Abstract

Objective:

Assess differences in approaches to and provision of developmental care for infants undergoing surgery for congenital heart disease.

Study design:

A collaborative learning approach was used to stratify, assess, and compare individualized developmental care practices amongst multidisciplinary teams at six pediatric heart centers. Round robin site visits were completed with structured site visit goals and post-visit reporting. Practices of the hosting site were assessed by the visiting team and reviewed along with center self-assessments across specific domains including pain management, environment, cue-based care, and family based care coordination.

Results:

Developmental care for infants in the cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) varies at both a center and individual level. Differences in care are primarily driven by variations in infrastructure and resources, composition of multidisciplinary teams, education of team members, and use of developmental care champions. Management of pain follows a protocol in most CICUs, but the environment varies across centers, and the provision of cue-based infant care and family based care coordination varies widely both within and across centers. The project led to proposed changes in clinical care and center infrastructure at each participating site.

Conclusions:

A collaborative learning design fostered rapid dissemination, comparison, and sharing of strategies to approach a complex multidisciplinary care paradigm. Our assessment of experiences revealed marked variability across and within centers. The collaborative findings were a first step towards strategies to quantify and measure developmental care practices in the CICU to assess the association of complex inpatient practices with long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Keywords: Congenital Heart Disease, Collaborative Learning Design, Cardiac Intensive Care Unit, Individualized Developmental Care, NIDCAP

Neurodevelopmental disabilities are a highly prevalent and perplexing comorbidity of congenital heart disease (CHD). Few modifiable risk factors have been identified and these explain less than one third of the observed variation in ND outcomes.1, 2 Hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) lengths of stay (LOS) consistently predict poor ND outcomes, highlighting the potential impact of the stressful perioperative environment on brain development during this critical window.3–5 Individualized developmental care is an approach to care for hospitalized infants that includes reading the infant’s cues, parental engagement, and the provision of a supportive environment.6 Developmental care practices that mitigate the infant stress experience are promising as modifiable factors that may change the trajectory of ND outcomes in CHD.

Developmental and family-integrated care strategies have been combined to form comprehensive programs, such as the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP).7 NIDCAP is an evidence based, comprehensive, internationally recognized program of individualized developmental care which has been shown to improve outcomes for premature infants including enhanced brain structure and function, along with improved behavioral and medical outcomes.8–10 Given the similarities in brain dysmaturity and patterns of neurologic injury between premature infants and those with CHD,11–13 it is compelling to speculate that improved developmental care for high risk infants with CHD may improve ND outcomes as well.

Collaborative learning is a unique method for studying complex care practices, such as developmental care, overcoming site specific barriers to implementation, and developing strategies to test the impact of individual approaches.14, 15 Collaborative learning allows teams to share knowledge, skills, resources, and experience to enhance performance of a specific process. It promotes rapid evaluation and dissemination of beneficial practices that require the input of multiple disciplines.16 For complex care processes, collaborative learning is superior to other methodologies, such as surveys of practices, where information is obtained on what the respondents say they do rather than observations and discussions of what is done in practice.17 This study aimed to compare and contrast developmental care practices for newborns in the CICU in the absence of well-defined best practices in cardiology. This report presents the findings associated with the iterative, collaborative process.

METHODS

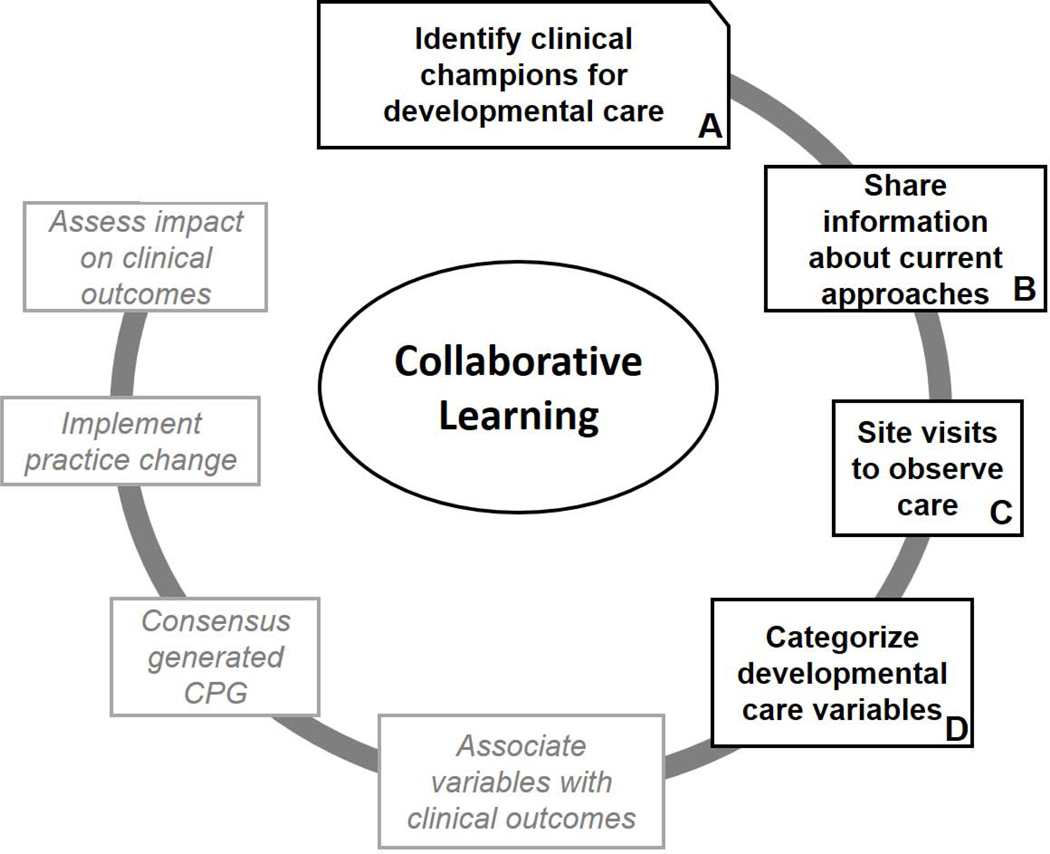

The rationale for a collaborative learning approach to clinical practices in CHD lacking best practice guidelines has been previously described.16 The design was adapted from lessons learned in previous studies. Figure 1 demonstrates the steps of the collaborative learning method used in this project. Each step was approached in a collaborative, iterative process. The study team was established across six sites within the Pediatric Heart Network (PHN) (Figure 1, A). Group correspondence allowed all participants the opportunity to critique the proposed approach and methods. Although the collaborative process was iterative, the approach was different from a quality improvement (QI) project. Notably, there were no SMART (Specific, Measureable, Applicable, Realistic and Timely) aims, measures, or balance measures. Preparation for site visits included monthly conference calls. The first group objective was to categorize sites’ current developmental care practices (Figure 1, B). For the categorization, each site was required to list all practices, guidelines, protocols, and services that they felt contributed to the individualized developmental care of infants with CHD in the CICU. Through iterative organization, discussion, and reorganization, practices were stratified into main categories and sub-categories. Based on the established stratification, each visiting team was required to create a document of “Site Visit Goals” which they shared with the hosting site as a visiting itinerary was prepared. The members of the visiting team were determined by the visiting site principle investigator.

Figure 1: Schematic of the Collaborative Learning approach.

The diagram (adapted from previous experience with Collaborative Learning in the Pediatric Heart Network16) outlines the stepwise approach proposed to systematically assess the impact of developmental care on clinical outcomes in Congenital Heart Disease. In the absence of an established standard, the process begins with evaluating and distilling current approaches and differences between sites. This manuscript describes the findings of the steps in bold.

Collaborating centers were relatively large (Table I) and all had dedicated CICUs. Site visits occurred between December 2018 and March 2019, with each center visiting a different site than they hosted. Visits were 1–2 days long and included observation of clinical care performed by nurses and therapists, along with scheduled interviews with nurses, administrators, physicians, and therapists. Direct observations included nursing care, therapist care, and multidisciplinary rounds (Figure 1, C). Individuals involved in the collaborative learning site visits represented multiple disciplines (Table 1). Collaborative learning site visits focused on observing the key elements of individualized developmental care, based on the previously determined site visit goals, including identify clinical champions for developmental care and its sustainability, assess current developmental care practices, routines, and protocols, evaluate strengths, weakness, successes, and barriers to developmental care infrastructure. Observations and impressions were collected in a structured format based on the determined categories and sub-categories of developmental care variables. Qualitative analytic methods were not used, but information from site visits was reviewed on monthly conference calls between the entire research team. Each visiting team was required to write a summary report that highlighted observations of strengths, weakness, differences between the hosting site and their own center, and differences they observed from patient to patient that could be categorized into developmental care variables (Figure 1, D). Each team was also required to report what aspects of the site visits were beneficial. Sites were required to propose potential strategies to improve local care based on observed differences during their site visit. Common themes were identified and articulated on the calls and compiled into descriptive format by the principle investigator.

Table 1: Sites.

Participating site size based on number of beds in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit (CICU) and surgical volume (total cases). Subspecialty and discipline of the site principle investigator (PI) and visiting team members are listed.

| Collaborating Center | Number of CICU beds | Estimated surgical volume (cases/year) | Estimated newborn surgical volume (cases/year) | Site PI subspecialty | Visiting team disciplines |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH) | 31 | 1400 | 300 | Cardiac Neurodevelopment | Psychologist, Bedside nurse, Nurse practice specialist |

| Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta | 27 | 850 | 175 | Cardiology | Physician, Physical therapist, psychologist |

| Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia | 28 | 900 | 200 | Nursing Science | Nurse scientist, Psychologist, Occupational therapist |

| Texas Children’s Hospital |

48 | 950 | 200 | Critical Care | Physical therapist, Physician |

| University of Michigan | 22 | 750 | 160 | Cardiology/Cardiac Surgery |

Physical therapist, Nurse practitioner, Physician, Nurse scientist |

| University of Utah | 16 | 500 | 145 | Cardiology | Physical therapist, Speech and language pathologist, Physician |

Every site completed a subset of the NIDCAP Nursery Assessment Manual (NNAM)7, 18 selected based on relevance to the collaborative learning site visits. NIDCAP is a well-established, evidence-based program to provide individualized developmental care in hospitals and is used worldwide.7 The therapeutic method of individualized developmental care in the NIDCAP model provides early support and preventive intervention based on each child’s behavioral signals of stress, comfort and strength. The individualized adaptation and planning of care is based on careful, detailed, repeated observation of behavioral cues and communication and requires training that leads to certification. NIDCAP has been shown to improve outcomes for premature infants, with enhanced brain structure and function, improved behavioral outcomes that endure beyond infancy and into school age, along with benefits in medical variables and parental engagement.8–10, 19–25 The NNAM is a measure of an ICU’s commitment to and integration of the principles of NIDCAP for infants, families and staff. The NNAM consists of 121 scales grouped into four domains of functioning (physical environment, as well as philosophy and implementation of infant care, of family care, and of staff care).18 Each scale is rated on a 5 point continuum from 1= traditional care to 5=highly attuned individualized developmental care. NIDCAP training and consultation intends to aid the ICU in achieving ultimately consistent developmental care implementation with scores of 3.5 or better. Subsections of the NNAM were completed at each center by a group of at least 3 self-identified multidisciplinary clinical champions of developmental care, which included therapists, bedside nurses, physicians and nursing leadership. Individual sites did not receive NIDCAP training prior to scoring of the NNAM, however the senior author (SB) is a certified NIDCAP professional and provided guidance on NIDCAP and the scoring of the NNAM prior to implementation.

Participating sites compiled all of their procedures and practices that each local team felt to be relevant to the provision of developmental care. The iterative approach to listing and organizing local care practices was initially undertaken with a goal of creating measureable variables likely associated with clinical outcomes. Through ongoing discussion, the team acknowledged that many practices were fluid, intimately integrated, and rarely documented. Furthermore, despite the initial objective of describing variables associated with outcomes, the team recognized that many important aspects of individualized developmental care currently supported would be difficult to measure objectively while nevertheless important to observe. Care was ultimately categorized into four groups, similar to the NIDCAP Nursery approach 7,18: Personalized and Cue-based Care and Therapies, Family Based Care and Coordination, Environment, and Staff. Each category was further subdivided to organize and include all of the procedures and practices. The category of personalized and cue-based cares and therapies included the sub-categories: therapy assessment and intervention, infant caregiving, approaches to comfort, positioning, sleep, developmental rounds/multidisciplinary planning, and formal test/assessments. The category of family based care coordination included the sub-categories: developmental rounds/multidisciplinary planning, daily scheduling, care plans, needs assessment and support, family involvement in cares. The category of environment included the subcategories: light and sound, temperature, stimulation. The category of staff included the subcategories: standing referrals and provider education.

RESULTS

Overall summary reports were prepared by the visiting teams. Frequently noted areas of difference based on the strengths and weakness are listed in Table 2. Below are some highlights and example observations in each of the four categories. The highlights represent a limited selection of the summary work representative of common themes.

Table 2: Areas of Differences and Potential Changes to Improve Care.

Most frequently noted differences in delivery of developmental care during site visits and the proposed changes to local care that teams made when returning to their own site are listed in the table.

| Common Areas of Difference | |

| Site Differences | Patient-to-Patient Variability |

| Integration of therapy and medical teams | Skin to skin care |

| Bedside nurse understanding of developmental care and non-pharmacologic approaches to comfort | Bedside nurse understanding of developmental care and non-pharmacologic approaches to comfort |

| PT/OT/Speech: timing of treatment initiation | TV |

| PT/OT/Speech: duration/frequency of therapy | Parental presence and participation in caregiving |

| Frequency and use of chaplaincy, music therapy, social work, and child life | Light level |

| Understanding and use of therapeutic positioning | Temperature |

| Sternal precautions | Sound level |

| Integration of infant behavioral assessment/reading infant cues into caregiving | 4 handed care and other non-pharmacologic approaches to comfort |

| Holding: duration, frequency; with consideration of whether it was appropriate for state | Bedding, use of blankets and other supports to provide boundaries around the infant for comfort and therapeutic positioning |

| Physical restraints to limb movement | Clothing, sleep sacks, buntings. |

| General alignment with NIDCAP philosophy/practice | |

| Developmental care rounds, plans, and education | |

| Support for families | |

| Changes in Practice | |

| Infrastructure | Practices |

| Formal delineation of team leads for neurodevelopmental care | Display ‘developmental milestones’ to increase recognition of infants that need extra support |

| Appoint nurse leader for education on incorporating infant behavioral assessment into nursing care | Start “quiet time” in the CICU |

| Acquired light and sound monitors to quantify variations in environment | Increase utilization of music therapy |

| Improve relationship and communication between therapy and medical teams | Evaluate receipt of developmental plans at discharge |

| Start a cardiac specific outpatient feeding program | Consider maternal depression screening for families and increase supports available |

| Integration of meeting between inpatient and outpatient developmental care teams | Initiation of Developmental Care Rounds |

| Creation of multi-disciplinary developmental care education committee and inpatient developmental care workshop for Heart Center members | Provide staff education to improve communication with families and increase parent engagement and support at the bedside. |

| Consider formalized NIDCAP training for staff | |

In the category of Personalized and Cue-based Care, observers most often described the approaches of the therapy team members. For example: “We observed the therapist consult with the bedside RN re: patient’s status and availability for intervention. RN shared that the infant had undergone a procedure during the day and had received medications that made the infant’s state less than ideal for intervention. … We observed the therapist proceeding slowly & gently, providing manual containment cephalocaudally and posteriorly at various times, promoting self-soothing with assisted hand-to-mouth with state changes during intervention, and monitoring vital signs. ” Many observers noted similarities between the therapy teams across sites and their approaches to infant cues and educating other caregivers of the same. Many sites noted the use of two caregivers, including family members, working together so that one concentrated on supporting the infant’s state and reading the infant’s cues while the other preformed the necessary medical intervention. There were more notable differences, both across and within sites, regarding nursing understanding and incorporation of reading infant cues into their ‘routine’ care and following an infant driven as opposed to a nursing caregiving driven schedule.

In the category of Family Based Care and Coordination, there was apparent consistency in the inclusion of families for discussion of care: “Family inclusion at bedside rounds was similar between the two sites with extensive engagement and active listening to parental concerns as long as they were present at the time of rounding. ” But there was considerable variability in family involvement with care, both systematically and individually: “We did not observe many families at the bedside. A few mothers were holding their infants but otherwise we were unable to see how parents are engaged in care. The nurses described ‘allowing ‘ parents to hold infants who were intubated, but not with intracardiac lines . … Skin to skin care was not routinely offered as an option for parents in the pre- or postoperative period. ” As opposed to: “ The program has made efforts to ‘allow’ parents to hold and have skin to skin contact with their babies while in the intensive care unit. This would include patients who have indwelling right atrial lines and patients who are mechanically ventilated. There did seem to be variability in the use of this strategy.” And, “Skin to skin holding is encouraged and supported by the multidisciplinary team. ” The coordination of developmental care priorities and updates to both the family and other team members regarding those priorities appeared to be dependent on the structure of developmental rounds. Some sites did not have any developmental rounding, and some performed bedside rounds, and others had multidisciplinary rounds in a conference room prior to reporting back to the bedside. Documentation of the findings on developmental rounds also varied, with some completing notes in the electronic medical record and others focusing on updating bedside notifications for parents and care providers on individual priorities. Family mental health was noted in the structured interviews to be a high priority at most sites, but successful implementation of screening for maternal and/or paternal anxiety and depression occurred at only a few sites.

In the category of Environment, observers noted similarities in attempts to decrease noxious stimuli with multiple unit-based efforts to specifically decrease ambient sound and light. Use of day/night light cycles and “quiet time/nap time” was common, although variations in the sound levels were observed. Television use also varied, despite site specific guidelines, with one observation of the “… TVs in CICU on adjustable arms allowing the screen to be right in front of the child’s face which we observed in one room, while the child was sleeping, ” but another “There are televisions in each patient room, but during our visit none appeared to be in use. ” Some noted the variations in the number of private rooms in the CICU having a bigger impact on sound than the unit-based quiet times. Soothing sounds, white noise machines, parent voice recordings, and encouragement for parents to talk or read to their infants were commonly observed. Approaches to limiting excessive light stimulation varied across centers with some minimizing the ambient lighting near the bed spaces and others using eye shields/tents to reduce direct lighting on the infant’s eyes.

In the category of Staff, the group noted key differences amongst sites in the clinical champions and composition of the inpatient neurodevelopmental teams. The primary lead for inpatient ND and individualized developmental care at different sites was a nurse scientist, a physician, a therapist, or a psychologist. The make-up of the multidisciplinary teams also varied widely. The ability of a specific discipline to contribute to developmental rounds and ongoing educational activity appeared dependent on the support of leadership and infrastructure, which differed from site to site. For example, one visit summary included the following statement: “The second major thematic difference was the nursing infrastructure for ongoing education . … there are four advanced practice nurses in the Clinical Nurse Specialist role with at least one circulating in the CICU every day to help new graduates with care as well as reinforce new initiatives (such as developmental care). … If the nursing experience does not match the complexity of the case, there is an increase in support from resource nurses, clinical nurse specialists, and other nearby nurses. … They admitted that they had to have a change in culture a while back from one of ‘asking for help being a sign of weakness ‘ to one where asking for help was routine. This has spilled over into developmental care practice, for example, with hand containment (cranial-caudal hold) routinely provided by a neighboring nurse when someone completes a routine care.” And from another summary: , “it was obvious throughout the visit that the support for rehab professionals ‘ roles in developmental care is appreciated, welcomed and championed at the highest levels of the cardiac team, and that the rehab therapists are proactive in modeling, training and promoting developmental care. The therapists shared that “Rehab Services ” is a line item in the daily review of systems in medical provider notes. ” The group found similar approaches to financial support. Specifically, funding for dedicated time for clinical champions to organize developmental care infrastructure was dependent on support of heart center leadership. Therapy, social work, and psychology services provided to the patient and family, however, were often reimbursable and billed similarly across centers.

The self-assessments regarding a center’s likelihood to deliver developmentally appropriate individualized care based on a selection of NNAM18 scales are shown in Figure 2. Although the centers appeared to have a similar pattern to their ranking of how they assessed and managed pain (Figure 2, C), patterns to self-scores on environment were divergent between sites (Figure 2 A) and on caregiving divergent between and within sites (Figure 2, D). Despite the possibility of inflated scores, due to lack of formal NIDCAP training, all of the sites’ scores routinely fell below the NIDCAP best practice standards and many areas of opportunity for change and improvement were noted.

Figure 2: Care Self-Assessment:

Distribution of self-assessment scores in selected domains of the Physical Environment of the Hospital and Nursery and Philosophy and Implementation of Care: Infant subdomains from the NIDCAP Nursery Assessment Manual.18 Each scale is rated on a 5 point continuum from 1= traditional care to 5=highly attuned individualized developmental care. NIDCAP training and consultation intends to aid the ICU in achieving ultimately consistent developmental care implementation with scores of 3.5 or better.

Following site visits, teams were asked to revisit their self-assessments and consider their own strengths and weakness based on their observations and discussions on the monthly conference calls. Each center created a list of potential strategies to improve local care based on observed differences and particular successes of other programs they wanted to emulate. The identified strategies included infrastructure changes as well as modifications to care practices and are listed in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

Teams found that the collaborative and shared learning design was well suited to examine practice variation. The tenets of collaborative learning are based in cognitive development theory, suggesting that there are certain tasks that learners cannot complete without the aid of another.26 Although typically applied to childhood development, these concepts regarding leveraging the skills of another for advancement of knowledge in both parties is well suited to clinical care paradigms that lack best practice standards. This approach promoted rapid evaluation and dissemination of practices which has been previously challenging for developmental care in the CICU. The multidisciplinary team-based approach to this project, allowed for simultaneous input from multiple perspectives while evaluating specific aspects of the care model. In addition, multiple disciplines participating in the same observations and evaluations fostered rapid turnaround to proposed local initiatives.

The requirement of multiple disciplines to integrate appropriately in order to deliver individualized developmental care is likely one of the key drivers of the variation observed. We found that some of the biggest differences were in the make-up and support of the clinical champions at each site and their ability to implement change was dependent on varied levels of administrative and infrastructure support. For example, the site difference in Table 2 regarding nursing understanding of developmental care was dependent on nursing education infrastructure, independent of individual nursing interest. Similarly, the site difference in Table 2 regarding PT/OT/Speech timing and duration of therapy was dependent on staffing and support from a department that may or may not report to the cardiac service line. Our findings support previously published concerns that developmental care practices fluctuate within and across CICUs.27, 28 The core components of individualized family-centered developmental care have been previously described and include parent engagement, cue-based care, and supportive environment.6 Although our process of compiling and organizing all policies and procedures led to three of our categories matching these core components, we also had a fourth category of staff, which highlights how infrastructure and support for those providing care can lead to variability in outcomes. We found many similarities in how the individual clinical champions at each site, even if from different training backgrounds, approached individualized developmental care. A lot of successes described by the observers had a similar theme of the heart center empowering those champions. Ideally the next step would be to provide formal individualized developmental care training and then study the impact of improving developmental care on longer term outcomes.

Individualized developmental care improves neurodevelopment and psychosocial outcomes for preterm infants and their families and it is felt to be best practice for vulnerable high-risk infants. 19, 10,19–25, 29–32 The intervention of developmental care is designed to minimize the mismatch between the fragile brain’s expectations and the experiences of stress and pain inherent in an ICU environment. According to the NIDCAP approach, an ICU that provides individualized, developmentally-supportive, and family-centered care includes a soothing environment, which encourages sleep and healing, supports parents as their child’s primary caregiver, and provides continual adjustment of caregiving in support of the child’s wellbeing, strengths, and healing.7 The developmental and family-integrated care strategies in comprehensive NIDCAP programs report benefits for clinical outcomes such as decreased length of ICU and of hospital stay, earlier oral feeding, and increased weight gain.8, 19–24, 33 NIDCAP increases parental engagement at the bedside, attachment to their infant, and confidence in caregiving.25, 34–36

Comparing NIDCAP self-assessments across sites, a relative confidence in the ability to monitor and treat pain appropriately was found, likely driven by robust experience in post-operative pain management. Non-pharmacologic approaches to pain, however, were acknowledged as a relative weakness across most of the sites, possibly driven by the often more acute recovery timeframe seen in the CICU compared with the newborn ICU. Self-assessment scoring trends were more widely variable in the domains of care plans, environment and most notably caregiving. Variability was due to inconsistency in practice within hospitals, across caregivers and shifts with limited knowledge in regards developmental care. Variations in perceptions of appropriate care are a limitation to the subjective self-assessments. Discussion among the site members and a NIDCAP Professional along with concurrent involvement in collaborative site visits, however, likely improved objectivity in the self-assessments.

Additional limitations to this project are similar to those of consensus-based guidelines. Specifically, the collaborative approach is grounded in opinion and although the six sites provide care for a diverse range of ethnic groups, disease entities, geographical distribution, parental education, and socioeconomic status, generalizability to heart centers of different size, with different resources, and different infrastructure may be limited. All six participating centers have invested in developmental care by supporting the clinical champions with time to spend on poorly reimbursable activities. Furthermore, it is unclear if the findings from six dedicated CICUs are representative of developmental care provided in newborn or pediatric ICUs. Regardless, the lack of standardization in practice in individualized developmental care amongst the six sites supported the need for this descriptive project prior to proposing more quantitative approaches.

Providing individualized developmental care in the CICU requires a unique infrastructure that depends on resources and clinical champions that may differ at each center. Although many CICUs are enthusiastic to optimize developmental care, the success and sustainability of implementation as well as its impact on outcomes requires further investigation.

Acknowledgements:

We acknowledge the important contributions of the following individuals to the site visits: Abigail Demianczyk, PhD; Jeanne Cribben, MSOT, OTR/L; Robin Schlosser, DPT; Christine Rachwal, MSN, RN, CCRN, CWOCN; Meena LaRonde, MSN, RN, CCRN; Courtney Jones, SLP; Lauren Malik, PT; Kristi Glotzbach MD; Kimberly Kellogg, BSN, MS, CPNP; Christopher Tapley, MS, PT; Annalia Polemitis, PT. We also thank Heidelise Als, PhD for support in use of the NIDCAP Nursery Assessment Manual and article review. Dr Als is the author of the NIDCAP certification scales but has no conflicts of interest with this project and there was no financial remuneration for her support of the use of NIDCAP scales in the project

Funded by the NHLBI and Pediatric Heart Network.

Abbreviations:

- CHD

Congenital Heart Disease

- CICU

Cardiac Intensive Care Unit

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

- LOS

Length of Stay

- NIDCAP

Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program

- NNAM

NIDCAP Nursery Assessment Manual

- QI

Quality Improvement

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Gaynor JW, Wernovsky G, Jarvik GP, Bernbaum J, Gerdes M, Zackai E, et al. Patient characteristics are important determinants of neurodevelopmental outcome at one year of age after neonatal and infant cardiac surgery. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2007;133:1344–53, 53 e1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Goldberg CS, Lu M, Sleeper LA, Mahle WT, Gaynor JW, Williams IA, et al. Factors associated with neurodevelopment for children with single ventricle lesions. The Journal of pediatrics. 2014;165:490-6.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Newburger JW, Wypij D, Bellinger DC, du Plessis AJ, Kuban KC, Rappaport LA, et al. Length of stay after infant heart surgery is related to cognitive outcome at age 8 years. The Journal of pediatrics. 2003;143:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Andropoulos DB, Ahmad HB, Haq T, Brady K, Stayer SA, Meador MR, et al. The association between brain injury, perioperative anesthetic exposure, and 12-month neurodevelopmental outcomes after neonatal cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Paediatric anaesthesia. 2014;24:266–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Butler SC, Sadhwani A, Stopp C, Singer J, Wypij D, Dunbar-Masterson C, et al. Neurodevelopmental assessment of infants with congenital heart disease in the early postoperative period. Congenital heart disease. 2019;14:236–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lisanti AJ, Vittner D, Medoff-Cooper B, Fogel J, Wernovsky G, Butler S. Individualized Family-Centered Developmental Care: An Essential Model to Address the Unique Needs of Infants With Congenital Heart Disease. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;34:85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Als H. Program Guide - Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP): An Education and Training Program for Health Care Professionals. Boston: Copyright, NIDCAP Federation International 1986 rev 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Als H, Duffy F, McAnulty GB, Rivkin MJ, Vajapeyam S, Mulkern RV, et al. Early experience alters brain function and structure. Pediatrics. 2004;113:846–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].McAnulty GB, Duffy FH, Butler SC, Bernstein JH, Zurakowski D, Als H. Effects of the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) at age 8 years: preliminary data. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2010;49:258–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Silberstein D, Litmanovitz I. [Developmental Care in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit According to Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (Nidcap)]. Harefuah. 2016;155:27–31, 68, 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Morton PD, Ishibashi N, Jonas RA, Gallo V. Congenital cardiac anomalies and white matter injury. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38:353–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Morton PD, Ishibashi N, Jonas RA. Neurodevelopmental Abnormalities and Congenital Heart Disease: Insights Into Altered Brain Maturation. Circulation research. 2017;120:960– 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].McQuillen PS, Goff DA, Licht DJ. Effects of congenital heart disease on brain development. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;29:79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Weaver SJ, Lofthus J, Sawyer M, Greer L, Opett K, Reynolds C, et al. A Collaborative Learning Network Approach to Improvement: The CUSP Learning Network. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2015;41:147–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Leroy L, Rittner JL, Johnson KE, Gerteis J, Miller T. Facilitative Components of Collaborative Learning: A Review of Nine Health Research Networks. Healthc Policy. 2017;12:19–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wolf MJ, Lee EK, Nicolson SC, Pearson GD, Witte MK, Huckaby J, et al. Rationale and methodology of a collaborative learning project in congenital cardiac care. American heart journal. 2016;174:129–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kelley K, Clark B, Brown V, Sitzia J. Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15:261–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Smith K BD, Als H. NIDCAP Nursery Certification Criterion Scales. Copyright NIDCAP Federation International; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Als H, Lawhon g, Duffy FH, McAnulty GB, Gibes-Grossman R, Blickman JG. Individualized developmental care for the very low birthweight preterm infant: Medical and neurofunctional effects. JAMA. 1994;272:853–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Als H, Gilkerson L, Duffy FH, McAnulty GB, Buehler DM, VandenBerg KA, et al. A three-center randomized controlled trial of individualized developmental care for very low birth weight preterm infants: Medical, neurodevelopmental, parenting and caregiving effects. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2003;24:399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Buehler DM, Als H, Duffy FH, McAnulty GB, Liederman J. Effectiveness of individualized developmental care for low-risk preterm infants: Behavioral and electrophysiological evidence. Pediatrics. 1995;96:923–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Westrup B, Böhm B, Lagercrantz H, Stjernqvist K. Preschool outcome in children born very prematurely and cared for according to the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP). Acta Paediatrica. 2004;93:498–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Westrup B, Kleberg A, von Eichwald K, Stjernqvist K, Lagercrantz H. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effects of the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program in a Swedish setting. Pediatrics. 2000;105:66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kleberg A, Westrup B, Stjernqvist K, Lagercrantz H. Indications of improved cognitive development at one year of age among infants born very prematurely who received care based on the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP). Early Hum Dev. 2002;68:83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kleberg A, Hellstrom-Westas L, Widstrom A-M. Mothers’ perception of Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) as compared to conventional care. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83:403–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fawcett LM, Garton AF. The effect of peer collaboration on children’s problem-solving ability. Br J Educ Psychol. 2005;75:157–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sood E, Berends WM, Butcher JL, Lisanti AJ, Medoff-Cooper B, Singer J, et al. Developmental Care in North American Pediatric Cardiac Intensive Care Units: Survey of Current Practices. Adv Neonatal Care. 2016;16:211–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Butler SC, Huyler K, Kaza A, Rachwal C. Filling a significant gap in the cardiac ICU: implementation of individualised developmental care. Cardiology in the young. 2017;27:1797–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Santos J, Pearce SE, Stroustrup A. Impact of hospital-based environmental exposures on neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants. Current opinion in pediatrics. 2015;27:254–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Symington A, Pinelli J. Developmental care for promoting development and preventing morbidity in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD001814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Montirosso R, Del Prete A, Bellu R, Tronick E, Borgatti R, Neonatal Adequate Care for Quality of Life Study G. Level of NICU quality of developmental care and neurobehavioral performance in very preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1129–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Coughlin M, Gibbins S, Hoath S. Core measures for developmentally supportive care in neonatal intensive care units: theory, precedence and practice. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65:2239– 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Moody C, Callahan TJ, Aldrich H, Gance-Cleveland B, Sables-Baus S. Early Initiation of Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) Reduces Length of Stay: A Quality Improvement Project. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Als H, Duffy FH, McAnulty G, Butler S, Lightbody L, Kosta S, et al. NIDCAP improves brain function and structure in preterm infants with severe intrauterine growth restriction. J Perinatol. 2012;32:797–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sannino P, Gianni ML, De Bon G, Fontana C, Picciolini O, Plevani L, et al. Support to mothers of premature babies using NIDCAP method: a non-randomized controlled trial. Early Human Development. 2016;95:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Nelson AM, Bedford PJ. Mothering a preterm infant receiving NIDCAP care in a level III newborn intensive care unit. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2016;31:e271–e82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]