?id=904d1509-53cd-4112-a15e-72feebc26fcb (accessed Aug 18, 2011).

- 56.Memish ZA, Alrabeeah AA. Jeddah declaration on mass gatherings health. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:342–343. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.WHO International health regulations. 2005. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241580410_eng.pdf (accessed Nov 18,2011).

- 58.WHO Communicable disease alert and response for mass gatherings: key considerations. http://www.who.int/csr/mass_gathering/en/ (accessed Nov 18, 2011).

- 59.WHO. Global forum on mass gatherings 2009, Rome Italy. WHO/HSE/GAR/SIH_2011.1/eng.pdf (accessed Nov 18, 2011).