Abstract

Background

Scirrhous gastric cancer is associated with peritoneal dissemination and advanced lymph node metastasis from an early stage, and the prognosis is still poor. In this study, we aimed to analyze candidate molecules for targeted therapy of scirrhous gastric cancer. We searched for molecules/metabolic activity that might be predominantly expressed in a subpopulation of scirrhous gastric cancer cells and might function as cancer stem cell markers.

Results

For this purpose, we investigated the expression of various cell surface markers and of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity. These analyses showed that the scirrhous gastric cancer cell lines HSC-58 and HSC-44PE heterogeneously expressed CD13, while CD44, CDCP1, EpCAM and ABCG2 were expressed uniformly. Moreover, 10% of the total HSC-58 cell population expressed ALDH enzyme activity. A subpopulation of cells strongly positive for ALDH also expressed high levels of CD13, both of which are known as cancer stem cell markers. HSC-58 cells expressing high levels of CD13 showed lower sensitivity to a cancer drug cisplatin than cells with low levels of CD13. In contrast, CD13-high subpopulation of HSC-58 was more sensitive to an aminopeptidase N inhibitor bestatin. In terms of antibody-drug therapy, anti-CD13-immunotoxin was highly cytotoxic towards HSC-58 cells and was more cytotoxic than anti-EpCAM-immunotoxin.

Conclusion

These data suggest that CD13 is a suitable cell surface candidate for targeted antibody-drug therapy of scirrhous gastric cancer.

Introduction

Although the prevalence of gastric carcinoma has recently shown a gradual decrease, this cancer still accounts for a significant proportion of cancer-related deaths in Japan. Early detection and prevention of metastasis of this cancer is essential in order to improve the cure rate. Scirrhous gastric cancer, known as diffusely infiltrative carcinoma, Borrmann's type-IV carcinoma, or linitis plastica-type carcinoma, is characterized clinically as having the worst prognosis among the various types of gastric cancer, because it is frequently associated with metastases to lymph nodes and peritoneal dissemination. Scirrhous gastric cancer, which represents approximately 10% of gastric carcinomas, shows a 5-year survival rate of less than 17%, compared with 35 to 70% for other types of gastric cancers [1]. Various treatments, such as chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, hyperthermia, and immunotherapy have been tested for effectiveness against peritoneal metastasis from scirrhous gastric cancer, but the results have been unsatisfactory [2]. Chemotherapy plays a significant role in the treatment of such gastric cancer. However, the prognosis of advanced gastric cancer is still poor and treatment is usually unsuccessful. There is therefore an urgent need for development of an effective treatment for such patients.

Stem cells constitute the source of cell populations in the tissues of each organ and exhibit self-renewal ability and multi-differentiation potential. In the case of cancer, a subpopulation of cancer cells that exhibit the properties of stem cells are also present in cancer tissues. These so-called cancer stem cells (CSCs) were first reported in acute leukemia [3], and it later became clear that CSCs are also present in solid tumors such as breast cancer and brain tumors [4], [5]. CSCs have been proposed to be the root cause of cancer growth and to be drug-resistant. Attempts to identify CSCs have been made based on their expression of cell surface molecules or on their intracellular metabolic activity, by analysis of both primary tumor specimens and established cell lines. Currently, there are reports of definitive CSC markers in digestive cancers such as colorectal cancer, liver cancer, and pancreatic cancer [6], [7], [8]. Among various cell surface markers for the identification of CSCs, Haraguchi et al. identified CD13 as functional marker that can be used to identify potentially dormant liver CSCs [9]. However, there have been few clear definitive CSC markers in upper gastrointestinal cancers such as in esophagus or stomach cancers.

The first aim of this study was therefore to determine the contribution of CD13 in scirrhous gastric cancer cell lines. We analyzed these cells for CD13 and other cell surface antigens and metabolic enzyme activity that were considered as possible candidate CSC markers by using flow cytometry [10]. The second aim of this study was to assess whether antibody-mediated drug/toxin conjugates (immunotoxins) targeted towards CD13 on scirrhous gastric cancers, would show enhanced antitumor effect against scirrhous gastric cancer.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and cell culture

The scirrhous gastric cancer cell lines HSC-58, HSC-44PE, 58As1 and 44As3 were previously established from the ascitic fluid of patients with scirrhous gastric carcinoma [11]. The stomach adenocarcinoma MKN-7, MKN-45 and signet-ring cell carcinoma KATO-III were obtained from JCRB Cell Bank (Osaka, Japan) [12]. These cells were maintained in RPMI1640 medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco Life Technologies; Grand Island, NY), antibiotics and sodium pyruvate (Gibco). The cultures were maintained at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air, and were propagated as low adhesion cultures at the bottom of plastic dishes.

Flow cytometric analysis

The following antibodies were used for flow cytometric analysis of cells: anti-CD24-FITC, anti-CD44-FITC, anti-CD90-FITC, anti-CD133-PE, anti-MDR1-PE, anti-EpCAM-PE, anti-CD13-PE (all from eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and anti-CDCP1-FITC and anti-ABCG2-PE (both from BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Cells were incubated with the indicated antibodies for 60 min and were then washed twice with PBS containing 2% FCS. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using a FACS-Calibur (BD Immunocytometry Systems, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Aldehyde dehydrogenase assay

Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity in the cancer cells was assayed using the ALDEFLUOR® substrate according to the manufacturer's protocol (StemCell technologies, Vancouver, Canada). Specimens that were analyzed for ALDH activity were counter-stained with anti-CD13-PE at the appropriate dilution. Non-viable cells were eliminated using propidium iodide (Sigma). The specific flow gates for ALDH positive cells were set using a control sample of the isolated tumor cells in which ALDH activity was inhibited with diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB). Subsequent flow cytometry runs were used to identify populations of cells with high ALDH activity (ALDH-high) and those that expressed the surface marker CD13 (aminopeptidase N; APN) (CD13+).

Magnetic cell sorting and cancer drug sensitivity of HSC-58 cells

For the separation of HSC-58 cells with various cell surface levels of CD13, cell suspensions of HSC-58 were incubated with purified anti-CD13 antibody (low-endotoxin, azide-free, BioLegend) and microbeads with bound anti-mouse IgG (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) on ice for 1 hour. After washing with PBS, cells were placed in an AutoMACS cell separator (Miltenyi Biotech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells with high or low levels of CD13 were sorted and collected separately, and sorted cells were washed and resuspended. To test cancer drug sensitivity, the cells were plated into a 96-well flat microplate at 4 × 104 cells/well. A two-fold dilution series of cisplatin (CDDP, initial concentration; 1.0 μg/mL) and four-fold dilution series of bestatin (ubenimex, initial concentration; 5.0 μg/mL) were made, and the cells were cultured in the indicated concentrations of drugs at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 5 days. Viable cells were counted after staining with the AlamarBlue® reagent (AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK). Data were analyzed and represented by using GraphPad Prism software ver. 4.0.

Targeted delivery of immunotoxin into HSC-58 cells

HSC-58 cells were seeded at a density of 5000 cells/well in 96-well culture plates. Cells were incubated with anti-CD13, anti-EpCAM or isotype control IgG (1 μg/mL for all) and subsequently saporin-conjugated anti-mouse IgG Ab (MAb-ZAP, Advanced Targeting Systems, San Diego, CA) was added at a concentration that varied from 37 to 500 ng/mL. Cell viability was determined after 5 days using the AlamarBlue® reagent.

Results

Heterogeneous expression of CD13 in scirrhous gastric cancer HSC-58 cells

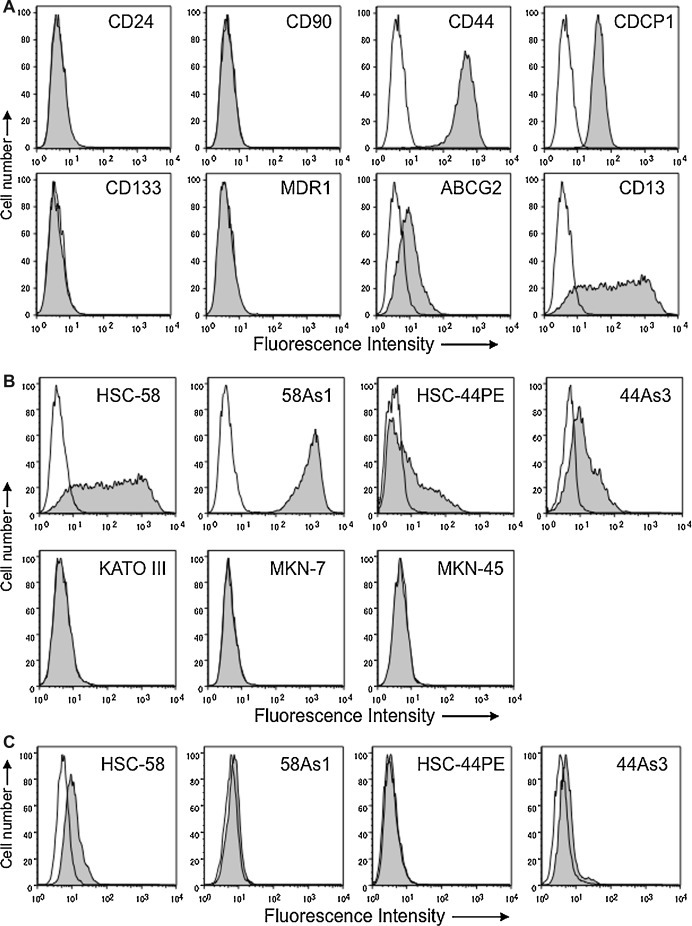

We first examined HSC-58 cells for the expression of various cell surface molecules including CD44, CD90, CD133, CDCP1, MDR1, ABCG2, CD13 and CD24 that were previously reported as CSC markers by others [13], [14], [15]. As shown in Fig. 1 A, there was absolutely no expression of CD90, CD133, MDR1 or CD24 in the HSC-58 cells, but CDCP1, ABCG2 and CD44 were uniformly positive. In contrast, only CD13 showed heterogeneous expression in HSC-58. We next examined the expression of CD13 on various human gastric scirrhous and adenocarcinoma cell lines (Fig. 1B). We found that CD13 was expressed on scirrhous gastric cell lines (HSC-58, 58As1, HSC-44PE and 44As3) but not on well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma cell line MKN-7 and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma cell line MKN-45. The KATO-III derived from signet-ring cell carcinoma was also negative for CD13. Interestingly, highly metastatic cell lines 58As1 and 44As3 isolated from HSC-58 and HSC-44PE, respectively, were strongly positive for CD13.

Figure 1.

Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of various cell surface molecules on human scirrhous and adenocarcinoma gastric cancer cell lines. A. Expression of CD24, CD90, CD44 and CDCP1 (upper panels) and CD133, MDR1, ABCG2, and CD13 (lower panels) on scirrhous gastric cancer HSC-58 are analyzed by flow cytometry and shown as histograms. Open histograms indicate the cells stained with mouse isotype control IgG1. And shaded histograms show the cells stained with various antibodies as indicated. B. Expression of CD13 on gastric cancer cell lines, HSC-58, 58As1, HSC-44PE and 44As3 (scirrhous cancers; upper panels) and KATO-III, MKN-7 and MKN-45 (adenocarcinomas; lower panels). C. Expression of ABCG2 on scirrhous gastric cancer cell lines are shown as histograms.

Several studies reported that ABCG2 is a more reliable cell surface marker to identify CSCs [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], we then examined whether ABCG2 would be useful for the identification of CSCs in scirrhous gastric cancers. However, ABCG2 expressed weakly only on HSC-58 and 44As3 but not on HSC-44PE and 58As1 (Fig. 1C). These results suggested that CD13 might be useful as a certain subpopulation of scirrhous gastric cancer cells.

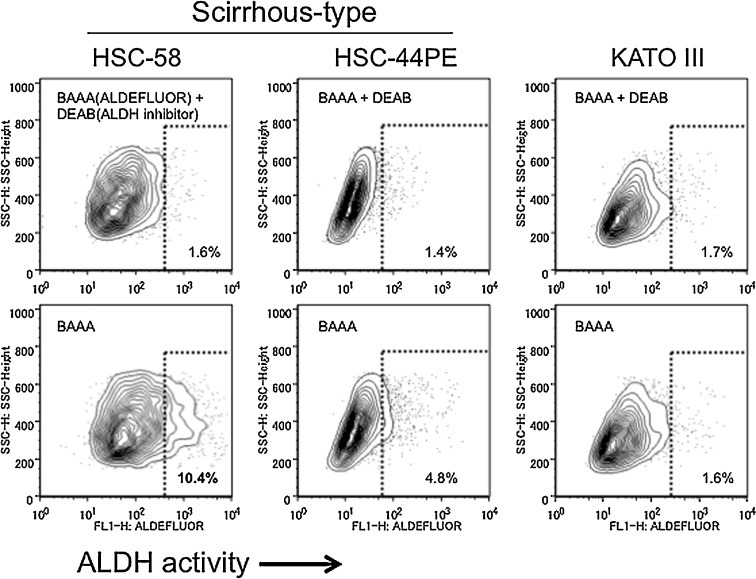

Aldehyde dehydrogenase activity in HSC-58 cells

Cell populations highly expressed ALDH were previously reported to be considered to have characteristics of CSCs in gastric cancers [21], [22]. We next examined ALDH expression in two different scirrhous gastric cancer cell lines (HSC-58 and HSC-44PE) and KATO-III, using flow cytometry. We found that 10.4% of HSC-58 cells expressed ALDH, whereas 4.8% and 1.6% of HSC-44PE and KATO-III cells, respectively expressed ALDH (Fig. 2 ). These data supported ALDH expression as a marker for identification of CSCs in HSC-58 cells.

Figure 2.

Characterization of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity and CD13 expression of HSC-58 cells. ALDH expression was assayed in the human gastric cancer cell lines HSC-58 (left panels) and HSC-44PE (middle panels), and in the stomach signet-ring cell carcinoma cell line KATO-III (right panels) by staining with the ALDH substrate ALDEFLUOR® (BAAA; BODIPY® aminoacetaldehyde) in the presence or absence of the ALDH inhibitor diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB), followed by FACs analysis. Horizontal and vertical axes denote expression intensity.

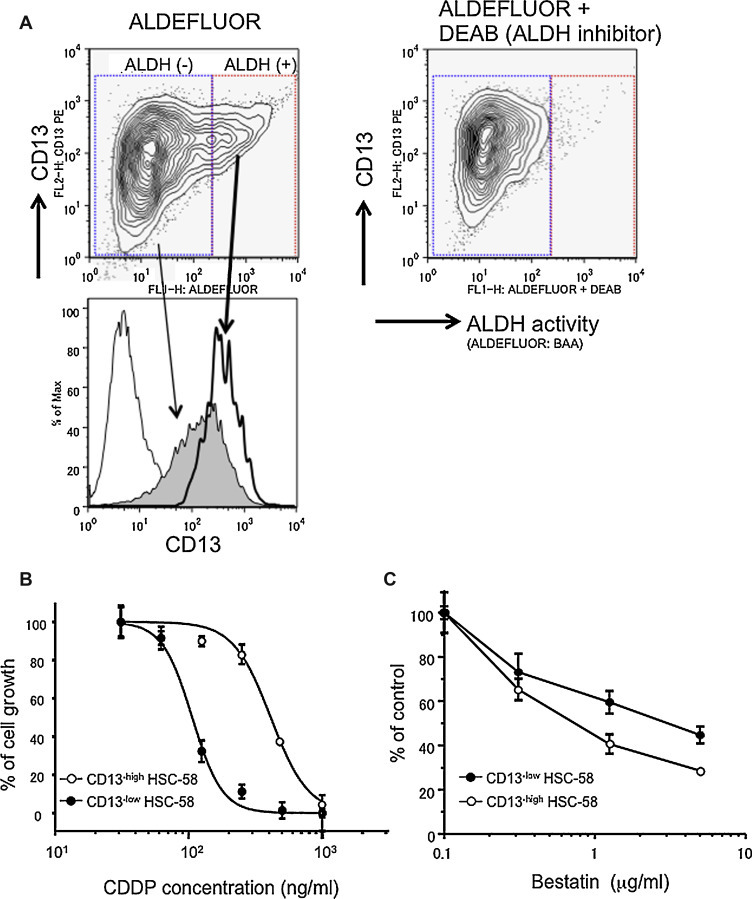

Chemosensitivity of CD13high cell population of HSC-58 cells

We then investigated whether a population of HSC-58 cells that express high ALDH activity could also express any of the cell surface CSC candidates identified above. HSC-58 cells were evaluated by flow cytometry using a fluorescent substrate for assay of ALDH activity and using PE-conjugated antibodies against cell surface molecules such as CD44, ABCG2 and CD13 [4], [9], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. The population of cells that was strongly positive for ALDH also expressed high levels of CD13 (Fig. 3 A), but no correlation was found between ALDH activity levels and CD44 or ABCG2 levels (data not shown). We then investigated the drug sensitivity of CD13high and CD13low subpopulations of HSC-58 cells by analysis of the growth inhibitory effect of different concentrations of cisplatin, which is widely used clinically as an anticancer agent. As shown in Fig. 3B, the CD13high HSC-58 subpopulation showed lower sensitivity to cisplatin (CI50; 411 ng/mL) than the CD13low cells (CI50; 106 ng/mL). In order to confirm the contribution of CD13 in drug resistance of scirrhous cancer cell lines, we tested the inhibitory effect of APN/CD13 inhibitor, bestatin, on the growth of HSC-58. As shown in Fig. 3C, the CD13high HSC-58 subpopulation showed higher sensitivity to bestatin than the CD13low cells. These results may support that a drug-resistant property of cancer cells might be correlated with high levels of CD13.

Figure 3.

ALDH activity and CD13 expression of HSC-58 cells. A. HSC-58 cells were analyzed for ALDH activity as in the legend of Fig. 2, and were also analyzed by FACS for CD13 expression. Horizontal axes denote the expression intensity of ALDH activity, the vertical axes denote CD13 expression (upper panels). The shaded histogram indicates CD13 expressing cells with low ALDH activity. The open histogram (thick line) indicates CD13 expressing cells with high ALDH activity. B, C. Drug sensitivity test of HSC-58 cells sorted into CD13-high (open circles) and CD13-low populations (closed circles). HSC-58 cells were separated by AutoMACS and sorted cells are exposed to the indicated concentrations of cisplatin (B) or bestatin (C) for 5 days following which viable cells were counted by fluorescence analysis of reduction of the AlamarBlue® reagent. Data are analyzed and represented by GraphPad Prism ver. 4.0 software.

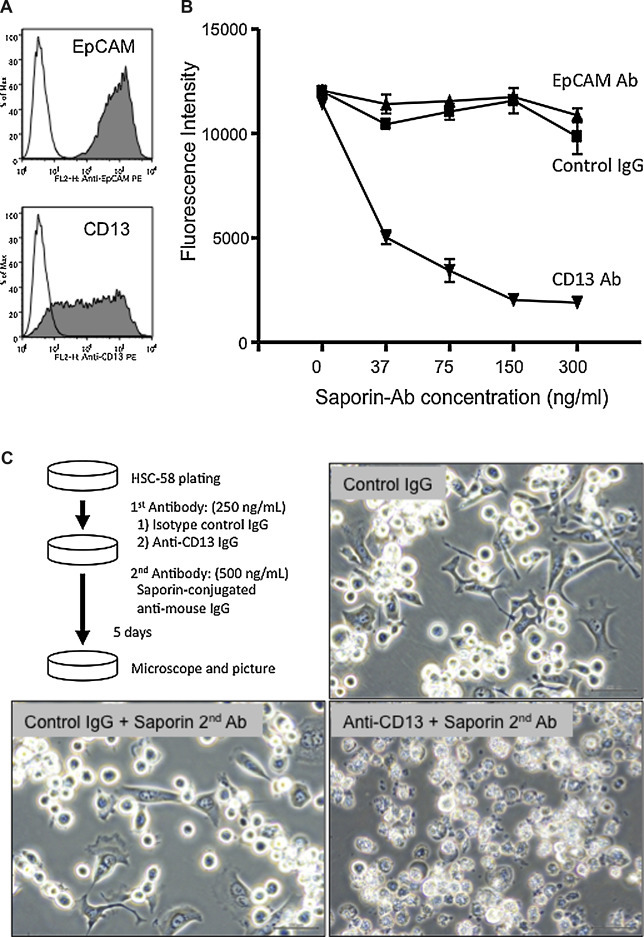

CD13 targeted immunotoxin

For further investigation of the potential ability of CD13 to internalize toxic drugs in HSC-58 cells, we next examined the cytotoxicity of antibody drug conjugates targeted against CD13 or EpCAM Ab on HSC-58 cells. Prior to these experiments, we confirmed the expression of EpCAM and CD13 by flow cytometry (Fig. 4 A). As shown in Fig. 4B and C, the saporin-conjugated second antibody was cytotoxic towards HSC-58 cells that had bound anti-CD13 Ab, in a saporin-conjugated antibody dose-dependent manner. However, the saporin-conjugated second antibody was not cytotoxic towards HSC-58 cells to which the anti-EpCAM Ab was bound. These data show that CD13 is a suitable cell surface candidate for targeted antibody-drug therapy of scirrhous gastric cancer.

Figure 4.

Targeted delivery of an immunotoxin into HSC-58 cells. A. Expression of CD13 and EpCAM on HSC-58 cells as analyzed by flow cytometry. B. Cytotoxicity of a saporin-conjugated second antibody targeted against anti-CD13, anti-EpCAM antibody or control IgG bound to HSC-58 cells was assayed using fluorescence analysis of reduction of the dye AlamarBlue®. The horizontal axis denotes the concentration of the saporin immunotoxin. The vertical axis indicates cell survival. C. Phase-contrast images of representative cells treated with isotype control IgG (negative control; top right), isotype control IgG plus saporin-conjugated second antibody (bottom left) and anti-CD13 IgG plus saporin-conjugated second antibody (bottom right) for 5 days.

Discussion

Numerous reports have shown that a small subset of cancer cells bears drug-resistance and stem cell properties and that these cells are referred to as cancer stem or stem-like cells (CSCs), or as tumor-initiating cells (TICs). CSC identification was first attempted in acute leukemia, and was then later attempted for many types of cancers, however, no CSCs have been validated in scirrhous gastric cancer cell lines. Li et al. reported that CSCs could be identified in pancreatic cancers based on the high expression of CD44, CD24 and ESA on their cell surface [8]. Other studies have shown that CD133 is a marker for CSCs of breast, colon, lung, ovary, pancreas and prostate cancers [6], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]. In addition to these markers, overexpression of cell surface transport proteins including MDR-1 and ABCG2 are related to the multidrug-resistance property of CSCs [28], [29]. We therefore tried to identify CSCs in the scirrhous gastric cancer cell line HSC-58 using antibodies against various cell surface CD antigens such as CD24, CD44, CD90, CD133, CDCP1, CD13, ABCG2 and MDR-1, using flow cytometry. Unexpectedly, most of these cell surface markers were either not expressed or were uniformly expressed, except for CD13 that was heterogeneously expressed. The heterogeneous expression of CD13 was also found in HSC-58 and HSC-44PE cells. Interestingly, highly metastatic cell line 58As1 (derived from parental HSC-58) caused fatal cancerous peritonitis and bloody ascites expressed extremely high levels of CD13. In contrast, KATO-III with weak tumorigenicity in nude mice lacked the expression of CD13. It is anticipated that tumorigenic properties of scirrhous gastric cancer cell lines might be related with the CD13high population.

Another commonly-used cancer and normal hematopoietic stem cell marker is ALDH, which is an intracellular enzyme that is involved not only in retinoic acid and ethanol metabolism but also in resistance to alkylating cancer drugs [30]. It has been shown that high ALDH expression correlates with tumorigenic potential and poor prognosis in breast cancer patients [10]. We therefore determined expression of the metabolic marker ALDH in HSC-58 cells. Previous reports have shown that expression of CD44, or of an alternatively spliced variant of CD44 (CD44R), and of ABCG2 strongly contribute to cellular resistance against various anticancer drugs [31], [32]. Based on our data, it is unlikely that ALDH activity is correlated with the expression of these cell surface molecules in the scirrhous gastric cancer cell line HSC-58. However, we observed that approximately 10% of the HSC-58 cells expressed high levels of ALDH activity. This cell population that was enriched for ALDH activity was almost identical to the CD13high population. A significantly greater number of the CD13high and ALDHhigh cell population of HSC-58 survived chemotherapy with CDDP relative to the CD13low and ALDHlow cell population. In our preliminary data, CD13 expression on HSC-58 cells was increased by treatment with anticancer agents including doxorubicin and decitabine (data not shown). These data suggest that CD13 is one of candidates that can be used as a marker to enrich a cell population containing putative CSCs.

CD13 is an abundant myeloid differentiation antigen that is also expressed on non-hematopoietic cells. Several reports have shown a relationship between CD13 and cancer [9], [33]. CD13 is thought to play an important role in protein digestion and also to decompose type-4 collagen and confer an extra-cellular matrix metastasizing ability on tumor cells. Moreover, CD13 is expressed by endothelial cells in the process of neovascularization and can contribute to enhancement of tumor metastasis and invasion, indicating that CD13 expression is a candidate for contribution to the poor prognosis of cancers [34], [35]. Indeed, some inhibitors with CD13-inhibiting properties have entered anticancer clinical trials. Thus, Bestatin (ubenimex), which was originally described as an immunomodulant, inhibits aminopeptidase activity, and several clinical trials targeted towards hematological malignancies have been conducted with this agent. A survival benefit of ubenimex has been demonstrated in acute myeloid leukemia and lymphomas [36]. Additionally, various clinical studies have been conducted with ubenimex in non-hematopoietic cancers such as lung, bladder, head and neck, esophagus and skin [37]. As shown in Fig. 3C, bestatin exhibited antiproliferative effect of HSC-58 cells in vitro and CD13high cell population of HSC-58 was more sensitive to bestatin than CD13low HSC-58 cells. Furthermore, curcumin is a natural phenolic product isolated from turmeric that has been reported to inhibit CD13 [38]. The inhibition of CD13 by curcumin is greater than that by bestatin, consequently curcumin is currently being investigated for its effect on patients with breast, prostate and pancreatic cancer [39], [40], [41], [42]. These results indicate that CD13 is associated with cell growth, invasion and metastasis of various cancers and suggest that CD13 is a suitable target for anticancer therapy.

Antibody targeting of cell surface molecules that are overexpressed in cancer cells compared to normal cells is effective for cancer therapy. Currently, more than 30 therapeutic monoclonal antibodies have been approved for clinical applications against cancers [43], [44]. Novel strategies of conjugation of drugs or radioactive agents to such antibodies are particularly promising therapeutic approaches. Several drug-conjugated antibodies specific for CD33, CD20, HER2 and CD22 are currently being tested in clinical trials [45], [46]. However, not all antibodies that bind to cell surface molecules are suitable for use as therapeutic drug conjugates. This is because, in order for delivery of the drug/cytotoxic agent that is bound to the antibody into the cells, it is essential that the drug-conjugated antibody be internalized together with the cytotoxic agent into the cancer cells. There has so far been no investigation regarding the usefulness of CD13 for drug-conjugated antibody therapy. In order to investigate this possibility, we analyzed the cytotoxicity of immunotoxin (saporin) conjugated anti-CD13 antibody treatment of HSC-58 cells in vitro. As shown in Fig. 4, the efficiency of in vitro toxin delivery into HSC-58 cells was higher for anti-CD13 antibody in combination with saporin-conjugated anti-mouse IgG than for the control IgG, and its efficacy increased in a saporin-conjugated antibody dose-dependent manner. As compared with anti-CD13/APN inhibitors such as bestatin and curcumin, the advantage of anti-CD13 antibody conjugate therapy is more specific and effective against scirrhous gastric cancer HSC-58.

The efficacy of the anti-CD13 antibody for toxin delivery is in contrast to that of the anti-EpCAM antibody. Thus, although EpCAM is highly expressed in HSC-58 cells, improvement of toxin delivery compared to control IgG using the anti-EpCAM antibody is quite low. Low efficiency of EpCAM-targeted immunotoxin might be due to the lack of internalization property of anti-EpCAM antibody. The higher efficacy of the anti-CD13 antibody may be due to the fact that CD13 has been characterized as a cellular receptor for coronavirus and cytomegalovirus infection, indicating that CD13 can efficiently deliver the virus protein into the cells [47]. The antibody to CD13 can function as an artificial ligand that can mimic a natural viral CD13 ligand against both CD13high and CD13low cell population of HSC-58 cells, indicating that anti-CD13 antibody-mediated intracellular delivery of immunotoxin may be therapeutically effective against scirrhous gastric cancer. We are also planning to investigate the therapeutic effect of anti-CD13 immunoliposome containing curcumin against scirrhous gastric cancer xenograft.

In conclusion, the data of this study suggest the possibility that a certain cell population of scirrhous gastric cancers with drug-resistance express CD13 that it may also function as a target for cancer therapy. However, further investigation is needed to clarify the contribution of CD13 to CSC function and to corroborate the role of CD13 in drug-resistance or tumor activity by analysis of clinical specimens of scirrhous gastric cancers.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ritsuko Harigai and Noriyuki Ohmori for performing cell culture, flow cytometry, cell sorting and chemosensitivity assay. This research was supported in part by grant-in-aid for Scientific Research “B” (grant no. 25293133) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

References

- 1.Yashiro M., Hirakawa K. Cancer-stromal interactions in scirrhous gastric carcinoma. Cancer Microenviron. 2010;3:127–135. doi: 10.1007/s12307-010-0036-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitamura K., Beppu R., Anai H., Ikejiri K., Yakabe S., Sugimachi K., et al. Clinicopathologic study of patients with Borrmann type IV gastric carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 1995;58:112–117. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930580208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonnet D., Dick J.E. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Hajj M., Wicha M.S., Benito-Hernandez A., Morrison S.J., Clarke M.F. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh S.K., Hawkins C., Clarke I.D., Squire J.A., Bayani J., Hide T., et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ricci-Vitiani L., Lombardi D.G., Pilozzi E., Biffoni M., Todaro M., Peschle C., et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007;445:111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma S., Chan K.W., Hu L., Lee T.K., Wo J.Y., Ng I.O., et al. Identification and characterization of tumorigenic liver cancer stem/progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2542–2556. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li C., Heidt D.G., Dalerba P., Burant C.F., Zhang L., Adsay V., et al. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1030–1037. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haraguchi N., Ishii H., Mimori K., Tanaka F., Ohkuma M., Kim H.M., et al. CD13 is a therapeutic target in human liver cancer stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3326–3339. doi: 10.1172/JCI42550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ginestier C., Hur M.H., Charafe-Jauffret E., Monville F., Dutcher J., Brown M., et al. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:555–567. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yanagihara K., Tanaka H., Takigahira M., Ino Y., Yamaguchi Y., Toge T., et al. Establishment of two cell lines from human gastric scirrhous carcinoma that possess the potential to metastasize spontaneously in nude mice. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:575–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb02489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motoyama T., Hojo H., Watanabe H. Comparison of seven cell lines derived from human gastric carcinomas. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1986;36:65–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1986.tb01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rocco A., Liguori E., Pirozzi G., Tirino V., Compare D., Franco R., et al. CD133 and CD44 cell surface markers do not identify cancer stem cells in primary human gastric tumors. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:2686–2693. doi: 10.1002/jcp.23013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buhring H.J., Kuci S., Conze T., Rathke G., Bartolovic K., Grunebach F., et al. CDCP1 identifies a broad spectrum of normal and malignant stem/progenitor cell subsets of hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic origin. Stem Cells. 2004;22:334–343. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-3-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keshet G.I., Goldstein I., Itzhaki O., Cesarkas K., Shenhav L., Yakirevitch A., et al. MDR1 expression identifies human melanoma stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;368:930–936. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou S., Schuetz J.D., Bunting K.D., Colapietro A.M., Sampath J., Morris J.J., et al. The ABC transporter Bcrp1/ABCG2 is expressed in a wide variety of stem cells and is a molecular determinant of the side-population phenotype. Nat Med. 2001;7:1028–1034. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Britton K.M., Eyre R., Harvey I.J., Stemke-Hale K., Browell D., Lennard T.W., et al. Breast cancer, side population cells and ABCG2 expression. Cancer Lett. 2012;323:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leccia F., Del Vecchio L., Mariotti E., Di Noto R., Morel A.P., Puisieux A., et al. ABCG2, a novel antigen to sort luminal progenitors of BRCA1- breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:213. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang G., Wang Z., Luo W., Jiao H., Wu J., Jiang C. Expression of potential cancer stem cell marker ABCG2 is associated with malignant behaviors of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:782581. doi: 10.1155/2013/782581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbott B.L. ABCG2 (BCRP) expression in normal and malignant hematopoietic cells. Hemat Oncol. 2003;21:115–130. doi: 10.1002/hon.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen W., Zhang X., Chu C., Cheung W.L., Ng L., Lam S., et al. Identification of CD44+ cancer stem cells in human gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:949–954. doi: 10.5754/hge12881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishikawa S., Konno M., Hamabe A., Hasegawa S., Kano Y., Ohta K., et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase high gastric cancer stem cells are resistant to chemotherapy. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:1437–1442. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Q., Li J.G., Zheng X.Y., Jin F., Dong H.T. Expression of CD133, PAX2, ESA, and GPR30 in invasive ductal breast carcinomas. Chin Med J. 2009;122:2763–2769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eramo A., Lotti F., Sette G., Pilozzi E., Biffoni M., Di Virgilio A., et al. Identification and expansion of the tumorigenic lung cancer stem cell population. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:504–514. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curley M.D., Therrien V.A., Cummings C.L., Sergent P.A., Koulouris C.R., Friel A.M., et al. CD133 expression defines a tumor initiating cell population in primary human ovarian cancer. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2875–2883. doi: 10.1002/stem.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hermann P.C., Huber S.L., Herrler T., Aicher A., Ellwart J.W., Guba M., et al. Distinct populations of cancer stem cells determine tumor growth and metastatic activity in human pancreatic cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richardson G.D., Robson C.N., Lang S.H., Neal D.E., Maitland N.J., Collins A.T. CD133, a novel marker for human prostatic epithelial stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:3539–3545. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakai E., Park K., Yawata T., Chihara T., Kumazawa A., Nakabayashi H., et al. Enhanced MDR1 expression and chemoresistance of cancer stem cells derived from glioblastoma. Cancer Invest. 2009;27:901–908. doi: 10.3109/07357900801946679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shigeta J., Katayama K., Mitsuhashi J., Noguchi K., Sugimoto Y. BCRP/ABCG2 confers anticancer drug resistance without covalent dimerization. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:1813–1821. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chute J.P., Muramoto G.G., Whitesides J., Colvin M., Safi R., Chao N.J., et al. Inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase and retinoid signaling induces the expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11707–11712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603806103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong S.P., Wen J., Bang S., Park S., Song S.Y. CD44-positive cells are responsible for gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2323–2331. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prochazka L., Tesarik R., Turanek J. Regulation of alternative splicing of CD44 in cancer. Cell Signal. 2014;26:2234–2239. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wickstrom M., Larsson R., Nygren P., Gullbo J. Aminopeptidase N (CD13) as a target for cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:501–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saiki I., Fujii H., Yoneda J., Abe F., Nakajima M., Tsuruo T., et al. Role of aminopeptidase N (CD13) in tumor-cell invasion and extracellular matrix degradation. Int J Cancer. 1993;54:137–143. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910540122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujii H., Nakajima M., Saiki I., Yoneda J., Azuma I., Tsuruo T. Human melanoma invasion and metastasis enhancement by high expression of aminopeptidase N/CD13. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1995;13:337–344. doi: 10.1007/BF00121910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urabe A., Mutoh Y., Mizoguchi H., Takaku F., Ogawa N. Ubenimex in the treatment of acute nonlymphocytic leukemia in adults. Ann Hematol. 1993;67:63–66. doi: 10.1007/BF01788128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ota K., Uzuka Y. Clinical trials of bestatin for leukemia and solid tumors. Biotherapy. 1992;4:205–214. doi: 10.1007/BF02174207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shim J.S., Kim J.H., Cho H.Y., Yum Y.N., Kim S.H., Park H.J., et al. Irreversible inhibition of CD13/aminopeptidase N by the antiangiogenic agent curcumin. Chem Biol. 2003;10:695–704. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu D., Chen Z. The effect of curcumin on breast cancer cells. J Breast Cancer. 2013;16:133–137. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2013.16.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryan J.L., Heckler C.E., Ling M., Katz A., Williams J.P., Pentland A.P., et al. Curcumin for radiation dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of thirty breast cancer patients. Radiat Res. 2013;180:34–43. doi: 10.1667/RR3255.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin T.H., Lee S.O., Niu Y., Xu D., Liang L., Li L., et al. Differential androgen deprivation therapies with anti-androgens casodex/bicalutamide or MDV3100/enzalutamide versus anti-androgen receptor ASC-J9(R) lead to promotion versus suppression of prostate cancer metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:19359–19369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.477216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanai M., Otsuka Y., Otsuka K., Sato M., Nishimura T., Mori Y., et al. A phase I study investigating the safety and pharmacokinetics of highly bioavailable curcumin (theracurmin) in cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:1521–1530. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2151-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scott A.M., Allison J.P., Wolchok J.D. Monoclonal antibodies in cancer therapy. Cancer Immun. 2012;12:14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stern M., Herrmann R. Overview of monoclonal antibodies in cancer therapy: present and promise. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;54:11–29. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borthakur G., Rosenblum M.G., Talpaz M., Daver N., Ravandi F., Faderl S., et al. Phase 1 study of an anti-CD33 immunotoxin, humanized monoclonal antibody M195 conjugated to recombinant gelonin (HUM-195/rGEL), in patients with advanced myeloid malignancies. Haematologica. 2013;98:217–221. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.071092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lambert J.M. Drug-conjugated antibodies for the treatment of cancer. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76:248–262. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kasman L.M. CD13/aminopeptidase N and murine cytomegalovirus infection. Virology. 2005;334:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]