Abstract

Background:

While the occurrence of food cravings during pregnancy is well-established, there is a paucity of qualitative data on pregnant women’s perceptions of and responses to food cravings. This study sought to assess and describe pregnant women’s experiences and behaviors pertaining to food cravings.

Methods:

Eight focus groups were conducted with 68 pregnant women in their second trimester from March 2015 to October 2016. Using a semi-structured approach, the facilitator asked women open-ended questions regarding their experience of eating behaviors and food cravings. The content from the focus groups was analyzed using a bottom-up approach based on grounded theory and constant comparison analysis.

Results:

Participants described cravings as urgent, food-specific, and cognitively demanding occurrences that were differentiated from hunger. They described beliefs surrounding the physiological causes of cravings and rationales for satisfying their cravings. Strategies used to manage cravings included environmental modifications to limit proximity and availability of craved foods, cognitive and behavioral strategies like distraction, and acceptance through satisfying the craving. Participants described food cravings as a psychologically salient aspect of their pregnancy, reporting a variety of emotional precursors and reactions surrounding their cravings.

Conclusions:

A better understanding of food cravings may assist with the development of interventions to improve eating behaviors and reduce eating-related distress during pregnancy. Acceptance regarding food cravings was indicated as a way to diffuse pregnancy-related stress. These findings contribute to our understanding of psychological influences on eating behaviors in pregnant women.

Keywords: Pregnancy, food cravings, eating behavior, strategies

Introduction

Food cravings, defined as intense desires for specific foods that are difficult to resist,1–3 are common during pregnancy,4 when diet has important implications for a variety of maternal and infant health outcomes.5–10 Food cravings during pregnancy are associated with increased intake of discretionary foods,4,11 and with excess gestational weight gain.4,12–14 Understanding women’s interpretations and behaviors related to food cravings in pregnancy may inform efforts to improve eating behaviors and weight trajectories during this developmental period in a woman’s life.

Food cravings are present early in pregnancy, with peak frequency occurring during the second trimester.15–17 In interviews and focus groups examining perceived influence on diet and weight gain during pregnancy, food cravings were said to influence food choices and were identified as a common barrier to healthy eating.18,19 Additionally, women perceived these cravings as biologically based and therefore out of their control.20 Specific foods craved are culture- and context-specific, but in the U.S. and other western countries, cravings commonly include comfort foods such as ice cream, chocolate, fruits, and other sweets.13,16,21,22 However, given cultural and contextual influences on the experience of food cravings in the general population,23–26 much of the research on food cravings during pregnancy conducted more than a decade ago may not be applicable to contemporary samples of pregnant women.

While previous research has documented the frequency of cravings and explored types of foods craved, there is a paucity of qualitative data on pregnant women’s responses to food cravings and strategies for managing them. Some women have reported initiating healthier eating behaviors as a way to regain power in response to a perceived loss of control over pregnancy-related physical and physiological changes.27 However, eating behaviors in general have been identified as contributing to feelings of guilt and negative affect during pregnancy, as many women are aware that certain foods such as alcohol, raw fish, or processed foods may be harmful to the baby.27 Some women indicated that their perception of the importance of a healthy diet for themselves and their fetus contributed to attributions of being a “good mother” when consuming healthy foods, and a “bad mother” when consuming what they considered to be unhealthy foods, furthering feelings of guilt and distress over lack of self-control.20 These findings suggest a role of dietary issues in influencing psychological well-being in pregnancy; however, little is known about the emotional impact of food cravings in pregnant women. Qualitative research is particularly well suited for in-depth exploration of dietary behaviors in the context of lived experience28, and thus is a useful methodology for advancing understanding of women’s perceived experience of cravings. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to qualitatively assess and describe women’s interpretations and perceptions of their experiences, behaviors, and coping strategies pertaining to food cravings during pregnancy.

Methods

Participants

Focus group participants were a subsample of participants of the Pregnancy Eating Attributes Study (PEAS), an observational, prospective cohort study examining the associations of food reward sensitivity with pregnancy-related diet and weight change.29 PEAS participants were recruited from the obstetrics clinics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Healthcare System. Details on enrollment and recruitment of PEAS are described elsewhere.29 Eligibility criteria included: gestational age <12 weeks, aged 18-45 years, no previous diagnosis of psychiatric or eating disorders, no medical conditions or medications that would affect participation in the study or that could affect diet and weight. Demographic data was collected on PEAS participants prior to entrance into the focus group study. Focus group participants were recruited between 15 and 27 weeks gestation across the range of early pregnancy BMI, including only participants who completed at least 75% of baseline surveys. All focus groups were conducted between March 2015 and October 2016.

Procedures

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Respondents were informed of the nature and purpose of the study, provided written informed consent prior to participation and were compensated $50 in cash for their participation.

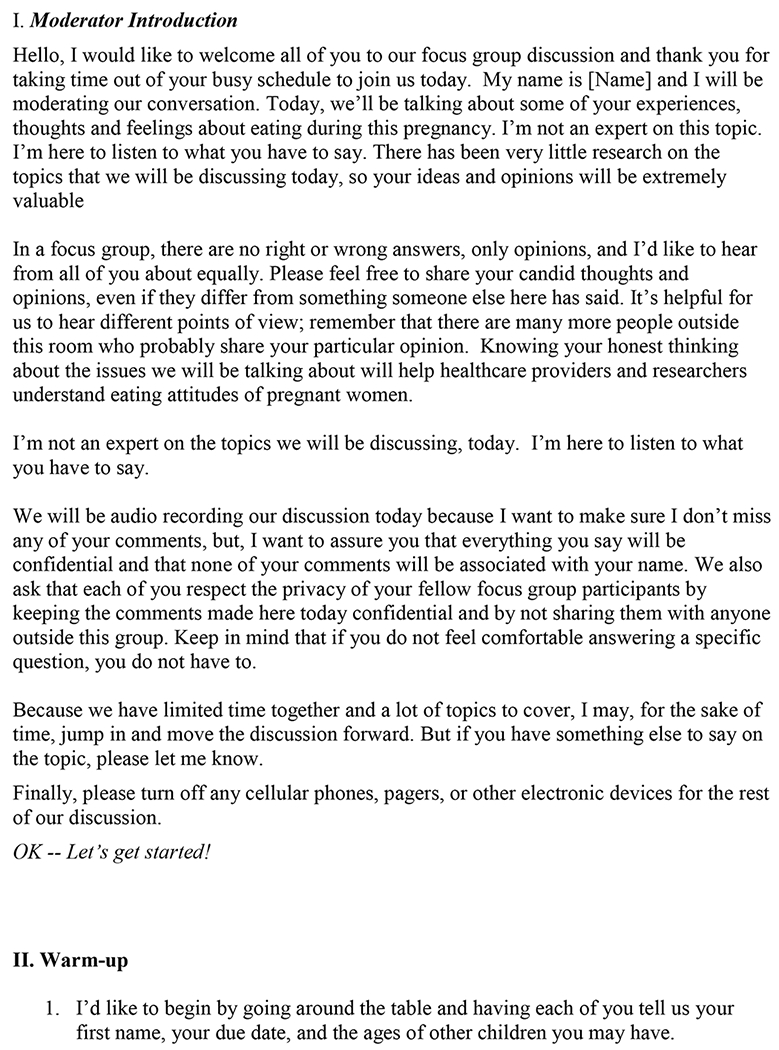

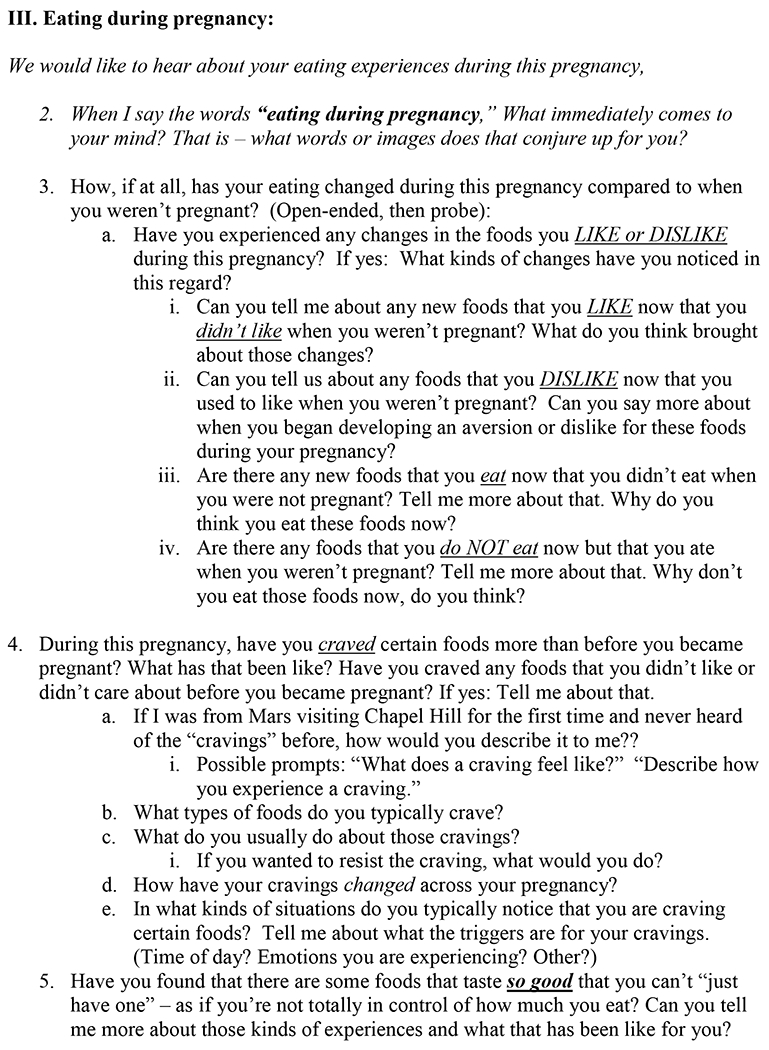

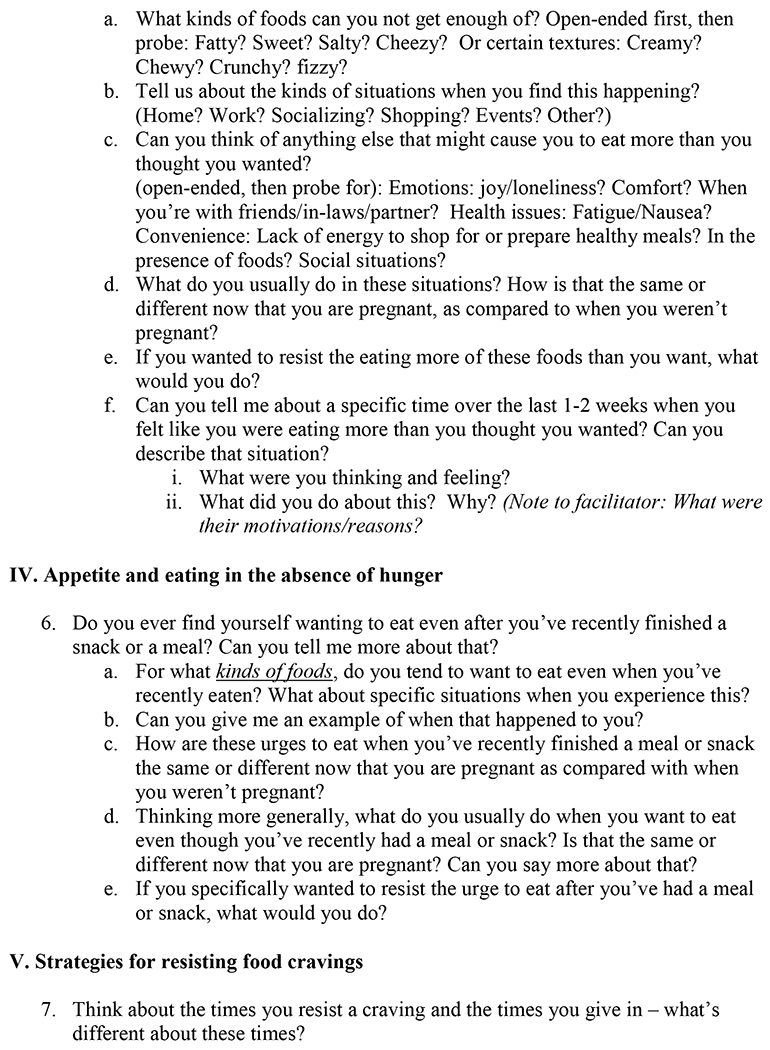

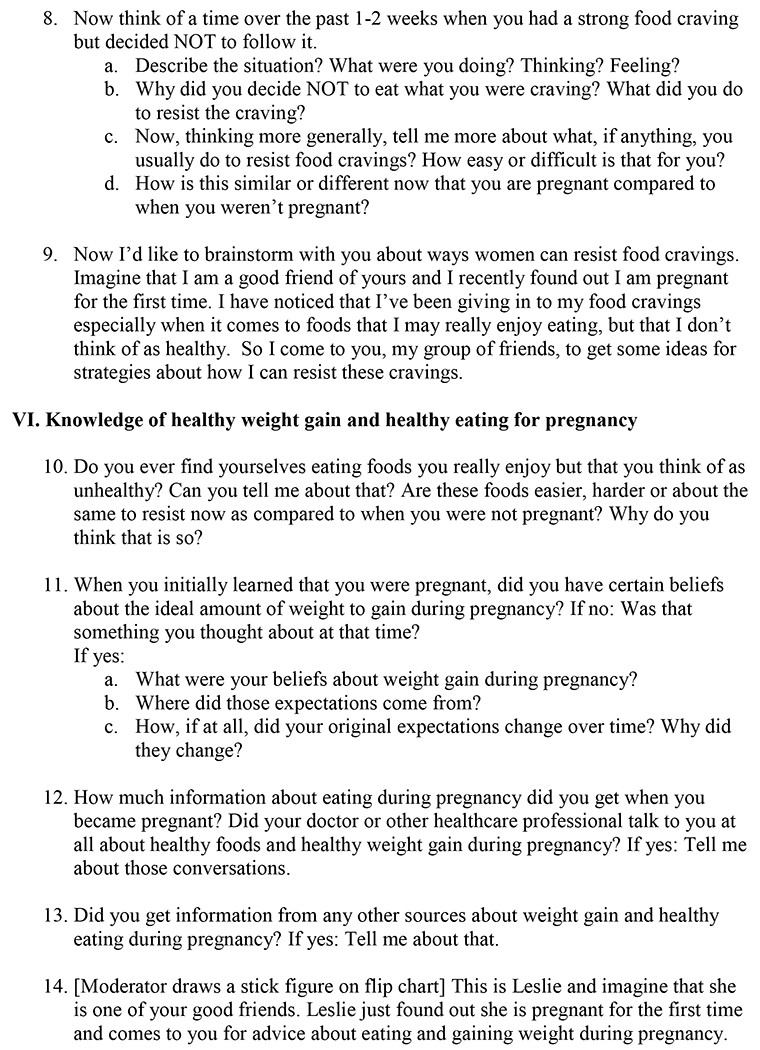

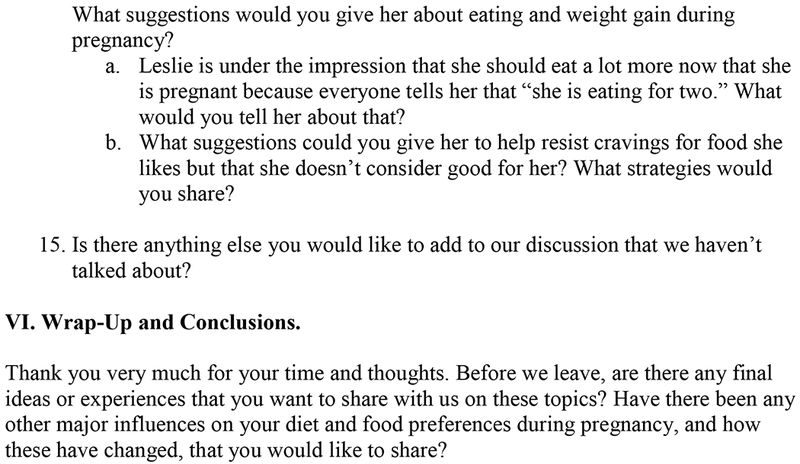

Focus groups were facilitated by a female moderator with expertise in conducting focus groups. They were held in a conference room at the Women’s Health Research Center, where refreshments and childcare were provided. The facilitator explained the importance of everyone’s opinion being heard, noting that the goal was to gather different perspectives and to hear the women’s voices on certain topics. The facilitator also emphasized the importance of confidentiality and underscored that there were no ‘right or wrong answers’ in focus groups. Participants were asked open-ended questions regarding eating behaviors and experiences of cravings in pregnancy, with follow-up prompts used as needed to facilitate discussion (Figure 1). Focus group questions were developed by a team of investigators with expertise in dietetics, reproductive epidemiology, nutrition, and clinical, community, and developmental psychology. Questions were subsequently reviewed and refined in consultation with the focus group facilitator to ensure plain language, clarity, and avoidance of leading language. Each focus group lasted 60–90 minutes and was audio recorded and transcribed thereafter. At least one study investigator and an additional note taker attended every focus group. Eight focus groups with 5-14 participants in each were conducted over the course of a year. Data saturation was not formally determined; however, previous research suggests the adequacy of this sample for data saturation. In studies examining the contribution of more than 40 focus groups,30 data saturation was reached after five focus groups, and 90% of themes were discoverable within 3–6 focus groups, with 3 focus groups sufficient to identify all the most prevalent themes31.

Figure 1:

The discussion guide used with a focus group cohort of 68 women in North Carolina participating in the Eating Attributes Study regarding women’s perceptions, beliefs, and experiences about eating during pregnancy

Analysis

Focus group content was analyzed using Nvivo 11 following established guidelines.28,32,33 The coding scheme was developed using data from all eight focus groups. Five authors independently evaluated one transcript for initial theme development and discussed the resulting codes to obtain consensus. Using a bottom-up approach from grounded theory, each topic that arose in the focus groups was noted and then categorized into major themes. Using constant comparison analysis,34 content from each group was subsequently reviewed to identify themes and determine whether themes from one group emerged across other groups. The remaining transcripts were then reviewed and the thematic framework was refined to incorporate data from all eight focus groups. A peer-debriefing process was then used to reach consensus on the coding scheme. Two authors independently coded each transcript and then reviewed with research team members to reconcile any discrepancies. Coding was modified as needed based on emerging constructs. Results are categorized by themes reflecting topics that were explicitly queried in the guide - “a priori,” and themes that emerged without questions that specifically addressed them - “emergent.”

Results

Table 1 describes the demographics of the focus group sample in comparison to the main study population. The majority of focus group participants were non-Hispanic white and had a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Table 1.

Demographics of a cohort of 68 pregnant women from North Carolina participating in focus group data collection on food cravings in pregnancy.

| Demographics | PEAS Study Full Sample N=458 | Focus Group Sample N=68 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30.5±4.7 | 31.3±4.2 |

| Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 264 (67.3) | 50 (74.6) |

| Racial/ethnic minority | 128 (32.7) | 17 (25.4) |

| Education | ||

| Less than bachelor’s | 104 (28.4) | 12 (18.4) |

| Bachelor’s | 108 (29.4) | 26 (40.0) |

| Greater than bachelor’s | 155 (42.2) | 27 (41.6) |

| Income-to-poverty ratio | 3.8±2.0 | 4.1±1.8 |

| BMI | 27.2±6.9 | 25.8±5.8 |

| Parity | ||

| Nulliparous | 250 (54.6) | 33 (48.5) |

| Parous | 208 (45.4) | 35 (51.5) |

Values are mean±SD or n (%)

PEAS= Pregnancy Eating Attributes Study

BMI= Body Mass Index,(kg/m2)

Themes

Six themes were identified surrounding the experience of food cravings in pregnancy. Three related to questions asked explicitly by the facilitator: (1) descriptions of cravings; (2) types of foods craved (3) strategies for managing cravings. Additional themes were identified that emerged organically during the focus groups: (4) beliefs about the cause of cravings; (5) justifications for satisfying cravings; and (6) psychological aspects of cravings.

A priori themes

Descriptions of cravings

See Table 2 for representative quotes from the focus group study regarding women’s experience with cravings in pregnancy. Participants described cravings as an intense, food-specific, and all-consuming desire for a certain food. Cravings occurred at various times of the day and night, and were generally differentiated from hunger. Some of the women described cravings as transient, while many said the feeling was consistently powerful until satisfied. One aspect of cravings consistent across women was the specificity of the food craved; in many cases, even the brand or restaurant name was specified.

Table 2.

Representative quotes regarding women’s experience with food cravings from a qualitative focus group sample of 68 women from North Carolina.

| A priori Themes | Selective Quotes |

|---|---|

| Descriptions of Cravings | “It’s all you can think about.” “You just have to have it right then.” |

| “Like, in the first pregnancy, I’m, like, oh man, I can eat twice as much. But, I know that’s not true anymore. But, I still, like, it’s, like, my brain says one thing and my heart says one thing - and my heart always wins. And, I, I don’t like that but it’s just, that’s what I want is what I want and I get cranky if I don’t have what I want when I’m pregnant.” | |

| “…When you’re really hungry and you really want to eat only you’re not necessarily really hungry you just really want to eat that very specific thing.” | |

| “Mine tend to pass. If I wait long enough. If..I can’t go get it, for whatever reason, and I wait a few hours, then eventually. I don’t care for it anymore.” | |

| “I’ll crave it for days. Until I get it.” | |

| “I didn’t eat nothing till he took me to go get my hamburger at Sonic, that’s what I wanted, I didn’t want nothing else, cause he’d be like, you don’t want to go to Chilies.no, I want that hamburger.” | |

| “Nothing is going to taste as good.” | |

| Types of Foods Craved | “And my husband will be drinking there, drinking beer. And I smell it, and I immediately, I’m like - oh my God.” |

| “I have been craving sushi…just the cooked kind, I mean… I haven’t been eating the raw fish kind but… I get a California roll as often as I can.” | |

| Strategies for Managing Cravings - Environmental | “Don’t buy it so it’s not in your house. Don’t pack it for lunch if you’re atwork, just don’t have it around.” |

| “I think that having your partner help you out and make good choices makes it easier, especially if like after dinner, they decide to have a piece of fruit rather than like ice cream or something, and you’re more likely to do the same.” | |

| “And it helps if there’s not anything sweet in the house. Obviously, it’s easier to just be like, well, go to bed.” | |

| “Our food is downstairs and the room we hang out in at night is upstairs and that is a pretty decent deterrent in itself. Not being close.” | |

| Strategies for Managing Cravings - Behavioral | “Say, like go for a walk, exercise, like exercise releases endorphins, and makes you feel good.” |

| “And so I usually just drink water, and rollover and go to sleep.” | |

| “I try not to let myself get really hungry. Like, plan a snack or a small meal every few hours so that - ‘cause I know that if I do get hungry, then I’m gonna go for something that’s not very good for me.” | |

| “I mean I guess if I’m craving sweets, I have a piece of fruit or something instead, see if that helps.” | |

| “Or just do it in moderation, like if you crave chocolate, don’t eat a chocolate cake… Try a piece of chocolate first and see how it goes.” | |

| “Sometimes all I’ll really taste is like a little lick and I’m OK. As long as I got it now.” | |

| Strategies for Managing Cravings -Psychological | “I don’t feel like I get them as much if I’m really busy.” |

| “I find just any interaction with my other child, forces you to forget about it, cause otherwise he’s just going run like into a ditch or something.” | |

| “Yeah, I think thinking about the baby helps, like when it’s something that’s really unhealthy or has like a whole lot of colorants or like caffeine or something else. You know, just thinking about the fact that, you know, not that’s it’s gonna do harm but just that, you know it’s not good for the baby.” | |

| “My giving into cravings or not is motivated by the health of my baby and what I look like” | |

| Strategies for Managing Cravings - Consumption | “Well, here’s the thing…I have a lot of pregnant friends right now and a lot of them are having the same issues I am, and…because this is my fourth pregnancy and I - each time, I’ve tried harder and harder but it doesn’t work. I just said, you know what, I’d rather give into my cravings than to beat myself up over it and hate myself for it.” |

| “That’s true if you deprive yourself of it, you’re just going to even want more later, so then instead of having the piece of chocolate cake, you’ll have the half of the chocolate cake.” | |

|

Emergent Themes Beliefs about the Causes of Cravings |

“I want milk, I mean my husband’s like, seriously woman, we’ve got to like every day we’re buying another gallon of milk, I said apparently I need it, but I’ve always liked, but I never drank it as much as I drink it now.…I guess she’s really developing some bones.” [referring to her baby] |

| “Cause like I’ve been eating ice cream like every day, but like I don’t really eat that much calcium, like I don’t drink milk or anything like that, so it’s like, okay, and that’s why I don’t really get too concerned about it, you know, cause I just feel like, okay this, if I’m craving this, there’s got to be a reason.” | |

| “Like I think I was drawn to the Raisin Bran, maybe for the iron or maybe something in it that my body knew was in that. And so I try to kind of pay attention to what am I craving and try, think about what is in that product that might be beneficial… ” | |

| Justifications for Satisfying Cravings | “I was like I just did prenatal yoga, I’m getting my sundae, it’s OK…Justified it.” |

| “Yesterday I had a burger, which I hadn’t had since before I got pregnant and for me, my excuse was I ate healthy during the week and I deserve eating something that’s not healthy.” | |

| “… I want to stay in shape, whatever. But, it’s like, oh, I’m pregnant, like, I can do this. I’m eating for two, so I kind of, like, rationalize it a little bit when I have that impulse to eat something.” | |

| “For me, being pregnant…society tells you, like, oh, you’re eating for two. Oh, you’re pregnant. And so when I have that urge…when I’m not pregnant, I can kind of fight that a little bit more.” | |

| “…is this [eating] pregnant-related or am I just allowing myself the indulgences that I didn’t, when I craved before?” | |

| “Well, I mean, I’ve gotten past the point where I know you’re not really eating for two.” | |

| “I think even, even a couple of us have made a joke about you’re eating for two, but I think in reality, that doesn’t translate into that, but it’s like, I’m going to justify this ice cream that I’m eating that I wouldn’t normally eat.” | |

| Psychological Aspects of Cravings | “Stressed out. Definitely when I’m stressed. I’m, like, I’m making myself some egg whites cookie dough… And it’s really bad but I just can’t stop myself from doing it. And it immediately takes my stress away.” |

| “Something that will put you just in an extremely bad mood or agitated if you don’t get it. Or extremely happy [when you do get it].” | |

| “Cravings are like intense. Like I have to have this now or I’m going to hurt someone… normally, I’d be like oh a cookie would be nice, but now it’s like, if I don’t get a hamburger, I’m gonna cry about it.” | |

| “I still feel guilty if I, you know, had too much. Maybe not as much as when I’m not pregnant but I still kind of feel like - oh, I shouldn’t, I shouldn’t have eaten that or what not.” | |

| “I have [used strategies to resist foods] on like diet plans but not when pregnant. I feel less guilty during pregnancy.” | |

| “I’d rather give into my cravings than to beat myself up over it and hate myself for it. You know what I mean?” | |

| “Stressing about it was making it worse, cause then I was obsessing over everything that I put in my mouth.” | |

| “I had a doctor tell me really early on, I had a lot of anxiety really early on, she was like if you want to eat something and it makes you feel better, the best thing that you can do is to not stress yourself out about it.” | |

| “It might be more nostalgic than anything, but I really wanted - I don’t eat a lot of processed foods but I really wanted Chef Boyardee ravioli.” | |

| “I think that’s part of it too for filling that craving, is that emotional need. Because I think that like I said with my ties with my Spanish root, I think it’s also the comfort factor, cause a lot of the times, my godmother were making that food and it reminds me of her.” |

Foods Craved

Participants primarily reported craving discretionary (“junk”) foods; some also indicated craving fruits. Some women craved specific meals like hamburgers from a fast-food restaurant, or a particular cuisine like Mexican food. Sweets and salty snack foods were commonly reported, with specific snacks including cheese puffs, chocolate, and potato chips. Additionally, some women reported craving items that they avoided consuming during pregnancy due to potential adverse health effects, such as deli meats, alcohol, and raw sushi. No participants indicating having cravings for non-food items (pica).

Strategies for managing cravings

Women described a variety of strategies for managing cravings. Four main sub-categories of coping strategies emerged from these discussions: contextual strategies, behavioral strategies, psychological strategies and satisfying cravings. Contextual strategies were usually related to removing craved foods from the environment or removing themselves from environments where they may encounter craved foods. The idea underlying this strategy was that if the food is not nearby, it would be easier to resist.

Women mentioned behaviorally-focused strategies, including eating frequently to prevent hunger, exercising, drinking water, and sleeping to help resist cravings. Another behaviorally-focused strategy was to substitute something healthier first, rather than start with the craved food, in an attempt to alleviate the urge. Alternatively, some consumed a small portion of the craved food.

Participants also described psychologically-based behavioral strategies including keeping busy or distracting themselves to mentally distance themselves from food cravings. More cognitively-focused psychological strategies for managing cravings included considering the health implications of the craved food for the baby.

The most common strategy reported was consuming the craved food item. This was often framed in terms of acceptance, as women felt that denying themselves the craved food caused psychological distress. Women stated that resisting the craved food was ineffective, and that the craving would intensify, causing them to eventually consume more of the craved food.

Emergent themes

Beliefs about the causes of cravings

Women’s beliefs about why cravings occur was an emergent theme as they discussed their experiences and behaviors surrounding the etiology of their cravings. Some women attributed the experience of cravings to physiological changes of pregnancy or requirements such as hormonal fluctuations or acute nutritional deficiencies.

Justifications for satisfying cravings

When participants discussed satisfying their cravings, they often provided a justification or rationale for this decision. Some women justified satisfying cravings as a reward for engaging in some other healthy behavior. Women also cited the additional pregnancy-related energy requirements as another justification for giving in to cravings. Several participants made statements suggesting they were aware that they may be using pregnancy as an excuse to eat an unhealthy food.

Psychological aspects of cravings

Women’s emotional triggers and responses were an emergent theme that occurred across participants’ discussions of experiencing, resisting, and satisfying cravings. Unpleasant emotional states prompted cravings for some women and resulted from resisting cravings for others. Both positive and negative emotional states were experienced in response to conceding to cravings. Some women experienced guilt for giving in to cravings, while others felt less guilty for giving in during pregnancy. Participants also described satisfying cravings in order to avoid psychological distress. Some women described cravings as arising from nostalgia or pleasant memories.

Discussion

In focus group discussions, pregnant women described cravings as highly salient experiences that they associate with their own eating behaviors and emotional experiences. They described cravings as urgent, food-specific, all-consuming occurrences that were differentiated from hunger. Consistent with previous findings,16,21 common types of foods craved by this sample of Western women were sweets such as chocolate and ice cream or salty foods like chips. 1 Women discussed their beliefs surrounding the physiological causes of cravings and described rationales for satisfying their cravings. Strategies used to manage cravings included environmental modifications to limit proximity and availability of craved foods, cognitive and behavioral strategies like distraction, and acceptance through satisfying the craving. These findings are consistent with strategies employed to manage cravings in non-pregnant populations.35,36 To our knowledge no previous research has examined strategies used by women during pregnancy to manage their cravings. Given the ubiquitous nature of cravings during pregnancy, these findings are important to help better understand psychological influences on eating behaviors in pregnant women.

Participants’ descriptions of justifications for indulging unhealthy cravings were often specific to pregnancy. Some women perceived cravings as reflecting a need for the specific nutrients present in the food, while others indicated a need to accept cravings as part of pregnancy to reduce feelings of distress. Consistent with previous research,37 a belief that pregnancy allowed for relaxed dietary rules was a reason to indulge in cravings. In a previous study, women who reported high levels of pre-pregnancy dietary restraint gained more gestational weight,38 suggesting the need for future research on the relationship between dietary restraint and food intake in pregnancy.

Emotional states were closely tied to women’s experiences of cravings. Participants indicated that positive and negative moods often preceded food cravings, and stated that resisting food cravings caused emotional distress, while indulging in cravings often precipitated a more positive mood state. This is consistent with research in non-pregnant populations in which food cravings are closely associated with mood39 and with the literature on emotional eating, which suggests that some people eat in response to a negative affective state.40 In pregnant women, food cravings have been shown to mediate the association of emotional eating with excess gestational weight gain41. Further, some women reported satisfying cravings because they associated the food with a positive emotion, such as a pleasant memory or feeling. Women reported responding emotionally to cravings in one of two ways - with guilt or with a sense of satisfaction and relief. Some women experienced both. Participants appeared to employ acceptance-related cognitive strategies to reduce feelings of guilt and loss of control when indulging in cravings. Preoccupation with cravings caused undesirable psychological distress, and this distress was alleviated through acceptance. Overall, women indicated that some degree of tolerance towards their cravings and subsequent eating behaviors facilitated a better mental and emotional status.

Implications

These findings suggest the importance of considering the psychological aspects of food cravings when developing interventions targeting eating behaviors in pregnant women. Accounting for women’s beliefs about the physiological origins of cravings and the psychological effects of resisting or satisfying the cravings may be critical for developing effective message framing and behavioral management strategies. Mindfulness-based eating interventions could help women manage cravings while promoting mental well-being, as this approach addresses emotional aspects of eating and has been effective in promoting healthful eating behaviors in non-pregnant samples42,43.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths and limitations of this study should be considered when evaluating the findings. The sample size is relatively large for focus group studies, and women across the range of BMI were included. However, this was a mostly white, higher income, and higher educated group of women who have access to prenatal care. Furthermore, the women were all part of a larger study assessing eating behaviors, and therefore they may have been more cognizant of dietary intake. The discussion guide was semi-structured, such that some topics were defined a priori, and there is a possibility that some aspects of food cravings during pregnancy were not identified as a result. However, eight focus groups were administered, which should be sufficient for theoretical saturation.

Conclusion

Pregnant women reported food cravings as a common and psychologically salient aspect of their pregnancy. They indicated using a variety of cognitive and behavioral strategies to manage these cravings, including acceptance. An understanding of the emotional precursors and responses to food cravings may assist with the development of interventions to improve eating behaviors and reduce eating-related distress during pregnancy.

Research Snapshot.

Research Question:

How do pregnant women interpret, perceive, experience, and cope with food cravings in pregnancy?

Key Findings:

In this qualitative study using focus groups, 68 pregnant women were recruited from a larger study on eating behaviors and weight gain in pregnancy to share experiences and interpretations of food cravings in pregnancy. Our data suggest that food cravings are psychologically salient aspects of pregnancy, and women’s strategies for coping with them range from behavioral modifications to more cognitively-laden approaches.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Intramural Research Program (contract #HHSN275201300015C and #HHSN275201300026I/HHSN27500002).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Orloff NC, Hormes JM. Pickles and ice cream! Food cravings in pregnancy: hypotheses, preliminary evidence, and directions for future research. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gendall KA, Joyce PR, Sullivan PF. Impact of definition on prevalence of food cravings in a random sample of young women. Appetite. 1997;28(1):63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weingarten HP, Elston D. The phenomenology of food cravings. Appetite. 1990;15(3):231–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orloff NC, Flammer A, Hartnett J, Liquorman S, Samelson R, Hormes JM. Food cravings in pregnancy: Preliminary evidence for a role in excess gestational weight gain. Appetite. 2016;105:259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sotres-Alvarez D, Siega-Riz AM, Herring AH, et al. Maternal dietary patterns are associated with risk of neural tube and congenital heart defects. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(11):1279–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmichael SL, Yang W, Feldkamp ML, et al. Reduced risks of neural tube defects and orofacial clefts with higher diet quality. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(2): 121–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knudsen VK, Orozova-Bekkevold IM, Mikkelsen TB, Wolff S, Olsen SF. Major dietary patterns in pregnancy and fetal growth. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62(4):463–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okubo H, Miyake Y, Sasaki S, et al. Maternal dietary patterns in pregnancy and fetal growth in Japan: the Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. Br J Nutr. 2012;107(10):1526–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson JM, Wall C, Becroft DM, Robinson E, Wild CJ, Mitchell EA. Maternal dietary patterns in pregnancy and the association with small-for-gestational-age infants. Br J Nutr. 2010;103(11):1665–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin CL, Sotres-Alvarez D, Siega-Riz AM. Maternal dietary patterns during the second trimester are associated with preterm birth. J Nutr. 2015;145(8):1857–1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farland LV, Rifas-Shiman SL, Gillman MW. Early pregnancy cravings, dietary intake, and development of abnormal glucose tolerance. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(12):1958–1964 e1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belzer LM, Smulian JC, Lu SE, Tepper BJ. Food cravings and intake of sweet foods in healthy pregnancy and mild gestational diabetes mellitus. A prospective study. Appetite. 2010;55(3):609–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill AJ, Cairnduff V, McCance DR. Nutritional and clinical associations of food cravings in pregnancy. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29(3):281–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renault KM, Carlsen EM, Norgaard K, et al. Intake of sweets, snacks and soft drinks predicts weight gain in obese pregnant women: Detailed analysis of the results of a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tierson FD, Olsen CL, Hook EB. Influence of cravings and aversions on diet in pregnancy. Ecol Food Nutr. 1985;17(2):117–129. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pope JF, Skinner JD, Carruth BR. Cravings and aversions of pregnant adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 1992;92(12):1479–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weigel MM, Coe K, Castro NP, Caiza ME, Tello N, Reyes M. Food aversions and cravings during early pregnancy: association with nausea and vomiting. Ecol Food Nutr. 2011;50(3):197–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodrich K, Cregger M, Wilcox S, Liu J. A qualitative study of factors affecting pregnancy weight gain in African American women. Maternal and child health journal. 2013;17(3):432–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groth SW, Simpson AH, Fernandez ID. The dietary choices of women who are low-income, pregnant, and African American. Journal of midwifery & women’s health. 2016;61(5):606–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Copelton DA. “You are what you eat”: nutritional norms, maternal deviance, and neutralization of women’s prenatal diets. Deviant Behav. 2007;28(5):467–494. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hook EB. Dietary cravings and aversions during pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978;31 (8):1355–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bayley TM, Dye L, Jones S, DeBono M, Hill AJ. Food cravings and aversions during pregnancy: relationships with nausea and vomiting. Appetite. 2002;38(1):45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zellner DA, Garriga-Trillo A, Rohm E, Centeno S, Parker S. Food liking and craving: A cross-cultural approach. Appetite. 1999;33(1):61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osman JL, Sobal J. Chocolate cravings in American and Spanish individuals: biological and cultural influences. Appetite. 2006;47(3):290–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hormes JM, Orloff NC, Timko CA. Chocolate craving and disordered eating. Beyond the gender divide? Appetite. 2014;83:185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hormes JM, Niemiec MA. Does culture create craving? Evidence from the case of menstrual chocolate craving. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bianchi CM, Huneau JF, Le Goff G, Verger EO, Mariotti F, Gurviez P. Concerns, attitudes, beliefs and information seeking practices with respect to nutrition-related issues: a qualitative study in French pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rabiee F Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proc Nutr Soc. 2004;63(4):655–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nansel TR, Lipsky LM, Siega-Riz AM, Burger K, Faith M, Liu A. Pregnancy eating attributes study (PEAS): a cohort study examining behavioral and environmental influences on diet and weight change in pregnancy and postpartum. BMC Nutr. 2016; 2: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coenen M, Stamm TA, Stucki G, Cieza A. Individual interviews and focus groups in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a comparison of two qualitative methods. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(2):359–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guest G, Namey E, McKenna K. How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods. 2016;29(1):3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onwuegbuzie AJ, Dickinson WB, Leech NL, Zoran AG. A aualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in focus group research. 2009;8(3):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. 3rd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Chicago,: Aldine Pub. Co.; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bishaw A, Macartney S. Poverty: 2008 and 2009. US Census Bureu;2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forman EM, Hoffman KL, Juarascio AS, Butryn ML, Herbert JD. Comparison of acceptance-based and standard cognitive-based coping strategies for craving sweets in overweight and obese women. Eating behaviors. 2013;14(1):64–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moffitt R, Brinkworth G, Noakes M, Mohr P. A comparison of cognitive restructuring and cognitive defusion as strategies for resisting a craved food. Psychol Health. 2012;27 Suppl 2:74–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Padmanabhan U, Summerbell CD, Heslehurst N. A qualitative study exploring pregnant women’s weight-related attitudes and beliefs in UK: the BLOOM study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mumford SL, Siega-Riz AM, Herring A, Evenson KR. Dietary restraint and gestational weight gain. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(10):1646–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hill AJ, Weaver CF, Blundell JE. Food craving, dietary restraint and mood. Appetite. 1991;17(3):187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allison DB, Heshka S. Emotion and eating in obesity? A critical analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 1993;13(3):289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blau LE, Orloff NC, Flammer A, Slatch C, Hormes JM. Food craving frequency mediates the relationship between emotional eating and excess weight gain in pregnancy. Eating behaviors. 2018;31:120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jordan CH, Wang W, Donatoni L, Meier BP. Mindful eating: Trait and state mindfulness predict healthier eating behavior. Pers Individ Dif. 2014;68:107–111. [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Reilly GA, Cook L, Spruijt-Metz D, Black DS. Mindfulness-based interventions for obesity-related eating behaviours: a literature review. Obes Rev. 2014;15(6):453–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Webb JB, Siega-Riz AM, Dole N. Psychosocial determinants of adequacy of gestational weight gain. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2009;17(2):300–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mehta UJ, Siega-Riz AM, Herring AH. Effect of body image on pregnancy weight gain. Maternal and child health journal. 2011;15(3):324–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hill B, Skouteris H, McCabe M, et al. A conceptual model of psychosocial risk and protective factors for excessive gestational weight gain. Midwifery. 2013;29(2):110–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]