Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitates aggressive infection mitigation strategies to reduce the risk to patients and healthcare providers. This document is intended to provide a framework for the adult cardiac surgeon to consider in this rapidly changing environment. Preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative detailed protective measures are outlined. These are guidance recommendations during a pandemic surge to be used for all patients while local COVID-19 disease burden remains elevated.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: AGP, aerosol-generating procedure; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; COVID-19, novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (coronavirus disease 2019); Ig, immunoglobulin; OR, operating room; PPE, personal protective equipment; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography

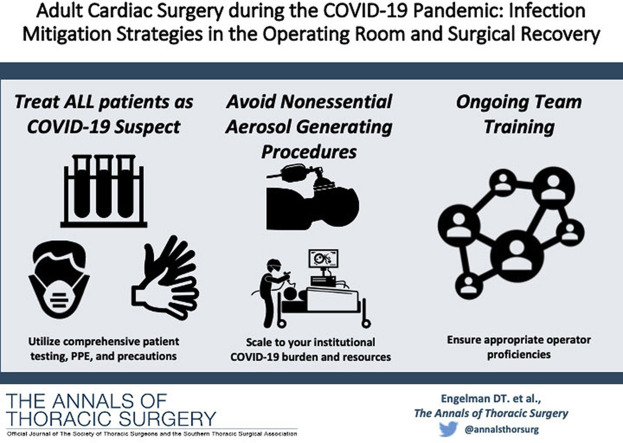

Visual Abstract

Dr Engelman discloses a financial relationship with Edwards Lifesciences; Dr Arora with Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, Abbott Nutrition, and Edwards Lifesciences.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently published recommendations for the care of patients undergoing surgical procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic.1 , 2 Additional modifications provided by the American College of Surgeons offer further guidance for surgical patients and personnel.3 Both organizations have recommended significantly reducing or stopping elective cases and implementing logical, tiered general precautions. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons COVID-19 Task Force and the Workforce for Adult Cardiac and Vascular Surgery published tiered patient triage guidance.4 Other suggestions from the American College of Surgeons to enhance safety for healthcare workers3 in the context of COVID-19 include the following:

-

1.

Consider nonoperative management whenever it is clinically appropriate for the patient.

-

2.

Complete testing as close to the planned operative date (preferably <48 hours) to lessen the risk that a patient becomes positive while waiting for a surgical procedure.

-

3.

Avoid emergency surgical procedures during off hours, when possible, due to limited team staffing and the potential lack of optimal specialty specific expertise.

-

4.Perform aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs)5 in confirmed or suspected COVID-19 patients while practicing enhanced droplet/contact precautions, including an N95 mask, eye protection, gown and gloves, or a powered air-purifying respirator. Examples of known and possible AGPs include:

-

a.Intubation, extubation, bag mask ventilation, noninvasive ventilation (continuous positive airway pressure and bilevel positive airway pressure), airway suctioning, nebulizer therapies, bronchoscopy, chest tube insertion, thoracotomies, and pleural procedures

-

b.Electrocautery of blood or any other body fluids6

-

c.Endoscopy

-

a.

-

5.

Defer nonurgent cardiovascular testing.

-

6.

Distinguishing COVID-19 from other respiratory infections will be challenging; therefore, interventions will need to be applied broadly and not limited to patients with confirmed COVID-19.1

While helpful, these guidelines do not provide the granular guidance needed to address important aspects of the surgical management of cardiac surgical patients. In particular, there will remain a certain volume of patients who will still require urgent and emergent operations during this pandemic.

At time of writing this document, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the novel coronavirus associated with COVID-19 disease, has been associated with at least a 6% mortality in the United States in those patients with a confirmed diagnosis.7 The virus is well equipped with several virologic, epidemiologic, and clinical features that have contributed to its ability to rapidly spread through a global population. Specifically, a substantial number of asymptomatic or presymptomatic infections, with or without mild symptoms, are key to its effective dissemination throughout populations, including to healthcare providers.8 At times of documented or assumed community spread of COVID-19, it is reasonable to suspect that all patients could be carriers of the virus. As such, all patients should be considered COVID-19 suspects, regardless of testing availability or results, and all patients should be treated equally with precautions similar to those used in COVID-19–confirmed cases.

This approach is similar to the concept of universal precautions. This level of safety may not be required if community transmission and the burden of cases is low in specific areas. However, to minimize infectious risk to healthcare providers of patients undergoing cardiac surgical procedures in the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative period, additional detailed protective strategies are suggested. These are guidance recommendations during a pandemic surge for all patients until the supply chain for personal protective equipment (PPE) is restored and local COVID-19 disease burden is substantially reduced.

Guidance Recommendations

-

1.

Patients should be transferred directly to the operating room (OR), without stopping in the preoperative or postanesthesia care unit areas, to minimize exposure to other patients, staff, and other environments.

-

2.

“COVID-19 precautions” signs should be posted on all doors to the OR suite to inform staff of potential risks and minimize exposure.

-

3.

The OR should remain positive pressure, but the surrounding rooms (ie, anteroom[s]) must maintain a strict negative pressure ventilation system at more than −2.5 Pa at 12 or more air changes per hour.9

-

4.

All OR staff are required to practice enhanced droplet and contact precautions in the OR at all times. This includes the use of N95 respirator, eye protection, gown, and gloves. Given the possibility of false-negative testing (10%-30%),10 the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends that all anesthesia professionals should use PPE appropriate for AGPs for all patients during all diagnostic, therapeutic, and surgical procedures when working near the airway.11 We would broaden this recommendation to include all OR personnel.

-

5.

If N95 masks are to be reused (though not optimal) the CDC recommends a 5-day period of drying12 or preferably decontaminated using ultraviolet germicidal irradiation, vaporous hydrogen peroxide, or moist heat by autoclaving.12 , 13

-

6.

If a powered air-purifying respirator is used as an alternative to an N95 respirator and eye protection, practitioners should be cautioned that these devices may reduce the clarity of surgical loupes and positioning of headlights.

-

7.

A donning-and-doffing–trained observer14 is highly recommended because most nosocomial spread of COVID-19 occurs during this critical period.15 Ongoing donning-and-doffing simulation training should be regularly performed for continual refinement of safety processes.

-

8.

Limit entry/exit to a single OR entrance. Keep all OR doors closed as much as possible, and limit staff entry/reentry to keep OR pressures and air exchanges regulated.

-

9.

Before AGPs are performed, OR personnel must ensure that no more than the minimal number of staff required to safely achieve the procedure are present in the room.

-

10.During induction and endotracheal intubation, it is recommended that the anesthesiologist:

-

a.Be the most experienced available operator with the highest probability of first-pass intubation.

-

b.Limit the number of staff in the OR to the minimum needed to safely intubate (1 anesthesiologist plus 1 or 2 assistants).

-

c.At the discretion of the anesthesiologist, video laryngoscopy may be chosen over direct visualization to decrease the risk of droplet transmission.

-

d.Preoxygenate with 100% inspired oxygen and avoid bag-mask ventilation unless absolutely necessary.

-

a.

-

11.

After AGPs, including intubation, additional OR personnel should wait 30 minutes before entering the room (this is dependent on the efficiency of the air exchange in each OR suite; see point 3 above).

-

12.

Intraoperative staffing for the surgical case should be minimized to the minimal number needed to safely and efficiently complete the procedure.

-

13.

Staff relief for breaks should be provided only as necessary to preserve PPE and decrease the number of staff exposed and reentries.

-

14.

Smoke evacuation of electrosurgical devices should be used to minimize staff exposure to surgical smoke.6

-

15.

Patients should preferably recover in a negative-pressure isolation room when resources permit (in the postanesthesia care unit or intensive care unit). If negative-pressure isolation rooms are unavailable, consider early recovery in the OR before transfer to a single patient room.

-

16.

After the patient has left the OR, the OR should be closed for an appropriate standoff period to achieve greater than 99.9% aerosol clearance. The amount of time that aerosols stay suspended in the air will depend on a number of factors, including the size of the room, the number of air changes per hour, how long the patient was in the room, whether the patient was coughing or sneezing, and whether an AGP was performed. General guidance on clearance rates under differing ventilation conditions is available from the CDC.16

-

17.

After the standoff period, the OR suite must be cleaned using routine procedures with United States Environmental Protection Agency-approved hospital disinfectant.

-

18.

Operations should be performed by the most experienced available surgeons and assistants to limit exposure time in the OR. Junior residents and other learners should not be exposed unless absolutely necessary.

-

19.

Strong consideration to surgical approach and technique must be considered to optimize patient outcomes while minimizing exposure risk to providers. Use of laparoscopic or video-assisted thoracoscopic procedures should be avoided when possible due to risk of aerosolization from CO2 insufflation systems with inadvertent lung injury.

-

20.

Limit all routine preoperative and postoperative laboratory testing, imaging, and procedures to minimize personnel exposure.

-

21.

COVID-19 repeat testing is only required in postoperative patients when symptoms or signs of COVID-19 develop. Rapid COVID-19 testing is preferred when available.

-

22.

In the event of cardiac arrest or other medical emergency, all patients must continue to be treated as suspected or confirmed COVID-19 cases. This requires strict adherence to enhanced contact and droplet precautions. No patient interaction should be permitted before full PPE is donned. This likely represents an uncomfortable paradigm shift for surgeons accustomed to “jumping into lifesaving patient interactions with little regard to infectious risk.”

-

23.

For a cardiac arrest in the intensive care unit, only 1 provider should provide cardiopulmonary resuscitation while medications are administered. Cessation of advanced cardiac life support is at the discretion of the provider, but prolonged resuscitative efforts should be avoided due to futility and risk.17

-

24.

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) in an intubated, anesthetized patient has never been demonstrated to generate aerosols. However, many societies have classified TEE as an AGP. Clinicians should weigh the necessity of placing a TEE in each cardiac surgical patient against the theoretical concern of generating aerosols. If performed, all staff should wear an N95 mask. The most experienced echocardiographer should perform the examination, including probe insertion and removal.18

COVID-19 Testing

There is accumulating evidence indicating that a substantial fraction of COVID-19–infected individuals are asymptomatic.19, 20, 21 A study of skilled nursing facility residents infected with COVID-19 demonstrated that half were asymptomatic or presymptomatic at the time of contact tracing evaluation and testing.22 In a population-based study in Iceland, 43% of the participants who tested positive reported having no symptoms.23 A study of 215 pregnant women admitted for delivery in New York City found 15% were COVID-19 positive, 88% of whom were asymptomatic.24

Virologic studies have demonstrated viral RNA and viable virus among persons with asymptomatic and presymptomatic infection.20 , 22 , 25 If a high-fidelity, rapid point-of-care testing system is available, providers could consider screening preoperative patients immediately before a surgical procedure if time permits within a 24-hour window, particularly in areas of high COVID-19 disease burden. Positive screening tests should lead to reconsideration of the risks and benefits of proceeding with the planned surgical procedure. These patients may be in the presymptomatic or early symptomatic phase of infection and are likely at heightened risk of adverse outcomes after an operative procedure. In a retrospective cohort study of 34 patients who were unintentionally scheduled for elective operations during the incubation period of COVID-19, the mortality rate was 20%.26

However, negative screening tests must be interpreted with caution, particularly in the setting of (1) low pretest probability, (2) typically low viral titers in the asymptomatic phase, and (3) the possibility of false-negative results. If clinical suspicion for COVID-19 remains due to exposure history, active symptoms, high prevalence of circulating community infections, or other clinical factors, repeat testing may be indicated during the postoperative course.

Serologic Immunity

After viral infections, an immunoglobulin (Ig) M immune response occurs, which then diminishes within a few weeks. The IgG and IgA immune response occurs simultaneously, producing more specific and longer-acting immunity.27 Testing patients’ serostatus could be an important tool to determine whether patients have mounted prior immunity from natural infection, reducing the likelihood of current COVID-19 colonization. The prospect of testing providers for serologic immunity to COVID-19 is also promising if the presence of antibodies confers immunity to future infection, because providers with acquired immunity could be selected to care for COVID-19 suspected or confirmed patients.

Unfortunately, serologic testing and capacity are currently limited and require further scientific evidence to support their use in screening healthcare workers. Important studies are underway to determine the pattern of antibody development after COVID-19 infection, whether antibodies confer immunity to future infections, whether specific antibody titers determine the level of protection, and the duration of conferred immunity.

Similar coronavirus outbreaks demonstrated that survivors developed robust immunity after natural infection. The 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak elicited an immunity that was protective for up to 3 years.28 Until more data emerge supporting the widespread adoption of antibody testing,29 strict infection prevention and control policies are required to enhance the safety of patients and providers.

Conclusion

At the present time, we urge all healthcare organizations providing cardiac surgical procedures in regional environments of widespread COVID-19 disease to consider adopting these aggressive mitigation strategies (1) to create a safe environment that protects our patients from acquiring or transmitting COVID-19 and (2) to protect members of our surgical and postoperative provider teams. We all look forward to the near future when elective surgical procedures can be resumed as the threat of this virus wanes and capacity permits. However, until that time, and in an effort to hasten its arrival, the aforementioned protocols should become standard of care.

Acknowledgments

Rakesh C. Arora has received an unrestricted educational grant from Pfizer Canada Inc.

Footnotes

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the American Association for Thoracic Surgery support this document.

This article has been copublished in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery and The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons requests that this article be cited as: Engelman DT, Lother S, George I, Funk DJ, Ailawadi G, Atluri P, Grant MC, Haft JW, Hassan A, Legare J-F, Whitman GJR, Arora RC, on behalf of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons COVID-19 Task Force. Adult Cardiac Surgery and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Aggressive Infection Mitigation Strategies Are Necessary in the Operating Room and Surgical Recovery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110:707-711.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients With Suspected or Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Healthcare Settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html Available at:

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Healthcare Facilities: Preparing for Community Transmission. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/healthcare-facilities/guidance-hcf.html Available at:

- 3.American College of Surgeons COVID-19: Elective Case Triage Guidelines for Surgical Care. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case March 24, 2020. Available at:

- 4.Haft J.W., Atluri P., Ailawadi G. , on behalf of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons COVID-19 Task Force and the Workforce for Adult Cardiac and Vascular Surgery. Adult cardiac surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: a tiered patient triage guidance statement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110:697–700. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tran K., Cimon K., Severn M., Pessoa-Silva C.L., Conly J. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y., Song Y., Hu X., Yan L., Zhu X. Awareness of surgical smoke hazards and enhancement of surgical smoke prevention among the gynecologists. J Cancer. 2019;10:2788–2799. doi: 10.7150/jca.31464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Coronavirus Research Center Maps & Trends. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data Available at:

- 8.Li R., Pei S., Chen B. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Science. 2020;368:489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Infection Control. Background C. Air: Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities (2003) https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/environmental/background/air.html Available at:

- 10.Yang Y., Yang M., Shen C. Evaluating the accuracy of different respiratory specimens in the laboratory diagnosis and monitoring the viral shedding of 2019-nCoV infections. MedRxiv. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.02.11.20021493v2 Available at:

- 11.American Society of Anesthesiologists Update: The Use of Personal Protective Equipment by Anesthesia Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://www.asahq.org/about-asa/newsroom/news-releases/2020/03/update-the-use-of-personal-protective-equipment-by-anesthesia-professionals-during-the-covid-19-pandemic March 22, 2020. Available at:

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Decontamination and Reuse of Filtering Facepiece Respirators. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/decontamination-reuse-respirators.html Available at:

- 13.Kumar A., Kasloff S.B., Leung A. N95 mask decontamination using standard hospital sterilization technologies. MedRxiv. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.05.20049346v1 Available at:

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Ebola: Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Donning and Doffing Procedures. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/ppe-training/trained-observer/observer_02.html Available at:

- 15.Suen L.K.P., Guo Y.P., Tong D.W.K. Self-contamination during doffing of personal protective equipment by healthcare workers to prevent Ebola transmission. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7:157. doi: 10.1186/s13756-018-0433-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infection Control Appendix B. Air: Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities (2003) https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/environmental/appendix/air.html#tableb1 Available at:

- 17.Shao F, Xu S, Ma X, et al. In-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes among patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Resuscitation. 2020;151:18-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.American Society of Echocardiography Specific Considerations for the Protection of Patients and Echocardiography Service Providers When Performing Perioperative or Periprocedural Transesophageal Echocardiography During the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak: Council on Perioperative Echocardiography Supplement to the Statement of the American Society of Echocardiography. https://www.asecho.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/COPE_COVID_Supplement_FINAL.pdf Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.National Public Radio CDC Director on Models for the Months to Come: 'This Virus Is Going To Be With Us.’ March 31, 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/03/31/824155179/cdc-director-on-models-for-the-months-to-come-this-virus-is-going-to-be-with-us? Available at:

- 20.Hoehl S., Rabenau H., Berger A. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in returning travelers from Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1278–1280. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.John T. Iceland lab's testing suggests 50% of coronavirus cases have no symptoms. April 3, 2020. Cable News Network. https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/01/europe/iceland-testing-coronavirus-intl/index.html Available at:

- 22.Kimball A., Hatfield K.M., Arons M. Asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in residents of a long-term care skilled nursing facility--King County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:377–381. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gudbjartsson D.F., Helgason A., Jonsson H. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the Icelandic Population. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2302–2315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2006100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sutton D., Fuchs K., D’Alton M., Goffman D. Universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 in women admitted for delivery. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2163–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang W.H., Guan W.J., Li C.C. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 treated in Hubei (epicenter) and outside Hubei (non-epicenter): a nationwide analysis of China. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2000562. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00562-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sethuraman N., Jeremiah S.S., Ryo A. Interpreting diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;323:2249–2251. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu L.P., Wang N.C., Chang Y.H. Duration of antibody responses after severe acute respiratory syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1562–1564. doi: 10.3201/eid1310.070576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Branswell H. CDC launches studies to get more precise count of undetected Covid-19 cases. April 4, 2020. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2020/04/04/cdc-launches-studies-to-get-more-precise-count-of-undetected-covid-19-cases/ Available at: