Abstract

Rationale:

Implementation of electronic health records may improve the quality, accuracy, timeliness, and availability of documentation. Thus, our institution developed a system that integrated EEG ordering, scheduling, standardized reporting, and billing. Given the importance of user perceptions for successful implementation, we performed quality improvement study to evaluate electroencephalographer satisfaction with the new EEG Report System.

Methods:

We implemented an EEG Report System that was integrated in an electronic health record. In this single-center quality improvement study, we surveyed electroencephalographers regarding overall acceptability, report standardization, workflow efficiency, documentation quality, and fellow education using a 0-5 scale (5 was best).

Results:

Eighteen electroencephalographers responded to the survey. The median score for recommending the overall system to a colleague was 5 (range 3-5) indicated good overall satisfaction and acceptance of the system. The median scores for Report Standardization (4; 3-5) and Workflow Efficiency (4.5; 3-5) indicated that respondents perceived the system as useful and easy to use for documentation tasks. The median scores for Quality of Documentation (4.5; 1-5) and Fellow Education (4; 1-5) indicated that while most respondents believed the system provided good quality reports and helped with fellow education, a small number of respondents had substantially different views (ratings of 1).

Conclusions:

Overall electroencephalographer satisfaction with the new EEG Report System was high, as were scores for perceived usefulness (assessed as standardization, documentation quality, and education) and ease of use (assessed as workflow efficiency). Future study is needed to determine whether implementation yields useful data for clinical research and quality improvement studies or improves EEG report standardization.

Keywords: EEG, Reporting, Electronic Medical Record, Technology Adoption

Introduction

Electronic Health Record (EHR) implementation has been shown to improve clinical documentation quality, accuracy, timeliness, and availability.1-3 Given these advantages, there have been recent efforts to integrate electroencephalography (EEG) reports within EHRs to make them more readily available to referring clinicians, enable standardized reporting, and integrate EEG workflow components including scheduling, reporting, billing, and report delivery. However, literature outside of the EEG domain identified healthcare provider reluctance as an important barrier to transition to EHR based systems,4 thereby leading to challenges related to information access, completeness, timeliness, and communication.2; 3; 5; 6 Prior studies and the Technology Acceptance Model indicate that clinician use and documentation completeness are impacted by user satisfaction, and user satisfaction is impacted by users’ assessments of the technology’s usability and usefulness.1; 3; 7-9 Given these data, when our institution developed and implemented a new EEG EHR System that integrated inpatient and outpatient workflow encompassing EEG orders, scheduling, electroencephalographer notification, standardized reporting, billing, report delivery, and report integration into clinical notes, we performed a quality improvement study to evaluate electroencephalographer satisfaction.

Methods

Study Setting

The study was performed at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia which is a tertiary care institution providing comprehensive inpatient and outpatient care. The institution has 26 electroencephalographers. The EEG Lab employs 22 registered EEG Technologists who provide around-the-clock in-house inpatient coverage for an Epilepsy Monitoring Unit and Critical Care EEG Monitoring Service, a main site EEG Lab, eight satellite EEG locations, and several affiliate hospitals. The institution uses the Epic EHR (Verona, WI) for most inpatient and outpatient clinical documentation, lab results, and procedure reports.

EEG EHR System

Prior to this quality improvement project, EEG reports were generated as Microsoft Word documents which were subsequently pasted into the EHR or within EEG software which generated a PDF document that was transferred through an interface to the EHR. As part of a quality improvement project led by the Information Systems Department, we aimed to develop and implement a new integrated EEG EHR System. The project involved an inter-disciplinary team including representatives from Neurology (physician), EEG Lab (physician, EEG Technologists, managers, coordinators), Information Technology (Epic Systems Analyst), and Billing and Compliance. An Epic Systems Analyst guided the system build, testing, and setup. Electroencephalographers received training on the new system using in-person sessions, a brief reference guide with many screenshots, and a brief video showing the new reporting workflow. Additional assistance during go-live was provided by an Epic Systems Analyst, the EEG Lab Director, and EEG Fellows who quickly became experienced super-users. Initial implementation occurred in January 2018. In January 2019 we made minor modifications based on feedback related to text formatting and spelling errors, but the overall structure and content remained unchanged.

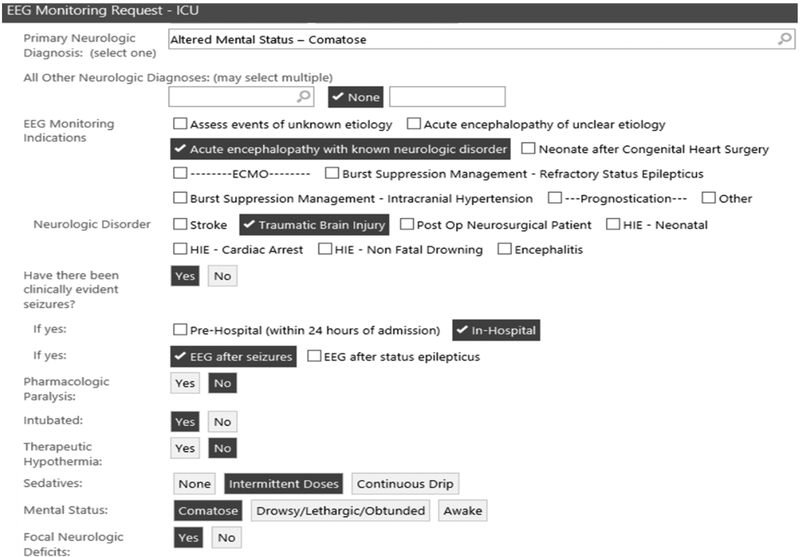

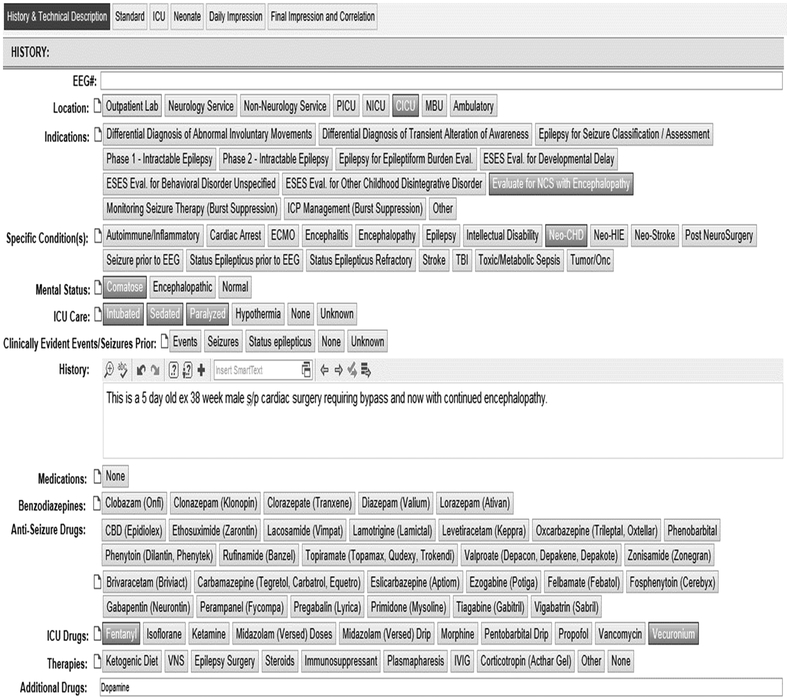

The Epic process for EEGs starts with an order for a routine EEG, four-hour EEG, ambulatory EEG, or inpatient EEG monitoring (Figure 1). When the order is signed, it is automatically sent to the appropriate scheduling workqueue so coordinators and nurses can faciliate the outpatient EEG procedure appointments or the inpatient pre-admission. The order is linked to the appointment or pre-admission so clinical information contained in the order is easily available to the care team. Upon patient arrival, the order automatically activates which sends the patient’s demographic information through an interface to the Natus Neuroworks EEG System and places the patient on an Epic “Ongoing EEG“ worklist. The EEG Technologist performes the EEG and uses the EHR worklist to access the patient visit, enter clinical and technical information (Figure 2a), assign an electroencephalographer, and enter associated charges.

Figure 1.

Order for Inpatient EEG Monitoring.

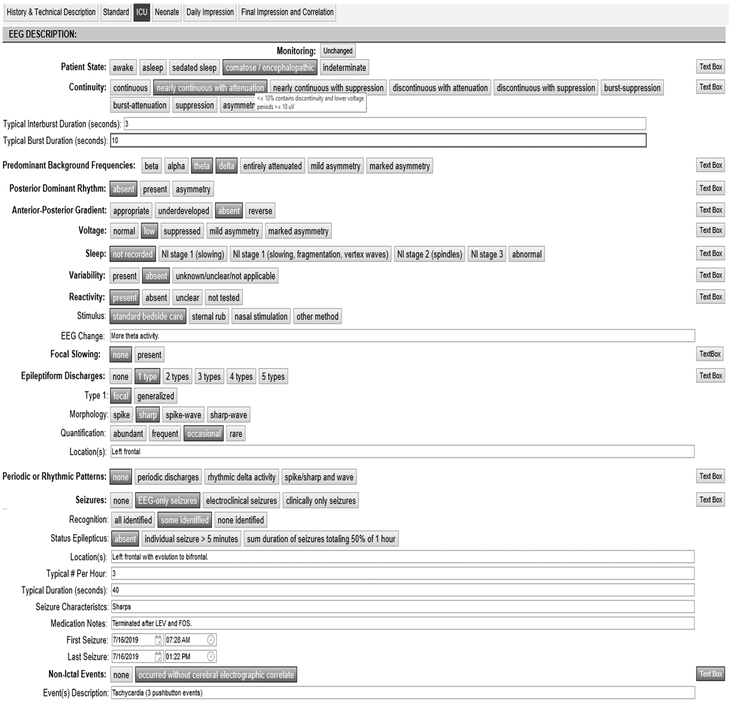

Figure 2.

Reporting Display using the ICU EEG Palette.

2a. History and Technical Description fields.

2b. ICU EEG Report fields.

2c. Compiled final report.

When the EEG Technologist completes the study and appointment, the assigned electroencephalographer receives an inbasket notification that the study is ready to interpret. The provider selects the message which opens the result documentation tool. Providers can document using three different reading palettes (Standard, ICU, Neonate) which have standardized report components and use terminology recommended by the American Clinical Neurophysiology Society10-12 as well as free text fields (Figure 2b). When a user hovers a cursor over many buttons, explanatory text displays definitions and categories based on the standardized terminology. The providers use palette buttons and text fields on their left of the monitor and can see the compiled report they are generating on the right side of the monitor. The reporting palettes are built using Epic SmartForms which allows buttons to import text phrases into the report. Screenshots of EEG can be pasted into a designtated field for future reference. When fellows are involved in reporting, their draft reports are routed to the attending for editing and attestation, and attendings can perform attestation using a single button.

Hospital charges are submitted when an EEG Technologist marks the study complete while physician charges are submitted when the attending physician marks the report as final. A final report (Figure 2c) is routed to the ordering provider’s “results“ inbasket folder and becomes immediately available in the Procedures section of the EMR. Epic dotphrases allow providers to import the impression section text from the most recent EEG or most recent five EEGs into inpatient or clinic progress notes. Coordinators can audit the schedules to ensure documentation is complete, charges are submitted, and the visits are complete. Administrators can use pre-built forms to access data regarding EEG characteristics, locations, volume, and billing. Additionally, clinical data entered using the report template is coded and can be exported as needed for quality improvement or clinical research studies.

Quality Improvement Study

In February 2019 we performed a survey of all electroencephalographers regarding their perceptions of a new EEG Report System. The study was not reviewed by the Institution Review Board since it was designed and conducted as an operational quality improvement study. No personal identifiers were collected, and respondents had two weeks to complete the survey. We developed a simple data collection instrument based on the Technology Acceptance Model9 which theorizes that system acceptance and utilization are predicted by ease of use and perceived usefulness. We shortened the full instrument to optimize clinician completion of the survey and modified the wording to reference the EEG EHR System. We report descriptive statistics for respondent demographics and each of the survey questions, and we plotted respondent satisfaction responses to evaluate the spread and symmetry of the responses. We used the SQUIRE 2.0 guidelines to guide project development and publication.13; 14

Results

Data were collected from 18 respondents out of 26 electroencephalographers surveyed (69% response rate). Respondents had been in practice 1-5 years (11; 61%), 6-10 years (1; 6%), 11-25 years (4; 22%), and >25 years (2; 11%). Sixteen respondents (89%) completed an EEG or Epilepsy Fellowship, and 16 respondents were involved in training EEG-Epilepsy Fellows. Respondents interpreted and reported routine (18; 100%), ambulatory (16; 89%), and Epilepsy Monitoring Unit (16; 89%) EEG. Sixteen respondents interpreted and reported EEG from their own patients and other clinicians’ patients while two interpreted and reported EEG for only their own patients.

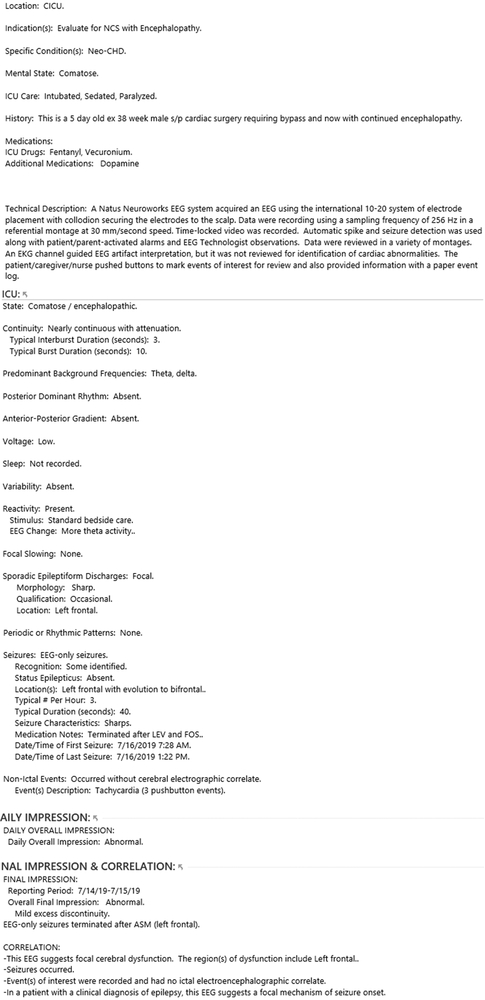

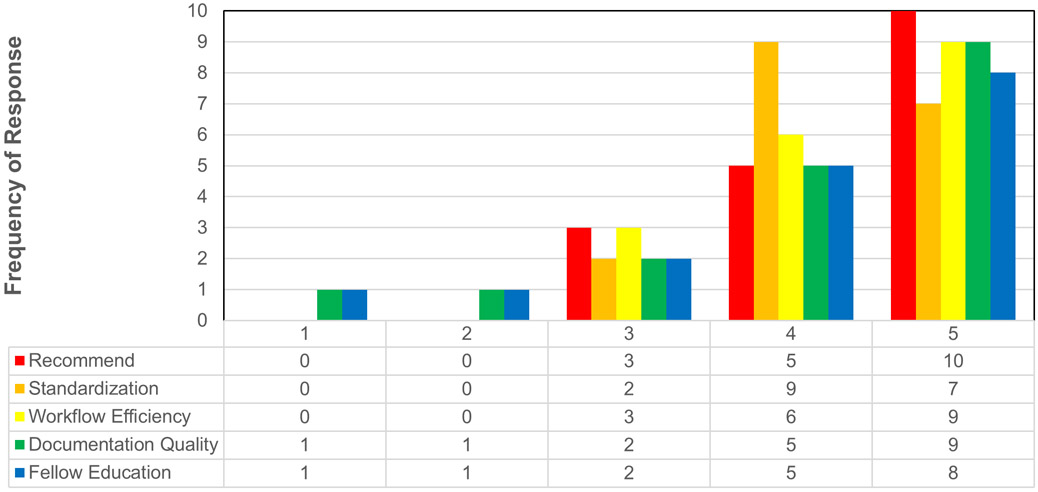

Figure 3 provides the response frequencies. The median score for recommending the overall system to a colleague was 5 (range 3-5), indicating good overall satisfaction and acceptance of the EEG Report System. The median scores for Report Standardization (4; 3-5) and Workflow Efficiency (4.5; range 3-5) indicated that respondents perceived the system as useful and easy to use for documentation tasks. The median scores for Quality of Documentation (4.5; range 1-5) and Fellow Education (4; range 1-5) indicated that while most respondents perceived the system to provide good quality reports and help with fellow education, a small number of respondents had substantially different views (ratings of 1). Quotes from some respondents providing low ratings focused on two themes. Regarding documentation quality, there was some concern that information might be lost using the standardized reporting fields. For example, respondents described that “less rich narrative description makes report less readable” and “forms are easier, but information is lost.” Regarding fellow education, there was some concern that standardized fields reduced consideration of the overall content. For example, one respondent described that “improved efficiency and what to report, but fellows can mindlessly click buttons without thinking about meaningful components.” The same two respondents provided low ratings (1-2) for Quality of Documentation and Fellow Education.

Figure 3.

Response frequency for each assessment domain.

Discussion

Recent systematic reviews and data from outside the EEG domain indicate that EHR adoption can improve the quality of patient care, increase access to patient care data, and enhance documentation organization, accuracy, completeness, and consistency. However, these gains only occur if users adopt the new technology. More consistent technology utilization by clinicians occurs with higher user satisfaction, which in turn is driven by perceived usefulness and ease of use of the technology.1; 3; 8; 15-20 Clinicians need efficient time management, making ease of use and perceived usefulness critical. Thus, an EEG Report System that provides point-and-click documentation, is easy to navigate, and provides real-time definitions for key EEG variables could be key to optimizing user acceptance. Our inter-disciplinary development team aimed to determine the acceptability of a new EEG Report System by measuring users’ satisfaction. Overall satisfaction with the new system was high, as indicated by a median score of 5 out of 5 for recommending the system to a colleague. Scores were also high for perceived usefulness (assessed as standardization, documentation quality, and education) and perceived ease of use (assessed as workflow efficiency).

Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation, a theoretical framework for implementation systems, suggests that the decision to adopt a new technology involves knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation. Technology is more likely to be adopted if it is perceived by users to be better, consistent with their needs, simple to use, and provides visible results.21 Relatedly, Davis’ Technology Acceptance Model proposes that the two factors leading to technology adoption are perceived usefulness (reflecting an individual’s belief that the system improves performance) and ease of use (reflecting that use of the new system is stress free).1; 9 Prior studies outside the EEG domain indicate that user perceptions greatly influence user satisfaction,8; 19 and a recent literature summary focused on the Technology Assessment Model concluded it was appropriate for use in design, training, and implementation processes related to information technology.1 Our data indicate that an EEG Report System was perceived as both useful and easy to use.

Despite the generally good assessments by users, there was variability with two respondents provided low ratings (1-2) for both Quality of Documentation and Fellow Education. This variability is important in considering subsequent modifications. Outliers could relate to numerous factors such as training, individual values and beliefs, prior experiences with similar technologies, existing ideas, and change motivation. Some individual personality traits are associated with perceived ease of use (optimism, innovativeness) and perceived usefulness (optimism and positive attitude toward technology).22 However, the criticisms may also offer useful insights into subsequent optimization modifications. Although the report templates offered free text fields, some users with outlier responses indicated that they couldn’t optimally describe the EEG and were concerned information was being lost. Future iterations may need to modify the standardized variable fields or emphasize the availability of free text fields to be used when necessary.

Clinical documentation is important for provision of care, and EHR integration may be useful for several reasons. First, EEG may provide important immediately actionable data, but old EEG data may also meaningfully impact later management. EHR integration ensures EEG data is both rapidly accessible to users across the institution and easy to locate at later times. Second, many users of EEG data rely on the overall interpretation and clinical correlation. Report standardization may enhance use of common terms and formats which become familiar to clinicians referring patients for EEG studies. Third, given recommendations regarding EEG report components and standardized terminology for some settings, such as critical care EEG,10 standardized report templates may be needed to provide users with real-time access to sometimes complex variable definitions.

As the inter-disciplinary team selected design elements, we focused extensively on creating a structure and workflow which would enhance acceptability by optimizing ease of use. The team understood that the final product needed to be acceptable to a wide range of electroencephalographer users, ranging from EEG specialists performing work in the Epilepsy Monitoring Unit to busy outpatient clinicians reporting EEGs during clinic. A mantra became “reduce button clicks” as we recognized that seemingly small additional data fields or reporting inefficacious could substantially impact ease and efficiency of use when all combined in the final product. Several aspects of the design illustrate key decisions made to balance data completeness with ease of use. For example, we considered carefully the optimal workflow when the EEG was unchanged over subsequent days. A design feature of the EHR system precluded “pulling forward” previously entered data for reports, unlike the process available for clinical notes. Additionally, we expected that end users might want to rapidly identify changes over multi-day studies, rather than having to search for changes amid large amounts of unchanged data. We a result, we included a “Monitoring Unchanged” button (top of Figure 2). As part of the workflow, when the button was used to avoid re-entering unchanged data in the body of the report, electroencephalographer would still enter the full Impression text at the end of the report. A recent update to the EHR now allows “pull forward” within reports, and our institution is considering whether to implement this feature as part of a subsequent revision. As a second example, since each data field was a unique data element, we built macros which could complete numerous discreet data fields using a single macro button. Thus, an electroencephalographer could efficiently use a single button (i.e., “normal teen awake”) to enter complete numerous discreet data fields.

There are several important limitations to this study. First, the study was conducted at only one center with an EHR already used for most inpatient and outpatient work. Thus, it is unclear whether the data are generalizable to other settings, particularly if an EHR is only partially implemented or clinicians have only have limited experience with the EHR. Second, there was extensive training and end-user support during implementation, and it is uncertain how this go-live approach impacted user perceptions regarding the technology. Third, most respondents knew the implementation study team members well, and these personal relationships and knowledge regarding the extensive work required to implement the system may have impacted respondents’ assessments. Fourth, we did not use the full Technology Assessment Model assessment questions to keep our assessment very brief. However, future iterations of this type of implementation assessment could benefit from utilization of the full questionnaire to optimally link the model. Finally, this study focused exclusively on electroencephalographer acceptance of the report system. The project covered a much larger scope (including scheduling, billing, and report distribution), but other aspects were generally assessed in a simpler and more binary manner. The scheduling component was quickly deemed effective and efficient by the EEG Lab coordinators, billing was found to be accurate and timely by managers and billing-compliance staff, and EEG ordering was considered consistent with the typical order process used by clinicians for most procedures. We did not survey end users of the EEG report regarding their acceptance of the new report format.

Future studies are needed regarding several concepts. First, the standardized EEG report data can be easily integrated into inpatient and clinic notes, but the impact of these standardized and readily available data on clinical care is uncertain. Second, provision of standardized EEG variables including embedded definitions for some variables could yield standardization and increased inter-rater agreement across electroencephalographers, although further study is needed to determine whether this inter-rater agreement enhancement is achieved. Third, collection of standardized EEG data which can be exported from the EHR should make EEG related clinical research and quality improvement studies more feasible, although such studies have not yet been completed to evaluate this approach. However, given that our current data indicate high user perceptions of usefulness and ease of use, there is likely substantial promise in further developing and refining EEG EHR Systems.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Abend is funded by NIH K02NS096058.

Footnotes

None of the authors have other conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Holden RJ, Karsh BT. The technology acceptance model: its past and its future in health care. J Biomed Inform 2010;43:159–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coffey C, Wurster LA, Groner J, et al. A comparison of paper documentation to electronic documentation for trauma resuscitations at a level I pediatric trauma center. J Emerg Nurs 2015;41:52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen L, Bellucci E, Nguyen LT. Electronic health records implementation: an evaluation of information system impact and contingency factors. Int J Med Inform 2014;83:779–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ajami S, Bagheri-Tadi T. Barriers for Adopting Electronic Health Records (EHRs) by Physicians. Acta Inform Med 2013;21:129–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grigg E, Palmer A, Grigg J, et al. Randomised trial comparing the recording ability of a novel, electronic emergency documentation system with the AHA paper cardiac arrest record. Emerg Med J 2014;31:833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keenan G, Yakel E, Dunn Lopez K, et al. Challenges to nurses' efforts of retrieving, documenting, and communicating patient care information. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013;20:245–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry JJ, Sutherland J, Symington C, et al. Assessment of the impact on time to complete medical record using an electronic medical record versus a paper record on emergency department patients: a study. Emerg Med J 2014;31:980–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al Alawi S, Al Dhaheri A, Al Baloushi D, et al. Physician user satisfaction with an electronic medical records system in primary healthcare centres in Al Ain: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis FD. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly 1989;13:319–340. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirsch LJ, LaRoche SM, Gaspard N, et al. American Clinical Neurophysiology Society's Standardized Critical Care EEG Terminology: 2012 version. J Clin Neurophysiol 2013;30:1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuchida TN, Wusthoff CJ, Shellhaas RA, et al. American Clinical Neurophysiology Society Standardized EEG Terminology and Categorization for the Description of Continuous EEG Monitoring in Neonates: Report of the American Clinical Neurophysiology Society Critical Care Monitoring Committee. J Clin Neurophysiol 2013;30:161–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tatum WO, Olga S, Ochoa JG, et al. American Clinical Neurophysiology Society Guideline 7: Guidelines for EEG Reporting. J Clin Neurophysiol 2016;33:328–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, et al. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. Am J Med Qual 2015;30:543–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman D, Ogrinc G, Davies L, et al. Explanation and elaboration of the SQUIRE (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence) Guidelines, V.2.0: examples of SQUIRE elements in the healthcare improvement literature. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeh SH, Jeng B, Lin LW, et al. Implementation and evaluation of a nursing process support system for long-term care: a Taiwanese study. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:3089–3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carayon P, Cartmill R, Blosky MA, et al. ICU nurses' acceptance of electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:812–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirkendall ES, Goldenhar LM, Simon JL, et al. Transitioning from a computerized provider order entry and paper documentation system to an electronic health record: expectations and experiences of hospital staff. Int J Med Inform 2013;82:1037–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau F, Kuziemsky C, Price M, et al. A review on systematic reviews of health information system studies. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2010;17:637–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holden RJ, Asan O, Wozniak EM, et al. Nurses' perceptions, acceptance, and use of a novel in-room pediatric ICU technology: testing an expanded technology acceptance model. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2016;16:145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones NT, Seckman C. Facilitating Adoption of an Electronic Documentation System. Comput Inform Nurs 2018;36:225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations (5th Edition). The Free Press: New York, NY; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuo KM, Liu CF, Ma CC. An investigation of the effect of nurses' technology readiness on the acceptance of mobile electronic medical record systems. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]